Poland–United States relations

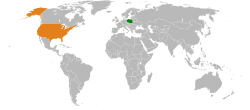

Polish–United States relations, alternatively known as the Polish–American relations, are the diplomatic, social, economic and cultural bilateral relations between Poland and the United States.

| |

Poland |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Polish Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, Warsaw |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Piotr Wilczek | Ambassador Georgette Mosbacher |

The official relations on a diplomatic level were initiated in 1919, after Poland established itself as a republic after 123 years of being under foreign rule following the Partitions of Poland. However, ties with the United States date back to the 17th century, when the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was one of Europe's largest great powers and many Poles immigrated to the Thirteen Colonies. During the American Revolutionary War, Polish military commanders Thaddeus Kościuszko and Casimir Pulaski contributed greatly to Patriot cause, with Kościuszko becoming a national hero in America. Since 1989, Polish–American relations have been strong and Poland is one of the chief European allies of the United States, being part of both NATO and the European Union. There is a strong cultural appreciation between the two nations (polonophilia). According to U.S. Department of State, Poland remains a "stalwart ally" and "one of strongest Continental partners in fostering security and prosperity, throughout Europe and the world".[1] Poland was also one of four participating countries in the U.S.-led Iraq War in 2003.

In addition to close historical ties, Poland is currently one of the most consistently pro-American nations in Europe and the world, with 79% of Poles viewing the U.S. favorably in 2002 and 67% in 2013.[2] According to the 2012 U.S. Global Leadership Report, 36% of Poles approve of U.S. leadership, with 30% disapproving and 34% uncertain,[3] and in a 2013 BBC World Service Poll, 55% of Poles view U.S. influence positively, the highest rating for any surveyed European country.[4]

Before the 20th century

Although the partitioning of Poland which erased the Polish state from the map in 1795 prevented the establishment of official diplomatic relations between Poland and the new American state, Poland, which enacted the world's second oldest constitution in 1791, always considered the United States a positive influence, and even in the 18th century, important Polish figures such as Kościuszko and Pulaski became closely involved with shaping US history. Haym Salomon, a Polish Jew, was the prime financier of the American side during the American Revolutionary War against Britain. Many Poles also emigrated to United States during the 19th century, forming a large Polish American community in urban centres such as Chicago.

American response to the November Uprising

Poland's November Uprising of 1831 and the fight for regaining independence from the neighbouring empires was extensively-documented and editorialized in American newspapers. As historian Jerzy Jan Lerski described, "one could reproduce in detail virtually the whole story of the November Uprising from the 1831 files of American dailies published at that time, regardless of the fact that they were usually four-sheet affairs with little space left for foreign news."[5] There was only a very small number of Poles in the United States at the time, but views of Poland were shaped positively by their support for the American Revolution. Several young men offered their military services to fight for Poland, the most well-known of which was Edgar Allan Poe who wrote a letter to his commanding officer March 10, 1831 to join the Polish Army should it be created in France.

Support for Poland was highest in the South, as Pulaski's death in Savannah, Georgia was well-remembered and memorialized. An American surgeon, Dr. Paul Fitzsimmons, from the State of Georgia, actually joined the Polish Army in 1831. He was in France at the time and, inspired by "how gallant Pulaski had fallen at the siege of Savannah during the Revolutionary struggle of 1776", he traveled to Warsaw as a field surgeon for the Polish infantry. The United States never initiated the creation of a military force for supporting Poland. Financial support and gifts were sent from the United States to the American-Polish Committee in France, which intended to purchase supplies and transport aid to Poland. American writer James Fenimore Cooper wrote an appeal for the organization at the height of his popularity, motivating a nationwide collection for Poland in American cities. French General Lafayette was an outspoken voice in France, urging for a French intervention to aid Poland in its independence from Russia. The French government sought to make peace with the Russian Empire and generally stayed out of the revolution.[6]

