Nauru

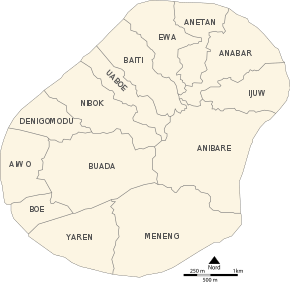

Nauru (/nɑːˈuːruː/ nah-OO-roo[8] or /ˈnaʊruː/ NOW-roo;[9] Nauruan: Naoero), officially the Republic of Nauru (Nauruan: Repubrikin Naoero) and formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country and microstate in Micronesia, a subregion of Oceania, in the Central Pacific. Its nearest neighbour is Banaba Island in Kiribati, 300 km (190 mi) to the east. It further lies northwest of Tuvalu, 1,300 km (810 mi) northeast of the Solomon Islands,[10] east-northeast of Papua New Guinea, southeast of the Federated States of Micronesia and south of the Marshall Islands. With only a 21 km2 (8.1 sq mi) area, Nauru is the third-smallest country in the world behind Vatican City, and Monaco, making it the smallest republic. Additionally, its population of 10,670 is the world's third smallest, after Vatican City and Tuvalu.

Republic of Nauru | |

|---|---|

Motto: "God's will first" | |

.svg.png) | |

| Capital | Yaren (de facto)[lower-alpha 1] 0°32′S 166°55′E |

| Largest city | Denigomodu |

| Official languages | Nauruan English[lower-alpha 2] |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Demonym(s) | Nauruan |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic under a non-partisan democracy |

| Lionel Aingimea | |

| Marcus Stephen | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Independence | |

| 31 January 1968 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 21 km2 (8.1 sq mi) (193rd) |

• Water (%) | 0.57 |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 10,670[4][5] (228th) |

• 2011 census | 10,084[6] |

• Density | 480/km2 (1,243.2/sq mi) (12th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $160 million[7] (192nd) |

• Per capita | $12,052[7] (94th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $114 million[7] |

• Per capita | $8,570[7] |

| Currency | Australian dollar (AUD) |

| Time zone | UTC+12 |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +674 |

| ISO 3166 code | NR |

| Internet TLD | .nr |

Settled by people from Micronesia and Polynesia c. 1000 BC, Nauru was annexed and claimed as a colony by the German Empire in the late 19th century. After World War I, Nauru became a League of Nations mandate administered by Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. During World War II, Nauru was occupied by Japanese troops, and was bypassed by the Allied advance across the Pacific. After the war ended, the country entered into United Nations trusteeship. Nauru gained its independence in 1968, and became a member of the Pacific Community (SPC) in 1969.

Nauru is a phosphate-rock island with rich deposits near the surface, which allowed easy strip mining operations. Its remaining phosphate resources are not economically viable for extraction.[11] When the phosphate reserves were exhausted, and the island's environment had been seriously harmed by mining, the trust that had been established to manage the island's wealth diminished in value. To earn income, Nauru briefly became a tax haven and illegal money laundering centre.[12] From 2001 to 2008, and again from 2012, it accepted aid from the Australian Government in exchange for hosting the Nauru Regional Processing Centre, an offshore Australian immigration detention facility. As a result of heavy dependence on Australia, some sources have identified Nauru as a client state of Australia.[13][14][15] The sovereign state is a member of the United Nations, Pacific Islands Forum, Commonwealth of Nations and the African, Caribbean, and Pacific Group of States.

History

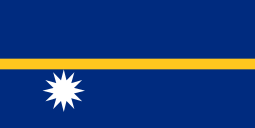

Nauru was first inhabited by Micronesians and Polynesians at least 3,000 years ago.[16] There were traditionally 12 clans or tribes on Nauru, which are represented in the twelve-pointed star on the country's flag.[17] Traditionally, Nauruans traced their descent matrilineally. Inhabitants practised aquaculture: they caught juvenile ibija fish, acclimatised them to freshwater, and raised them in the Buada Lagoon, providing a reliable source of food. The other locally grown components of their diet included coconuts and pandanus fruit.[18][19] The name "Nauru" may derive from the Nauruan word Anáoero, which means 'I go to the beach'.[20]

In 1798, the British sea captain John Fearn, on his trading ship Hunter (300 tons), became the first Westerner to report sighting Nauru, calling it "Pleasant Island", because of its attractive appearance.[21][22] From at least 1826, Nauruans had regular contact with Europeans on whaling and trading ships who called for provisions and fresh drinking water.[23] The last whaler to call during the age of sail visited in 1904.[24]

Around this time, deserters from European ships began to live on the island. The islanders traded food for alcoholic palm wine and firearms.[25] The firearms were used during the 10-year Nauruan Civil War that began in 1878.[26]

After an agreement with Great Britain, Nauru was annexed by Germany in 1888 and incorporated into Germany's Marshall Islands Protectorate for administrative purposes.[27][28] The arrival of the Germans ended the civil war, and kings were established as rulers of the island. The most widely known of these was King Auweyida. Christian missionaries from the Gilbert Islands arrived in 1888.[29][30] The German settlers called the island "Nawodo" or "Onawero".[31] The Germans ruled Nauru for almost three decades. Robert Rasch, a German trader who married a Nauruan woman, was the first administrator, appointed in 1890.[29]

