Ghazan

Mahmud Ghazan (1271– 11 May 1304) (Mongolian: Газан хаан, Persian: غازان خان, Ghazan Khan, sometimes referred to as Casanus by Westerners[2]) was the seventh ruler of the Mongol Empire's Ilkhanate division in modern-day Iran from 1295 to 1304. He was the son of Arghun, grandson of Abaqa Khan and great-grandson of Hulagu Khan continuing a long line of rulers who were direct descendants of Genghis Khan. Considered the most prominent of the Ilkhans, he is best known for making a political conversion to Islam and meeting Imam Ibn Taymiyya in 1295 when he took the throne, marking a turning point for the dominant religion of Mongols in Western Asia (Iran, Iraq, Anatolia and Transcaucasia). One of the many principal wives of him was Kököchin, a Mongol princess (originally betrothed to Ghazan's father Arghun before his death) sent by his great-uncle Kublai Khan.

| Ghazan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khan Pādeshāh of Iran and Islam[1] | |||||

| Ilkhan | |||||

| Reign | 4 October 1295 – 11 May 1304 | ||||

| Coronation | 19 October 1295 | ||||

| Predecessor | Baydu | ||||

| Successor | Öljeitü | ||||

| Naib | Nawruz | ||||

| Viceroy of Khorasan | |||||

| Reign | 1284 - 1295 | ||||

| Predecessor | Arghun | ||||

| Successor | Nirun Aqa | ||||

| Born | 5 November 1271 Abaskun, Ilkhanate | ||||

| Died | 17 May 1304 (aged 32) Qazvin, Ilkhanate | ||||

| Consort | Yedi Kurtka Khatun Bulughan Khatun Khurasani Kököchin Bulughan Khatun Muazzama Eshil Khatun Dondi Khatun Karamun Khatun | ||||

| |||||

| Father | Arghun | ||||

| Mother | Kultak egechi | ||||

| Religion | Buddhism after 1295 Sunni Islam | ||||

Military conflicts during Ghazan's reign included war with the Egyptian Mamluks for control of Syria, and battles with the Turko-Mongol Chagatai Khanate. Ghazan also pursued diplomatic contacts with Europe, continuing his predecessors' unsuccessful attempts at forming a Franco-Mongol alliance. A man of high culture, Ghazan spoke multiple languages, had many hobbies, and reformed many elements of the Ilkhanate, especially in the matter of standardizing currency and fiscal policy.

Childhood

Ghazan's parents were Arghun and his concubine Kultak egechi of the Dörben tribe. At time of their marriage Arghun was 12. Kultak's elder sister Ashlun was the wife of Tübshin, son of Hulagu and previous viceroy in Khorasan. According to Rashid al-Din, marriage took place in Mazandaran, where Arghun was viceroy.[3] Ghazan was born on 5 November 1271 in Abaskun (near modern Bandar Turkman) though he was raised in the Ordo (nomadic palace-tent) of his grandfather Abaqa's favorite wife, Buluqhan Khatun, who herself was childless.[4] Ghazan and Arghun didn't see each other until Abaqa's attack on Qaraunas in 1279 where they briefly met.

Ghazan was raised Buddhist,[5] as was his brother Oljeitu. The Mongols were traditionally tolerant of multiple religions, and during Ghazan's youth, he was educated by a Chinese monk, who taught him Buddhism, as well as the Mongolian and Uighur scripts.[6]

Under Tekuder

He lived together with Gaykhatu in Buluqhan Khatun's encampment in Baghdad after Abaqa's death. He reunited again with his father when Buluqhan khatun wed to Arghun and became Ghazan's step-mother.

