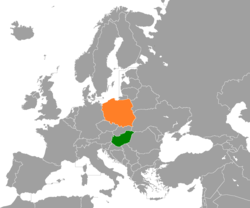

Hungary–Poland relations

Hungary–Poland relations are the foreign relations between Hungary and Poland. Relations between the two nations date back to the Middle Ages. The two Central European peoples have traditionally enjoyed a very close friendship, brotherhood and camaraderie rooted in a deep history of shared rulers, cultures, and faith. Both countries commemorate their fraternal relationship on March 23.

| |

Hungary |

Poland |

|---|---|

From 1370 to 1382 the Kingdom of Poland and Kingdom of Hungary entered into a personal union and were ruled by the same King, Louis the Great. This period in Polish history is sometimes known as the Andegawen Poland. Louis inherited the Polish throne from his maternal uncle Casimir III. After Louis's death the Polish nobles (the szlachta) decided to end the personal union, since they did not want to be governed from Hungary, and chose Louis's younger daughter Jadwiga as their new ruler, while Hungary was inherited by his elder daughter Mary. A second personal union with Poland was formed for the second time from 1440 to 1444.

Both countries are full members of NATO, joining it on the same day (March 12, 1999) and are also both members of the European Union as well as the Visegrád Four (along with Slovakia and the Czech Republic).

Polish and Hungarian high-ranking officials usually meet several times a week. The leaders of the two countries have been holding regular secret meetings to improve bilateral relations and work more closely together. Hungarian-Polish political scientist Dominik Hejj states: “The relations are very strong, and almost every week a Polish minister visits Hungary and vice versa”. One political expert said the two countries were putting the European Union on the spot by working towards their own power hub with Brussels “unable to do anything about it”.

Country comparison

| Hungary Hungary (Magyarország) |

Poland Republic of Poland (Rzeczpospolita Polska) | |

|---|---|---|

| Flag & Coat of arms |   |

|

| Population | 9,830,485 | 38,433,600 |

| Area | 93,028 km2 (35,919 sq mi) | 312,696 km2 (120,733 sq mi) |

| Population Density | 105.9/km2 (274.3/sq mi) | 123/km2 (318.6/sq mi) |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional republic | Unitary Semi-presidential constitutional republic |

| Capital | ||

| Largest City | ||

| Official language | Hungarian (de facto and de jure) | Polish (de facto and de jure) |

| First Leader | Grand Prince Árpád (895–907, traditionally) | Duke Mieszko I (960–992, traditionally) |

| Current Head of Government | Prime Minister Viktor Orbán (Fidesz; 1998–2002, 2010–present) | Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki (Law and Justice; 2017–present) |

| Current Head of State | President János Áder (Fidesz; 2012–present) | President Andrzej Duda (Law and Justice; 2015–present) |

| Main religions | 38.9% Catholicism (Roman, Greek), 13.8% Protestantism (Reformed, Evangelical), 0.2% Orthodox, 0.1% Jewish, 1.7% other, 16.7% Non-religious, 1.5% Atheism, 27.2% undeclared | 87.58% Roman Catholic, 7.10% Opting out of answer, 1.28% Other faiths, 2.41% Irreligious, 1.63% Not stated |

| Ethnic groups | 83.7% Hungarian, 3.1% Roma, 1.3% German, 14.7% not declared | 98% Poles, 2% other or undeclared |

| GDP (nominal) | $132.683 billion, $13,487 per capita | $614.190 billion, $16,179 per capita |

| External debt (nominal) | $32.600 billion (2012 Q4) – 80 % of GDP | $362.000 billion (2017 Q4) – 80 % of GDP |

| GDP (PPP) | $265.037 billion, $29,500 per capita[1] | $1.193 trillion, $29,500 per capita[2] |

| Currency | Hungarian forint (Ft) – HUF | Polish złoty (zł) – PLN |

| Human Development Index | 0.838 (very high) - 2017 | 0.865 (very high) - 2017 |

Historic relations

_01.jpg)

Good relations between Poland and Hungary date back to the Middle Ages. The Polish and Hungarian houses of nobility (such as the Piast dynasty or House of Árpád) often intermarried. Louis the Great was king of Hungary and Croatia from 1342 and king of Poland from 1370 until his death in 1382. He was his father’s heir, Charles I of the House of Anjou-Sicily (King of Hungary and Croatia) and his uncle’s heir, Casimir III the Great (king of Poland - last of the Piast dynasty). King Casimir had no legitimate sons. Apparently, in order to provide a clear line of succession and avoid dynastic uncertainty, he arranged for his nephew, King Louis I of Hungary, to be his successor in Poland. Louis' younger daughter Saint Jadwiga of Poland inherited the Polish throne, and became one of the most popular monarchs of Poland. In the 15th century, the two countries briefly shared the same king again, Poland's Władysław III of Varna, who perished, aged barely twenty, fighting the Turks at Varna, Bulgaria. In the 16th century, Poland elected the Hungarian nobleman Stephen Báthory as its king, who is regarded as one of Poland's greatest rulers.

