International sanctions during the Russo-Ukrainian War

International sanctions were imposed during the Russo-Ukrainian War by a large number of countries against Russia and Crimea following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which began in late February 2014. The sanctions were imposed by the United States, the European Union (EU) and other countries and international organisations against individuals, businesses and officials from Russia and Ukraine.[1] Russia responded with sanctions against a number of countries, including a total ban on food imports from the EU, United States, Norway, Canada and Australia.

Countries that have introduced sanctions on Russia:

The sanctions by the European Union and United States continue to be in effect as of May 2019.[2] In December 2019, the EU announced the extension of sanctions until 31 July 2020.[3][4]

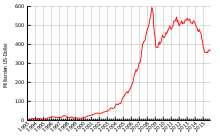

The sanctions contributed to the collapse of the Russian ruble and the Russian financial crisis.[5] They also caused economic damage to a number of EU countries, with total losses estimated at €100 billion (as of 2015).[6] As of 2014, Russia's Finance Minister announced that the sanctions had cost Russia $40 billion, with another $100 billion loss in 2014 taken due to the decrease in the price of oil the same year driven by the 2010s oil glut.[7] Following the latest sanctions imposed in August 2018, economic losses incurred by Russia amount to some 0.5–1.5% of foregone GDP growth.

In addition to the sanctions, Russian President Vladimir Putin has accused the United States of conspiring with Saudi Arabia to intentionally weaken the Russian economy by decreasing the price of oil.[8] By mid-2016, Russia had lost an estimated $170 billion due to financial sanctions, with another $400 billion in lost revenues from oil and gas.[9]

According to Ukrainian officials,[lower-alpha 1] the sanctions forced Russia to change its approach towards Ukraine and undermined the Russian military advances in the region.[10][11] Representatives of these countries say that they will lift sanctions against Russia only after Moscow fulfils the Minsk II agreements.[12][13][14]

Background

| Russo-Ukrainian War |

|---|

|

| Main topics |

| Related topics |

In response to the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, some governments and international organisations, led by the United States and European Union, imposed sanctions on Russian individuals and businesses. As the unrest expanded into other parts of Eastern Ukraine, and later escalated into the ongoing war in the Donbass region, the scope of the sanctions increased. Overall, three types of sanctions were imposed: ban on provision of technology for oil and gas exploration, ban on provision of credits to Russian oil companies and state banks, travel restrictions on the influential Russian citizens close to President Putin and involved in the annexation of Crimea.[15] The Russian government responded in kind, with sanctions against some Canadian and American individuals and, in August 2014, with a total ban on food imports from the European Union, United States, Norway, Canada and Australia.

Sanctions against Russian and Ukrainian individuals, companies and officials

First round : March/April 2014

On 6 March 2014, U.S. President Barack Obama, invoking, inter alia, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act and the National Emergencies Act, signed an executive order declaring a national emergency and ordering sanctions, including travel bans and the freezing of U.S. assets, against not-yet-specified individuals who had "asserted governmental authority in the Crimean region without the authorization of the Government of Ukraine" and whose actions were found, inter alia, to "undermine democratic processes and institutions in Ukraine".[16][17]

On 17 March 2014, the U.S., the EU and Canada introduced specifically targeted sanctions,[18][19][20] the day after the Crimean referendum and a few hours before Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a decree recognizing Crimea as an independent state, laying the groundwork for its annexation of Crimea by Russia. The principal EU sanction aimed to "prevent the entry into … their territories of the natural persons responsible for actions which undermine … the territorial integrity … of Ukraine, and of natural persons associated with them, as listed in the Annex".[18] The EU imposed its sanctions "in the absence of de-escalatory steps by the Russian Federation" in order to bring an end to the violence in eastern Ukraine. The EU at the same time clarified that the EU "remains ready to reverse its decisions and reengage with Russia when it starts contributing actively and without ambiguities to finding a solution to the Ukrainian crisis".[21] These 17 March sanctions were the most wide-ranging sanctions used against Russia since the 1991 fall of the Soviet Union.[22] Japan also announced sanctions against Russia, which included the suspension of talks regarding military matters, space, investment, and visa requirements.[23] A few days later, the US government expanded the sanctions.[24]

On 19 March, Australia imposed sanctions against Russia after its annexation of Crimea. These sanctions targeted financial dealings and travel bans on those who have been instrumental in the Russian threat to Ukraine's sovereignty.[25] Australian sanctions were expanded on 21 May.[26]

In early April, Albania, Iceland and Montenegro, as well as Ukraine, imposed the same restrictions and travel bans as those of the EU on 17 March.[27] Igor Lukšić, foreign minister of Montenegro, said that despite a "centuries old-tradition" of good ties with Russia, joining the EU in imposing sanctions had "always been the only reasonable choice".[28] Slightly earlier in March, Moldova imposed the same sanctions against former president of Ukraine Viktor Yanukovych and a number of former Ukrainian officials, as announced by the EU on 5 March.[29]

In response to the sanctions introduced by the United States and the EU, the State Duma (Russian parliament) unanimously passed a resolution asking for all members of the Duma be included on the sanctions list.[30] The sanctions were expanded to include prominent Russian businessmen and women a few days later.

Second round: April 2014

On 10 April, the Council of Europe suspended the voting rights of Russia's delegation.[32]

On 28 April, the United States imposed a ban on business transactions within its territory on 7 Russian officials, including Igor Sechin, executive chairman of the Russian state oil company Rosneft, and 17 Russian companies.[33]

On the same day, the EU issued travel bans against a further 15 individuals.[34] The EU also stated the aims of EU sanctions as:

sanctions are not punitive, but designed to bring about a change in policy or activity by the target country, entities or individuals. Measures are therefore always targeted at such policies or activities, the means to conduct them and those responsible for them. At the same time, the EU makes every effort to minimise adverse consequences for the civilian population or for legitimate activities.[35]

Third round: 2014–present

In response to the escalating War in Donbass, on 17 July 2014 the United States extended its transactions ban to two major Russian energy firms, Rosneft and Novatek, and to two banks, Gazprombank and Vnesheconombank.[36] United States also urged EU leaders to join the third wave[37] leading EU to start drafting European sanctions a day before.[38][39] On 25 July, the EU officially expanded its sanctions to an additional 15 individuals and 18 entities,[40] followed by an additional eight individuals and three entities on 30 July.[41] On 31 July 2014 the EU introduced the third round of sanctions which included an embargo on arms and related material, and embargo on dual-use goods and technology intended for military use or a military end user, a ban on imports of arms and related material, controls on export of equipment for the oil industry, and a restriction on the issuance of and trade in certain bonds, equity or similar financial instruments on a maturity greater than 90 days (In September 2014 lowered to 30 days)[42]

