San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge

The San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, known locally as the Bay Bridge, is a complex of bridges spanning San Francisco Bay in California. As part of Interstate 80 and the direct road between San Francisco and Oakland, it carries about 260,000 vehicles a day on its two decks.[3][4] It has one of the longest spans in the United States.

San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge | |

|---|---|

The western section of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge | |

| Coordinates | 37°49′5″N 122°20′48″W |

| Carries | 10 lanes of |

| Crosses | San Francisco Bay via YBI |

| Locale | San Francisco and Oakland, California, United States |

| Owner | State of California |

| Maintained by | California Department of Transportation and the Bay Area Toll Authority |

| ID number |

|

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Double-decked suspension spans (two, connected by center anchorage), tunnel, cast-in-place concrete transition span, self-anchored suspension span, precast segmental concrete viaduct |

| Material | Steel, concrete |

| Total length | West: 10,304 ft (3,141 m) East span: 10,176 ft (3,102 m) Total: 4.46 miles (7.18 km) excluding approaches |

| Width | West: 5 traffic lanes totaling 57.5 ft (17.5 m) East: 10 traffic lanes totaling 258.33 ft (78.74 m) |

| Height | West: 526 ft (160 m)[2] |

| Longest span | West: two main spans 2,310 ft (704 m) East: one main span 1,400 ft (430 m) |

| Clearance above | Westbound: 14 feet (4.3 m), with additional clearance in some lanes Eastbound: 14.67 feet (4.47 m) |

| Clearance below | West: 220 feet (67 m) East: 190 feet (58 m) |

| History | |

| Designer | Charles H. Purcell |

| Construction start | July 8, 1933 |

| Opened | November 12, 1936 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 260,000[3][4] |

| Toll | Cars (east span, westbound only) $7.00 (rush hours) $2.50 (carpool rush hours) $5.00 (weekday non-rush hours) $6.00 (weekend all day) |

| Designated | August 13, 2001 |

| Reference no. | 00000525[1][5] |

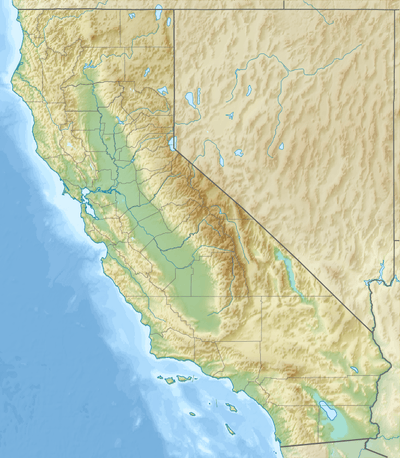

San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge Location in California | |

The toll bridge was conceived as early as the California Gold Rush days, but construction did not begin until 1933. Designed by Charles H. Purcell,[6][7] and built by American Bridge Company, it opened on Thursday, November 12, 1936, six months before the Golden Gate Bridge. It originally carried automobile traffic on its upper deck, with trucks, cars, buses and commuter trains on the lower, but after the Key System abandoned rail service, the lower deck was converted to all-road traffic as well. In 1986, the bridge was unofficially dedicated to James Rolph.[8]

The bridge has two sections of roughly equal length; the older western section, officially known as the Willie L. Brown Jr. Bridge (after former San Francisco Mayor and California State Assembly Speaker Willie L. Brown Jr.), connects downtown San Francisco to Yerba Buena Island, and the newer unnamed eastern section connects the island to Oakland. The western section is a double suspension bridge with two decks, westbound traffic being carried on the upper deck while eastbound is carried on the lower one. The largest span of the original eastern section was a cantilever bridge. During the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, a portion of the eastern section's upper deck collapsed onto the lower deck and the bridge was closed for a month. Reconstruction of the eastern section of the bridge as a causeway connected to a self-anchored suspension bridge began in 2002; the new eastern section opened September 2, 2013, at a reported cost of over $6.5 billion, a 2,500% cost overrun from the original estimate of $250 million (for a seismic retrofit of the existing span).[9][10] Unlike the western section and the original eastern section of the bridge, the new eastern section is a single deck with the eastbound and westbound lanes on each side making it the world's widest bridge, according to Guinness World Records,[11] as of 2014. Demolition of the old east span was completed on September 8, 2018.[12]

Background

The bridge consists of two crossings, east and west of Yerba Buena Island, a natural mid-bay outcropping inside San Francisco city limits. The western crossing between Yerba Buena and downtown San Francisco has two complete suspension spans connected at a center anchorage.[13] Rincon Hill is the western anchorage and touch-down for the San Francisco landing of the bridge connected by three shorter truss spans. The eastern crossing, between Yerba Buena Island and Oakland, was a cantilever bridge with a double-tower span, five medium truss spans, and a 14-section truss causeway. Due to earthquake concerns, the eastern crossing was replaced by a new crossing that opened on Labor Day 2013.[14] On Yerba Buena Island, the double-decked crossing is a 321-foot (98 m) concrete viaduct east of the west span's cable anchorage, the 540-foot (160 m) Yerba Buena Tunnel through the island's rocky central hill, another 790.8-foot (241.0 m) concrete viaduct, and a longer curved high-level steel truss viaduct that spans the final 1,169.7 feet (356.5 m) to the cantilever bridge.[15]

The toll plaza on the Oakland side (since 1969 for westbound traffic only) has eighteen toll lanes, of which six are FasTrak-only. Metering signals are about 1,000 feet (300 m) west of the toll plaza. Two full-time bus-only lanes bypass the toll booths and metering lights around the right (north) side of the toll plaza; other high occupancy vehicles can use these lanes during weekday morning and afternoon commute periods. The two far-left toll lanes are high-occupancy vehicle lanes during weekday commute periods. Radio and television traffic reports will often refer to congestion at the toll plaza, metering lights, or a parking lot in the median of the road for bridge employees; the parking lot is about 1,900 feet (580 m) long, stretching from about 800 feet (240 m) east of the toll plaza to about 100 feet (30 m) west of the metering lights.[16]

During the morning commute hours, traffic congestion on the westbound approach from Oakland stretches back through the MacArthur Maze interchange at the east end of the bridge onto the three feeder highways, Interstate 580, Interstate 880, and I-80 toward Richmond.[17] Since the number of lanes on the eastbound approach from San Francisco is structurally restricted, eastbound backups are also frequent during evening commute hours.

