Infrastructure policy of Donald Trump

The infrastructure policy of Donald Trump includes ensuring U.S. energy independence (by catering to the fossil fuel, nuclear, and renewable energy industry), safeguarding the cybersecurity of the national power grid and other critical infrastructure, locking China out of the U.S. fifth-generation Internet market, and rolling back regulations to ease the process of planning and construction. While there have been no major infrastructure spending packages yet, some individual policies and projects have advanced piecemeal, especially in rural areas.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Incumbent

Presidential campaigns Controversies involving Russia Business and personal  |

||

Although there is recognition of the need to upgrade American infrastructure from both sides of the political aisle, as of April 2020, no major infrastructure bill has been passed due to disagreements over the details of such a spending package, namely, what to spend on, how much to spend, and how to pay for it. 'Infrastructure' is a rather broad term that means different things to different people. In general, the aim of the Trump administration is revitalizing the national economy and enhancing national security despite the tendency of his own Republican Party to oppose large federal expenditures and tax hikes whereas members of the opposition Democratic Party typically favor investing in renewable energy and new infrastructure that could combat climate change, and tend to be less averse to deficit spending.

This article focuses exclusively on physical or hard infrastructure, as opposed to soft infrastructure, or public institutions.

Views, vision, and standards

Infrastructure development is a priority of the Donald Trump administration. He considers the modernization of American infrastructure as an extension of his career as a real estate developer and a concrete item to add to his legacy as President.[1] He also views infrastructure investments as a tool to create jobs and to spur economic growth.[2] In this 2015 book Crippled America, he cites the Senate Budget Committee estimate that "rebuilding America will create 13 million jobs."[2] As early as May 2015, one month before launching his presidential campaign, Donald Trump expressed his desire to "fix" America's aging infrastructure,[1] making it "second to none."[3] He expressed concern about the state of American infrastructure on multiple occasions, drawing comparisons with other countries. For example, he stated that American passenger trains were slow compared to those in China and American airports to be dirty and dilapidated next to their counterparts from China, Saudi Arabia, or Qatar.[2][4] He acknowledged that modernizing American infrastructure was going to be expensive but argued that in the end, such an investment would pay for itself. In this regard, his position is in line with that of the Democratic Party. President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden had themselves been advocating for more federal infrastructure spending.[2]

Extensive infrastructure spending is a key part of Trump's nationalist and populist economic platform, which also includes opposition to free trade, support for tariffs, and the repatriation of American jobs. This is unusual in the modern Republican Party, which typically endorses free-market or neoliberal economics.[5] According to political scientists Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin, while working-class voters have been leaving the Democratic Party since the 1960s, the popularity of Trump's economic platform suggests there have been sizeable pockets of voters mainstream Republicans failed to reach. However, according to economist Robert Reich, the fact that Trump appears more interested in marketing his brand name rather than pursuing public policy hampers his chances of success.[6]

On January 31, 2019, Trump issued an executive order encouraging the purchase of U.S.-made construction materials for public infrastructure projects, especially those that need funding from the federal government.[7] This followed his 2017 "Buy American, Hire American" executive order restricting the hiring of foreign workers and tightening standards for federal acquisitions. As of February 2019, Canadian officials were negotiating an exemption for their country.[8]

Environmental reviews of infrastructure projects

In April 2019, President Trump signed two executive orders intended to accelerate energy infrastructure projects. The first makes it harder for oil pipelines and other energy projects to be delayed due to environmental concerns. The second modernizes the approval process for projects crossing international borders. Speaking in front of union workers from the energy industry, the President stated that blocking energy projects "does not just hurt families and workers like you, it undermines our independence and national security."[9]

In early January 2020, the Trump administration announced revisions of the 50-year-old National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) that would relax environmental regulations on infrastructure constructions in order to speed them up.[10] Federal agencies would no longer have to take climate change into account when assessing major infrastructure projects and would have to complete their comprehensive environmental reviews in two years. Infrastructure projects that require federal permits but little federal funding are exempt from such reviews. Nor would new projects have to account for "cumulative" effects. In the twenty-first century, this means investigating the effects of greenhouse gas emissions and sea level rise, among other things. In addition, instead of applying for permits from each relevant government agency, only one decision from the government would be necessary. Signed into law in 1970 by President Richard Nixon, NEPA requires the federal government to analyze the environmental impacts of a given infrastructure project in detail. Due to its wide scope, both supporters and opponents believe this is one of the most litigated laws in the United States.[11][12][13] NEPA was drafted in response to a 1969 oil spill off Santa Barbara, California, that sparked public outcry, and other instances of air, land, and water pollution.[14] Before 2020, there was only one major change. In 1983, it was decided that the use of worse-case scenarios should be limited.[11]

On the fiftieth anniversary of NEPA, President Trump wrote, "The environmental review process designed to improve decision-making has become increasingly complex and difficult to navigate" because of the "significant uncertainty and delays that can increase costs, derail important projects, and threaten jobs for American workers and labor union members." Trump asserted that the revisions would "benefit our economy and environment." In fact, construction workers' unions have long argued that NEPA has been a burden on energy and public transportation projects.[11] Although the opponents of these proposed revisions were worried that they would make it easier for the oil and gas industry to build new pipelines, the Trump administration focused on schools and highways, which were probably of greater interest to the American people.[12] If the proposed revisions survived their legal challenges, environmental activists would no longer be able to halt pipeline construction by litigation, a key tool they have been using since the middle of the Obama administration.[11][12] While there have been examples of bureaucracy being burdensome on building projects in the past, such a drastic change would likely invite even more lawsuits.[12]

After 60 days of public hearing, a final regulation can be expected, probably before the 2020 Presidential election.[11][12]

Background: State of American infrastructure (2015–2019)

Every four years, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) assembles a panel of civil engineers to analyze government data on aviation, bridges, roads, transit, dams, levees, parks, schools, solid waste, drinking water, and waste water.[15] In its 2017 report, the Society gave American infrastructure an overall grade of D+ and recommended a $2 trillion increase in funding for infrastructure over a decade,[16] half of which for surface transportation, which includes public transit, roads, bridges, and rail.[15] However, in the World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Competitiveness Report for 2016-17 the overall quality of American infrastructure jumped from 25th to 12th place out of 138 countries considered.[17] U.S. infrastructure ranked ninth in the 2017-18 report. Infrastructure is one of the "pillars" of the WEF Global Competitiveness Index.[18] Nevertheless, while the U.S. has some of the most resilient infrastructure systems in the world, the situation is deteriorating with time as they are aging and increasingly vulnerable to disruptive events. U.S. infrastructure was built according to standards introduced 50 years ago, and these have become insufficient because of today's more frequent extreme weather events.[17]

.jpg)

Moreover, current U.S. infrastructure practices do not do a good job of promoting environmental sustainability. Carbon-dioxide emissions per capita is higher than that of other industrialized countries, such as France, whose level is three times lower.[17] Some three quarters of American commuters travel by cars as public transit is not as reliable as it is in other developed countries. American railroads are generally reserved for freight.[17] Indeed, this is reflected in the 2017 ASCE report, which gave American rail the highest score in all 16 categories; however, the score is brought down because of the quality of U.S. public transit.[15] Moreover, the quality and amount of rail per capita is low compared to other developed countries. This reflects the fact that rail is infrequently used for intercity travel in the United States.[19] By contrast, in Europe, most freight is moved through waterways, which is considered more fuel-efficient and cost-effective, while railroads are generally reserved for passenger traffic. The U.S. ranks second in road infrastructure spending, but only 60th in safety due to the high rates of traffic fatalities.[17] On top of that, an average American loses 100 hours each year in traffic congestion.[3] According to the data research firm INRIX, the five American cities with the worst traffic in 2018, measured by the average number of hours lost to congestion per driver, were Boston (164), Washington D.C. (155), Chicago (138), Seattle (138), and New York City (133).[20] However, between 2007 and 2012, there was a surge in spending on mass transit.[21] State and local voters are increasingly willing to tax themselves.[22] In the 2018 midterm elections, voters approved an overwhelming majority transit initiatives at the ballot box.[23] For example, residents of Michigan voted to legalize cannabis and to impose an excise tax on it in order to fund the state's transportation needs.[22] According to the ASCE, Michigan and New York have the worst roads in the nation.[24] Like the ASCE, consulting firm Oxford Economics identified a significant gap between current and needed U.S. spending on road infrastructure, roughly 50%.[19]