Phosphate was discovered on Nauru in 1900 by the prospector Albert Fuller Ellis.[28][22] The Pacific Phosphate Company began to exploit the reserves in 1906 by agreement with Germany, exporting its first shipment in 1907.[21][32] In 1914, following the outbreak of World War I, Nauru was captured by Australian troops. In 1919 it was agreed by the Allied and Associated Powers that His Britannic Majesty should be the administering authority under a League of Nations mandate. The Nauru Island Agreement forged in 1919 between the governments of the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand provided for the administration of the island and extraction of the phosphate deposits by an intergovernmental British Phosphate Commission (BPC).[27][33] The terms of the League of Nations mandate were drawn up in 1920.[27][34]

The island experienced an influenza epidemic in 1920, with a mortality rate of 18 per cent among native Nauruans.[35]

In 1923, the League of Nations gave Australia a trustee mandate over Nauru, with the United Kingdom and New Zealand as co-trustees.[36] On 6 and 7 December 1940, the German auxiliary cruisers Komet and Orion sank five supply ships in the vicinity of Nauru. Komet then shelled Nauru's phosphate mining areas, oil storage depots, and the shiploading cantilever.[37][38]

Japanese troops occupied Nauru on 25 August 1942.[38] The Japanese built an airfield which was bombed for the first time on 25 March 1943, preventing food supplies from being flown to Nauru. The Japanese deported 1,200 Nauruans to work as labourers in the Chuuk Islands,[39] which was also occupied by Japan. As part of the Allied strategy of island hopping from the Pacific islands towards the main islands of Japan, Nauru was bypassed and left to "wither on the vine". Nauru was finally liberated on 13 September 1945, when commander Hisayaki Soeda surrendered the island to the Australian Army and the Royal Australian Navy.[40] The surrender was accepted by Brigadier J. R. Stevenson, who represented Lieutenant General Vernon Sturdee, the commander of the First Australian Army, aboard the warship HMAS Diamantina.[41][42] Arrangements were made to repatriate from Chuuk the 737 Nauruans who survived Japanese captivity there. They were returned to Nauru by the BPC ship Trienza in January 1946.[43]

In 1947, a trusteeship was established by the United Nations, with Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom as trustees.[44][45] Under those arrangements, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand were a joint administering authority. The Nauru Island Agreement provided for the first administrator to be appointed by Australia for five years, leaving subsequent appointments to be decided by the three governments.[27][34] However, in practice, administrative power was exercised by Australia alone.[27][34]

In 1948, Chinese guano mining workers went on strike over pay and conditions. The Administrator for Nauru, Eddie Ward, imposed a state of emergency with Native Police and armed volunteers of locals and Australian officials being mobilised. This force, using sub-machine guns and other firearms, opened fire on the Chinese workers killing two and wounding sixteen. Around 50 of the workers were arrested and two of these were bayoneted to death while in custody. The trooper who bayoneted the prisoners was charged but later acquitted on grounds that the wounds were "accidentally received."[46][47] The governments of the Soviet Union and China made official complaints against Australia at the United Nations over this incident.[48]

In 1964, it was proposed to relocate the population of Nauru to Curtis Island off the coast of Queensland, Australia. By that time, Nauru had been extensively mined for phosphate by companies from Australia, Britain and New Zealand damaging the landscape so much that it was thought the island would be uninhabitable by the 1990s. Rehabilitating the island was seen as financially impossible. In 1962, Australian Prime Minister, Bob Menzies, said that the three countries involved in the mining had an obligation to provide a solution for the Nauruan people, and proposed finding a new island for them. In 1963, the Australian Government proposed to acquire all the land on Curtis Island (which was considerably larger than Nauru) and then offer the Nauruans freehold title over the island and that the Nauruans would become Australian citizens.[49][50] The cost of resettling the Nauruans on Curtis Island was estimated to be £10 million, which included housing and infrastructure and the establishment of pastoral, agricultural, and fishing industries.[51] However, the Nauruan people did not wish to become Australian citizens and wanted to be given sovereignty over Curtis Island to establish themselves as an independent nation, which Australia would not agree to.[52] Nauru rejected the proposal to move to Curtis Island, instead choosing to become an independent nation operating their mines in Nauru.[53]

Nauru became self-governing in January 1966, and following a two-year constitutional convention, it became independent in 1968 under founding president Hammer DeRoburt.[54] In 1967, the people of Nauru purchased the assets of the British Phosphate Commissioners, and in June 1970 control passed to the locally owned Nauru Phosphate Corporation (NPC).[32] Income from the mines made Nauruans among the richest people in the world.[55][56] In 1989, Nauru took legal action against Australia in the International Court of Justice over Australia's administration of the island, in particular, Australia's failure to remedy the environmental damage caused by phosphate mining. Certain Phosphate Lands: Nauru v. Australia led to an out-of-court settlement to rehabilitate the mined-out areas of Nauru.[44][57]

Geography

Nauru is a 21 km2 (8.1 sq mi),[2] oval-shaped island in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, 55.95 km (34.77 mi) south of the equator.[58] The island is surrounded by a coral reef, which is exposed at low tide and dotted with pinnacles.[3] The presence of the reef has prevented the establishment of a seaport, although channels in the reef allow small boats access to the island.[59] A fertile coastal strip 150 to 300 m (490 to 980 ft) wide lies inland from the beach.[3]

Coral cliffs surround Nauru's central plateau. The highest point of the plateau, called the Command Ridge, is 71 m (233 ft) above sea level.[60]

The only fertile areas on Nauru are on the narrow coastal belt where coconut palms flourish. The land around Buada Lagoon supports bananas, pineapples, vegetables, pandanus trees, and indigenous hardwoods, such as the tamanu tree.[3]

Nauru was one of three great phosphate rock islands in the Pacific Ocean, along with Banaba (Ocean Island), in Kiribati, and Makatea, in French Polynesia. The phosphate reserves on Nauru are now almost entirely depleted. Phosphate mining in the central plateau has left a barren terrain of jagged limestone pinnacles up to 15 m (49 ft) high. Mining has stripped and devastated about 80 per cent of Nauru's land area, leaving it uninhabitable,[56] and has also affected the surrounding exclusive economic zone; 40 per cent of marine life is estimated to have been killed by silt and phosphate runoff.[3][61]

There are limited natural sources of freshwater on Nauru. Rooftop storage tanks collect rainwater. The islanders are mostly dependent on three desalination plants housed at Nauru's Utilities Agency.

