Immigration to Malta

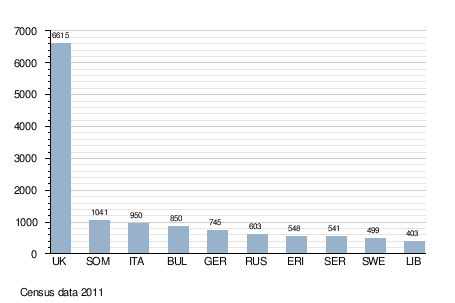

Immigration to Malta contributed to 4.9% of the total population of the Maltese islands in 2011, i.e. 20,289 persons of non-Maltese citizenship, of whom 643 were born in Malta. Most of migrants in Malta are EU citizens (12,215 or 60.2 per cent), predominantly from the United Kingdom (6,652 persons). The biggest community of non-EU nationals in Malta are the Somalis (1,049). In 2011, 2,279 non‐Maltese nationals were resident in institutional households, particularly in open centres and refugee homes.[1]

| Foreign population in Malta | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | % total | |||||||||||||||||

| 2005 | 12,112 | 3.0% | |||||||||||||||||

| 2011 | 20,289 | 4.9% | |||||||||||||||||

| 2019 | 98 918 | 21.0% | |||||||||||||||||

Demographically, non-Maltese residents in Malta are predominantly males (52.5 per cent) and younger than average (40.6 years of average age). They are mainly residing in the Northern Harbour District (38.3 per cent), consistently with the overall Maltese population (28.4 per cent residing in the district). A smaller proportion of non-Maltese citizens resides in the Southern Harbour District (7.6 per cent as opposed to 19.6 per cent for Maltese nationals).[1]

History of immigration to Malta

The current Maltese people, characterised by the use of the Maltese language and by Roman Catholicism, is the descendant - through much mixing and hybridation via different waves of immigration - of the Siculo-Arabic colonists who repopulated the Maltese islands in the beginning of the second millennium after a two-century lapse of depopulation that followed the Arab conquest by the Aghlabids in AD 870.[2][3] A genetic study by Capelli et al. indicates that Malta was barely inhabited at the turn of the tenth century and was likely to have been repopulated by settlers from Sicily and Calabria who spoke Siculo-Arabic, the progenitor of modern Maltese.[4][3] This is consistent with linguistic finding of no further sub-stratas beyond Arabic in the Maltese language, a very rare occurrence which may only be explained by a drastic lapse. Previous inhabitants of the islands - Phoenicians, Romans, Byzantines - did not leave any traces, as all nameplaces were lost and replaced. Modern historiography thus contest the traditional "Christian continuity thesis", positing instead a period of total depopulation of Malta at the end of the late antiquity.[5]

The Maltese islands remained largely Muslim-inhabited long after the end of Arab rule. The Arab administration was also kept in place[6] and Muslims were allowed to practise their religion freely until the 13th century.[7] As a result of this favourable environment, Muslims continued to demographically and economically dominate Malta for at least another 150 years after the Christian conquest.[8]

Between 1194 and 1530, the Kingdom of Sicily ruled the Maltese islands and a process of full latinisation started in Malta. The conquest of the Normans would lead to the gradual Romanization and Latinization of the Siculo-Arabic Muslim population of Malta, and the subsequent firm establishment of Roman Catholicism.[9][10] Until 1224, however, there remained a strong Muslim segment of society. By the end of the 15th century all Maltese Muslims would be forced to convert to Christianity and had to find ways to disguise their previous identities by Latinizing or adopting new surnames.[11]

After the Norman conquest, the population of the Maltese islands kept growing mainly through immigration from the north (Sicily and Italy), with the exile to Malta of the entire male population of the town of Celano (Italy) in 1223 (though most of them returned home few years later), the stationing of a Norman (Swabian) and Sicilian garrison on Malta in 1240, the arrival of several thousands Aragonese soldiers in 1283 to 1425, and the settlement in Malta of noble families from Sicily and the Crown of Aragon between 1372 and 1450. As a consequence of this, Capelli et al. found in 2005 that "the contemporary males of Malta most likely originated from Southern Italy, including Sicily and up to Calabria."[12]

Malta was then ruled by the Order of Saint John as a vassal state of the Kingdom of Sicily from 1530 to 1798. For the next 275 years, these famous "Knights of Malta" made the island their domain and made the Italian language official. The members of the Order came from the various noble families of Europe, thus providing Malta with a steady influx of affluent immigrants. Together with the Knights, in 1530, 400 (or up to several thousands according to other sources) Rhodian sailors, soldiers and slaves moved to Malta, possibly bringing along the few Byzantine words in Maltese language. Further immigration of several thousand Greek-rite Christians from Sicily in 1551 and again in 1566 may also have helped.