Representative Peter DeFazio, chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, stated that the United States needs to spend at least $2 trillion on its infrastructure, including 140,000 bridges and 40% of highways that are in a state of poor repair.[25] According to a 2019 report from the American Road and Transportation Builders Association (ARTBA), four out of ten structures need to be rehabilitated. In particular, 47,000 bridges are "structurally deficient," meaning they need to be renovated but are still safe to cross. That number is down 7,000 from 2017, but only because the Federal Road Administration changed its standards on what it means for a bridge to be deficient.[26]

About 70% of the 90,580 dams will be over half a century old by 2025, more than the average lifespan of dams.[17] While legislation typically address repairs and rehabilitation, many dangerous dams have been removed. According to the Association of Dam Safety Officials (ADSO), there were 2,000 state-regulated "high-hazard" dams in 2015. A dam is categorized as such if failure likely results in death. The ADSO also estimated that some $60 billion was needed to renovate dams in a state of poor repairs, one third of which is for high-hazard dams.[27]

Some 21 million Americans have to put up with unsafe drinking water each year. In 2019, floods broke through hundreds of miles of levees in the Midwest and wiped out millions of acres of crops.[3] Local water utilities have struggled to keep up with much needed capital improvement projects on one hand and regular repairs and maintenance on the other.[21]

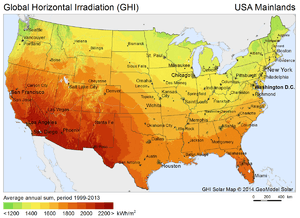

Since the 1980s, the number of power outages due to weather events have increased tenfold.[17] Even though many parts of the United States, such as Texas, have seen a renewable-energy boom, transmitting the power generated to the large cities when they are needed most has proved troublesome due to opposition from farmers and other landowners who see high-voltage power cables as eyesores with little benefits for them.[28]

According to the Federal Communications Commission, some 24 million of Americans still do not have access to broadband Internet.[24][note 1]

Many American public schools suffer from poor ventilation, heating, and plumbing. Some schools even leak when it rains. The ASCE gave them a score of D+.[24]

Businesses and communities are concerned over the state of American infrastructure and the inability of Congress to fund a comprehensive modernization program.[16] While federal, state, and local governments have been spending more on infrastructure repairs and maintenance in nominal terms, their actual purchasing power has been reduced because of the rising costs of construction materials. For that reason, amounts spent have fallen in real terms, despite a bump thanks to the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) following the Great Recession of 2007-8. Repairs and maintenance expenditures steadily climb while less money goes to capital projects. This trend has existed since the mid-1950s, but the decade following the Great Recession saw its intensification.[21]

Between 2010 and 2015, the United States spent an average of 2.5% of its GDP on infrastructure. For comparison, this number was 2.1% for the United Kingdom and Germany, 8.3% for China, and 5.6% for India.[29] According to the Global Infrastructure Outlook of Oxford Economics, the United States will likely spend $8.5 trillion on infrastructure between 2016 and 2040. However, they estimated that it needs to spend $12.5 trillion, or about half a trillion per year, in the same period. Figures are in 2015 dollars.[19]

Funding efforts

2017-19

Trump presented an infrastructure plan to Congress in February 2018, with $200 billion in federal funding and $1.5 trillion from the private sector. Democrats opposed this plan because of its emphasis on state and local funding and private investments. Lawmakers from both sides of the aisle also questioned where the money would come from.[30] By September 2019, as signs of a possible recession appear over the horizon, Donald Trump could use, among other things, infrastructure spending to tackle the problem like his predecessors did, albeit at the cost of more public debt as tax hikes are generally unpopular.[31] However, because interest rates are low, public debt is not as troublesome, especially if additional debt is used to finance investments that could boost growth, such as in infrastructure.[32]

More infrastructure spending was Trump's most popular promise in his presidential campaign, with approval from two thirds of Americans. In his first speech as President-elect, Trump vowed to "begin the urgent task of rebuilding" the United States of America.[3] In his 2019 State of the Union address, Trump once again called for investments in infrastructure, but offered very few specifics. Moreover, his vision made little headway because despite bipartisan agreement that American infrastructure is in a state poor repair and needs upgrading, members of Congress have not been able to reach a consensus on how to pay for it.[33] The problem of aging infrastructure cannot be addressed by the individual states because the costs are too high, meaning the federal government has to be involved.[34] The federal tax on fuels, a major source of revenue for infrastructure spending, remains the same as it was in 1993,[16] at $0.183 per gallon ($0.048 per liter).[35] In addition, the Highway Trust Fund is losing its effectiveness thanks to improving energy efficiency and the arrival of alternative-fuel vehicles whose owners do not have to pay the gas tax.[35] Although people who attended a meeting with Trump in February 2018 suggested that the President was open to the idea of raising the gas tax to $0.25 per gallon ($0.066 per liter),[35] the White House downplayed possibilities of such a tax hike.[1] According to the Chamber of Commerce, which backs the proposal, it would generate about $375 billion over ten years.[35]

President Trump held a meeting with top Democrats in Congress, Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer, on April 30, 2019, but failed to strike a deal. He wanted Congress to first pass the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), the newly negotiated version of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA),[36] to stop investigating him[37] and to remove the threat of impeachment.[38] He also wanted a package with automatic re-authorization of highway and transit funding rather than a broader plan with money for a variety of items from hospitals to broadband Internet.[36]

2020

While Republicans have generally been skeptical of Democrats' proposals to finance massive infrastructure programs by debt, in late March 2020, as lawmakers ponder how to alleviate the severe economic downturn induced by the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, they seem to have coalesced around the need to upgrade American infrastructure and create jobs. President Trump publicly endorsed this possible deal as the next phase of the federal response to the pandemic. Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin told CNBC the President would like to take advantage of low interest rates to finance this potential bill. The Democrats' infrastructure plan includes funds for passenger rail transportation – with money for Amtrak's stations and services –, ports and harbors, climate-change resiliency, greenhouse gas emissions reduction, and expanding access to broadband Internet. A different plan passed the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee unanimously in July 2019; it would allocate $287 billion over five years, $259 billion of which to maintain and repair roads and bridges. President Trump mentioned this second plan in his 2020 State of the Union Address.[39]

Trump indicated he would like to go further than this Senate plan. In late March, he voiced his support for a potential "Phase 4" stimulus package worth two trillion dollars of infrastructure spending. He called it "Phase 4" because there were previously three stimulus bills aimed at mitigating the effects of the pandemic. Earlier in the year, Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin discussed a possible infrastructure plans with House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Richard E. Neal, but their talks were derailed as the pandemic continued to spread across the United States. In order for such a spending package to be passed, lawmakers from across the political spectrum would need to be able to overcome long-standing disputes over what to spend on, how much money to spend, and where the money comes from, because the term 'infrastructure' is quite broad and means different things specifically to different people.[40] Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (Kentucky) and House Minority Leader Keven McCarthy (California) both expressed skepticism of the need for a fourth stimulus package in a row, saying that would like to wait and see the effects of the first three packages first.[41]