Rule in Khorasan

Under Arghun

After the overthrow of Tekuder in 1284, Ghazan's father Arghun was enthroned as Ilkhan, the 11-year-old Ghazan became viceroy, and he moved to the capital of Khorasan, never to see Arghun again. Emir Tegene was appointed as his deputy, whom he didn't like very much. In 1289, conflict with other Mongols ensued when a revolt was led against Arghun by Nawruz, a young emir of the Oirat clan, whose father had been civil governor of Persia before the arrival of Hulagu. Ghazan's deputy Tegene was among victims of Nawruz's raid on 20 April 1289 in which he was captured and imprisoned. Nawruz's protege, Prince Hulachu was arrested by Ghazan's commander Mulay ten days later.[7] When Nawruz was defeated by Arghun's reinforcements in 1290,[8] fled the Ilkhanate and joined the alliance of Kaidu, another descendant of Genghis Khan who was the ruler of both the House of Ögedei and the neighboring Chagatai Khanate. Ghazan spent the next ten years defending the frontier of the Ilkhanate against incursions by the Chagatai Khanate of Central Asia.

Under Gaykhatu

When his father, Arghun, died in 1291, Ghazan was prevented from pursuing his claim of leadership in the capital because he was engaged both with Nawruz's raids, and dealing with rebellion and famine in Khorasan and Nishapur. Taghachar, an army commander who had served the previous three generations of Ilkhans, was probably behind the death of Arghun, and supported Ghazan's uncle Gaykhatu as the new Ilkhan.[9] Despite being boyhood rivals, Gaykhatu sent aid to Ghazan's fight against Nawruz in Khorasan under leadership of Prince Anbarchi (son of Möngke Temür) and emirs Tuladai, Quncuqbal and El Temür; himself going to Anatolia to quell Turcoman uprisings. However, famine reached his court too in spring and Anbarchi, unable to feed his soldiers, had to leave soon for Azerbaijan again. He again tried to visit Gaykhatu, but after his refusal, he had to go back. Ghazan received Kököchin, a 13th-century Mongol princess from the Yuan dynasty in China, on his way back from Tabriz to Khorasan. She had been brought from the east in a caravan which included Marco Polo among hundreds of other travellers. She had originally been betrothed to Ghazan's father, the Ilkhan Arghun, but since he had died during her months-long journey, she instead married his son Ghazan.[10]

In 1294, Ghazan forced Nawruz to surrender at Nishapur[11] and Nawruz then became one of Ghazan's lieutenants. Ghazan was loyal to his uncle, though he refused to follow Gaykhatu's lead in introducing paper currency to his province, explaining that the weather of Khorasan was too humid to handle paper.[12]

Against Baydu

In 1295, Taghachar and his conspirators, who probably had been behind the death of Arghun, had his successor Gaykhatu killed as well. They then placed the controllable Baydu, a cousin of Ghazan, on the throne. Baydu was primarily a figurehead, allowing the conspirators to divide the Ilkhanate among themselves. Hearing Gaykhatu's murder, Ghazan marched on Baydu. Baydu explained the fact that Ghazan was away during events leading to Gaykhatu's fall, therefore nobles had no choice but to raise him to throne.[13] Nevertheless, Amir Nowruz encouraged Ghazan to take steps against Baydu, because he was nothing but a figurehead under grips of nobles. Baydu's forces commanded by Ildar (his cousin and Prince Ajay's son), Eljidei and Chichak met him near Qazvin. Ghazan's army were commanded by Prince Sogai (son of Yoshmut), Buralghi, Nowruz, Qutluqshah and Nurin Aqa. First battle was won by Ghazan but he had to fall back after realising Ildar's contingent was just a fraction of whole army, leaving Nowruz behind. Nevertheless, he captured Arslan, a descendant of Jochi Qasar.[14]

After a short truce, Baydu offered Ghazan co-ruling of ilkhanate and Nowruz the post of sahib-i divan to which as a counter-condition Ghazan demanded the revenues of his father's hereditary lands in Fars, Persian Iraq and Kerman. Nowruz denied conditions, which led to its arrest. According to an anecdote, he promised to bring Ghazan back tied-up on condition of his release. Once he reached Ghazan, he sent back a cauldron to Baydu; a word play on the Turkish word kazan. Nowruz promised him the throne and his help on a condition of Ghazan's conversion to Islam. Ghazan converted to Islam, on June 16, 1295,[15] at the hands of Ibrahim ibn Muhammad ibn al-Mu'ayyid ibn Hamaweyh al-Khurasani al-Juwayni[16] as a condition for Nawruz's military support.[17] Nowruz entered Qazvin with 4000 soldiers and claimed an additional number of 120.000 soldiers commanded by Ebügen (in other sources, 30.000)[18] - descendant of Jochi Qasar - on his way towards Azerbaijan which caused panic among masses which was followed by defections of Taghachar's subordinates (thanks to Taghachar's vizier Sadr ul-Din Zanjani) and other powerful emirs like Qurumishi and Chupan on 28 August 1295.

