Russian language in Ukraine

The Russian language is the most common first language in the Donbass and Crimea regions of Ukraine, and the predominant language in large cities in the east and south of the country.[1] The usage and status of the language (as of 2019 Ukrainian is the only state language of Ukraine[2]) is the subject of political disputes within Ukrainian society. Nevertheless, Russian is a widely used language in Ukraine in pop culture and in informal and business communication.[1]

History of Russian language in Ukraine

The East Slavic languages originated in the language spoken in Rus in the medieval period. Significant differences in spoken language in different regions began to be noticed after the division of the Rus lands between the Golden Horde (from about 1240) and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The Lithuanian state eventually allied with the Kingdom of Poland in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth of 1569-1795. Muscovites under the Golden Horde developed what became the modern Russian language; people in the northern Lithuanian sector developed Belorussian, and in the southern (Polish) sector Ukrainian.

Note that the ethnonym Ukrainian for the southern eastern Slavic people did not become well-established until the 19th century, although English-speakers (for example) called those peoples' land Ukraine in English from before the 18th century. The area was generally known in the West as "Ruthenia", and the people as "Ruthenians" (The Oxford English Dictionary traces the word "Ukrainian" in English back as far as 1804, and records its application to the Ukrainian language from 1886[3]). The Russian imperial centre, however, preferred the names "Little" and "White" Russias for the Ukrainian and Belarusian lands respectively, as distinct from Great Russia.

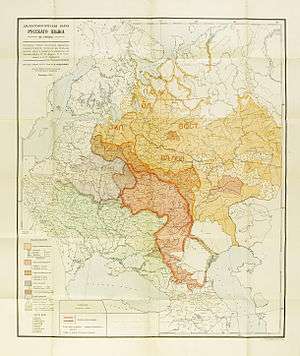

No definitive geographical border separated people speaking Russian and those speaking Ukrainian - rather gradual shifts in vocabulary and pronunciation marked the areas between the historical cores of the languages. Since the 20th century, however, people have started to identify themselves with their spoken vernacular and to conform to the literary norms set by academics.

Although the ancestors of a small ethnic group of Russians - Goriuns resided in the Putyvl region (in present-day northern Ukraine) in the times of Grand Duchy of Lithuania or perhaps even earlier,[4][5] the Russian language in Ukraine has primarily come to exist in that country through two channels: through the migration of ethnic Russians into Ukraine and through the adoption of the Russian language by Ukrainians.

Russian settlers

The first new waves of Russian settlers onto what is now Ukrainian territory came in the late-16th century to the empty lands of Slobozhanshchyna (in the region of Kharkiv) that Russia gained from the Tatars,[5] although Ukrainian peasants from the west escaping harsh exploitative conditions outnumbered them.[6]

More Russian speakers appeared in the northern, central and eastern territories of modern Ukraine during the late 17th century, following the Cossack Rebellion (1648–1657) which Bohdan Khmelnytsky led against Poland. The Khmelnytsky Uprising led to a massive movement of Ukrainian settlers to the Slobozhanshchyna region, which converted it from a sparsely inhabited frontier area to one of the major populated regions of the Tsardom of Russia. Following the Pereyaslav Rada of 1654 the modern northern and eastern parts of Ukraine came under the hegemony of the Russian Tsardom. This brought the first significant, but still small, wave of Russian settlers into central Ukraine (primarily several thousand soldiers stationed in garrisons,[6] out of a population of approximately 1.2 million[7] non-Russians). Although the number of Russian settlers in Ukraine prior to the 18th century remained small, the local upper-classes within the part of Ukraine acquired by Russia came to use the Russian language widely.

Beginning in the late 18th century, large numbers of Russians settled in newly-acquired lands in what is now southern Ukraine, a region then known as Novorossiya ("New Russia"). These lands - previously known as the Wild Fields - had been largely empty prior to the 18th century due to the threat of Crimean Tatar raids, but once St Petersburg had eliminated the Tatar state as a threat, Russian nobles were granted large tracts of fertile land for working by newly-arrived peasants, most of them ethnic Ukrainians but many of them Russians.[8]

Dramatic increase of Russian settlers

The 19th century saw a dramatic increase in the urban Russian population in present-day Ukraine, as ethnic Russian settlers moved into and populated the newly industrialised and growing towns. At the beginning of the 20th century the Russians formed the largest ethnic group in almost all large cities within Ukraine's modern borders, including Kiev (54.2%), Kharkiv (63.1%), Odessa (49.09%), Mykolaiv (66.33%), Mariupol (63.22%), Luhansk, (68.16%), Kherson (47.21%), Melitopol (42.8%), Ekaterinoslav, (41.78%), Kropyvnytskyi (34.64%), Simferopol (45.64%), Yalta (66.17%), Kerch (57.8%), Sevastopol (63.46%).[9] The Ukrainian migrants who settled in these cities entered a Russian-speaking milieu (particularly with Russian-speaking administration) and needed to adopt the Russian language.

Suppression and fostering of the Ukrainian language

The Russian Empire promoted the spread of the Russian language among the native Ukrainian population, actively refusing to acknowledge the existence of a Ukrainian language.