Disaster relief

In early June 2019, President Trump signed a disaster relief and recovery bill worth $19 billion. The Additional Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Act of 2019 includes $3 billion for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to repair damages inflicted by natural disasters in the previous three years and to invest in resiliency and flood protection, unlocks $8.9 billion in disaster relief for Puerto Rico and offers an additional $900 million to help the territory recover from Hurricane Maria. This bill also provides additional resources to the U.S. Forest Service for wildfire suppression activities. Some $1.6 billion is allocated to repairing roads and bridges post-disaster through the Federal Highway Administration's Emergency Relief Fund.[42]

The Act also provides financial assistance to the U.S. Marine Corps base Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, which sustained $3 billion worth of damages by Hurricane Florence.[42]

Energy

Electrical power grid

In late June 2017, about a week after cybersecurity experts realized that a piece of malware used to attack Ukraine's power grid the previous year could, with modifications, be used against the United States, President Trump met with cabinet officials, leaders from the energy sector, cybersecurity experts to discuss the threat. The federal government identifies energy infrastructure, mostly owned and operated by the private sector, as critical, and the Department of Homeland Security cooperates with the private sector to ensure its security. Using an executive order issued in May 2017, President Trump ordered, among other things, an investigation on America's preparedness against a cyber attack resulting in prolonged power outages.[43]

As a consequence of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, utility companies found themselves with considerable amounts of extra money in 2018. This means they could spend it on infrastructure upgrades and retraining displaced workers (from coal and nuclear power plants) without having to pass the cost onto consumers or requesting financial assistance from the government. According to the International Energy Agency, the United States needs to spend $2.1 trillion between 2014 and 2035 so that its grid can smoothly accommodate wind and solar power.[44]

In early 2020, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) published a paper on the threats posed by geomagnetic storms to the nation's power grid. This research follows from President Trump's Executive Order 13865 on Coordinating National Resilience to Electromagnetic Pulses from March 2019. Such storms are caused by the interaction between solar winds and the Earth's magnetic field. Resultant magnetic perturbations generate electric fields,[note 2] which could disrupt ground-based electrical power grids. While geomagnetic storms do not occur that often, when sufficiently strong they can cause considerable damage. For example, the magnetic storm of 1921 set the telegraphic stations used by rail companies in New York ablaze. Those comparable to the Solar Storm of 1859 pose an even greater threat. A study from the National Academy of Sciences suggests that if one were to occur in the twenty-first century, its economic damage could be as high as two trillion dollars. Due to the electrical properties of the rocks, the most vulnerable areas are in the Northern Midwestern and Northeastern United States, especially the Piedmont formation, located east of the Appalachian Mountains, near some of the largest of American cities.[45]

In late April 2020, President Trump signed an executive order aimed at protecting the U.S. national power grid against foreign cyber attacks. "A successful attack on our bulk-power system would present significant risks to our economy, human health and safety, and would render the United States less capable of acting in defense of itself and its allies," he wrote.[46] This executive order bans the purchase and installation of equipment manufactured outside the United States.[47] In addition, it tasks the Secretary of Energy, Dan Brouillette at the time of its issuing, with creating a list of safe vendors, identifying any vulnerable components of the grid and replacing them. In 2018, then Secretary of Energy Rick Perry created the Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response (CESER) to combat cybersecurity threats to the U.S. power supply.[46] While the U.S. has not witnessed any destructive cyber attacks on its power grid yet, foreign actors have conducted reconnaissance operations on this infrastructure. In January 2020, the FBI notified grid operators about the vulnerabilities in their software supply chain.[47]

Energy independence

President Donald Trump's position with regards to energy independence is similar to that of his predecessors dating back to the 1970s.[48] His Energy Secretary, Rick Perry, argued that "An energy dominant America means self-reliant. It means a secure nation, free from the geopolitical turmoil of other nations who seek to use energy as an economic weapon."[49] In 1960, the world's leading oil exporters – Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela – joined forces to create the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in order control global oil prices, though they failed to achieve this objective until 1973. In October 1973, a brief but bloody and inconclusive war broke out between Israel and the Arab states. The Soviet Union and the United States helped secure a truce, but in an attempt to force the West to pressure Israel to withdraw from the territories it held since the Six Days War of 1967, the Arab nations stopped selling oil to Western Europe, the United States, and Japan, causing a severe worldwide energy shortage. Previously, from the mid-nineteenth century up until right after World War II, the United States produced far more oil than it consumed. However, after the War, the number of American car owners ballooned, while oil was used to manufacture plastics, pesticides, fertilizers, among many other products. Oil and natural gas became quite popular for residential heating. At the eve of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, the United States was importing one third of the oil it consumed. Although the Arab world lifted their oil embargo on the industrialized world after Secretary of State Henry Kissinger managed to persuade Israel to withdraw from some of the territories it seized in the 1967 war, they announced that the price of oil was going up to $11.65 a barrel. It was $3.00 on the eve of the 1973 war.[50] President Jimmy Carter introduced a plan to conserve energy and reduce U.S. dependence on foreign oil, which included a tax on gasoline, and on the "gas guzzlers," or cars that were particularly energy-inefficient.[51] Conservation, coupled with increased production from countries outside of OPEC, such as Mexico, Norway, and the United Kingdom, helped gradually reduce the price of oil in the 1980s.[52]

U.S. oil production has been steadily rising since 2009 while natural gas production increased 50% between 2005 and 2015, and then by 11% by 2018. Affordable and widely available energy resources have benefited manufacturers and consumers alike.[53] In 2015, President Barack Obama, Trump's immediate predecessor, lifted a 40-year old ban on oil exports and granted over two dozen liquefied-natural-gas-export licenses.[49][48] Trump's goal is to achieve "energy dominance," or the maximization of the production of fossil fuels for domestic use and for exports.[54] In addition, the Trump administration seeks to export American know-how in coal, natural gas, and new nuclear reactor technology.[55]

Shortly after taking office in 2017, President Donald Trump announced the U.S. was withdrawing from the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, thereby fulfilling a campaign promise.[56] He said he wanted a "fair" deal that would not undermine U.S. workers and businesses,[57] or compromise U.S. national sovereignty.[58] Proponents of the agreement argue, however, that backing out will result in a loss for the U.S. national economy as new green jobs are offered instead to competitors overseas.[58] President Trump replaced contents related to climate change from the Obama administration on the White House website with his official energy policy. One focus was to slash "burdensome regulations on our energy industry."[59] Trump also announced his attempts to reach a negotiation with leaders involved in the agreement. But they said accord was "non-negotiable."[58] President Trump announced the formal United States withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on June 1, 2017.[60] He has also been rolling back Obama-era environmental regulations ever since,[57] including the Clean Power Plan.[61]

As of 2016, the United States had 264 billion barrels of oil in reserve, the largest amount of any nation.[62] It also has a vast amount of coal reserves, amounting to 26% of the world's total, more than any other nation.[63]

Fossil fuels

In January 2017, President Trump signed an executive order reviving the Dakota Access Pipeline, bringing oil from shale reserves in North Dakota to refineries in Illinois along a route 1,172 miles (1,887 km) long. He insisted that American-made construction materials be used to create high-skilled jobs. TransCanada, which owns the project, originally planned to use 65% of materials from the U.S. and the rest from Canada. This decision received support from the oil industry, which considered it long overdue. Opponents include Native American tribes who argued it could jeopardize their water supply, cause flooding, and disturb religiously important sites. Although President Obama rejected it, polls conducted jointly by The Washington Post and ABC News found that a clear majority of Americans, 55%, approved the project, expecting it to create plenty of jobs, while only 34% disapproved. However, they were divided on the question of environmental risk.[64] The Pipeline was completed by April 2017, and made its first oil delivery the following month. Philadelphia Energy Solutions, the largest oil refiner on the U.S. East Coast, stopped taking delivery by rail in June.[65]