Climate

Nauru's climate is hot and very humid year-round because of its proximity to the equator and the ocean. Nauru is hit by monsoon rains between November and February, but rarely has cyclones. Annual rainfall is highly variable and is influenced by the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, with several significant recorded droughts.[16][62] The temperature on Nauru ranges between 30 and 35 °C (86 and 95 °F) during the day and is quite stable at around 25 °C (77 °F) at night.[63]

Streams and rivers do not exist in Nauru. Water is gathered from roof catchment systems. Water is brought to Nauru as ballast on ships returning for loads of phosphate.[64]

| Climate data for Yaren District, Nauru | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34 (93) |

37 (99) |

35 (95) |

35 (95) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

35 (95) |

33 (91) |

35 (95) |

34 (93) |

36 (97) |

35 (95) |

37 (99) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30 (86) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

31 (88) |

31 (88) |

31 (88) |

30 (87) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 21 (70) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

20 (68) |

21 (70) |

20 (68) |

21 (70) |

20 (68) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

20 (68) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 280 (11.0) |

250 (9.8) |

190 (7.5) |

190 (7.5) |

120 (4.7) |

110 (4.3) |

150 (5.9) |

130 (5.1) |

120 (4.7) |

100 (3.9) |

120 (4.7) |

280 (11.0) |

2,080 (81.9) |

| Average precipitation days | 16 | 14 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 14 | 11 | 10 | 13 | 15 | 152 |

| Source: | |||||||||||||

Ecology

Fauna is sparse on the island because of a lack of vegetation and the consequences of phosphates mining. Many indigenous birds have disappeared or become rare owing to the destruction of their habitat.[65] There are about 60 recorded vascular plant species native to the island, none of which are endemic. Coconut farming, mining, and introduced species have seriously disturbed the native vegetation.[16]

There are no native land mammals, but there are native insects, land crabs, and birds, including the endemic Nauru reed warbler. The Polynesian rat, cats, dogs, pigs, and chickens have been introduced to Nauru from ships.[66] The diversity of the reef marine life makes fishing a popular activity for tourists on the island; also popular are scuba diving and snorkelling.[67]

Politics

The president of Nauru is Lionel Aingimea, who heads a 19-member unicameral parliament. The country is a member of the United Nations, the Commonwealth of Nations, the Asian Development Bank and the Pacific Islands Forum. Nauru also participates in the Commonwealth and Olympic Games. Recently Nauru became a member country of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). The Republic of Nauru became the 189th member of the International Monetary Fund in April 2016.

Nauru is a republic with a parliamentary system of government.[54] The president is both head of state and head of government and is dependent on parliamentary confidence to remain president. A 19-member unicameral parliament is elected every three years.[68] The parliament elects the president from its members, and the president appoints a cabinet of five to six members.[69]

Nauru does not have any formal structure for political parties, and candidates typically stand for office as independents; fifteen of the 19 members of the current Parliament are independents. Four parties that have been active in Nauruan politics are the Nauru Party, the Democratic Party, Nauru First and the Centre Party. However, alliances within the government are often formed based on of extended family ties rather than party affiliation.[70]

From 1992 to 1999, Nauru had a local government system known as the Nauru Island Council (NIC). This nine-member council was designed to provide municipal services. The NIC was dissolved in 1999 and all assets and liabilities became vested in the national government.[71] Land tenure on Nauru is unusual: all Nauruans have certain rights to all land on the island, which is owned by individuals and family groups. Government and corporate entities do not own any land, and they must enter into a lease arrangement with landowners to use land. Non-Nauruans cannot own land on the island.[16]

Nauru had 17 changes of administration between 1989 and 2003.[72] Bernard Dowiyogo died in office in March 2003 and Ludwig Scotty was elected as the president, later being re-elected to serve a full term in October 2004. Following a vote of no confidence on 19 December 2007, Scotty was replaced by Marcus Stephen. Stephen resigned in November 2011, and Freddie Pitcher became President. Sprent Dabwido then filed a motion of no confidence in Pitcher, resulting in him becoming president.[73][74] Following parliamentary elections in 2013, Baron Waqa was elected president.

Its Supreme Court, headed by the Chief Justice, is paramount on constitutional issues. Other cases can be appealed to the two-judge Appellate Court. Parliament cannot overturn court decision. Historically, Appellate Court rulings could be appealed to the High Court of Australia,[75][76] though this happened only rarely and the Australian court's appellate jurisdiction ended entirely on 12 March 2018 after the Government of Nauru unilaterally ended the arrangement.[77][78][79] Lower courts consist of the District Court and the Family Court, both of which are headed by a Resident Magistrate, who also is the Registrar of the Supreme Court. There are two other quasi-courts: the Public Service Appeal Board and the Police Appeal Board, both of which are presided over by the Chief Justice.[3]

Foreign relations

Following independence in 1968, Nauru joined the Commonwealth of Nations as a Special Member; it became a full member in 2000.[80] The country was admitted to the Asian Development Bank in 1991 and the United Nations in 1999.[81] Nauru is a member of the Pacific Islands Forum, the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme, the South Pacific Commission, and the South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission.[82] The US Atmospheric Radiation Measurement program operates a climate-monitoring facility on the island.[83]

