Allonsanfàn

Allonsanfàn (Italian pronunciation: [ˌallɔŋˈsanˈfaŋ]) is a 1974 Italian historical drama film written and directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, with a score composed by Ennio Morricone.

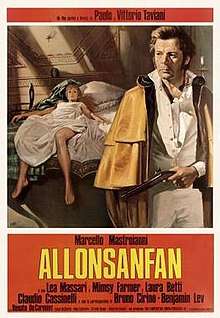

| Allonsanfàn | |

|---|---|

Italian theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Paolo Taviani Vittorio Taviani |

| Produced by | Giuliani G. De Negri |

| Written by | Paolo Taviani Vittorio Taviani |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Ennio Morricone |

| Cinematography | Giuseppe Ruzzolini |

| Edited by | Roberto Perpignani |

Production company | Una Cooperativa Cinematografica |

| Distributed by | Italnoleggio Cinematografico |

Release date |

|

Running time | 111 minutes |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

| Box office | L.415 million[1] |

Set against the backdrop of the Restoration in early 19th-century Italy, the film stars Marcello Mastroianni as a disillusioned revolutionary that tries to betray his comrades, which are organizing a revolution in the South. The title of the film, which is also the name of a character, refers to the first words (French: Allons enfants, lit. 'Arise, children') of La Marseillaise.[2][3][4]

Plot

In 1816, middle-aged aristocrat Fulvio Imbriani, a Jacobin who served in the Italian campaigns of the French Revolutionary Wars, is released from the Austrian prison he was incarcerated in after the Restoration. Authorities hope that he'll lead them to the secret revolutionary society he belongs to, the Sublime Brothers, having spread the news that he sold out its Master. Promptly kidnapped by his bumbling comrades, Fulvio is put on trial until they find out that their missing Master hanged himself days earlier, disheartened by the seemingly-final defeat of revolutionary ideals. The dismayed Brothers soon break up, with Fulvio returning to his family villa, parting ways with best friend and comrade Tito.

Here, Fulvio initially disguises himself as a priest friend of his, but after witnessing the family mourn his ostensible death, he reveals himself and is welcomed back. After a while, he's joined by his Hungarian lover and fellow revolutionary Charlotte, learning that she raised enough funds in Great Britain to finance a revolutionary expedition in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, currently ravaged by a cholera epidemic. Fulvio, however, has grown weary of his seemingly unending and unfruitful purpose, revaluating the eases of aristocratic life. He unsuccessfully offers Charlotte to flee to America with their little son Massimiliano, who has been raised by peasants to keep him safe. Fulvio's sister learns that the reunited Brothers will come to the villa to organize the expedition and secretly reports them to the authorities. Fulvio finds out that Austrian soldiers are about to ambush his comrades and sees the opportunity to get rid of them by doing nothing: in the ensuing skirmish, most Brothers are killed and Fulvio escapes with a mortally wounded Charlotte.

At her funeral, he's joined again by Tito and the surviving Brothers, oblivious to his betrayal and now followed by the Master's young son, Allonsanfàn. After learning that the expedition is still on, Fulvio offers to buy himself the weapons with Charlotte's money, with which he actually plans to escape to America, along with a newly reunited Massimiliano, but he's tailed by Brother Lionello and his partner Francesca. To get rid of them, he goes boating with the former in Lake Orta, where he claims smugglers will deliver the weapons. Fulvio then pretends to having been ripped off and tries to manipulate Lionello into killing himself to avoid facing failure, aware of his suicidal tendencies; Lionello doesn't find the determination needed but dies anyway when the boat capsizes during an argument. Fulvio is rescued by a group of libertines passing through and, to avoid being denounced to the Brothers, seduces and gaslights Francesca. After placing Massimiliano in a boarding school and using the money to pay the rent in the event of his death, he self-injures to simulate a robbery.

In Genoa, where the expedition should set off, the Brothers are moved by Southern exile Vanni Gavina, telling them how Bourbon soldiers buried alive his wife due to cholera, to the point where they leave for Sicily before the lack of weapons could be revealed: while Fulvio is unconscious from an opium medicine for his injury, Francesca has him boarded with the other comrades. After learning about the missing weapons, the Brothers unanimously choose to continue the expedition anyway, while an increasingly desperate Fulvio finds out that Vanni is an infamous criminal in the South for exacting revenge for his wife on many soldiers and fellow countrymen. As soon as they land, he once again betrays his comrades, reporting them to a priest in the nearby village of Grottole in exchange for his life. Fearing that the poor and cholera-stricken peasants would easily join the rebellion, the priest stirs up them against the revolutionaries, scapegoating them for the epidemic and highlighting the presence of Vanni. Easily recognizable because of their red shirts, the oblivious Brothers are lynched on the spot by the crowd.