Hungarian Revolution of 1848

In the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, a Polish general, Józef Bem, became a national hero of both Hungary and Poland. He was entrusted with the defence of Transylvania at the end of 1848, and in 1849, as General of the Székely troops.[3] On October 20, 1848 Józef Wysocki signed an agreement with the Hungarian government to form a Polish infantry battalion of about 1,200 soldiers. After agreement Wysocki organized in Hungary "Polish legion" of volunteers contained 2,090 foot soldiers and 400 Polish uhlans. They took part in the siege of the Arad fortress in the spring of 1849 and participated in all important battles at Szolnok, Hatvan, Tápió-Bicske and Isaszeg. After the Battle of Temesvár in August 1849, and the Hungarian capitulation at Világos, eight hundred of the remnants of the Legion escaped to Turkey.[4][5]

Polish–Soviet war

During the Polish–Soviet War (1919–21), after the Béla Kun government in Hungary was overthrown, Hungary offered to send 30,000 cavalry to Poland's aid, but the Czechoslovak government refused to allow them through the demilitarized zone that had existed between Czechoslovakia and Hungary since the end of the First World War. Nevertheless, Hungarian munitions trains did reach Poland.

In the beginning of July 1920, the Hungarian government of Prime Minister Pál Teleki made a decision to help Poland, delivering for free and at a critical moment of war at Hungary own expense through Romania's military supply: 48 million rounds to Mauser, 13 million rounds to Mannlicher, artillery ammunition, 30 thousands of Mauser rifles and several million spare parts, 440 field kitchens, 80 field ovens. On August 12, 1920, Skierniewice received transport, among others 22 million rounds to Mauser from the Manfréd Weiss factory in Csepel. It was the single most important foreign military contribution to Polish war effort.

From the Middle Ages well into the 20th century, Poland and Hungary had shared a historic common border. In the aftermath of World War I, the victorious allies had, at Versailles, transferred Upper Hungary as well as Carpathian Ruthenia, with its Slavic population, from defeated Hungary to Slavic-German-Hungarian nascent Czechoslovakia. Following the Munich Agreement (September 30, 1938) — which doomed Czechoslovakia to takeover by Germany — Poland and Hungary, from common as well as their own special interests, worked together, by diplomatic as well as paramilitary means, to restore their historic common border by engineering the return of Carpathian Rus to Hungary.[6] A step toward their goal was realized with the First Vienna Award (November 2, 1938).

Until mid-March 1939, Germany considered that, for military reasons, a common Hungarian-Polish frontier was undesirable. Indeed, when in March 1939 Hitler made an about-face and authorized Hungary to take over the rest of Carpatho-Rus (which was by then styling itself "Carpatho-Ukraine"), he warned Hungary not to touch the remainder of Slovakia, to whose territory Hungary also laid claim. Hitler meant to use Slovakia as a staging ground for his planned invasion of Poland. In March 1939, however, Hitler changed his mind about the common Hungarian-Polish frontier and decided to betray Germany's ally, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, who had already in 1938 begun organizing Ukrainian military units in a sich outside Uzhhorod, in Carpathian Ukraine, under German tutelage — a sich that Polish political and military authorities saw as an imminent danger to nearby southeastern Poland, with its largely Ukrainian population.[7][8] Hitler, however, was concerned that, if a Ukrainian army organized in Carpathian Rus were to accompany German forces invading the Soviet Union, Ukrainian nationalists would insist on the establishment of an independent Ukraine; Hitler, who had designs on Ukraine's natural and agricultural resources, did not want to deal with an independent Ukrainian government.[9]

World War II

Hitler would soon have cause to rue his decision regarding the fate of Carpatho-Ukraine. In six months, during his 1939 invasion of Poland, the common Polish-Hungarian border would become of major importance when Admiral Horthy's government, on the ground of long-standing Polish-Hungarian friendship, declined, as a matter of "Hungarian honor,"[10] Hitler's request to transit German forces across Carpathian Rus into southeastern Poland to speed that country's conquest. The Hungarian refusal allowed the Polish government and tens of thousands of military personnel to escape into neighboring Hungary and Romania, and from there to France and French-mandated Syria to carry on operations as the third-strongest Allied belligerent after Britain and France. Also, for a time Polish and British intelligence agents and couriers, including Krystyna Skarbek, used Hungary's Carpathorus as a route across the Carpathian Mountains to and from Poland.[11]

Revolution of 1956

A student demonstration in Budapest in support of the Polish October and asking for similar reforms in Hungary was one of the events that sparked the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.[12] During the revolution, Poles demonstrated their support for the Hungarians by donating blood for them; by 12 November 1956, 11,196 Poles had donated. The Polish Red Cross sent 44 tons of medical supplies to Hungary by air; even larger amounts were sent by road and rail.