Alarmed by the threat of Ukrainian separatism (in its turn influenced by the 1863 demands of Polish nationalists), the Russian Minister of Internal Affairs Pyotr Valuev in 1863 issued a secret decree that banned the publication of religious texts and educational texts written in the Ukrainian language[10] as non-grammatical, but allowed all other texts, including fiction. The Emperor Alexander II in 1876 expanded this ban by issuing the Ems Ukaz (which lapsed in 1905). The Ukaz banned all Ukrainian-language books and song-lyrics, as well as the importation of such works. Furthermore, Ukrainian-language public performances, plays, and lectures were forbidden.[11] In 1881 the decree was amended to allow the publishing of lyrics and dictionaries, and the performances of some plays in the Ukrainian language with local officials' approval. Ukrainian-only troupes were, however, forbidden. Approximately 9% of the population spoke Russian at the time of the Russian Empire Census of 1897. as opposed to 44.31% of the total population of the Empire.[12]

In 1918 the Soviet Council of People's Commissars decreed that nationalities under their control had the right to education in their own language.[13] Thus Ukrainians in the Soviet era were entitled to study and learn in the Ukrainian language. During the Soviet times, the attitude to Ukrainian language and culture went through periods of promotion (policy of "korenization", c. 1923 to c. 1933), suppression (during the subsequent period of Stalinism), and renewed Ukrainization (notably in the epoch of Khrushchev, c. 1953 to 1964). Ukrainian cultural organizations, such as theatres or the Writers' Union, were funded by the central administration. While officially there was no state language in the Soviet Union until 1990, Russian in practice had an implicitly privileged position as the only language widely spoken across the country. In 1990 Russian became legally the official all-Union language of the Soviet Union, with constituent republics having rights to declare their own official languages.[14][15] The Ukrainian language, despite official encouragement and government funding, like other regional languages, was often frowned upon or quietly discouraged, which led to a gradual decline in its usage.[16]

Ukrainization in modern Ukraine

Since the Euromaidan of 2013-2014, the Ukrainian government has issued several laws aimed at encouraging Ukrainization in the media, in education and in other spheres.

In February 2017, the Ukrainian government banned the commercial importation of books from Russia, which had accounted for up to 60% of all titles sold in Ukraine.[17]

On May 23, 2017, the Ukrainian parliament approved the law that most broadcast content should be in Ukrainian (75% of national carriers and 50% of local carriers).

The 2017 law on education provides that Ukrainian language is the language of education at all levels except for one or more subjects that are allowed to be taught in two or more languages, namely English or one of the other official languages of the European Union (i.e., excluding Russian).[18] The law does state that persons belonging to the indigenous peoples of Ukraine are guaranteed the right to study at public pre-school institutes and primary schools in "the language of instruction of the respective indigenous people, along with the state language of instruction" in separate classes or groups.[18] The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) has expressed concern with this measure and with the lack of "real consultation" with the representatives of national minorities.[19] In July 2018, The Mykolaiv Okrug Administrative Court liquidated the status of Russian as a regional language, on the suit (bringing to the norms of the national legislation due to the recognition of the law "On the principles of the state language policy" by the Constitutional Court of Ukraine as unconstitutional) of the First Deputy Prosecutor of the Mykolaiv Oblast.[20] In October and December 2018, parliaments of the city of Kherson and of Kharkiv Oblast also abolished the status of the Russian language as a regional one.[21]

Current usage statistics

(according to 2001 census)

There is a large difference between the numbers of people whose native language is Russian and people who adopted Russian as their everyday communication language. Another thing to keep in mind is that the percentage of Russian-speaking citizens is significantly higher in cities than in rural areas across the whole country.

2001 Census

According to official data from the 2001 Ukrainian census, the Russian language is native for 29.6% of Ukraine's population (about 14.3 million people).[22] Ethnic Russians form 56% of the total Russian-native-language population, while the remainder are people of other ethnic background: 5,545,000 Ukrainians, 172,000 Belarusians, 86,000 Jews, 81,000 Greeks, 62,000 Bulgarians, 46,000 Moldovans, 43,000 Tatars, 43,000 Armenians, 22,000 Poles, 21,000 Germans, 15,000 Crimean Tatars.

Therefore, the Russian-speaking population in Ukraine forms the largest linguistic group in modern Europe with its language being non-official in the state. The Russian-speaking population of Ukraine constitutes the largest Russophone community outside the Russian Federation.

