Maria Feodorovna (Dagmar of Denmark)

Maria Feodorovna (26 November 1847 – 13 October 1928), known before her marriage as Princess Dagmar of Denmark, was a Danish princess and Empress of Russia as spouse of Emperor Alexander III (reigned 1881–1894). She was the second daughter and fourth child of King Christian IX of Denmark and Louise of Hesse-Kassel; her siblings included Queen Alexandra of the United Kingdom, King Frederick VIII of Denmark and King George I of Greece. Her eldest son became the last Russian monarch, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia. She lived for ten years after he and his family were killed.

| Maria Feodorovna | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg) | |||||

| Empress consort of Russia | |||||

| Tenure | 13 March 1881 – 1 November 1894 | ||||

| Coronation | 27 May 1883 | ||||

| Born | Princess Dagmar of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg 26 November 1847 Yellow Palace, Copenhagen, Denmark | ||||

| Died | 13 October 1928 (aged 80) Hvidøre, Klampenborg, Denmark | ||||

| Burial |

| ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| House | Glücksburg | ||||

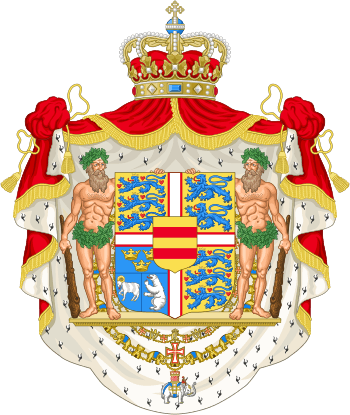

| Father | Christian IX of Denmark | ||||

| Mother | Louise of Hesse-Kassel | ||||

| Religion | Russian Orthodox prev. Lutheranism | ||||

Early life

Princess Marie Sophie Frederikke Dagmar was born at the Yellow Palace in Copenhagen. Her father was Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, a member of a relatively impoverished princely cadet line. Her mother was Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel.

She was baptised as a Lutheran and named after her kinswoman Marie Sophie of Hesse-Kassel, Queen Dowager of Denmark as well as the medieval Danish queen, Dagmar of Bohemia. Her godmother was Queen Caroline Amalie of Denmark. Growing up, she was known by the name Dagmar. Most of her life, she was known as Maria Feodorovna, the name which she took when she converted to Orthodoxy immediately before her 1866 marriage to the future Emperor Alexander III. She was known within her family as "Minnie".

In 1852 Dagmar's father became heir-presumptive to the throne of Denmark, largely due to the succession rights of his wife Louise as niece of King Christian VIII. In 1853, he was given the title Prince of Denmark and he and his family were given an official summer residence, Bernstorff Palace. Dagmar's father became King of Denmark in 1863 upon the death of King Frederick VII.

Due to the brilliant marital alliances of his children, he became known as the "Father-in-law of Europe." Dagmar's eldest brother would succeed his father as King Frederick VIII of Denmark (one of whose sons would be elected as King of Norway). Her elder, and favourite, sister, Alexandra married Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII) in March 1863. Alexandra, along with being queen consort of King Edward VII, was also mother of George V of the United Kingdom, which helps to explain the striking resemblance between their sons Nicholas II and George V. Within months of Alexandra's marriage, Dagmar's second older brother, Wilhelm, was elected as King George I of the Hellenes. Her younger sister was Thyra, Duchess of Cumberland. She also had another younger brother, Valdemar.

During her upbringing, Dagmar, together with her sister Alexandra, was given swimming lessons by the Swedish pioneer of swimming for women, Nancy Edberg;[1] she would later welcome Edberg to Russia, where she came on royal scholarship to hold swimming lessons for women.

Engagements and marriage

The rise of Slavophile ideology in the Russian Empire led Alexander II of Russia to search for a bride for the heir apparent, Tsarevich Nicholas Alexandrovich, in countries other than the German states that had traditionally provided consorts for the tsars. In 1864, Nicholas, or "Nixa" as he was known in his family, went to Denmark where he was betrothed to Dagmar. On 22 April 1865 he died from meningitis. His last wish was that Dagmar would marry his younger brother, the future Alexander III. Dagmar was distraught after her young fiancé's death. She was so heartbroken when she returned to her homeland that her relatives were seriously worried about her health. She had already become emotionally attached to Russia and often thought of the huge, remote country that was to have been her home. The disaster had brought her very close to "Nixa's" parents, and she received a letter from Alexander II in which the Emperor attempted to console her. He told Dagmar in very affectionate terms that he hoped she would still consider herself a member of their family.[2] In June 1866, while on a visit to Copenhagen, the Tsarevich Alexander asked Dagmar for her hand. They had been in her room looking over photographs together.[3]

