Network effect

A network effect (also called network externality or demand-side economies of scale) is the effect described in economics and business that an additional user of goods or services has on the value of that product to others. When a network effect is present, the value of a product or service increases according to the number of others using it.[1]

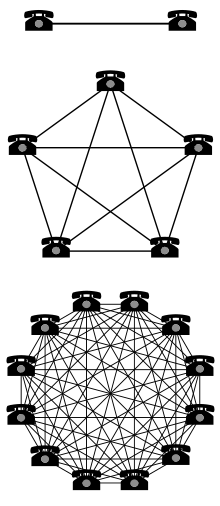

The classic example is the telephone, where a greater number of users increases the value to each. A positive externality is created when a telephone is purchased without its owner intending to create value for other users, but does so regardless. Online social networks work similarly, with sites like Twitter and Facebook increasing in value to each member as more users join.

The network effect can create a bandwagon effect as the network becomes more valuable and more people join, resulting in a positive feedback loop.

The expression "network effect" is applied to positive network externalities as in the case of the telephone. Negative network externalities can also occur, where more users make a product less valuable, but they are more commonly referred to as "congestion" (as in traffic congestion or network congestion).

Origins

Network effects were a central theme in the arguments of Theodore Vail, the first post-patent president of Bell Telephone, in gaining a monopoly on US telephone services. In 1908, when he presented the concept in Bell's annual report, there were over 4,000 local and regional telephone exchanges, most of which were eventually merged into the Bell System.

Network effects were popularized by Robert Metcalfe, stated as Metcalfe's law. Metcalfe was one of the co-inventors of Ethernet and a co-founder of the company 3Com. In selling the product, Metcalfe argued that customers needed Ethernet cards to grow above a certain critical mass if they were to reap the benefits of their network.[2] According to Metcalfe, the rationale behind the sale of networking cards was that the cost of the network was directly proportional to the number of cards installed, but the value of the network was proportional to the square of the number of users. This was expressed algebraically as having a cost of N, and a value of N2. While the actual numbers behind this proposition were never firm, the concept allowed customers to share access to expensive resources like disk drives and printers, send e-mail, and eventually access the Internet.

The economic theory of the network effect was advanced significantly between 1985 and 1995 by researchers Michael L. Katz, Carl Shapiro, Joseph Farrell and Garth Saloner.[3] Author, high-tech entrepreneur Rod Beckstrom presented a mathematical model for describing networks that are in a state of positive network effect at BlackHat and Defcon in 2009 and also presented the "inverse network effect" with an economic model for defining it as well.[4]

Benefits

Network effects become significant after a certain subscription percentage has been achieved, called critical mass. At the critical mass point, the value obtained from the good or service is greater than or equal to the price paid for the good or service. As the value of the good is determined by the user base, this implies that after a certain number of people have subscribed to the service or purchased the good, additional people will subscribe to the service or purchase the good due to the value exceeding the price.

A key business concern must then be how to attract users prior to reaching critical mass. One way is to rely on extrinsic motivation, such as a payment, a fee waiver, or a request for friends to sign up. A more natural strategy is to build a system that has enough value without network effects, at least to early adopters. Then, as the number of users increases, the system becomes even more valuable and is able to attract a wider user base.

Beyond critical mass, the increasing number of subscribers generally cannot continue indefinitely. After a certain point, most networks become either congested or saturated, stopping future uptake. Congestion occurs due to overuse. The applicable analogy is that of a telephone network. While the number of users is below the congestion point, each additional user adds additional value to every other customer. However, at some point, the addition of an extra user exceeds the capacity of the existing system. After this point, each additional user decreases the value obtained by every other user. In practical terms, each additional user increases the total system load, leading to busy signals, the inability to get a dial tone, and poor customer support. Assuming the congestion point is below the potential market size, the next critical point is where the value obtained again equals the price paid. The network will cease to grow at this point if system capacity is not improved. Peer-to-peer (P2P) systems are networks designed to distribute load among their user pool. This theoretically allows P2P networks to scale indefinitely. The P2P based telephony service Skype benefits from this effect and its growth is limited primarily by market saturation.

Network effects are commonly mistaken for economies of scale, which result from business size rather than interoperability. To help clarify the distinction, people speak of demand side vs. supply side economies of scale. Classical economies of scale are on the production side, while network effects arise on the demand side. Network effects are also mistaken for economies of scope. Because of the positive feedback often associated with the network effect, system dynamics can be used as a modelling method to describe the phenomena. Word of mouth and the Bass diffusion model are also potentially applicable.

Technology lifecycle

If some existing technology or company whose benefits are largely based on network effects starts to lose market share against a challenger such as a disruptive technology or open standards based competition, the benefits of network effects will reduce for the incumbent, and increase for the challenger. In this model, a tipping point is eventually reached at which the network effects of the challenger dominate those of the former incumbent, and the incumbent is forced into an accelerating decline, whilst the challenger takes over the incumbent's former position.

