Catholic Bible

A Catholic Bible is a Christian Bible that includes the whole 73-book canon recognized by the Catholic Church, including the deuterocanonical books.

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

Miscellaneous

Relations with: |

|

|

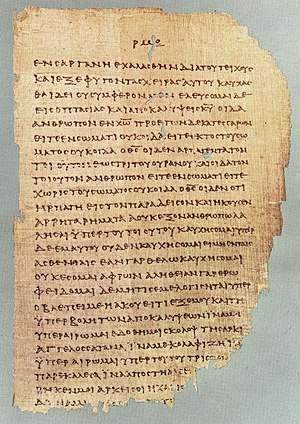

The term "deuterocanonical" is used by some scholars to denote the books (and parts of books) of the Old Testament which are in the Greek Septuagint collection but not in the Hebrew Masoretic Text collection. The Canon of Scripture of the Old Testament recognized by the Catholic Church is based on the Septuagint version of the Old Testament because, while both the Hebrew scriptures and the Septuagint were used in the time of Christ, the Septuagint was used by the apostles and Early Christianity in the universal proclamation of the Gospel. Indeed, most of the quotations from the Old Testament appearing in the New Testament books are from the Septuagint, not the Hebrew scriptures.[1] The Catholic Church, at the Council of Rome (382), when it settled the list of Scripture (46 books in O.T., 27 books in N.T., total 73 books), did not accept some of the books of the Septuagint as being inspired and canonical: namely, the Book of Enoch, 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, and some others.

Lectionaries for use in the liturgy differ somewhat in text from the Bible versions on which they are based. The Vulgate is the official Bible translation of the Latin Church, but translating from the original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek has been encouraged since Pius XII issued the encyclical letter Divino afflante Spiritu in 1943.

Books included

The Catholic Bible is composed of the 46 books of the Old Testament and the 27 books of the New Testament.

Old Testament

- Pentateuch : Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy

- Historical books : Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1 Samuel, 2 Samuel, 1 Kings, 2 Kings, 1 Chronicles, 2 Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah, Tobit, Judith, Esther, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees

- Wisdom books : Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach

- Prophetic books : Isaiah, Jeremiah, Lamentations, Baruch, Ezekiel, Daniel, Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi

Of these books, Tobit, Judith, 1 and 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, are the deuterocanonical books of the Bible.

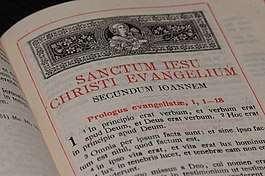

New Testament

- The Gospels : Matthew, Mark, Luke, John

- Historical book : Acts

- Pauline epistles : Romans, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 Thessalonians, 2 Thessalonians, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon, Hebrews

- General epistles : James, 1 Peter, 2 Peter, 1 John, 2 John, 3 John, Jude

- Revelation

Canon law

In another sense, a "Catholic Bible" is a Bible published in accordance with the prescriptions of Catholic canon law, which states:

Books of the sacred scriptures cannot be published unless the Apostolic See or the conference of bishops has approved them. For the publication of their translations into the vernacular, it is also required that they be approved by the same authority and provided with necessary and sufficient annotations. With the permission of the Conference of Bishops, Catholic members of the Christian faithful in collaboration with separated brothers and sisters can prepare and publish translations of the sacred scriptures provided with appropriate annotations.[2]

— Canon 825 of the 1983 Code of canon Law

Divine Revelation, in the form of the New Testament, serves as a source of canon law.