Seeing imminent defeat, Baydu asked for Taghachar's support, ignorant of his defection. After realising Taghachar's withraw, he fled to Emir Tukal in Georgia on 26 September 1295. Ghazan's commanders found him near Nakhchivan and arrested him, taking back to Tabriz, having him executed on October 4, 1295.

Early reign

He declared his victory after execution of Baydu in outskirts of Tabriz on 4 October 1295,[19] he entered the city. After declaration, several appointments, orders and executions came as usual - Gaykhatu's son Alafrang's son-in-law Eljidai Qushchi was executed, Nawruz was rewarded with naibate of state and was given extreme power, akin to Buqa's back in the day of Arghun. Nawruz on his part issued a formal edict in opposition to other religions in the Ilkhanate. Nawruz loyalists persecuted Buddhists and Christians to such an extent that Iranian Buddhism never recovered,[20] the Nestorian cathedral in the Mongol capital of Maragha was looted, and churches in Tabriz and Hamadan were destroyed. Baydu loyalists too were purged - emirs Jirghadai and Qoncuqbal were executed on 10 and 15 October respectively. Qoncuqbal was specifically hated for his murder of Aq Buqa Jalair, his executioner was Nawruz's brother Hajji, who was also Aq Buqa's son-in-law.[21] Taghachar's protege, Sadr ul-Din Zanjani was granted the office of vizierate, following deposition of Baydu's vizier Jamal ud-Din. He re-appointed Taghachar to Anatolian viceroyalty on 10 November 1295. Another series of executions came after 1296: Prince Ajai's son Ildar fled to Anatolia on 6 February but was captured and executed;[22] Yesütai, an Oirat commander who supported Hulagu's son-in-law Taraghai in his migration to Mamluk Syria was executed on 24 May and Buralghi Qiyatai, a commander who was rebellious against Arghun was executed on 12 February.

Meanwhile Nogai, kingmaker in Golden Horde was murdered and his wife Chubei fled to Ghazan with his son Torai[23] (or Büri[24]) who was Abaqa's son-in-law in 1296.

Purge of nobles

Ghazan eased the troubles with the Golden Horde, but the Ögedeids and Chagataids in Central Asia continued to pose a serious threat to both the Ilkhanate and his overlord and ally the Great Khan in China. When Ghazan was crowned, the Chagatayid Khan Duwa invaded Khorasan on 9 December 1295. Ghazan sent two of his relatives - Prince Sogai (son of Yoshmut) and Esen Temür (son of Qonqurtai) against the army of Chagatai Khanate but they deserted, believing this was Nawruz's plot further deprive nobility of their possessions.[25] Nawruz informed Ghazan of this plot, subsequently executed them in 1296. Another Borjigid prince, Arslan who was captured by Ghazan previously and pardoned, revolted in Bilasuvar. After series of battles near Baylaqan he too was captured and executed alongside with rebellious emirs on 29 March.

Following purge of princes, Taghachar was thought to have been implicated in the rebellion of Prince Sogai and was declared a rebel.[26] Taghachar strengthened himself in Tokat and resisted against Ghazan's commanders Harmanji, Baltu and Arap (son of Samagar). He was soon arrested by Baltu near Delice and was delivered to Ghazan in 1296. Shortly afterwards Ghazan reluctantly ordered the murder of Taghachar; he recognised that he had been a help and that he was not an imminent threat, and explained his decision by reference to Chinese story about execution of a commander who saved a future emperor by betraying a former one.[27] His protege Sadr ul-Din Zanjani was revoked from vizierate and arrested in March 1296, but pardoned thanks to intervention of Buluqhan Khatun.

