Immigration to Sweden

Immigration to Sweden is the process by which people migrate to Sweden to reside in the country. Many, but not all, become Swedish citizens. The economic, social, and political aspects of immigration have caused some controversy regarding ethnicity, economic benefits, jobs for non-immigrants, settlement patterns, impact on upward social mobility, crime, and voting behaviour.

_annual_Immigration_and_Emigration_2000-2017.png)

Sweden had very few immigrants in 1900 when the nationwide population totaled 5,100,814 inhabitants, of whom 35,627 individuals were foreign-born (0.7%). 21,496 of those foreign-born residents were from other Nordic countries, 8,531 people were from other European countries, 5,254 from North America, 90 from South America, 87 from Asia, 79 from Africa, and 59 from Oceania.[2]

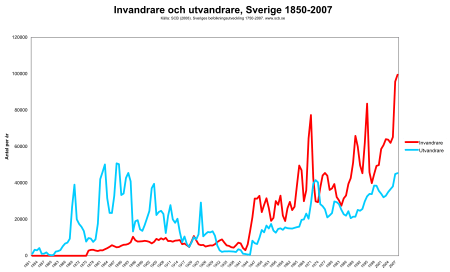

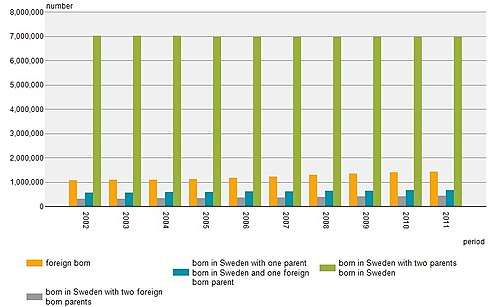

As of 2010, 1.33 million people or 14.3% of the inhabitants of Sweden were foreign-born. Of these individuals, 859,000 (64.6%) were born outside the European Union and 477,000 (35.4%) were born in another EU member state.[3] Sweden has evolved from a nation of net emigration ending after World War I to a nation of net immigration from World War II onward. In 2013, immigration reached its highest level since records began, with 115,845 people migrating to Sweden while the total population grew by 88,971.[4][5] It continued to rise steadily the following years, followed by a clear peak with just over 163,000 persons immigrating in total that year – 2017 was a decrease, with nearly 144,500 individuals immigrating.[5] As of 2017, the percentage inhabitants with a foreign background in Sweden had risen to 24.1%.[6] The official definition of foreign background (sv:utländsk bakgrund) comprises individuals either born abroad or having both parents born abroad.[6] In 2017, majorities in three municipalities had foreign backgrounds: Botkyrka (58.6%) Södertälje (53.0%) and Haparanda (51.7%).[6]

In 2014, 81,300 individuals applied for asylum in Sweden, which was an increase of 50% compared to 2013 and the most since 1992. 47% of them came from Syria, followed by 21% from the Horn of Africa (mostly Eritrea and Somalia). 77% (63,000) requests were approved but it differs greatly between different groups. Nearly two weeks into October 2015, a record figure of 86,223 asylum applications was reached, and in the remaining weeks of the year that figure rose to 162,877. In 2016, 28,939 people applied for asylum,[7] after temporary border ID controls had been initiated and been in effect during 2016.[8] As of 2014, according to Statistics Sweden, there was around 17,000 total asylum immigrants from Syria, 10,000 from Iraq, 4,500 from Eritrea, 1,900 from Afghanistan, and 1,100 from Somalia.[9] In the year 2017, most asylum seekers come from Syria (267), Eritrea (263), Iraq (117), and Georgia (106).[10]

According to an official report by the governmental Swedish Pensions Agency, total immigration to Sweden for 2017 was expected to be roughly 180,000 individuals, and thereafter to number 110,000 persons every year.[11][12]

Immigrants in Sweden are mostly concentrated in the urban areas of Svealand and Götaland. The largest foreign-born populations residing in Sweden come from Finland, Iraq, the former Yugoslavia, Poland, Iran, and Syria.

History

Before the second world war, Sweden was a linguistically and culturally homogeneous country compared with other European countries with the exception of the Sami and Tornedalian minorities.[13] During the High Middle Ages, German immigrants arrived as foreign experts in trade and mining and are estimated to have constituted 10-20% of the city populations. However, since only 5% of the population lived in cities during this time their total share of the populated was only 1 to 1.5% of the population. Small, but influential, numbers of Walloon immigrants started arriving in the 17th century and again in the 19th century. Most of them returned to Belgium after a few years and the estimates for how many that stayed range from 900 to 2000 compared with the contemporary population of Sweden being 900 000.[14]

- World War II

| Population by country of birth 1900-2016 | |

| |

| The figure shows the percentage of the population who were born in Sweden and conversely the first generation immigrant's share of the total population. Source: Statistics Sweden.[15] | |

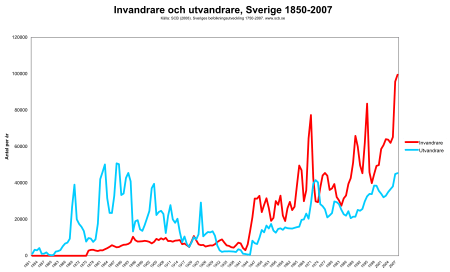

From 1871 and onwards Statistics Sweden reports the number of immigrants each year. From 1871 to 1940 the average number of immigrants were 6000 per year.[14] Immigration increased markedly with World War II. Historically, the most numerous of foreign born nationalities are ethnic Germans from Germany and other Scandinavians from Denmark and Norway. In short order, 70,000 war children were evacuated from Finland, of which 15,000 remained in Sweden. Also, many of Denmark's nearly 7,000 Jews who were evacuated to Sweden decided to remain there.

A sizable community from the Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) arrived during the Second World War.[16]

- 1945 to 1967

As of 1945, the immigrants share of the population was below 2%.[14] During the 1950s and 1960s, the recruitment of migrant workers was an important factor of immigration. The Nordic countries signed a trade agreement in 1952, establishing a common labour market and free movement across borders. This migration within the Nordic countries, especially from Finland to Scandinavia, was essential to create the tax-base required for the expansion of the strong public sector now characteristic of Scandinavia. Facing pressure from unions, work force immigration from outside of the Nordic countries was limited by new laws in 1967.[17]

On a smaller scale, Sweden took in political refugees from Hungary and the former Czechoslovakia after their countries were invaded by the Soviet Union in 1956 and 1968 respectively. Some tens of thousands of American draft dodgers from the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 1970s also found refuge in Sweden.

- 1968–1991

In the latter half of the 1960s, the ideology of multiculturalism entered the political mainstream in Sweden, the first country in Europe. On 14 May 1975, a unanimous Swedish parliament led by the Social Democrat government of Olof Palme voted in favour on a new immigrant and minority policy which explicitly rejected the previous policy of assimilation and ethno-cultural homogeneity in favour of state-sponsored multiculturalism.[18] The main driver of spreading Islam in Sweden is immigration since the late 1960s.[19] As of 1970, the immigrants share of the population was below 7%.[14] The demand for labor within the production industry declined and many Finns that had moved to Sweden in the late 1960s started to return to Finland. The period between 1970 and 1985 can be seen as a transition period from an immigration based on labor to an immigration based on refugee.[17] Especially from former Yugoslavia (due to the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s) but also from countries in the Middle East and Latin America.[20] After seeing a number of refugees in the first half of 1989 (20 000), Carlsson I Cabinet decided to limit refugee immigration to only include refugees by the definition of United Nations.

Contemporary immigration

Beginning in 2008, there was a long-term shift in the countries of origin, with a larger share of migrants with low education from non-European countries.[21]

In 2009, immigration reached its highest level since records began with 102,280 people migrating to Sweden while the total population grew by 84,335[22] – in 2012 a new highest level was reached, again in 2013, and by a large margin again in 2016.[23] At the same time, in 2016 the number of asylum applicants fell from the 2015 record of over 162,800, to 28,939, and 25,666 in 2017.[24]

In 2010, 32,000 people applied for asylum to Sweden, a 25% increase from 2009, one of the highest numbers in Sweden since 1992 and the Balkan wars.[25] The number of people that were granted asylum stayed the same as previous years. In 2009, Sweden had the fourth-largest number of asylum applications in the EU and the largest number per capita after Cyprus and Malta.[26]

During 2010 the most common reason for immigrating to Sweden was:

- Labour migrants (21%)

- Family reunification (20%)

- Immigrating under the EU/EES rules of free movement (18%)

- Students (14%)

- Refugees (12%)[27]

In 2010, 32,000 people applied for asylum to Sweden, a 25% increase from 2009; however, the number of people who received asylum did not increase because the large increase was in large part due to allowing Serbian nationals to travel without a visa to Sweden.[25] Sweden has the highest asylum immigration per million inhabitants in Europe.

