Public good (economics)

In economics, a public good (also known as a social good or collective good) is a good that is both non-excludable and non-rivalrous, in that individuals cannot be excluded from use or could benefit from without paying for it, and where use by one individual does not reduce availability to others or the good can be used simultaneously by more than one person.[1] This is in contrast to a common good such as wild fish stocks in the ocean, which is non-excludable but is rivalrous to a certain degree, as if too many fish are harvested, the stocks will be depleted.

Public goods include knowledge, official statistics, national security, common language(s), flood control systems, lighthouses, and street lighting. Public goods that are available everywhere are sometimes referred to as global public goods.[2] Examples of public good knowledge is men's, women's and youth health awareness, environmental issues, maintaining biodiversity, sharing and interpreting contemporary history with a cultural lexicon, particularly about protected cultural heritage sites and monuments, popular and entertaining tourist attractions, libraries and universities.

Many public goods may at times be subject to excessive use resulting in negative externalities affecting all users; for example air pollution and traffic congestion. Public goods problems are often closely related to the "free-rider" problem, in which people not paying for the good may continue to access it. Thus, the good may be under-produced, overused or degraded.[3] Public goods may also become subject to restrictions on access and may then be considered to be club goods; exclusion mechanisms include toll roads, congestion pricing, and pay television with an encoded signal that can be decrypted only by paid subscribers.

There is a good deal of debate and literature on how to measure the significance of public goods problems in an economy, and to identify the best remedies.

Terminology, and types of goods

Paul A. Samuelson is usually credited as the economist who articulated the modern theory of public goods in a mathematical formalism, building on earlier work of Wicksell and Lindahl. In his classic 1954 paper The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure,[4] he defined a public good, or as he called it in the paper a "collective consumption good", as follows:

[goods] which all enjoy in common in the sense that each individual's consumption of such a good leads to no subtractions from any other individual's consumption of that good...

This is the property that has become known as non-rivalry. A pure public good exhibits a second property called non-excludability: that is, it is impossible to exclude any individuals from consuming the good.

However, many goods may satisfy the two public good conditions (non-rivalry and non-excludability) only to a certain extent or only some of the time. These goods are known as impure public goods.

The opposite of a public good is a private good, which does not possess these properties. A loaf of bread, for example, is a private good; its owner can exclude others from using it, and once it has been consumed, it cannot be used by others.

A good that is rivalrous but non-excludable is sometimes called a common-pool resource. Such goods raise similar issues to public goods: the mirror to the public goods problem for this case is the 'tragedy of the commons'. For example, it is so difficult to enforce restrictions on deep-sea fishing that the world's fish stocks can be seen as a non-excludable resource, but one which is finite and diminishing.

Definition matrix

| Excludable | Non-excludable | |

| Rivalrous | Private goods food, clothing, cars, parking spaces |

Common-pool resources fish stocks, timber, coal |

| Non-rivalrous | Club goods cinemas, private parks, satellite television |

Public goods free-to-air television, air, national defense |

Elinor Ostrom proposed additional modifications to the classification of goods to identify fundamental differences that affect the incentives facing individuals[5]

- Replacing the term "rivalry of consumption" with "subtractability of use".

- Conceptualizing subtractability of use and excludability to vary from low to high rather than characterizing them as either present or absent.

- Overtly adding a very important fourth type of good—common-pool resources—that shares the attribute of subtractability with private goods and difficulty of exclusion with public goods. Forests, water systems, fisheries, and the global atmosphere are all common-pool resources of immense importance for the survival of humans on this earth.

- Changing the name of a "club" good to a "toll" good since many goods that share these characteristics are provided by small scale public as well as private associations.

