Geothermal energy in the United States

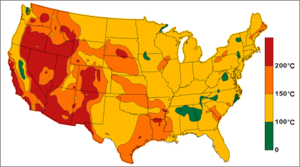

Geothermal energy in the United States was first used for electric power production in 1960. The Geysers in Sonoma and Lake counties, California was developed into what is now the largest geothermal steam electrical plant in the world, at 1,517 megawatts. Other geothermal steam fields are known in the western United States and Alaska. Geothermally generated electric power can be dispatchable to follow the demands of changing loads. Environmental impact of this energy source includes hydrogen sulfide emissions, corrosive or saline chemicals discharged in waste water, possible seismic effects from water injection into rock formations, waste heat and noise.

History

According to archaeological evidence, geothermal resources have been in use on the current territory of the United States for more than 10,000 years. The Paleo-Indians first used geothermal hot springs for warmth, cleansing, and minerals.[1]

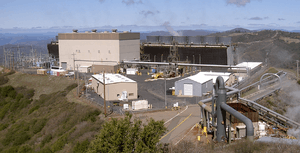

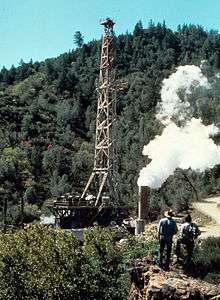

The first commercial geothermal power plant producing power to the U.S. utility grid opened at The Geysers in California in September 1960, producing eleven megawatts of net power. The Geysers system continues to operate successfully today, and the complex has grown into the largest geothermal development in the world, with an output of 750 MW.[1] The largest dry steam field in the world is the Geysers, 116 km (72 mi) north of San Francisco. It was here that Pacific Gas and Electric began operation of the first successful geothermal electric power plant in the United States in 1960.[2] The original turbine lasted for more than 30 years and produced 11 MW net power.[3] The Geysers has 1517 megawatt (MW)[4] of active installed capacity with an average capacity factor of 63%.[5] Calpine Corporation owns 15 of the 18 active plants in the Geysers and is currently the United States' largest producer of geothermal energy.[6] Two other plants are owned jointly by the Northern California Power Agency and the City of Santa Clara's municipal Electric Utility (now called Silicon Valley Power). The remaining Bottle Rock Power plant owned by the US Renewables Group has only recently been reopened.[7] A nineteenth plant is now under development by Ram Power, formerly Western Geopower. Since the activities of one geothermal plant affects those nearby, the consolidation plant ownership at The Geysers has been beneficial because the plants operate cooperatively instead of in their own short-term interest. The Geysers is now recharged by injecting treated sewage effluent from the City of Santa Rosa and the Lake County sewage treatment plant. This sewage effluent used to be dumped into rivers and streams and is now piped to the geothermal field where it replenishes the steam produced for power generation.

Another major geothermal area is located in south central California, on the southeast side of the Salton Sea, near the cities of Niland and Calipatria, California. In 2001, there were 15 geothermal plants producing electricity in the area. CalEnergy owns about half of them and the rest are owned by various companies. Combined the plants have a capacity of about 570 MW. Hudson Ranch I geothermal plant, a 50 MW plant opened in May 2012, the first in the area in 20 years. A second similar plant is to open in 2013.[8]

The Basin and Range geologic province in Nevada, southeastern Oregon, southwestern Idaho, Arizona and western Utah is now an area of rapid geothermal development. Several small power plants were built during the late 1980s during times of high power prices. Rising energy costs have spurred new development. The capacity of all 19 currently active geothermal power plants in Nevada is more than 486 MW. The largest plant is the McGinnis Hills facility operated by Ormat with a capacity of 96MW. [9]Other geothermal plants in Nevada are at Steamboat Springs, Brady/Desert Peak, Dixie Valley, Soda Lake, Stillwater and Beowawe.

