John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry

John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry (also spelled Harper's Ferry)[2] was an effort by abolitionist John Brown, from October 16 to 18, 1859, to initiate a slave revolt in Southern states by taking over a United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. It has been called the dress rehearsal for the Civil War.[3]:5

| John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Origins of the American Civil War | |||||||

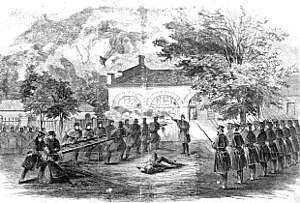

Harper's Weekly illustration of U.S. Marines attacking John Brown's "Fort" | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Abolitionist insurgents | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

John Brown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

U.S. Marines:

|

| ||||||

Civilians:

| |||||||

Location within West Virginia | |||||||

Brown's party of 22[1] was defeated by a company of U.S. Marines, led by First Lieutenant Israel Greene.[4] Several of those present at the raid would later be involved in the Civil War: Colonel Robert E. Lee was in overall command of the operation to retake the arsenal. Stonewall Jackson and Jeb Stuart were part of the troops guarding the arrested Brown,[3]:5 and John Wilkes Booth was a spectator at his execution. John Brown had originally asked Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, both of whom he had met in his transformative years as an abolitionist in Springfield, Massachusetts, to join him in his raid, but Tubman was prevented by illness and Douglass declined, as he believed Brown's plan would fail.[5]

The label "raid" was not used at the time. A month after the attack, a Baltimore newspaper listed 26 terms used, including "insurrection", "rebellion", "treason", and "crusade". "Raid" was not among them.[3]:4

Brown's preparation

John Brown rented the Kennedy Farmhouse, with a small cabin nearby, 4 miles (6.4 km) north of Harpers Ferry near the community of Dargan in Washington County, Maryland,[6] and took up residence under the name Isaac Smith. Brown came with a small group of men minimally trained for military action. His group included 18 men besides himself (13 white men, 5 black men). Northern abolitionist groups sent 198 breech-loading .52 caliber Sharps carbines ("Beecher's Bibles") and 950 pikes (obtained in late September from Charles Blair of Collinsville Axe Company in Collinsville, Connecticut), in preparation for the raid. The United States Armory was a huge complex of buildings that manufactured small arms for the U.S. Army (1801–1861), with an Arsenal (storehouse) that was thought to contain 100,000 muskets and rifles at the time.[7]

Brown attempted to attract more black recruits. He tried recruiting Frederick Douglass as a liaison officer to the slaves in a meeting held in a quarry at Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. It was at this meeting that ex-slave "Emperor" Shields Green consented to join with John Brown on his attack on the United States Armory, Green stating to Douglass "I believe I will go with the old man". Douglass declined, indicating to Brown that he believed the raid was a suicide mission. The plan was "an attack on the federal government" that "would array the whole country against us ... You will never get out alive", he warned.[8]

The Kennedy Farmhouse served as "barracks, arsenal, supply depot, mess hall, debate club, and home". It was very crowded and life there was tedious. Brown was worried about arousing neighbors' suspicions. As a result, the raiders had to stay indoors during the daytime, without much to do but study, drill, argue politics, discuss religion, and play cards and checkers. Brown's daughter-in-law Martha served as cook and housekeeper. His daughter Annie served as lookout. Brown wanted women at the farm, to prevent suspicions of a large all-male group. The raiders went outside at night to drill and get fresh air. Thunderstorms were welcome since they concealed noise from Brown's neighbors.[9]

Brown did not plan to have a sudden raid and escape to the mountains. Rather, he intended to use those rifles and pikes he captured at the arsenal, in addition to those he brought along, to arm rebellious slaves with the aim of striking terror in the slaveholders in Virginia. He believed that on the first night of action, 200–500 black slaves would join his line. He ridiculed the militia and regular army that might oppose him. He planned to send agents to nearby plantations, rallying the slaves. He planned to hold Harpers Ferry for a short time, expecting that as many volunteers, white and black, would join him as would form against him. He would move rapidly southward, sending out armed bands along the way. They would free more slaves, obtain food, horses and hostages, and destroy slaveholders' morale. Brown planned to follow the Appalachian Mountains south into Tennessee and even Alabama, the heart of the South, making forays into the plains on either side.[10]