The western section of the Bay Bridge is currently restricted to motorized freeway traffic. Pedestrians, bicycles, and other non-freeway vehicles are not allowed to cross this section. A project to add bicycle/pedestrian lanes to the western section has been proposed but is not finalized. A Caltrans bicycle shuttle operates between Oakland and San Francisco during peak commute hours for $1.00 each way.[18]

Freeway ramps next to the tunnel provide access to Yerba Buena Island and Treasure Island. Because the toll plaza is on the Oakland side, the western span is a de facto non-tolled bridge; traffic between the island and the main part of San Francisco can freely cross back and forth. Those who only travel from Oakland to Yerba Buena Island, and not the entire length to the main part of San Francisco, must pay the full toll.

History

San Francisco, at the entrance to the bay, was perfectly placed to prosper during the California Gold Rush. Almost all goods not produced locally arrived by ship. But after the first transcontinental railroad was completed in May 1869, San Francisco was on the wrong side of the Bay, separated from the new rail link. The fear of many San Franciscans was that the city would lose its position as the regional center of trade. The concept of a bridge spanning the San Francisco Bay had been considered since the Gold Rush days. Several newspaper articles during the early 1870s discussed the idea. In early 1872, a "Bay Bridge Committee" was hard at work on plans to construct a railroad bridge. The April 1872 issue of the San Francisco Real Estate Circular contained an item about the committee:

The Bay Bridge Committee lately submitted its report to the Board of Supervisors, in which compromise with the Central Pacific was recommended; also the bridging of the bay at Ravenswood and the granting of railroad facilities at Mission Bay and on the water front. Wm. C. Ralston, ex-Mayor Selby and James Otis were on this committee. A daily newspaper attempts to account for the advice of these gentlemen to the city by hinting that they were afraid of the railroad company, and therefore made their recommendations to suit its interests.[19]

The self-proclaimed Emperor Norton saw fit to decree three times in 1872 that a suspension bridge be constructed to connect Oakland with San Francisco. In the third of these decrees, in September 1872, Norton, frustrated that nothing had happened, proclaimed:

WHEREAS, we issued our decree ordering the citizens of San Francisco and Oakland to appropriate funds for the survey of a suspension bridge from Oakland Point via Goat Island; also for a tunnel; and to ascertain which is the best project; and whereas the said citizens have hitherto neglected to notice our said decree; and whereas we are determined our authority shall be fully respected; now, therefore, we do hereby command the arrest by the army of both the Boards of City Fathers if they persist in neglecting our decrees. Given under our royal hand and seal at San Francisco, this 17th day of September, 1872.[20]

Unlike most of Emperor Norton's eccentric ideas, his decree to build a bridge had wide public and political appeal. Yet the task was too much of an engineering and economic challenge, since the bay was too wide and too deep there. In 1921, over forty years after Norton's death, a tube was considered, but it became clear that one would be inadequate for vehicular traffic.[22] Support for a trans-bay crossing finally grew in the 1920s with the increasing popularity and availability of the automobile.

Planning

A law became effective in 1929 to establish the California Toll Bridge Authority (Stats. 1929, Chap 763) and to authorize it and the State Department of Public Works to build a bridge connecting San Francisco and Alameda County (Stats. 1929, Chap 762).[23][24]

A commission was appointed to evaluate the idea and various designs for a bridge across the Bay, the Hoover-Young Commission. Its conclusions were made public in 1930.[25]

In January 1931, Charles H. Purcell, the State Highway Engineer of California, assumed the position of Chief Engineer for the Bay Bridge.

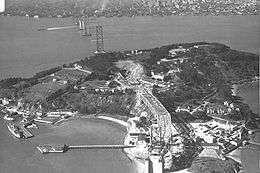

To make the bridge feasible, a route was chosen via Yerba Buena Island, which would reduce both the material and the labor needed. Since Yerba Buena Island was a U.S. Navy base at the time, the approval of the U.S. Congress, which regulates the armed services and supervises all naval and military bases, was necessary for this island to be used. After a great deal of lobbying, California received Congressional approval to use the island on February 20, 1931, subject to the final approval of the Departments of War, Navy and Commerce.[26] Permits were immediately applied for from the 3 federal departments as required. The permits were granted in January, 1932, and formally presented in a ceremony on Yerba Buena Island on February 24, 1932.[27]

On May 25, 1931, Governor James Rolph Jr. signed into law two acts: one providing for the financing of state bridges by revenue bonds, and another creating the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge Division of the State Department of Public Works. On September 15, 1931, this new division opened its offices at 500 Sansome Street in San Francisco.[28]

During 1931, a series of aerial photographs was taken of the chosen route for the bridge and its approaches.[29]

The final design concept for the western span between San Francisco and Yerba Buena Island was still undecided in 1931, although the idea of a double-span suspension bridge was already favored.[30]

In April 1932, the preliminary final plan and design of the bridge was presented by Chief Engineer Charles Purcell to Col. Walter E. Garrison, Director of the State Department of Public Works, and to Ralph Modjeski, head of the Board of Engineering Consultants. Both agencies approved and preparation of the final design proceeded.[31][32]

Construction

Before work got underway, 12 massive underwater telephone cables were moved 1,000 feet north of the proposed bridge route by crews of the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Co. during the summer of 1931.[33]

Construction began on July 9, 1933.[34] Ultimately, twenty-four men would die constructing the bridge.[35]

The western section of the bridge between San Francisco and Yerba Buena Island presented an enormous engineering challenge. The bay was up to 100 feet (30 m) deep in places and the soil required new foundation-laying techniques.[22] A single main suspension span some 4,100 feet (1.2 km) in length was considered but rejected, as it would have required too much fill and reduced wharfage space at San Francisco, had less vertical clearance for shipping, and cost more than the design ultimately adopted.[36] The solution was to construct a massive concrete anchorage halfway between San Francisco and the island, and to build a main suspension span on each side of this central anchorage.[37]

East of Yerba Buena Island, the bay to Oakland was spanned by a 10,176-foot (3.102 km) combination of double cantilever, five long-span through-trusses, and a truss causeway, forming the longest bridge of its kind at the time.[22] The cantilever section was longest in the nation and third-longest anywhere.[38]

Much of the original eastern section was founded upon treated wood pilings. Because of the very deep mud on the bay bottom it was not practical to reach bedrock, although the lower levels of the mud are quite firm. Long wooden pilings were crafted from entire old-growth Douglas fir trees, which were driven through the soft mud to the firmer bottom layers.[39]