Dagmar left Copenhagen on 1 September 1866. Hans Christian Andersen, who had occasionally been invited to tell stories to Dagmar and her siblings when they were children, was among the crowd which flocked to the quay in order to see her off. The writer remarked in his diary, "Yesterday, at the quay, while passing me by, she stopped and took me by the hand. My eyes were full of tears. What a poor child! Oh Lord, be kind and merciful to her! They say that there is a brilliant court in Saint Petersburg and the tsar's family is nice; still, she heads for an unfamiliar country, where people are different and religion is different and where she will have none of her former acquaintances by her side."

Dagmar was warmly welcomed in Kronstadt by Grand Duke Constantine Nikolaevich of Russia and escorted to St. Petersburg, where she was greeted by her future mother-in-law and sister-in-law on 24 September. On the 29th, she made her formal entry in to the Russian capital dressed in a Russian national costume in blue and gold and traveled with the Empress to the Winter Palace where she was introduced to the Russian public on a balcony. Catherine Radziwill described the occasion: ”rarely has a foreign princess been greeted with such enthusiasm… from the moment she set foot on Russian soil, succeeded in winning to herself all hearts. Her smile, the delightful way she had of bowing to the crowds…, laid immediately the foundation of …popularity” [4]

She converted to Orthodoxy and became Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna of Russia. The lavish wedding took place on 9 November [O.S. 28 October] 1866 in the Imperial Chapel of the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg. Financial constraints had prevented her parents from attending the wedding, and in their stead, they sent her brother, Crown Prince Frederick. Her brother-in-law, the Prince of Wales, had also travelled to Saint Petersburg for the ceremony; pregnancy had prevented the Princess of Wales from attending.[5] After the wedding night, Alexander wrote in his diary, "I took off my slippers and my silver embroidered robe and felt the body of my beloved next to mine... How I felt then, I do not wish to describe here. Afterwards we talked for a long time."[6] After the many wedding parties were over the newlyweds moved into the Anichkov Palace in Saint Petersburg where they were to live for the next 15 years, when they were not taking extended holidays at their summer villa Livadia in the Crimean Peninsula.

Tsesarevna

Maria Feodorovna was beautiful and well received by her Russian peers. Early on she made it a priority to learn the Russian language and to try to understand the Russian people. She rarely interfered with politics, preferring to devote her time and energies to her family, charities, and the more social side of her position. She had also seen the student protests of Kiev and St. Petersburg in the 1860s, and when police were beating students, the students cheered on Maria Feodorovna, to which she replied "They were quite loyal, they cheered me. Why do you allow the police to treat them so brutally?"[7] Her one exception to official politics was her militant anti-German sentiment due to the annexation of Danish territories by Prussia in 1864, a sentiment also expressed by her sister, Alexandra. Prince Gorchakov remarked about this policy: “it is our belief, that Germany will not forget that both in Russia and in England [sic] a Danish Princess has her foot on the steps of the throne.”[4] Maria Feodorovna suffered a miscarriage in 1866 in Denmark while horseback riding.

On 18 May 1868, Maria Feodorovna gave birth to her eldest son, Nicholas. Her next son, Alexander Alexandrovich, born in 1869, died from meningitis in infancy. She would bear Alexander four more children who reached adulthood: George (b. 1871), Xenia (b. 1875), Michael (b. 1878), and Olga (b. 1882). As a mother, she doted on and was quite possessive of her sons. She had a more distant relationship with her daughters.

In 1873, Maria, Alexander, and their two eldest sons made a journey to the United Kingdom. The imperial couple and their children were entertained at Marlborough House by the Prince and Princess of Wales. The royal sisters Maria and Alexandra delighted London society by dressing alike at social gatherings.[8] The following year, Maria and Alexander welcomed the Prince and Princess of Wales to St. Petersburg; they had come for the wedding of the Prince's younger brother, Alfred, to Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna, daughter of Tsar Alexander II and the sister of the tsarevich.[9]

Empress of Russia

On the morning of 13 March 1881, her father-in-law Alexander II of Russia, aged 62, was killed by a bomb on the way back to the Winter Palace from a military parade. In her diary, Maria later described how the wounded, still living Emperor was taken to the palace: "His legs were crushed terribly and ripped open to the knee; a bleeding mass, with half a boot on the right foot, and only the sole of the foot remaining on the left."[10] Alexander II died a few hours later. Although the people were not enamoured of the new emperor, they adored Russia's new empress. As Maria's contemporaries said of her: "She is truly an empress." She was not altogether pleased with her new status. In her diary she wrote, "Our happiest and serenest times are now over. My peace and calm are gone, for now I will only ever be able to worry about Sasha."[11] Despite being haunted by her father-in-law's gruesome death and her anxiety over the safety of her husband, at Alexander II's funeral, she was at least afforded the comfort of the presence of her brother-in-law and favourite sister, the Prince and Princess of Wales, the latter of whom, despite her husband's reluctance and Queen Victoria's objections, stayed on in Russia with Maria for several weeks after the funeral.