On 24 July 2014, Canada targeted Russian arms, energy and financial entities.[43]

On 5 August 2014, Japan froze the assets of "individuals and groups supporting the separation of Crimea from Ukraine" and restrict imports from Crimea. Japan also froze funds for new projects in Russia in line with the policy of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.[44]

On 8 August 2014, Australian prime minister Tony Abbott announced that Australia is "working towards" tougher sanctions against Russia, which should be implemented in the coming weeks.[45][46]

On 12 August 2014, Norway adopted the tougher sanctions against Russia that were imposed by the EU and the United States on 12 August 2014. Although Norway is not a part of the EU, the Norwegian Foreign Minister Børge Brende said that it would impose restrictions similar to the EU's 1 August sanctions. Russian state-owned banks will be banned from taking long-term and mid-term loans, arms exports will be banned and supplies of equipment, technology and assistance to the Russian oil sector will be prohibited.[47]

On 14 August 2014, Switzerland expanded sanctions against Russia over its threat to Ukraine's sovereignty. Swiss government added 26 more Russians and pro-Russian Ukrainians to the list of sanctioned Russian citizens that was first announced after Russia's annexation of Crimea.[48] On 27 August 2014 Switzerland further expanded their sanctions against Russia. The Swiss government said it is expanding measures to prevent the circumvention of sanctions relating to the situation in Ukraine to include the third round of sanctions imposed by the EU in July. The Swiss government also stated that 5 Russian banks (Sberbank, VTB, Vnesheconombank (VEB), Gazprombank and Rosselkhoz) will require authorisation to issue long-term financial instruments in Switzerland.[49] On 28 August 2014, Switzerland amended its sanctions to include the sanctions imposed by the EU in July.[49]

On 14 August 2014, Ukraine passed a law introducing Ukrainian sanctions against Russia.[50][51] The law includes 172 individuals and 65 entities in Russia and other countries for supporting and financing "terrorism" in Ukraine, though actual sanctions would need approval from Ukraine's National Security and Defense Council.

On 11 September 2014, US President Obama said that the United States would join the EU in imposing tougher sanctions on Russia's financial, energy and defence sectors.[52] On 12 September 2014, the United States imposed sanctions on Russia's largest bank (Sberbank), a major arms maker and arctic (Rostec), deepwater and shale exploration by its biggest oil companies (Gazprom, Gazprom Neft, Lukoil, Surgutneftegas and Rosneft). Sberbank and Rostec will have limited ability to access the US debt markets. The sanction on the oil companies seek to ban co-operation with Russian oil firms on energy technology and services by companies including Exxon Mobil Corp. and BP Plc.[53]

On 24 September 2014, Japan banned the issue of securities by 5 Russian banks (Sberbank, VTB, Gazprombank, Rosselkhozbank and development bank VEB) and also tightened restrictions on defence exports to Russia.[54]

On 3 October 2014, US Vice President Joe Biden said that "It was America's leadership and the president of the United States insisting, oft times almost having to embarrass Europe to stand up and take economic hits to impose costs"[55] and added that "And the results have been massive capital flight from Russia, a virtual freeze on foreign direct investment, a ruble at an all-time low against the dollar, and the Russian economy teetering on the brink of recession. We don't want Russia to collapse. We want Russia to succeed. But Putin has to make a choice. These asymmetrical advances on another country cannot be tolerated. The international system will collapse if they are."[56]

On 18 December 2014, the EU banned some investments in Crimea, halting support for Russian Black Sea oil and gas exploration and stopping European companies from purchasing real estate or companies in Crimea, or offering tourism services.[57] On 19 December 2014, US President Obama imposed sanctions on Russian-occupied Crimea by executive order prohibiting exports of US goods and services to the region.[58]

On 16 February 2015, the EU increased its sanction list to cover 151 individuals and 37 entities.[59] Australia indicated that it would follow the EU in a new round of sanctions. If the EU sanctioned new Russian and Ukrainian entities then Australia would keep their sanctions in line with the EU.

On 18 February 2015, Canada added 37 Russian citizens and 17 Russian entities to its sanction list. Rosneft and the deputy minister of defence, Anatoly Antonov, were both sanctioned.[60][61] In June 2015 Canada added three individuals and 14 entities, including Gazprom.[62] Media suggested the sanctions were delayed because Gazprom was a main sponsor of the 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup then concluding in Canada.[63]

In September 2015, Ukraine sanctioned more than 388 individuals, over 105 companies and other entities. In accordance with the August 2015 proposals promulgated by the Security Service of Ukraine and the Order of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine No. 808-p dated 12 August 2015, Ukraine, on 2 September 2015, declared Russia an enemy of Ukraine. Also on 16 September 2015, Ukraine President Petro Poroshenko issued a decree that named nearly 400 individuals, more than 90 companies and other entities to be sanctioned for the Russia's "criminal activities and aggression against Ukraine."[64][65][66][67]

Sanctions against Crimea

The United States, Canada, the European Union and other European countries (including Ukraine) imposed economic sanctions specifically targeting Crimea. Sanctions prohibit the sale, supply, transfer, or export of goods and technology in several sectors, including services directly related to tourism and infrastructure. They list seven ports where cruise ships cannot dock.[68][69][70][71][72] Sanctions against Crimean individuals include travel bans and asset freezes. Visa and MasterCard have stopped service in Crimea between December 2014 and April 2015.[73]

In September 2016 Pursuant to Executive Order 13685, OFAC designated Russian shipping company Sovfracht-Sovmortrans Group and its subsidiary, Sovfracht for operating in Crimea.[74]

Sanctions over Ukrainians held by Russia

In April 2016, Lithuania sanctioned 46 individuals who were involved in the detention and sentencing of Ukrainian citizens Nadiya Savchenko, Oleh Sentsov, and Olexandr Kolchenko. Lithuanian Foreign Minister Linas Linkevičius said that his country wanted to "focus attention on the unacceptable and cynical violations of international law and human rights in Russia. [...] It would be more effective if the blacklist became Europe-wide. We hope to start such a discussion."[75]

Opposition to sanctions

Whilst Russia's annexation of Crimea is the primary justification for sanctions, this is at odds with the strong local support for the transfer of territory by the public of Crimea themselves.[76][77]