Approaches

The original western approach to (and exit from) the upper deck of the bridge was a long ramp to Fifth, branching to Harrison St for westward traffic off the bridge and Bryant St for eastward traffic entering. There was an on-ramp to the upper deck on Rincon Hill from Fremont Street (which later became an off-ramp) and an off-ramp to First Street (later extended over First St to Fremont St). The lower deck ended at Essex and Harrison St; just southwest of there, the tracks of the bridge railway left the lower deck and curved northward into the elevated loop through the Transbay Terminal that was paved for buses after rail service ended.[40]

The eastern approach to the bridge included a causeway landing for the "incline" section, and the construction of three feeder highways, interlinked by an extensive interchange,[41] which in later years became known as "The MacArthur Maze". A massive landfill was emplaced, extending along the north edge of the existing Key System rail mole to the existing bayshore, and continuing northward along the shore to the foot of Ashby Avenue in Berkeley.[42] The fill was continued northward to the foot of University Avenue as a causeway which enclosed an artificial lagoon, subsequently developed by the WPA as "Aquatic Park". The 3 feeder highways were U.S. 40 (Eastshore Highway) which led north through Berkeley, U.S. 50 (38th Street, later MacArthur Blvd.) which led through Oakland, and State Route 17 which ran parallel to U.S. 50, along the Oakland Estuary and through the industrial and port sections of the city.

Yerba Buena Tunnel

The Yerba Buena passage utilizes the Yerba Buena Tunnel, 76 feet (23 m) wide, 58 feet (18 m) high, and 540 feet (160 m) long.[15] It is the largest diameter transportation bore tunnel in the world.[22] The large amount of material that was excavated in boring the tunnel was used for a portion of the landfill over the shoals lying adjacent to Yerba Buena Island to its north, a project which created the artificial Treasure Island.

Reminders of the long-gone bridge railway survive along the south side of the lower Yerba Buena Tunnel. These are the regularly spaced refuge bays ("deadman holes"), escape alcoves common in all railway tunnels, along the wall, into which track maintenance workers could safely retreat if a train came along. (The north side, which always carried only motor traffic, lacks these holes.)[43][44]

Opening day

The bridge opened on November 12, 1936, at 12:30 p.m. In attendance were the former US president Herbert Hoover, Senator William G. McAdoo, and the Governor of California, Frank Merriam. Governor Merriam opened the bridge by cutting gold chains across it with an acetylene cutting torch.[45] The San Francisco Chronicle report of November 13, 1936, read:

.png)

the greatest traffic jam in the history of S.F., a dozen old-fashioned New Year's eves thrown into one – the biggest and most good-natured crowd of tens of thousands ever to try and walk the streets and guide their autos on them – This was the city last night, the night of the bridge opening with every auto owner in the bay region, seemingly, trying to crowd his machine onto the great bridge.

And those who tried to view the brilliantly lighted structure from the hilltops and also view the fireworks display were numbered also in the thousands.

Every intersection in the city, particularly those near the San Francisco entrance to the bridge, was jammed with a slowly moving auto caravan.

Every available policeman in the department was called to duty to aid in regulating the city's greatest parade of autos.

One of the greatest traffic congestions of the evening was at Fifth and Mission Streets, with downtown traffic and bridge-bound traffic snarled in an almost hopeless mass. To add to the confusion, traffic signals jammed and did not synchronize.

Police reported that there was no lessening of the traffic over the bridge, all lanes being crowded with Oakland- or San-Francisco-bound machines far into the night.

The total cost was US$77 million.[22] Before opening the bridge was blessed by Cardinal Secretary of State Eugene Cardinal Pacelli, later Pope Pius XII.[46] Because it was in effect two bridges strung together, the western spans were ranked the second and third largest suspension bridges. Only the George Washington Bridge had a longer span between towers.

As part of the celebration a United States commemorative coin was produced by the San Francisco Mint. A half dollar, the obverse portrays California's symbol, the grizzly bear, while the reverse presents a picture of the bridge spanning the bay. A total of 71,369 coins were sold, some from the bridge's tollbooths.[47]

Roadway plan

Until the 1960s the upper deck (58 feet (18 m) wide between curbs) carried three lanes of traffic in each direction and was restricted to automobiles only.[22] The lower deck carried three lanes of truck and bus traffic, with autos allowed, on the north side of the bridge.[22] In the 1950s traffic lights were added to set the direction of travel in the middle lane, but there still remained no divider. Two interurban railroad tracks on the south half of the lower deck carried the electric commuter trains.[48] In 1958 the tracks were replaced with pavement, but the reconfiguration to what the traffic eventually became did not take place until 1963.

The Federal highway on the bridge was originally a concurrency of U.S. Highway 40 and U.S. Highway 50. The bridge was re-designated as Interstate 80 in 1964, and the western ends of U.S. 40 and U.S. 50 are now in Silver Summit, Utah, and West Sacramento, California, respectively.

The off-ramp for Treasure Island and Yerba Buena Island is unusual in that it is on the left-hand side in the eastbound direction. This off ramp presents an unusual hazard – drivers must slow within the normal traffic flow and move into a very short off-ramp that ends in a short radius turn left turn; accordingly, a 15 MPH advisory is posted there. The turn has been further narrowed from its original design by the installation of crash pads on the island side. Eastbound and westbound on-ramps are on the usual right-hand side, but these do not have dedicated merge lanes, forcing drivers to await gaps in traffic and then accelerate from a stop sign to traffic speeds in a short distance. In 2016, a new on-ramp and off-ramp to Treasure Island were opened in the western direction on the right-hand side of the roadway, replacing the left-hand side off-ramp in that direction.[49]

Rail service

On January 14, 1939, the San Francisco Transbay Terminal was dedicated. The following morning, January 15, 1939, the electric commuter trains started running across the south side of the lower deck of the bridge. The terminal originally was supposed to open the same time as the Bay Bridge, but was delayed. The trains were operated by the Sacramento Northern Railroad (Western Pacific), the Interurban Electric Railway (Southern Pacific) and the Key System.[50] Freight trains never used the bridge. The tracks left the lower deck in San Francisco just southwest of the end of 1st St. They then went along an elevated viaduct above city streets, looping around and into the terminal on its east end. Departing trains exited on the loop back onto the bridge.[51] The loop continued to be used by buses until the terminal's closure in 2010. The tracks left the lower deck in Oakland. The Interurban Electric Railway tracks ran along Engineer Road and over the Southern Pacific yard on trestles (some of it is still standing and visible from nearby roadways) onto the streets and dedicated right-of-ways in Berkeley, Albany, Oakland and Alameda. The Sacramento Northern and Key System tracks went under the SP tracks through a tunnel (which still exists and is in use as an access to the EBMUD treatment plant) and onto 40th St. Due to falling ridership, Sacramento Northern and IER service ended in 1941.[52] After World War II Key System ridership began to fall as well.[53] Despite the vital role the railroad played, the last train went over the bridge in April 1958. The tracks were removed and replaced with pavement on the Transbay Terminal ramps and Bay Bridge. The Key System handled buses over the bridge until 1960 when its successor, AC Transit, took over operations. It still handles service today. There have been several attempts to restore rail service on the bridge, but none have been successful.