Challenges in identifying public goods

The definition of non-excludability states that it is impossible to exclude individuals from consumption. Technology now allows radio or TV broadcasts to be encrypted such that persons without a special decoder are excluded from the broadcast. Many forms of information goods have characteristics of public goods. For example, a poem can be read by many people without reducing the consumption of that good by others; in this sense, it is non-rivalrous. Similarly, the information in most patents can be used by any party without reducing consumption of that good by others. Official statistics provide a clear example of information goods that are public goods, since they are created to be non-excludable. Creative works may be excludable in some circumstances, however: the individual who wrote the poem may decline to share it with others by not publishing it. Copyrights and patents both encourage the creation of such non-rival goods by providing temporary monopolies, or, in the terminology of public goods, providing a legal mechanism to enforce excludability for a limited period of time. For public goods, the "lost revenue" of the producer of the good is not part of the definition: a public good is a good whose consumption does not reduce any other's consumption of that good.[6]

Debate has been generated among economists whether such a category of "public goods" exists. Steven Shavell has suggested the following:

when professional economists talk about public goods they do not mean that there are a general category of goods that share the same economic characteristics, manifest the same dysfunctions, and that may thus benefit from pretty similar corrective solutions...there is merely an infinite series of particular problems (some of overproduction, some of underproduction, and so on), each with a particular solution that cannot be deduced from the theory, but that instead would depend on local empirical factors.[7]

There is a common misconception that public goods are goods provided by the public sector. Although it is often the case that government is involved in producing public goods, this is not always true. Public goods may be naturally available, or they may be produced by private individuals, by firms, or by non-state groups, called collective action.[8]

The theoretical concept of public goods does not distinguish geographic region in regards to how a good may be produced or consumed. However, some theorists, such as Inge Kaul, use the term "global public good" for a public good which is non-rivalrous and non-excludable throughout the whole world, as opposed to a public good which exists in just one national area. Knowledge has been argued as an example of a global public good,[9] but also as a commons, the knowledge commons.[10]

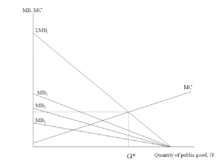

Graphically, non-rivalry means that if each of several individuals has a demand curve for a public good, then the individual demand curves are summed vertically to get the aggregate demand curve for the public good. This is in contrast to the procedure for deriving the aggregate demand for a private good, where individual demands are summed horizontally.

Some writers have used the term "public good" to refer only to non-excludable "pure public goods" and refer to excludable public goods as "club goods".[11]

Examples

Common examples of public goods include: defence, public fireworks, lighthouses, clean air and other environmental goods, and information goods, such as official statistics, open-source software, authorship, public television and radio, and invention. Some goods, like orphan drugs, require special governmental incentives to be produced, but cannot be classified as public goods since they do not fulfill the above requirements (non-excludable and non-rivalrous.) Law enforcement, streets, libraries, museums, and education are commonly misclassified as public goods, but they are technically classified in economic terms as quasi-public goods because excludability is possible, but they do still fit some of the characteristics of public goods.[12][13]

The provision of a lighthouse is a standard example of a public good, since it is difficult to exclude ships from using its services. No ship's use detracts from that of others, but since most of the benefit of a lighthouse accrues to ships using particular ports, lighthouse maintenance can be profitably bundled with port fees (Ronald Coase, The Lighthouse in Economics 1974). This has been sufficient to fund actual lighthouses.

Technological progress can create new public goods. The most simple examples are street lights, which are relatively recent inventions (by historical standards). One person's enjoyment of them does not detract from other persons' enjoyment, and it currently would be prohibitively expensive to charge individuals separately for the amount of light they presumably use. Official statistics are another example. The government's ability to collect, process and provide high-quality information to guide decision-making at all levels has been strongly advanced by technological progress. On the other hand, a public good's status may change over time. Technological progress can significantly impact excludability of traditional public goods: encryption allows broadcasters to sell individual access to their programming. The costs for electronic road pricing have fallen dramatically, paving the way for detailed billing based on actual use.