Polls

According to July 2012 polling by RATING, 50% of the surveyed adult residents over 18 years of age considered their native language to be Ukrainian, 29% said Russian, 20% identified both Russian and Ukrainian as their native language, 1% gave another language.[23] 5% could not decide which language is their native one.[23] Almost 80% of respondents stated they did not have any problems using their native language in 2011.[23] 8% stated they had experienced difficulty in the execution (understanding) of official documents; mostly middle-aged and elderly people in South Ukraine and the Donets Basin.[23]

According to a 2004 public opinion poll by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, the number of people using Russian language in their homes considerably exceeds the number of those who declared Russian as their native language in the census. According to the survey, Russian is used at home by 43–46% of the population of the country (in other words a similar proportion to Ukrainian) and Russophones make a majority of the population in Eastern and Southern regions of Ukraine:[24]

- Autonomous Republic of Crimea — 97% of the population

- Dnipropetrovsk Oblast — 72%

- Donetsk Oblast — 93%

- Luhansk Oblast — 89%

- Zaporizhia Oblast — 81%

- Odessa Oblast — 85%

- Kharkiv Oblast — 74%

- Mykolaiv Oblast — 66%

Russian language dominates in informal communication in the capital of Ukraine, Kiev.[25][26] It is also used by a sizeable linguistic minority (4-5% of the total population) in Central and Western Ukraine.[27] 83% of Ukrainians responding to a 2008 Gallup poll preferred to use Russian instead of Ukrainian to take the survey.[28]

According to data obtained by the "Public opinion" foundation (2002), the population of the oblast centres prefers to use Russian (75%).[29] Continuous Russian linguistic areas occupy certain regions of Crimea, Donbass, Slobozhanshchyna, southern parts of Odessa and Zaporizhia oblasts, while Russian linguistic enclaves exist in central and northern Ukraine.

| 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russian language | 34.7 | 37.8 | 36.1 | 35.1 | 36.5 | 36.1 | 35.1 | 38.1 | 34.5 | 38.1 | 35.7 | 34.1 |

| 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mainly Russian | 32.4 | 32.8 | 33.1 | 34.5 | 33.4 | 33.6 | 36.0 | 36.7 | 33.2 | 36.0 | 34.3 | 36.4 |

| Both Russian and Ukrainian | 29.4 | 34.5 | 29.6 | 26.8 | 28.4 | 29.0 | 24.8 | 25.8 | 28.0 | 25.2 | 26.3 | 21.6 |

Russian language in Ukrainian politics

The Russian language in Ukraine is recognized as the language of a national minority but not as a state language. It is explicitly mentioned in the Constitution of Ukraine adopted by the parliament in 1996. Article 10 of the Constitution reads: "In Ukraine, the free development, use and protection of Russian, and other languages of national minorities of Ukraine, is guaranteed".[31] The Constitution declares Ukrainian language as the state language of the country, while other languages spoken in Ukraine are guaranteed constitutional protection. The Ukrainian language was adopted as the state language by the Law on Languages adopted in Ukrainian SSR in 1989; Russian was specified as the language of communication with the other republics of Soviet Union.[32] Ukraine signed the European Charter on Regional or Minority Languages in 1996, but ratified it only in 2002 when the Parliament adopted the law that partly implemented the charter.[33]

The issue of Russian receiving the status of second official language has been the subject of extended controversial discussion ever since Ukraine became independent in 1991. In every Ukrainian election, many politicians, such as former president Leonid Kuchma, used their promise of making Russian a second state language to win support. The recent President of Ukraine, Viktor Yanukovych continued this practice when he was opposition leader. But in an interview with Kommersant, during the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election-campaign, he stated that the status of Russian in Ukraine "is too politicized" and said that if elected President in 2010, he would "have a real opportunity to adopt a law on languages, which implements the requirements of the European Charter of regional languages". He implied these law would need 226 votes in the Ukrainian parliament (50% of the votes instead of the 75% of the votes needed to change the constitution of Ukraine).[34] After his early 2010 election as President, Yanukovych stated (on March 9, 2010) "Ukraine will continue to promote the Ukrainian language as its only state language".[35] At the same time, he stressed that it also necessary to develop other regional languages.[36]

In 1994, a referendum took place in the Donetsk Oblast and the Luhansk Oblast, with around 90% supporting the Russian language gaining status of an official language alongside Ukrainian, and for the Russian language to be an official language on a regional level; however, the referendum was annulled by the (central) Ukrainian government.[37][38]

Former president Viktor Yushchenko, during his 2004 Presidential campaign, also claimed a willingness to introduce more equality for Russian speakers. His clipping service spread an announcement of his promise to make Russian language proficiency obligatory for officials who interact with Russian-speaking citizens.[39] In 2005 Yushchenko stated that he had never signed this decree project.[40] The controversy was seen by some as a deliberate policy of Ukrainization.[41][42]

In 2006, the Kharkiv City Rada was the first to declare Russian to be a regional language.[43] Following that, almost all southern and eastern oblasts (Luhansk, Donetsk, Mykolaiv, Kharkiv, Zaporizhia, and Kherson oblasts), and many major southern and eastern cities (Sevastopol, Dnipropetrovsk, Donetsk, Yalta, Luhansk, Zaporizhia, Kryvyi Rih, Odessa) followed suit. Several courts overturned the decision to change the status of the Russian language in the cities of Kryvyi Rih, Kherson, Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhia and Mykolaiv while in Donetsk, Mykolaiv and Kharkiv oblasts it was retained.[44]

In August 2012, a law on regional languages entitled any local language spoken by at least a 10% minority to be declared official within that area.[45] Russian was within weeks declared as a regional language in several southern and eastern oblasts and cities.[46] On 23 February 2014, a bill repealing the law was approved by 232 deputies out of 450[47] but not signed into law by acting-president Oleksandr Turchynov.[48] On 28 February 2018, the Constitutional Court of Ukraine ruled this legislation unconstitutional.[49]