Later events

Modification to remove rail service

Automobile traffic increased dramatically in the ensuing decades while the Key System declined, and in October 1963, the Bay Bridge was reconfigured with five lanes of westbound traffic on the upper deck and five lanes of eastbound traffic on the lower deck. The Key System originally planned to end train operations in 1948 when it replaced its streetcars with buses, but Caltrans did not approve of this. Trucks were allowed on both decks and the railroad was removed.[22] Owing to a lack of clearance for trucks through the upper-deck portion of the Yerba Buena tunnel, it was necessary to lower the elevation of the upper deck where it passes through the tunnel, and to correspondingly excavate to lower the elevation of the lower portion.[54] Additionally, the upper deck was retrofitted to handle the increased loads due to trucks, with understringers added and prestressing added to the bottom of the floor beams. This retrofit is still in place and is visible to Eastbound traffic.

1968 aircraft accident

On February 11, 1968, a U.S. Navy training aircraft crashed into the cantilever span of the bridge, killing both reserve officers aboard. The T2V SeaStar, based at NAS Los Alamitos in southern California, was on a routine weekend mission and had just taken off in the fog from nearby NAS Alameda. The plane struck the bridge about 15 feet (5 m) above the upper deck roadway and then sank in the bay north of the bridge.[55] There were no injuries among the motorists on the bridge.[56] One of the truss sections of the bridges was replaced due to damage from the impact.[57]

Cable lighting

The series of lights adorning the suspension cables was added in 1986 as part of the bridge's 50th-anniversary celebration.[58]

Ship accident

In 2007, a container ship then named the Cosco Busan, and subsequently renamed the Hanjin Venezia, struck the bridge, resulting in the Cosco Busan oil spill.

2013 public "light sculpture" installation

On March 5, 2013, a public art installation called "The Bay Lights" was activated on the western span's vertical cables. The installation was designed by artist Leo Villareal and consists of 25,000 LED lights originally scheduled to be on nightly display until March 2015.[59] However, on December 17, 2014, the non-profit Illuminate The Arts announced that it had raised the $4 million needed to make the lights permanent; the display was temporarily turned off starting in March 2015 in order to perform maintenance and install sturdier bulbs and then re-lit on January 30, 2016.[60][61]

In order to reduce driver distractions, the privately funded display is not visible to users of the bridge, only to distant observers. This lighting effort is intended to form part of a larger project to "light the bay".[62] Villareal used various algorithms to generate patterns such as rainfall, reflections on water, bird flight, expanding rings, and others. Villareal's patterns and transitions will be sequenced and their duration determined by computerized random number generator to make each viewing experience unique.[63] Owing to the efficiency of the LED system employed, the estimated operating cost is only US$15.00 per night.

Bus lane proposal

In January 2020, the AC Transit and BART boards of directors supported the establishment of dedicated bus lanes on the bridge.[64] In February 2020, Rob Bonta introduced state legislation to begin planning bus lanes.[65]

Earthquake damage and subsequent upgrades

On the evening of October 17, 1989 during the Loma Prieta earthquake, which measured 6.9 on the moment magnitude scale,[66] a 50-foot (15 m) section of the upper deck of the eastern truss portion of the bridge at Pier E9 collapsed onto the deck below, indirectly causing one death. The bridge was closed for just over a month as construction crews repaired the section. That same year, the bridge reopened to traffic on November 18. The lighter pavement of the replacement section is visible in aerial photographs at the east end of the through-truss part of the bridge (37.8189°N 122.3442°W).

Western section retrofitting

The western section has undergone extensive seismic retrofitting. During the retrofit, much of the structural steel supporting the bridge deck was replaced while the bridge remained open to traffic. Engineers accomplished this by using methods similar to those employed on the Chicago Skyway reconstruction project.[67]

The entire bridge was fabricated using hot steel rivets, which are impossible to heat treat and so remain relatively soft. Analysis showed that these could fail by shearing under extreme stress. Therefore, at most locations each given rivet was removed by breaking off the head with a jack-hammer [rivet buster] and punching out the old rivet, the hole precision reamed and the old rivets replaced with heat-treated high-strength tension-control [TC] bolts and nuts. Most bolts had domed heads placed facing traffic so they looked similar to the rivets that were removed.[Caltrans contract 04-0435U4, 1999–2004]. This work had to be performed with great care as the steel of the structure had for many years been painted with lead based paint, which had to be carefully removed and contained by workers with extensive protective gear.

.jpg)

Most of the beams were originally constructed of two plate I-beams joined with lattices of flat strip or angle stock, depending upon structural requirements. These have all been reconstructed by replacing the riveted lattice elements with bolted steel plate and so converting the lattice beams into box beams. This replacement included adding face plates to the large diagonal beams joining the faces of the main towers, which now have an improved appearance when viewed from certain angles.

Diagonal box beams have been added to each bay of the upper and lower decks of the western spans. These add stiffness to reduce side-to-side motion during an earthquake and reduce the probability of damage to the decking surfaces.

Analysis showed that some massive concrete supports could burst and crumble under likely stresses. In particular the western supports were extensively modified. First, the location of existing reinforcing bar is determined using magnetic techniques. In areas between bars holes are drilled. Into these holes is inserted and glued an L-shaped bar that protrudes 15 to 25 centimeters (6 to 10 inches). This bar is retained in the hole with a high-strength epoxy adhesive. The entire surface of the structure is thus covered with closely spaced protrusions. A network of horizontal and vertical reinforcing bars is then attached to these protrusions. Mold surface plates are then positioned to retain high-strength concrete, which is then pumped into the void. After removal of the formwork the surface appears similar to the original concrete. This technique has been applied elsewhere throughout California to improve freeway overpass abutments and some overpass central supports that have unconventional shapes. (Other techniques such as jacket and grout are applied to simple vertical posts; see the seismic retrofit article.)