Lock-in

Network effects are notorious for causing lock-in with the most-cited examples being Microsoft products and the QWERTY keyboard.[5] Vendor lock-in can be mitigated by opening the standards upon which users depend, allowing competition between implementations. This does not, however, mitigate industry-wide lock-in to the standard itself. Indeed, as there are now multiple vendors driving down the price and increasing the quality, more users are likely to adopt the standard, thereby creating greater industry-wide lock-in to the standard.

Types

Broadly, there are two kinds of networks effects:

- Direct network effects

- An increase in usage leads to a direct increase in value for other users. For example, telephone systems, fax machines, and social networks all imply direct contact among users. A direct network effect is called a same-side network effect. An example is online gamers who benefit from participation of other gamers.

- Indirect network effects

- Increases in usage of one product or network spawn increases in the value of a complementary product or network, which can, in turn, increase the value of the original. Examples of complementary goods include software (such as an Office suite for operating systems) and DVDs (for DVD players). This is also called a cross-side network effect. Windows and Linux might compete not just for users, but for software developers.[6] Most two-sided markets (or platform-mediated markets) are characterized by indirect network effects.

Additionally, there are two sources of economic value that are relevant when analyzing products that display network effects:

- Inherent value

- I derive value from my use of the product

- Network value

- I derive value from other people's use of the product

Negative network externalities

Negative network externalities, in the mathematical sense, are those that have a negative effect compared to normal (positive) network effects. Just as positive network externalities (network effects) cause positive feedback and exponential growth, negative network externalities create negative feedback and exponential decay. In nature, negative network externalities are the forces that pull towards equilibrium, are responsible for stability, and represent physical limitations keeping systems bounded.

Congestion occurs when the efficiency of a network decreases as more people use it, and this reduces the value to people already using it. Traffic congestion that overloads the freeway and network congestion on connections with limited bandwidth both display negative network externalities.

Braess' paradox suggests that adding paths through a network can have a negative effect on performance of the network.[7]

Interoperability

Interoperability has the effect of making the network bigger and thus increases the external value of the network to consumers. Interoperability achieves this primarily by increasing potential connections and secondarily by attracting new participants to the network. Other benefits of interoperability include reduced uncertainty, reduced lock-in, commoditization and competition based on price.[1]:229

Interoperability can be achieved through standardization or other cooperation. Companies involved in fostering interoperability face a tension between cooperating with their competitors to grow the potential market for products and competing for market share.[1]:227

Open versus closed standards

In communication and information technologies, open standards and interfaces are often developed through the participation of multiple companies and are usually perceived to provide mutual benefit. But, in cases in which the relevant communication protocols or interfaces are closed standards, the network effect can give the company controlling those standards monopoly power. The Microsoft corporation is widely seen by computer professionals as maintaining its monopoly through these means. One observed method Microsoft uses to put the network effect to its advantage is called Embrace, extend and extinguish.[8]

Mirabilis is an Israeli start-up which pioneered instant messaging (IM) and was bought by America Online. By giving away their ICQ product for free and preventing interoperability between their client software and other products, they were able to temporarily dominate the market for instant messaging. Because of the network effect, new IM users gained much more value by choosing to use the Mirabilis system (and join its large network of users) than they would using a competing system. As was typical for that era, the company never made any attempt to generate profits from its dominant position before selling the company.

Examples

Financial exchanges

Stock exchanges and derivatives exchanges feature a network effect. Market liquidity is a major determinant of transaction cost in the sale or purchase of a security, as a bid–ask spread exists between the price at which a purchase can be made versus the price at which the sale of the same security can be made. As the number of buyers and sellers on an exchange increases, liquidity increases, and transaction costs decrease. This then attracts a larger number of buyers and sellers to the exchange.

The network advantage of financial exchanges is apparent in the difficulty that startup exchanges have in dislodging a dominant exchange. For example, the Chicago Board of Trade has retained overwhelming dominance of trading in US Treasury bond futures despite the startup of Eurex US trading of identical futures contracts. Similarly, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange has maintained dominance in trading of Eurobond interest rate futures despite a challenge from Euronext.Liffe.

Software

There are very strong network effects operating in the market for widely used computer software.

For many people choosing an office suite, prime considerations include how much value having learned that office suite will prove to potential employers, and how well the software interoperates with other users. That is, since learning to use an office suite takes many hours, users want to invest that time learning the office suite that will make them most attractive to potential employers and clients. Similarly, finding already-trained employees is a big concern for employers when deciding which office suite to purchase.