Italy, Hungary, Greece, France, Cyprus and Slovakia are among the EU states most skeptical about the sanctions and have called for review of sanctions.[78] The Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán stated that Europe "shot itself in the foot" by introducing economic sanctions.[79] Bulgarian Prime Minister Boiko Borisov stated, "I don't know how Russia is affected by the sanctions, but Bulgaria is affected severely";[80] Czech President Miloš Zeman[81] and Slovakian Prime Minister Robert Fico[82] also said that the sanctions should be lifted. In October 2017, the Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade Péter Szijjártó added that the sanctions "were totally unsuccessful because Russia is not on its knees economically, but also because there have been many harms to our own economies and, politically speaking, we have had no real forward progress regarding the Minsk agreement".[83]

In 2015, the Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras repeatedly said that Greece would seek to mend ties between Russia and EU through European institutions. Tsipras also said that Greece was not in favour of Western sanctions imposed on Russia, adding that it risked the start of another Cold War.[84][85]

A number of business figures in France and Germany have opposed the sanctions.[86][87][88] The German Economy Minister Sigmar Gabriel said that the Ukrainian crisis should be resolved by dialogue rather than economic confrontation,[89] later adding that the reinforcement of anti-Russian sanctions will "provoke an even more dangerous situation… in Europe".[90]

Paolo Gentiloni, Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, said that the sanctions "are not the solution to the conflict".[91] In January 2017, Swiss Economics Minister and former President of Switzerland Johann Schneider-Ammann stated his concern about the sanctions' harm to the Swiss economy, and expressed hope that they will soon come to an end.[92] Some companies, most notably Siemens Gas Turbine Technologies LLC and Lufthansa Service Holding were reported to attempt bypassing the sanctions and exporting power generation turbines to the annexed Crimea.[93]

In August 2015, the British think tank Bow Group released a report on sanctions, calling for the removal of them. According to the report, the sanctions have had "adverse consequences for European and American businesses, and if they are prolonged... they can have even more deleterious effects in the future"; the potential cost of sanctions for the Western countries has been estimated as over $700 billion.[94]

In June 2017, Germany and Austria criticized the U.S. Senate over new sanctions against Russia that target the planned Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia to Germany,[95][96] stating that the United States was threatening Europe's energy supplies (see also Russia in the European energy sector).[97] In a joint statement Austria's Chancellor Christian Kern and Germany's Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel said that "Europe's energy supply is a matter for Europe, and not for the United States of America."[98] They also said: "To threaten companies from Germany, Austria and other European states with penalties on the U.S. market if they participate in natural gas projects such as Nord Stream 2 with Russia or finance them introduces a completely new and very negative quality into European-American relations."[99]

In May 2018, the vice chairman of Free Democratic Party of Germany and the Vice President of the Bundestag Wolfgang Kubicki said that Germany should "take a first step towards Russia with the easing of the economic sanctions" because "this can be decided by Germany alone" and "does not need the consent of others".[100]

In February 2019, advisor to Municipal Councilor of Municipality of Verona, member of House of Representatives Vito Comencini said that the anti-Russian sanctions have caused significant damage to the Italian economy, with the result that the country suffers losses every day in the amount of millions of euros.[101]

Efforts to lift sanctions

France announced in January 2016 that it wanted to lift the sanctions in mid-2016. Earlier, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry mentioned a possible lifting of sanctions.[102]

In June 2016, the French Senate voted to urge its government to "gradually and partially" lift the EU sanctions on Russia, although the vote was non-binding.[103]

However, in September 2016, the EU extended its sanctions, for another six months, against Russian officials and pro-Moscow separatists in Ukraine.[104] An EU asset freeze on ex-Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych was upheld by the bloc's courts.[104] On 13 March 2017, the EU extended the asset freeze and travel bans on 150 people until September 2017.[105] The sanctions include Yanukovych and senior members of his administration.[105]

As Trump's National Security Advisor, Michael T. Flynn was an important link in the connections between Putin and Trump in the "Ukraine peace plan", an unofficial plan "organized outside regular diplomatic channels....at the behest of top aides to President Putin". This plan, aimed at easing the sanctions imposed on Russia, progressed from Putin and his advisors to Ukrainian politician Andrey Artemenko, Felix Sater, Michael Cohen, and Flynn, where he would have then presented it to Trump. The New York Times reported that Sater delivered the plan "in a sealed envelope" to Cohen, who then passed it on to Flynn in February 2017, just before his resignation.[106]

On 19 June 2017, the EU again extended sanctions for another year that prohibit EU businesses from investing in Crimea, and which target tourism and imports of products from Crimea.[107]

In November 2017, the Secretary General of the Council of Europe Thorbjørn Jagland said that the Council of Europe considered lifting the sanctions on Russia due to concerns that Russia may leave the organization, which would be "a big step back for Europe".[108] Jagland was also criticized of "caving in to blackmail" by other Council members for his conciliatory approach to Russia.[108]

On 9 October 2018, the council's parliamentary assembly voted to postpone the decision on whether Russia's voting rights should be restored.[109]

On 8 March 2019, the Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte stated that Italy is working on lifting the sanctions, which "the ruling parties in Rome say are ineffective and hurt the Italian economy".[110]

Other sanctions on Russia

In December 2012, the United States enacted the Magnitsky Act, intended to punish Russian officials responsible for the death of Russian tax accountant Sergei Magnitsky in a Moscow prison in 2009 by prohibiting their entrance to the United States and their use of its banking system.[111] 18 individuals were originally affected by the Act. In December 2016, Congress enacted the Global Magnitsky Act to allow the US Government to sanction foreign government officials implicated in human rights abuses anywhere in the world.[112] On 21 December 2017, 13 additional names were added to the list of sanctioned individuals, not just Russians. Other countries passed similar laws to ban foreigners deemed guilty of human rights abuses from entering their countries.

On 29 December 2016, US President Barack Obama signed an order that expels 35 Russian diplomats, locks down two Russian diplomatic compounds, and expands sanctions against Russia for its interference in the 2016 United States elections.[113][114][115][116]

In August 2017, United States Congress passed the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act that imposed new sanctions on Russia for interference in the 2016 elections and its involvement in Ukraine and Syria. The Act prevents the easing, suspending or ending of sanctions by the President without the approval of the United States Congress.[117][118]

In January 2018 the EU sanctioned entities who participated in the construction of the Crimea Bridge: Institute Giprostroymost, the firm which designed the bridge; Mostotrest, which has a contract to maintain the bridge; Zaliv Shipyard, which built a railroad line to the bridge; Stroygazmontazh Corporation, the main construction company that built the bridge; a subsidiary of Stroygazmontazh called Stroygazmontazh-Most and VAD, which built the roadway over the bridge, as well as access roads.[119]

On 15 March 2018, Trump imposed financial sanctions under the Act on the 13 Russian government hackers and front organizations that had been indicted by Mueller's investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections.[120]

In March 2018, 29 Western countries and NATO expelled in total at least 149 Russian diplomats, including 60 by the United States, in response to the poisoning of Skripal and his daughter on 4 March in the United Kingdom, which has been blamed on Russia.[121] Other measures were also taken.