Unaware of what happened, Fulvio is fleeing Grottole when he's joined by Allonsanfàn, the sole survivor of the massacre. Suffering from a head injury and unable to accept the outcome of the expedition, he raves about a utopian brotherhood established at first sight between peasants and revolutionaries, visualizing them dancing together the Southern folk dance Vanni taught them. Fulvio scoffs at him, but after hearing the town's bells ringing, he believes that his comrades succeeded and leaves to join them, wearing Allonsanfàn's red shirt. In this way, he's noticed and shot dead by newly arrived soldiers.

Cast

- Marcello Mastroianni as Fulvio Imbriani

- Lea Massari as Charlotte

- Mimsy Farmer as Francesca

- Laura Betti as Esther Imbriani

- Claudio Cassinelli as Lionello

- Benjamin Lev as Vanni 'Peste' Gavina

- Renato De Carmine as Costantino Imbriani

- Stanko Molnar as Allonsanfàn

- Luisa De Santis as Fiorella Imbriani

- Biagio Pelligra as Grottole's Priest

- Michael Berger as Remigio Imbriani

- Raul Cabrera as Sublime Brother

- Alderice Casali as Concetta

- Roberto Frau as Sublime Brother[1]

- Cirylle Spiga as Massimo

- Ermanno Taviani as Massimiliano Imbriani

- Francesca Taviani as Giovanna

- Bruno Cirino as Tito

Production

The events of the film mirror the ill-fated 1857 revolutionary expedition led by Carlo Pisacane, while the surname of the main character is an homage to the Italian author of the period Vittorio Imbriani.[3] Following the success of St. Michael Had a Rooster (1972), the film was produced by a cooperative financed by the State-owned company Italnoleggio Cinematografico.[5][6]

The Taviani brothers wrote the screenplay for the film, originally titled Terza dimensione (lit. 'Third Dimension'), while listening to 19th-century Italian operas such as Lucia di Lammermoor by Gaetano Donizetti and Giuseppe Verdi's Macbeth.[5] Mastroianni chose the role of Fulvio since he perceived it as "the typical antihero character I like to play".[4]

Filming

Principal photography took place between October and December 1973.[4][7][8] Among the locations were Matera, Basilicata, and the Altopiano delle Murge in Apulia, at Pulo di Altamura and Castel del Monte.[9][10] Scenes set at the Imbriani's family villa were shot at Villa Amalia in Erba, Lombardy.[4] Both the opening scene and the violin scene between Fulvio and his son were shot in Brescia, at the Broletto and Teatro Grande.[11] The scene where the Sublime Brothers kidnap Fulvio was shot in Bergamo, between Piazza Vecchia and Palazzo della Ragione.[12]

Singer and songwriter Lucio Dalla was set to play Tito and some scenes were shot with him in the role, but was hospitalized during filming and had to be replaced by Bruno Cirino.[13]

Soundtrack

The score was composed by Ennio Morricone and directed by Bruno Nicolai, with chorus by Alessandro Alessandroni's I Cantori Moderni and solo violin by Giorgio Mönch.[1][14][15] Tavianis' previous composer Giovanni Fusco introduced Morricone to the directors, who originally didn't want to use any original music for the film.[5] A soundtrack album was released in Italy by RCA Italiana.[1]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Rabbia e tarantella" | 3:53 |

| 2. | "Ritorno a casa" | 2:56 |

| 3. | "Dirindindin" | 2:12 |

| 4. | "Frammenti di sonata" | 3:04 |

| 5. | "Tradimento" | 2:36 |

| 6. | "Te Deum laudamus" | 6:48 |

| 7. | "Allonsanfàn (Sul lago)" | 1:38 |

| 8. | "Allonsanfàn (Ballata)" | 1:40 |

| 9. | "Rabbia e tarantella (2)" | 1:06 |

| 10. | "Te Deum laudamus (2)" | 2:11 |

| 11. | "Allonsanfàn (Fantasmi)" | 2:12 |

| 12. | "Dirindindin (2)" | 0:58 |

| 13. | "Frammenti di sonata (2)" | 1:47 |

| 14. | "Ritorno a casa (2)" | 1:06 |

| 15. | "Rabbia e tarantella (3)" | 2:58 |

"Rabbia e tarantella", the main theme of the film, was used during the closing credits of Quentin Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds (2009).[16]