The XIX and first half of the XX century were for Malta marked by membership in the British Empire. Its excellent harbours became a prized asset for the British, especially after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. The island became a military and naval fortress, the headquarters of the British Mediterranean fleet, with some 22,000 British servicemen posted in Malta from 1807 to 1979,[13] as well as other British and Irish that settled in Malta over the decades. The islands also saw a steady influx of labourers from the other parts of the Empire, such as Indian textile traders from Sindh (see: Indians in Malta). In the same period, the learned class of Maltese society often identified with the Italians, particularly from the late XIX century Risorgimento period up to the second world war (see: Italian irredentism in Malta). Up to 891 Italian exiles also sought refuge in Malta in the late XIX century.

At the same time, overpopulation and poverty pushed the Maltese to emigrate well into the 1960s and 70s, particularly to other British colonies such as Australia, South Africa, Canada and Egypt, but also to Great Britain, Gibraltar, Corfu and the United States.

The late XX century saw the independence of Malta. Since this period, retired British servicemen and their families constitute the greatest part of foreign residents in Malta. Closer links to Qaddafi's Libya since the 1970s saw a growth of Libyans in Malta, while around 800 Ugandan Indians were resettled in Malta after they had been expelled by Idi Amin in 1972. In the early 1990s Malta was a first stop for refugees from Iraq and Kuwait during the first Gulf War, later often resettled to North America. Landing of Sub-Saharan asylum seekers grew from 2001 onwards, particularly of citizens of Somalia, Nigeria, Eritrea

Membership of the European Union in 2004 led to the growth of a community of Maltese in Belgium, while skilled workers from other EU (Italy, Bulgaria, Germany, Sweden) and non-EU countries (Serbia, Pakistan) moved to Malta to contribute to the growing industries, from construction to hotel services, banking and ICT. Malta's EU accession also prompted a renewed public discussion about Maltese identity and its role of bridge between Europe and the Mediterranean. As noted by Schembri in 2004, the Maltese tended to stress their belonging to Europe as a way of distinguishing themselves from North Africans, and the public debate on immigration has reflected entrenched xenophobic stereotypes. The public attitudes of the Maltese towards both North Africans and Sub-Saharan Africans - including refugees and asylum seekers - have worsened over time, paralleled by the government's strict detention policies for irregular migrants.[14]

Among the main immigrant communities in Malta:

- The Indian community in Malta (l-Indjani) was composed in 2007 of around 300 persons (45 families) stemming from the town of Hyderabad, Sindh (in today's Pakistan). They are Maltese citizens and reside in Malta since British times, originally as textile traders.[14]

- The Arab community counted around 3,000 persons in 2007, mostly originally from Libya and today Maltese citizens. The presence of the Libyans in Malta, with the only mosque of the island (Mariam Al-Batool Mosque in Paola, Malta), amounts to the good relations between the Qaddafi and Mintoff governments in the 1970s and 1980s.[14]

- The Albanians in Malta are a small community, originally arriving as refugees in 1999, when UNHCR resettled 110 persons from Kosovo to Malta.[14]

- Nigerians in Malta are one of the most visible communities of recent immigration, despite their relatively low number. Several of them are football players in the island's over 50 football clubs. (see Ndubisi Chukunyere and his daughter Destiny) [14]

Legislation

Immigration to Malta is mainly regulated by the Immigration Act and by the Asylum Act. The Immigration Act, passed in 1970, was reformed in the run-up to Malta's EU accession, in 2000 and 2002, in order to align it with the EU acquis. Maltese law maintains a rigid protectionist approach to labour migration. A Work Permit Scheme permits immigrants to reside and work in the country for a certain period of time, if their skills are absent locally or in short supply. Permits are issued by the Department for Citizenship and Expatriate Affairs. Applications are examined by a cross-governmental board in a process taking three to four months. Permits are usually yearly and can be renovated; applications for renewal should be submitted five months in advance. Foreign investors holding substantial shares in the manufacturing or financial services can apply for indefinite-time permits of stay. Work permits holders in Malta were 2,928 in 2003, of which 813 women. Most of them were issued to British citizens (387), then to "Yugoslavs"(306), Chinese (232), Indians (166), Bulgarians (146), Italians (143), Libyans (141).[14]

A Refugee Act was passed in Malta only in 2001, replacing the Catholic Church-based Emigrant Commission, which had till then partnered with UNHCR. The Refugee Act implement Malta's obligations under the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, establishing a Refugee Commission (REFCOM). In its first year of implementation, the Commission had to deal with 1,680 asylum seekers who reached Malta by boat in 2002. Persons who are recognised asylum or humanitarian protection are issued a residence permit and, upon request, a work permit.[14]

Non-Maltese residents in Malta

At the 2005 Census the non-Maltese population numbered 12,112 (3.0% of the total population). Of these, people with British (4,713), Italian (585), German (518) and Libyan (493) citizenship were most common.[15] Of the total population of 475,701 persons in 2019, 98,918, or 21.0%, are non-Maltese nationals.

Most of the foreign community in Malta, predominantly active or retired British nationals and their dependents, is centred on Sliema and surrounding modern suburbs. Other smaller foreign groups include Italians, French, and Lebanese, many of whom have assimilated into the Maltese nation over the decades.[16]

At the 2011 Census the non-Maltese population numbered 20,289. The citizenship of resident foreign nationals is shown below:[17]

The most common foreign places of birth for all residents at the time of the 2011 Census are shown below:

| Rank | Place of brth | Population (2011 census)[18] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10,480 | |

| 2 | 4,354 | |

| 3 | 1,766 | |

| 4 | 1,511 | |

| 5 | 1,246 | |

| 6 | 1,003 | |

| 7 | 951 | |

| 8 | 918 | |

| 9 | 875 | |

| 10 | 776 | |

| 11 | 656 | |

| 12 | 534 | |

| 13 | 507 | |

| 14 | 464 | |

| 15 | 454 | |

| 16 | 450 | |

| 17 | 417 | |

| 18 | 412 | |

| 19 | 347 | |

| 20 | 332 |

Visa policy

As an EU member state and a party to the Schengen Agreement, Malta applies the EU's visa policy. This means that to enter the country:

- Nationals of the EU and the European Economic Area (EEA) (Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein) and their special territories and of Switzerland require only a passport or a national identity card. Except for Croatian nationals, citizens of this category of countries do not require a permit to stay and work legally in Malta.[19]

- Nationals of a number of non-EU and non-EEA countries (most countries of the Western Balkans, most countries of the American continent, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, Malaysia and Japan) require only a passport and do not need a visa to reside in Malta for less than 90 days.

- Nationals of other countries need a passport and a visa to enter the country, visas being valid for one month.

Asylum seekers

Historically Malta gave refuge (and assisted in their resettlement) to eight hundred or so East African Asians who had been expelled from Uganda by Idi Amin and to just under a thousand Iraqis fleeing Saddam Hussein's regime. In 1990–1991, Malta hosted a number of Iraqi asylum-seekers, that were later resettled elsewhere, especially in North America.[20]

As from 2001, Malta has received a high number of landings of migrants from sub-Saharan Africa, many of whom were entitled to international protection. 2006 and 2007 saw about 1800 arriving each year.[21] Landings included 1173 people in 2009, 28 in 2010, 1577 in 2011, 2023 in 2012, and 741 up to mid July 2013.[22] Most of such persons were then resettled elsewhere in Europe or North America. Around 45% of immigrants landed in Malta have been granted refugee (5%) or protected humanitarian status (40%). A White Paper suggesting the grant of Maltese citizenship to refugees resident in Malta for over ten years was issued in 2005.

Between 2008 and 2012 Malta received, on average, the highest number of asylum seekers compared to its national population: 21.7 applicants per 1,000 inhabitants.[23] In 2011, most of these asylum applications were submitted by nationals of Somalia, Nigeria, Eritrea and Syria.[24] In 2012, more than half of the requests were by Somalian nationals alone.[25] During this period, Malta was criticized for its reception of asylum seekers, particularly those who were accommodated in open and closed reception centres (often referred to as "detention centers").[26]

As a member of the European Union and of the Schengen agreement, Malta is bound by the Dublin Regulation to process all claims for asylum by those asylum seekers that enter EU territory for the first time in Malta.[27]

Irregular migration

Since the late 20th century, Malta has become a transit country for migration routes from Africa towards Europe.[28] The estimated net inflow (using data for 2002 to 2004) was of 1,913 persons yearly. Over the last 10 years, Malta accepted back a yearly average of 425 returning emigrants.[29] During 2006, 1,800 irregular migrants reached Malta making the crossing from the North African coast. Most of them intended to reach mainland Europe and happened to come to Malta due to their sub-standard vessels breaking down or being caught by Maltese and other EU officials.[30][31] In the first half of 2006, 967 irregular immigrants arrived in Malta – almost double the 473 who arrived in the same period in 2005.[32] Many immigrants have perished in the journey across the Mediterranean, with one notable incident being the May 2007 Malta migrant boat disaster. Since that time, there have been several additional boat sinkings, and only as recently as April 2015, some 700 immigrants perished en route to Italy when their boat capsized.[33] During 2014 alone, approximately 3,500 migrants drowned in their attempt to reach Europe.

Very few migrants arrived in Malta in 2015, despite the fact that the rest Europe is experiencing a migrant crisis. Most migrants who were rescued between Libya and Malta were taken to Italy, and some refused to be brought to Malta.[34]

Malta has in the past considered adopting a push-back policy towards approaching migrants, pushing their boats back to Libya.[35] Such a policy, contrary to international law and the principle of non-refoulement, has been condemned by the European Court of Human Rights in a case against Italy, as it does not allow prospective asylum seekers to file their claims for international protection.[36]

Irregular migrants (formal Maltese: immigranti irregolari, informal: klandestini) who land in Malta are subject to a compulsory detention policy, being held in several camps organised by the Armed Forces of Malta (AFM), including those near Ħal Far and Ħal Safi. The compulsory detention policy has been denounced by several NGOs, and in July 2010, the European Court of Human Rights found that Malta's detention of migrants was arbitrary, lacking in adequate procedures to challenge detention, and in breach of its obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights.[37][38] Detention costs for the first half of 2006 cost €746,385.[39]

In 2005, Malta sought EU aid in relation to reception of irregular immigrants, repatriation of those denied refugee status, resettlement of refugees into EU countries and maritime security.[40] In December 2005, the European Council adopted The Global Approach to Migration: Priority Actions focusing on Africa and the Mediterranean; but the deployment of said actions has been limited to the western Mediterranean, thus putting further pressure on the Central Mediterranean route for irregular immigration of which Malta forms a part.

Investment-based citizenship scheme

In January 2014 Malta started granting citizenship for a €650,000 contribution plus investments, contingent on residence and criminal background requirements,[41] under the so-called "Individual Investor Programme"[42] Henley & Partners was originally appointed as sole agent for the sale of Maltese passport, but the Muscat government later opened the scheme to Maltese firms too. The procedure is managed formally by the governmental agency Identity Malta.[43]

The number and background of persons granted Maltese citizenship based on investment is unknown, as the Maltese government does not publish such data. Malta's Data Protection Commissioner confirmed that the publication of the number of passport buyers and their country of origin “may prejudice relations with a number of the countries of origin” and that revealing the agencies that handled their application “could reasonably be expected to prejudice commercial interests and, ultimately, the competitiveness of approved agents as it would reveal commercially-sensitive information”.[43]

The list of persons who were naturalised Maltese in the year 2015[44] includes over 900 names (listed by first name) without indication of previous/second citizenships and of reasons for naturalisation. This was criticised as not transparent enough.[45] Many of the names are typical Arab, Russian, and Chinese names. Most "investors" are understood to be interested in acquiring Maltese citizenship only as a tool to exploit EU citizenship rights and reside elsewhere in the Union, including the UK.[45] The European Parliament had objected to the programme as a sell-out of EU citizenship.[46]

The income from Malta's passport sale amounted to €163.5 million in 2016. Of this, 70% is deposited in the so-called National Development and Social Fund (NDSF), which was set up in July 2016. The use of the fund by the government is not regulated.[47]

Foreigners in Malta per locality, 2005 and 2011 censuses

Immigration to Malta grew significantly from 2005 to 2011, though remaining marginal overall (from 3% to 5% of the total population). The impact of immigration was also geographically diversified. Urban centres in the Northern Harbour where immigrant presence was already relevant saw a growth (2,095 residents in Sliema, from 10% to 15%; Gzira from 6 to 10%) while other areas quickly turned into immigrant residence areas (1,172 residents in St Julian's, from 1% to 14.5%). The Southern Harbour area was less affected, though immigrant population also grew, particularly in Paola (from 1% to 4.8%), Vittoriosa (from 1.5% to 3.3%), Valletta (from 1.8% to 3.1%), Marsa (from 1.5% to 3%), and Floriana (from 1.8% to 3%). In the South, Birżebbuġa saw non-Maltese population swell from 3% to 19% (1,986 residents). In the north, St Paul's Bay remains the area with the highest absolute number of non-Maltese resident (3,023, or 18.5%)

| 2005 | % | foreigners | % | 2011 | % | foreigners | % | |

| MALTA | 404,962 | 12,112 | 2,99% | 417,432 | 20,289 | 4.86% | ||

| Malta | 373,955 | 92.34% | 10,972 | 2.93% | 386,057 | 92.48% | 18,932 | 4.90% |

| Gozo and Comino | 31,007 | 7.66% | 1,140 | 3.68% | 31,375 | 7.52% | 1,357 | 4.33% |

| Southern Harbour | 81,047 | 20.01% | 827 | 1.02% | 79,438 | 19.03% | 1,542 | 1.94% |

| Cospicua | 5,657 | 1.40% | 67 | 1.18% | 5,249 | 1.26% | 91 | 1.73% |

| Fgura | 11,258 | 2.78% | 96 | 0.85% | 11,449 | 2.74% | 167 | 1.46% |

| Floriana | 2,240 | 0.55% | 40 | 1.79% | 2,014 | 0.48% | 62 | 3.08% |

| Ħal Luqa | 6,072 | 1.50% | 50 | 0.82% | 5,911 | 1.42% | 89 | 1.51% |

| Ħal Tarxien | 7,597 | 1.88% | 58 | 0.76% | 8,380 | 2.01% | 85 | 1.01% |

| Ħaż‐Żabbar | 14,671 | 3.62% | 77 | 0.52% | 14,916 | 3.57% | 101 | 0.68% |

| Kalkara | 2,882 | 0.71% | 20 | 0.69% | 2,946 | 0.71% | 51 | 1.73% |

| Marsa | 5,344 | 1.32% | 80 | 1.50% | 4,788 | 1.15% | 147 | 3.07% |

| Paola | 8,822 | 2.18% | 87 | 0.99% | 8,267 | 1.98% | 395 | 4.78% |

| Santa Luċija | 3,186 | 0.79% | 19 | 0.60% | 2,970 | 0.71% | 19 | 0.64% |

| Senglea | 3,074 | 0.76% | 55 | 1.79% | 2,740 | 0.66% | 52 | 1.90% |

| Valletta | 6,300 | 1.56% | 114 | 1.81% | 5,748 | 1.38% | 178 | 3.10% |

| Vittoriosa | 2,701 | 0.67% | 40 | 1.48% | 2,489 | 0.60% | 82 | 3.29% |

| Xgħajra | 1,243 | 0.31% | 24 | 1.93% | 1,571 | 0.38% | 23 | 1.46% |

| Northern Harbour | 119,332 | 29.47% | 4,996 | 4.19% | 120,449 | 28.85% | 7,768 | 6.45% |

| Birkirkara | 21,858 | 5.40% | 306 | 1.40% | 21,749 | 5.21% | 451 | 2.07% |

| Gżira | 7,090 | 1.75% | 404 | 5.70% | 7,055 | 1.69% | 756 | 10.72% |

| Ħal Qormi | 16,559 | 4.09% | 95 | 0.57% | 16,394 | 3.93% | 132 | 0.81% |

| Ħamrun | 9,541 | 2.36% | 109 | 1.14% | 9,043 | 2.17% | 184 | 2.03% |

| Msida | 7,629 | 1.88% | 401 | 5.26% | 7,748 | 1.86% | 737 | 9.51% |

| Pembroke | 2,935 | 0.72% | 52 | 1.77% | 3,488 | 0.84% | 142 | 4.07% |

| San Ġwann | 12,737 | 3.15% | 517 | 4.06% | 12,152 | 2.91% | 536 | 4.41% |

| Santa Venera | 6,075 | 1.50% | 735 | 12.10% | 6,789 | 1.63% | 142 | 2.09% |

| St Julian's | 7,752 | 1.91% | 71 | 0.92% | 8,067 | 1.93% | 1,172 | 14.53% |

| Swieqi | 8,208 | 2.03% | 702 | 8.55% | 8,755 | 2.10% | 995 | 11.36% |

| Ta' Xbiex | 1,860 | 0.46% | 116 | 6.24% | 1,556 | 0.37% | 113 | 7.26% |

| Tal‐Pietà | 3,846 | 0.95% | 150 | 3.90% | 4,032 | 0.97% | 313 | 7.76% |

| Tas‐Sliema | 13,242 | 3.27% | 1,338 | 10.10% | 13,621 | 3.26% | 2,095 | 15.38% |

| South Eastern | 59,371 | 14.66% | 1,042 | 1.76% | 64,276 | 15.40% | 3,130 | 4.87% |