Following the collapse of the insurrection, American newspapers continued to publish news from British and French sources documenting oppression of Poles by Imperial Russia and also by the German Empire. Newspaper editors made mention of the Russians as "brutal" and "evil" whereas the Poles were "gallant" and "heroic" in their efforts. The American public was apprised of the ongoing suppression of the Polish Catholic Church and forced conscription of Poles into the Imperial Russian Army, hurting Russian-American relations. An American writer in Boston, Robin Carver, wrote a children's book in 1831 called Stories of Poland, which said that for Polish children, "Their houses are not peaceful and happy homes, but are open to the spies and soldiers of a cruel and revengeful government...There is no confidence, no repose, no hope for them, and will not be, till, by some more fortunate struggle, they shall drive the Russians from their borders, and become an independent people."[7] Poetic tributes to Poland were written in America, and literature denouncing Russian treatment towards Poland continued after the Uprising. The Russian Emperor, Nicholas I, and his emissaries asked the U.S. Secretary of State for a formal rebuke of American newspapers reporting the mistreatment of Poles. Then Secretary of State Edward Livingston chose to wait two months before responding to Russia's demands, but the United States Ambassador to Russia James Buchanan made promises to the Russians that the American press would circulate evidence that Russian cruelty was "much overplayed". Historian Jerzy Jan Lerski was critical of Buchanan's pro-Russian stance on the Polish issue, and said he made statements on Poland without visiting the country or "listening to Polish testimony".[8]

Lincoln and the Civil War

Poland's independence lost favor among American intellectuals during the American Civil War. Historians have argued that President Lincoln himself was sympathetic to the Poles but chose not to intervene in Europe's affairs out of fear that European powers would support the Confederacy. Historian Tom Delahaye pointed to 1863 as a critical breakdown in relations between the "Crimean Coalition" (Britain, France, and Austria) and Russia, with Poland's independence a key reason for conflict.[9] Russian sympathies were solidly in favor of the North, and Lincoln expressed non-interventionist policy towards Russia's "Polish problem". By doing so, he alienated himself from British and French politics and came closer to the Russians, contributing to a balance of power in favor of the tsar.

Second Polish Republic

After World War I, United States President Woodrow Wilson issued his principles for an end to the war, the Fourteen Points in which XIII point called for independent Poland with access to the sea - "An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant." On January 22, 1919, Secretary of State Robert Lansing notified Poland's Prime Minister and Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, that the United States recognized the Provisional Polish Government.

The United States established diplomatic relations with the newly formed Polish Republic in April 1919 but the relations between the two countries were distant, while positive (due to United States non-interventionism and Poland not being seen as important for U.S. interests).

Eventually both countries became part of the Allies in the Second World War, but there was relatively little need for detailed coordination between the United States and the Polish government in exile based in London.

Communist period

On July 5, 1945, the U.S. government recognized the communist government installed in Warsaw, thus abandoning the Polish Government in Exile. After 1950, Poland (or the Polish People's Republic since 1952) became a member of the Eastern Bloc, and as such, America's foe in the Cold War. The first U.S. ambassador to post-war Poland, Arthur Bliss Lane, wrote a book I Saw Poland Betrayed about how the Western Allies abandoned their former ally, Poland, to Soviet influence. Despite this, the Poles and the Polish government maintained very close and warm ties with the Western Bloc and the United States.

After Gomułka came to power in 1956, relations with the United States improved considerably. However, during the 1960s, reversion to a policy of full and unquestioning support for Soviet foreign policy objectives and negative attitude toward Israel during the Six-Day War caused those relations to stagnate. U.S.–Polish relations improved once more after Edward Gierek succeeded Gomułka. A consular agreement was signed under in 1972. In 1974, Gierek was the first Polish communist head of state to visit the United States. This action, among others, demonstrated that both sides wished to facilitate better relations.

The birth of Solidarity in 1980 raised the hope that progress would be made in Poland's external relations as well as in its domestic development. During this time, the United States provided $765 million in agricultural assistance and loans. Human rights and individual freedom issues, however, were not improved upon; the U.S. revoked Poland's most-favored-nation (MFN) status in response to the decision to ban on the Solidarity Movement in 1981 and instigation of martial law by the Polish United Workers' Party. MFN status was reinstated in 1987.

The Reagan administration engaged in clandestine support for Solidarity. CIA money was channeled through third parties.[10] CIA officers were barred from meeting Solidarity leaders, and the CIA's contacts with Solidarnosc activists were weaker than those of the AFL-CIO, which raised 300 thousand dollars from its members, which were used to provide material and cash directly to Solidarity. The U.S. Congress authorized the National Endowment for Democracy to promote democracy, and the NED allocated $10 million to Solidarity.[11] CIA support for Solidarity besides money included equipment and training,which was coordinated by Special Operations CIA division.[12] Henry Hyde, U.S. House intelligence committee member, stated that USA provided "supplies and technical assistance in terms of clandestine newspapers, broadcasting, propaganda, money, organizational help and advice".[13] Michael Reisman from Yale Law School named operations in Poland as one of the covert actions of CIA during Cold War.[14] Initial funds for covert actions by CIA were $2 million, but soon after authorization were increased and by 1985 CIA successfully infiltrated Poland.[15]