The western approaches have also been retrofitted in part, but mostly these have been replaced with new construction of reinforced concrete.

Eastern section replacement

For various reasons, the eastern section would have been too expensive to retrofit compared to replacing it, so the decision was made to replace it.

The replacement section underwent a series of design changes, both progressive and regressive, with increasing cost estimates and contractor bids. The final plan included a single-towered self-anchored suspension span starting at Yerba Buena island, leading to a long inclined viaduct to the Oakland touchdown.

Separated and protected bicycle lanes are a visually prominent feature on the south side of the new eastern section. The bikeway and pedestrian path across the eastern span opened in October 2016 and carries recreational and commuter cyclists between Oakland and Yerba Buena Island.[68] The original eastern cantilever span had firefighting dry standpipes installed. No firefighting dry or wet standpipes were designed for the eastern section replacement, although, the firefighting wet standpipes do exist on the original western section visible on both the north-side upper and lower decks.

The original eastern section closed permanently to traffic on August 28, 2013, and the replacement span opened for traffic five days later.[69] The old original eastern section was dismantled between January 2014 and November 2017.[70][71]

- Eastern span: original and replacement

Some new construction (2004)

Some new construction (2004) Substantial progress (2011)

Substantial progress (2011)- The completed replacement and the old bridge (2013)

- Rest of old and new bridge (June 2015)

Artist's simulation of final appearance after old span demolition

Artist's simulation of final appearance after old span demolition

October 2009 eyebar crack, repair failure and bridge closure

During the 2009 Labor Day weekend closure for a portion of the replacement, a major crack was found in an eyebar, significant enough to warrant bridge closure.[72] Working in parallel with the retrofit, California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), and its contractors and subcontractors, were able to design, engineer, fabricate, and install the pieces required to repair the bridge, delaying its planned opening by only 1 1⁄2 hours. The repair was not inspected by the Federal Highway Administration, which relied on state inspection reports to ensure safety guidelines were met.[73]

On October 27, 2009 during the evening commute, the steel crossbeam and two steel tie rods repaired over Labor Day weekend[74] snapped off the Bay Bridge's eastern section and fell to the upper deck.[75][76][77] This may have been due to metal-on-metal vibration from bridge traffic and wind gusts of up to 55 miles per hour (90 km/h), which resulted in one of the rods breaking off and caused one of the metal sections to come crashing down.[78] Three vehicles were either struck by or hit the fallen debris, though there were no injuries.[79][80][81][82] On November 1, Caltrans announced that the bridge would probably stay closed at least through the morning commute of Monday, November 2 after repairs performed during the weekend failed a stress test on Sunday.[83] BART and the Golden Gate Ferry systems added supplemental service to accommodate the increased passenger load during the bridge closure.[84] The bridge reopened to traffic on November 2, 2009.

The pieces that broke off on October 27 were a saddle, crossbars, and two tension rods.[79][85]

Name

The bridge was unofficially "dedicated" to James B. "Sunny Jim" Rolph, Jr.,[86] but this was not widely recognized until the bridge's 50th-anniversary celebrations in 1986. The official name of the bridge for all functional purposes has always been the "San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge", and, by most local people, it is referred to simply as "the Bay Bridge".

Rolph, a Mayor of San Francisco from 1912 to 1931, was the Governor of California at the time construction of the bridge began. He died in office on June 2, 1934, two years before the bridge opened, leaving the bridge to be named for him out of respect.[22] In 1932, with an inability to finance the bridge, Joseph R. Knowland, (a former U.S. Congressman) travelled to Washington and helped to persuade President Herbert Hoover and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to advance $62 million for the building of the bridge.

Emperor Norton naming campaign

In 1872, the San Francisco entrepreneur and eccentric Emperor Norton issued three proclamations calling for the design and construction of a suspension bridge between San Francisco and Oakland via Yerba Buena Island (formerly Goat Island).[87]

A 1939 plaque honoring Emperor Norton for the original idea for the Bay Bridge was dedicated by the fraternal society E Clampus Vitus and was installed at The Cliff House in February 1955. In November 1986, in connection with the bridge's 50th anniversary, the plaque was moved to the Transbay Terminal, the public transit and Greyhound bus depot at the west end of the bridge in downtown San Francisco. When the terminal was closed in 2010, the plaque was placed in storage.[88]

There have been two recent campaigns to name all, or parts, of the Bay Bridge for Emperor Norton.[89]

2004

In November 2004, after a campaign by San Francisco Chronicle cartoonist Phil Frank, then-San Francisco District 3 Supervisor Aaron Peskin introduced a resolution to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors calling for the entire two-bridge system, from San Francisco to Oakland, to be named for Emperor Norton.[90]

On December 14, 2004, the Board approved a modified version of this resolution, calling for only "new additions" — i.e., the new eastern crossing — to be named "The Emperor Norton Bridge".[20] Neither the City of Oakland nor Alameda County passed any similar resolution, so the effort went no further.

2013

In June 2013, nine state assemblymen, joined by two state senators, introduced Assembly Concurrent Resolution No. 65 (ACR 65) to name the western crossing of the bridge for former California Assembly Speaker and former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown.[91] Six weeks later, a grassroots petition was launched seeking to rename the entire two-bridge system for Emperor Norton.[92] In September 2013, the petition's author launched a nonprofit, The Emperor's Bridge Campaign, that advocates for adding a name to honor Emperor Norton (rather than "renaming" the bridge) and that undertakes other efforts to advance Norton's legacy.