Production

With 3,676 MW of installed geothermal capacity as of 2019, the United States remains the world leader with about 25% of the online capacity total.[10][11][12] The future outlook for expanded production from conventional and enhanced geothermal systems is positive as new technologies promise increased growth in locations previously not considered.[13]

Research and development

As of August 2008, 103 new projects are under way in 13 U.S. states. When developed, these projects could potentially supply up to 3,979 MW of power, meeting the needs of about 4 million homes. At this rate of development, geothermal production in the United States could exceed 15,000 MW by 2025.[13]

The most significant catalyst behind new industry activity is the Energy Policy Act of 2005. This Act made new geothermal plants eligible for the full federal production tax credit, previously available only to wind power projects and certain kinds of biomass. It also authorized and directed increased funding for research by the Department of Energy, and enabled the Bureau of Land Management to address its backlog of geothermal leases and permits.[16]

In April 2008, exploratory drilling began at Newberry Volcano in Oregon.[17]

In 2009, investment bank Credit Suisse calculated that geothermal power costs 3.6 cents per kilowatt-hour, versus 5.5 cents per kilowatt-hour for coal, if geothermal receives loans with lower rates than offered by the market."[18]

A report released in late May 2019 by the Department of Energy suggests that U.S. geothermal power capacity could increase by more than twenty-six times by 2050, reaching a total installed capacity of 60 GW, thanks to accelerated technological development and adoption. (Also see figure on the left.) The report also demonstrates the benefits of geothermal power for residential and industrial heating.[19] Energy Secretary Rick Perry announced his Department had provided funding for a $140-million research facility at the University of Utah on man-made geothermal energy.[20]

Reliability

Unlike some other renewable power sources such as wind and solar, geothermal energy is dispatchable, meaning that it is both available whenever needed, and can quickly adjust output to match demand. According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), of all types of new electrical generation plants, geothermal generators have the highest capacity factor, a measure of how much power a facility actually generates as a percent of its maximum capacity. The EIA rates new geothermal plants as having a 92% capacity factor, comparable to those of nuclear (90%), and higher than gas (87%), or coal (85%), and much higher than those of intermittent sources such as onshore wind (34%) or solar photovoltaic (25%).[21] While the carrier medium for geothermal electricity (water) must be properly managed, the source of geothermal energy, the Earth's heat, will be available, for most intents and purposes, indefinitely.[1][22]

In 2008 the USDOE funded research in Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) to learn more about the fracture systems in geothermal reservoirs and better predict the results of reservoir stimulation. The DOE Geothermal Technologies Program (part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009) provided funding to establish the National Geothermal Data System (NGDS). Through the NGDS, many older paper archives and drill logs that are stored at state geological surveys are now being digitized and made available for free to the public.[23]

Environmental effects

The underground hot water and steam used to generate geothermal power may contain chemicals that could pollute the air and water if released at the surface.

Hydrogen sulfide, which is toxic in high concentrations, is sometimes found in geothermal systems.[24] Newer methods of generating geothermal power separate the hot steam collected underground from the steam used to power turbines, and substantially reduce the risk of releasing air-polluting contaminants.[25]

The water mixed with the steam contains dissolved salts that can damage pipes and harm aquatic ecosystems.[26] Some subsurface water associated with geothermal sources contain high concentrations of toxic elements such as boron, lead, and arsenic.

Injection of water in enhanced geothermal systems may cause induced seismicity. Earthquakes at the Geysers geothermal field in California, the largest being Richter magnitude 4.6, have been linked to injected water.[27]

"Possible effects include scenery spoliation, drying out of hot springs, soil erosion, noise pollution, and chemical pollution of the atmosphere and of surface- and groundwaters."[28]

Due to volcanic activities the Puna Geothermal Venture had to be closed and was affected by lava flows later.[29]

See also

- Aquaculture

- Biofuel in the United States

- Geothermal desalination

- Geothermal Energy Association

- Geothermal Resources Council

- Hydroelectric power in the United States

- List of renewable energy topics by country

- Renewable energy in the United States

- Solar power in the United States

- Wind power in the United States

References

- A Guide to Geothermal Energy and the Environment Archived 2007-10-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Lund, J. (September 2004), "100 Years of Geothermal Power Production" (PDF), Geo-Heat Centre Quarterly Bulletin, Klamath Falls, Oregon: Oregon Institute of Technology, 25 (3), pp. 11–19, ISSN 0276-1084, retrieved 2009-04-13

- McLarty, Lynn; Reed, Marshall J. (October 1992). "The U.S. Geothermal Industry: Three Decades of Growth" (PDF). Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects. London: Taylor & Francis. 14 (4): 443–455. doi:10.1080/00908319208908739. ISSN 1556-7230. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-16.