Some question whether defense is a public good. Murray Rothbard argues:

"'national defense' is surely not an absolute good with only one unit of supply. It consists of specific resources committed in certain definite and concrete ways—and these resources are necessarily scarce. A ring of defense bases around New York, for example, cuts down the amount possibly available around San Francisco."[14]

Jeffrey Rogers Hummel and Don Lavoie note,

"Americans in Alaska and Hawaii could very easily be excluded from the U.S. government's defense perimeter, and doing so might enhance the military value of at least conventional U.S. forces to Americans in the other forty-eight states. But, in general, an additional ICBM in the U.S. arsenal can simultaneously protect everyone within the country without diminishing its services".[15]

Public goods are not restricted to human beings.[16] It is one aspect of the study of cooperation in biology.[17]

Free rider problem

Public goods are often associated with the free rider problem, a form of market failure, in which market-like behavior of individual gain-seeking does not produce economically efficient results. The production of public goods results in positive externalities which are not remunerated. If private organizations do not reap all the benefits of a public good which they have produced, their incentives to produce it voluntarily might be insufficient. Consumers can take advantage of public goods without contributing sufficiently to their creation. This is called the free rider problem, or occasionally, the "easy rider problem" (because consumers' contributions will be small but non-zero). If too many consumers decide to "free-ride", private costs exceed private benefits and the incentive to provide the good or service through the market disappears. The market thus fails to provide a good or service for which there is a need.[18]

The free rider problem depends on a conception of the human being as homo economicus: purely rational and also purely selfish—extremely individualistic, considering only those benefits and costs that directly affect him or her. Public goods give such a person an incentive to be a free rider.

For example, consider national defense, a standard example of a pure public good. Suppose homo economicus thinks about exerting some extra effort to defend the nation. The benefits to the individual of this effort would be very low, since the benefits would be distributed among all of the millions of other people in the country. There is also a very high possibility that he or she could get injured or killed during the course of his or her military service.

On the other hand, the free rider knows that he or she cannot be excluded from the benefits of national defense, regardless of whether he or she contributes to it. There is also no way that these benefits can be split up and distributed as individual parcels to people. The free rider would not voluntarily exert any extra effort, unless there is some inherent pleasure or material reward for doing so (for example, money paid by the government, as with an all-volunteer army or mercenaries). The free-riding problem is even more complicated than it was thought to be until recently. Any time non-excludability results in failure to pay the true marginal value (often called the "demand revelation problem"), it will also result in failure to generate proper income levels, since households will not give up valuable leisure if they cannot individually increment a good.[19] This implies that, for public goods without strong special interest support, under-provision is likely since benefit-cost analyses are being conducted at the wrong income levels, and all of the ungenerated income would have been spent on the public good, apart from general equilibrium considerations.

In the case of information goods, an inventor of a new product may benefit all of society, but hardly anyone is willing to pay for the invention if they can benefit from it for free. In the case of an information good, however, because of its characteristics of non-excludability and also because of almost zero reproduction costs, commoditization is difficult and not always efficient even from a neoclassical economic point of view.[20]

Efficient production levels of public goods

The Pareto optimal provision of a public good in a society occurs when the sum of the marginal valuations of the public good (taken across all individuals) is equal to the marginal cost of providing that public good. These marginal valuations are, formally, marginal rates of substitution relative to some reference private good, and the marginal cost is a marginal rate of transformation that describes how much of that private good it costs to produce an incremental unit of the public good.) This contrasts to the Pareto optimality condition of private goods, which equates each consumer's valuation of the private good to its marginal cost of production.[4][21]

For an example, consider a community of just two consumers and the government is considering whether or not to build a public park. One person is prepared to pay up to $200 for its use, while the other is willing to pay up to $100. The total value to the two individuals of having the park is $300. If it can be produced for $225, there is a $75 surplus to maintaining the park, since it provides services that the community values at $300 at a cost of only $225.

The classical theory of public goods defines efficiency under idealized conditions of complete information, a situation already acknowledged in Wicksell (1896).[22] Samuelson emphasized that this poses problems for the efficient provision of public goods in practice and the assessment of an efficient Lindahl tax to finance public goods, because individuals have incentives to underreport how much they value public goods.[4] Subsequent work, especially in mechanism design and the theory of public finance developed how valuations and costs could actually be elicited in practical conditions of incomplete information, using devices such as the Vickrey–Clarke–Groves mechanism. Thus, deeper analysis of problems of public goods motivated much work that is at at the heart of modern economic theory.[23]

Local public goods

The basic theory of public goods as discussed above begins with situations where the level of a public good (e.g., quality of the air) is equally experienced by everyone. However, in many important situations of interest, the incidence of benefits and costs is not so simple. For example, when people keep an office clean or monitor a neighborhood for signs of trouble, the benefits of that effort accrue to some people (those in their neighborhoods) more than to others. The overlapping structure of these neighborhoods is often modeled as a network.[24] (When neighborhoods are totally separate, i.e., non-overlapping, the standard model is the Tiebout model.)