On 6 April 2018, the United States imposed economic sanctions on seven Russian oligarchs and 12 companies they control, accusing them of "malign activity around the globe", along with 17 top Russian officials, the state-owned weapons-trading company Rosoboronexport and Russian Financial Corporation Bank (RFC Bank). High-profile names on the list include Oleg Deripaska and Kiril Shamalov, Putin's ex-son-in-law, who married Putin's daughter Katerina Tikhonova in February 2013. The press release stated: "Deripaska has been investigated for money laundering, and has been accused of threatening the lives of business rivals, illegally wiretapping a government official, and taking part in extortion and racketeering. There are also allegations that Deripaska bribed a government official, ordered the murder of a businessman, and had links to a Russian organized crime group."[122] Other names on the list include: Oil tycoon Vladimir Bogdanov, Suleiman Kerimov, who faces money-laundering charges in France for allegedly bringing hundreds of millions of euros into the country without reporting the money to tax authorities, Igor Rotenberg, principal owner of Russian oil and gas drilling company Gazprom Burenie, Andrei Skoch, a deputy in the State Duma. U.S. officials said he has longstanding ties to Russian organized criminal groups, Viktor Vekselberg, founder and chairman of the Renova Group, asset management company,[122][123] and Aleksandr Torshin.[124]

In August 2018 following the poisoning of Sergey Skripal, U.S Department of Commerce imposed further sanctions on dual-use exports to Russia which deemed to be sensitive on national security grounds, including gas turbine engines, integrated circuits, and calibration equipment used in avionics. Until that moment, such exports were considered on a case-by-case basis. Following the introduction of these sanctions, the default position is of denial.[125] Also, on September that year list of companies in the space and defense industry came under sanctions, including: AeroComposit, Divetechnoservices, Scientific-Research Institute "Vektor", Nilco Group, Obinsk Research and Production Enterprise, Aviadvigatel, Information Technology and Communication Systems (Infoteks), Scientific and Production Corporation of Precision Instruments Engineering and Voronezh Scientific Research Institute "Vega“, whom are forbidden from doing business with.[126]

In March 2019, United States imposed sanctions on persons and companies involved in the Russian shipbuilding industry in response to the Kerch Strait incident: Yaroslavsky Shipbuilding Plant, Zelenodolsk Shipyard Plant, AO Kontsern Okeanpribor, PAO Zvezda (Zvezda), AO Zavod Fiolent (Fiolent), GUP RK KTB Sudokompozit (Sudokompozit), LLC SK Consol-Stroi LTD and LLC Novye Proekty. Also, the U.S. targeted persons involved in the 2018 Donbass general elections.[127]

On 2 August 2019, U.S State Department announced additional sanctions together with an executive order signed by President Trump which gives the Department of Treasury and the Department of Commerce the authority to implement the sanctions. The sanctions forbid granting Russia loans or other assistance from international financial institutions, prohibition on U.S banks buy non-ruble denominated bonds issued by the Russia after 26 August and lending non-ruble denominated funds to Russia and licensing restrictions for exports of items for chemical and biological weapons proliferation reasons.[128]

In September 2019 pursuant to Executive Order 13685 Maritime Assistance LLC was placed under sanctions due to its export of fuel to Syria as well as for providing support to Sovfracht, another company sanctioned for operating in Crimea.[74][129] Later at the same month, United States sanctioned two Russian citizens as well as three companies, Autolex Transport, Beratex Group and Linburg Industries in connection with the Russian interference in the 2016 United States election.[130]

Consequences and assessment

The sanctions introduced both by and against Russia slowed down the trade between Russia and EU, causing damage to both Russian and European economy.

Effect on Russia

The economic sanctions are generally believed to have helped weaken the Russian economy slightly and to intensify the challenges that Russia was facing.

A 2015 data analysis suggested Russia's entry into a recession, with negative GDP growth of −2.2% for the first quarter of 2015, as compared to the first quarter of 2014. Further, the combined effect of the sanctions and the rapid decline in oil prices in 2014 has caused significant downward pressure on the value of the ruble and flight of capital out of Russia. At the same time, the sanctions on access to financing have forced Russia to use part of its foreign exchange reserves to prop up the economy. These events forced the Central Bank of Russia to stop supporting the value of the ruble and increase interest rates.

Some believe that Russia's ban on western imports had the additional effect on these challenging events as the embargo led to higher food prices and further inflation in addition to the effects of decreased value of the ruble which had already raised the price of imported goods.[132]

In 2016 agriculture has surpassed the arms industry as Russia's second largest export sector after oil and gas.[133]

Effect on US and EU countries

As of 2015, the losses of EU have been estimated as at least €100 billion.[6] The German business sector, with around 30,000 workplaces depending on trade with the Russian Federation, also reported being affected significantly by the sanctions.[134] The sanctions affected numerous European market sectors, including energy, agriculture,[135] and aviation among others.[136] In March 2016, the Finnish farmers' union MTK stated that the Russian sanctions and falling prices have put farmers under tremendous pressure. Finland's Natural Resources Institute LUKE has estimated that last year farmers saw their incomes shrink by at least 40 percent compared to the previous year.[137]

In February 2015, Exxon Mobil reported losing about $1 billion due to Russian sanctions.[138]

In 2017, the UN Special Rapporteur Idriss Jazairy published a report on the impact of sanctions, stating that the EU countries were losing about "3.2 billion dollars a month" due to them. He also noted that the sanctions were "intended to serve as a deterrent to Russia but run the risk of being only a deterrent to the international business community, while adversely affecting only those vulnerable groups which have nothing to do with the crisis" (especially people in Crimea, who "should not be made to pay collectively for what is a complex political crisis over which they have no control").[139][140][141]

Russian counter-sanctions

Three days after the first sanctions against Russia, on 20 March 2014, the Russian Foreign Ministry published a list of reciprocal sanctions against certain American citizens, which consisted of ten names, including Speaker of the House of Representatives John Boehner, Senator John McCain, and two advisers to Barack Obama. The ministry said in the statement, "Treating our country in such way, as Washington could have already ascertained, is inappropriate and counterproductive", and reiterated that sanctions against Russia would have a boomerang effect.[142] On 24 March, Russia banned thirteen Canadian officials, including members of the Parliament of Canada, from entering the country.[143]