.jpg)

Nauru has no armed forces, though there is a small police force under civilian control.[2] Australia is responsible for Nauru's defence under an informal agreement between the two countries.[2] The September 2005 memorandum of understanding between Australia and Nauru provides the latter with financial aid and technical assistance, including a Secretary of Finance to prepare the budget, and advisers on health and education. This aid is in return for Nauru's housing of asylum seekers while their applications for entry into Australia are processed.[72] Nauru uses the Australian dollar as its official currency.[3]

Nauru has used its position as a member of the United Nations to gain financial support from both Taiwan (officially the Republic of China or ROC) and mainland China (officially the People's Republic of China or PRC) by changing its recognition from one to the other under the One-China policy. On 21 July 2002, Nauru signed an agreement to establish diplomatic relations with the PRC, accepting US$130 million from the PRC for this action.[84] In response, the ROC severed diplomatic relations with Nauru two days later. Nauru later re-established links with the ROC on 14 May 2005,[85] and diplomatic ties with the PRC were officially severed on 31 May 2005.[86] However, the PRC continues to maintain a representative office on Nauru.[87]

In 2008, Nauru recognised Kosovo as an independent country, and in 2009 Nauru became the fourth country, after Russia, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, to recognise Abkhazia, a breakaway region of Georgia. Russia was reported to be giving Nauru US$50 million in humanitarian aid as a result of this recognition.[84] On 15 July 2008, the Nauruan government announced a port refurbishment programme, financed with US$9 million of development aid received from Russia. The Nauru government claims this aid is not related to its recognising Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[88]

.jpg)

A significant portion of Nauru's income has been in the form of aid from Australia. In 2001, the MV Tampa, a Norwegian ship that had rescued 438 refugees from a stranded 20-metre-long boat, was seeking to dock in Australia. In what became known as the Tampa affair, the ship was refused entry and boarded by Australian troops. The refugees were eventually loaded onto Royal Australian Navy vessel HMAS Manoora and taken to Nauru to be held in detention facilities which later became part of the Howard government's Pacific Solution. Nauru operated two detention centres known as State House and Topside for these refugees in exchange for Australian aid.[89] By November 2005, only two refugees, Mohammed Sagar and Muhammad Faisal remained on Nauru from those first sent there in 2001,[90] with Sagar finally resettling in early 2007. The Australian government sent further groups of asylum-seekers to Nauru in late 2006 and early 2007.[91] The refugee centre was closed in 2008,[3] but, following the Australian government's re-adoption of the Pacific Solution in August 2012, it has re-opened it.[92]

In March 2017, at the 34th regular session of the UN Human Rights Council, Vanuatu made a joint statement on behalf of Nauru and some other Pacific nations raising human rights violations in the Western New Guinea, which has been occupied by Indonesia since 1963,[93] and requested that the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights produced a report.[94][95] Indonesia rejected allegations.[95] More than 100,000 Papuans have died during a 50-year Papua conflict.[96]

Amnesty International has since described the conditions of the refugees of war living in Nauru, as a "horror",[97][98] with reports of children as young as eight attempting suicide and engaging in acts of self-harm.[99] In 2018, the situation gained attention as a "mental health crisis", with an estimated thirty children suffering from traumatic withdrawal syndrome, also known as resignation syndrome. The condition is a deteriorating psychiatric condition wherein the sufferer can eventually become unresponsive and their body can begin to shut down. This condition has also been observed in other groups of asylum seekers.[99][100]

Administrative divisions

Nauru is divided into fourteen administrative districts which are grouped into eight electoral constituencies and are further divided into villages.[3][2] The most populous district is Denigomodu with 1,804 residents, of which 1,497 reside in an NPC settlement called "Location". The following table shows population by district according to the 2011 census.[101]

|

Economy

The Nauruan economy peaked in the mid-1970s, when its GDP per capita was estimated to be US$50,000, second only to Saudi Arabia.[56] Most of this came from phosphate mining, which declined from the early 1980s.[102]:5 There are few other resources, and most necessities are imported.[3][103] Small-scale mining is still conducted by RONPhos, formerly known as the Nauru Phosphate Corporation.[3] The government places a percentage of RONPhos's earnings into the Nauru Phosphate Royalties Trust. The trust manages long-term investments, which were intended to support the citizens after the phosphate reserves were exhausted.[104]

Because of mismanagement, the trust's fixed and current assets were reduced considerably and may never fully recover. The failed investments included financing Leonardo the Musical in 1993.[105] The Mercure Hotel in Sydney[106] and Nauru House in Melbourne were sold in 2004 to finance debts and Air Nauru's only Boeing 737 was repossessed in December 2005. Normal air service resumed after the aircraft was replaced with a Boeing 737-300 airliner in June 2006.[107] In 2005, the corporation sold its remaining real estate in Melbourne, the vacant Savoy Tavern site, for $7.5 million.[108]

The value of the trust is estimated to have shrunk from A$1.3 billion in 1991 to A$138 million in 2002.[109] Nauru currently lacks money to perform many of the basic functions of government; for example, the National Bank of Nauru is insolvent. The CIA World Factbook estimated a GDP per capita of US$5,000 in 2005.[2] The Asian Development Bank 2007 economic report on Nauru estimated GDP per capita at US$2,400 to US$2,715.[102] The United Nations (2013) estimates the GDP per capita to 15,211 and ranks it 51 on its GDP per capita country list.