Alexander and Maria were crowned at the Assumption Cathedral in the Kremlin in Moscow on 27 May 1883. Just before the coronation, a major conspiracy had been uncovered, which cast a pall over the celebration. Nevertheless, over 8000 guests attended the splendid ceremony. Because of the many threats against Maria and Alexander III, the head of the security police, General Cherevin, shortly after the coronation urged the Tsar and his family to relocate to Gatchina Palace, a more secure location 50 kilometres outside St. Petersburg. The huge palace had 900 rooms and was built by Catherine the Great. The Romanovs heeded the advice. Maria and Alexander III lived at Gatchina for 13 years, and it was here that their five surviving children grew up. Under heavy guard, Alexander III and Maria made periodic trips from Gatchina to the capital to take part in official events.

Maria is described as a success in her social role as Empress, loved to dance at the balls of high society and became a popular socialite and hostess of the Imperial balls; her daughter Olga commented, “Court life had to run in splendor, and there my mother played her part without a single false step.”,[4] and a contemporary remarked on her success: “of the long gallery of Tsarinas who have sat in state in the Kremlin or paced in the Winter Palace, Marie Feodorovna was perhaps the most brilliant”.[4] She longed for the balls and gatherings in the Winter Palace. These also occurred at Gatchina. Alexander used to enjoy joining in with the musicians, although he would end up sending them off one by one. When that happened, Maria knew the party was over.[12]

As tsarevna, and then as tsarina, Maria Feodorovna had something of a social rivalry with the popular Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna, wife of her Russian brother-in-law, Grand Duke Vladimir. This rivalry had echoed the one shared by their husbands, and served to exacerbate the rift within the family.[13] While Maria Feodorovna knew better than to publicly criticise both the Grand Duke and Duchess in public,[13] Marie Pavlovna had earned the caustic epithet of "Empress Vladimir" from the tsarina.[14]

Nearly each summer, Maria, Alexander and their children would make an annual trip to Denmark, where her parents, King Christian IX and Queen Louise, hosted family reunions. Maria's brother, King George I, and his wife, Queen Olga, would come up from Athens with their children, and the Princess of Wales, often without her husband, would come with some of her children from the United Kingdom. In contrast to the tight security observed in Russia, the tsar, tsarina and their children relished the relative freedom that they could enjoy at Bernstorff and Fredensborg. The annual family meetings of monarchs in Denmark was regarded as suspicious in Europe, where many assumed they secretly discussed state affairs. Bismarck nicknamed Fredensborg “Europe’s Whispering Gallery”[4] and accused Queen Louise of plotting against him with her children. Maria also had a good relationship with the majority of her in-laws, and was often asked to act as a mediator between them and the tsar. In the words of her daughter Olga: “She proved herself extremely tactful with her in-laws, which was no easy task”.[4]

During Alexander III's reign, the monarchy's opponents quickly disappeared underground. A group of students had been planning to assassinate Alexander III on the sixth anniversary of his father's death at the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg. The plotters had stuffed hollowed-out books with dynamite, which they intended to throw at the Tsar when he arrived at the cathedral. However, the Russian secret police uncovered the plot before it could be carried out. Five students were hanged in 1887; amongst them was Aleksandr Ulyanov, older brother of Vladimir Lenin.

The biggest threat to the lives of the tsar and his family, however, came not from terrorists, but from a derailment of the imperial train in the fall of 1888. Maria and her family had been at lunch in the dining car when the train jumped the tracks and slid down an embankment, causing the roof of the dining car to nearly cave in on them.

When Maria's eldest sister Alexandra visited Gatchina in July 1894, she was surprised to see how weak her brother-in-law Alexander III had become. At the time Maria had long known that he was ill and did not have long left. She now turned her attention to her eldest son, the future Nicholas II, for it was on him that both her personal future and the future of the dynasty now depended.