In March 2017, the Trump administration approved the construction of the Keystone XL Pipeline, reversing a decision by the Obama administration and fulfilling a campaign promise.[66] This pipeline would bring 830,000 barrels of oil, equivalent to 35 million gallons or 132,490 cubic meters, from the tar sands of Alberta, Canada, across the U.S. states of Montana, South Dakota, and Nebraska, before connecting to existing pipelines carrying crude oil to U.S. refineries. (See map on the right.)[67] This project sparked intense opposition from environmental activists who argue that extracting oil from the oil sands produces 19% more greenhouse gases than traditional methods of crude oil extraction. The pipeline would also run across the Ogallala Aquifer, one of the world's largest underground deposits of fresh water. According to a 2015 State Department report, this project would create 42,000 jobs directly and indirectly, including 3,900 construction jobs if the pipeline was built in a year, and 50 permanent jobs to maintain the pipeline.[66] This project has been held up the courts. A U.S. District Court for Montana judge blocked the project in November 2018, arguing that the State Department failed to assess the cumulative effects of greenhouse gas emissions and the impact on Native American land resources. In March 2019, the President signed a new permit in order to circumvent the Montana court decision.[54] In June 2019, a three-judge panel from the U.S. 9th District Court of Appeals lifted the injunction that blocked the pipeline's construction and dismissed a lawsuit by environmental and Native American groups. The appellate judges also agreed with the Justice Department that Trump's new permit nullified the legal challenge on environmental grounds.[67] But this second permit was legally challenged by Native American groups as of October 2019.[68]

In January 2018, the Interior Department announced plans to allow drilling in nearly all U.S. waters. This would be the largest expansion of offshore oil and gas leasing ever proposed, and includes regions that were long off-limits to development and more than 100 million acres in the Arctic and the Eastern Seaboard, regions that President Obama had placed under a drilling moratorium.[69]

In late May 2019, the Department of Energy rebranded natural gas as "molecules of freedom" which it sought to export worldwide. The announcement was made during the expansion of a facility in Quintana Island, Texas, that produces liquefied natural gas. This expansion is expected to bring 3,000 jobs to the area.[57] In general, there is no difference between the export policy of the Trump administration for liquefied natural gas and that of the Obama administration.[49]

At an event in Salt Lake City, Utah, Energy Secretary Rick Perry announced that the Trump administration is committed to making fossil fuels cleaner rather than imposing "draconian" regulations on them. He said the administration wanted to invest in the research of development of ways to reduce emissions as demand for coal drops and that for natural gas rises.[70] Perry pointed to efforts already underway to replace old and inefficient coal power plants and to use more liquefied natural gas.[71] According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), U.S. emissions fell by 13% between 2005 and 2017.[70]

_(cropped)_.png)

In June 2019, the Trump administration introduced a new rule on coal power plants' emissions, requiring electric utilities to cut their emissions to 35% below 2005 levels by 2030. It authorizes the setting up of targets for improving efficiency by state regulators and does not require switching from coal to other energy sources. This new rule replaces the Obama-era Clean Power Plan, which established specific carbon-emissions reduction target for each state. However, according to the International Energy Agency, the U.S. electricity sector would need to reduce its emissions by 74% below 2005 levels over the same period in order to prevent the global average temperature from rising by more than 2 °C. Nevertheless, utilities are already moving away from coal as the costs of alternatives become increasingly competitive.[72]

The oil and gas industry has been growing rapidly, thanks to Trump's support for drilling both offshore and on public lands, as well as advances in hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, technology.[73] This method of extraction involves pumping a mixture of water, sand, and some chemicals into the Earth to separate oil from rocks, and "horizontal drilling," meaning digging a hole through layers of shale rocks, then changing direction at 90°. Fracking technology has been around for years, but recently, companies have been able to improve its speed and efficiency.[74] Domestic consumption of natural gas jumped 10% in 2018, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA).[70] In the past, the U.S. was the world's largest oil importer and prohibited oil exports; in 2018, it became one of the leading suppliers of light crude oil to Europe, behind only Russia and Iraq. The United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Italy are the top customers, importing almost seven eighths of U.S. exports to Europe. The U.S. could potentially replace Russia, the Middle East, and Africa as Asia's top supplier as well. Demand for U.S. light oil is expected to rise in the years ahead due to tightened marine fuel regulations.[75] As of 2018, the U.S. is the world's largest exporter of oil and (liquefied) natural gas.[73] In November that year, U.S. oil exports exceeded imports for the first time since 1973.[76] Therefore, Trump has fulfilled his promise of promoting fossil fuels.[73] In June 2019, demand for U.S. oil surged as attacks on oil tankers passing through the Strait of Hormuz disturbed buyers.[77] He urged countries that depended on Middle Eastern oil to protect their own ships on a "dangerous journey," specifying China and Japan.[77]

The Trump administration is selling leases in Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil companies for drilling. Although environmentalists oppose the project, saying that it damages the landscape and harms the caribou and birds that migrate there, some native Alaskans living in the area support the move. While infrastructure there is rather limited, residents receive their paychecks from the oil industry drilling in Prudhoe Bay, which also pays for a full-time fire department and a basketball gym. They also have flush toilets, which do not exist in villages outside the Refuge. However, after a lease sale, an oil company will need to first drill some test wells to see if there is a significant amount of oil in the area, and if they find it, they need environmental reviews and permits before they can extract it.[78]

Cheap and abundant energy has fueled the revival of American manufacturing. However, steel tariffs from the China–United States trade war also increased the cost of pipeline construction and other equipment.[53]

Nuclear energy

In 2017, President Trump announced his administration was launching a "complete review" of ways to revive and expand the nuclear power industry.[48] Energy Secretary Rick Perry also noted the importance increasing the use of nuclear energy,[71] calling it "a very important part" of the Trump administration's all-of-the-above energy strategy.[79] As of 2017, nuclear reactors generate about one fifth of U.S. electricity, but this market share could fall to 11% by 2050 as the nation's aging nuclear power plants retire[48] and because of competition from natural gas and renewable sources.[79] The potential loss of such a large chunk of the nation's zero-emissions electricity generation is a cause for concern, especially as the financial viability of large-scale nuclear power projects has come into question. Perry said his Department was looking into small modular nuclear reactors, which can be put together to produce up to a quarter of the power a typical nuclear reactor generates.[79] As of 2019, there were about two dozens potentially viable modular reactor designs trying to enter the market. The U.S. also looks to export next-generation reactor technology overseas and compete with China and Russia.[80]

Inconsistent government support and unfavorable bureaucracy and logistics have made research and development in civilian nuclear power difficult.[79] As of 2019, the average age of U.S. nuclear power stations is 39 years old.[81]

Renewable energy

Background

The Trump administration generally prefers fossil fuels to renewable energy.[82] In fact, Trump has made his support for the coal industry clear, so much so that his electoral victory in 2016 was celebrated by the coal mining community.[83] Nevertheless, demand for solar and wind energy continues to grow thanks to falling costs.[82] At the same time, the percentage of U.S. electricity generated by coal power plants has fallen due to strong competition from natural gas, wind, and solar power.[73] While the traditional fossil fuel industry employed 187,000 jobs in 2016, the wind power industry grew by nearly 32% to 102,000 people. Meanwhile, the solar power industry grew by almost a quarter to 374,000 jobs. In 2017, solar and wind together generated 10% of U.S. electricity.[61] As of 2018, fossil fuels satisfy 80% of U.S. energy demand, according to the EIA.[70] In any case, the Trump administration has implemented policies that turned out to be favorable for the renewable energy industry.[84]