When the Polish government launched a crackdown of its own in December 1981, however, Solidarity was not alerted. Potential explanations for this vary; some believe that the CIA was caught off guard, while others suggest that American policy-makers viewed an internal crackdown as preferable to an "inevitable Soviet intervention."[16]

Third Polish Republic

The United States and Poland have enjoyed warm bilateral relations since 1989. Every post-1989 Polish government has been a strong supporter of continued American military and economic presence in Europe, and Poland is one of the most stable allies of the United States.

When Poland joined NATO on March 12, 1999 the two countries became part of the same military alliance. As well as supporting the Global War on Terror, Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan, and coalition efforts in Iraq (where Polish contingent was one of the largest), Poland cooperates closely with the United States on such issues as democratization, nuclear proliferation, human rights, regional cooperation in central and eastern Europe, and reform of the United Nations.

President Barack Obama visited Poland on 27–28 May 2011. He met with Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk and President Bronisław Komorowski. The American and Polish leaders discussed economic, military and technology cooperation issues.

In July 2017 US President Donald Trump in his second foreign travel visited Poland. He met with the President of Poland Andrzej Duda. President Trump and President Duda then held a joint press conference in the Royal Castle, Warsaw. President Trump thanked the Polish people and President Duda for the warm welcome he received in Warsaw.[17] He said: "Our strong alliance with Poland and NATO remains critical to deterring conflict and ensuring that war between great powers never again ravages Europe, and that the world will be a safer and better place. America is committed to maintaining peace and security in Central and Eastern Europe".[17]

President Trump also spoke with European leaders attending the Three Seas Initiative Summit in Warsaw."[17]

In 2018, Poland proposed that the United States open a permanent military base within its country. The Polish government would finance around $2 Billion of the cost of hosting American forces, if the proposal was accepted by the United States. Poland has proposed either Bydgoszcz, or Toruń, as potential base locations.[18] Since 1999, Poland has sought closer military ties with the United States.[19] In June 2019, both sides agreed to send 1,000 U.S. troops to Poland.[20] In September 2019, six locations were determined to host approximately 4,500 of the U.S. military in Poland, including: Poznań, Drawsko Pomorskie, Strachowice, Łask, Powidz and Lubliniec.[21]

Issues

Radosław Sikorski

Despite their apparently close relationship, Wprost (a Polish magazine) obtained a recording of Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski calling the Polish-US alliance "downright harmful" and caused a "false sense of security".,[22] while in a poll made in 2016, around 20% of questioned considered Americans a potential threat to Polish national security. Despite that, also in this poll, more than 50% of questioned considered Americans and Canadians as trustworthy.[23]

US missile defense complex in Poland

The US missile defense complex in Poland was part of the Ballistic Missile Defense European Capability of the US, to be placed in Redzikowo, Słupsk, Poland, forming a Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system in conjunction with a US narrow-beam midcourse tracking and discrimination radar system in the Brdy, Czech Republic. The plan was cancelled in 2009.

Polish society was divided on the issue. According to a poll by SMG/KRC released by TVP 50 per cent of respondents rejected the deployment of the shield on Polish soil, while 36 per cent supported it.[24]

In October 2009, with a trip by Vice President Joe Biden to Warsaw, a new, smaller interceptor project on roughly the same schedule as the Bush administration plan, was introduced, and welcomed by Prime Minister Donald Tusk.[25]

Visa Waiver Program

A substantial and repeated criticism in Poland of the United States' past approach to Poland revolves about United States' refusal to allow Poles a short-stay visa-free entry, despite the fact that most European Union countries – often much less supportive of US on the international scene – have no visa requirements. However, President Donald Trump announced as of November 11, 2019, Poles may now travel to the United States visa-free with stays up to 90 days. [26]

During his visit to Poland in 2011, Pres. Obama said of the Visa Waiver Program, "I am going to make this a priority. And I want to solve this issue before very long. My expectation is that this problem will be solved during my presidency." Some Poles have been deeply disappointed by the Obama administration's inaction on the issue, and believe this was an empty promise.[27]

"Polish death camps"

In May 2012, during Medal of Freedom Ceremony, Obama referred to the concentration camps run by Nazis in Poland during World War II as "Polish death camps," a term the Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk said showed "ignorance, lack of knowledge and ill will." Calling them "Polish death camps", Tusk said, implied that Poland was responsible and that "there had been no Nazis, no German responsibility, no Hitler."[28] After a White House spokesman issued a regret of misstatement by clarifying that the President was referring to the Nazi death camps, Tusk expressed an expectation of "a reaction more inclined to eliminate once and for all these kinds of errors."[29]

Images

Poland was one of the countries overrun by Nazi Germany. The country was recognized by the United States who issued this stamp in 1943 in Poland's honor.