The number of asylum seekers coming to Sweden increased beginning in 2014. 81,300 applied for asylum in 2014, which was an increase of 50% compared to 2013. It was the most since 1992, when 84,018 persons applied for asylum during the war in Yugoslavia. 77% (63,000) requests were approved but it differed greatly between different groups, such as Syrians and Eritreans where nearly everyone gets their application approved.[28] In February 2015, it was expected that 90,000 apply for asylum in 2015 and 80,000 in 2016. The Swedish Migration Agency currently has shortage of 15,000 accommodations so they have to rent from private actors.[29] At the end of April 2015, the figure for the year 2015 was revised down to 68,000–88,000 with 80,000 as the main scenario. Long processing times, and the situation in Iraq not developing in the way the Swedish Migration Agency had feared was the reason for the revised figures.[30] Nearly two weeks into October 2015, 86,223 had applied for asylum so far during the year. That was a record, surpassing the 1992 figure of 84,018 during the war in Yugoslavia. Emergency accommodation such as drill halls or offices were needed.[31][32] All in all, 162,877 applied for asylum that year,[33] many of which were processed after 2015, due to handling times. As of 2014, according to Statistics Sweden, there were around 17,000 total asylum immigrants from Syria (an increase of ~16,000 from 1990), 10,000 from Iraq (an increase of ~6,000 from 1990), 4,500 from Eritrea (an increase of ~4,400 from 1990), 1,900 from Afghanistan (an increase of ~1,800 from 1990), and 1,100 from Somalia (an increase of ~300 from 1990).[9] In the year 2017, most asylum seekers came from Syria (267), Eritrea (263), Iraq (117), and Georgia (106).[10]

A series of violent riots starting with the 2008 Malmö mosque riots and including the 2009 Malmö anti-Israel riots, 2010 Rinkeby riots, 2013 Stockholm riots, 2016 Sweden riots and 2017 Rinkeby riots, during which groups made up mostly of young immigrants torched cars and buildings and threw rocks at police, led many Swedes to question Sweden's ability to integrate migrants.[34]

During the refugee crisis of 2015, 29% of Swedes polled in September thought that Sweden was taking too many refugees – in November 2015, that figure had risen to 41%.[35]

Among people receiving residence permits in Sweden during 2009–2017, 55.2% were men or boys, and 44.8% women or girls.[36]

The four largest and most well known Swedish newspapers reported more negative than positive news about immigration in the years 2010–2015.[37] The reporting in other Swedish media outlets may not have offered a less negative picture of immigration to Sweden.[38]

In March 2016, the production crew of the Australian TV program 60 Minutes were assaulted in Rinkeby when they were reporting the effect of European refugee crisis.[39] The same month, Norway's minister of migration Sylvi Listhaug said to Norwegian media that Norway must avoid becoming like Sweden, in terms of immigration.[40]

In April 2016, Reuters reported that at least 70 married girls under 18 were living in asylum centres in Stockholm and Malmö. Reuters added: "In Sweden, the lowest age for sex is 15 and marriage 18."[41]

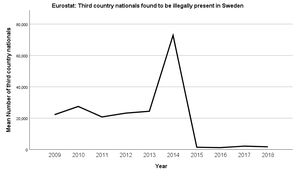

In June 2017, the Supreme Administrative Court of Sweden (HFD) ruled that illegal immigrants, such as those who stay in hiding after their asylum applications had been rejected in order to evade deportation, had no right to welfare benefits. A woman who was denied welfare benefits (försörjningsstöd, in Swedish) by the council of Vännäs had taken the council to court. The first instance ruled in the woman's favour, but the council took the case to the highest court, HFD, which ruled in favour of the council.[42]

According to an age-testing investigation in August 2017 by The National Board of Forensic Medicine, 82% of immigrants suspected to be above 18 and who claim to be under are determined to be above 18.[43]

According to a 2017 Swedish Police Authority report on organised crime in Sweden, in autumn 2015, the number of asylum applicants to Sweden had markedly risen. The police authorities indicate that most of these asylum seekers had arrived via people smugglers, with compatriots smuggling compatriots being the most common scenario. Police authorities estimated that the smugglers charged several hundred thousand SEK. Many of the smuggled asylum seekers owed substantial debts to the traffickers, which left them vulnerable to exploitation by organised crime.[44]

Data indicates that the smuggling networks would capitalize on the right of asylum seekers to establish their own housing (EBO) instead of accommodation organized by the Swedish Migration Agency. The smuggling networks would thereby organize accommodation for the smuggled in especially vulnerable areas, where the traffickers already had contacts in place. The traffickers thus exploit asylum seekers by using them as cheap or free labor, coercing them into under-the-table work, and siphoning off their welfare benefits.[45]

Demographics

Current population of immigrants and their descendants

There are no exact numbers on the ethnic background of migrants and their descendants in Sweden as the Swedish state does not base any statistics on ethnicity. This is, however, not to be confused with the migrants' national backgrounds which are being recorded.

In 2016, 1,784,497 residents were foreign born, 535,805 were born in Sweden to two parents born abroad, 739,813 had one parent born abroad and 6,935,038 had no foreign born parents. Statistics Sweden counts people born abroad or with two parents born abroad as having a foreign background, 2,320,302 persons met that requirement.[46]

According to Statistics Sweden, as of 2016, there are a total of 400,203 residents of Sweden who hold citizenship from European Union states and other countries in Europe, 273,787 from countries in Asia, and 110,758 from countries in Africa.[47]

According to Statistics Sweden, as of 2016, there is a total of 8,541 foreign-born children and young adults aged 0–21 who are adopted in Sweden. Of these individuals, the most common countries of birth are China (3,977), South Korea (1,735), Colombia (1,438), Vietnam (1,241), and India (1,017).[48]

Immigrants from specific countries are divided into several ethnic groups. For example, there are both Turks and Kurds from Turkey, Arabs and Berbers from Morocco, Russians and Chechens from Russia, and immigrants from Iran are divided into Persians, Azeris, Kurds and Lurs.[49]

Note that the table below lists the citizenship the person had when arriving in Sweden and therefore there are no registered Eritreans, Russians or Bosnians from 1990, they were recorded as Ethiopians, Soviets and Yugoslavs. The nationality of Yugoslavs below is therefore people who came to Sweden from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia before 1991 and people who came from today's Montenegro and Serbia before 2003, then called the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Counting all people who came from Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, Kosovo, Macedonia, Serbia and Montenegro, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, there were 176,033 people from there in 2018.

| Country | 1900 | 1930 | 1960 | 1990 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | − | 6 | 5,874 | 191,530 | |

| − | − | 16 | 9,818 | 146,048 | |

| 6,644 | 9,746 | 101,307 | 217,636 | 144,561 | |

| − | 1,065 | 6,347 | 35,631 | 93,722 | |

| 2 | 8 | 115 | 40,084 | 80,136 | |

| − | − | − | 1,441 | 70,173 | |

| − | 19 | 1,532 | 43,346 | 64,349 | |

| − | − | − | − | 60,012 | |

| − | − | 17 | 534 | 58,780 | |

| 15 | 22 | 202 | 25,528 | 51,689 | |

| 5,107 | 8,566 | 37,580 | 37,558 | 51,436 | |

| − | − | − | − | 45,734 | |

| − | − | 20 | 4,934 | 43,556 | |

| 7,978 | 14,731 | 37,253 | 52,744 | 41,578 | |

| 45 | 135 | 361 | 9,054 | 40,641 | |

| 6,872 | 8,726 | 35,112 | 43,931 | 39,457 | |

| 34 | 201 | 520 | 3,896 | 35,282 | |

| 3 | 34 | 719 | 8,785 | 32,294 | |

| 779 | 1,270 | 2,738 | 11,378 | 29,979 | |

| − | − | 15 | 15,986 | 28,508 | |

| 6 | 28 | 69 | 27,635 | 28,025 | |

| 5,130 | 8,852 | 10,874 | 13,001 | 22,802 | |

| 1,506 | − | − | − | 22,265 | |

| 5 | − | 59 | 10,027 | 21,686 | |

| − | − | 1 | 6,265 | 20,676 | |

| 5 | 22 | 266 | 13,171 | 19,547 | |

| − | − | 11 | 2,291 | 19,107 | |

| 50 | 108 | 8,544 | 15,045 | 16,728 | |

| − | 149 | − | 233 | 15,596 | |

| − | − | 5 | 2,613 | 15,281 | |

| Total immigrant population | 35 627 | 61 657 | 299 879 | 790 445 | 2 019 733 |

| Region | Population |

|---|---|

| Western Asia | 392,539 |

| Northern Europe | 301,926 |

| Southern Europe | 215,089 |

| Eastern Europe | 183,318 |

| Eastern Africa | 133,181 |

| Southern Asia | 88,780 |

| Western Europe | 83,943 |

| Southeastern Asia | 78,133 |

| South America | 69,645 |

| Eastern Asia | 48,847 |

| Northern Africa | 33,044 |

| Northern America | 23,771 |

| Western Africa | 18,502 |

| Central America | 8,978 |

| Central Asia | 7,493 |

| Middle Africa | 6,982 |

| Oceania | 5,575 |

| Caribbean | 4,709 |

| Southern Africa | 3,049 |

Changing gender demographics

Record keeping for gender demographics began in 1749 in Sweden; at first, the country tended to have more women than men, but in 2015, Sweden became a nation with more men than women. Between March 2015 and May 2016, the disparity between men and women changed from 277 to a startling 12,000.[52] A similar trend began in Norway in 2011. For Sweden, this has mostly been attributed to two factors: firstly, the increasing male life expectancy, as there is already a natural birth rate of around 105 males for every 100 females. The second factor is the role that immigrants have been playing in Sweden's demographics; in 2015, immigration accounted for 77% of Sweden's 103,662 population surplus.[53] In particular, unaccompanied male teen immigrants are having a tremendous impact; in 2015, Sweden had a record-breaking number of unaccompanied immigrants – 35,000.[52] With one birth in Sweden every four minutes, one death every six, and one net migrant over 13, the male population surplus is predicted to reach even higher numbers in the years to come.[54]