According to a 2019 CBS News poll on 2,143 U.S. residents, 42% of American adults under 45 years old thought that the U.S. could realistically transition to 100% renewable energy by 2050 while 29% deemed it unrealistic and 29% were unsure. Those numbers for older Americans are 34%, 40%, and 25%, respectively. Differences in opinion might be due to education as younger Americans are more likely to have been taught about climate change in schools than their elders.[85] As of 2019, only 17% of electricity in the U.S. is generated from renewable energy, of which, 7% is from hydroelectric dams, 6% from wind turbines, and 1% solar panels. The intermittency of wind and solar power poses the issue of storage, and there are no rivers for new dams.[81]

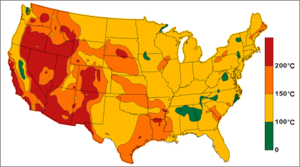

Geothermal

Ever since President Trump took office, the Department of Energy has provided funding for the research and development of new ways to harness geothermal energy. In December 2017, the Department's Geothermal Technologies Office began its program to look for cheaper methods of drilling, which account for half the cost of a geothermal power project.[86] A report released in late May 2019 by the Department of Energy suggests that U.S. geothermal power capacity could increase by more than twenty-six times by 2050, reaching a total installed capacity of 60 GW, thanks to accelerated technological development and adoption. (Also see figure on the left.) The report also demonstrates the benefits of geothermal power for residential and industrial heating.[87] Energy Secretary Rick Perry announced his Department had provided funding for a $140-million research facility at the University of Utah on man-made geothermal energy.[71]

In accordance with President Trump's desire for further energy developments in the deserts of California, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) announced in January 2020 it wanted to scale back the amounts of land set aside for conservation, arguing that the footprint of geothermal power plants is compact compared to other types. Some 22,000 acres (89 square kilometers) of land in the southern Owens Valley, what BLM called the Haiwee Geothermal Leasing Area, would be available for lease to geothermal energy projects. The Bureau estimated that this area, with its dormant volcanoes and lava beds, has the potential to spur a billion dollars in investments and to provide 117,000 homes with electricity. Previously, the President ordered BLM to reconsider its Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan in order to expand the amounts of land available for renewable energy and mining projects. This decision attracted praise from the advocates of green energy who argue that the environmental impact of such projects is exaggerated and criticism from conservationists who prefer the Obama-era policy, pointing to the existence of some rare species in the area.[88]

Hydro

In November 2017, the Northern Pass transmission line project, proposed by utilities company Eversource to carry hydroelectricity from Quebec to New England, received a presidential permit. For years, New England has been shedding its coal power plants, and the process continues under President Trump.[89] However, in July 2019, the New Hampshire Supreme Court unanimously upheld the state's Site Evaluation Committee rejection, citing concerns over the land use, environmental and economic impacts of the 192-mile (307-km) transmission line.[90]

In January 2018, President Trump said he would like the United States to harness more hydropower. However, it is not clear whether he would like to increase hydropower generation or he was unaware of how much hydroelectric dams contribute to the national grid. In any case, while the Energy Information Administration does not expect U.S. hydroelectricity generation to increase in the upcoming years, it is possible to upgrade the turbines of existing facilities as the average U.S. hydroelectric unit has been operating for 64 years. In addition, most dams in the U.S. are not for power generation, but can be fitted with turbines.[91]

Solar

Even though President Trump holds critical views of renewable energy in general and solar in particular, his appointees in the Department of the Interior have been facilitating the development of multiple renewable energy projects in public lands.[92] In May 2020, the Trump administration gave final approval to the Gemini Solar Farm project in Nevada. Worth a billion dollars, it includes 690 MW of power-generating capacity and 380 MW of four-hour lithium-ion batteries. It is enough to power 260,000 households and offset the greenhouse-gas emissions of 86,000 cars. Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt said it would also create 2,000 jobs, directly and indirectly, and pump $712.5 million into the economy. Gemini, scheduled to enter service by the end of 2023, is the largest solar farm project ever approved in the United States and one of the largest in the world. Opponents argued that the project puts a number of endangered species, such as the Mojave desert tortoise, at risk.[92][93] Previously, two solar farms on public lands were approved: the Sweetwater Project (80 MW) in Wyoming and the Palen Project (500 MW) in California.[92]

In 2018, as part of the ongoing trade war between the U.S. and China, Trump imposed tariffs on imported solar cells.[94] The push for tariffs to protect American manufacturing and jobs in the solar power industry began in April 2017, when a bankrupt Georgia-based solar cell maker filed a trade complaint that a flood of cheap imports put them at a severe disadvantage. In response, the President imposed 30% tariffs of solar imports in January 2018.[95] The solar industry is currently one of the fastest growing in the United States, employing more than 250,000 people as of 2018.[94] On one hand, these tariffs forced the cancellation or scaling down of many projects and restrict the ability of companies to recruit more workers.[94] On the other hand, they have the intended effect of incentivizing domestic manufacturing. Many solar power companies are transitioning towards automation and consequently will become less dependent on imports, especially from China.[94] Analysts believe Trump's tariffs have made a clear impact. Without them, the manufacturing capacity for solar cells in the United States would likely not have increased significantly, from 1.8 gigawatts in 2017 to at least 3.4 gigawatts in 2018, they argue. However, because of the increasing reliance on automation, not that many new jobs will be created, while profits will flow to other countries, as many firms are foreign.[95] By 2019, the solar power industry has recovered from the initial setbacks due to Trump's tariffs, thanks to initiatives from various states, such as California.[96] Moreover, it is receiving considerable support from the Department of Energy. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) launched the "American-made Solar Prize" competition in June 2018 and has handed out tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash prizes for the most promising solar cell designs.[97] Prices of solar cells continue to decline.[95] At the same time, the cost of installation has fallen by 70% between 2009 and 2019. Solar power can now go head to head against even natural gas. (A federal tax credit from 2006 has also been helpful.) Thanks to economic forces, the United States is now the second largest market for solar power, after China, and utility-scale projects are booming across the American Southeast.[98]

Wind

Despite Trump's fondness for coal, his administration is not entirely hostile to renewable energy. Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke wrote in an op-ed for the Boston Globe that he wanted to provide "an equal opportunity for all sources of responsible energy development, from fossil fuels to the full range of renewables." He added that "wind energy — particularly offshore wind — will play a greater role in sustaining American energy dominance." Zinke wanted to assist developers by allowing them to postpone decisions on detailed designs during the planning process so that they could take advantage of newer technologies. Offshore wind power is steadily picking up steam in the United States with numerous projects being pursued on both coasts of the country.[99] As of June 2019, there is only one operational offshore wind farm in the United States, the Block Island Wind Farm, located near the coast of Rhode Island. Some experts estimate that the entire East Coast could be powered by offshore wind farms.[100] Meanwhile, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, the contiguous United States has the potential for 10,459 GW of onshore wind power.[101][102] The capacity could generate 37 petawatt-hours annually, an amount nine times larger than current total U.S. electricity consumption.[103] There are also substantial wind resources in Alaska,[104] and Hawaii.[105]

Priority energy infrastructure projects

This list is taken from the top ten civil engineering projects that pertain to energy. They are all public-private partnerships.[106]

- Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Wind Energy Project, Wyoming, $5 billion. The Power Company of Wyoming will install some 1,000 wind turbines in the south of their state over an area of 2,000 acres (8.1 square kilometers) that will generate up to 3 GW of power.[106] It received key federal permits in early 2017[107] and is expected to be completed by 2026,[108] when it will become the largest wind farm in the U.S.[107] There will be a transmission line to serve California, which will help that state achieve its renewable energy target by 2030.[107]

- Atlantic Coast Pipeline, up to $5 billion. This pipeline would carry natural gas over 609 miles (980 km) from West Virginia to North Carolina, with an outward curve near the coast of Norfolk, Virginia.[106] Construction of the pipeline began in West Virginia on May 23, 2018,[109] but stopped in December that year due to lawsuits. Its estimated completion date changed from late 2019 to late 2021, but it may never be completed unless the United States Supreme Court overrules the decision from a lower court.[68]