Principles of translation

Without diminishing the authority of the texts of the books of Scripture in the original languages, the Council of Trent declared the Vulgate the official translation of the Bible for the Latin Church, but did not forbid the making of translations directly from the original languages.[3][4] Before the middle of the 20th century, Catholic translations were often made from that text rather than from the original languages. Thus Ronald Knox, the author of what has been called the Knox Bible, wrote: "When I talk about translating the Bible, I mean translating the Vulgate."[5] Today, the version of the Bible that is used in official documents in Latin is the Nova Vulgata, a revision of the Vulgate.[6]

The original Bible text is, according to Catholics, "written by the inspired author himself and has more authority and greater weight than any, even the very best, translation whether ancient or modern".[7]

The principles expounded in Pope Pius XII's encyclical Divino afflante Spiritu regarding exegesis or interpretation, as in commentaries on the Bible, apply also to the preparation of a translation. These include the need for familiarity with the original languages and other cognate languages, the study of ancient codices and even papyrus fragments of the text and the application to them of textual criticism, "to insure that the sacred text be restored as perfectly as possible, be purified from the corruptions due to the carelessness of the copyists and be freed, as far as may be done, from glosses and omissions, from the interchange and repetition of words and from all other kinds of mistakes, which are wont to make their way gradually into writings handed down through many centuries".[8]

Catholic English versions

The following are English versions of the Bible that correspond to this description:

| Abbreviation | Name | Date |

|---|---|---|

| DRB | Douay-Rheims Bible | 1582, 1609, 16101 |

| DRB | Douay-Rheims Bible Challoner Revision | 1749-1752 |

| WVSS | Westminster Version of the Sacred Scripture[9] | 1913–19352 |

| SPC | Spencer New Testament[10] | 1941 |

| CCD | Confraternity Bible | 19413 |

| Knox | Knox Bible | 1950 |

| KLNT | Kleist–Lilly New Testament | 19564 |

| RSV–CE | Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition | 1965–66 |

| JB | Jerusalem Bible | 1966 |

| NAB | New American Bible | 1970 |

| TLB–CE | The Living Bible Catholic Edition | 1971 |

| NJB | New Jerusalem Bible | 1985 |

| CCB | Christian Community Bible | 1988 |

| NRSV–CE | New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition | 1991 |

| GNT–CE | Good News Translation Catholic Edition5 | 1993 |

| RSV–2CE | Revised Standard Version, Second Catholic Edition | 2006 |

| CTS–NCB | CTS New Catholic Bible | 20076 |

| NCB | New Community Bible | 2008 |

| NABRE | New American Bible Revised Edition | 2011/1986 (OT/NT) |

| NLT-CE | New Living Translation Catholic Edition[11] | 2016 |

| ESV-CE | English Standard Version Catholic Edition[12] | 2018 |

| RNJB | Revised New Jerusalem Bible[13] | 2019 |

| NCB SJ | New Catholic Bible - Saint Joseph Edition | 2019[14] |

1The New Testament was published in 1582, the Old Testament in two volumes, one in 1609, the other in 1610.

2Released in parts between 1913–1935 with copious study and textual notes. The New Testament with condensed notes was released in 1936 as one volume.

3NT released in 1941. The OT contained material from the Challoner Revision until the entire OT was completed in 1969. This Old Testament became the basis for the 1970 NAB

4New Testament only; Gospels by James Kleist, rest by Joseph Lilly.

5Also known as the "Today's English Version"

6The Jerusalem Bible except for the Book of Psalms, which is replaced by the Grail Psalms, and with the word "Yahweh" altered to "the Lord", as directed by the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments for Bibles intended to be used in the liturgy.[15]

In addition to the above Catholic English Bibles, all of which have an imprimatur granted by a Catholic bishop, the authors of the Catholic Public Domain Version[16] of 2009 and the 2013 translation from the Septuagint by Jesuit priest Nicholas King[17] refer to them as Catholic Bibles. These versions have not been granted an imprimatur, but do include the Catholic biblical canon of 73 books.

Differences from Catholic lectionaries

Lectionaries for use in the liturgy differ somewhat in text from the Bible versions on which they are based. Many liturgies, including the Roman, omit some verses in the biblical readings that they use.[18] This sometimes necessitates grammatical alterations or the identification of a person or persons referred to in a remaining verse only by a pronoun, such as "he" or "they".