Release

Allonsanfàn premiered at the Cinema Arcadia in Milan on 5 September 1974,[6] before being theatrically released the following day by Italnoleggio Cinematografico.[5] It was subsequently screened at various international film festivals, including the Directors' Fortnight of the 1975 Cannes Film Festival,[17] the Moscow International Film Festival,[18] the BFI London Film Festival and the Chicago International Film Festival.[16]

It was released in the United States by Italtoons Corporation on 1 March 1985.[2]

Accolades

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicago International Film Festival | 1975 | Gold Hugo | Allonsanfàn | Nominated | |

| Grolla d'Oro Awards | 4 July 1975 | Best Director | Paolo and Vittorio Taviani | Nominated | [19][20] |

| Best Actor | Marcello Mastroianni | Nominated | |||

| Nastro d'Argento Awards | 1975 | Best Actress | Lea Massari | Nominated | |

| Best Original Story | Paolo and Vittorio Taviani | Nominated |

References

- Poppi, Roberto; Pecorari, Mario (1991). Dizionario del cinema italiano: I film. Vol. 4/1: Dal 1970 al 1979. A-L (in Italian). Rome: Gremese Editore. p. 33. ISBN 8876059350.

- Janet Maslin (1 March 1985). "Screen: Early Taviani". The New York Times. p. 12. Retrieved 2009-03-28.

- Crespi, Alberto (2016). Storia di Italia in 15 film (in Italian) (3 ed.). Bari: Laterza. ISBN 978-8858125229. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Tornabuoni, Lietta (17 October 1973). "Mastroianni il traditore" [Mastroianni the traitor]. La Stampa (in Italian) (244). p. 3. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- De Santi, Pier Marco (1988). I film di Paolo e Vittorio Taviani (in Italian). Rome: Gremese Editore. pp. 87–88. ISBN 9788876053115.

- Valdata, Achille (5 September 1975). "Allonsanfàn, su invito" [Allonsanfàn, on invitation]. Stampa Sera (in Italian) (106). p. 8. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Roma. Lea Massari è la donna di Mastroianni in "Allonsanfan" che i fratelli Taviani termineranno tra poco" [Rome. Lea Massari is Mastroianni's girl in «Allonsanfan», which the Taviani brothers will soon complete]. Stampa Sera (in Italian) (271). 20 November 1973. p. 9. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Rivale di Lea Massari" [A foe to Lea Massari]. La Stampa (in Italian) (288). 7 December 1973. p. 22. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Film girati a Matera" [Films shot in Matera]. Sassiweb.it (in Italian). Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Attolini, Vito. "Allonsanfàn". Apulia Film Commission. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Dolfo, Nino (11 April 2012). "Quando la Leonessa ruggisce al cinema" [When the Lioness roars, at the movies]. Corriere della sera. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Tabani, Maurizio (16 April 2018). "Tabani: "Io figurante in Allonsanfan dei Taviani, girato in Città Alta"" [Tabani: “I, extra in Tavianis' Allonsanfan, filmed in the high part of the city”]. bergamonews.it. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "Il maestro Cirino sostituisce Dalla" [Maestro Cirino to replace Dalla]. Stampa Sera (in Italian) (249). 25 October 1973. p. 6. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Ennio Morricone – Allonsanfan (Colonna Sonora Originale) at Discogs

- Messina, Levia Agostina. "Allonsanfan". colonnesonore.net (in Italian). Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "Lost and found: Allonsanfàn". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 2012-08-03. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

- "Quinzaine 1975". quinzaine-realisateurs.com (in French). Cannes Film Festival. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- "Film italiani al Festival di Mosca" [Italian films at the Moscow Film Festival]. Stampa Sera (in Italian) (146). 7 July 1975. p. 6. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Gassman e gli altri soliti noti candidati alle "Grolle d'oro 75"" [Gassman and the usual bunch nominated at the 1975 Grollas]. Stampa Sera (in Italian) (129). 16 June 1975. p. 6. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- r.s. (5 July 1975). "Le grolle d'oro, senza il "gala" a Gassman e Stefania Sandrelli" [Grolla d'oro awards without the "gala" for Gassman and Stefania Sandrelli]. La Stampa (in Italian) (152). p. 7. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Allonsanfàn. |

- Allonsanfàn on IMDb

- Allonsanfàn at AllMovie