In December 2016, the importation of "anti-Ukrainian" books from Russia was restricted. In February 2017 the Ukrainian government completely banned the commercial importation of books from Russia, which had accounted for up to 60% of all titles sold.[50]

The recent election to presidency of Volodymyr (Vladimir) Zelenskiy in April 2019, himself the product of a Russian-speaking family in Krivoy Rog, could signal both a greater acceptance of the role of Russian language in Ukraine and a decrease in the (perceived) anti-Russian Ukrainization policies issuing from the Maidan revolution of 2014 and the subsequent presidential administration of Petro Poroshenko (though raised as a Russian speaker himself). While Zelenskiy made the official announcement of his candidacy in fluent Ukrainian, the language of his famous comedy shows (e.g., Studio Kvartal 95) was Russian.

Surveys on the status of the Russian language

| 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 52.0 | 50.9 | 43.9 | 47.6 | 46.7 | 44.0 | 47.4 | 48.6 | 47.3 | 47.5 | 48.6 |

| Hard to say | 15.3 | 16.1 | 20.6 | 15.3 | 18.1 | 19.3 | 16.2 | 20.0 | 20.4 | 20.0 | 16.8 |

| No | 32.6 | 32.9 | 35.5 | 37.0 | 35.1 | 36.2 | 36.0 | 31.1 | 31.9 | 32.2 | 34.4 |

| No answer | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

According to a survey by the Research and Branding Group (June 2006), the majority of respondents supported the decisions of local authorities: 52% largely supported (including 69% of population of eastern oblasts and 56% of southern regions), 34% largely did not support the decisions, 9% - answered "partially support and partially not", 5% had no opinion.[51] According to an all-Ukrainian poll carried out in February 2008 by "Ukrainian Democratic Circle" 15% of those polled said that the language issue should be immediately solved,[52] in November 2009 this was 14.7%; in the November 2009 poll 35.8% wanted both the Russian and Ukrainian language to be state languages.[53]

According to polling by RATING, the level of support for granting Russian the status of a state language decreased (from 54% to 46%) and the number of opponents increased (from 40% to 45%) between 2009 and May 2012;[23] in July 2012 41% of respondents supported granting Russian the status of a state language and 51% opposed it.[23] (In July 2012) among the biggest supporters of bilingualism were residents of the Donets Basin (85%), South Ukraine (72%) and East Ukraine (50%).[23] A further poll conducted by RATING in September–October 2012 found 51% opposed granting official status to the Russian language, whereas 41% supported it. The largest regions of support were Donbass (75%), southern (72%) and eastern (53%), whereas nearly 70% of northern and central Ukraine, and 90% of western Ukraine were in opposition.[54] A survey conducted in February 2015 by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology found that support for Russian as a state language had dropped to 19% (37% in the south, 31% in Donbass and other eastern oblasts).[55] 52% (West: 44%, Central: 57%; South: 43%; East: 61%) said that Russian should be official only in regions where the majority wanted it and 21% said it should be removed from official use.[55]

Other surveys

Although officially Russian speakers comprise about 30% (2001 census), 39% of Ukrainians interviewed in a 2006 survey believed that the rights of Russophones were violated[56] because the Russian language is not official in the country, whereas 38% had the opposite position.[57][58]

A cross-national survey found that 0.5% of respondents felt they were discriminated against because of their language.[59] According to a poll carried out by the Social Research Center at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy in late 2009 ideological issues were ranked third (15%) as reasons to organize mass protest actions (in particular, the issues of joining NATO, the status of the Russian language, the activities of left- and right-wing political groups, etc.); behind economic issues (25%) and problems of ownership (17%).[60] According to a March 2010 survey, forced Ukrainization and Russian language suppression are of concern to 4.8% of the population.[61]

Use of Russian in specific spheres

Russian literature in Ukraine

Historically, many famous writers of Russian literature were born and lived in Ukraine. Nikolai Gogol is probably the most famous example of shared Russo-Ukrainian heritage: Ukrainian by descent, he wrote in Russian, and significantly contributed to culture of both nations. Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov was born in Kiev, as well as poet Ilya Erenburg. A number of notable Russian writers and poets hailed from Odessa, including Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov, Anna Akhmatova, Isaak Babel. Russian child poet Nika Turbina was born in Yalta, Crimea.

A significant number of contemporary authors from Ukraine write in Russian.[63] This is especially notable within science fiction and fantasy genres.[63] Kharkiv is considered the "capital city" of Ukrainian sci-fi and fantasy, it is home to several popular Russophone Ukrainian writers, such as H. L. Oldie (pen name for Oleg Ladyzhensky and Dmitry Gromov),[64] Alexander Zorich,[65] Andrei Valentinov, and Yuri Nikitin. Science fiction convention Zvezdny Most (Rus. for "Star Bridge") is held in Kharkiv annually. Russophone Ukrainian writers also hail from Kiev, those include Marina and Sergey Dyachenko[66] and Vladimir Arenev. Max Frei hails from Odessa, and Vera Kamsha was born in Lviv. Other Russophone Ukrainian writers of sci-fi and fantasy include Vladimir Vasilyev, Vladislav Rusanov, Alexander Mazin and Fyodor Berezin. RBG-Azimuth, Ukraine's largest sci-fi and fantasy magazine, is published in Russian, as well as now defunct Realnost Fantastiki.[67]