In 2007 Apple released the iPhone followed by the app store. Most iPhone apps rely heavily on the existence of strong network effects. This enables the software to grow in popularity very quickly and spread to a large userbase with very limited marketing needed. The Freemium business model has evolved to take advantage of these network effects by releasing a free version that will not limit the adoption or any users and then charge for premium features as the primary source of revenue.

Web sites

Many web sites benefit from a network effect. One example is web marketplaces and exchanges. For example, eBay would not be a particularly useful site if auctions were not competitive. However, as the number of users grows on eBay, auctions grow more competitive, pushing up the prices of bids on items. This makes it more worthwhile to sell on eBay and brings more sellers onto eBay, which drives prices down again as this increases supply while bringing more people onto eBay because there are more things being sold that people want. Essentially, as the number of users of eBay grows, prices fall and supply increases, and more and more people find the site to be useful.

Network effects were used as justification for some of the dot-com business models in the late 1990s. These firms operated under the belief that when a new market comes into being which contains strong network effects, firms should care more about growing their market share than about becoming profitable. This was believed because market share will determine which firm can set technical and marketing standards and thus determine the basis of future competition.

Social networking websites are good examples. The more people register onto a social networking website, the more useful the website is to its registrants.[9]

Alexa Internet uses a technology that tracks users' surfing patterns; thus Alexa's Related Sites results improve as more users use the technology. Alexa's network relies heavily on a small number of browser software relationships, which makes the network more vulnerable to competition.

Google has also attempted to create a network effect in its advertising business with its Google AdSense service. Google AdSense places ads on many small sites, such as blogs, using Google technology to determine which ads are relevant to which blogs. Thus, the service appears to aim to serve as an exchange (or ad network) for matching many advertisers with many small sites (such as blogs). In general, the more blogs Google AdSense can reach, the more advertisers it will attract, making it the most attractive option for more blogs, and so on, making the network more valuable for all participants.

By contrast, the value of a news site is primarily proportional to the quality of the articles, not to the number of other people using the site. Similarly, the first generation of search sites experienced little network effect, as the value of the site was based on the value of the search results. This allowed Google to win users away from Yahoo! without much trouble, once users believed that Google's search results were superior. Some commentators mistook the value of the Yahoo! brand (which does increase as more people know of it) for a network effect protecting its advertising business.

Rail gauge

There are strong network effects in the initial choice of rail gauge, and in gauge conversion decisions. Even when placing isolated rails not connected to any other lines, track layers usually choose a standard rail gauge so they can use off-the-shelf rolling stock. Although a few manufacturers make rolling stock that can adjust to different rail gauges, most manufacturers make rolling stock that only works with one of the standard rail gauges.

See also

- Anti-rival good

- Beckstrom's law

- Betamax

- Cluster effect

- Economies of density

- First-mover advantage

- Market failure

- Metcalfe's law

- Monopoly

- Monopsony

- Oligopoly

- Open format

- Open system (computing)

- Path dependence

- Reed's law

- Returns to scale (increasing returns)

- Semantic Web

- Two-sided market

- Unfair competition

References

- Carl Shapiro and Hal R. Varian (1999). Information Rules. Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 0-87584-863-X.

- "It's All In Your Head". Forbes. 2007-05-07. Retrieved 2010-12-10.

- Knut Blind (2004). The economics of standards: theory, evidence, policy. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84376-793-0.

- Buley, Taylor (2009-07-31). "How To Value Your Networks". Forbes. Retrieved 2010-12-10.

- Robert M. Grant (2009). Contemporary Strategy Analysis. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-74710-0.

- Nicholas Economides and Evangelos Katsamakas (May 2008). "Two-sided competition of proprietary vs. open source technology platforms and the implications for the software industry" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-19. Retrieved 2010-12-10.

- Lin, Henry; Roughgarden, Tim; Tardos, Éva; Walkover, Asher. "Stronger Bounds on Braess's Paradox and the Maximum Latency of Selfish Routing" (PDF). Stanford Theory. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- "US Department of Justice Proposed Findings of Fact". Usdoj.gov. Retrieved 2016-04-28.

- Belvaux, Bertrand (2011). "The Development of Social Media: Proposal for a Diffusion Model Incorporating Network Externalities in a Competitive Environment". Recherche et Applications en Marketing - English Version. 26 (3): 7–22. doi:10.1177/205157071102600301.

External links

- Coordination and Lock-In: Competition with Switching Costs and Network Effects, Joseph Farrell and Paul Klemperer.

- Network Externalities (Effects), S. J. Liebowitz, Stephen E. Margolis.

- An Overview of Network Effects, Arun Sundararajan.

- The Economics of Networks, Nicholas Economides.

- Madureira, António; den Hartog, Frank; Bouwman, Harry; Baken, Nico (2013). "Empirical validation of Metcalfe's law: How Internet usage patterns have changed over time". Information Economics and Policy. 25 (4): 246–256. doi:10.1016/j.infoecopol.2013.07.002.