2014

The state legislative resolution naming the western section of the Bay Bridge the "Willie L. Brown, Jr., Bridge" passed the Assembly in August 2013 and the Senate in September 2013.[93] A ceremony was held on February 11, 2014, marking the resolution and the installation of signs on either end of the section.[94]

The larger entity of which the western section is a part retains the separate and independent designation "San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge".[86]

Alexander Zuckermann Bike Path

The pedestrian and bicycle route on the eastern section opened on September 3, 2013, and is named after Alexander Zuckermann, founding chair of the East Bay Bicycle Coalition.[95] This forms a transbay route for the San Francisco Bay Trail. Until October 2016, the path did not connect to Yerba Buena and Treasure Island sidewalks, due to the need to demolish more of the old eastern section before final construction.[96] As of December 2016, the path is open only on weekends and holidays from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. "to ensure public safety during torch cutting and other old Bay Bridge demolition activities".[97] On May 2, 2017, public access was extended to seven days a week, 6 a.m. to 9 p.m.,[98] with occasional closure days for continued demolition of the old bridge foundations.[99] This work was completed on November 11, 2017.[100]

Financing and tolls

Two-way collection

When the Bay Bridge opened in 1936, the toll was 65 cents,[58] collected in each direction by men in booths fronting each lane of traffic. Within months, the toll was lowered to 50 cents in order to compete with the ferry system, and finally to 25 cents since this was shown sufficient to pay off the original revenue bonds on schedule. In 1951 there were eighty collectors working various shifts.[101]

One-way collection

On Monday, September 1, 1969, (Labor Day) a change of policy resulted in the toll being collected thereafter only from westbound traffic, at twice the previous rate; eastbound vehicles were toll-exempt.[102]

Tolls were subsequently raised to finance improvements to the bridge approaches, required to connect with new freeways, and to subsidize public transit in order to reduce the traffic over the bridge.

Caltrans, the state highway transportation agency, maintains seven of the eight San Francisco Bay Area bridges. (The Golden Gate Bridge is owned and maintained by the Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District.)

The basic toll (for automobiles) on the seven state bridges was raised to $1 by Regional Measure 1, approved by Bay Area voters in 1988.[103] A $1 seismic retrofit surcharge was added in 1998 by the state legislature, originally for eight years, but since then extended to December 2037 (AB1171, October 2001).[104] On March 2, 2004, voters approved Regional Measure 2, raising the toll by another dollar to a total of $3. An additional dollar was added to the toll starting January 1, 2007, to cover cost overruns concerning the replacement of the eastern span.

The Metropolitan Transportation Commission, a regional transportation agency, in its capacity as the Bay Area Toll Authority, administers RM1 and RM2 funds, a significant portion of which are allocated to public transit capital improvements and operating subsidies in the transportation corridors served by the bridges. Caltrans administers the "second dollar" seismic surcharge, and receives some of the MTC-administered funds to perform other maintenance work on the bridges. The Bay Area Toll Authority is made up of appointed officials put in place by various city and county governments, and is not subject to direct voter oversight.[105]

Due to further funding shortages for seismic retrofit projects, the Bay Area Toll Authority again raised tolls on all Bay Area bridges in its control (this excludes the Golden Gate Bridge) in July 2010.[106] The toll rate for autos on other Bay Area bridges was increased to $5, but in the Bay Bridge a variable pricing tolling scheme based on congestion was implemented. The Bay Bridge congestion pricing scheme charges a $6 toll from 5 a.m. to 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. to 7 p.m., Monday through Friday. During weekends cars pay $5. Carpools before the implementation were exempted but now they pay $2.50, and the carpool toll discount is now also available only to drivers with FasTrak electronic toll devices. The toll remained at the previous toll of $4 at all other times on weekdays.[107][108] The Bay Area Toll Authority reported that by October 2010 fewer users are driving during the peak hours and more vehicles are crossing the Bay Bridge before and after the 5–10 a.m. period in which the congestion toll goes into effect. Commute delays in the first six months dropped by an average of 15% compared with 2009.[109][110] For vehicles with at least 3 axles, the toll rate is $5 per axle.[111]

In June 2018, Bay Area voters approved Regional Measure 3 to further raise the tolls on all seven of the state-owned bridges to fund $4.5 billion worth of transportation improvements in the area.[112][113] Under the passed measure, the tolls on the Bay Bridge will be raised by $1 on January 1, 2019, then again on January 1, 2022, and again on January 1, 2025. Thus under the congestion pricing scheme, the tolls for autos during the peak weekday rush hours will be $7 in 2019, $8 in 2022, and $9 in 2025; for the non-rush periods, $5 in 2019, $6 in 2022, and $7 in 2025; and on weekends, $6 in 2019, $7 in 2022, and $8 in 2025.[114]

In September 2019, the MTC approved a $4 million plan to eliminate toll takers and convert all seven of the state-owned bridges to all-electronic tolling, citing that 80 percent of drivers are now using Fastrak and the change would improve traffic flow.[115] On March 20, 2020, at midnight, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all-electronic tolling was temporarily placed in effect for all seven state-owned toll bridges.[116]

Notes

- "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form". National Park Service – USDoI. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge Archived November 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "Traffic Census Program". California Department of Transportation. 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

Traffic Volumes: Annual Average Daily Traffic

- "San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge". Metropolitan Transportation Commission. Bay Area Toll Authority. 2014–15. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

45.5 million toll-paid vehicles (91.0 million trips) annually

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "San Francisco Oakland Bay Bridge (West)". Structurae. Nicolas Janberg. May 12, 2006. Retrieved August 8, 2008.

- "San Francisco Oakland Bay Bridge (East)". Structurae. Nicolas Janberg. February 28, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2008.

- 2008 Named Freeways, Highways, Structures and Other Appurtenances in California (PDF). California Department of Transportation. January 2009. p. 41. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 23, 2013.

- "First Cars Cross SF-Oakland Bay Bridge's New Span". ABC News. Retrieved September 3, 2013.

- Jaffe, Eric (October 13, 2015). "From $250 Million to $6.5 Billion: The Bay Bridge Cost Overrun". CityLab. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- "San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge wins Excellence in Structural Engineering honor". Press releases. California Department of Transportation. September 15, 2014.

- "Old Bay Bridge Demolition". California Department of Transportation.

- "San Francisco Oakland Bay Bridge". Bay Bridge Public Information Office. September 8, 2009. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- "Self-Anchored Suspension (SAS) Span". Caltrans. Archived from the original on October 26, 2010. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

Anticipated Completion Date: late 2013

- "Yerba Buena Crossing (Contract No. 04-5) – As Built Drawings" Caltrans 2006

- Richards, Gary (December 5, 2008). "From the Two Trees to the Sig Sanchez: Bay Area road nicknames explained". San Jose Mercury News. Bay Area News Group. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- "Rebounding Economy Prompts Rise in Freeway Congestion" (Press release). Metropolitan Transportation Commission. September 14, 2005. Archived from the original on November 2, 2010. Retrieved July 12, 2008.