Advance knowledge of the raid

Brown paid Hugh Forbes $600 (equivalent to $16,464 in 2019) to be his drillmaster. Forbes was an English mercenary who served Giuseppe Garibaldi in Italy. Forbes' Manual for the Patriotic Volunteer was found in Brown's papers after the raid. Brown and Forbes argued over strategy and money. Forbes wanted more money so that his family in Europe could join him.[11] Forbes sent threatening letters to Brown's backers in an attempt to get money. Failing in this effort, Forbes traveled to Washington, DC, and met with U.S. Senators William H. Seward and Henry Wilson. He denounced Brown to Seward as a "vicious man" who needed to be restrained, but did not disclose any plans for the raid. Forbes partially exposed the plan to Senator Wilson and others. Wilson wrote to Samuel Gridley Howe, a Brown backer, advising him to get Brown's backers to retrieve the weapons intended for use in Kansas. Brown's backers told him that the weapons should not be used "for other purposes, as rumor says they may be".[12]:248 In response to warnings, Brown had to return to Kansas to shore up support and discredit Forbes. Some historians believe that this trip cost Brown valuable time and momentum.[13]

Estimates are that at least eighty people knew about Brown's planned raid in advance. Many others had reasons to believe that Brown was contemplating a move against the South. One of those who knew was David J. Gue of Springdale, Iowa. Gue was a Quaker who believed that Brown and his men would be killed. Gue, his brother, and another man decided to warn the government "to protect Brown from the consequences of his own rashness". Gue sent an anonymous letter dated August 20, 1859, to Secretary of War John B. Floyd. The letter said that "old John Brown, late of Kansas," was planning to organize a slave uprising in the South. It said that Brown had a secret agent "in an armory" in Maryland, and that he was stockpiling weapons at a secret location in Maryland. Gue warned that Brown planned to leave Maryland and enter Virginia at Harpers Ferry. Gue acknowledged that he was afraid to disclose his identity but asked Floyd not to ignore his warning "on that account". He was hoping that Floyd would send soldiers to Harpers Ferry. He hoped that the extra security would motivate Brown to call off his plans.[12]:284–285

Even though President Buchanan offered a $250 reward for Brown, Floyd did not connect the John Brown of Gue's letter to the John Brown of Pottawatomie, Kansas, fame. He knew that Maryland did not have an armory (Harpers Ferry is just across the river from Maryland). Floyd concluded that the letter writer was a crackpot, and disregarded it. He later said that "a scheme of such wickedness and outrage could not be entertained by any citizen of the United States".[12]:285

Timeline of the raid

October 16

| North American slave revolts |

|---|

Toussaint Louverture |

|

On Sunday night, October 16, 1859, Brown left four of his men behind as a rear-guard: his son, Owen Brown, Barclay Coppock, Frank Meriam, and one other; he led the rest into the town of Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown detached a party under John Cook Jr. to capture Colonel Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of George Washington, at his nearby Beall-Air estate, free some of his slaves, and seize two relics of George Washington: a sword allegedly presented to Washington by Frederick the Great and two pistols given by Marquis de Lafayette, which Brown considered talismans.[14] The party carried out its mission and returned via the Allstadt House, where they took more hostages.[15] Brown's main party captured several watchmen and townspeople in Harpers Ferry.

Brown's men needed to capture the weapons and escape before word could be sent to Washington. The raid was going well for Brown's men. They cut the telegraph wire and seized a Baltimore & Ohio train passing through towards Washington. For some reason, Brown let the train continue, and at the next station the conductor sent a telegram to B&O headquarters in Baltimore, who telegraphed President Buchanan.

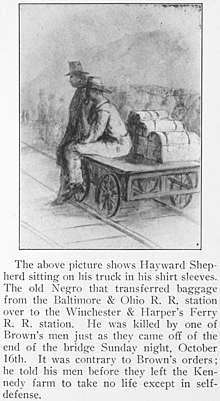

A free black man was the first casualty of the raid: Heyward Shepherd, a baggage handler at the Harpers Ferry train station. He was shot from behind when he by chance encountered the first of the raiders, refused to freeze, and headed back to the station.[16] (See Heyward Shepherd monument.) That a black man was the first casualty of an insurrection whose purpose was to aid blacks, and that he disobeyed the raiders, made him a hero of the "Lost Cause" pro-Confederacy movement.