Nicholas had long had his heart set on marrying Princess Alix of Hesse-Darmstadt, a favourite grandchild of Queen Victoria. Despite the fact that she was their godchild, neither Alexander III nor Maria approved of the match. Nicholas summed up the situation as follows: "I wish to move in one direction, and it is clear that Mama wishes me to move in another – my dream is to one day marry Alix."[15] Maria and Alexander found Alix shy and somewhat peculiar. They were also concerned that the young Princess was not possessed of the right character to be Empress of Russia. Nicholas's parents had known Alix as a child and formed the impression that she was hysterical and unbalanced, which may have been due to the loss of her mother and youngest sister, Marie, to diphtheria when she was just six.[15] It was only when Alexander III's health was beginning to fail that they reluctantly gave permission for Nicholas to propose.

Empress Dowager

On 1 November 1894, Alexander III died aged just 49 at Livadia. In her diary Maria wrote, "I am utterly heartbroken and despondent, but when I saw the blissful smile and the peace in his face that came after, it gave me strength."[16] Two days later, the Prince and Princess of Wales arrived at Livadia from London. While the Prince of Wales took it upon himself to involve himself in the preparations for the funeral, the Princess of Wales spent her time comforting grieving Maria, including praying with her and sleeping at her bedside.[17] Maria Feodorovna's birthday was a week after the funeral, and as it was a day in which court mourning could be somewhat relaxed, Nicholas used the day to marry Alix of Hesse-Darmstadt, who took the name Alexandra Feodorovna.[18]

Once the death of Alexander III had receded, Maria again took a brighter view of the future. "Everything will be all right", as she said. Maria continued to live in the Anichkov Palace in St. Petersburg and at Gatchina Palace. In May 1896, she travelled to Moscow for the coronation of Nicholas and Alexandra.

As a new Imperial Train was constructed for Nicholas II in time for his coronation, Alexander III's "Temporary Imperial Train" (composed of the cars that had survived the Borki disaster and a few converted standard passenger cars) was transferred to the Empress Dowager's personal use.[19]

During the first years of her son's reign, Maria often acted as the political adviser to the Tsar. Uncertain of his own ability and aware of her connections and knowledge, Tsar Nicholas II often told the ministers that he would ask her advice before making decisions, and the ministers sometimes suggested this themselves. It was reportedly on her advice that Nicholas initially kept his father's ministers.[4] Maria herself estimated that her son was of a weak character and that it was better that he was influenced by her than someone worse. Her daughter Olga remarked upon her influence: “she had never before taken the least interest … now she felt it was her duty. Her personality was magnetic and her zest of activity was incredible. She had her finger on every educational pulse in the empire. She would work her secretaries to shreds, but she did not spare herself. Even when bored in committee she never looked bored. Her manner and, above all, her tact conquered everybody”.[4] After the death of her spouse, Maria came to be convinced that Russia needed reforms to avoid a revolution.[4] According to courtier Paul Benckendorff there was a scene when Maria asked her son not to appoint the conservative Wahl as minister for internal affairs: “during which one [the empress dowager] almost threw herself at his [the tsar's] knees' begging him not to make this appointment and to choose someone who could make concessions. She said that if Nicholas did not agree, she would 'leave for Denmark, and then without me here let them twist your head around'".[4] Nicholas did appoint her favored candidate, and she reportedly told her favoured candidate the liberal reformist Peter Sviatopolk-Mirsky to accept by saying: “You must fulfil my son’s wish; If you do, I will give you a kiss”.[4] After the birth of a son to the tsar the same year, however, Nicholas II replaced his mother as his political confidant and adviser with his wife, Empress Alexandra.[4]

Maria Feodorovna's grandson-in-law, Prince Felix Yusupov, noted that she had great influence in the Romanov family. Sergei Witte praised her tact and diplomatic skill. Nevertheless, despite her social tact, she did not get along well with her daughter-in-law, Tsarina Alexandra, holding her responsible for many of the woes that beset her son Nicholas and the Russian Empire in general. She was appalled with Alexandra's inability to win favour with public, and also that she did not give birth to an heir until almost ten years after her marriage, after bearing four daughters. The fact that Russian court custom dictated that an empress dowager took precedence over an empress consort, combined with the possessiveness that Maria had of her sons, and her jealousy of Empress Alexandra only served to exacerbate tensions between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law.[20] Sophie Buxhoeveden remarked of this conflict: “Without actually clashing they seemed fundamentally unable … to understand one another”, [4] and her daughter Olga commented: “they had tried to understand each other and failed. They were utterly different in character, habits and outlook”. [4] Maria was sociable and a good dancer, with an ability to ingratiate herself with people, while Alexandra, though more intelligent and beautiful, was very shy and closed herself off from the Russian people.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Maria was spending increasing time abroad. In 1906, following the death of their father, King Christian IX, she and her sister, Alexandra, who had become queen-consort of the United Kingdom in 1901, purchased the villa of Hvidøre. The following year, a change in political circumstances allowed Maria Feodorovna to be welcomed to England by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, Maria's first visit to England since 1873.[21] Following a visit in early 1908, Maria Feodorovna was present at her brother-in-law and sister's visit to Russia that summer. A little under two years later, Maria Feodorovna travelled to England yet again, this time for the funeral of her brother-in-law, King Edward VII, in May 1910. During her nearly three-month visit to England in 1910, Maria Feodorovna attempted, unsuccessfully, to get her sister, now Queen Dowager Alexandra, to claim a position of precedence over her daughter-in-law, Queen Mary.[22]