Employment

| Unemployment among low-educated in Sweden 2005–2016 aged 20–64, per region of birth | |

| |

| Statistics Sweden: The labour market for persons with a lower level of education 2005–2016[55] | |

According to statistics collected by OECD, Sweden had in 2014 the highest negative gap in its employment rate between native and foreign-born population of the 28 OECD countries surveyed.[56] This was for populations with both high and low education. Non-European immigrants with low education (sv: förgymnasial utbildning) of ages 20–64 had an unemployment rate of about 31.7% in 2005 which rose to 36.9% in 2016.[57]

Employment disparities

Sweden and the Netherlands have strong economies, but they have also the widest employment rate gaps between immigrants and non-immigrants of all OECD states.[60] Before 163,000 asylum seekers that arrived in Sweden in 2015, the difference in employment rate was around 15% for those in between the ages of 15–64. For Swedes, 79% of this age group were employed while it was a mere 64% for foreign-born residents. When comparing native-born Swedes to non-EU immigrants, the employment gap between the two groups is even higher at 22.5%.[61] This is in contrast with the U.S., where native-born Americans are around 2.5% more likely to be unemployed than immigrants.[60]

There are a couple speculations as to why Sweden is an anomaly in these arenas. First of all, between 2003 and 2012, one fifth of the permanent migrants into Sweden were considered humanitarian migrants. This is a higher percentage than all other OECD countries and likely plays a role in the employment gaps as humanitarian migrants typically find it more difficult to integrate into OECD countries.[62] Second of all, less than 5% of jobs in Sweden require only a high school degree.[60] With migrants from Syria and Iraq almost certainly having never studied Swedish back home, it is inevitably difficult for them to find work. Considering they are among the top three countries of immigrant origin alongside Finland, correlation between their employment rates and that of all Swedish migrants is high.

Of the 163,000 asylum seekers in 2015, 500 were employed. Asylum seekers are, however, not automatically granted a work permit, with one third of working-age asylum seekers having received an exception to the work/residence permit requirement.[63][64]

The report "När blir utrikesfödda självförsörjande?" by Professor Johan Eklund and Lecturer Johan P. Larsson at the Swedish Entrepreneurship Forum shows that a majority of the foreign-born in Sweden during the period 1990 to 2016 have not become self-sufficient with respect to earnings. The results differ from the official statistics, which do not differentiate between part-time and full-time employment. Individuals of working age, 20–64 years, who achieve half of the median income were included, as this is defined as the lower limit for self-sufficiency. According to this study, the self-sufficiency of domestic-born Swedes was 73 percent in 2016, whereas the corresponding proportion for individuals born in Africa was 38 percent, and 36 percent for those born in the Middle East. The report pointed out that this measurement method still overestimates the degree of self-sufficiency of migrants, since it does not exclude jobs that are tax-financed through labor market initiatives which thus constitute a form of social security.[65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72]

Effects of immigration

Public finances

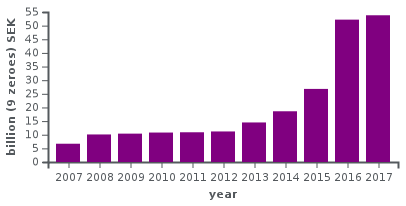

| Swedish Migration Agency annual expenditure SEK (2007–) | |

| |

| Billion (109) SEK. Expenditure is Område 8 and Område 13 According to table Redovisning mot anslag Column Utgifter for each year in the annual reports.[73] | |

Several studies have been made on immigrants' net contribution to the public sector. With the low immigrant unemployment rate and a smaller share of the total population, the studies concluded that immigrant net contribution to the public sector was either negligible, neutral or slightly positive up until the 1970s. With increasing unemployment rates and a larger share of the total population, this was shown no longer to be true in 1999 by Ekberg.[74] More recent studies such as Ruist show that the cost of refugees were 1% of GDP in 2007 and Aldén & Hammarstedt show that the average cost of a refugee that had been living in Sweden for five years was 120,000 SEK per year.[75][76]

In 2015, Sweden received 163,000 asylum seekers and spent €6 billion (1.35% of GDP) on its migrants that year.[77]

According to the Swedish National Audit Office, changes in the volume and composition of people seeking or being granted residence permit has significant consequences to the finances and organisations of public institutions administered by the state and municipalities. When the number of applications rise, there are nearly instantaneous volume effects for the expenses in the migration section of the government budget. The expenses concern mainly extended administration of residence application by the Swedish Migration Agency and courts, reimbursing municipalities for lodging and welfare benefits to asylum seekers. Since some grants to asylum seekers and expenses for lodging are payable during the application process, the expenses are affected by the duration of the asylum process.[78]

|

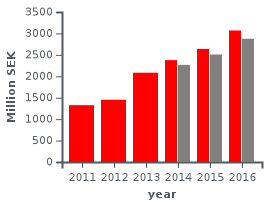

Expenses of publicly funded SFI, million SEK. (red: Skolverket, grey: Municipalities etc) | |

| |

| Y-axis in million 106 krona (SEK). Source: Swedish National Agency for Education (red)[79] 2011,[80] 2012,[81] 2013,[82] 2014,[83] 2015,[84] 2016[85] Municipalities & private organisers (grey)[86] No SCB Data for municipalities prior to 2014. | |

The state budget for migration expenses increased fivefold from 6997 million SEK in 2004 to 33896 million in 2015, not counting the expenses for the European migrant crisis in the autumn of 2015.[87] In the same 2004–2015, government forecasts consistently underestimated migration costs for migration (sv: Utgiftsområde 8 Migration) by several billion (109) annually.[88] Whereas the volume of immigration directly affects public expenses, 11 out of 26 government propositions in the 2004–2015 time period neglected to predict or analyse the consequences of policy changes with regards to changes in numbers. In a further 11 propositions, the proposal is stated to not impact the numbers arriving without any reason given.[89] In 16 propositions, no investigation for costs for municipalities is performed.[90]

The impact of immigration is, however, not limited to the migration section in the budget. First generation immigrants, for example, constituted 60% of economic welfare recipients in 2016, 73% of all unemployed and 53% of those serving long prison sentences.[91][92][93]

In a calculation made by The Swedish Pensions Agency, immigrants were expected to generate additional 70 billion SEK to the pension system thanks to the increased number of people working, but also add 150 billion SEK in costs.[94] According to an official investigation in 2017, immigration to Sweden will double the state's expenses for pensions to the population.[11][12] A 2018 paper argued that refugee immigration had a net negative fiscal impact, both in the short and long-term, with effects being highest in the first few years. Over time refugees make a positive fiscal contribution but this is not enough to cover the initial deficit and the deficit that appears as they approach retirement age.[95] A 2019 paper examined whether immigration could support Sweden's ageing population. The paper concluded, based on current labour market integration, that GDP per capita and public finance would not be improved sufficiently to compensate for an ageing population. However, immigrants could potentially bring large growth gains if labour market integration was improved significantly.[96]

Demographics

Immigration has had a significant effect on the demographics of Sweden. Since World War II, Sweden has - like other developed nations - turned into a country with a low fertility rate. Due to the high birthrates in the early post-war years and the steep decline in the late 20th century, Sweden has one of the oldest populations in the world. In 2009, 102,280 immigrants entered Sweden, while the total population grew by 84,335.[22]

According to the Sweden Democrats, the high immigration rate, low fertility and high death rate is gradually transforming the previously homogeneous nation of Sweden into a multicultural country. The party criticised the country's current immigration policies, claiming that they can pose a major demographic threat to Sweden in the future. In 2011, it was expected that the Muslim minority in Sweden would grow from 5% to 10% by 2030.[97]

Crime

Those with an immigrant background are over-represented in Swedish crime statistics, but research shows that socioeconomic factors, such as unemployment, poverty, exclusion language, and other skills explain most of the differences in crime rates between immigrants and natives.[98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105][106]