Brown had been sure that he would get major support from slaves ready to rebel. He "drew considerable support from enslaved African Americans around Harpers Ferry, ... including some who came from plantations that the raiders never visited".[17]:252 The number was not high; one source says "about 30".[17]:175 It was not enough to make a difference. Enslaved men, the degree of whose enthusiasm for Brown's project is unknown, usually knew nothing about firearms.

Although the white townspeople soon began to fight back against the raiders, Brown's men succeeded in capturing the federal armory.

October 17

Army workers discovered Brown's men early on the morning of October 17. Local militia, farmers and shopkeepers surrounded the armory. When a company of militia captured the bridge across the Potomac River, any route of escape for the raiders was cut off. During the day, four townspeople were killed, including the mayor. Realizing his escape was cut, Brown took nine of his captives and moved into the smaller engine home, which would come to be known as John Brown's Fort. The raiders blocked entry of the windows and doors and traded sporadic gunfire with surrounding forces. At one point Brown sent out his son, Watson, and Aaron Dwight Stevens with a white flag, but Watson was mortally wounded and Stevens was shot and captured. The raid was rapidly failing. One of Brown's men, William H. Leeman, panicked and made an attempt to flee by swimming across the Potomac River, but he was shot and fatally injured while doing so. During the intermittent shooting, Brown's other son, Oliver, was also hit; he died after a brief period.[18]

At around 3:00 p.m. a militia company led by Captain E. G. Alburtis arrived by train from Martinsburg, Virginia. Most of the militia members were Baltimore & Ohio Railroad employees. The militia forced the raiders inside the engine house. They broke into the guardroom and freed over two dozen prisoners. Eight militiamen were wounded. Alburtis said that he could have ended the raid with help from other citizens.[19]

By 3:30 that afternoon, President James Buchanan ordered a company of U.S. Marines (the only government troops in the immediate area) to march on Harpers Ferry under the command of Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee, lieutenant colonel of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry Regiment. Lee had been on leave from his regiment, stationed in Texas, when he was hastily called to lead the detachment and had to command it while wearing his civilian clothes.[20]

October 18

The Marines arrived in Harpers Ferry by train in the early morning hours before dawn. Lee first offered the role of attacking the engine house to the local militia units on the spot. Both militia commanders declined, and Lee turned to the Marines. On the morning of October 18, Colonel Lee sent Lt. J. E. B. Stuart, serving as a volunteer aide-de-camp, under a white flag of truce to negotiate a surrender of John Brown and his followers. Colonel Lee informed Lt. Israel Greene that if Brown did not surrender, he was to direct the Marines in attacking the engine house. Stuart walked towards the front of the engine house where he told Brown that his men would be spared if they surrendered. Brown refused and as Stuart walked away, he signaled a "thumbs down" to Lt. Greene and his men standing nearby.

Soon after, Greene led a detachment of Marines to attack the engine house with fixed bayonets. Marines equipped with sledgehammers tried to break through the door, but their efforts were unsuccessful. Greene found a wooden ladder nearby, and he and about ten Marines used it as a battering ram to force the front doors open. Greene was the first through the door and with the assistance of Lewis Washington, identified and singled out John Brown. Greene later recounted what events occurred next:

Quicker than thought I brought my saber down with all my strength upon [Brown's] head. He was moving as the blow fell, and I suppose I did not strike him where I intended, for he received a deep saber cut in the back of the neck. He fell senseless on his side, then rolled over on his back. He had in his hand a short Sharpe's cavalry carbine. I think he had just fired as I reached Colonel Washington, for the Marine who followed me into the aperture made by the ladder received a bullet in the abdomen, from which he died in a few minutes. The shot might have been fired by someone else in the insurgent party, but I think it was from Brown. Instinctively as Brown fell I gave him a saber thrust in the left breast. The sword I carried was a light uniform weapon, and, either not having a point or striking something hard in Brown's accouterments, did not penetrate. The blade bent double.[21]

The Marine assault on the engine house lasted three minutes. All of the raiders still alive were killed, wounded or taken prisoner. The hostages were freed and the action was over.