Empress Maria Feodorovna, the mistress of Langinkoski retreat, was also otherwise a known friend of Finland. During the first russification period, she tried to have her son halt the constraining of the grand principality's autonomy and to recall the unpopular Governor-General Bobrikov from Finland to some other position in Russia itself. During the second russification period, at the start of the First World War, the Empress Dowager, travelling by her special train through Finland to Saint Petersburg, expressed her continued disapprobation for the russification of Finland by having an orchestra of a welcoming committee play the March of the Pori Regiment and the Finnish national anthem "Maamme", which at the time were under the explicit ban from Franz Albert Seyn, the Governor-General of Finland.

In 1899, Maria's second son, George, died of tuberculosis in the Caucasus. During the funeral, she kept her composure, but at the end of the service, she ran from the church clutching her son's top hat that been atop the coffin and collapsed in her carriage sobbing.[23] Two years later, according to her daughter, Grand Duchess Olga, she arranged Olga's disastrous marriage to Peter, Duke of Oldenburg.[24] For years Nicholas refused to grant his unhappy sister a divorce, only relenting in 1916 in the midst of the War. When Olga attempted to contract a morganatic marriage with Nikolai Kulikovsky, Maria Feodorovna and the tsar tried to dissuade her, yet, they did not protest too vehemently.[25] Indeed, Maria Feodorovna was one of the few people who attended the wedding in November 1916.[25] In 1912, Maria faced trouble with her youngest son, when he secretly married his mistress, much to the outrage and scandal of both Maria Feodorovna and Nicholas.[26]

Maria Feodorovna disliked Rasputin, whom she regarded to be a dangerous charlatan, and when his activities damaged the reputation of the Tsar, she asked the Tsar and Empress to remove him from their vicinity. When the Tsar remained silent and Empress Alexandra answered and refused for both of them, Maria assumed the empress was the true regent and that she also lacked the capability for such a position: “My poor daughter-in-law does not perceive that she is ruining the dynasty and herself. She sincerely believes in the holiness of an adventurer, and we are powerless to ward off the misfortune, which is sure to come."[4] When the Tsar dismissed minister Vladimir Kokovtsov in February 1914 on the advice of Alexandra, Maria again reproached her son, who answered in such a way that she became even more convinced that Alexandra was the real ruler of Russia, and she called upon Kokovtsov and said to him: “My daughter-in-law does not like me; she thinks that I am jealous of her power. She does not perceive that my one aspiration is to see my son happy. Yet I see we are nearing some kind of catastrophe and the Tsar listens to no one but flatterers… Why do you not tell the Tsar everything that you think and know… if it is not already too late”.[4]

World War I

In May 1914 Maria Feodorovna travelled to England to visit her sister.[27] While she was in London, World War I broke out (July 1914), forcing her to hurry home to Russia. In Berlin the German authorities prevented her train from continuing toward the Russian border. Instead she had to return to Russia by way of (neutral) Denmark and Finland. Upon her return in August, she took up residence at Yelagin Palace, which was closer to St. Petersburg (renamed Petrograd in August 1914[28]) than Gatchina.[27] During the war she served as president of Russia's Red Cross.[29] As she had done a decade earlier in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, she also financed a sanitary train.[27]

During the war, there was great concern within the imperial house about the influence Empress Alexandra had upon state affairs through the Tsar, and the influence Grigori Rasputin was believed to have upon her, as it was considered to provoke the public and endanger the safety of the imperial throne and the survival of the monarchy.[30] On behalf of the imperial relatives of the Tsar, both the Empress's sister Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna and her cousin Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna had been selected to mediate and ask Empress Alexandra to banish Rasputin from court to protect her and the throne's reputation, but without success. In parallel, several of the Grand Dukes had tried to intervene with the Tsar, but with no more success.