Another difference concerns the usage of the Tetragrammaton. Yahweh appears in some Bible translations such as the Jerusalem Bible (1966) throughout the Old Testament. Long-standing Jewish and Christian tradition holds that the name is not to be spoken in worship or printed in liturgical texts out of reverence.[15][19] A 2008 letter from the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments explicitly forbids the use of the name in worship texts, stating: "For the translation of the biblical text in modern languages, intended for the liturgical usage of the Church, what is already prescribed by n. 41 of the Instruction Liturgiam authenticam is to be followed; that is, the divine tetragrammaton is to be rendered by the equivalent of Adonai/Kyrios; Lord, Signore, Seigneur, Herr, Señor, etc."[15]

As a result, Bibles used by English-speaking Catholics for study and devotion typically do not match the liturgical texts read during mass, even when based on the same translation. Today, publishers and translators alike are making new efforts to more precisely align the texts of the Lectionary with the various approved translations of the Catholic Bible.

Currently, there is only one lectionary reported to be in use corresponding exactly to an in-print Catholic Bible translation: the Ignatius Press lectionary based on the Revised Standard Version, Second Catholic (or Ignatius) Edition (RSV-2CE) approved for liturgical use in the Antilles[20] and by former Anglicans in the personal ordinariates.[21]

In 2007 the Catholic Truth Society published the "CTS New Catholic Bible," consisting of the original 1966 Jerusalem Bible text revised to match its use in lectionaries throughout most English-speaking countries, in conformity with the directives of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments[15][19] and the Pontifical Biblical Commission.[22] In it, "Yahweh" has been replaced by "the LORD" throughout the Old Testament, and the Psalms have been completely replaced by the 1963 Grail Psalter.

In 2012, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops "announced a plan to revise the New Testament of the New American Bible Revised Edition so a single version can be used for individual prayer, catechesis and liturgy" in the United States.[23] After developing a plan and budget for the revision project, work began in 2013 with the creation of an editorial board made up of five people from the Catholic Biblical Association (CBA). The revision is now underway and, after the necessary approvals from the bishops and the Vatican, is expected to be done around the year 2025.[24]

Differences from other Christian Bibles

Bibles used by Catholics differ in the number and order of books from those typically found in bibles used by Protestants, as Catholic bibles remained unchanged following the Reformation and so retain seven books that were rejected principally by Martin Luther. Its canon of Old Testament texts is somewhat larger than that in translations used by Protestants, which are typically based exclusively on the shorter Hebrew and Aramaic Masoretic Text. On the other hand, its canon, which does not accept all the books that are included in the Septuagint,[25] is shorter than that of some churches of Eastern and Oriental Orthodoxy, which recognize other books as sacred scripture. According to the Greek Orthodox Church, "The translation of the Seventy [the Septuagint] was for the Church the Apostolic Bible, to which both the Lord and His disciples refer. [...] It enjoys divine authority and prestige as the Bible of the indivisible Church of the first eight centuries. It constitutes the Old Testament, the official text of our Orthodox Church and remains the authentic text by which the official translations of the Old Testament of the other sister Orthodox Churches were made; it was the divine instrument of pre-Christ evangelism and was the basis of Orthodox Theology."[26]

The Greek Orthodox Church generally considers Psalm 151 to be part of the Book of Psalms and accepts the "books of the Maccabees" as four in number, but generally places 4 Maccabees in an appendix, along with the Prayer of Manasseh.[27][lower-alpha 1]

The Bible of the Tewahedo Churches differs from the Western and Greek Orthodox Bibles in the order, naming, and chapter/verse division of some of the books. The Ethiopian "narrow" biblical canon includes 81 books altogether: The 27 books of the New Testament; the Old Testament books found in the Septuagint and that are accepted by the Eastern Orthodox (more numerous than the Catholic deuterocanonical books);[lower-alpha 2] and in addition Enoch, Jubilees, 1 Esdras, 2 Esdras, Rest of the Words of Baruch and 3 books of Ethiopian Maccabees (Ethiopian books of Maccabees entirely different in content from the 4 Books of Maccabees of the Eastern Orthodox). A "broader" Ethiopian New Testament canon includes 4 books of "Sinodos" (church practices), 2 "Books of Covenant", "Ethiopic Clement", and "Ethiopic Didascalia" (Apostolic Church-Ordinances). This "broader" canon is sometimes said to include with the Old Testament an 8-part history of the Jews based on the writings of Titus Flavius Josephus, and known as "Pseudo-Josephus" or "Joseph ben Gurion" (Yosēf walda Koryon).[28][29]