- Hydroelectric plants operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, $4 billion. At present, the Corps operates plants with an average efficiency of just 80%, well below the industry average of 99%, because its turbines are over 50 years old. This scheme will upgrade existing facilities.[106]

Federal public buildings

In February 2020, President Trump proposed an executive order mandating "classical" architecture—including Gothic, Romanesque, Spanish, Mediterranean and other traditional styles—for all federal public buildings in the District of Columbia. Trump and the National Civic Art Society, which was a driving force behind the proposed executive order, and Utah Senator Mike Lee hold a dim view of more modern architectural styles, such as Brutalism, which proved popular during the 1950s but has largely fallen out of favor, used in most federal buildings from the 1950s onward. However, it singled out the Federal Courthouse in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, completed in 2011, for praise. On the other hand, the American Institute of Architects opposed it. Although they agreed that classical styles are "beautiful," they argued that modern building designs must take into account security, new technology, and efficiency.[110] If signed, the draft order would only apply to federal courthouses, agency headquarters, and other government buildings in the National Capital Region, plus any other federal buildings costing more than $50 million in 2020 values.[111]

- President Trump prefers classical (left) to modern (right) styles of architecture.

Federal Building and Courthouse, Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

Federal Building and Courthouse, Tuscaloosa, Alabama.._Edgar_Hoover_Building_Brunswyk_(2012)_retouched.jpg) FBI J. Edgar Hoover Building, Washington, D.C.

FBI J. Edgar Hoover Building, Washington, D.C.

Telecommunications

Cybersecurity of critical infrastructure

In May 2017, President Trump signed an executive order urging federal agencies to upgrade their antiquated information technology (IT) infrastructure, to draw up plans for coordinated defense, and to comply with cybersecurity standards introduced by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The order also tackles workforce training in order to provide the United States with a "long-term cybersecurity advantage." For his administration, cybersecurity is a priority because a cyber attack on critical infrastructure could inflict "catastrophic regional or national effects on public health or safety, economic security, or national security." Addressing cybersecurity was a 2016 campaign promise from Trump. However, given that three quarters of the federal budget for IT goes to the operating and maintaining legacy systems, additional funding might be necessary.[112]

High-speed Internet

After thinking for a year, President Donald Trump came out against having nationalized fifth-generation wireless internet infrastructure (5G). Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Chairman Ajit Pai said this sent an "important signal" to private companies that were investing billions of dollars in 5G. Pai also proposed spending $20.4 billion over a decade on rural broadband Internet services. Since November 2018, the FCC has been auctioning megahertz of spectrum to commercial wireless internet service providers offering 5G connectivity. FCC Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel said this was a step in the right direction and suggested that the Commission should not leave out "mid-band" spectrum lest the U.S. falls behind other countries.[113] While previous generations of wireless internet offer the ability to send texts, static images, voice, and video through the Internet, 5G is considerably faster, allowing for high-quality video streaming, driverless cars, automated ports, remotely-controlled industrial robots, among other things.[114][115] South Korea and the United States won the global 5G race when they began rolling out their services in early April 2019.[114] Verizon Communications Inc, AT&T Corp, Sprint Corp, and T Mobile US Inc have already begun implementing 5G equipment in a number of American cities with plans to gradually expand service as 5G-compatible phones become more widely available.[113] However, a combination of the high capital costs and high debt levels of leading U.S. telecommunications firm could result in a slow deployment of 5G networks, allowing subsidized Chinese equipment to penetrate markets in Asia and Europe.[116]

President Trump made the above announcement as he was considering banning Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei from the U.S. market. His administration has already been discouraging U.S. allies from purchasing Huawei's 5G technology out of security concerns. His administration believes that Huawei equipment puts intelligence sharing at risk. Since March 2018, the FCC has considered barring the use of federal funds to purchase equipment from companies that could pose a threat to national security.[113] By law, companies operating on Chinese soil must "support, cooperate with and collaborate in national intelligence work."[114]

Founded in 1987, Huawei has since become a leading telecommunications firm, spending 14% of its revenue on research and development each year between 2016 and 2018. However, it has been mired in multiple controversies involving alleged intellectual property theft and espionage.[117] After an 11-month investigation, the U.S. House Intelligence Committee found in 2012 that Huawei and ZTE, another Chinese firm, were threats to national security and recommended that U.S. companies refrain from doing business with them.[117] Under Donald Trump, the U.S. government has been trying to dissuade companies and other governments from around the world from using Huawei's technologies.[117] In May 2019, the Trump administration added Huawei to the "entity list," which prevents it from acquiring technology from American firms without approval from the U.S. government.[118] In October 2019, President Trump met with his Finnish counterpart, Sauli Niinisto, to discuss alternatives to 5G technology from Huawei. Finland's technology giant Nokia has developed some 5G capabilities of its own,[119] and is one of Huawei's chief competitors, alongside Sweden's Ericsson.[120] In December 2017, telecommunications firms from around the world agreed upon a set of global standards for 5G so that the technology can be easily implemented. The race was on for the various equipment manufacturers for global dominance, including Huawei and ZTE from China, Nokia, Ericsson, Qualcomm and Intel (both from the U.S.). 5G is a key part of the geopolitical fault lines created by Donald Trump's desire to "make America great again" and China's stated goal of becoming a global hegemony in artificial intelligence by 2030; this technological race is a part of the U.S.-China trade war.[121]

Telehealth

In late March 2020, President Trump signed into law a stimulus package worth around two trillion dollars, the biggest in American history, in order to alleviate the economic downturn due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Besides cash infusion for front-line hospitals, loans for struggling industries, aid for farmers, enhanced unemployment benefits, relief for married couples with young children, and tax cuts for retailers, it included $200 million for telemedicine. This would help doctors examine their patients remotely, using video-conferencing technology. At present, the FCC operates a rural healthcare program that subsidizes the use of telecommunications technology. FCC Chairman Ajit Pai personally requested this aid in early March.[122] Early that month, the President signed a bipartisan bill that extended Medicare coverage to include telemedicine in outbreak areas. Previously, it was restricted to rural residents who had to take long trips to see a doctor. Telemedicine reduces the need for travel, and therefore chances of vulnerable senior citizens catching COVID-19.[123]

Transportation

Canals, ports, and harbors

The America's Water Infrastructure Act, signed into law by President Trump in October 2018 authorizes $6 billion in spending. Potential recipients for federal funding include the Houston-Galveston Navigation Channel Extension ($15.6 million), and the Ala Wai Canal project in Hawaii ($306.5 million). This bill includes a five-year "Buy American" provision, which requires the use of American-made construction materials used by projects funded by the Act.[124]

Civil aviation

_at_LAX_(22922365062).jpg)

Shortly after taking office in 2017, Donald Trump unveiled an infrastructure plan worth a trillion dollars that includes a $2.4-billion cut to federal transportation programs. This plan would eliminate subsidies for long-distance trains and commercial flights to rural communities with limited transportation options, including those that helped Trump win the presidency. He wanted to relieve the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) of air traffic control and to turn it into a private nonprofit corporation.[125]

In June 2019, the FAA announced it was giving out $840 million in grants for improving airport facilities and President Trump proposed $17.1 billion in funding for the FAA. Trump's proposal made it through the House Appropriations Committee with $614 million more than requested. Therefore, the FAA had $17.7 billion to spend. Airport Improvement Programs (AIP) funds will go to over 380 airports in 47 states. One of the biggest grants is worth $29 million, which goes to runway reconstruction at Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport in Alaska. In addition, the House Appropriations Committee announced $3.3 billion in AIP grants to be handed out in 2020, plus $500 million for discretionary airport infrastructure spending.[126]