During this conflict of 1916-1917, Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna reportedly planned a coup d'état to depose the Tsar with the help of four regiments of the imperial guard which were to invade the Alexander Palace, force the Tsar to abdicate and replace him with his underage son under the regency of her son Grand Duke Kirill.[31]

There are documents that support the fact that in this critical situation, Maria Feodorovna was involved in a planned coup d'état to depose her son from the throne in order to save the monarchy.[30] The plan was reportedly for Maria to make a final ultimatum to the Tsar to banish Rasputin unless he wished for her to leave the capital, which would be the signal to unleash the coup.[30] Exactly how she planned to replace her son is unconfirmed, but two versions are available: first, that Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia would take power in her name, and that she herself would thereafter become ruling empress; the other version further claims that Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich of Russia would replace the Tsar with his son, the heir to the throne, Maria's grandson Alexey, upon which Maria and Paul Alexandrovich would share power as regents during his minority.[30] Maria was asked to make her appeal to the Tsar after Empress Alexandra had asked the Tsar to dismiss minister Polianov. Initially, she refused to make the appeal, and her sister-in-law Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna stated to the French Ambassador: “It’s not want of courage or inclination that keeps her back. It's better that she don’t. She’s too outspoken and imperious. The moment she starts to lecture her son, her feelings run away with her; she sometimes says the exact opposite of what she should; she annoys and humiliates him. Then he stands on his dignity and reminds his mother he is the emperor. They leave each other in a rage.” [4] Eventually, she was however convinced to make the appeal. Reportedly, Empress Alexandra was informed about the planned coup, and when Maria Feodorovna made the ultimatum to the Tsar, the empress convinced him to order his mother to leave the capital.[30] Consequently, the Empress Dowager left Petrograd to live in the Mariyinsky Palace in Kiev the same year. She never again returned to Russia's capital. Empress Alexandra commented about her departure: “it’s much better Motherdear stays … at Kiev, where the climate is better and she can live as she wishes and hears less gossip”.[4]

In Kiev, Maria engaged in the Red Cross and hospital work,[32] and in September, the 50th anniversary of her arrival in Russia was celebrated with great festivities, during which she was visited by her son, Nicholas II, who came without his wife.[4] Empress Alexandra wrote to the Tsar: “When you see Motherdear, you must rather sharply tell her how pained you are, that she listens to slander and does not stop it, as it makes mischief and others would be delighted, I am sure, to put her against me…”[4] Maria did ask Nicholas II to remove both Rasputin and Alexandra from all political influence, but shortly after, Nicholas and Alexandra broke all contact with the Tsar's family.[4]

When Rasputin was murdered, part of the Imperial relatives asked Maria to return to the capital and use the moment to replace Alexandra as the Tsar's political adviser. Maria refused, but she did admit that Alexandra should be removed from influence over state affairs: “Alexandra Feodorovna must be banished. Don’t know how but it must be done. Otherwise she might go completely mad. Let her enter a convent or just disappear.”[4]

Revolution and exile

Revolution came to Russia in 1917, first with the February Revolution, then with Nicholas II's abdication on 15 March. After travelling from Kiev to meet with her deposed son, Nicholas II in Mogilev, Maria returned to the city, where she quickly realised how Kiev had changed and that her presence was no longer wanted. She was persuaded by her family there to travel to the Crimea by train with a group of other refugee Romanovs.

After a time living in one of the imperial residences in the Crimea, she received reports that her sons, her daughter-in-law and her grandchildren had been murdered. However, she publicly rejected the report as a rumour. On the day after the murder of the Tsar's family, Maria received a messenger from Nicky, "a touching man" who told of how difficult life was for her son's family in Yekaterinburg. "And nobody can help or liberate them - only God! My Lord save my poor, unlucky Nicky, help him in his hard ordeals!"[33] In her diary she comforted herself: "I am sure they all got out of Russia and now the Bolsheviks are trying to hide the truth."[34] She firmly held on to this conviction until her death. The truth was too painful for her to admit publicly. Her letters to her son and his family have since almost all been lost; but in one that survives, she wrote to Nicholas: "You know that my thoughts and prayers never leave you. I think of you day and night and sometimes feel so sick at heart that I believe I cannot bear it any longer. But God is merciful. He will give us strength for this terrible ordeal." Maria's daughter Olga Alexandrovna commented further on the matter, "Yet I am sure that deep in her heart my mother had steeled herself to accept the truth some years before her death."[35]