| Birżebbuġa | 8,564 | 2.11% | 272 | 3.18% | 10,412 | 2.49% | 1,986 | 19.07% |

| Gudja | 2,923 | 0.72% | 19 | 0.65% | 2,994 | 0.72% | 24 | 0.80% |

| Ħal Għaxaq | 4,405 | 1.09% | 26 | 0.59% | 4,577 | 1.10% | 43 | 0.94% |

| Ħal Kirkop | 2,185 | 0.54% | 8 | 0.37% | 2,283 | 0.55% | 18 | 0.79% |

| Ħal Safi | 1,979 | 0.49% | 32 | 1.62% | 2,074 | 0.50% | 50 | 2.41% |

| Marsaskala | 9,346 | 2.31% | 445 | 4.76% | 11,059 | 2.65% | 672 | 6.08% |

| Marsaxlokk | 3,222 | 0.80% | 44 | 1.37% | 3,366 | 0.81% | 68 | 2.02% |

| Mqabba | 3,021 | 0.75% | 24 | 0.79% | 3,223 | 0.77% | 26 | 0.81% |

| Qrendi | 2,535 | 0.63% | 27 | 1.07% | 2,667 | 0.64% | 47 | 1.76% |

| Żejtun | 11,410 | 2.82% | 73 | 0.64% | 11,334 | 2.72% | 92 | 0.81% |

| Żurrieq | 9,781 | 2.42% | 72 | 0.74% | 10,287 | 2.46% | 104 | 1.01% |

| Western | 57,038 | 14.08% | 807 | 1.41% | 58,129 | 13.93% | 1,253 | 2.16% |

| Ħ'Attard | 10,405 | 2.57% | 157 | 1.51% | 10,553 | 2.53% | 217 | 2.06% |

| Ħad‐Dingli | 3,347 | 0.83% | 26 | 0.78% | 3,511 | 0.84% | 36 | 1.03% |

| Ħal Balzan | 3,869 | 0.96% | 94 | 2.43% | 4,101 | 0.98% | 286 | 6.97% |

| Ħal Lija | 2,797 | 0.69% | 69 | 2.47% | 2,977 | 0.71% | 105 | 3.53% |

| Ħaż‐Żebbuġ | 11,292 | 2.79% | 114 | 1.01% | 11,580 | 2.77% | 154 | 1.33% |

| Iklin | 3,220 | 0.80% | 43 | 1.34% | 3,169 | 0.76% | 63 | 1.99% |

| Mdina | 278 | 0.07% | 11 | 3.96% | 239 | 0.06% | 12 | 5.02% |

| Mtarfa | 2,426 | 0.60% | 30 | 1.24% | 2,585 | 0.62% | 28 | 1.08% |

| Rabat | 11,473 | 2.83% | 180 | 1.57% | 11,212 | 2.69% | 245 | 2.19% |

| Siġġiewi | 7,931 | 1.96% | 83 | 1.05% | 8,202 | 1.96% | 107 | 1.30% |

| Northern | 57,167 | 14.12% | 3,300 | 5.77% | 63,765 | 15.28% | 5,239 | 8.22% |

| Ħal Għargħur | 2,352 | 0.58% | 62 | 2.64% | 2,605 | 0.62% | 121 | 4.64% |

| Mellieħa | 7,676 | 1.90% | 621 | 8.09% | 8,661 | 2.07% | 946 | 10.92% |

| Mġarr | 3,014 | 0.74% | 50 | 1.66% | 3,479 | 0.83% | 97 | 2.79% |

| Mosta | 18,735 | 4.63% | 329 | 1.76% | 19,750 | 4.73% | 480 | 2.43% |

| Naxxar | 11,978 | 2.96% | 392 | 3.27% | 12,875 | 3.08% | 572 | 4.44% |

| St Paul's Bay | 13,412 | 3.31% | 1,846 | 13.76% | 16,395 | 3.93% | 3,023 | 18.44% |

| Gozo and Comino | 31,007 | 7.66% | 1,140 | 3.68% | 31,375 | 7.52% | 1,357 | 4.33% |

| Fontana | 850 | 0.21% | 16 | 1.88% | 882 | 0.21% | 14 | 1.59% |

| Għajnsielem | 2,570 | 0.63% | 93 | 3.62% | 2,645 | 0.63% | 112 | 4.23% |

| Għarb | 1,146 | 0.28% | 86 | 7.50% | 1,196 | 0.29% | 116 | 9.70% |

| Għasri | 418 | 0.10% | 30 | 7.18% | 431 | 0.10% | 40 | 9.28% |

| Munxar | 1,052 | 0.26% | 106 | 10.08% | 1,068 | 0.26% | 94 | 8.80% |

| Nadur | 4,192 | 1.04% | 126 | 3.01% | 3,973 | 0.95% | 112 | 2.82% |

| Qala | 1,616 | 0.40% | 78 | 4.83% | 1,811 | 0.43% | 130 | 7.18% |

| San Lawrenz | 598 | 0.15% | 28 | 4.68% | 610 | 0.15% | 39 | 6.39% |

| Ta' Kerċem | 1,665 | 0.41% | 50 | 3.00% | 1,718 | 0.41% | 65 | 3.78% |

| Ta' Sannat | 1,725 | 0.43% | 86 | 4.99% | 1,837 | 0.44% | 79 | 4.30% |

| Victoria | 6,395 | 1.58% | 102 | 1.59% | 6,252 | 1.50% | 163 | 2.61% |

| Xagħra | 3,934 | 0.97% | 193 | 4.91% | 3,968 | 0.95% | 212 | 5.34% |

| Xewkija | 3,111 | 0.77% | 30 | 0.96% | 3,143 | 0.75% | 56 | 1.78% |

| Żebbuġ | 1,735 | 0.43% | 116 | 6.69% | 1,841 | 0.44% | 125 | 6.79% |

Notable Maltese people of foreign descent

- Armenian-Maltese

- Mikhail Basmadjian (actor)

- Andy Eminyan (retired footballer)