- "Caltrans District 4 Bicycle Resources". California Department of Transportation. July 14, 2008. Archived from the original on November 22, 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- "Complimentary to Selby, Ralston and Otis". San Francisco Real Estate Circular. April 1872. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- Herel, Suzanne (December 15, 2004). "Emperor Norton's name may yet span the bay". San Francisco Chronicle. pp. A–1. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2008.

- Crane, Lorin P. (April 1913). "Proposed Suspension Bridge Over San Francisco Bay". Overland Monthly. 61 (4): 375–77.

- "The San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge Facts at a glance". Caltrans toll bridge program. California Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on November 3, 2010. Retrieved July 12, 2008.

- Statutes of California, 48th Session, 1929, Chaps. 762-3, p.1489

- California Highways and Public Works, May-June, 1929, p.15

- California Highways and Public Works, December, 1930, p.8

- U.S. Statutes at Large, 71st Congress, Chap.238, pp.1192-3

- [California Highways and Public Works, February, 1932, p.22]

- California Highways and Public Works, November, 1936, p.12

- "Aerial photographs of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge Approaches-1931", Fairchild Aerial Surveys Inc.

- California Highways and Public Works, June, 1931, p.5

- California Highways and Public Works, October, 1931, p.12

- California Highways and Public Works, April, 1932, p.22

- "Spectacular Job at Bottom of Sea; 10 Boals, 33 Men Remove Phone Cables", California Highways and Public Works, July, 1931, p.12-13

- "Billions for Building". Time. XXII (4). New York. July 24, 1933. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- "Building the Bay Bridge: 1930s vs. today". August 9, 2013.

- Leboski, pp. 339–40

- "World's Largest Bridge rest on sunken skyscrapers" Popular Science, February 1935

- Petroski, p. 340

- Reisner, p. 113

- "The old Transbay Terminal: When trains came first", San Mateo Daily Journal online edition, September 24, 2018

- California Highways and Public Works, November, 1936, p.27

- "'Great Fill and Wall for Bay Bridge Approach", California Highways and Public Works, Dec. 1933, p.13

- State of California, Dept. of Public Works, Tunnel Section and Details, Yerba Buena Crossing, San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, June 1934, Sup. Drawing No. 19A, PDF p.28

- kevinsyoza (July 3, 2010). "San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge Lower Deck Eastbound Drive California" – via YouTube.

- "Two Bay Area Bridges". U.S. Department of Transportation. January 18, 2005. Archived from the original on October 11, 2009. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- "Caltrans Facts/Information". Caltrans. Archived from the original on April 7, 2007. Retrieved February 4, 2007.

- "Commemoratives | Classic Commemorative Silver and Gold (1936) San Francisco Oakland Bay Bridge Opening | Coin Value Guide". whitman.com. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- Ford, Robert S. Red Trains in the East Bay (1977) Interurbans Publications ISBN 978-0-916374-27-3 p.258

- "New Bay Bridge on-off ramps to Treasure Island now open". ABC 7 News San Francisco Oakland San Jose. ABC 7 News. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- Swenerton, Jeff. "When Trains Ruled the East Bay".

- "Building Bay Bridge Railroad", California Highways and Public Works, v.16 no.5, May, 1938, pp.8-11

- Red Trains in the East Bay, Robert Ford, Interurbans Special 65, 1977

- The Key Route, Harre Demoro, Interurbans Special 95, 1985

- Bernard McGloin, John (1978). San Francisco, the Story of a City. San Francisco (California): Presidio Press. ISBN 978-0-89141-045-4.

- "Jet Smashes Into Bay Span". Lodi News-Sentinel. United Press International. February 12, 1968. p. 1.

- "Bay Bridge rammed by Navy jet trainer". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Associated Press. February 12, 1968. p. 2.

- "The Battle of the Bay Bridge". Check-Six.com. 2002. Archived from the original on October 19, 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "East Span News". California Department of Transportation. May 2002. Archived from the original on May 25, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- Wollan, Malia (March 4, 2013). "Long-Overshadowed Bay Bridge Will Go From Drab Gray to Glowing". The New York Times.

- Egelko, Bob (December 17, 2014). "Bay Bridge light show will go on". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 31, 2014. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

... the nonprofit Illuminate the Arts announced Wednesday that it had raised the needed $4 million to reinstall the "Bay Lights" as a permanent fixture on the western end of the bridge.

- Cuff, Denis (January 28, 2016). "Bay Bridge light sculpture turns back on Saturday night". Contra Costa Times. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- The Bay Lights (thebaylights.org)

- Bay Bridge light display dazzles San Francisco Includes video (following a too-long advertisement)

- "Bay Area transit agencies push for bus-only lane on Bay Bridge". KTVU. January 18, 2020.

- Joe Fitzgerald Rodriguez (February 21, 2020). "Lawmaker introduces legislation to kick off creation of Bay Bridge bus lane". San Francisco Examiner.

- "Historic Earthquakes". United States Geological Survey. January 25, 2008. Archived from the original on September 11, 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- Ali Khan, Mohiuddin (August 12, 2014). Accelerated Bridge Construction: Best Practices and Techniques (1 ed.). Elsevier. p. 282. ISBN 9780124072244. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- "BICYCLE AND PEDESTRIAN PATH | Bay Bridge Info". baybridgeinfo.org. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- Cabanatuan, Michael (September 13, 2013). "Bay Bridge eastern span opens". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Cabanatuan, Michael (January 28, 2014). "Demolition crews start chipping away at old Bay Bridge". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- "Demolition of Bay Bridge's old eastern span completed". Bay City News Service. November 11, 2017. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- DiGiacomo, Janet (September 6, 2009). "Officials: Crack may keep Bay Bridge closed past Tuesday". San Francisco, California: CNN. Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. Retrieved September 6, 2009.

- Dearen, Jason; Sudhin Thanawala (October 28, 2009). "Bay Bridge failure stirs fear, anger over new span". San Francisco Examiner. Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- "Emergency repair and detour connection completed on Bay Bridge". Press Release. Bay Bridge Public Information Office. September 8, 2009. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- Michael Cabanatuan; Jaxon Van Derbeken; Jill Tucker; Carolyn Jones (October 29, 2009). "Bridge parts couldn't take the wind". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 4, 2010.

- Bay Bridge Closed for Eyebar Assessment and Repair Caltrans. Retrieved October 29, 2009. Archived November 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- photograph of bridge damage by commuter directly behind it Archived October 31, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Bay Bridge closed indefinitely. KGO-TV-7 ABC7News. October 28, 2009, 9:33 pm.