On 6 August 2014,[144] Putin signed a decree "On the use of specific economic measures", which mandated an effective embargo for a one-year period on imports of most of the agricultural products whose country of origin had either "adopted the decision on introduction of economic sanctions in respect of Russian legal and (or) physical entities, or joined same".[145][146] The next day, the Russian government ordinance was adopted and published with immediate effect,[147] which specified the banned items as well as the countries of provenance: the United States, the EU, Norway, Canada and Australia, including a ban on fruit, vegetables, meat, fish, milk and dairy imports. Prior to the embargo, food exports from the EU to Russia were worth around €11.8 billion, or 10% of the total EU exports to Russia. Food exports from the United States to Russia were worth around €972 million. Food exports from Canada were worth around €385 million. Food exports from Australia, mainly meat and live cattle, were worth around €170 million per year.[148][149]

Russia had previously taken a position that it would not engage in "tit-for-tat" sanctions, but, announcing the embargo, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev said, "There is nothing good in sanctions and it was not an easy decision to take, but we had to do it." He indicated that sanctions relating to the transport manufacturing sector were also being considered. United States Treasury spokesperson David Cohen said that sanctions affecting access to food were "not something that the US and its allies would ever do".[150]

On the same day, Russia announced a ban on the use of its airspace by Ukrainian aircraft.[148]

In January 2015, it became clear that Russian authorities would not allow a Member of the European Parliament, Lithuanian MEP Gabrielius Landsbergis, make a visit to Moscow due to political reasons.[151]

In March 2015, Latvian MEP Sandra Kalniete and Speaker of the Polish Senate Bogdan Borusewicz were both denied entry into Russia under the existing sanctions regime, and were thus unable to attend the funeral of murdered opposition politician Boris Nemtsov.[152]

After a member of the German Bundestag was denied entry into Russia in May 2015, Russia released a blacklist to European Union governments of 89 politicians and officials from the EU who are not allowed entry into Russia under the present sanctions regime. Russia asked for the blacklist to not be made public.[153] The list is said to include eight Swedes, as well as two MPs and two MEPs from the Netherlands.[154] Finland's national broadcaster Yle published a leaked German version of the list.[155][156]

In response to this publication, British politician Malcolm Rifkind (whose name was included on the Russian list) commented: "It shows we are making an impact because they wouldn't have reacted unless they felt very sore at what had happened. Once sanctions were extended, they've had a major impact on the Russian economy. This has happened at a time when the oil price has collapsed and therefore a main source of revenue for Mr Putin has disappeared. That's pretty important when it comes to his attempts to build up his military might and to force his neighbours to do what they're told." He added, "If there had to be such a ban, I am rather proud to be on it – I'd be rather miffed if I wasn't."[157] Another person on the list, Swedish MEP Gunnar Hökmark, remarked that he was proud to be on the list and said "a regime that does this does it because it is afraid, and at heart it is weak".[158]

With regard to Russia's entry ban on European politicians, a spokesperson from the EU said, "The list with 89 names has now been shared by the Russian authorities. We don't have any other information on legal basis, criteria and process of this decision. We consider this measure as totally arbitrary and unjustified, especially in the absence of any further clarification and transparency."[159]

On 29 June 2016, Russian president Vladimir Putin signed a decree that extended the embargo on the countries already sanctioned until 31 December 2017.[160]

According to a 2020 study, the Russian counter-sanctions did not just serve Russia's foreign policy goals, but also facilitated Russia's protectionist policy.[161]

List of sanctioned individuals

Sanctioned individuals include notable and high-level central government personnel and businessmen on all sides. In addition, companies suggested for possible involvement in the controversial issues have also been sanctioned.

See also

Notes

- Liubov Nepop, the Head of the Ukrainian Mission to the EU, and Petro Poroshenko, the president of Ukraine

References

- Overland, Indra; Fjaertoft, Daniel (2015). "Financial Sanctions Impact Russian Oil, Equipment Export Ban's Effects Limited". Oil and Gas Journal. 113 (8): 66–72. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- "INSIGHT: Russia Sanctions". www.skuld.com. SKULD, Oslo. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- "EU extends economic sanctions against Russia by another 6 months". RT International. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- "Russia: EU prolongs economic sanctions by six months". consilium.europa.eu. European Council. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- "Russia’s rouble crisis poses threat to nine countries relying on remittances Archived 9 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine ". The Guardian. 18 January 2015.

- Sharkov, Damien (19 June 2015). "Russian sanctions to 'cost Europe €100bn'". Newsweek.com. Archived from the original on 2 June 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- Smith, Geoffrey. "Finance Minister: oil slump, sanctions cost Russia $140 billion a year." 24 November 2014.

- Владимир Путин: мы сильнее, потому что правы.

- Pettersen, Trude. "Russia loses $600 billion on sanctions and low oil prices." The Barents Observer. May 2016.

- "When the sanctions regime appeared to cost almost nothing to EU trade volume... together with Ukrainian resistance, it forced Russia to change its approach towards Ukraine... So far, an approach comprised of EU unity and strong solidarity with Ukraine, as well as resistance and reforms implementation, has proved to be the most efficient way to stop Russian military advances." – Liubov Nepop, the Head of the Ukrainian Mission to the EU (source Archived 1 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine)

- "... sanctions and heroism of our warriors are the key elements of deterring the Russian aggression" --the president of Ukraine Petro Poroshenko (source Archived 13 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine )

- "Obama calls on NATO, EU to boost support for Ukraine". Unian.info. 8 July 2016. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- "Austrian foreign minister calls for improving relationship with Moscow". Reuters. 19 June 2016. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- "Sanctions to be lifted from Russia after implementation of Minsk Agreements – Nuland". Interfax-Ukraine. 18 May 2016. Archived from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Overland, Indra; Kubayeva, Gulaikhan (1 January 2018). Did China Bankroll Russia's Annexation of Crimea? The Role of Sino-Russian Energy Relations. pp. 95–118. ISBN 9783319697895. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Executive Order – Blocking Property of Certain Persons Contributing to the Situation in Ukraine Archived 8 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine The White House, 6 March 2014.