- Australian-Maltese

- Kevin Moore

- Peter Pullicino

- Paul Fenech

- Mario Fenech

- British-Maltese

- Canadian-Maltese

- Danish-Maltese

- French-Maltese

- German-Maltese

- Greek-Maltese

- Irish-Maltese

- Italian-Maltese

- Giuseppe Calì

- Arnold Cassola

- Claudia Faniello

- Fabrizio Faniello

- Ugo Pasquale Mifsud

- Maria Adeodata Pisani

- Peter Pullicino

- Joseph Rizzo

- Davide Tucci

- Jewish-Maltese

- Moroccan-Maltese

- Nigerian-Maltese

- Palestinian-Maltese

- Serbian-Maltese

- Slovenian-Maltese

- Spanish-Maltese

- Swedish-Maltese

Notable foreign citizens living and working in Malta

- Albanians in Malta

- Argentinians in Malta

- Brasilians in Malta

- Fernando Lopes Alcântara

- Matheus Bissi

- Ronaille Calheira

- Douglas Cobo

- Gilmar da Silva

- Edison Luiz dos Santos

- Jorge Elias dos Santos

- Jorge Pereira da Silva

- Allan Kardeck

- Diogo Pinheiro

- Luís Rómulo de Castro

- Rômulo

- David da Silva

- Rodolfo Soares

- Márcio Teruel

- William da Silva Barbosa

- British in Malta

- Tanya Blake

- Anthony Burgess

- Chris de Burgh

- Tony Dyson

- Scott Fenwick

- Francis Jeffers

- Harry Luke

- Mark Miller (footballer)

- Montell Moore

- Brian Mundee

- Viv Nicholson

- Malcolm Robertson (footballer)

- Brian Talbot

- Carl Tremarco

- Cameroonians in Malta

- Abade Narcisse Fish

- Christian Pouga

- Colombians in Malta

- Congolese (D.R.C.) in Malta

- Czechoslovaks in Malta

- Dutch in Malta

- Germans in Malta

- Irish in Malta

- Italians in Malta

- Ivorians in Malta

- Lassana Cisse

- Japanese in Malta

- Lithuanians in Malta

- Nigerians in Malta

- Abubakar Bello-Osagie

- Olumuyiwa Aganun

- Murphy Akanji

- Benedict Akwuegbu

- Orosco Anonam

- Minabo Asechemie

- Ibrahim Babatunde

- Ndubisi Chukunyere

- Haruna Doda

- Alfred Effiong

- Augustine Eguavoen

- Udo Fortune

- Henry Isaac

- Godwin Mensha

- Chucks Nwoko

- Udo Nwoko

- Jojo Ogunnupe

- Stanley Ohawuchi

- Gabriel Okechukwu

- Digger Okonkwo

- Onome Sodje

- Akanni-Sunday Wasiu

- Godwin Zaki

- Poles in Malta

- Romanians in Malta

- Senegalese in Malta

- Serbians in Malta

- Srđan Dimitrov

- Dejan Đorđević

- Anđelko Đuričić

- Saša Jovanović

- Predrag Jović

- Milorad Kosanović

- Miloš Lepović

- Zoran Levnaić

- Jovica Milijić

- Nemanja Milovanović

- Neško Milovanović

- Boris Pašanski

- Stevan Račić

- Marko Rajić

- Milanko Rašković

- Nemanja Stošković

- Milan Vignjević

- Slovaks in Malta

- Trinidadians in Malta

- Ukrainians in Malta

See also

- Demographics of Malta

- Emigration from Malta

- List of countries by immigrant population

- List of sovereign states and dependent territories by fertility rate

References

- Census 2011 report

- "Gozo". IslandofGozo.org. 7 October 2007. Archived from the original on 22 August 2008.

- So who are the ‘real’ Maltese.

There’s a gap between 800 and 1200 where there is no record of civilisation. It doesn’t mean the place was completely uninhabited. There may have been a few people living here and there, but not much……..The Arab influence on the Maltese language is not a result of Arab rule in Malta, Prof. Felice said. The influence is probably indirect, since the Arabs raided the island and left no-one behind, except for a few people. There are no records of civilisation of any kind at the time. The kind of Arabic used in the Maltese language is most likely derived from the language spoken by those that repopulated the island from Sicily in the early second millennium; it is known as Siculo-Arab. The Maltese are mostly descendants of these people.

- Genetic Origin of Contemporary Maltese People.

Repopulation is likely to have occurred by a clan or clans (possibly of Arab or Arab-like speaking people) from neighbouring Sicily and Calabria. Possibly, they could have mixed with minute numbers of residual inhabitants, with a constant input of immigrants from neighbouring countries and later, even from afar. There seems to be little input from North Africa.

- Yosanne Vella, Wettinger has been vindicated, but why do historians still disagree?, Malta Today, 7 July 2015

- Krueger, Hilmar C. (1969). "Conflict in the Mediterranean before the First Crusade: B. The Italian Cities and the Arabs before 1095". In Baldwin, M. W. (ed.). A History of the Crusades, vol. I: The First Hundred Years. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 40–53.

- Arab Heritage in Malta | The Baheyeldin Dynasty

- Stefan Goodwin (1 Jan 2002). "2 (Islam and Realignments)". Malta, Mediterranean Bridge (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 31. ISBN 9780897898201.