A 1996 report by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (Brå) explored crime among immigrants and children of immigrants between 1985 and 1989, compared to the rest of the Swedish population. The tendency, according to the report, was that the more serious the crime, the higher number of reported crimes had a foreign born perpetrator. The highest shares was in rape, with 38% of registered perpetrators being foreign-born, murder and manslaughter at 30%, 26% of thefts in stores, 24% of robberies, and 20–21% of physical abuse cases. The general over-representation in crime for foreign-born individuals was 2.2; for individual categories highest values was found in physical abuse against unfamiliar man, with 4.7 (see note in reference), and with rape 4.0 (standardized values with effects of age, sex and residence area eliminated). 88% of immigrants hadn't been registered for any sort of crime at all. Children of immigrants were also over-represented in crime, but to a much lesser degree – 50% higher in general compared to non-immigrant Swedes. In physical abuse against an unfamiliar man, the standardized over-representation was 3.2, the highest for the group, and in rape, 1.5.[107] The share of foreign born individuals guilty or suspected of rape was less than 0.3% according to a 2005 report by Brå.[108] Both the 1996 and 2005 reports have been criticized for using insufficient controls for socioeconomic factors.[98]

| 2013–2018 birthplace of rapists convicted in Sweden | |

| |

| Total: 843. Source: Swedish Television[109] | |

In 2018, Swedish television's investigative journalism show Uppdrag Granskning (UG) analysed the total of 843 district court cases from the five preceding years resulting in convictions and found that 58% of all convicted of rape had a foreign background and 40% were born in the Middle East and Africa, with young men from Afghanistan numbering 45 stood out as being the most next most common country of birth after Sweden. When only analysing rape assault (Swedish: överfallsvåldtäkt) cases, that is cases where perpetrator and victim were not previously acquainted, 97 out of 129 were born outside Europe.[109] The BBC, reporting on the Uppdrag Granskning episode, emphasized that only a very small number of rapes resulted in convictions, and there was no data available on the ethnicity of perpetrators in the 6,000–7,000 rapes per year reported between 2009 and 2017 which had not gone to court. The BBC also asked the chief editor of Uppdrag Granskning why they had aired a potentially inflammatory episode just before the 2018 Swedish general election: the response was that immigration was a major issue for every political party in Sweden, and Swedes needed an understanding of their own country.[110]

In a 2016 report on sexual harassment, police found ten cases where groups of men (aged 25–30) or boys (aged 14–16) had surrounded a lone girl and sexually assaulted her while filming, along with groups of girls being subjected to the same experience. Only a few perpetrators were identified, and all investigations in Stockholm and Kalmar involved suspects from Afghanistan, Eritrea or Somalia. Most intestigations were dropped due to difficulty in identifying the perpetrators and collecting evidence.[111]

After criticism arose that Sweden was experiencing an increase in crime due to immigrants and refugees, Jerzy Sarnecki, a criminologist at Stockholm University, claimed, "What we're hearing is a very, very extreme exaggeration based on a few isolated events, and the claim that it's related to immigration is more or less not true at all."[112][113] According to Klara Selin, a sociologist at the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (Brottsförebyggande rådet), abbreviated Brå, the major reasons why Sweden has a higher rate of rape than other countries is due to the way in which Sweden documents rape ("if a woman reports being raped multiple times by her husband that's recorded as multiple rapes, for instance, not just one report") and a culture where women are encouraged to report rapes.[112] Stina Holmberg at Brå noted that "there is no basis for drawing the conclusion that crime rates are soaring in Sweden and that that is related to immigration".[101]

According to data gathered by Swedish police from October 2015 to January 2016, 5,000 police calls out of 537,466 involved asylum seekers and refugees.[114] According to Felipe Estrada, professor of criminology at Stockholm University, this shows how the media gives disproportionate attention to and exaggerates the alleged criminal involvement of asylum seekers and refugees.[114] Speaking in February 2017, Manne Gerell, a doctoral student in criminology at Malmo University, noted that while immigrants were disproportionately represented among crime suspects, many of the victims of immigrant crimes were other immigrants. He also opined that "Immigration will come with some cost, and we will likely have a bit more crime in a society with low crime rates".[115]

A Swedish Police report from May 2016 found that there have been 123 incidents of sexual molestation in the country's public baths and pools in 2015 (112 of them directed at girls). In 55% of cases, the perpetrator could be reasonably identified. From these identified perpetrators, 80% were of foreign origin.[116] The same report found 319 cases of sexual assault on public streets and parks in 2015. In these cases, only 17 suspected perpetrators have been identified, four of them Swedish nationals, with the remainder being of foreign origin. Another 17 were arrested, but not identified.[117] In 2015, when the highest number of asylum seekers entered the country, the number of reported rapes declined by 12%; it increased in 2016, and in 2017 had surpassed the 2014 level.[110]

According to Dagens Nyheter in 2017, at least 90% of all gun-related murders and attempted murders in Sweden are committed either by immigrants or those with at least one immigrant parent,[118] and according to Expressen, 94.5% of all members of career criminal gangs in Stockholm are either immigrants or have at least one immigrant parent.[119] The share of foreigners admitted to the Swedish Prison and Probation Service increased from 26% in 2003 to 33% in 2013, according to its statistics.[120] In its 2017 report on organized crime in Sweden, police stated that in most areas of Sweden with the highest crime rates (sv: särskilt utsatta områden), the population share of immigrants is around 50–60%.[121] In recent years, some of these areas have experienced riots, such as the 2008 Malmö mosque riots, 2010 Rinkeby riots, 2016 riots in Sweden and 2017 Rinkeby riots. Immigrants have also been associated with a series of highly publicised crimes, including the 2015 Ikea stabbing attack, 2016 Sweden asylum centre stabbing,[122] and the 2017 Stockholm attack.

A 2014 survey of several studies found that people with a foreign background are, on average, two times more likely to commit crimes than those born in Sweden. This figure has remained stable since the 1970s, despite the changes in numbers of immigrants and their country of origin.[123] Some studies reporting a link between immigration and crime have been criticised for not taking into account the population's age, employment and education level, all of which can affect the level of crime. In general, research that takes these factors into account does not support the idea that there is a link between immigration and crime.[124]

The last government report that collected statistics on immigration and crime was a 2005 study by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (Brå), and it found that people of foreign background were 2.5 times more likely to be suspected of crimes than people with a Swedish background. This included immigrants being four times more likely to be suspected of lethal violence and robbery, five times more likely to be investigated for sex crimes, and three times more likely to be investigated for violent assault.[125][126] The report was based on statistics for those "suspected" of offences. The Brå said that there was "little difference" in the statistics for those suspected of crimes and those actually convicted.[125] However, a 2006 government report suggested that immigrants face discrimination by law enforcement agencies, which could lead to meaningful differences between those suspected of crimes and those actually convicted.[127] A 2008 report by the Brå found evidence of discrimination towards individuals of foreign descent in the Swedish judicial system.[128] The 2005 report found that immigrants who entered Sweden during early childhood have lower crime rates than other immigrants.[129] By taking account of socioeconomic factors (gender, age, education and income), the crime rate gap between immigrants and natives decreases.[129] In 2017, some opposition parties called for a government report on the relationship between immigration and crime.[130]

A 2013 study by Stockholm University showed that the 2005 study's difference was due to the socioeconomic differences (e.g. family income, growing up in a poor neighborhood) between people born in Sweden and those born abroad.[131][98] The authors furthermore found "that culture is unlikely to be a strong cause of crime among immigrants".[98]

A study published in 1997 attempted to explain the higher than average crime rates among immigrants to Sweden. It found that between 20 and 25 percent of asylum seekers to Sweden had experienced physical torture, and many suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder. Other refugees had witnessed a close relative being killed.[132]

The 2005 study reported that persons from North Africa and the Middle East had the highest overrepresentation in crime statistics, whereas those born in Western Europe, South East Asia and the United States had the lowest representation.[125] However, a 1997 paper additionally found immigrants from Finland, South America, the Arab world and Eastern Europe to be overrepresented in crime statistics.[132] Studies have found that native-born Swedes with high levels of unemployment are also over-represented in crime statistics.[133]

A 2013 study found that both first- and second-generation immigrants have a higher rate of suspected offences than indigenous Swedes.[99] While first-generation immigrants have the highest offender rate, the offenders have the lowest average number of offenses, which indicates that there is a high rate of low-rate offending (many suspected offenders with only one single registered offense). The rate of chronic offending (offenders suspected of several offenses) is higher among indigenous Swedes than first-generation immigrants. Second-generation immigrants have higher rates of chronic offending than first-generation immigrants but lower total offender rates.[99]

In March 2018, the newspaper Expressen investigated gang rape court cases from the two preceding years and found that 43 men had been convicted. Their average age was 21, and 13 were under the age of 18 when the crime was committed. Of the convicted, 40 out of the 43 were either immigrants (born abroad) or born in Sweden to immigrant parents.[134]

Extremism

According to a 2017 study by the Swedish Defence University on Sweden's foreign fighters, a few people emigrated from Sweden to Afghanistan during the 1990s, mostly individuals with origins in the Horn of Africa and North Africa. At the start of the 2000s, individuals originating from the Middle East and North Africa comprised most of the persons involved in the Islamist milieu in Sweden. Additionally, male and female converts and Sweden-born second-generation immigrants were among the militant ranks. Some of the foreign fighters who emigrated from Sweden also originated in the former Yugoslavia and Russia.[135] As of 2017, most of the opposition fighters in Syria and Iraq were native Syrians and Iraqis. Foreign fighters in the region hailed from 38 different nations.[136] 80% of the individuals who arrived from Sweden were from the counties of Västra Götaland, Stockholm, Skåne and Örebro. Over 70% of the latter have been residents of designated vulnerable areas in Sweden. 75% of the foreign fighters arriving from Sweden were citizens of Sweden and 34% were Sweden-born.[137] Among the militant organizations that the foreign fighters in general belonged to were Hezbollah, Hamas, the PKK, the GIA, the Abu Nidal Organization, the Japanese Red Army, the Red Army Faction, Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, Al-Shabaab, Ansar al-Sunna and Ansar al-Islam. In 2010, the Swedish Security Service estimated that a total of 200 individuals were involved in the Swedish violent Islamist extremist milieu. According to the Swedish Defence University, most of these militants were affiliated with the Islamic State, with around 300 people traveling to Syria and Iraq to join the group and Al-Qaeda associated outfits like Jabhat al-nusra since 2012 (36 first-time travellers in 2012, 98 in 2013, 78 in 2014, 36 in 2015, and 5 in 2016).[138]

According to Göteborgs-Posten, 11% of the youths in the north-eastern suburbs of Gothenburg admit to being in favour of Islamic terrorism (with non-Muslims also included in the survey),[139] and 80% of female Muslim students admitted living under oppression from honour culture.[140]

According to research by the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency, the Muslim Brotherhood has a very strong foothold and influence in Sweden.[141]

Three times as many cases of terrorism financing were reported in Sweden in 2017, compared to 2016.[142]

Education

According to the National Agency for Education, in 2008, due to the closer similarity between the Swedish language and the native languages of Yugoslavia, pupils from the former Yugoslavia (who comprised a large portion of asylum immigrants during the 1990s) had greater ease in learning Swedish than pupils from more remotely located Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia and Syria.[144]

In 2015, about 35% of foreign-born residents had insufficient skills in literacy and numeracy, compared to about 5% of the domestic-born. The difference in skills was greater than in other comparable countries. The reasons for this discrepancy were that Sweden had a higher share of migration based on asylum rather than labour migration, and that many migrants had not resided in the country long enough to master the language.[145]

In 2018, researcher Pernilla Andersson Joona at Stockholm University found that 50% of recently arrived migrants had less than the Swedish 9-year basic education (Swedish: grundskolekompetens).[146]

In 2015, Radio Sweden reported that of immigrant children who come to Sweden at the age of 12 or older, only a quarter manage to finish high school and qualify for college. Of those who came to Sweden aged 9–11, about half passed their high school exams.[147]

Comparison between migrant and domestic education

| Low-educated in Sweden 2005–2016, ages 20–64, per region of birth [%] | |

| |

| Statistics Sweden[148] | |

In the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), qualifications from the country of origin could not be assumed to be equal to the same formal qualification from a Swedish institution; neither when it came to general skills in numeracy or literacy nor specific skills in a particular field. An analysis of PIAAC test scores found that migrants from the Arab states and Sub-Saharan Africa with a high education level (ISCED level 5 and 6) had numeracy skills equivalent to those of low education from Sweden, North America and Western Europe. Low education was defined as less than 2 years of secondary education, equivalent to the compulsory 9-year education (sv: grundskola).[149][150] Of the individuals who indicated that they had a high education level, 44% of those from the Arab states and 35% of those from Sub-Saharan Africa were assessed to have insufficient skills.[149]

Programme for International Student Assessment

In the 2015 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), a triennial worldwide study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) of 15-year-old native and immigrant pupils' scholastic performance, overall students in Sweden performed better than the OECD average in reading (stable since 2006), around the OECD average in mathematics (a decline since 2006), and close to the OECD average in science (a drop since 2006). Immigrants in Sweden generally underperformed compared to the OECD average and the gap in performance to native students showing a steadily widening trend since 2006.[151]

This underperformance of immigrants in Swedish schools has been cited as a significant part of the reason why Sweden has dropped more than any other European country in the international PISA rankings.[152][153][154][155]

Swedish For Immigrants

According to the SFI and Vuxenutbildningen Luleå, the Swedish For Immigrants adult language program comprises three different tiers: Sfi 1, Sfi 2, and Sfi 3. Sfi 1 consists of the study courses A and B, which are aimed at pupils with little or no education and individuals who are illiterate. Sfi 2 includes the study courses B and C, which are earmarked for students who have undergone many years of schooling but are unfamiliar with the Latin script. Sfi 3 includes the study courses C and D, which are geared toward pupils with college education that are seeking further studies.[156]

In the five years leading up to 2012, the number of illiterate migrants doubled, they had fewer than three years to no schooling from their origin country. In 2011, about 19,200 migrants in the Swedish for immigrants programme had 0–3 years of education. For instance in Borlänge, 4 out of 10 of those who completed the introduction for immigrants had no education at all, the majority being women.[157]

As of 2007, according to the National Center for SFI and Sweden as Another Speech (NC) and the Institute for Sweden as Another Speech (ISA), a total of 137 foreign languages were spoken as mother tongues by students within the Swedish For Immigrants program. Of these languages, the most common mother tongues of pupils within the Sfi 1 tier were Arabic (2,000), Thai (1,500), Somali (1,500), Kurdish/North Kurdish (1,150), Southern Kurdish (740) and Turkish (650).[158]

According to Statistics Sweden, as of 2012, the most common countries of birth for pupils in the Swedish For Immigrants program are Iraq (13,477), Somalia (10,355), Thailand (5,658), Poland (5,079), Iran (4,748), Turkey (3,344), China (3,408), Eritrea (3,618), Afghanistan (3,640), and Syria (3,257). The most common mother tongues spoken by the students are Arabic (18,886), Somali (10,525), Persian (7,162), Thai (5,707), Polish (5,100), English (4,796), Spanish (4,552), Tigrinya (3,623), Turkish (3,064), and North Kurdish (3,059).[159]

Espionage

Espionage where foreign nationals illegally spy on compatriot immigrants in Sweden has repeatedly happened in Sweden. According to Swedish Security Service, this is particularly the case for origin countries that do not respect human rights.[160] This is the case with Iran, Syria, Eritrea, Libya and Turkey. For instance Turkish interpreters in Sweden have encouraged migrants to become informants on behalf of Turkish authorities.[161]

Segregation

According to Statistics Sweden in 2007, the larger cities Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö are segregated. Segregation is not limited to the larger cities but also is a feature in many types of towns differing in size and location, like Kristianstad, Örebro, Trollhättan, Borås, Eskilstuna, Helsingborg, Örnsköldsvik and Jönköping. Children with Nordic or EU25 heritage more often grow up in areas dominated by Swedes, while children from Africa, Asia and non-EU countries grow up in areas high immigrant population.[162]

According to researcher Emma Neuman at Linnaeus University, segregation sets in at population share around 3-4% of non-European migrants in a district, while European immigration shows no such trend. The study comprised the 12 largest municipalities of Sweden for the period 1990–2007. High income earners and highly educated move out of non-European migrant districts first where ethnic segregation in turn leads to social segregation.[163]

A study at Örebro University concluded that while Swedish parents stated positive views towards the values of multiculturalism, in practice they still chose Swedish-majority schools for their offspring so their children won't be an ethnic minority during their formative years and to get a good environment to develop their native Swedish language.[163]

Public health

| Number of HIV healthcare patients in Sweden ages 0–85 male & female | |

| |

| Source: National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden[164] | |

According to the Public Health Agency of Sweden, cases of tuberculosis have increased steadily among immigrants from about 200 in 1989 to a peak of 750 in 2015, in 2016 the number of cases dropped as fewer migrants arrived.[165] In the same period, the number of tuberculosis cases among Sweden-born dropped from 400 in 1989 to 50 in 2016.[165]

From 2006 to 2016, the number of individuals applying for treatment for HIV increased from 1,684 to 6,273 (373%), which according to National Board of Health and Welfare was due to increased immigration from countries with higher levels of HIV.[166]

According to the National Board of Health and Welfare in 2016, an estimated 20–30% of asylum seekers suffer from mental disorder.[167]

Based on UNICEF rates for the practice of female genital mutilation (FGM) in various countries in Africa, the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen) estimated in 2015 that around 38,000 foreign-born women living in Sweden may have been circumcised in their countries of origin. Socialstyrelsen indicated that there were no known instances of FGM procedures having been carried out while women resided in Sweden, and that although there may have been unreported cases, official figures for these were unavailable.[168]

Immigrants in Sweden of non-European background report three to four times as often as Swedish natives that they suffer from poor or very poor health. This is particularly evident in regard to diminished work abilities and physical disabilities, but also in regard to anxiety and nervousness. However, the disparities between Swedish born and non-Swedish born residents' health were in part explained by the social differences across groups. These include occupation, living accommodation, and to have poorer economic resources than the average citizen. This suggests that the social living conditions play significant role in the health of immigrants in Sweden.[Insert Medicine].[169] Furthermore, poorer health can also likely be contributed to the fact that a decade is typically necessary for a refugee[170] or immigrant to have the same living conditions of a native Swede. Finally, simply perceiving discrimination may also play a role in the high mental health illness rate among immigrants.[171]

Tuberculosis

Cases of tuberculosis (TB) in Sweden are connected to the patient's country of origin when that country has a high rate of TB. infectees born abroad constituted 34% of all cases in 1989 and the fraction of born abroad had increased to 82–89% in the 2008–2013 period.[172]

In 2009–2013, the largest group of TB were Somalis in Sweden, with around 1100 cases, with Eritreans in Sweden the next largest group with slightly below 200 cases. The next largest groups were from Afghanistan, Thailand, Ethiopia, Iraq, India and Pakistan.[172]

The TB infection rate of Somalis in Sweden (550 / 100 thousand) is higher than that of the rate in Somalia itself reported by WHO (290 / 100 thousand) likely due to the fact that Swedish health institutions are better at discovering an infection.[172]

In 2017, the average rate of infection in Sweden was 5.4 cases per 100 000 persons and years. The number of cases among patients born abroad was increasing and the number of patients born in Sweden was in steady decline since the 1940s.[173]

Trust

Sweden is together with other Nordic countries for its high level of both institutional and interpersonal trust.[174] According to surveys by SOM Institute, the trust in institutions were not affected by the large waves of immigration during the European migrant crisis.[175] A 2017 study by Lund University also found that social trust was lower among people in regions with high levels of past non-Nordic immigration than among people in regions with low levels of past immigration.[176] The negative effect on trust was more prononunced for immigration from culturally distant countries.[177]

Honour culture

In a 2018 interview, researcher Astrid Schlytter stated that polls had shown that a third of all girls with two foreign-born parents faced restrictions in school, are forbidden to have a boyfriend and must be a virgin when they marry and they are not allowed to choose whom they marry. Using patterns of behaviour observed in Denmark, Norway and the UK Schlytter estimated that 240 000 youth suffer under an honour culture (Swedish: hedersförtryck).[178]

Public opinion

A 2008 study which involved questionnaires to 5000 people, showed that less than a quarter of the respondents (23%) wanted to live in areas characterised by cultural, ethnic and social diversity.[180]

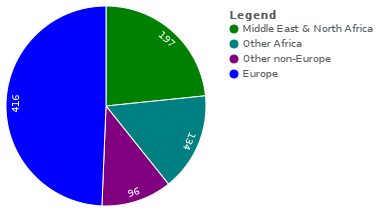

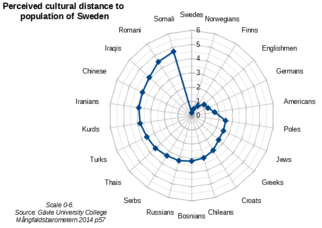

A 2014 study published by Gävle University College showed that 38% of the population never interacted with anyone from Africa and 20% never interacted with any non-Europeans.[181] The study concluded that while physical distance to the country of origin, also religion and other cultural expressions are significant for the perception of cultural familiarity. In general, peoples with Christianity as the dominant religion were perceived to be culturally closer than peoples from Islamic countries.[179]

A 2016 SOM Institute survey published by University of Gothenburg reported that between the years 2011 and 2016, the estimated share of people with concerns about the increasing number of immigrants increased from around 20% to 45%. In the period 2014–2016, the share of people having concerns about xenophobia increased from 38% to 45%,[182] and the proportion of individuals having concerns over an increased number of refugees rose to 29% in 2015.[183]

On the question of repatriation of the asylum immigrants, 61% of native respondents in 1990 thought that it was a good suggestion, with this figure steadily decreasing over the ensuing years to a low of around 40% in 2014. In 2015, there was an increase in respondents in favor of repatriation; 52% deemed it a good suggestion. The proportion of respondents who felt repatriation was neither a good nor bad proposal simultaneously dropped from almost 40% to 24%.[182]

In 2018, a poll by Pew Research found that a majority (52%) wanted fewer immigrants to be allowed into the country, 33% wanted to keep the current level and 14% wanted to increase immigration.[184]

Politics

Centerpartiet is a pro-immigration party, and in their campaign for the 2006 Swedish general election, they proposed to double the number of immigrants entering Sweden to 90,000 persons, or 1% of the Swedish population. This was to be facilitated by issuing green cards.[185]

In late 2012 the party stated it wanted to open the borders completely to immigration, including removing requirements for some degree of job skills and a clean criminal record. The party stressed the Canadian model and referred to it as a more successful one, stating that had Sweden followed it the population of Sweden would have been over 40 million in 2012.[186]

The former Social-Democratic Party minister of finance Kjell-Olof Feldt stated in October 2017 that the half million unemployed immigrants in Sweden are a ticking bomb.[187]

In December 2017 Minister for Finance Magdalena Andersson stated in an interview with Dagens Nyheter that integration of immigrants had not worked well in Sweden since before 2015 and that the situation had become very strained since. Andersson added that the possibilities were greater in other European countries to receive housing and education where the asylum process is quicker. She also expressed that the Swedish Social Democratic Party should be self-critical about that Sweden cannot receive more migrants than society has the capacity to assimilate.[188]

Legal issues

See also

References

- "Sveriges befolkning från 1749 och fram till idag". Sverige i siffror (in Swedish). Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Tabeller över Sveriges befolkning 2009" [Tables on the population in Sweden 2009] (PDF) (in Swedish). Örebro: Statistiska centralbyrån. June 2010. pp. 20–27. ISSN 1654-4358.

- 6.5% of the EU population are foreigners and 9.4% are born abroad, Eurostat, Katya VASILEVA, 34/2011.

- "Preliminary Population Statistics, by month, 2014". SCB.se. 6 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- Befolkningsstatistik i sammandrag 1960–2017, February 2018 (note that this source says 14.7% instead of 14.3% for 2010)

- "Nya svenska medborgare från drygt 160 länder". Statistiska Centralbyrån (in Swedish). Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- Applications for asylum received, 2016 (available via Översikter och statistik från tidigare år)

- Gränskontroll och id-kontroll – vad är vad?

- "Sveriges framtida befolkning 2015–2060 – The future population of Sweden 2015–2060" (PDF). Statistics Sweden. p. 98. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- "Statistik – Migrationsverket". MigrationsVerket.se. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- "Migrationen kan fördubbla statens kostnader för pensionärer". 17 October 2017.

- "Pensionsmyndigheten svarar på regeringsuppdrag om migration". 13 October 2017.

- Haavio-Mannila, Elina (January 1983). "Level of Living of Immigrants in Sweden". International Migration. 21 (1): 15–38. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.1983.tb00075.x.

- Sanandaji, Tino (February 2017). "2 Ett invandringsland". Massutmaning [Mass Challenge] (in Swedish). Kuhzad Media. pp. 21–27. ISBN 978-91-983787-0-2.

- "Folkmängd efter födelseland" [Population by country of birth]. scb.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- The Swedish Integration Board (2006). Pocket Facts: Statistics on Integration. Integrationsverket, 2006. ISBN 91-89609-30-1. Available online in pdf format Archived 5 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 14 February 2007.

- Nilsson, Åke (2004). "Immigration and emigration in the postwar period" (PDF). www.scb.se (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Wickström, Mats (2015). The Multicultural Moment – The History of the Idea and Politics of Multiculturalism in Sweden in Comparative, Transnational and Biographical context, 1964–1975 (PDF). Åbo, Finland: Åbo Akademi University. pp. 7+8. ISBN 9789521231339. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2018.

- Larsson, Göran (2014). Islam och muslimer i Sverige – en kunskapsöversikt (PDF). Stockholm: Swedish Agency for Support to Faith Communities (SST). p. 41.

- Sweden: Restrictive Immigration Policy and Multiculturalism, Migration Policy Institute, 2006.

- Invandringens betydelse för skolresultaten. Stockholm: National Agency for Education (Sweden). 2016. p. 14. ISBN 978-91-7559-244-2.

Från år 2008 sker en markant förändring när det gäller vilken typ av länder de utlandsfödda eleverna invandrat från. Den ökande andelen utlandsfödda kommer i allt högre grad från utomeuropeiska länder med en låg utvecklingsnivå. Detta avspeglas också i de utlandsfödda elevernas föräldrars utbildningsnivå som har sjunkit de senaste fyra–fem åren. Rent språkligt är det generellt också svårare att lära sig svenska för elever från länder som Irak, Afghanistan, Somalia och Syrien jämfört med de mer närliggande områdena i före detta Jugoslavien varifrån en stor del av flyktinginvandringen skedde på 1990-talet.

- "Tabeller över Sveriges befolkning 2009 – Statistiska centralbyrån". SCB.se. 24 January 2009. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- https://www.migrationsverket.se/download/18.4100dc0b159d67dc614c03d/1498556488892/Beviljade%20uppeh%C3%A5llstillst%C3%A5nd%201980-2016.pdf (however, https://www.migrationsverket.se/download/18.4a5a58d51602d141cf4e84/1515067343329/Beviljade%20uppeh%C3%A5llstillst%C3%A5nd%202009-2017.pdf shows slightly different numbers)

- https://www.migrationsverket.se/download/18.4a5a58d51602d141cf41003/1515076326490/Asyls%C3%B6kande%20till%20Sverige%202000-2017.pdf

- Anja Eriksson/TT (3 January 2011). "Serber ökade flyktingströmmen". DN.SE. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "Malta has highest per capita rate of asylum applications". timesofmalta.com. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- Beviljade uppehållstillstånd och registrerade uppehållsrätter 2010. Migrationsverket.se

- "Varannan asylsökande från Syrien". Sydsvenskan (in Swedish). 1 January 2015.

- "Så många väntas söka asyl de närmaste åren". Expressen (in Swedish). 3 February 2015.

- "Färre söker asyl i Sverige". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). 28 April 2015.

- "Sweden surpasses refugee record set in 1992". Sveriges Radio. 12 October 2015.

- "Flyktingrekord sattes i helgen". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). 12 October 2015.

- Applications for asylum received, 2015 (available via Översikter och statistik från tidigare år)

- Higgins, Andrew (26 May 2013). "In Sweden, Riots Put an Identity in Question". New York Times. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- Traub, James (10 February 2016). "The Death of the Most Generous Nation on Earth". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- Beviljade uppehållstillstånd 2009–2017 (Granted residence permits 2009–2017, by the Swedish Migration Agency) (the percentage was calculated by adding the numbers in the relevant table)

- Side notes: For the 2000–2017 total of asylum seekers, 66% were men or boys, and 34% women or girls (Asylsökande till Sverige 2000–2017 – Asylum seekers to Sweden 2000–2017).

- During the record year 2015, 70.4% of the asylum seekers were men, and 29.6% were women ("Inkomna ansökningar om asyl, 2015" (PDF). 1 January 2016.).

- "Negativ rapportering om invandring dominerar | Journalisten". journalisten.se. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "Här är fakta: invandring vinklas oftast negativt". Skånska Dagbladet (in Swedish). 23 August 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- Sharp, Anette (1 March 2016). "Masked men attack 60 Minutes crew in Sweden". news.com.au. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- The Local (30 March 2016). "Norway's integration minister: We can't be like Sweden". The Local. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- Doyle, Alister (21 April 2016). "Child brides sometimes tolerated in Nordic asylum centers despite bans". Reuters (Oslo). Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ""Papperslösa" som håller sig undan utvisning har inte rätt till bidrag – dom från HFD". Dagens Juridik (in Swedish). Retrieved 10 November 2017. (the first instance was förvaltningsrätten, in Swedish)

- "Månadsstatistik – medicinska åldersbedömningar". 1 August 2017.

- "Myndighetsgemensam lägesbild om organiserad brottslighet 2018–2019 / Dnr:A495.196/2017" (PDF). Swedish Police Authority. pp. 8 & 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2018.

Under hösten 2015 skedde en stor ökning av antalet asylsökande till Sverige. Polismyndigheten bedömer att majoritetio av de asylsökande hade tagit sig till Sverige med hjälp av människosmugglare. Smugglingspaketen till Sverige bedöms kostar flera hundra tusen kronor per person.[...] Utnyttjande av personer i beroendeställningUnder hösten 2015 skedde en stor ökning av antalet asyl-sökande till Sverige. Asylsökande befinner sig ofta i en utsattsituation. De har bristande språkkunskaper och kännedomom hur det svenska samhället fungerar, vilket kan utnyttjas i brottsligt syfte. Polisen bedömer att majoriteten av de som söker asyl i Sverige bedöms ha tagit sig hit med hjälp av människosmugglare. Enligt polisen rör det sig i stort sett uteslutande om landsmän som smugglar landsmän. Många som har betalat för att ta sig till Sverige har betydande skulder till människosmugglarna och dessa skulder måste betalas av på något sätt

- "Myndighetsgemensam lägesbild om organiserad brottslighet 2018–2019 / Dnr:A495.196/2017" (PDF). Swedish Police Authority. p. 16.

Enligt uppgifter använder smugglingsnätverken de asylsökandes möjlighet att ordna egna boenden (EBO) i stället för boende anordnat av Migrationsverket. Genom sina kontakter i de särskilt utsatta områdena ordnar nätverken bostäder åt de personer som har smugglats. Det innebär att EBO kan innebära en utsatt situation för den asylsökande. Asylsökande kan till exempel utnyttjas som billig alternativt gratis arbetskraft och tvingas arbeta svart. En annan risk är 0,04 att de på pappret får en avtalsenlig lön men att de i praktiken får behålla en mycket låg andel av lönen och anordnaren tar 0,00 resten. Det finns även uppgifter om att asylsökande tvingas betala av skulden genom att lämna över ersättningarna de erhåller från välfärdssystemet till smugglarna.

- "Utländsk/svensk bakgrund" (in Swedish). Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- "Foreign citizens by country of citizenship, sex and year". Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "Adopted children and young persons, number by sex, age, country of birth and year". Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "Statistics Sweden".

- "Folkmängd efter födelseland 1900–2017". Statistics Sweden. 21 February 2018.

- "Folkmängd efter födelseland 1900–2017" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- Ritter, Karl (30 May 2016). "It's Raining Men! Sweden sees historic gender balance shift". Phys.org.

- Statistiska Centralbryan. 2015 https://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Statistik-efter-amne/Befolkning/Befolkningens-sammansattning/Befolkningsstatistik/25788/25795/Behallare-for-Press/399296/. Retrieved 3 May 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Swedish Population". World Population Review. May 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- The labour market for persons with a lower level of education 2005–2016 (ref AM 110 SM 1704) (PDF). Statistics Sweden. 21 November 2017. p. 40, Table21. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- "OECD Factbook 2015–2016 | OECD READ edition". OECD iLibrary. p. 25. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- The labour market for persons with a lower level of education 2005–2016 (ref AM 110 SM 1704) (PDF). Statistics Sweden. 21 November 2017. p. 47. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- "Lägre sysselsättning för personer med låg utbildningsnivå". Statistiska Centralbyrån (in Swedish). Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Sysselsättning i Sverige". Statistiska Centralbyrån (in Swedish). Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Bloomberg". Where Immigrants Get the Job Done, and Where they Don't. 25 May 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- "Seeking Asylum-and jobs". The Economist. 5 November 2016.

- "Finding the Way: A discussion of the Swedish Migrant Integration System" (PDF). OECD. July 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- "Fewer than 500 of 163,000 Aslyum Seekers found jobs". Thelocal.se. 31 May 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- "Working while you are an asylum seeker". Migrationsverket: Swedish Migration Agency. 26 March 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- Eklund, Johan; P. Larsson, Johan (April 2020). "När blir utrikesfödda självförsörjande?" (PDF) (in Swedish). Entreprenörskapsforum.

- "Invandringen är dyrare än det verkar". Kristianstadsbladet (in Swedish). 16 April 2020.

- "Alltför ljus bild av ekonomisk integration". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). 15 April 2020.

- "Integrationen går sämre än vi trott". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). 17 April 2020.

- "Integrationsproblemen har bara börjat". Hallandsposten (in Swedish). 17 April 2020.

- "Sverige behöver en plan för alla som inte kan försörja sig". Expressen (in Swedish). 16 April 2020.

- "Låg självförsörjning är hög risk". VT.se (in Swedish). 18 April 2020.

- "Den alltför långsamma integrationen". VT.se (in Swedish). 17 April 2020.

- "Redovisning av verksamheten". migrationsverket.se (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- Ekberg, Jan (August 1999). "Immigration and the public sector: Income effects for the native population in Sweden". Journal of Population Economics. 12 (3): 411–430. doi:10.1007/s001480050106. JSTOR 20007638.

- Ruist, Joakim (2015). "The Fiscal Cost of Refugee Immigration: The Example of Sweden". Population and Development Review. 41 (4): 567–581. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00085.x. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Aldén, Lina; Hammarstedt, Mats (2016). "Rapport till Finanspolitiska rådet 2016/Flyktinginvandring Sysselsättning, förvärvsinkomster och offentliga finanser" (PDF). finanspolitiskaradet.se (in Swedish). Finanspolitiska rådet. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- "Who bears the cost of integrating refugees?" (PDF). OECD Migration Policy Debates. 13 January 2017: 2.

- Konsekvensanalyser inför migrationspolitiska beslut / RIR 2017:25 (PDF). Riksrevisionen / Swedish National Audit Office. 2017. p. 13.

- "Kostnader för utbildning i svenska för invandrare år 2016". skolverket.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Samtliga verksamheter inom fritidshem och annan pedagogisk verksamhet, skola och vuxenutbildning – Kostnader – Riksnivå 2011. February 2017. p. near the bottom in .xls "Svenska för invandrare totalt" in thousands. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Samtliga verksamheter inom fritidshem och annan pedagogisk verksamhet, skola och vuxenutbildning – Kostnader – Riksnivå 2012. February 2017. p. near the bottom in .xls "Svenska för invandrare totalt" in thousands. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Samtliga verksamheter inom fritidshem och annan pedagogisk verksamhet, skola och vuxenutbildning – Kostnader – Riksnivå 2013. February 2017. p. near the bottom in .xls "Svenska för invandrare totalt" in thousands. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Samtliga verksamheter inom fritidshem och annan pedagogisk verksamhet, skola och vuxenutbildning – Kostnader – Riksnivå 2014. February 2017. p. near the bottom in .xls "Svenska för invandrare totalt" in thousands. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Samtliga verksamheter inom fritidshem och annan pedagogisk verksamhet, skola och vuxenutbildning – Kostnader – Riksnivå 2015. February 2017. p. near the bottom in .xls "Svenska för invandrare totalt" in thousands. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Samtliga verksamheter inom fritidshem och annan pedagogisk verksamhet, skola och vuxenutbildning – Kostnader – Riksnivå 2016. February 2017. p. near the bottom in .xls "Svenska för invandrare totalt" in thousands. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "SCB: Kostnader för kommunernas komvux, särvux och sfi, tkr efter uppgift och år". statistikdatabasen.scb.se. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Konsekvensanalyser inför migrationspolitiska beslut / RIR 2017:25 (PDF). Riksrevisionen / Swedish National Audit Office. 2017. p. 14.

- Konsekvensanalyser inför migrationspolitiska beslut / RIR 2017:25 (PDF). Riksrevisionen / Swedish National Audit Office. 2017. p. 10.

Under perioden ökade utgifterna inom statsbudgetens utgiftsområde (UO) 8 Migration kraftigt, samtidigt som samtliga långtidsprognoser över utgifter på området underskattade det verkliga budgetutfallet. Underskattningen har ökat med tiden och har under de senaste åren uppgått till åtskilliga miljarder kronor om året.

- Konsekvensanalyser inför migrationspolitiska beslut / RIR 2017:25 (PDF). Riksrevisionen / Swedish National Audit Office. 2017. p. 30.

- Konsekvensanalyser inför migrationspolitiska beslut / RIR 2017:25 (PDF). Riksrevisionen / Swedish National Audit Office. 2017. p. 43.

- "Ekonomiskt bistånd – årsstatistik 2016 – Belopp samt antal biståndsmottagare och antal biståndshushåll". 2015.

- Galte Schermer, Isabelle (2 November 2017). "Arbetslöshet – utrikes födda". www.ekonomifakta.se (in Swedish). Svenskt Näringsliv. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Johansson, David; Dernevik, Mats; Johansson, Peter (2010). "Långtidsdömda män och kvinnor i Sverige". www.kriminalvarden.se (in Swedish). kriminalvården. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

En majoritet (52,9%) av de långtidsdömda hade ett ursprung i annat land än Sverige.

- Westling Palm, Katrin (21 March 2016). "Asylinvandringensekonomiska effekter på pensionssystemet" (PDF). pensionsmyndigheten.se (in Swedish). Pensionsmyndigheten. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Ruist, Joakim. "Tid för integration–en ESO-rapport om flyktingars bakgrund och arbetsmarknadsetablering." Time for integration-an ESO-report on refugees' background and labour market participation]. Rapport till Expertgruppen för studier io ffentlig ekonomi 3 (2018).

- Sandelind, Clara. "Can the Welfare State Justify Restrictive Asylum Policies? A Critical Approach." Ethical Theory and Moral Practice (2019): 1-16.

- "A waxing crescent". The Economist. 27 January 2011.

- Hällsten, Martin; Szulkin, Ryszard; Sarnecki, Jerzy (1 May 2013). "Crime as a Price of Inequality? The Gap in Registered Crime between Childhood Immigrants, Children of Immigrants and Children of Native Swedes". British Journal of Criminology. 53 (3): 456–481. doi:10.1093/bjc/azt005. ISSN 0007-0955.

- Kardell, Johan; Martens, Peter L. (1 July 2013). "Are Children of Immigrants Born in Sweden More Law-Abiding Than Immigrants? A Reconsideration". Race and Justice. 3 (3): 167–189. doi:10.1177/2153368713486488. ISSN 2153-3687.

- "Why Swedish immigration is not out of control". The Independent. 1 March 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "Sweden – not perfect, but not Trump's immigrant-crime nightmare". Reuters. 21 February 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "Sweden to Trump: Immigrants aren't causing a crime wave". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "Facts on Sweden, immigration and crime". PolitiFact. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "Analysis | Trump asked people to 'look at what's happening … in Sweden.' Here's what's happening there". Washington Post. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "After Trump comments, the reality of crime and migrants in Sweden". France 24. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- Fahlén, Liv (6 February 2017). "Kriminologen: "Det här har vi vetat sedan 1974"" [Criminologist: We have known this since 1974]. SVT (in Swedish). Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- http://www.pdf-archive.com/2011/05/08/br-1996-2-invandrares-och-invandrares-barns-brottslighet-1/br-1996-2-invandrares-och-invandrares-barns-brottslighet-1.pdf p. 33, 42, 44 and 76 (standardized values judging by the comparison).

- "Tendensen i resultaten är att ju grövre brott desto större andel av de anmälda brotten har begåtts av invandrare." (page 33)

- When adjusted for sex, age and area of residence, the adjusted share of foreign-born individuals who at some occasion during the period were registered as having committed rape varied, between 0.2 per mille for individuals born in Bangladesh and Pakistan – which was the same rate as for individuals born in Sweden – up to 3.5 per mille for the category born in Algeria, Libya, Marocco and Tunisia (with 3.3 for individuals born in Italy) (unadjusted values for ALMT was 4.6). (Table 1.3; unadjusted values available in table 2.3)

- For children of immigrants, the adjusted over-representation for biltillgrepp (inklusive försök), robbery, and physical abuse towards unfamiliar woman was higher than for rape, ranging between 2.0 and 2.4. However, this chart says 4.0 for immigrants on physical abuse towards unfamiliar man, which seems inconsistent. Which value is correct?

- "KIT". kit.se.

- Nyheter, SVT (22 August 2018). "Ny kartläggning av våldtäktsdomar: 58 procent av de dömda födda utomlands". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Swedish Television/Uppdrag Granskning. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Sweden rape: Most convicted attackers foreign-born, says TV". BBC News. 22 August 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Lägesbild över sexuella ofredanden samt förslag till åtgärder (PDF). Swedish Police Authority / Nationella Operativa Avdelningen. May 2016. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2018.

- "Trump Exaggerates Swedish Crime - FactCheck.org". FactCheck.org. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "Sweden's rape crisis isn't what it seems". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "Ett fåtal brott i Sverige kopplas till flyktingar – DN.SE". DN.SE (in Swedish). 9 February 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- Baker, Peter; Chan, Sewell (20 February 2017). "From an Anchor's Lips to Trump's Ears to Sweden's Disbelief". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "Lägesbild över sexuella ofredanden samt förslag till åtgärder" (PDF) (in Swedish). Polisen. 16 May 2016. p. 15, section 3.8.1.5. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "Lägesbild över sexuella ofredanden samt förslag till åtgärder" (PDF) (in Swedish). Polisen. 16 May 2016. p. 11, section 3.8.1.2. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "Vanligt med utländsk bakgrund bland unga män som skjuter". 20 May 2017.

- "Brotten, skulderna, bakgrunden – sanningen om de gängkriminella i Stockholm". 30 June 2017.

- "Fler utländska fångar i svenska fängelser". Sveriges Radio. 23 August 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- Myndighetsgemensam lägesbild om organiserad brottslighet 2018–2019 / Dnr:A495.196/2017 (PDF). Stockholm: Nationella underrättelsecentret / Polismyndigheten. 2017. p. 20.

Diagram 15

External link in|publisher=(help) - Miller, Michael (3 February 2016). "'Horrible and tragic': Swedish asylum worker killed at refugee center". Washington Post. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- Amber Beckley, Johan Kardell and Jerzy Sarnecki. The Routledge Handbook on Crime and International Migration. Routledge. pp. 46–47.

- Amber Beckley, Johan Kardell and Jerzy Sarnecki. The Routledge Handbook on Crime and International Migration. Routledge. p. 42.

- "Brottslighet bland personer födda i Sverige och i utlandet – Brå". bra.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- "Immigrants behind 25% of Swedish crime". thelocal.se.