There are no personal taxes in Nauru. The unemployment rate is estimated to be 23 percent, and of those who have jobs, the government employs 95 per cent.[2][110] The Asian Development Bank notes that, although the administration has a strong public mandate to implement economic reforms, in the absence of an alternative to phosphate mining, the medium-term outlook is for continued dependence on external assistance.[109] Tourism is not a major contributor to the economy.[111]

.jpg)

In the 1990s, Nauru became a tax haven and offered passports to foreign nationals for a fee.[112] The inter-governmental Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF) identified Nauru as one of 15 "non-cooperative" countries in its fight against money laundering. During the 1990s, it was possible to establish a licensed bank in Nauru for only US$25,000 with no other requirements. Under pressure from FATF, Nauru introduced anti-avoidance legislation in 2003, after which foreign hot money left the country. In October 2005, after satisfactory results from the legislation and its enforcement, FATF lifted the non-cooperative designation.[113]

From 2001 to 2007, the Nauru detention centre provided a significant source of income for the country. The Nauruan authorities reacted with concern to its closure by Australia.[114] In February 2008, the Foreign Affairs minister, Dr Kieren Keke, stated that the closure would result in 100 Nauruans losing their jobs, and would affect 10 per cent of the island's population directly or indirectly: "We have got a huge number of families that are suddenly going to be without any income. We are looking at ways we can try and provide some welfare assistance but our capacity to do that is very limited. Literally we have got a major unemployment crisis in front of us."[115] The detention centre was re-opened in August 2012.[92]

In July 2017 the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) upgraded its rating of Nauru's standards of tax transparency. Previously Nauru had been listed alongside fourteen other countries that had failed to show that they could comply with international tax transparency standards and regulations. The OECD subsequently put Nauru through a fast-tracked compliance process and the country was given a "largely compliant" rating.[116]

The Nauru 2017–2018 budget, delivered by Minister for Finance David Adeang, forecasted A$128.7 million in revenues and A$128.6 million in expenditures and projected modest economic growth for the nation over the next two years.[117]

Population

Demographics

Nauru had 10,670 residents as of July 2018, making it the second smallest sovereign state after Vatican City.[4][5] The population was previously larger, but in 2006 1,500 people left the island during a repatriation of immigrant workers from Kiribati and Tuvalu. The repatriation was motivated by large force reductions in phosphate mining.[102]

Nauru is one of the most Westernized countries in the South Pacific.[118]

Ethnic groups

Fifty-eight percent of people in Nauru are ethnically Nauruan, 26 percent are other Pacific Islander, 8 percent are European, and 8 percent are Han Chinese.[2] Nauruans descended from Polynesian and Micronesian seafarers. Two of the 12 original tribal groups became extinct in the 20th century.[3]

Languages

The official language of Nauru is Nauruan,[1] a distinct Micronesian language, which is spoken by 96 per cent of ethnic Nauruans at home.[102] English is widely spoken and is the language of government and commerce, as Nauruan is not used outside of the country.[2][3]

Religion

.jpg)

The main religion practised on the island is Christianity (the main denominations are Nauru Congregational Church 35.71%, Roman Catholic 32.96% Assemblies of God 12.98% and Baptist 1.48%).[3] The Constitution provides for freedom of religion. The government has restricted the religious practices of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Jehovah's Witnesses, most of whom are foreign workers employed by the government-owned Nauru Phosphate Corporation.[119] The Catholics are pastorally served by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Tarawa and Nauru, with see at Tarawa in Kiribati.

Culture

Angam Day, held on 26 October, celebrates the recovery of the Nauruan population after the two World Wars and the 1920 influenza epidemic.[120] The displacement of the indigenous culture by colonial and contemporary Western influences is significant.[121] Few of the old customs have been preserved, but some forms of traditional music, arts and crafts, and fishing are still practised.[122]

Media

There are no daily news publications on Nauru, although there is one fortnightly publication, Mwinen Ko. There is a state-owned television station, Nauru Television (NTV), which broadcasts programs from New Zealand and Australia, and a state-owned non-commercial radio station, Radio Nauru, which carries programs from Radio Australia and the BBC.[123]

Sport

Australian rules football is the most popular sport in Nauru—it and weightlifting are considered the country's national sports. There is an Australian rules football league with eight teams.[124] Other sports popular in Nauru include volleyball, netball, fishing and tennis. Nauru participates in the Commonwealth Games and has participated in the Summer Olympic Games in weightlifting and judo.[125]

Nauru's national basketball team competed at the 1969 Pacific Games, where it defeated the Solomon Islands and Fiji.

Rugby sevens popularity has increased over the last two years, so much so that they have a national team.

Nauru competed in the 2015 Oceania Sevens Championship in New Zealand.

Holidays

Independence Day is celebrated on 31 January.[126]

Public services

Education

Literacy on Nauru is 96 per cent. Education is compulsory for children from six to sixteen years old, and two more non-compulsory years are offered (years 11 and 12).[127] The island has three primary schools and two secondary schools, the latter being Nauru College and Nauru Secondary School.[128] There is a campus of the University of the South Pacific on Nauru. Before this campus was built in 1987, students would study either by distance or abroad.[129] Since 2011, the University of New England, Australia has established a presence on the island with around 30 Nauruan teachers studying for an associate degree in education. These students will continue onto the degree to complete their studies.[130] This project is led by Associate Professor Pep Serow and funded by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

The previous community public library was destroyed in a fire. As of 1999 a new one had not yet been built, and no bookmobile services are available as of that year. Sites with libraries include the University of the South Pacific campus, Nauru Secondary, Kayser College, and Aiwo Primary.[131] The Nauru Community Library is in the new University of the South Pacific Nauru Campus building, which was officially opened in May 2018.

Health

Life expectancy on Nauru in 2009 was 60.6 years for males and 68.0 years for females.[133]

By measure of mean body mass index (BMI), Nauruans are the most overweight people in the world;[132] 97 per cent of men and 93 per cent of women are overweight or obese.[132] In 2012, the obesity rate was 71.7 per cent.[134] Obesity in the Pacific islands is common.

Nauru has the world's highest level of type 2 diabetes, with more than 40 per cent of the population affected.[135] Other significant dietary-related problems on Nauru include kidney disease and heart disease.[133]

Transport

Air

The island is solely served by Nauru International Airport. Passenger service is provided by Nauru Airlines, with Pacific Air Express also providing cargo service. Flights operate five days a week to well connected airports such as Brisbane and Nadi.[136]

Notes

- Nauru does not have an official capital, but Yaren is the seat of parliament.[1]

- English is not an official language, but it is widely spoken by the majority of the population and it is commonly used in government, legislation and commerce alongside Nauruan. Due to Nauru's history and relationship with Australia, Australian English is the dominant variety.[2][3] And is de facto official.

References

Citations

- Worldwide Government Directory with Intergovernmental Organizations. CQ Press. 2013. p. 1131.

- Central Intelligence Agency (2015). "Nauru". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- "Background Note: Nauru". State Department Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs. September 2005. Retrieved 11 May 2006.

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "National Report on Population ad Housing" (PDF). Nauru Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org.

- "Nauru Pronunciation in English". Cambridge English Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Nauru – Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes". Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- "Yaren | district, Nauru". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Hogan, C Michael (2011). "Phosphate". Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- Hitt, Jack (10 December 2000). "The Billion-Dollar Shack". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 January 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "Pacific correspondent Mike Field". Radio New Zealand. 18 June 2015. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "Nauru's former chief justice predicts legal break down". Special Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- Ben Doherty. "This is Abyan's story, and it is Australia's story". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- Nauru Department of Economic Development and Environment (2003). "First National Report to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification" (PDF). United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- Whyte, Brendan (2007). "On Cartographic Vexillology". Cartographica. 42 (3): 251–262. doi:10.3138/carto.42.3.251.

- Pollock, Nancy J (1995). "5: Social Fattening Patterns in the Pacific—the Positive Side of Obesity. A Nauru Case Study". In De Garine, I (ed.). Social Aspects of Obesity. Routledge. pp. 87–111.

- Spennemann, Dirk HR (January 2002). "Traditional milkfish aquaculture in Nauru". Aquaculture International. 10 (6): 551–562. doi:10.1023/A:1023900601000.

- West, Barbara A (2010). "Nauruans: nationality". Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. pp. 578–580. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- Maslyn Williams & Barrie Macdonald (1985). The Phosphateers. Melbourne University Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-522-84302-6.

- Ellis, Albert F. (1935). Ocean Island and Nauru; Their Story. Sydney, Australia: Angus and Robertson, limited. p. 29. OCLC 3444055.

- Langdon, Robert (1984), Where the whalers went: an index to the Pacific ports and islands visited by American whalers (and some other ships) in the 19th century, Canberra, Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, p.180. ISBN 086784471X

- Langdon, p.182

- Marshall, Mac; Marshall, Leslie B (January 1976). "Holy and Unholy Spirits: The Effects of Missionization on Alcohol Use in Eastern Micronesia". Journal of Pacific History. 11 (3): 135–166. doi:10.1080/00223347608572299.

- Reyes, Ramon E. Jr (1996). "Nauru v. Australia". New York Law School Journal of International and Comparative Law. 16 (1–2). Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- "Commonwealth and Colonial Law" by Kenneth Roberts-Wray, London, Stevens, 1966. p. 884

- Firth, Stewart (January 1978). "German Labour Policy in Nauru and Angaur, 1906–1914". The Journal of Pacific History. 13 (1): 36–52. doi:10.1080/00223347808572337.

- Hill, Robert A, ed. (1986). "2: Progress Comes to Nauru". The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers. 5. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05817-0.

- Ellis, AF (1935). Ocean Island and Nauru – their story. Angus and Robertson Limited. pp. 29–39.

- Hartleben, A (1895). Deutsche Rundschau für Geographie und Statistik. p. 429.

- Manner, HI; Thaman, RR; Hassall, DC (May 1985). "Plant succession after phosphate mining on Nauru". Australian Geographer. 16 (3): 185–195. doi:10.1080/00049188508702872.

- Gowdy, John M; McDaniel, Carl N (May 1999). "The Physical Destruction of Nauru". Land Economics. 75 (2): 333–338. doi:10.2307/3147015. JSTOR 3147015.

- Cmd. 1202

- Shlomowitz, R (November 1990). "Differential mortality of Asians and Pacific Islanders in the Pacific labour trade". Journal of the Australian Population Association. 7 (2): 116–127. doi:10.1007/bf03029360 (inactive 29 April 2020). PMID 12343016.

- Hudson, WJ (April 1965). "Australia's experience as a mandatory power". Australian Outlook. 19 (1): 35–46. doi:10.1080/10357716508444191.

- Waters, SD (2008). German raiders in the Pacific (3rd ed.). Merriam Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-4357-5760-8.

- Bogart, Charles H (November 2008). "Death off Nauru" (PDF). CDSG Newsletter: 8–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- Haden, JD (2000). "Nauru: a middle ground in World War II". Pacific Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- Takizawa, Akira; Alsleben, Allan (1999–2000). "Japanese garrisons on the by-passed Pacific Islands 1944–1945". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016.