Of greater cultural significance, the demographic and economic dominance of Muslims continued for at least another century and a half after which forced conversions undoubtedly permitted many former Muslims to remain.

- Kenneth M. Setton, "The Byzantine Background to the Italian Renaissance" in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 100:1 (Feb. 24, 1956), pp. 1–76.

- Daftary, Farhad. The Ismāʻı̄lı̄s: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37019-1.

- Stefan Goodwin (1 Jan 2002). "2 (Islam and Realignments)". Malta, Mediterranean Bridge (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 24. ISBN 9780897898201.

Though by the end of the fifteenth century all Maltese Muslims would be forced to convert to Christianity, they would still be in the process of acquiring surnames as required in European tradition. Ingeniously, they often used their father’s personal Arabic names as the basis of surnames, though there was a consistent cultural avoidance of extremely obvious Arabic and Muslim names, such as Muhammed and Razul. Also, many families disguised their Arabic names, such as Karwan (the city in Tunisia), which became Caruana, and some derived family names by translating from Arabic into a Roman form, such as Magro or Magri from Dejf.

- C. Capelli, N. Redhead, N. Novelletto, L. Terrenato, P. Malaspina, Z. Poulli, G. Lefranc, A. Megarbane, V. Delague, V. Romano, F. Cali, V.F. Pascali, M. Fellous, A.E. Felice, and D.B. Goldstein; "Population Structure in the Mediterranean Basin: A Y Chromosome Perspective," Archived 2013-08-28 at the Wayback Machine Annals of Human Genetics, 69, 1–20, 2005.

- Joseph M. Brincat, "Language and Demography in Malta: The Social Foundations of the Symbiosis between Semitic and Romance in Standard Maltese," in Malta: A Case Study in International Cross-Currents. Proceedings of the First International Colloquium on the history of the Central Mediterranean held at the University of Malta, 13–17 December 1989. Ed: S. Fiorini and V. Mallia-Milanes (Malta University Publications, Malta Historical Society, and Foundation for International Studies, University of Malta) at 91-110. Last visited 5 August 2007.

- Katia Amore, Malta, in Anna Triandafyllidou, Immigration: A Sourcebook, 2007

- "Census 2005" (PDF).

- Ltd, Allied Newspapers. "Genetic origin of contemporary Maltese".

- https://nso.gov.mt/en/publicatons/Publications_by_Unit/Documents/01_Methodology_and_Research/Census2011_FinalReport.pdf

- UNCHR Malta

- "EU Work permits and restrictions to labour market in EU countries-Your Europe". European Commission. October 2012.

- "Illegal immigration and Malta". 25 May 2009.

- TPPI Report, p.1

- "FRONTEXWatch - Malta". www.crimemalta.com.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "UNHCR - Document Not Found" (PDF).

- [Ibidem, p. 26]

- [Ibidem, p. 45]

- Cameron, Bobby Thomas (2010). "Asylum Policy and Housing for Asylum Seekers in the EU: A Look at Malta's Open Centres for Asylum Seekers". Perspectives on European Security: STETE Yearbook 2010. The Finnish Committee for European Security: STETE: 99–105.

- "Maltese Anger Mounts Over Rising Illegal Immigration". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- "Malta guards Europe's gates against African immigrants". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- National Statistics Office (2005). Demographic Review 2004. Valletta: National Statistics Office. p. 59. ISBN 99909-73-32-6. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006.

- "Frendo holds talks with three European Union Commission Members" (PDF) (Press release). Valletta: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 30 January 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- Sandford, Daniel (21 October 2005). "Immigrant frustration for Malta". BBC News Europe. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- "Statement by the Minister of Foreign Affairs Dr. Michael Frendo to resident EU Ambassadors on irregular immigration in Malta" (PDF) (Press release). Valletta: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 3 July 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- Mediterranean migrants: Hundreds feared dead after boat capsizes. BBC News (19 April 2015). Retrieved on 2017-05-01.

- "Rescued migrants refusing to be brought to Malta". Times of Malta. 26 September 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "Updated - Joseph Muscat rattles EU cage on pushbacks".

- Ltd, Allied Newspapers. "Italy violated human rights when it pushed migrants back to Libya - ECHR".

- "Malta: Migrant Detention Violates Rights". 18 July 2012.

- "Malta faces problems with children of illegal immigrants". Times of Malta. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- "Immigrants refused entry into Malta". The Sunday Times. UK. 16 July 2006. Retrieved 17 July 2006.

- Frendo, Michael (5 July 2005). "Illegal Immigration in Malta" (PDF). EU Foreign Ministers Council. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- Clenfield, Jason (11 March 2015). "Passport King Christian Kalin Helps Nations Sell Citizenship – Bloomberg Business". Bloomberg.com.

- Individual Investor Programme

- Times of Malta

- list of persons who were naturalised Maltese in the year 2015

- Politico Europe

- European Parliament

- Times of Malta, 6 November 2017