See also

- Biblical canon

- Christian biblical canons

- Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

- Council of Trent

- Dei verbum

- Divino afflante Spiritu

- Encyclopaedia Biblica

- International Commission on English in the Liturgy

- Liturgiam authenticam

- Pontifical Biblical Commission

- Protestant Bible

- Second Vatican Council

Notes

- There are differences from Western usage in the naming of some books (see, for instance, Esdras#Naming conventions).

- See Deuterocanonical books#Eastern Orthodoxy

References

- See an Appendix to the Good News Bible, listing quotations in the New Testament from the Old Testament, most of which are from the Septuagint.

- "Code of Canon Law - Book III - The teaching function of the Church (Cann. 822-833)". www.vatican.va.

- Pope Pius XII. "Divino afflante Spiritu, 20–22". Holy See. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- Akin, James. "Uncomfortable Facts About The Douay-Rheims". CatholicCulture.org. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- Knox, Ronald Arbuthnott (1949). On Englishing the Bible. Burns, Oates. p. 1.

- "Scripturarum Thesarurus, Apostolic Constitution, 25 April 1979, John Paul II". Vatican: The Holy See. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- Divino Afflante Spiritu, 16

- Divino Afflante Spiritu, 17

- "Westminster Version - Internet Bible Catalog". bibles.wikidot.com.

- "Francis Aloysius Spencer - Internet Bible Catalog". bibles.wikidot.com.

- "Launch of the new living translation catholic edition". c-b-f.org. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "Bengaluru: Catholic edition of ESV Bible launched". www.daijiworld.com.

- "The Revised New Jerusalem Bible: Study Edition". dltbooks.com. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- https://catholicbookpublishing.com/new-catholic-bible

- Arinze, Francis; Ranjith, Malcolm. "Letter to the Bishops Conferences on The Name of God". Bible Research: Internet Resources for Students of Scripture. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- "Information about the Catholic Public Domain Version of the Sacred Bible". www.sacredbible.org.

- "Nicholas King | News and updates from Nicholas King".

- Booneau, Normand (1998). The Sunday Lectionary. Liturgical Press. pp. 50–±51. ISBN 9780814624579. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- Gilligan, Michael. "Use of Yahweh in Church Songs". American Catholic Press. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- McNamara, Edward. "Which English Translation to Use Abroad". Eternal Word Television Network. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- Burnham, Andrew. "The Liturgy of the Ordinariates: Ordinary, Extraordinary, or Tertium Quid? [PDF]" (PDF). Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Roxanne King (15 October 2008). "No 'Yahweh' in liturgies is no problem for the archdiocese, officials say". Denver Catholic Register. Archdiocese of Denver. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Bauman, MIchelle. "New American Bible to be revised into single translation". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- "NAB New Testament Revision Project". Catholic Biblical Association of America. Archived from the original on 24 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- Pietersma, Albert; Wright, Benjamin G. (2007). A New English Translation of the Septuagint. Oxford University Press. pp. v–vi. ISBN 9780199743971. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Mihăilă, Alexandru (2018). "The Septuagint and the Masoretic Text in the Orthodox Church(es)" (PDF). Review of Ecumenical Studies Sibiu. 10: 35. doi:10.2478/ress-2018-0003.

- McDonald and Sanders' The Canon Debate, Appendix C: Lists and Catalogs of Old Testament Collections, Table C-4: Current Canons of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, page 589=590.

- Cowley, R. W. "The Biblical Canon Of The Ethiopian Orthodox Church Today". www.islamic-awareness.org. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Fathers". Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL).