Semi-presidential system

A semi-presidential system or dual executive system is a system of government in which a president exists alongside a prime minister and a cabinet, with the latter being responsible to the legislature of the state. It differs from a parliamentary republic in that it has a popularly elected head of state, who is more than a mostly ceremonial figurehead, and from the presidential system in that the cabinet, although named by the president, is responsible to the legislature, which may force the cabinet to resign through a motion of no confidence.[1][2][3][4]

| |||||

| Systems of government | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

Primary topics |

|

Academic disciplines |

|

Organs of government |

| Politics Portal |

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Executive government |

|---|

| Head of state |

| Government |

|

| Systems |

| Lists |

| Politics portal |

While the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) exemplified an early semi-presidential system, the term "semi-presidential" was introduced in a 1959 article by journalist Hubert Beuve-Méry[5] and popularized by a 1978 work by political scientist Maurice Duverger,[6] both of which intended to describe the French Fifth Republic (established in 1958).[1][2][3][4]

Definition

Maurice Duverger's original definition of semi-presidentialism required that the president be elected, possess significant powers, and serve for a fixed term.[7] Modern definitions merely require that the head of state be elected and that a separate prime minister that is dependent on parliamentary confidence lead the executive.[7]

Subtypes

There are two separate subtypes of semi-presidentialism: premier-presidentialism and president-parliamentarism.

Under the premier-presidential system, the prime minister and cabinet are exclusively accountable to parliament. The president may choose the prime minister and cabinet, but only the parliament may approve them and remove them from office with a vote of no confidence. This system is much closer to pure parliamentarism. This subtype is used in Burkina Faso, Cape Verde,[8] East Timor,[8][9] Lithuania, Madagascar, Mali, Mongolia, Niger, Poland,[10] Portugal, Romania, São Tomé and Príncipe,[8] Sri Lanka and Ukraine (since 2014; previously, between 2006 and 2010).[11][12]

Under the president-parliamentary system, the prime minister and cabinet are dually accountable to the president and the parliament. The president chooses the prime minister and the cabinet but must have the support of a parliamentary majority for his choice. In order to remove a prime minister or the whole cabinet from power, the president can dismiss them, or the parliament can remove them by a vote of no confidence. This form of semi-presidentialism is much closer to pure presidentialism. It is used in Guinea-Bissau,[8] Mozambique, Namibia, Russia, Senegal and Taiwan. It was also used in Ukraine, first between 1996 and 2005, and again from 2010 to 2014, Georgia between 2004 and 2013, and in Germany during the Weimarer Republik (Weimar Republic), as the constitutional regime between 1919 and 1933 is called unofficially.[11][12]

Division of powers

The powers that are divided between president and prime minister can vary greatly between countries.

In France, for example, in case of cohabitation, when the president and the prime minister come from opposing parties, the president oversees foreign policy and defense policy (these are generally called les prérogatives présidentielles (the presidential prerogatives) and the prime minister domestic policy and economic policy.[13] In this case, the division of responsibilities between the prime minister and the president is not explicitly stated in the constitution, but has evolved as a political convention based on the constitutional principle that the prime minister is appointed (with the subsequent approval of a parliament majority) and dismissed by the president.[14] On the other hand, whenever the president is from the same party as the prime minister who leads the conseil de gouvernement (cabinet), he/she often (if not usually) exercises de facto control over all fields of policy via the prime minister. It is up to the president to decide how much "autonomy" is left to "their" prime minister to act on their own.

Cohabitation

Semi-presidential systems may sometimes experience periods in which the president and the prime minister are from differing political parties. This is called "cohabitation", a term which originated in France when the situation first arose in the 1980s. Cohabitation can create an effective system of checks and balances or a period of bitter and tense stonewalling, depending on the attitudes of the two leaders, the ideologies of themselves or their parties, or the demands of their constituencies.[15]

In most cases, cohabitation results from a system in which the two executives are not elected at the same time or for the same term. For example, in 1981, France elected both a Socialist president and legislature, which yielded a Socialist premier. But whereas the president's term of office was for seven years, the National Assembly only served for five. When, in the 1986 legislative election, the French people elected a right-of-centre assembly, Socialist President François Mitterrand was forced into cohabitation with right wing premier Jacques Chirac.[15]

However, in 2000, amendments to the French constitution reduced the length of the French president's term from seven to five years. This has significantly lowered the chances of cohabitation occurring, as parliamentary and presidential elections may now be conducted within a shorter span of each other.

Advantages and disadvantages

The incorporation of elements from both presidential and parliamentary republics brings some advantageous elements along with them but, however, it also faces disadvantages related to the confusion from mixed authority patterns.[16][17]

Advantages

- Providing cover for the president — it can shield the president from criticism and the unpopular policies can be blamed on the prime minister as the latter runs the day-to-day operations of the government and carrying out the national policy set forth by the president, who is the head of state that is focusing on being the national leader of a state and in arbitrating the efficiency of government authorities, etc.;

- Ability to remove an unpopular prime minister and maintain stability from the president's fixed term — the parliament has power to remove an unpopular prime minister;

- Additional checks and balances — while the president can dismiss the prime minister in many semi-presidential systems, in most of the semi-presidential systems important segments of bureaucracy are taken away from the president.

Disadvantages

- Confusion about accountability — parliamentary systems give voters a relatively clear sense of who is responsible for policy successes and failures; presidential systems make this more difficult, particularly when there is divided government. Semi-presidential systems add another layer of complexity for voters;

- Confusion and inefficiency in legislative process — the capacity of votes of confidence makes the prime minister responsible to the parliament.

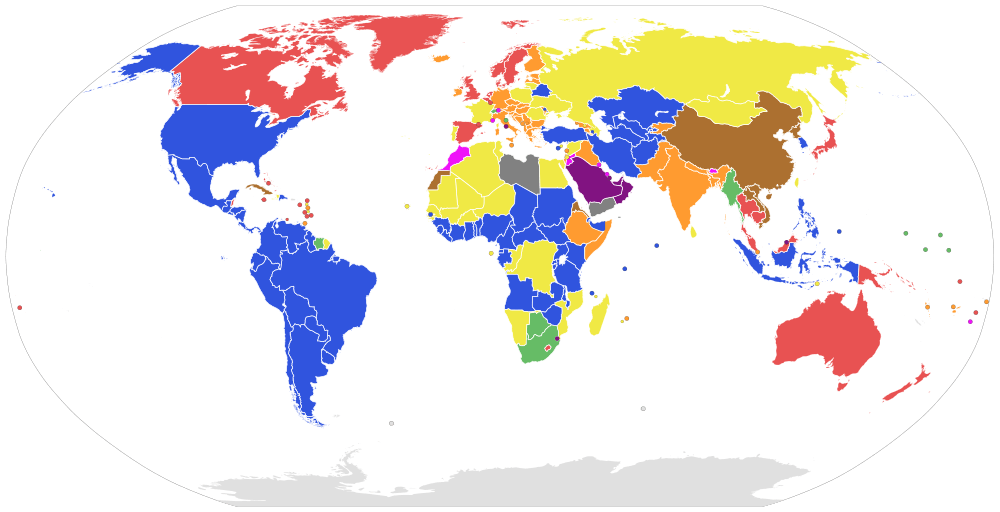

Republics with a semi-presidential system of government

In semi-presidential systems, there is always both a president and a prime minister. In such systems, the president has genuine executive authority, unlike in a parliamentary republic, but the role of a head of government may be exercised by the prime minister. Italics indicate states with limited recognition.

Premier-presidential systems

The president chooses the prime minister and cabinet, but only the parliament may remove them from office with a vote of no confidence. The president does not have the power to directly dismiss the prime minister or cabinet. But the president can dissolve the parliament.

President-parliamentary systems

The president chooses the prime minister without the confidence vote from the parliament. In order to remove a prime minister or the whole cabinet from power, the president can dismiss them or the parliament can remove them by a vote of no confidence, but the president can dissolve the parliament.

See also

Notes and references

- Duverger (1980). "A New Political System Model: Semi-Presidential Government". European Journal of Political Research (quarterly). 8 (2): 165–187. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00569.x.

The concept of a semi-presidential form of government, as used here, is defined only by the content of the constitution. A political regime is considered as semi-presidential if the constitution which established it, combines three elements: (1) the president of the republic is elected by universal suffrage, (2) he possesses quite considerable powers; (3) he has opposite him, however, a prime minister and ministers who possess executive and governmental power and can stay in office only if the parliament does not show its opposition to them.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Veser, Ernst (1997). "Semi-Presidentialism-Duverger's concept: A New Political System Model" (PDF). Journal for Humanities and Social Sciences. 11 (1): 39–60. Retrieved 21 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duverger, Maurice (September 1996). "Les monarchies républicaines" [The Republican Monarchies] (PDF). Pouvoirs, revue française d'études constitutionnelles et politiques (in French). No. 78. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. pp. 107–120. ISBN 2-02-030123-7. ISSN 0152-0768. OCLC 909782158. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- Bahro, Horst; Bayerlein, Bernhard H.; Veser, Ernst (October 1998). "Duverger's concept: Semi-presidential government revisited". European Journal of Political Research (quarterly). 34 (2): 201–224. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.00405.

The conventional analysis of government in democratic countries by political science and constitutional law starts from the traditional types of presidentialism and parliamentarism. There is, however, a general consensus that governments in the various countries work quite differently. This is why some authors have inserted distinctive features into their analytical approaches, at the same time maintaining the general dichotomy. Maurice Duverger, trying to explain the French Fifth Republic, found that this dichotomy was not adequate for this purpose. He therefore resorted to the concept of 'semi-presidential government': The characteristics of the concept are (Duverger 1974: 122, 1978: 28, 1980: 166):

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

1. the President of the Republic is elected by universal suffrage,

2. he possesses quite considerable powers and

3. he has opposite him a prime minister who possesses executive and governmental powers and can stay in office only if parliament does not express its opposition to him. - Le Monde, 8 January 1959.

- Duverger, Maurice (1978). Échec au roi. Paris: A. Michel. ISBN 9782226005809.

- Elgie, Robert (2 January 2013). "Presidentialism, Parliamentarism and Semi-Presidentialism: Bringing Parties Back In" (PDF). Government and Opposition. 46 (3): 392–409. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2011.01345.x.

- Neto, Octávio Amorim; Lobo, Marina Costa (2010). "Between Constitutional Diffusion and Local Politics: Semi-Presidentialism in Portuguese-Speaking Countries" (PDF). APSA 2010 Annual Meeting Paper. SSRN 1644026. Retrieved 18 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beuman, Lydia M. (2016). Political Institutions in East Timor: Semi-Presidentialism and Democratisation. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1317362128. LCCN 2015036590. OCLC 983148216. Retrieved 18 August 2017 – via Google Books.

- McMenamin, Iain. "Semi-Presidentialism and Democratisation in Poland" (PDF). School of Law and Government, Dublin City University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Shugart, Matthew Søberg (September 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive and Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies. United States: University of California, San Diego. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Shugart, Matthew Søberg (December 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive And Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies, University of California, San Diego. French Politics. 3 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200087. ISSN 1476-3427. OCLC 6895745903. Retrieved 12 October 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- See article 5, title II, of the French Constitution of 1958. Jean Massot, Quelle place la Constitution de 1958 accorde-t-elle au Président de la République?, Constitutional Council of France website (in French).

- Le Petit Larousse 2013 p. 880

- Poulard JV (Summer 1990). "The French Double Executive and the Experience of Cohabitation" (PDF). Political Science Quarterly (quarterly). 105 (2): 243–267. doi:10.2307/2151025. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2151025. OCLC 4951242513. Retrieved 7 October 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barrington, Lowell (1 January 2012). Comparative Politics: Structures and Choices. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1111341930 – via Google Books.

- Barrington, Lowell; Bosia, Michael J.; Bruhn, Kathleen; Giaimo, Susan; McHenry, Jr., Dean E. (2012) [2009]. Comparative Politics: Structures and Choices (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cenage Learning. pp. 169–170. ISBN 9781111341930. LCCN 2011942386. Retrieved 9 September 2017 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kudelia, Serhiy (4 May 2018). "Presidential activism and government termination in dual-executive Ukraine". Post-Soviet Affairs. 34 (4): 246–261. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2018.1465251.

- Bahro, Horst; Bayerlein, Bernhard H.; Veser, Ernst (October 1998). "Duverger's concept: Semi–presidential government revisited". European Journal of Political Research (quarterly). 34 (2): 201–224. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.00405.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beuman, Lydia M. (2016). Political Institutions in East Timor: Semi-Presidentialism and Democratisation. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1317362128. LCCN 2015036590 – via Google Books.

- Canas, Vitalino (2004). "The Semi-Presidential System" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht. 64 (1): 95–124.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duverger, Maurice (1978). Échec au roi. Paris: A. Michel. ISBN 9782226005809.

- Duverger, Maurice (June 1980). "A New Political System Model: Semi-Presidential Government". European Journal of Political Research (quarterly). 8 (2): 165–187. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00569.x.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Elgie, Robert (2011). Semi-Presidentialism: Sub-Types And Democratic Performance. Comparative Politics. (Oxford Scholarship Online Politics) OUP Oxford ISBN 9780199585984

- Frye, Timothy (October 1997). "A Politics of Institutional Choice: Post-Communist Presidencies" (PDF). Comparative Political Studies. 30 (5): 523–552. doi:10.1177/0010414097030005001.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goetz, Klaus H. (2006). Heywood, Paul; Jones, Erik; Rhodes, Martin; Sedelmeier (eds.). Developments in European politics. Power at the Centre: The Organization of Democratic Systems. Basingstoke England New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 368. ISBN 9780230000414.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lijphart, Arend (1992). Parliamentary versus presidential government. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198780441.

- Nousiainen, Jaakko (June 2001). "From Semi-presidentialism to Parliamentary Government: Political and Constitutional Developments in Finland". Scandinavian Political Studies (quarterly). 24 (2): 95–109. doi:10.1111/1467-9477.00048. ISSN 0080-6757. OCLC 715091099.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Passarelli, Gianluca (December 2010). "The government in two semi-presidential systems: France and Portugal in a comparative perspective" (PDF). French Politics. 8 (4): 402–428. doi:10.1057/fp.2010.21. ISSN 1476-3427. OCLC 300271555.

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (1995). "From Prime Ministerial power to core executive". In Rhodes, R. A. W.; Dunleavy, Patrick (eds.). Prime minister, cabinet, and core executive. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 11–37. ISBN 9780333555286.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roper, Steven D. (April 2002). "Are All Semipresidential Regimes the Same? A Comparison of Premier-Presidential Regimes". Comparative Politics. 34 (3): 253–272. doi:10.2307/4146953. JSTOR 4146953.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sartori, Giovanni (1997). Comparative constitutional engineering: an inquiry into structures, incentives, and outcomes (2nd ed.). Washington Square, New York: New York University Press. ISBN 9780333675090.

- Shoesmith, Dennis (March–April 2003). "Timor-Leste: Divided Leadership in a Semi-Presidential System". Asian Survey (bimonthly). 43 (2): 231–252. doi:10.1525/as.2003.43.2.231. ISSN 0004-4687. OCLC 905451085.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shugart, Matthew Søberg (September 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive and Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies. United States: University of California, San Diego. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Shugart, Matthew Søberg (December 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive And Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies, University of California, San Diego. French Politics. 3 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200087. ISSN 1476-3427. OCLC 6895745903.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shugart, Matthew Søberg; Carey, John M. (1992). Presidents and assemblies: constitutional design and electoral dynamics. Cambridge England New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521429900.

- Veser, Ernst (1997). "Semi-Presidentialism-Duverger's concept: A New Political System Model" (PDF). Journal for Humanities and Social Sciences. 11 (1): 39–60.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Notes

- In France, the President chooses (if he hasn't a majority in the National Assembly, he has to choose the leader of the opposition) but can only dismiss the Prime Minister if he/she has a majority in the National Assembly. The National Assembly can remove the Prime Minister from office with a vote of no confidence. The president can also dissolve the National Assembly once a year.

- Following the 19th amendment, Sri Lankan president can only appoint the prime minister following vacating of the position due to loss of confidence of Parliament, death or resignation. And does not hold the power to dismiss the prime minister at will.

External links

- Governing Systems and Executive-Legislative Relations. (Presidential, Parliamentary and Hybrid Systems), United Nations Development Programme (n.d.). Archived 10 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- J. Kristiadi (April 22, 2008). "Indonesia Outlook 2007: Toward strong, democratic governance". The Jakarta Post. PT Bina Media Tenggara. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008.

- The Semi-Presidential One, blog of Robert Elgie

- Presidential Power blog with posts written by several political scientists, including Robert Elgie.