Some airliners themselves have been financing airport capital projects on their own. For example, American Airlines and Delta have committed $1.6 billion and $1.8 billion, respectively, to modernize the facilities they use at the Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). Delta allocated another four billion dollars to the construction of a new terminal at the LaGuardia International Airport in New York City. At the same time, a number of airports are willing to spend money on their own facilities in order to reap the long-term economic benefits. In May 2019, the Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport (DFW) announced it would spend some $3.5 billion on a new terminal and on renovating an existing terminal for American Airlines, which uses the airport as one of its main hubs in the U.S.[126]

In early 2020, American airports saw their passenger numbers plummet due to the COVID-19 global pandemic. To help them cope with the crisis, the Trump administration provided $10 billion in financial aid with Congressional approval.[127]

Public transportation

In 2018, the Trump administration rolled out an infrastructure plan that allocates one quarter of the money available to rural areas, even though only 14% of Americans live there. This spells trouble for numerous large-scale urban projects and undermines aging transit networks in large established cities such as Chicago or New York City, which need significant funds for repairs, maintenance, and modernization, because it favors new construction.[note 3] Another key aspect of this policy is that it relegates primary funding responsibility to local authorities and the private sector. Trump's aim with this funding policy is to realize his promise during the 2016 presidential campaign to bring jobs to rural areas, where employment prospects have been dim, and to transfer wealth from states that tend to vote Democrat to those that helped him win the election.[128] According to an analysis of data from the Department of Transportation by McClatchy, the Trump administration has been prioritizing rural transportation projects. Whereas the Obama administration directed 80% of the money from the Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) program to urban projects, under Trump, rural areas got 70% in funding, as of 2019.[129] For example, funding for a proposed Kansas City Streetcar extension was rejected twice by the Trump administration, but money for a highway interchange in nearby Wyandotte County, turned down by the Obama administration, was granted. The Trump administration explained that this shift in priorities is to give rural areas their "fair share" in funding for transportation projects and to re-balance the "historic under-investment in rural America." In fact, while South Carolina received only 15% of what they requested under Obama, under Trump, they received 100%. Moreover, Alaska, Nebraska, Arkansas and Wyoming received more funding in the first two years of Donald Trump than they did under the entire presidency of Barack Obama whereas California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Washington, New York and Illinois, states where Hillary Clinton won, got considerably less money.[129]

.jpg)

The Gateway Program is a plan to modernize railroad infrastructure between New York and New Jersey and to double the number of trains passing between those two states. This plan includes repairs to the old North River Tunnel, and the construction of the new Hudson Tunnel.[130] Existing tunnels between New Jersey and New York are over a century old and were seriously damaged by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. These rail tunnels and the bus terminals are currently operating at full capacity,[131] as are the ferries and roads.[132] They are used by both Amtrak (intercity rail) and NJ Transit (regional rapid transit). If these tunnels were not thoroughly repaired and a new tunnel was not built on time, the number of trains crossing the Hudson River during rush hours could drop from 24 to just six, with dire consequences for the regional economy.[131] In fact, the Northeast Corridor is the most heavily traveled railway in the nation[133] and the region is responsible for 20% of U.S. GDP.[132] Experts estimate that if the Northeast Corridor was closed for just one day, it would cost the U.S. economy $100 million in lost economic activity.[134] The Obama administration tried but failed to fund the project in time. The Obama plan would have 50% of the funding coming from the federal government and the rest from the state governments of New York and New Jersey.[131]

Although he was initially in favor of the Gateway Project, Trump later turned against it and urged fellow Republicans to cut funding for it.[135] Moreover, he dismissed the project as a local one that lacks national importance[132] and a potential boondoggle.[135] He subsequently cut money from the funds for the Gateway Program.[136] While supporters of the Gateway Project argue that it is one of the nation's most pressing infrastructure needs,[132] opponents are wary of additional federal spending and the fact that money will be taken away from smaller projects for their districts.[135] In response to federal inaction, an alternative has been proposed: extending a subway line from New York to New Jersey. Under the plan, the New York City Subway's IRT Flushing Line (7 and <7> trains, currently connecting Flushing, Queens, to Hudson Yards, Manhattan) would go under the Hudson River to an intermodal terminal in Secaucus, New Jersey. It was estimated to cost $6 billion in 2013, half of that of the Gateway program. However, it may not be enough as a replacement for Gateway.[132] In late June 2019, the state governments of New York and New Jersey passed legislation to create the bi-state Gateway Development Commission, whose job it is to oversee the planning, funding and construction of the rail tunnels and bridges of Gateway Program. This bill stipulates that each state is responsible for 50% of the funding and creates standards for transparency and accountability. The Commission is capable of receiving funds from federal, state, and local sources.[137]

Related to the Gateway Program is the Portal Bridge Replacement Project. Going over the Hackensack River in Northern New Jersey, the Portal Bridge is a two-track moveable swing-span rail bridge that is a key piece of infrastructure in the Northeast Corridor. According to Amtrak and NJ Transit, intercity and regional trains carrying a total of 150,000 to 200,000 passengers cross the bridge each weekday. However, because the Portal Bridge is over a century old, it does not always function properly. Delays arise when the bridge fails to close completely.[138] Amtrak and NJ Transit reported that between 2014 and 2018, 85 delays occurred, each lasting for two hours at least.[139] Its proposed replacement would be a fixed structure standing 50 feet (15.24 meters) above mean high water, or twice the current height, thereby eliminating the need for openings. While it would not be able to accommodate additional trains, it would allow trains to cross at 90 mph (144 km/h) instead of just 60 mph (96 km/h).[138] In February 2020, the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) raised the rating of the project from medium-low to medium-high, making it eligible for federal funding and allowing it to enter the engineering phase. It is set to receive $1.7 billion from the federal government. The New Jersey Department of Transportation estimated that once construction begins in full swing, the project would take about five years to complete.[139]

.jpg)

Federal funding for smaller projects, such as $900 million for the Washington Metro's Purple Line, was approved.[140] However, Trump's highly ambitious infrastructure spending plan stalled due to fierce opposition from Democrats who took issue with the fact that Trump preferred private funding and highways to federal funding and public transit. Of the projected $1.5 trillion, the federal government would spend only $200 billion.[141] Under the Obama administration, funding for transit on one hand and for highways and bridges on the other hand were roughly equal. Under the Trump administration, some 70% of the funding would go to highways and bridges and only about 11% to transit.[142]

In February 2019, Governor Gavin Newsom reduced the scale of the California High-speed Rail project, from 520 miles (840 km) linking Los Angeles to San Francisco down to 119 miles (192 km) between Merced and Bakersfield, in response to spiraling costs. The State of California estimated the cost of Phase I of the project to be $77 billion, up $13 billion, but warned that the total cost could reach $100 billion.[143] In fact, the project has been mired in cost overruns and delays. Moreover, even though it was initially planned to have one third of the funding from the private sector, the project failed to raise any funds from that source.[144] In May 2019, the Trump administration cancels $929 million in funding for the construction of the railway, whose trains could travel at speeds of up to 200 miles per hour (320 km/h).[145] In a statement, the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) wrote that the California High-speed Rail Authority (CHSRA) "has failed to make reasonable progress on the Project" and "has abandoned its original vision of a high-speed passenger rail service connecting San Francisco and Los Angeles, which was essential to its applications for FRA grant funding."[146] As of June 2019, the project found itself under investigation for financial malpractice.[145] However, in July 2019, the Trump administration authorized the State of California to assume responsibility for ensuring the project is in compliance with federal environmental protection regulations, thereby lifting a major hurdle.[147]