Colonel Lee and Jeb Stuart searched the surrounding country for fugitives who had participated in the attack. Few of Brown's associates escaped, and among those who did, some were sheltered by abolitionists in the North, including William Still.[22]

October 19

Robert E. Lee made a synopsis of the events that took place at Harpers Ferry. According to Lee's notes, Lee believed John Brown was a madman: "the plan [raiding the Harpers Ferry Arsenal] was the attempt of a fanatic or madman". Lee also believed that the blacks in the raid were forced by Brown. "The blacks, whom he [John Brown] forced from their homes in this neighborhood, as far as I could learn, gave him no voluntary assistance." Lee attributed John Brown's "temporary success" by creating panic and confusion and by "magnifying" the number of participants involved in the raid.[23]

Trial and execution

Brown was taken to the courthouse in nearby Charles Town for trial. He was found guilty of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, murder, and inciting a slave insurrection, and was hanged on December 2. (This execution was witnessed by the actor John Wilkes Booth, who would later assassinate President Abraham Lincoln.) At the hanging and en route to it, authorities prevented spectators from getting close enough to Brown to hear a final speech, but he surreptitiously slipped his last written words to a jailer:

I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty, land: will never be purged away; but with Blood. I had as I now think: vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed; it might be done.[3]:256

Four other raiders were executed on December 16 and two more on March 16, 1860.

In his last speech, at his trial, he said to the court:

[H]ad I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends, either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class, and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.[3]:212

Southerners had a mixed attitude towards their slaves. Many Southern whites lived in constant fear of another slave insurrection; almost paradoxically, whites claimed that slaves were content in bondage, blaming slave unrest on Northern abolitionists. After the raid Southerners initially lived in fear of slave uprisings and invasion by armed abolitionists. The South's reaction entered the second phase at around the time of Brown's execution. Southerners were relieved that no slaves had volunteered to help Brown, and felt vindicated in their claims that slaves were content. After Northerners had expressed admiration for Brown's motives, with some treating him as a martyr, Southern opinion evolved into what James M. McPherson called "unreasoning fury".[24]

The first Northern reaction among antislavery advocates to Brown's raid was one of baffled reproach. William Lloyd Garrison called the raid "misguided, wild, and apparently insane". But through the trial and his execution, Brown was transformed into a martyr. Henry David Thoreau, in A Plea for Captain John Brown, said, "I think that for once the Sharp's rifles and the revolvers were employed in a righteous cause. The tools were in the hands of one who could use them", and said of Brown, "He has a spark of divinity in him."[25] Though "Harper's Ferry was insane", wrote the religious weekly the Independent, "the controlling motive of his demonstration was sublime". To the South, Brown was a murderer who wanted to deprive them of their property (slaves). The North "has sanctioned and applauded theft, murder, and treason", said De Bow's Review.[26][27]

Brown's raid contributed to Lincoln's election in 1860, and Jefferson Davis "cited the attack as grounds for Southerners to leave the Union, 'even if it rushes us into a sea of blood'".[3]:5

Casualties

John Brown's raiders

- Killed

- John Henry Kagi (Shot and killed while crossing a river. First buried in common grave at Harpers Ferry; reburied 1899 in a common grave near John Brown at North Elba, New York.)

- Jeremiah G. Anderson (At age 26, was mortally wounded and killed by a Marine's bayonet during the final assault on the engine house. Body claimed by Winchester Medical College as a teaching cadaver; last resting place unknown.)

- William Thompson (First buried in common grave at Harpers Ferry; reburied 1899 in a common grave near John Brown at North Elba, New York.)

- Dauphin Thompson (Killed in the storming of the engine house. First buried in common grave at Harpers Ferry; reburied 1899 in a common grave near John Brown at North Elba, New York.)

- Oliver Brown (At age 21, the youngest of John Brown's three sons to participate in the action, he was mortally wounded on the 17th inside the engine house and died the next day. He was first buried in common grave at Harpers Ferry; and reburied in 1899 in a common grave near John Brown at North Elba, New York.)

- Watson Brown (At age 24, was mortally wounded outside the engine house while carrying a white flag to negotiate with the opposing militia; he died two days later. As his body was claimed by Winchester Medical College as a teaching cadaver, Union troops burned the college in an attack during the Civil War. Brown was reburied in 1882 in a grave near his father's in North Elba, New York.)

- Stewart Taylor. Uxbridge, Ontario, Canada (First buried in common grave at Harpers Ferry; reburied 1899 in a common grave near John Brown at North Elba, New York.)

- William Leeman (Shot while trying to escape across the Potomac River. First buried in common grave at Harpers Ferry; reburied 1899 in a common grave near John Brown at North Elba, New York.)

- Lewis Sheridan Leary (A 24-year-old free black, he was mortally wounded while trying to escape across the Shenandoah River. He was stationed in the rifle factory with Kagi. Alleged to be buried at John Brown gravesite at North Elba, New York. Cenotaph memorial in Oberlin, Ohio.)

- Dangerfield Newby (At about 35, he was born into slavery, with a white father who was not his master. He was given permission to move to Ohio along with his mother and siblings, but when he tried to gain freedom for his wife and children, their master refused. This inspired Newby to join Brown's raid. He was the first raider killed. (His body was mutilated; for example, his ears were cut off by someone in the crowd as souvenirs.) First he was buried at Harpers Ferry; reburied in 1899 in a common grave near John Brown at North Elba, New York.)

- Captured, then executed

- John Brown (also wounded) Tried, convicted, and executed by hanging December 2, 1859, in nearby Charles Town.

- Aaron Dwight Stevens (shot and captured October 18. Hanged March 16, 1860 in Charles Town. First buried at Eagleswood Mansion New Jersey; reburied 1899 in a common grave near John Brown at North Elba, New York.[28])

- Edwin Coppock (At age 24, he shot and killed the mayor of Harpers Ferry, Fontaine Beckham, during the raid. He was later executed at Charles Town on December 16, 1859 and was buried in Salem, Ohio.)

- John Anthony Copeland, Jr. (A 25-year-old free black, he joined the raiders along with his uncle Lewis Leary. He was captured during the raid and executed on December 16, 1859, in Charles Town. The body was claimed by Winchester Medical College as a teaching cadaver. The last resting place is unknown. Cenotaph memorial in Oberlin, Ohio.)

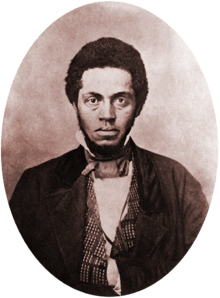

- Shields Green (At about age 23, Green was an escaped slave from South Carolina; captured in the engine house on October 18, 1859 and hanged December 16, 1859 in Charles Town. The body was claimed by Winchester Medical College as a teaching cadaver. The last resting place is unknown. Cenotaph memorial in Oberlin, Ohio.)

- John Edwin Cook (Escaped into Pennsylvania but soon captured. Hanged December 16, 1859 in Charles Town. Body sent to New York.)

- Albert E. Hazlett (Escaped into Pennsylvania but soon captured. Hanged March 16, 1860. Buried at Eagleswood Mansion in Perth Amboy, New Jersey)[28] reburied 1899 in a common grave near John Brown at North Elba, New York

- Escaped and never captured

- Barclay Coppock (Died during US Civil War, 1861.)

- Charles Plummer Tidd (Died during US Civil War, 1862.)

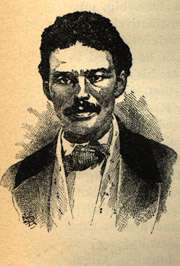

- Osborne Perry Anderson (Served as a recruiter for the Union Army, and wrote a memoir about the raid. Died 1872.)

- Owen Brown (Served as an officer in Union Army. Died January 8, 1889 in Pasadena, California (Brown's Mountain).)

- Francis Jackson Meriam (Served in the army as a captain in the 3rd South Carolina Colored Infantry; died 1865)

Sketch incorrectly showing John Brown Sr with both of his two sons inside the firehouse (one dead and the other dying); Watson died two days later and Oliver died the next day

Sketch incorrectly showing John Brown Sr with both of his two sons inside the firehouse (one dead and the other dying); Watson died two days later and Oliver died the next day Owen Brown

Owen Brown Osborne Perry Anderson

Osborne Perry Anderson John Anthony Copeland

John Anthony Copeland Barclay Coppock

Barclay Coppock Edwin Coppock[29]

Edwin Coppock[29] Shields Green

Shields Green John H. Kagi

John H. Kagi Lewis Sheridan Leary

Lewis Sheridan Leary Dangerfield Newby

Dangerfield Newby

Other casualties, civilian and military

- Killed

- Heyward Shepherd (Free African-American B&O baggage master. Buried in African-American Cemetery on Rt. 11 in Winchester, Virginia, grave is unmarked)[30]

- Thomas Boerly (Townsperson)

- George W. Turner (Townsperson)

- Fontaine Beckham (Harpers Ferry mayor, B&O stationmaster). Mayor Beckham's Will Book called for the liberation of Isaac Gilbert, his wife, and their three children upon his death. When Edwin Coppock killed Beckham the five slaves were freed.[12]:296

- A slave belonging to Colonel Washington was killed.