- The Times, 14 September 1945

- "Nauru Occupied by Australians; Jap Garrison and Natives Starving". The Argus. 15 September 1945. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- Garrett, J (1996). Island Exiles. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. pp. 176–181. ISBN 0-7333-0485-0.

- Highet, K; Kahale, H (1993). "Certain Phosphate Lands in Nauru". American Journal of International Law. 87 (2): 282–288. doi:10.2307/2203821. JSTOR 2203821. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- Cmd. 7290

- "NAURU RIOT". Townsville Daily Bulletin. Queensland, Australia. 2 July 1949. p. 1. Retrieved 17 February 2020 – via Trove.

- "Chinese Lose Nauru and Manus Cases", Pacific Islands Monthly, [Sydney: Pacific Publications (Vol. XIX, No. 6 ( Jan. 1, 1949)), 1949, nla.obj-330063007, retrieved 17 February 2020 – via Trove

- "Nauru, New Guinea". The Courier-mail. Queensland, Australia. 5 October 1949. p. 4. Retrieved 17 February 2020 – via Trove.

- "Island Purchase For Nauruans". The Canberra Times. 38 (10, 840). Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 6 May 1964. p. 5. Retrieved 1 April 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Nauruans Likely To Settle Curtis Island". The Canberra Times. 37 (10, 549). Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 30 May 1963. p. 9. Retrieved 1 April 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- McAdam, Jane (15 August 2016). "How the entire nation of Nauru almost moved to Queensland". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- "Lack of Sovereignty 'Disappoints' Nauruans". The Canberra Times. 37 (10, 554). Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 5 June 1963. p. 45. Retrieved 1 April 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Nauru not to take Curtis Is". The Canberra Times. 38 (10, 930). Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 21 August 1964. p. 3. Retrieved 1 April 2019 – via National Library of Australia.

- Davidson, JW (January 1968). "The Republic of Nauru". The Journal of Pacific History. 3 (1): 145–150. doi:10.1080/00223346808572131.

- Squires, Nick (15 March 2008). "Nauru seeks to regain lost fortunes". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on 20 March 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- Watanabe, Anna (16 September 2018). "From economic haven to refugee 'hell'". Kyodo News. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- Case Concerning Certain Phosphate Lands in Nauru (Nauru v. Australia) Application: Memorial of Nauru. ICJ Pleadings, Oral Arguments, Documents. United Nations, International Court of Justice. January 2004. ISBN 978-92-1-070936-1.

- Google Map Developers. "Distance Finder". Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- Thaman, RR; Hassall, DC. "Nauru: National Environmental Management Strategy and National Environmental Action Plan" (PDF). South Pacific Regional Environment Programme. p. 234. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- Jacobson, Gerry; Hill, Peter J; Ghassemi, Fereidoun (1997). "24: Geology and Hydrogeology of Nauru Island". In Vacher, H Leonard; Quinn, Terrence M (eds.). Geology and hydrogeology of carbonate islands. Elsevier. p. 716. ISBN 978-0-444-81520-0.

- "Climate Change – Response" (PDF). First National Communication. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- Affaire de certaines terres à phosphates à Nauru. International Court of Justice. 2003. pp. 107–109. ISBN 978-92-1-070936-1.

- "Pacific Climate Change Science Program" (PDF). Government of Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- "Yaren | district, Nauru". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "NAURU Information on Government, People, History, Economy, Environment, Development". Archived from the original on 27 July 2013.

- BirdLife International. "Important Bird Areas in Nauru". Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environmental Programme. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- "Nauru Ecotourism Tours – Sustainable Tourism & Conservation Laws". Archived from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- Matau, Robert (6 June 2013) "President Dabwido gives it another go" Archived 26 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine . Islands Business.

- Levine, Stephen; Roberts, Nigel S (November 2005). "The constitutional structures and electoral systems of Pacific Island states". Commonwealth & Comparative Politics. 43 (3): 276–295. doi:10.1080/14662040500304866.

- Anckar, D; Anckar, C (2000). "Democracies without Parties". Comparative Political Studies. 33 (2): 225–247. doi:10.1177/0010414000033002003.

- Hassell, Graham; Tipu, Feue (May 2008). "Local Government in the South Pacific Islands". Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance. 1 (1): 6–30. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- "Republic of Nauru Country Brief". Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. November 2005. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2006.

- Connell, John (January 2006). "Nauru: The first failed Pacific State?". The Round Table. 95 (383): 47–63. doi:10.1080/00358530500379205.

- "Nauru profile". BBC News Online. 24 October 2011. Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- "Nauru (High Court Appeals) Act (Australia) 1976". Australian Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 7 August 2006.

- Dale, Gregory (2007). "Appealing to Whom? Australia's 'Appellate Jurisdiction' Over Nauru". International & Comparative Law Quarterly. 56 (3): 641–658. doi:10.1093/iclq/lei186.

- Gans, Jeremy (20 February 2018). "News: Court may lose Nauru appellate role". Opinions on High. Melbourne Law School, The University of Melbourne. Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Clarke, Melissa (2 April 2018). "Justice in Nauru curtailed as Government abolishes appeal system". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Wahlquist, Calla (2 April 2018). "Fears for asylum seekers as Nauru moves to cut ties to Australia's high court". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "Republic of Nauru Permanent Mission to the United Nations". United Nations. Archived from the original on 18 August 2006. Retrieved 10 May 2006.

- "Nauru in the Commonwealth". Commonwealth of Nations. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- "Nauru (04/08)". US State Department. 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- Long, Charles N; McFarlane, Sally A (March 2012). "Quantification of the Impact of Nauru Island on ARM Measurements". Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology. 51 (3): 628–636. Bibcode:2012JApMC..51..628L. doi:10.1175/JAMC-D-11-0174.1.