Outside science fiction and fantasy, there is also a number of Russophone realist writers and poets. Ukrainian literary magazine Sho listed Alexander Kabanov, Boris Khersonsky, Andrey Polyakov, Andrey Kurkov and Vladimir Rafeyenko as best Russophone Ukrainian writers of 2013.[68]

According to H. L. Oldie, writing in Russian is an easier way for Ukrainian authors to be published and reach a broader audience. The authors say that it is because of Ukraine's ineffective book publishing policy: while Russian publishers are interested in popular literature, Ukrainian publishers rely mostly on grant givers.[63] Many Ukrainian publishers agree and complain about low demand and low profitability for books in Ukrainian, compared to books in Russian.[69]

In the media

A 2012 study showed that:[70]

- on the radio, 3.4% of songs were in Ukrainian while 60% were in Russian

- over 60% of newspapers, 83% of journals and 87% of books were in Russian

- 28% of TV programs were in Ukrainian, even on state-owned channels

Russian-language programming is sometimes subtitled in Ukrainian, and commercials during Russian-language programs are in Ukrainian on Ukraine-based media.

On March 11, 2014, amidst pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine, the Ukrainian National Council on Television and Radio Broadcasting shut down the broadcast of Russian television channels Rossiya 24, Channel One Russia, RTR Planeta, and NTV Mir in Ukraine.[71][72] Since 19 August 2014 Ukraine has blocked 14 Russian television channels "to protect its media space from aggression from Russia, which has been deliberately inciting hatred and discord among Ukrainian citizens".[73]

In early June 2015 162 Russian movies and TV series were banned in Ukraine because they were seen to contains popularization, agitation and/or propaganda for the 2014–15 Russian military intervention in Ukraine (this military intervention is denied by Russia).[74][75] All movies that feature "unwanted" Russian or Russia-supporting actors were also banned.[76]

On the Internet

Russian is by far the preferred language on websites in Ukraine (80.1%), followed by English (10.1%), then Ukrainian (9.5%). The Russian language version of Wikipedia is five times more popular within Ukraine than the Ukrainian one, with these numbers matching those for the 2008 Gallup poll cited above (in which 83% of Ukrainians preferred to take the survey in Russian and 17% in Ukrainian.)[77]

While government organizations are required to have their websites in Ukrainian, Ukrainian usage of the Internet is mostly in the Russian language. According to DomainTyper, the top ranking .ua domains are google.com.ua, yandex.ua, ex.ua and i.ua, all of which use the Russian language as default.[78] According to 2013 UIA research, four of the five most popular websites (aside from Google) in Ukraine were Russian or Russophone: those are Vkontakte, Mail.ru, Yandex, and Odnoklassniki.[79] The top Ukrainian language website in this rank is Ukr.net, which was only the 8th most popular, and even Ukr.net uses both languages interchangeably.

On May 15, 2017, Ukrainian president Poroshenko issued a decree than demanded all Ukrainian internet providers to block access to all most popular Russian social media and websites, including VK, Odnoklassniki, Mail.ru, Yandex citing matters of national security in the context of War in Donbass and explaining it as a response to "massive Russian cyberattacks across the world".[80][81] On the following day the demand for applications that allowed to access blocked websites skyrocketed in Ukrainian segments of App Store and Google Play.[82] The ban was condemned by Human Rights Watch that called it "a cynical, politically expedient attack on the right to information affecting millions of Ukrainians, and their personal and professional lives",[83] while head of Council of Europe[84] expressed a "strong concern" about the ban.

In education

Among private secondary schools, each individual institution decides whether to study Russian or not.[85] All Russian-language schools teach the Ukrainian language as a required course.[86]

The number of Russian-teaching schools has reduced since Ukrainian independence in 1991 and now it is much lower than the proportion of Russophones,[87][88][89] but still higher than the proportion of ethnic Russians.

The Law on Education formerly granted Ukrainian families (parents and their children) a right to choose their native language for schools and studies.[90] This was changed by a new law in 2017 that only allows the use of Ukrainian in secondary schools and higher.

Higher education institutions in Ukraine generally use Ukrainian as the language of instruction.[1]

According to parliamentarians of the Supreme Council of Crimea, in 2010 90% students of Crimea were studying in Russian language schools.[91] At the same time, only 7% of students in Crimea study in Ukrainian language schools.[92] In 2012, the only Ukrainian boarding school (50 pupils) in Sevastopol was closed, while children who would not study in Russian language were to be transferred to a boarding school for children with retarded development (see Intellectual disability).[93]

In courts

Since 1 January 2010, court proceedings have been allowed to take place in Russian on mutual consent of parties. Citizens who are unable to speak Ukrainian or Russian are allowed to use their native language or the services of an interpreter.[94]

In business

As of 2008, business affairs in Ukraine were mainly dealt with in Russian,[1] Advanced technical and engineering courses at the university level in Ukraine were taught in Russian, which is about to be changed according to the 2017 law "On Education".