- A slave belonging to hostage John Allstad was killed. (Some claim the two slaves voluntarily joined Brown's raiders, others say Brown forced them to fight. Regardless, one was killed trying to escape across the Potomac River, the other was wounded and later died in the Charles Town jail.)

- Wounded but survived

- Edward McCabe, Harpers Ferry laborer

- Samuel Young, Charles Town militia

- Martinsburg, Virginia, militia:

- George Murphy

- George Richardson

- G. N. Hammond

- Evan Dorsey

- Nelson Hooper

- George Woollett[3]:292

- U.S. Marine casualties

- Private Luke Quinn (Killed during the storming of the engine house.) Buried in Harpers Ferry Catholic Cemetery on Rte. 340.

- Private Matthew Ruppert (Shot in the face during the storming of the engine house; survived)

Legacy

National Historical Park

In 1944, Harpers Ferry and some surrounding areas were designated as a National Monument. Congress later designated it as the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park in 1963. It is managed by the National Park Service. The park includes the historic town of Harpers Ferry, notable as a center of 19th-century industry and as the scene of the uprising.

Conflicting interpretations

In his day, Brown was seen by abolitionists as admirable in principles, though misguided and ultimately unsuccessful. For the Southern slave states he was a traitor and a threat to the nation.

Even after 160 years there is no consensus on how he is to be seen. The National Park Service plays down Brown and the raid in its literature concerning the Historical Park; Brown is not even mentioned on the home page of the Park. The conflicts over meaning of the events are particularly clear with regard to the Heyward Shepherd monument.

Doubt has been raised as to whether Brown believed his implausible, undermanned attack could succeed, or whether he knew it was doomed yet wanted the publicity it would generate for the abolitionist cause. Certainly he "fail[ed] to take the steps necessary"[3]:239 to make it succeed: he never called on nearby slaves to join the uprising, for example.[3]:236 According to Garrison, "His raid into Virginia looks utterly lacking in common sense—a desperate self-sacrifice for the purpose of giving an earthquake shock to the slave system, and thus hastening the day for a universal catastrophe."[3]:234 The Provisional Constitution he had thousands of copies of printed "was not just a governing document. It was a scare tactic".[3]:238

As Brown wrote in 1851: "The trial for life of one bold and to some extent successful man, for defending his rights in good earnest, would arouse more sympathy throughout the nation than the accumulated wrongs and suffering of more than three millions of our submissive colored population."[3]:240 According to his son Salmon, fifty years later: "He wanted to bring on the war. I have heard him talk of it many times."[3]:238 Certainly Brown saw to it that his arrest, trial, and execution received as much publicity as possible. He "ask[ed] that the incendiary constitution he carried with him be read aloud."[3]:240 "He seemed very fond of talking."[3]:240 Authorities deliberately prevented spectators from being close enough to Brown to hear him speak during his short trip to the gallows, but he did give what became his famous final message to the jailer who had asked for his autograph.[3]:256

Notes

Citations

- "John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry". History.com. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- In many books the town is called "Harper's Ferry." For example, "Col. Robert E. Lee's Report Concerning the Attack at Harper's Ferry, October 19, 1859,"; Horace Greeley, The American Conflict: A History of the Great Rebellion in the United States of America, 1860–64. Volume: 1. (1866), p. 279; French Ensor Chadwick, Causes of the Civil War, 1859–1861 (1906) p. 74; Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln (1950) vol 2 ch 3; James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (1988), p. 201; Stephen W. Sears, Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam (2003) p. 116.

- Horwitz, Tony (2011). Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9780805091533.

- Hoffman, Colonel Jon T., USMC: A Complete History, Marine Corps Association, Quantico, Virginia, (2002), p. 84.

- Taylor, Marian (2004). Harriet Tubman: Antislavery Activist (New ed.). Chelsea House Publishers. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-7910-8340-6.