- Holland, Steve (6 March 2014). "UPDATE 4-Obama warns on Crimea, orders sanctions over Russian moves in Ukraine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "COUNCIL DECISION 2014/145/CFSP of 17 March 2014 concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Union. 17 March 2014. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "U.S. and Europe Step Up Sanctions on Russian Officials". New York Times. 17 March 2014. Archived from the original on 24 November 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- "Sanctions List". Prime Minister of Canada Stephen Harper. 17 March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "EU sanctions against Russia over Ukraine crisis". European External Action Service. Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- Katakey, Rakteem (25 March 2014). "Russian Oil Seen Heading East Not West in Crimea Spat". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- "Japan imposes sanctions against Russia over Crimea independence". Fox News. Associated Press. 18 March 2014. Archived from the original on 1 December 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "US imposes second wave of sanctions on Russia". jnmjournal.com. 20 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "Australia imposes sanctions on Russians after annexation of Crimea from Ukraine". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 19 March 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- Minister for Foreign Affairs (Australia) (21 May 2014). "Further sanctions to support Ukraine". Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- "Declaration by the High Representative on behalf of the European Union on the alignment of certain third countries with the Council Decision 2014/145/CFSPconcerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 11 April 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- Rettman, Andrew (17 December 2014). "Montenegro-EU talks advance in Russia's shadow". EUobserver. Archived from the original on 17 July 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- "Moldova joined EU sanctions against former Ukrainian officials". Teleradio Moldova. 20 March 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- "All Russian MPs volunteer to be subject to US, EU sanctions". 2014-03-18. Archived from the original on 24 November 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Harding, Luke (10 April 2014). "Russia delegation suspended from Council of Europe over Crimea". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "U.S. levels new sanctions against Russian officials, companies". Haaretz. 28 April 2014. Archived from the original on 29 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- "EU strengthens sanctions against actions undermining Ukraine's territorial integrity". International Trade Compliance. 28 April 2014. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- "EU restrictive measures" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 29 April 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- "Third Wave of Sanctions Slams Russian Stocks". Moscow Times. 17 July 2014. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- Marchak, Daria (15 July 2014). "EU Readies Russia Sanctions Amid U.S. Pressure on Ukraine". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- "EU summit: Leaked draft of new Russia sanctions". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "EU Draft Urges Deeper Sanctions Against Russia". International Business Times UK. 16 July 2014. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine".

- "Council Decision 2014/508/CFSP of 30 July 2014 amending Decision 2014/145/CFSP concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine".

- http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:JOL_2014_229_R_0001&from=EN Archived 3 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine COUNCIL REGULATION (EU) No 833/2014

- "Ukraine crisis: U.S., EU, Canada announce new sanctions against Russia". cbc.ca. Thomson Reuters. 29 July 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "Japan Formally OKs Additional Russia Sanctions". ABC News. 5 August 2014. Archived from the original on 6 August 2014.

- Rosie Lewis (8 August 2014). "Australia 'working towards' tougher sanctions against Russia: Abbott". The Australian. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "Prime Minister Tony Abbott arrives in Netherlands, flags tougher sanctions against Russia over MH17". ABC News. 11 August 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- Saleha Mohsin (12 August 2014). "Norway 'Ready to Act' as Putin Sanctions Spark Fallout Probe". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- Switzerland Expands Sanctions Against Russia Over Ukraine Crisis RFERL: Switzerland Expands Sanctions Against Russia Over Ukraine Crisis

- "Situation in Ukraine: Federal Council decides on further measures to prevent the circumvention of international sanctions". Bern, Switzerland: news.admin.ch. 27 August 2014. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014.

- RFE/RL (14 August 2014). "Ukraine Passes Law on Russia Sanctions, Gas Pipelines". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "Ukraine approves law on sanctions against Russia". Reuters. 14 August 2014. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- Lamarque, Kevin (11 September 2014). "Obama says U.S. to outline new Russia sanctions on Friday". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- Arshad, Mohammed (12 September 2014). "U.S. steps up sanctions on Russia over Ukraine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- Takahashi, Maiko (25 September 2014). "U.S. Japan Steps Up Russia Sanctions, Protests Island Visit". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- "Biden says US 'embarrassed' EU into sanctioning Russia over Ukraine Archived 5 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine ". RT. 4 October 2014.

- Biden, Joe (3 October 2014). "Remarks by the Vice President at the John F. Kennedy Forum". www.whitehouse.gov. The White House – President Barack Obama. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- Adrian Croft; Robin Emmott (18 December 2014). "EU bans investment in Crimea, targets oil sector, cruises". Reuters. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "US slaps trade ban on Crimea over Russia 'occupation'". Channel NewsAsia. AFP/fl. 20 December 2014. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "New EU Sanctions Hit 2 Russian Deputy DMs". Defense News. 16 February 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "Expanded Sanctions List". Ottawa, Ontario: pm.gc.ca. 17 February 2015. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015.

- "Ukraine conflict: Russia rebuffs new Canadian sanctions as 'awkward'". CBC News. 18 February 2015.

- "Expanded Sanctions List". pm.gc.ca. 29 June 2015. Archived from the original on 20 August 2015.

- Berthiaume, Lee (8 July 2015). "Russian sponsor of FIFA world cup sanctioned as tournament ended". Ottawa Citizen. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "Президент увів у дію санкції проти Росії: Підписавши указ, Порошенко затвердив рішення РНБО від 2 вересня". The Ukrainian Week (Тиждень) (in Ukrainian). 16 September 2015. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- "З'явилися списки фізичних та юридичних осіб РФ, проти яких Україна ввела санкції: Зокрема, у списку фізичних осіб названі 388 прізвищ, у списку юридичних осіб вказані 105 компаній та інших організацій". The Ukrainian Week (Тиждень) (in Ukrainian). 16 September 2015. Archived from the original on 26 June 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- "Додаток 1 до рішення Ради національної безпеки і оборони України від 2 вересня 2015 року: спеціальних економічних та інших обмежувальних заходів (санкцій)" [Appendix 1 to decision for the sake of national security and defense of Ukraine from 2 September 2015: Special economic and other restrictive measures (Sanctions)] (PDF). Presidential decree (in Ukrainian). 2 September 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- "Додаток 2 до рішення Ради національної безпеки і оборони України від 2 вересня 2015 року: спеціальних економічних та інших обмежувальних заходів (санкцій)" [Annex 2 to decision for the sake of national security and defense of Ukraine from 2 September 2015: Special economic and other restrictive measures (Sanctions)] (PDF). Presidential decree (in Ukrainian). 2 September 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- "EU sanctions add to Putin's Crimea headache". EUobserver.com. EUobserver. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- "Obama authorizes 'economic embargo' on Russia's Crimea". RT.com. TV-Novosti. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- "Special Economic Measures (Ukraine) Regulations". Canadian Justice Laws Website. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "Australia and sanctions – Consolidated List – Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade". Dfat.gov.au. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Declaration by the High Representative on behalf of the European Union on the alignment of certain third countries with the Council Decision 2014/145/CFSPconcerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine" (PDF). European Union. 11 April 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Visa and MasterCard resume operations in Crimea". RT.com. TV-Novosti. 30 April 2015. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- Treasury Targets Sanctions Evasion Scheme Facilitating Jet Fuel Shipments to Russian Military Forces in Syria