See also

- Russians in Ukraine

- Human Rights Public Movement "Russian-speaking Ukraine", a non-governmental organisation based in Ukraine.

- Surzhyk

- Russian book ban in Ukraine

Bibliography

- Русские говоры Сумской области. Сумы, 1998. — 160 с ISBN 966-7413-01-2

- Русские говоры на Украине. Киев: Наукова думка, 1982. — 231 с.

- Степанов, Є. М.: Російське мовлення Одеси: Монографія. За редакцією д-ра філол. наук, проф. Ю. О. Карпенка, Одеський національний університет ім. І. І. Мечнікова. Одеса: Астропринт, 2004. — 494 с.

- Фомин А. И. Языковой вопрос в Украине: идеология, право, политика. Монография. Второе издание, дополненное. — Киев: Журнал «Радуга». — 264 с ISBN 966-8325-65-6

- Rebounding Identities: The Politics of Identity in Russia and Ukraine. Edited by Dominique Arel and Blair A. Ruble Copub. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. 384 pages. ISBN 0-8018-8562-0 and ISBN 978-0-8018-8562-4

- Bilaniuk, Laada. Contested Tongues: Language Politics And Cultural Correction in Ukraine. Cornell University Press, 2005. 256 pages. ISBN 978-0-8014-4349-7

- Laitin, David Dennis. Identity in Formation: The Russian-Speaking Populations in the Near Abroad. Cornell University Press, 1998. 417 pages. ISBN 0-8014-8495-2

References

- Bilaniuk, Laada; Svitlana Melnyk (2008). "A Tense and Shifting Balance: Bilingualism and Education in Ukraine". In Aneta Pavlenko (ed.). Multilingualism in Post-Soviet Countries. Multilingual Matters. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-84769-087-6.

-

"About Ukraine - MFA of Ukraine". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

About Ukraine [:] Official language: Ukrainian

- "Ukrainian". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- F.D. Klimchuk, About ethnolinguistic history of Left Bank of Dnieper (in connection to the ethnogenesis of Goriuns). Published in "Goriuns: history, language, culture", Proceedings of International Scientific Conference, (Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences, February 13, 2004)

- "Russians in Ukraine". Archived from the original on May 19, 2007. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- "Slobidska Ukraine". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Subtelny, Orest (December 28, 2017). "Ukraine: A History". University of Toronto Press. Retrieved December 28, 2017 – via Google Books.

- "Ukraine - History, Geography, People, & Language". britannica.com.

- Дністрянський М.С. Етнополітична географія України. Лівів Літопис, видавництво ЛНУ імені Івана Франка, 2006, page 342 ISBN 966-7007-60-X

- Miller, Alexei (203). The Ukrainian Question. The Russian Empire and Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century. Budapest-New York: Central European University Press. ISBN 963-9241-60-1.

- Magoscy, R. (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Распределение населения по родному языку, губерниям и областям (in Russian). Demoscope Weekly. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

-

Anderson, Barbara A.; Silver, Brian D. (2018) [1992]. "Equality, Efficiency, and Politics in Soviet Bilingual Education Policy, 1934-1980". In Denber, Rachel (ed.). The Soviet Nationality Reader: The Disintegration In Context. New York: Routledge. p. 358. ISBN 9780429964381. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

In 1918 a rule was introduced by the Council of People's Commissars that called for the establishment of native-language schools for national minorities whenever there were at least 25 pupils at a given grade level who spoke that language [...].

- Grenoble, L. A. (July 31, 2003). "Language Policy in the Soviet Union". Springer Science & Business Media. Retrieved December 28, 2017 – via Google Books.

- "СССР. ЗАКОН СССР ОТ 24.04.1990 О ЯЗЫКАХ НАРОДОВ СССР". legal-ussr.narod.ru. Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Grenoble, L. A. (July 31, 2003). "Language Policy in the Soviet Union". Springer Science & Business Media. p. 83. Retrieved December 28, 2017 – via Google Books.

- Kean, Danuta (February 14, 2017). "Ukraine publishers speak out against ban on Russian books". The Guardian. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

Ukrainian publishers have reacted angrily to their government's ban on importing books from Russia, claiming it will create a black market and damage the domestic industry. [...] Books from Russia account for up to 60% of all titles sold in Ukraine and are estimated to make up 100,000 sales a year.

- Про освіту | від 05.09.2017 № 2145-VIII (Сторінка 1 з 7)

- "PACE - Resolution 2189 (2017) - The new Ukrainian law on education: a major impediment to the teaching of national minorities' mother tongues". assembly.coe.int. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

The Parliamentary Assembly is concerned about the articles relating to education in minority languages of the new Education Act adopted on 5 September 2017 by the Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian Parliament) and signed on 27 September 2017 by the Ukrainian President, Petro Poroshenko. [...] The Assembly deplores the fact that there was no real consultation with representatives of national minorities in Ukraine on the new version of Article 7 of the act adopted by the Verkhovna Rada.

- "31.07.2018". Prosecutor's Office of Mykolaiv Oblast (Press release) (in Ukrainian). Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- (in Ukrainian) In the Kharkiv region abolished the regional status of the Russian language - a deputy, Ukrayinska Pravda (13 December 2018).