Poland was one of the countries overrun by Nazi Germany. The country was recognized by the United States who issued this stamp in 1943 in Poland's honor. Polish President Lech Kaczyński shakes hands with United States President George W. Bush during their Joint Statement; Gdańsk, June 2007, during the G8 Summit 2007[30]

Polish President Lech Kaczyński shakes hands with United States President George W. Bush during their Joint Statement; Gdańsk, June 2007, during the G8 Summit 2007[30] Foreign Minister Sikorski meets US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, February 2009

Foreign Minister Sikorski meets US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, February 2009 United States President Barack Obama meeting with Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk in Warsaw, May 2011

United States President Barack Obama meeting with Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk in Warsaw, May 2011.jpg) Polish President Andrzej Duda meeting with United States President Donald J. Trump in Washington D.C., September 2018

Polish President Andrzej Duda meeting with United States President Donald J. Trump in Washington D.C., September 2018

High-level mutual visits

Visits from Poland to the United States

- Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski (1941, 1942, 1943)

- Prime Minister Stanisław Mikołajczyk (1944)

- First Secretary Edward Gierek (1974)

- Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki (1990)

- President Lech Wałęsa (1991, 1993)

- Prime Minister Jan Krzysztof Bielecki (1991)

- Prime Minister Jan Olszewski (1992)

- President Aleksander Kwaśniewski (1996, 1999, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005)

- Prime Minister Jerzy Buzek (1998, 1999)

- Prime Minister Leszek Miller (2002, 2003)

- Prime Minister Marek Belka (2004)

- President Lech Kaczyński (2006, 2007)

- Prime Minister Donald Tusk (2008)

- President Andrzej Duda (2018)

- Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki (2019)

- President Andrzej Duda (2019)

Visits from the United States to Poland

- President Richard Nixon (1972)

- President Gerald Ford (1975)

- President Jimmy Carter (1977)

- President George H. W. Bush (1989, 1992)

- President Bill Clinton (1994, 1997)

- President George W. Bush (2001, 2003, 2007)

- President Barack Obama (2011, 2014, 2016)

- President Donald Trump (2017)

- Vice President Mike Pence (2019)

Resident diplomatic missions

- Poland has an embassy in Washington, D.C. and consulates-general in Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles and New York.

- United States has an embassy in Warsaw and a consulate-general in Kraków.

Embassy of Poland in Washington, D.C.

Embassy of Poland in Washington, D.C.- Consulate-General of Poland in Chicago

Consulate-General of Poland in New York City

Consulate-General of Poland in New York City Embassy of the United States in Warsaw

Embassy of the United States in Warsaw Consulate-General of the United States in Kraków

Consulate-General of the United States in Kraków

See also

References

- "U.S. Relations With Poland".

- Opinion of the United States - Poland Pew Research Center

- U.S. Global Leadership Project Report - 2012 Gallup

- 2013 World Service Poll BBC

- #Jerzy Jan Lerski p. 26

- #Jerzy Jan Lerski p. 7.

- Stories of Poland. p. 141-142.

- #Jerzy Jan Lerski p. 32.

- "The Bilateral Effect of the Visit of the Russian Fleet in 1863". people.loyno.edu.

- Gregory F. Domber (2008). Supporting the Revolution: America, Democracy, and the End of the Cold War in Poland, 1981--1989. ProQuest. p. 199. ISBN 9780549385165., revised as Domber 2014, p. 110 .

- Domber, Gregory F. (28 August 2014), What Putin Misunderstands about American Power, University of California Press Blog, University of North Carolina PressCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cover Story: The Holy AllianceBy Carl Bernstein Sunday, June 24, 2001

- Branding Democracy: U.S. Regime Change in Post-Soviet Eastern Europe Gerald Sussman, page 128

- Looking to the Future: Essays on International Law in Honor of W. Michael Reisman

- Executive Secrets: Covert Action and the Presidency William J. Daugherty. page 201-203

- MacEachin, Douglas J. "US Intelligence and the Polish Crisis 1980–1981." CIA. June 28, 2008.