Despite the overthrow of the monarchy in 1917, the former Empress Dowager Maria at first refused to leave Russia. Only in 1919, at the urging of her sister, Queen Dowager Alexandra, did she begrudgingly depart, fleeing Crimea over the Black Sea to London. King George V sent the warship HMS Marlborough to retrieve his aunt. The party of 17 Romanovs included her daughter the Grand Duchess Xenia and five of Xenia's sons plus six dogs and a canary.[36][37]

After a brief stay in the British base in Malta, they travelled to England on the British ship the Lord Nelson, and she stayed with her sister, Alexandra. Although Queen Alexandra never treated her sister badly and they spent time together at Marlborough House in London and at Sandringham House in Norfolk, Maria, as a deposed empress dowager, felt that she was now "number two," in contrast to her sister, a popular queen dowager, and she eventually returned to her native Denmark. After living briefly with her nephew, King Christian X, in a wing of the Amalienborg Palace, she chose her holiday villa Hvidøre near Copenhagen as her new permanent home.

There were many Russian émigrées in Copenhagen who continued to regard her as the Empress and often asked her for help. The All-Russian Monarchical Assembly held in 1921 offered her the locum tenens of the Russian throne but she declined with the evasive answer "Nobody saw Nicky killed" and therefore there was a chance her son was still alive. She rendered financial support to Nikolai Sokolov, who studied the circumstances of the death of the Tsar's family, but they never met. The Grand Duchess Olga sent a telegram to Paris cancelling an appointment because it would have been too difficult for the old and sick woman to hear the terrible story of her son and his family.[38]

Death and burial

In November 1925, Maria's favourite sister, Queen Alexandra, died. That was the last loss that she could bear. "She was ready to meet her Creator," wrote her son-in-law, Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, about Maria's last years. On 13 October 1928 at Hvidøre near Copenhagen, in a house she had once shared with her sister Queen Alexandra, Maria died at the age of 80, having outlived four of her six children.[38] Following services in Copenhagen's Russian Orthodox Alexander Nevsky Church, the Empress was interred at Roskilde Cathedral.

In 2005, Queen Margrethe II of Denmark and President Vladimir Putin of Russia and their respective governments agreed that the Empress's remains should be returned to St. Petersburg in accordance with her wish to be interred next to her husband. A number of ceremonies took place from 23 to 28 September 2006. The funeral service, attended by high dignitaries, including the Crown Prince and Crown Princess of Denmark and Prince and Princess Michael of Kent, did not pass without some turbulence. The crowd around the coffin was so great that a young Danish diplomat fell into the grave before the coffin was interred.[39] On 26 September 2006, a statue of Maria Feodorovna was unveiled near her favourite Cottage Palace in Peterhof. Following a service at Saint Isaac's Cathedral, she was interred next to her husband Alexander III in the Peter and Paul Cathedral on 28 September 2006, 140 years after her first arrival in Russia and almost 78 years after her death.

Issue

Tsar Alexander III and Maria Feodorovna had four sons and two daughters:

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nicholas II of Russia | 18 May 1868 | 17 July 1918 | married 1894, Princess Alix of Hesse; had issue |

| Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich of Russia | 7 June 1869 | 2 May 1870 | died of meningitis at age 10 months and 26 days |

| Grand Duke George Alexandrovich of Russia | 9 May 1871 | 9 August 1899 | died of tuberculosis; had no issue |

| Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna of Russia | 6 April 1875 | 20 April 1960 | married 1894, Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich of Russia; had issue |

| Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich of Russia | 4 December 1878 | 13 June 1918 | married 1912, Natalia Brasova; had issue |

| Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia | 13 June 1882 | 24 November 1960 | married 1901, Duke Peter Alexandrovich of Oldenburg; no issue, 1916, Nikolai Kulikovsky; had issue |

Honours

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Paintings by Maria Feodorovna

Still-life. 1868

Still-life. 1868 Miser. 1890

Miser. 1890

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Maria Feodorovna (Dagmar of Denmark) |

|---|

References

- "Idun (1890): Nr 15 (121) (Swedish)" (PDF). Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- Korneva & Cheboksarova (2006), p. 55

- Lerche & Mandal (2003), pp. 171–172

- Hall, Coryne, Little Mother of Russia: A Biography of Empress Marie Feodorovna, ISBN 978-0-8419-1421-6

- Van der Kiste (2004), pp. 62, 63

- Lerche & Mandal (2003), p. 173

- Peter Kropotkin (1901). "The Present Crisis in Russia". The North American Review.