- Sytas, Andrius (12 April 2016). "Lithuania blacklists 46 for their role in Savchenko trial". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- John O’Loughlin & Gerard Toal (28 February 2019). "The Crimea conundrum: legitimacy and public opinion after annexation". Eurasian Geography and Economics. 60: 6–27. doi:10.1080/15387216.2019.1593873.

- "Crimeans back Russian takeover: If they try to take it back, 'I will fight'". 2019.

- "Italy, Hungary say no automatic renewal of Russia sanctions". Reuters. 14 March 2016. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- Gergely Szakacs (15 August 2014). "Europe 'shot itself in foot' with Russia sanctions: Hungary PM". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "Bulgaria says it is suffering from EU sanctions on Russia". Voice of America. 4 December 2014.

- "Zeman appears on Russian TV to blast sanctions". praguepost.com. 17 November 2014. Archived from the original on 11 April 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- "Slovak PM slams sanctions on Russia, threatens to veto new ones Archived 23 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine ". Reuters. 31 August 2014.

- David Reid, Geoff Cutmore (4 October 2017). "Sanctions on Russia don't work, says Hungary's foreign minister". CNBC. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Tsipras: Greece will seek to mend ties between Russia & EU through European institutions". RT. 8 April 2015. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- "Greece's Tsipras meets Putin in Moscow – as it happened". The Guardian. 8 April 2015. Archived from the original on 17 August 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- Pancevski, Bojan (9 November 2014). "Industry urges Merkel to back down on Moscow sanctions – The Sunday Times". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- WSJ Staff (21 October 2014). "Total CEO Christophe de Margerie's Speech About Russian Sanctions". WSJ. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- Reuters Editorial (26 September 2014). "UniCredit says sanctions hurting Europe more than Russia: Czech media". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- Kirschbaum, Erik (16 November 2016). "German economy minister rejects tougher sanctions on Russia". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 April 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- Tanquintic-Misa, Esther (5 January 2015). "More Anti-Russian Sanctions Will Ultimately Cripple Europe – German Vice-Chancellor". ibtimes.com.au. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- "Paolo Gentiloni; dalla Russia alla Libia, per orientarci nelle crisi "la bussola sarà l'interesse nazionale"". L'Huffington Post. 2 December 2014. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- Economics Minister Johann Schneider-Ammann hopes sanctions against Russia will soon come to an end. swissinfo.ch.

- "Siemens to bypass sanctions and work in Crimea". meduza.io. Archived from the original on 15 November 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Marioni, Max (August 2015). "The cost of Russian sanctions on Western economies" (PDF). In Adriel Kasonta (ed.). BOW Group Research Paper: The Sanctions on Russia. Bow Group. pp. 16–31. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- "Germany threatens retaliation if U.S. sanctions harm its firms Archived 24 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine ". Reuters. 16 June 2017.

- "The U.S. Sanctions Russia, Europe Says 'Ouch!' Archived 16 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine ". Bloomberg. 16 June 2017.

- "US bill on Russia sanctions prompts German, Austrian outcry Archived 19 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine ". Deutsche Welle. 15 June 2017.

- "Germany, Austria Slam US Sanctions Against Russia Archived 30 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine ". U.S. News. 15 June 2017.

- "Germany and Austria warn US over expanded Russia sanctions Archived 15 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine ". Politico. 15 June 2017.

- "Kubicki: "Heute bin ich sittlich und moralisch gefestigt"". Augsburger Allgemeine (in German). 1 May 2018. Archived from the original on 5 May 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Comencini, Vito (6 February 2019). "Vito Comencini: Position The West to Russia seems to me wrong and prejudiced". Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- "France Hopes To See Russia Sanctions Lifted 'This Summer': French Economy Minister". NDTV.com. 24 January 2016. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "French Senate Urges Government To Lift Sanctions on Russia". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 9 June 2016. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- Norman, Laurence (11 September 2016). EU Extends Sanctions on Russian Officials Over Ukraine Crisis. Archived 22 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved: 5 October 2016.

- EU Extends Sanctions on Russian Officials Over Ukraine Crisis. Archived 13 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Washington Post. Retrieved: 13 March 2016.

- Dreyfuss, Bob (19 April 2018). "What the FBI Raid on Michael Cohen Means for the Russia Investigation". The Nation. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Barigazzi, Jacopo (19 June 2017). "EU extends sanctions over Russia's Crimea annexation". Politico. Archived from the original on 19 June 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- "Russia tests Council of Europe in push to regain vote". Financial Times. 26 November 2017. Archived from the original on 27 November 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- France-Presse, Agence. "Council of Europe Postpones Vote on Russia Return". VOA. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "Italy PM says is working to try to end sanctions against Russia". Reuters. 9 March 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Lally, Kathy; Englund, Will (6 December 2012). "Russia fumes as U.S. Senate passes Magnitsky law aimed at human rights". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- "The US Global Magnitsky Act: Questions and Answers". Human Rights Watch. 13 September 2017. Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- Lee, Carol E.; Sonne, Paul (30 December 2016). "U.S. Sanctions Russia Over Election Hacking; Moscow Threatens to Retaliate". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- Barack Obama (29 December 2016). "Statement by the President on Actions in Response to Russian Malicious Cyber Activity and Harassment". obamawhitehouse.archives.gov. White House Office of the Press Secretary. Archived from the original on 27 March 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- "FACT SHEET: Actions in Response to Russian Malicious Cyber Activity and Harassment". White House. 29 December 2016. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- Miles Parks (5 December 2017). "The 10 Events You Need To Know To Understand The Michael Flynn Story". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Lardner, Richard (12 June 2017). "Senate GOP, Dems agree on new sanctions on Russia". ABC News. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- Flegenheimer, Matt (13 June 2017). "New Bipartisan Sanctions Would Punish Russia for Election Meddling". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- "Russia reacts angrily as EU adds 6 companies to sanctions list". Politico. 8 January 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- Sheth, Sonam (15 March 2018). "Trump administration announces new sanctions on Russians charged in the Mueller investigation". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Stephen Collinson; Zachary Cohen. "US punishes Russia but Trump hedges bets on Putin". CNN. Archived from the original on 11 April 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- Calia, Amanda Macias, Mike (6 April 2018). "US sanctions several Russians, including oligarch linked to former Trump campaign chief Paul Manafort". CNBC. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- The 3 biggest names on the latest Russia sanctions list have all popped up in the investigation surrounding Trump