Recently, economists have developed the theory of local public goods with overlapping neighborhoods, or public goods in networks: both their efficient provision, and how much can be provided voluntarily in a noncooperative equilibrium. When it comes to efficient provision, networks that are more dense or close-knit in terms of how much people can benefit each other have more scope for improving on an inefficient status quo.[25] However, voluntary provision is typically below the efficient level, and equilibrium outcomes tend to involve strong specialization, with a few individuals contributing heavily and their neighbors free-riding on those contributions.[24][26]

Ownership

An important question regarding public goods is whether they should be owned by the public or the private sector. Economic theorists such as Oliver Hart (1995) argue that ownership matters for investment incentives when contracts are incomplete.[27] The incomplete contracting paradigm has been applied to public goods by Besley and Ghatak (2001).[28] They consider the government and a non-governmental organization (NGO) who can both make investments to provide a public good. Besley and Ghatak show that the party who has a larger valuation for the public good should be the owner, regardless of whether the government or the NGO has a better investment technology. This result contrasts with the case of private goods studied by Hart (1995), where the party with the better investment technology should be the owner. However, more recently it has been shown that the investment technology matters also in the public-good case when a party is indispensable or when there are bargaining frictions between the government and the NGO.[29][30]

See also

- Lindahl tax, a method proposed by Erik Lindahl for financing public goods

- Private-collective model of innovation, which explains the creation of public goods by private investors

- Public bad

- Public goods game, a standard of experimental economics

- Public works, government-financed constructions

- Tragedy of the anticommons

- Anti-rival good

- Rivalry (economics)

- Quadratic funding, a mechanism to allocate funding for the production of public goods based on democratic principles

References

- For current definitions of public goods see any mainstream microeconomics textbook, e.g.: Hal R. Varian, Microeconomic Analysis ISBN 0-393-95735-7; Andreu Mas-Colell, Whinston & Green, Microeconomic Theory ISBN 0-19-507340-1; or Gravelle & Rees, Microeconomics ISBN 0-582-40487-8.

- Cowen, Tyler (December 2007). David R. Henderson (ed.). The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Public Goods. The Library of Economics and Liberty. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- Rittenberg and Tregarthen. Principles of Microeconomics, Chapter 6, Section 4. p. 2 Archived 19 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 20 June 2012

- Samuelson, Paul A. (1954). "The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure". Review of Economics and Statistics. 36 (4): 387–89. doi:10.2307/1925895. JSTOR 1925895.

See also Samuelson, Paul A. (1955). "Diagrammatic Exposition of a Theory of Public Expenditure". Review of Economics and Statistics. 37 (4): 350–56. doi:10.2307/1925849. JSTOR 1925849. - Elinor, Ostrom (2005). Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Demsetz, Harold (October 1970). "Full Access The Private Production of Public Goods". Journal of Law and Economics. 13 (2): 293–306. doi:10.1086/466695. JSTOR 229060.

- Boyle, James (1996). Shamans, Software, and Spleens: Law and the Construction of the Information Society. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. pp. 268. ISBN 978-0-674-80522-4.

- Touffut, J.P. (2006). Advancing Public Goods. The Cournot Centre for Economic Studies. Edward Elgar Publishing, Incorporated. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-84720-184-3. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Joseph E. Stiglitz, "Knowledge as a Global Public Good" in Global Public Goods, ISBN 978-0-19-513052-2

- Hess, Charlotte; Ostrom, Elinor (2007). Understanding Knowledge as a Commons: From Theory to Practice. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-262-08357-7.

- James M. Buchanan (February 1965). "An Economic Theory of Clubs". Economica. 32 (125): 1–14. doi:10.2307/2552442. JSTOR 2552442.