- "The Kennedy Farmhouse", John Brown website

- "The Harpers Ferry Raid". pbs.org. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (2003) p. 205

- National Park Service History Series. John Brown's Raid (2009), pp. 22–30.

- Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln: Prelude to Civil War, 1859–1861 (1950), vol. 4, pp. 72–73

- National Park Service History Series. John Brown's Raid (2009), p. 16

- Oates, Stephen B. (1984). To Purge this Land with Blood: A Biography of John Brown (2nd ed.). Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0870234587.

- National Park Service. John Brown's Raid (2009), p. 16

- Ted McGee (April 5, 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Beall-Air" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Frances D. Ruth (July 1984). "National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Allstadt House and Ordinary" (PDF). National Park Service. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Horton, James Oliver; Lois E. Horton (2006). Slavery and the Making of America. Oxford University Press USA. p. 162. ISBN 978-0195304510.

- Leuwen, James W. (1999). Lies Across America: what our historic sites get wrong. The New Press. ISBN 1565843444.

- Greeley, Horace (1864). The American Conflict: A History:Part One. p. 292. ISBN 9781417908288.

- National Park Service History Series. John Brown's Raid (2009), pp. 49–50

- Emory M. Thomas, Robert E. Lee: A Biography (1995) p. 180

- Green, Israel (1885). "The Capture of John Brown". North American Review.

- Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. G. M. Rowell & Company, 1887. p. 160

- Col. Robert E. Lee. "Report to the Adjutant General Concerning the Attack at Harper's Ferry". Reproduced in Linder, Douglas O. Famous Trials. University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law.

- James M. McPherson. Battle Cry of Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press (1988), pp. 207–208.

- Norton Anthology of American Literature, Volume B. p. 2057.

- Reynolds, John Brown (2006), p. 340

- James M. McPherson, Battle cry of freedom: the Civil War era (2003), p. 210

- "John Brown's Men Disinterred". New York Times. August 29, 1899.

- Both Coppack photos from A topical history of Cedar County, Iowa, Volume 1 (1910) Clarence Ray Aurner, S. J. Clarke Publishing Company

- Stephen Vincent Benet. John Brown's Body. New York. Rinehart & Co. (1927), p. 33

| Library resources about John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry |

Further reading

- Primary sources

- Lee, Robert E. (October 19, 1859). "Col. Robert E. Lee's Report Concerning the Attack at Harper's Ferry". Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- United States Congress. Senate. Select Committee on the Harper's Ferry Invasion (1860). Mason, John Murray (ed.). "Senate Select Committee Report on the Harper's Ferry Invasion".

- Anderson, Osborne P. (1861). A Voice from Harper's Ferry: A Narrative of Events at Harper's Ferry : with Incidents Prior and Subsequent to Its Capture by Captain Brown and His Men. Boston.

- Green, Israel (1885). "The Capture of John Brown". North American Review.

- Avey, Elijah (1906). The Capture and Execution of John Brown. Chicago: Brethren Publishing House. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

Eyewitness.

- Secondary sources

- Earle, Jonathan. John Brown's Raid on Harpers Ferry: A Brief History with Documents (2008) excerpt and text search

- Field, Ron. Avenging Angel; John Brown's Raid on Harpers Ferry 1859 (2012). Osprey Raid Series #36. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781849087575

- Horwitz, Tony. Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War (2011) Henry Holt and Company

- Nalty, Bernard C. (1959). The United States Marines at Harpers Ferry and in the Civil War (PDF). United States Marine Corps History Division.

- Nevins, Allan. The Emergence of Lincoln: Prelude to Civil War, 1859–1861 (1950), vol 4 of The Ordeal of the Union, esp ch 3 pp 70–97

- Oates, Stephen B. To Purge this Land with Blood: A Biography of John Brown (1984). Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press.

- Potter, David M. The Impending Crisis: 1848–1861 (1976) pp 356–84; Pulitzer Prize winning history

- Reynolds, David S. John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights (2006)

- Villard, Oswald Garrison. John Brown, 1800–1859: A Biography Fifty Years After (1910) 738 pages, full text online

- Thomas, Emory M. Robert E. Lee: A Biography (1995). New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry. |

- Michael E. Ruane (October 14, 2009). "150 Years Later, John Brown's Failed Slave Revolt Marches On". The Washington Post.

- John Brown – 150 Years After Harpers Ferry by Terry Bisson, Monthly Review, October 2009