- Harding, Luke (14 December 2009). "Tiny Nauru struts world stage by recognising breakaway republics". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 December 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- Su, Joy (15 May 2005). "Nauru switches its allegiance back to Taiwan from China". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- "China officially severs diplomatic ties with Nauru". Asia Africa Intelligence Wire. 31 May 2005. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- "Chinese Embassy in Nauru". Gov.cn. 18 January 2006. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- "Nauru expects to earn more from exports after port upgrade with Russian aid". Radio New Zealand International. 15 July 2010. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- White, Michael (2002). "M/V Tampa Incident and Australia's Obligations – August 2001". Maritime Studies. doi:10.1080/07266472.2002.10878659. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- Gordon, M (5 November 2005). "Nauru's last two asylum seekers feel the pain". The Age. Archived from the original on 4 June 2008. Retrieved 8 May 2006.

- "Nauru detention centre costs $2m per month". ABC News. 12 February 2007. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2007.

- "Asylum bill passes parliament". The Daily Telegraph. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- "Freedom of the press in Indonesian-occupied West Papua". The Guardian. 22 July 2019.

- Fox, Liam (2 March 2017). "Pacific nations call for UN investigations into alleged Indonesian rights abuses in West Papua". ABC News.

- "Pacific nations want UN to investigate Indonesia on West Papua". SBS News. 7 March 2017.

- "Goodbye Indonesia". Al-Jazeera. 31 January 2013.

- "'It's better to die from one bullet than being slowly killed every day' – refugees forsaken on Nauru". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- "Life for asylum seekers in Australia's 'Pacific Gulag' on Nauru". South China Morning Post (SCMP). Agence France-Presse (AFP). 11 September 2018. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- Harrison, Virginia. "Nauru refugees: The island where children have given up on life". BBC. BBC. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "Five years on Nauru". Reveal. 16 February 2019. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- "Nauru—The population of the districts of the Republic of Nauru". City Population. 2011. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- "Country Economic Report: Nauru" (PDF). Asian Development Bank. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- "Big tasks for a small island". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on 13 August 2006. Retrieved 10 May 2006.

- Seneviratne, Kalinga (26 May 1999). "Nauru turns to dust". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- Mellor, William (1 June 2004). "GE Poised to Bankrupt Nauru, Island Stained by Money-Laundering". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- Skehan, Craig (9 July 2004). "Nauru, receivers start swapping legal blows". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- "Receivers take over Nauru House". The Age. 18 April 2004. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- "Nauru sells last remaining property asset in Melbourne". RNZ Pacific. 9 April 2005. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Asian Development Outlook 2005 – Nauru". Asian Development Bank. 2005. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2006.

- "Paradise well and truly lost". The Economist. 20 December 2001. Archived from the original on 30 November 2006. Retrieved 2 May 2006.

- "Nauru". Pacific Islands Trade and Investment Commission. Archived from the original on 21 July 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- "The Billion Dollar Shack". The New York Times. 10 December 2000. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- "Nauru de-listed" (PDF). FATF. 13 October 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2005. Retrieved 11 May 2006.

- Topsfield, Hewel (11 December 2007). "Nauru fears gap when camps close". The Age. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- "Nauru 'hit' by detention centre closure". The Age. 7 February 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- "Nauru gets an OECD upgrade". 12 July 2017. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- "Modest economic growth forecast for Nauru". Loop Pacific. 12 June 2017. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- "Yaren | district, Nauru". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "International Religious Freedom Report 2003 – Nauru". US Department of State. 2003. Retrieved 2 May 2005.

- "Nauru Celebrates Angam Day". United Nations. Archived from the original on 21 October 2004. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- Nazzal, Mary (April 2005). "Nauru: an environment destroyed and international law" (PDF). lawanddevelopment.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- "Culture of Nauru". Republic of Nauru. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- "Country Profile: Nauru". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 2 May 2006.

- "Nauru Australian Football Association". Australian Football League. Archived from the original on 31 December 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- "Nauru Olympic Committee History". Nauru Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- Stahl, Dean A.; Landen, Karen (2001). Abbreviations Dictionary (10 ed.). CRC Press. p. 1436. ISBN 9781420036640. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- Waqa, B (1999). "UNESCO Education for all Assessment Country report 1999 Country: Nauru". Archived from the original on 25 May 2006. Retrieved 2 May 2006.

- "Schools Archived 5 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine." Government of Nauru. Retrieved on 5 June 2018.

- "USP Nauru Campus". University of the South Pacific. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- "Nauru Teacher Education Project". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- Book Provision in the Pacific Islands. UNESCO Pacific States Office, 1999. ISBN 9820201551, 9789820201552. p. 33 Archived 5 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Fat of the land: Nauru tops obesity league". The Independent. 26 December 2010. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- "Nauru". World health report 2005. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 18 April 2006. Retrieved 2 May 2006.

- Nishiyama, Takkaki (27 May 2012). "Nauru: An island plagued by obesity and diabetes". Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- King, H; Rewers M (1993). "Diabetes in adults is now a Third World problem". Ethnicity & Disease. 3: S67–74.

- "Flight schedule for Nauru Airlines". Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

Sources

Further reading

- Gowdy, John M.; McDaniel, Carl N. (2000). Paradise for Sale: A Parable of Nature. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22229-8.

- Williams, Maslyn; Macdonald, Barrie (1985). The Phosphateers. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84302-6.

External links

- Government of Nauru

- Nauru National Tourism Office

- "Nauru". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Nauru at Curlie

- Nauru from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Nauru profile from the BBC News Online

.svg.png)