- Pucciarelli F., Andreas Kaplan (2016) Competition and Strategy in Higher Education: Managing Complexity and Uncertainty, Business Horizons, Volume 59

- Campbell R. McConnell; Stanley L. Brue; Sean M. Flynn (2011). Economics: Principles, Problems, and Policies (19th ed.). McGraw-Hill/Irwin. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-07-351144-3.

- "Books / Digital Text". Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Hummel, Jeffrey Rogers & Lavoie, Don. "National Defense and the Public-Goods Problem". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Julou, Thomas; Mora, Thierry; et al. (2013). "Cell–cell contacts confine public goods diffusion inside Pseudomonas aeruginosa clonal microcolonies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (31): 12–577–12582. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11012577J. doi:10.1073/pnas.1301428110. PMC 3732961. PMID 23858453.

- West SA, Griffin AS, Gardner A (2007). "Evolutionary explanations for cooperation". Current Biology. 17 (16): R661–R672. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.004. PMID 17714660.

- Ray Powell (June 2008). "10: Private goods, public goods and externalities". AQA AS Economics (paperback ed.). Philip Allan. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-340-94750-0.

- Graves, P. E., "A Note on the Valuation of Collective Goods: Overlooked Input Market Free Riding for Non-Individually Incrementable Goods Archived 30 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine", The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 9.1 (2009).

- Babe, Robert (1995). "Chapter 3". Essay in Information, Public Policy and Political Economy. University of Ottawa: Westview Press.

- Brown, C. V.; Jackson, P. M. (1986), "The Economic Analysis of Public Goods", Public Sector Economics, 3rd Edition, Chapter 3, pp. 48–79.

- Wicksell, Knut (1958). "A New Principle of Just Taxation". In Musgrave and Peackock (ed.). Classics in the Theory of Public Finance. London: Macmillan.

- Maskin, Eric (8 December 2007). "Mechanism Design: How to Implement Social Goals" (PDF). Nobel Prize Lecture.

- Bramoullé, Yann; Kranton, Rachel (July 2007). "Public goods in networks". Journal of Economic Theory. 135 (1): 478–494. doi:10.1016/j.jet.2006.06.006.

- Elliott, Matthew; Golub, Benjamin (2019). "A Network Approach to Public Goods". Journal of Political Economy. 127 (2): 730–776. doi:10.1086/701032. ISSN 0022-3808.

- Galeotti, Andrea; Goyal, Sanjeev (September 2010). "The Law of the Few". American Economic Review. 100 (4): 1468–1492. doi:10.1257/aer.100.4.1468. ISSN 0002-8282.

- Hart, Oliver (1995). Firms, Contracts, and Financial Structure. Oxford University Press.

- Besley, Timothy; Ghatak, Maitreesh (2001). "Government Versus Private Ownership of Public Goods". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 116 (4): 1343–72. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.584.6739. doi:10.1162/003355301753265598. ISSN 0033-5533.

- Halonen-Akatwijuka, Maija (2012). "Nature of human capital, technology and ownership of public goods". Journal of Public Economics. Fiscal Federalism. 96 (11–12): 939–45. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.173.3797. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.07.005.

- Schmitz, Patrick W. (2015). "Government versus private ownership of public goods: The role of bargaining frictions". Journal of Public Economics. 132: 23–31. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2015.09.009.

Bibliography

- Coase, Ronald (1974). "The Lighthouse in Economics". Journal of Law and Economics. 17 (2): 357–376. doi:10.1086/466796.

Further reading

- Acoella, Nicola (2006), ‘Distributive issues in the provision and use of global public goods’, in: ‘Studi economici’, 88(1): 23-42.

- Lipsey, Richard (2008). "Economics" (11): 281–283. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Zittrain, Jonathan, The Future of the Internet: And How to Stop It. 2008

- Lessig, Lawrence, Code 2.0, Chapter 7, What Things Regulate

External links

| Library resources about Public good (economics) |

- Public Goods: A Brief Introduction, by The Linux Information Project (LINFO)

- Cowen, Tyler (2008). "Public Goods". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0-86597-665-8. OCLC 237794267.

- Global Public Goods – analysis from Global Policy Forum

- The Nature of Public Goods

- Hardin, Russell, "The Free Rider Problem", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2013 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)