- "Ukraine-/Russia-related Designations and Identification Update". United States Department of the Treasury. 6 April 2018. Archived from the original on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- "US to impose sanctions against Russia over Salisbury nerve agent attack". The Guardian. 6 April 2018. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- Industry and Security Bureau (26 September 2018). "Addition of Certain Entities to the Entity List, Revision of an Entry on the Entity List and Removal of an Entity From the Entity List". Federal Register. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- "Treasury Sanctions Russia over Continued Aggression in Ukraine". U.S. Department of the Treasury. 15 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- "Second Round of Chemical and Biological Weapons Control and Warfare Elimination Act Sanctions on Russia". U.S Department of State. 2 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Ukraine-/Russia-related Designations; Syria Designation".

- "U.S. Sanctions 2 Russians Connected to 'Kremlin Troll Factory'". U.S. Department of the Treasury. 30 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Golubkova, Katya; Baczynska, Gabriela (10 December 2014). "Rouble fall, sanctions hurt Russia's economy: Medvedev". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- Christie, Edward (2015). "Sanctions after Crimea: Have they worked?". NATO Review. NATO. Archived from the original on 12 August 2015.

- "Russian agriculture sector flourishes amid sanctions". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- "German businesses suffer fallout as Russia sanctions bite". Financial Times. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "EU agro-business suffers from Russian Embargo Archived 9 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine ". New Europe. 22 June 2015.

- "Russia Sanctions Stall Europe's Business Aviation Market Archived 6 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine ". Aviation Week. 5 May 2015.

- "Tractors roll into Helsinki for massive farmers' demo". Yle Uutiset. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "Here's What Exxon Lost From Russia Sanctions Archived 29 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine ". Forbes. 27 February 2015.

- "Report of the Special Rapporteur on the negative impact of unilateral coercive measures on the enjoyment of human rights, on his mission to the Russian Federation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- "Unilateral sanctions against Russia hurt most vulnerable groups with limited impact on international businesses, UN expert finds". OHCHR. 28 April 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- "Visit of the Special Rapporteur on the negative impact of unilateral coercive measures on the enjoyment of human rights to the Russian Federation, 24 to 28 April 2017". Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- Sanctions tit-for-tat: Moscow strikes back against US officials Archived 1 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine RT

- Steven Chase (24 March 2014). "Russia imposes sanctions on 13 Canadians, including MPs". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- Putin bans agricultural imports from sanctioning countries for 1 year Archived 7 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine RT, 6 August 2014.

- "Western food imports off the menu as Russia hits back over Ukraine sanctions". The Guardian. 7 August 2014. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- "Указ Президента РФ от 6 августа 2014 г. N 560 "О применении отдельных специальных экономических мер в целях обеспечения безопасности Российской Федерации"" [Presidential Decree of 6 August 2014 N 560 'On the application of certain special economic measures to ensure the security of the Russian Federation']. garant.ru (in Russian). 7 August 2014. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "О мерах по реализации Указа Президента России "О применении отдельных специальных экономических мер в целях обеспечения безопасности Российской Федерации"" [On measures to implement the Decree of the President of Russia "On the application of certain special economic measures in order to ensure the security of the Russian Federation"]. government.ru (in Russian). 7 August 2014. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "Russia hits West with food import ban in sanctions row". BBC News. 7 August 2014. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Payton, Laura (7 August 2014). "Russia sanctions: Vladimir Putin retaliates, sanctions Canada". CBC News.

- "Russia threatens to go beyond food sanctions". Financial Times. 7 August 2014. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Rettman, Andrew (23 January 2015). "Russia suspends official EU parliament visits". Euobserver. Archived from the original on 1 February 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- "Russia bars two EU politicians from Nemtsov funeral". Reuters. 3 March 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- "Russia releases 89-name EU travel blacklist". Yahoo News. Agence France-Presse. 29 May 2015. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- "Eight Swedes on Russia's blacklist". Radio Sweden. 29 May 2015. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- "Russische "Visasperrliste" vom RAM am 27.5. an EU-Delegation Moskau übergeben" [Russian visa bans] (PDF) (in German). Yle. 26 May 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- "European Union anger at Russian travel blacklist". BBC News. 30 May 2015. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Khomami, Nadia (31 May 2015). "Russian entry ban on politicians shows EU sanctions are working, says Rifkind". The Guardian. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 31 May 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- Granlund, John; Eriksson, Niklas (29 May 2015). "Gunnar Hökmark: En rädd regim gör så här" (in Swedish). Aftonbladet. Archived from the original on 1 June 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- Fox, Emily (31 May 2015). "EU reacts with FURY over Russia's 'blacklist' as MP claims Putin sanctions ARE working". express.co.uk. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 1 June 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- Путин подписал указ о продлении контрсанкций Archived 16 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine TASS, 29 June 2016.

- Pospieszna, Paulina; Skrzypczyńska, Joanna; Stępień, Beata (2020). "Hitting Two Birds with One Stone: How Russian Countersanctions Intertwined Political and Economic Goals". PS: Political Science & Politics. 53 (2): 243–247. doi:10.1017/S1049096519001781. ISSN 1049-0965.

Further reading

- Bond, Ian, Christian Odendahl and J. Rankin. "Frozen: The politics and economics of sanctions against Russia." Sentre for European Reform (2015). online

- Gilligan, Emma. "Smart Sanctions against Russia: Human Rights, Magnitsky and the Ukrainian Crisis." Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 24.2 (2016): 257–277. online

- Wang, Wan. "Impact of western sanctions on Russia in the Ukraine crisis." Journal of Politics & Law 8 (2015): 1+ online.

External links

- Ukrainian crisis: sanctions and reactions, Information Telegraph Agency of Russia (owned by the Government of Russia)

- Ukraine and Russia Sanctions, United States Department of State

- EU sanctions against Russia over Ukraine crisis, European Union

- Overview of the European Council policy on sanctions, European Council (European Union)