- Marshall, John; Leff, Lisa (October 28, 2009). "Tough commute likely after Bay Bridge rod snaps". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- Jason Dearin; Sudhin Thanawala (October 28, 2009). "No estimate when Bay Bridge will open". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 30, 2009.

- Michael Cabanatuan; Justin Berton (October 28, 2009). "Bay Bridge closed after repair falls apart". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 25, 2010.

- "Bay Bridge will remain closed for 'a few days'". Los Angeles Times. October 28, 2009. Archived from the original on October 29, 2009.

- Jones, Carolyn (November 2, 2009). "Bay Bridge stays closed". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 6, 2010.

- Denis Cuff; Janis Mara (October 28, 2009). "Extra ferry, BART trains planned for morning commute". Contra Costa Times. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011.

- KSBW Action News Sunrise (5-7am), October 28, 2009

- "Named Freeways, Highways, Structures and Other Appurtenances in California", California Department of Transportation, 2013, p. 43.

- The Emperor's Bridge Campaign, "Emperor Norton's Bridge Proclamations".

- The Emperor's Bridge Campaign, "1939 Plaque". Archived October 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- The Emperor's Bridge Campaign, "Naming Efforts". Archived October 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Resolution in Support of the Emperor Norton Bridge, introduced to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors by District 3 Supervisor Aaron Peskin, 2004. Archived December 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- California Legislature, 2013–14 Regular Session, Assembly Concurrent Resolution No. 65 – Relative to the Willie L. Brown, Jr. Bridge, June 12, 2013.

- Justin Slaughter, "Petition to name Bay Bridge after Emperor Norton gains 1,000 signatures", San Francisco Bay Guardian, August 13, 2013.

- Official California Legislative Information, "Documents associated with ACR 65", Legislative Counsel of California.

- "Behold the Willie L. Brown Jr. Bridge". KQED News. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- "Bicycle Die-Hards Test Out Bay Bridge Bike Path". NBC News. September 3, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- "No longer the Bay Bridge Trail to nowhere". SFGate. October 23, 2016. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- "BICYCLE AND PEDESTRIAN PATH - Bay Bridge Info". www.baybridgeinfo.org.

- "Bay Bridge bike path has new $2 million 'vista point;' will open seven days a week starting Tuesday". The Mercury News. April 29, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- "Bicycle and Pedestrian Path". California Department of Transportation. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- "Old Bay Bridge Demolition". California Department of Transportation. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- C.H. Garrigues, "Most Polite Man," Nation's Business, February 1951, pages 72-74

- "One-Way Tolls to Start Monday on All Bridges," The Argus, Fremont, California, August 29, 1969, image 5

- Regional Measure 1 Toll Bridge Program. bata.mtc.ca.gov; Bay Area Toll Authority. Archived November 4, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Dutra, John (October 14, 2001). "AB 1171 Assembly Bill – Chaptered". California State Assembly. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- "About MTC". Metropolitan Transportation Commission. October 15, 2009. Archived from the original on November 3, 2010. Retrieved October 15, 2009.

- "Frequently Asked Toll Questions". Bay Area Toll Authority. June 1, 2010. Archived from the original on November 22, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- "Toll Increase Information". Bay Area Toll Authority. June 1, 2010. Archived from the original on October 23, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- Michael Cabanatuan (May 13, 2010). "Reminder: Bridge tolls go up July 1". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- Michael Cabanatuan (January 12, 2011). "Conflicting findings on Bay Bridge congestion toll". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- "Bay Bridge Traffic Decreases After Congestion Pricing". CBS News San Francisco. January 12, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- "Toll Increase Information: Multi-Axle Vehicles". Bay Area Toll Authority. July 1, 2012. Archived from the original on December 30, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- Cabanatuan, Michael (June 6, 2018). "Regional Measure 3: Work on transportation improvements could start next year". SFGate.com.

- Kafton, Christien (November 28, 2018). "Bay Area bridge tolls to increase one dollar in January, except Golden Gate". KTVU.

- "Tolls on Seven Bay Area Bridges Set to Rise Next Month" (Press release). Metropolitan Transportation Commission. December 11, 2018. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- Smith, Darrell (September 7, 2019). "Do you drive to the Bay Area? A big change is coming to toll booths at the bridges". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "Cash Toll Collection Suspended at Bay Area Bridges". Metropolitan Transportation Commission. March 20, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

References

- "Findings and Recommendation For Completion of the Main Span of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge East Span Seismic Safety Project" (PDF). Toll Bridge Seismic Retrofit Program. California Department of Transportation. December 8, 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 25, 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- Petroski, Henry. (1995). Engineers of Dreams: Great Bridge Builders and the Spanning of America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-679-43939-0.

- Reisner, Marc (1999). A Dangerous Place: California's Unsettling Fate. Penguin Books.

- Russell, Ron (March 17, 2004). "A Bridge Too Weak?". SF Weekly. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge East Span Seismic Safety Project. Retrieved August 24, 2005.

External links

![]()

Official sites:

- baybridgeinfo.org Site by Caltrans about all current construction on the bridge.

- California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) official Bay Bridge site

Journals:

- "San Francisco To Have World's Greatest Bridges". Popular Science: 25–26. March 1931.

- White, Tom (January 1933). "The Titan Of Bridges". Popular Mechanics: 10–14.

- "Giant Switchboard Controls Lights on Longest Bridge". Popular Mechanics: 42. January 1937.

Media:

- "Building the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge (1937 documentary)" on YouTube (17 minutes)

- "EarthCam San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge Construction time-lapse" on YouTube

- Lower Deck Rail and Roadway Off Ramps, 1939, Dorothea Lange photo

- San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge Construction Collection MSS 722.

- Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Library.

- "Bridging San Francisco Bay", PDH Online Course C577

Other:

- Bay Bridge Oral History Project, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley

- "Symphonies in Steel: Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate" at The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

- "New Bay Bridge". Archived from the original on August 19, 2007.

- San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge (West Span) at Structurae

- San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge (Old East Span) at Structurae

- San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge (New East Span) at Structurae

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. CA-32, "San Francisco Oakland Bay Bridge", 415 photos, 20 measured drawings, 273 data pages, 48 photo caption pages

- HAER No. CA-230, "San Francisco Oakland Bay Bridge Firehouse", 1 photo, 2 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- Live Toll Prices for San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge

.jpg)