Friendship Day

On March 12, 2007, Hungary's parliament declared March 23 the "Day of Hungarian-Polish Friendship", with 324 votes in favor, none opposed, and no abstentions. Four days later, the Polish parliament declared March 23 the "Day of Polish-Hungarian Friendship" by acclamation.[13]

2016 - Year of Hungarian-Polish solidarity

The Hungarian Parliament on the 29th of February, 2016 adopted a decree in a unanimous vote that declares 2016 a year of Hungarian-Polish solidarity. Under the decree state celebrations will be organised throughout the year to mark the 60th anniversary of the anti-communist uprising in Poland’s Poznan in June 1956 and Hungary’s anti-Soviet revolution four months later. The decree was submitted by the house speaker, the speaker of the Polish national minority in Hungary and the group leaders of the five parliamentary parties. A decree with the same content was adopted by the Polish Senate earlier in the month and by the Sejm on Friday last week. A Polish delegation led by Ryszard Terlecki participated.

Resident diplomatic missions

- Hungary has an embassy in Warsaw, a consulate-general in Kraków and a vice-consulate in Wrocław.[14]

- Poland has an embassy in Budapest.[15]

- Embassy of Hungary in Warsaw

Embassy of Poland in Budapest

Embassy of Poland in Budapest

See also

Notes

- https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2004rank.html

- https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2004rank.html

- Kálmán Deresnyi, General Bem's Winter Campaign in Transylvania, 1848-1849 (Hung.), (Budapest, 1896)

- Józef Wysocki, "Pamiętnik Jenerała Wysockiego, dowódcy Legionu Polskiego na Węgrzech z czasu kampanii węgierskiej w roku 1848 i 1849" digital version of Wysocki memoirs

- E. Kozłowski, Legion polski na Węgrzech 1848–1849, Warszawa 1983

- Józef Kasparek, "Poland's 1938 Covert Operations in Ruthenia", East European Quarterly", vol. XXIII, no. 3 (September 1989), pp. 366-67, 370. Józef Kasparek, Przepust karpacki: tajna akcja polskiego wywiadu (The Carpathian Bridge: a Covert Polish Intelligence Operation), p. 11.

- Józef Kasparek, "Poland's 1938 Covert Operations in Ruthenia", p. 366.

- On 17 September 1939, pursuant to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the Soviet Union entered and took control of eastern Poland, including southeastern Poland. That former southeastern part of Poland now comprises western Ukraine.

- Józef Kasparek, "Poland's 1938 Covert Operations in Ruthenia", pp. 370-71.

- Józef Kasparek, "Poland's 1938 Covert Operations in Ruthenia", p. 370.

- Józef Kasparek, "Poland's 1938 Covert Operations in Ruthenia," pp. 371–73;Józef Kasparek, Przepust karpacki (The Carpathian Bridge); and Edmund Charaszkiewicz, "Referat o działaniach dywersyjnych na Rusi Karpackiej" ("Report on Covert Operations in Carpathian Rus").

- "United Nations report of the Special Committee on the problem of Hungary", Page 145, para 441. Last accessed on 5 August 2012.

- Uchwała Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z dnia 16 marca 2007 r. (in Polish)

- Embassy of Hungary in Poland

- Embassy of Poland in Hungary

References

- Józef Kasparek, "Poland's 1938 Covert Operations in Ruthenia", East European Quarterly", vol. XXIII, no. 3 (September 1989), pp. 365–73.

- Józef Kasparek, Przepust karpacki: tajna akcja polskiego wywiadu (The Carpathian Bridge: a Covert Polish Intelligence Operation), Warszawa, Wydawnictwo Czasopism i Książek Technicznych SIGMA NOT, 1992, ISBN 83-85001-96-4.

- Edmund Charaszkiewicz, "Referat o działaniach dywersyjnych na Rusi Karpackiej" ("Report on Covert Operations in Carpathian Rus"), in Zbiór dokumentów ppłk. Edmunda Charaszkiewicza (Collection of Documents by Lt. Col. Edmund Charaszkiewicz), opracowanie, wstęp i przypisy (edited, with introduction and notes by) Andrzej Grzywacz, Marcin Kwiecień, Grzegorz Mazur, Kraków, Księgarnia Akademicka, 2000, ISBN 83-7188-449-4, pp. 106–30.