- Battiscombe (1969), pp. 127, 128

- Battiscombe (1969), p. 128

- Lerche & Mandal (2003), p. 175

- Lerche & Mandal (2003), p. 176

- Lerche & Mandal (2003), p. 179

- Van der Kiste (2004), p. 141

- King (2006), p. 63

- Lerche & Mandal (2003), p. 184

- Lerche & Mandal (2003), p. 185

- King (2006), p. 331

- King (2006), p. 344

- Malevinsky (1900)

- King (2006), p. 51

- Battiscombe (1969), p. 263

- Battiscombe (1969), p. 273

- King (2006), p. 57

- King (2006), p. 55

- King (2006), p. 56

- King (2006), p. 59

- "Empress Maria Fyodorovna". RusArtNet. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

-

Volkov, Solomon (2010). "5". St Petersburg: A Cultural History. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 337. ISBN 9781451603156. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

When St. Petersburg was renamed Petrograd in August 1914 by Nicholas II, it was intended to 'Slavicize' the capital of the empire at war with Germany.

- "Prominent Russians: Maria Feodorovna, Empress Consort of Russia". Russiapedia.rt.com. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- King, Greg, The Last Empress, Citadel Press Book, 1994. ISBN 0-8065-1761-1. p. 299-300

- King, Greg, The Last Empress, Citadel Press Book, 1994. ISBN 0-8065-1761-1. p. 319-26-300

- Isaeva, K. (2 October 2016). "Romanovs and charity: Helping the Russian army in the First World war". Russia Beyond the Headlines. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- The Diaries of Empress Marie Feodorovna, p. 239

- Lerche & Mandal (2003), p. 197

- Vorres (1985), p. 171

- Welch 2018, p. 246.

- Rappaport 2018, p. 269.

- Barkovets & Tenikhina (2006), p. 142

- Af mier, pmol. "Mand faldt ned i Dagmars grav" (in Danish). Nyhederne.tv2.dk. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- Bragança, Jose Vicente de; Estrela, Paulo Jorge (2017). "Troca de Decorações entre os Reis de Portugal e os Imperadores da Rússia" [Exchange of Decorations between the Kings of Portugal and the Emperors of Russia]. Pro Phalaris (in Portuguese). 16: 10–11. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "Real orden de Damas Nobles de la Reina Maria Luisa". Guía Oficial de España (in Spanish). 1928. p. 239. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

Bibliography

- Barkovets, A. I.; Tenikhina, V. M. (2006). Empress Maria Fiodorovna. St. Petersburg: Abris Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Battiscombe, Georgina (1969). Queen Alexandra. Constable & Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hall, Coryne (2001). Little Mother of Russia: a Biography of Empress Marie Feodorovna. London: Shepheard-Walwyn. ISBN 978-0-8419-1421-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- King, Greg (2006). The Court of the Last Tsar: Pomp, Power and Pageantry in the Reign of Nicholas II. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-72763-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Korneva, Galina; Cheboksarova, Tatiana (2006). Empress Maria Feodorovna's Favourite Residences in Russia and Denmark. St. Petersburg: Liki Rossi.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lerche, Anna; Mandal, Marcus (2003). A Royal Family – The Story of Christian IX and his European descendants. Aschehoug. ISBN 87-15-10957-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Malevinsky, P. (1900). Императорский ширококолейный поезд для путешествий по России постройки 1896 - 1897 гг. Составлено под руководством Временного Строительного Комитета по постройке Императорских поездов инженером П. Малевинским [Imperial broad-gauge train for travel in Russia, constructed in 1896-1897] (PDF) (in Russian). МПС России (Russia's Ministry of the Means of Transportation). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Rappaport, Helen (2018). The Race to save the Romanoffs. New York: St Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-1-250-15121-6.</ref>

- Van der Kiste, John (2004). The Romanovs: 1818–1959. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 075093459X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vorres, Ian (1985). The Last Grand Duchess. London: Finedawn Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Welch, Frances (2018). The Imperial Tea Party: Family, Politics and Betrayal; The Ill-fated British and Russian Royal Alliance. London: Short Books. ISBN 978-1-78072-306-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maria Fyodorovna (Dagmar of Denmark). |

- (in Russian, Danish, and English) Website of the Danish Cultural Society Dagmaria

- Newspaper clippings about Maria Feodorovna in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

Maria Feodorovna (Dagmar of Denmark) House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg Cadet branch of the House of Oldenburg Born: 26 November 1847 Died: 13 October 1928 | ||

| Russian royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vacant Title last held by Maria Alexandrovna (Marie of Hesse) |

Empress consort of Russia 1881–1894 |

Vacant Title next held by Alexandra Feodorovna (Alix of Hesse) |