- DiPippo, Ronald (2008). Geothermal Power Plants, Second Edition: Principles, Applications, Case Studies and Environmental Impact. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-8620-4.

- Lund, John W.; Bloomquist, R. Gordon; Boyd, Tonya L.; Renner, Joel (24–29 April 2005), "The United States of America Country Update" (PDF), Proceedings World Geothermal Congress, Antalya, Turkey, retrieved 2009-11-09 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - All figures adjusted to include recently reopened Bottle Rock Power plant.

- Baker, David R. (January 14, 2007). "Steamy industry may clear the air". San Francisco Chronicle. Lake County. p. F-1. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- 49.9-MW Hudson Ranch I Geothermal Plant Unveiled in California, Meg Cichon, RenewableEnergyWorld.com

- "Geothermal Resources". NV Energy. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- "Geothermal Industry Update March" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-04-19. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- "Top 10 Geothermal Countries based on installed capacity – Year End 2017".

- "Top 10 Geothermal Countries based on installed capacity – Year End 2019".

- Update: The State of U.S. Geothermal Production and Development

- "2012 Annual US Geothermal Power Production and Development Report" (PDF). Geothermal Energy Association. February 2013.

- Danko, Pete. New Mexico joins the geothermal power ranks. Geothermal Power. Renewable Energy. Earth Techling. http://www.earthtechling.com/2014/01/new-mexico-joins-the-geothermal-power-ranks/. Accessed 6 February 2014.

- 6 Million American Households to be Powered by Geothermal Energy, New Survey Reports Archived 2007-05-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Gail Kinsey-Hill (2008-06-03). "Company Seeks Power From Crater". Vancouver Sun. p. B2.

- Christopher Mims “Can Geothermal Power Compete with Coal on Price?” Scientific American, 2 March 2009. Web. 9 Oct. 2009.

- "DOE Releases New Study Highlighting the Untapped Potential of Geothermal Energy in the United States". U.S. Department of Energy. May 30, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- McCombs, Brady (May 30, 2019). "Trump administration doubles down on fossil fuels". Associated Press (via LA Times). Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- US Energy Information Administration, Levelized cost of new generation resources, Annual Energy Outlook 2013, 15 April 2013.

- Geothermal 101: Basics of Geothermal Energy Production and Use p. 5 & 7. Archived March 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "New Geothermal Data System Could Open Up Clean-Energy Reserves". Scientific American, William Ferguson on February 25, 2013

- McFarland, Ernest L. “Geothermal Energy.” Macmillan Encyclopedia of Energy. Ed. Ed John Zumerchik. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2001. 572-579. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 9 Oct. 2009.

- Raser Technologies - How Modular Geothermal Power Generation Works Archived 2011-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- “Alternative Energy Sources.” UXL Encyclopedia of Science. Ed. Rob Nagel. 2nd ed. Detroit: UXL, 2007. Student Resource Center Gold. Web. 9 Oct. 2009.

- Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, The Geysers

- Arnórsson, Stefán (2004). "Environmental impact of geothermal energy utilization". Special Publications. The Geological Society of London. 236: 297–336. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2004.236.01.18. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- http://www.staradvertiser.com/2018/05/27/breaking-news/lava-speeds-up-takes-aim-at-puna-geothermal-wells/

External links

- GA Mansoori, N Enayati, LB Agyarko (2016), Energy: Sources, Utilization, Legislation, Sustainability, Illinois as Model State, World Sci. Pub. Co., ISBN 978-981-4704-00-7

- Geothermal Energy Association

- Geothermal Resources Council

- Geothermal Lease Auction Signals New Trend in U.S.

- The Status of the U.S. Geothermal Industry

- Scaling Geothermal for Reliable Baseload Power

- Technological Innovation Driving Renewed Interest in Geothermal Energy

- Interior Department To Open 190 Million Acres to Geothermal Power

- Raser Ready to Deliver Power from Thermo Plant

- A History of Geothermal Energy in the United States

- Geothermal energy prospect in the United States

- Hawaii Groundwater & Geothermal Resources Center by the University of Hawaii at Manoa

- The Geothermal Collection by UH Manoa

- M 5.0 - 8km NW of The Geysers, California – United States Geological Survey