- "Results / General results of the census". 2001 Ukrainian Census. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- The language question, the results of recent research in 2012, RATING (25 May 2012)

- "Portrait of Yushchenko and Yanukovych electorates". Analitik (in Russian). Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- "Лариса Масенко". www.ji.lviv.ua. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- "Byurkhovetskiy: Klichko - ne sornyak i ne buryan, i emu nuzhno vyrasti". Korrespondent (in Russian). Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- "In Ukraine there are more Russian language speakers than Ukrainian ones". Evraziyskaya panorama (in Russian). Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- Gradirovski, Sergei; Neli Esipova (August 1, 2008). "Russian Language Enjoying a Boost in Post-Soviet States". Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- "Евразийская панорама". www.demoscope.ru. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- "Ukrainian society 1994-2005: sociological monitoring" (PDF). dif.org.ua/ (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on March 13, 2007. Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- Article 10 Archived May 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine of the Constitution says: "The state language of Ukraine is the Ukrainian language. The State ensures the comprehensive development and functioning of the Ukrainian language in all spheres of social life throughout the entire territory of Ukraine. In Ukraine, the free development, use and protection of Russian, and other languages of national minorities of Ukraine, is guaranteed."

- On Languages in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Law. 1989 (in English)

- "В.Колесниченко. "Европейская хартия региональных языков или языков меньшинств. Отчет о ее выполнении в Украине, а также о ситуации с правами языковых меньшинств и проявлениями расизма и нетерпимости"". www.from-ua.com. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- (in Russian) "Доверия к Тимошенко у меня нет и быть не может", Kommersant (December 9, 2009)

- Yanukovych: Ukraine will not have second state language, Kyiv Post (March 9, 2010)

- Янукович: Русский язык не будет вторым государственным , Подробности (March 9, 2010 13:10)

- "Донбасс: забытый референдум-1994". May 12, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- "Киев уже 20 лет обманывает Донбасс: Донецкая и Луганская области еще в 1994 году проголосовали за федерализацию, русский язык и евразийскую интеграцию". Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Clipping service of Viktor Yuschenko (October 18, 2004). "Yuschenko guarantee equal rights for Russian and other minority languages - Decree project". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- Lenta.ru (July 18, 2005). "Yuschenko appealed to Foreign Office to forget Russian language". Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- An interview with Prof. Lara Sinelnikova, Русский язык на Украине – проблема государственной безопасности, Novyi Region, 19.09.06

- Tatyana Krynitsyna, Два языка - один народ, Kharkiv Branch of the Party of Regions, 09.12.2005

- http://pravopys.vlada.kiev.ua/index.php?id=487

- "Russian language in Odessa is acknowledged as the second official government language ..." Newsru.com (in Russian). Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- Yanukovych signs language bill into law. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- Russian spreads like wildfires in dry Ukrainian forest. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- "На Украине отменили закон о региональном статусе русского языка". Lenta.ru. Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- "Ukraine's parliament-appointed acting president says language law to stay effective". ITAR-TASS. March 1, 2014.

- Constitutional Court declares unconstitutional language law of Kivalov-Kolesnichenko, Ukrinform (28 February 2018)

- Kean, Danuta (February 14, 2017). "Ukraine publishers speak out against ban on Russian books". The Guardian. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- "Русскому языку — да, НАТО — нет, — говорят результаты социсследований - Новости". www.ura-inform.com. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- 80% of Ukrainians do not consider language issue a top-priority, UNIAN (23 February 2009)

- Poll: more than half of Ukrainians do not consider language issue pressing, Kyiv Post (November 25, 2009)

- "Poll: Over half of Ukrainians against granting official status to Russian language - Dec. 27, 2012". December 27, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Ставлення до статусу російської мови в Україні [Views on the status of the Russian language in Ukraine]. Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (in Ukrainian). April 10, 2015.

- According to parliamentary deputy Vadym Kolesnichenko, the official policies of the Ukrainian state are discriminatory towards the Russian-speaking population. The Russian speaking population received 12 times less state funding than the tiny Romanian-speaking population in 2005-2006. Education in Russian is nearly nonexistent in all central and western oblasts and Kiev. The Russian language is no longer in higher education in all Ukraine, including areas with a Russian-speaking majority. The broadcasting in Russian averaged 11.6% (TV) and 3.5% (radio) in 2005. Kolesnichenko is a member of Party of Regions with majority of electorate in eastern and south Russian-speaking regions.

- "Большинство украинцев говорят на русском языке". December 4, 2006. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- "Украинцы лучше владеют русским языком, чем украинским: соцопрос". Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Evhen Golovakha, Andriy Gorbachyk, Natalia Panina, "Ukraine and Europe: Outcomes of International Comparative Sociological Survey", Kiev, Institute of Sociology of NAS of Ukraine, 2007, ISBN 978-966-02-4352-1, pp. 133-135 in Section: "9. Social discrimination and migration" (pdf)

- Poll: economic issues and problems of ownership main reasons for public protests, Kyiv Post (December 4, 2009)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 14, 2010. Retrieved April 12, 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "2000 – 2009". May 26, 2013. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Oldie, H.L.; Dyachenko, Marina and Sergey; Valentinov, Andrey (2005). Пять авторов в поисках ответа (послесловие к роману "Пентакль") [Five authors in search for answers (an afterword to Pentacle)] (in Russian). Moscow: Eksmo. ISBN 5-699-09313-3.