In June 2019, the FRA announced $326 million in funding for rail infrastructure upgrades for 45 projects in 29 states. These grants come under the Consolidated Rail Infrastructure and Safety Improvement (CRISI) Program, authorized by Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act, and the Special Transportation Circumstances Program. One third of that amount will go to rural areas.[148]

In early April 2020, the Trump administration issued $25 billion in emergency funding for public transportation networks across the United States facing a precipitous drop in ridership due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Approved a week prior by Congress, the money would go primarily to densely populated urban areas, including $5.4 billion for New York City, $1.2 billion for Los Angeles, $1.02 billion for the District of Columbia, $883 million for Boston, $879 million for Philadelphia, $820 million for San Francisco and $520 million for Seattle. Meanwhile, some $2.2 billion would go to rural areas, the FTA announced. National passenger rail company Amtrak received a billion dollars.[127]

Priority transportation infrastructure projects

50 large infrastructure projects with a total worth of $137 billion were prioritized in 2017. In order to qualify, a project must enhance national security, improve public safety, have 30% of its design complete, and be ready for construction.[106] The following list taken from the top ten civil engineering projects that pertain to transportation. They are all public-private partnerships.[106]

- Second Avenue Subway, New York City, $14.2 billion. Phase 1 was completed on January 1, 2017.[149] Phase II is underway.[150] There are four phases total. When completed, the Second Avenue Subway would be 8.6 miles (13.8 km) long with 16 stations and an estimated daily ridership of 560,000.[106] First proposed in 1919, this is the first major New York City Subway expansion in over half a century. The stations feature climate controls, wheelchair accessibility, wireless Internet, escalators, and elevators.[151]

.jpg) Phase I of the New York Second Avenue Subway entered service in early 2017.

Phase I of the New York Second Avenue Subway entered service in early 2017. - Gateway Program, New York and New Jersey, $12 billion.[106] This project is described in detail above.

- Texas Central Railway, $12 billion. This is the 241-mile (388 km) private high-speed rail line that connects Houston to Dallas and cuts travel time from four and a half hours to just 90 minutes. At present, some 50,000 people travel along that route each week on the road.[106][152] Its rolling stock will consist of the export version of the N-700 Series bullet train from Japan.[152]

- Washington Union Station Expansion and Refurbishment, District of Columbia, $8.7 billion. This is the second busiest train station in the United States and one of its national treasures. The project aims to renovate the concourse, temporarily closed in 1981 due to the risk of structural collapse, and the surrounding railways.[106] Scheduled to begin in Fall 2019, work will double the passenger capacity of Amtrak's concourse and will improve access between it and the Washington Metro's station.[153] Amtrak said revitalizing the concourse will take about three years because the work "must be phased in order to avoid an unacceptable level of degradation to passenger capacity and retail disruption, while maintaining passenger access to train gates, Metrorail, and bus deck during construction."[154] This intermodal transportation hub serves 100,000 passengers daily and is the busiest entryway to the Metro, with 28,000 riders each day, many of whom transfer from intercity rail, commuter rail, or buses.[153]

- 15 bridges on Interstate 95 in Pennsylvania, $8 billion. All of them need to be rebuilt or replaced urgently. Tolling might be introduced, though this suggestion has proved to be controversial.[106]

- Purple Line, Maryland, $5.6 billion. This railway adds 16 miles (26 km) to the Washington Metro. This project was scheduled to go ahead regardless of election results.[106] Construction began in August 2017 and the Line is expected to open in October 2022.[155] The Purple Line enables passengers to access the Red, Green, and Orange Lines of the Washington Metro without having to travel through central Washington, D.C. (See diagram on the right.)

Diagram of the Washington Metro.

Diagram of the Washington Metro. - Gordie Howe International Bridge, $4.5 billion, between Detroit, Michigan and Windsor, Ontario. This cable-stayed bridge will connect the U.S. state of Michigan to the Canadian province of Ontario, allowing for more traffic to flow between the two neighbors and reducing dependence on the Ambassador Bridge, which currently carries 2.5 million cargo trucks per year, or 30% of truck traffic between Canada and the U.S.[106] The Bridging North America consortium, created to build and maintain the bridge, estimated that the project will create 2,500 jobs. There will be a multi-purpose path for pedestrians and cyclists and three lanes for vehicles in each direction. Construction commenced in October 2018 and is scheduled to complete in late 2024.[156] Once completed, it will be 853 m (0.53 mi) across and 2.5 km (1.56 mi) long, making it the longest cable-stayed bridge in North America.[157]

Water management

In October 2018, President Trump signed into law the America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018, allocating more than $6 billion on water infrastructure spending of all kinds.[158] This bipartisan bill authorizes the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to manage water resource projects and policies nationwide. It also authorizes federal funding for various water infrastructure projects, including the expansion of water storage capabilities, and upgrades to wastewater, drinking and irrigation systems.[159] This bill includes some $2.2 billion for a coastal barrier Texas, protecting it from flood in the future. The coastal barrier includes not just flood walls and sea walls but also pumping stations, drainage facilities, and floodgates for highways and railroads. The money may also be used for ecosystem repair, upgrades to port and inland waterways, flood control, dam renovations, and enhancing drinking water facilities. Moreover, the Act reauthorizes the Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act loan program.[160]

In April 2019, after signing two executive orders on energy infrastructure projects, President Trump said he would order the Environmental Protection Agency to issue guidelines for state compliance with the Clean Water Act.[9]

In May 2019, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) made $2.6 billion available for water infrastructure improvement across the United States. According to the Agency's own estimates, some $743 billion is needed, and the State Resolving Funds (SRFs), which require states to match federal funding and repay loans and interests, have provided $170 billion.[161]

See also

- East Side Access, a rail extension project in New York City.

- Hudson Yards Redevelopment Project, a private real-estate project in New York City.

- Silver Line (Washington Metro)

- Rebuild Illinois, an infrastructure spending bill.

- Pork barrel, a term with negative connotations for public spending

- Infrastructure-based development

- Infrastructure and economics

Further reading

- Ascher, Kate (2005). The Works: Anatomy of a City. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1594200717.

- Ferguson, Charles (2011). Nuclear Energy: What Everyone Needs to Know. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19975-946-0.

- Prud'homme, Alex (2014). Hydrofracking: What Everyone Needs to Know. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-931126-2.

- Spieler, Christof (2018). Trains, Buses, People - An Opinionated Atlas of US Transit. Canada: Island Press. ISBN 978-1-61091-903-6.

Notes

- This number translates to 7.3% of Americans, assuming a population of 330 million.

- See Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction.

- This does not mean such cities have no need or plans for transit expansions. See, for example, the Chicago "L" Red Line Extension.

References

- "Trump aides try to quash tax hike rumors amid infrastructure talks". Politico. May 17, 2019. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- Edwards, Hayley Sweetlands (March 4, 2016). "Trump Agrees With Democrats on High-Speed Trains". Time. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- Broderick, Timmy (May 22, 2019). "Both parties agree infrastructure needs fixing. So why hasn't it happened?". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- Laing, Keith (September 30, 2015). "Trump takes a shot at NYC's LaGuardia Airport". The Hill. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- Eatwell, Roger; Goodwin, Matthew (2018). "Chapter 2: Promises". National Populism - The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy. Great Britain: Pelican Book. ISBN 978-0-241-31200-1.

- Eatwell, Roger; Goodwin, Matthew (2018). "Chapter 10: Towards Post-populism". National Populism - The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy. Great Britain: Pelican Book. ISBN 978-0-241-31200-1.

- Donald J. Trump. Executive Order on Strengthening Buy-American Preferences for Infrastructure Projects. Issued January 31, 2019.

- Trump orders agencies to buy U.S.-made steel, aluminum and cement 'to the greatest extent' possible. Financial Post. February 7, 2019. Accessed February 11, 2019.