- Harper (May 6, 2016). "President Trump in Poland". Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- Rempfer, Kyle (29 May 2018). "Why Poland wants a permanent US military base, and is willing to pay $2 billion for it". Army Times. Vienna, Virginia. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- Zemla, Edyta; Turecki, Kamil (30 May 2018). "Poland offers US up to $2B for permanent military base". Politico.EU. Brussels. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- "Trump: US to send 1,000 troops to Poland in new deal". BBC. 12 June 2019.

- "US, Polish presidents sign pact to boost American military presence in Poland". DefenseNews. 24 September 2019.

- "Polish foreign minister says country's alliance with US worthless". The Guardian. 2014-06-22. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-05-02. Retrieved 2012-10-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Poland Agrees to Accept U.S. Missile Interceptors" by Peter Baker, The New York Times, October 21, 2009. Retrieved October 21, 2009.

- "Acting Secretary McAleenan Announces Designation of Poland into the Visa Waiver Program". Department of Homeland Security. 2019-11-06. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- David Harris (2011-10-18). "Bad idea to exclude Poland from U.S. Visa Waiver Program - Chicago Tribune". Articles.chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2012-09-30.

- "Tusk Demands U.S. Response to Obama Death Camp Remark". Bloomberg.

- "White House shrugs off Polish apology demands". Archived from the original on June 1, 2012.

- President Bush Participates in Joint Statement with President Kaczynski of Poland

- Janusz Reiter, The Visa Barrier, Washington Post, August 29, 2007

Further reading

- Biskupski, M.B.B. The United States and the Rebirth of Poland, 1914-1918 (2012)

- Biskupski, M.B.B. "Poland in American Foreign Policy, 1918-1945: "Sentimental" or "Strategic" Friendship?: A Review Article," Polish American Studies (1981) 38#2 pp. 5-15 in JSTOR

- Blejwas, Stanislaus A. "Puritans and Poles: The New England Literary Image of the Polish Peasant Immigrant." Polish American Studies (1985): 46-88. in JSTOR

- Cienciala, Anna M. "The United States and Poland in World War II." The Polish Review (2009): 173-194.

- Feis, Herbert. Churchill Roosevelt Stalin The War They Waged and the Peace They Sought A Diplomatic History of World War II (1957) ch 2, 7, 21, 29, 39-40, 54, 60; very detailed coverage

- Jaroszyźska-Kirchmann, Anna D. The Exile Mission: The Polish Political Diaspora and Political America, 1939–1956 (Ohio University Press, 2004).

- Jones, J. Sydney. "Polish Americans." Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 3, Gale, 2014), pp. 477-492. online

- Kantorosinski, Zbigniew. Emblem of Good Will: a Polish Declaration of Admiration and Friendship for the United States of America. Washington, DC: Library of Congress (1997)

- Lipoński, Wojciech. "Anti-American Propaganda in Poland From 1948 to 1954: A Story of An Ideological Failure." American Studies International (1990): 80-92. in JSTOR

- McGinley, Theresa Kurk. "Embattled Polonia, Polish-Americans and World War II." East European Quarterly (2003) 37#3 pp 325–344.

- Michalski, Artur. Poland’s Relations with the United States, Yearbook of Polish Foreign Policy (01/2005), CEEOL - Obsolete Link

- * Pacy, James S. "Polish Ambassadors and Ministers in Rome, Tokyo, and Washington, DC 1920-1945: Part II." The Polish Review (1985): 381-395.

- Halina Parafianowicz, Herbert C. Hoover and Poland: 1919–1933. Between Myth and Reality. in: Great Power Policies Towards Central Europe, 1914-1945. Bristol: e-International Relations, 2019: pp. 176–198. 1945 online free

- Pease, Neal. Poland, the United States, and the Stabilization of Europe, 1919-1933 (1986) excerpts

- Pienkos, Donald E. "Of Patriots and Presidents: America's Polish Diaspora and U.S. Foreign Policy Since 1917," Polish American Studies (2011) 68#1 pp. 5–17 in JSTOR

- Sjursen, Helene. The United States, Western Europe and the Polish Crisis: International Relations in the Second Cold War (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003)

- Wandycz, Piotr S. The United States and Poland (1980)