Украиноязычная фантастика переживает сейчас не лучшие дни. ... Если же говорить о фантастике, написанной гражданами Украины в целом, независимо от языка (в основном, естественно, на русском), — то здесь картина куда более радужная. В Украине сейчас работают более тридцати активно издающихся писателей-фантастов, у кого регулярно выходят книги (в основном, в России), кто пользуется заслуженной любовью читателей; многие из них являются лауреатами ряда престижных литературных премий, в том числе и международных.

Speculative fiction in Ukrainian is living through a hard time today... Speaking of fiction written by Ukrainian citizens, regardless of language (primarily Russian, of course), there's a brighter picture. More than 30 fantasy and science fiction writers are active here, their books are regularly published (in Russia, mostly), they enjoy the readers' love they deserve; many are recipients of prestigious literary awards, including international. - H. L. Oldie official website: biography (Russian)

- Alexander Zorich biography (English)

- Marina and Sergey Dyachenko: Writers About Themselves (English)

- "Архив фантастики". Archivsf.narod.ru. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- "Писатель, знай свое место - Журнал "Шо"". www.sho.kiev.ua. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Книгоиздание в Украине: мнения экспертов - «Контракты» №25 Июнь 2006г.

- "Українська мова втрачає позиції в освіті та книговиданні, але тримається в кінопрокаті". Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- http://www.kyivpost.com/content/ukraine/half-of-ukraines-providers-stop-broadcasting-russian-television-channels-339047.html

http://en.ria.ru/world/20140311/188326369/Russia-Slams-Violation-of-Media-Freedoms-in-Ukraine.html - Ukraine hits back at Russian TV onslaught, BBC News (12 March 2014)

- Ukraine bans Russian TV channels for airing war 'propaganda', Reuters (19 August 2014)

- (in Ukrainian) Released list of 162 banned Russian movies and TV series, Ukrayinska Pravda (4 June 2015)

- "Moscow Stifles Dissent as Soldiers Return From Ukraine in Coffins". The Moscow Times. Reuters. September 12, 2014. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- The Star.Ukraine bans films featuring blacklisted Russian actors, including Gerard Depardieu. By The Associated Press. Sun., Aug. 9, 2015

- "Ukraine's Ongoing Struggle With Its Russian Identity". www.worldpoliticsreview.com. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- domaintyper. "Most Popular Websites with .UA domain". domaintyper.com. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- UIA names the TOP 25 most visited websites in Ukraine. 21.10.2013

- The Economist. Ukraine bans its top social networks because they are Russian

- The Guardian. Ukraine blocks popular social networks as part of sanctions on Russia Tuesday 16 May 2017 17.40 BST

- Ukrainian users have blocked VPN access on iOS and Android 18.05.2017

- Ukraine: Revoke Ban on Dozens of Russian Web Companies May 16, 2017 11:00PM EDT

- Council of Europe chief alarmed at Kiev's decision to block Russian social networks. May 17, 2017

- "Співпраця України і Російської Федерації у сфері освіти і науки - Острів знань". ostriv.in.ua. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Ukraine Seeks Nationwide Linguistic Revival, Voice of America (November 13, 2008)

- Vasyl Ivanyshyn, Yaroslav Radevych-Vynnyts'kyi, Mova i Natsiya Archived June 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, Drohobych, Vidrodzhennya, 1994, ISBN 5-7707-5898-8

- "the number of Ukrainian secondary schools has increased to 15,900, or 75% of their total number. In all, about 4.5 million students (67.4% of the total) are taught in Ukrainian, in Russian – 2.1 million (31.7%)..."

"Annual Report of the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights “On the situation with observance and protection of human rights and freedoms in Ukraine” for the period from April 14, 1998 till December 31, 1999" Archived May 2, 2006, at the Wayback Machine - Volodymyr Malynkovych, Ukrainian perspective, Politicheskiy Klass, January 2006

- Ukraine/ Compendium of Cultural Policies and Trends in Europe, 10th edition, Council of Europe (2009)

- Parliament of Crimea asks Yanukovych to allow testing in Russian language. Broadcasting Service of News (TSN). 17 February 2010

- The lowest amount of Ukrainian schools is in Crimea. Ukrayinska Pravda (Life). 30 March 2009

- In Crimea are being closed Ukrainian schools and classes. Radio Liberty. 11 April 2012

- Constitutional Court rules Russian, other languages can be used in Ukrainian courts, Kyiv Post (15 December 2011)

(in Ukrainian) З подачі "Регіонів" Рада дозволила російську у судах, Ukrayinska Pravda (23 June 2009)

(in Ukrainian) ЗМІ: Російська мова стала офіційною в українських судах Archived January 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Novynar (29 July 2010)

(in Ukrainian) Російська мова стала офіційною в українських судах, forUm (29 July 2010)