Purges were followed by executions of Chormaqan's grandson Baighut on 7 September 1296, Hazaraspid ruler Afrasiab I in October 1296, Baydu's vizier Jamal ud-Din Dastgerdani on 27 October 1296.

Revolt of Baltu

Taghachar's death triggered revolts of Baltu of the Jalayir in Anatolia where he was stationed since Abaqa's reign. He was supported by Ildar (son of Qonqurtai), who was arrested and executed in September 1296. Two months later, Qutluqshah invaded Anatolia with 30.000 men and crushed Baltu's revolt, arresting him in June. He was brought to Tabriz and jailed there until 14 September 1297, when he was executed along with his son. Seljuk Sultan of Rum Mesud II on the other hand was arrested and jailed in Hamadan.[26]

Fall of Nawruz

Nawruz soon embroiled himself in argument with Nurin Aqa, who was more popular in military and left Khorasan. After returning to west, he survived an assassination attempt by a soldier named Tuqtay, who claimed that Nawruz murdered his own father, Arghun Aqa. Soon he was accused of treason by Sadr al-Din Khaladi, sahib-divan of Ghazan by secret alliance with Mamlukes. Indeed, according to Mamluk sources, Nawruz corresponded with Sultan Lajin.[29] Using opportunity Ghazan started a purge against Nawruz and his followers in May 1297. His brother Hajji Narin and his follower Satalmish were executed among Nawruz's children in Hamadan, his other brother Lagzi Güregen was also put to death in Iraq on 2 April 1297. His 12 year old son Toghai was spared due to efforts of Bulughan Khatun Khurasani, Ghazan's wife Arghun Aqa's granddaughter and given to household of Amir Husayn. Along spared, were his brother Yol Qutluq and his nephew Kuchluk. Later that year Ghazan marched against Nawrūz himself, who at the time was the commander of the army of Khorassan. Ghazan's forces were victorious at a battle near Nishapur. Nawrūz took refuge at the court of the Malik (king) of Herat in northern Afghanistan, but the Malik betrayed him and delivered Nawruz to Qutlughshah, who had Nawruz executed immediately on August 13.[30]

Relationship with other Mongol khanates

Ghazan maintained strong ties with the Great Khan of the Yuan and the Golden Horde. In 1296 Temür Khan, the successor of the Kublai Khan, dispatched a military commander Baiju to Mongol Persia.[31] Five years later Ghazan sent his Mongolian and Persian retainers to collect income from Hulagu's holdings in China. While there, they presented tribute to Temür and were involved in cultural exchanges across Mongol Eurasia.[32] Ghazan also called upon other Mongol Khans to unite their will under the Temür Khan, in which he was supported by Kaidu's enemy Bayan Khan of the White Horde. Ghazan's court had Chinese physicians present.[33]

Later reign

In order to stabilize the country Ghazan attempted to control the situation[34] and continued the executions - Taiju (son of Möngke Temür) on 15 April 1298 on charges of sedition, vizier Sadr ul-Din Zanjani on 4 May and his brother Qutb ul-Din and with cousin Qawam ul-Mulk on 3 June on charges of embezzlement, Abu Bakr Dadqabadi on 10 October. Ghazan appointed a Jewish convert to Islam - Rashid-al-Din Hamadani as new vizier succeeding Sadr ul-Din Zanjani, a post which Rashid held for the next 20 years, until 1318.[30] Ghazan also commissioned Rashid-al-Din to produce a history of the Mongols and their dynasty, the Jami' al-tawarikh "Compendium of Chronicles" or Universal History. Over several years of expansion, the work grew to cover the entire history of the world since the time of Adam, and was completed during the reign of Ghazan's successor, Oljeitu. Many copies were made, a few of which survive to the modern day.

After Taiju's execution, he appointed Nurin Aqa as viceroy of Arran on 11 September 1298.

Revolt of Sulemish

Sulemish (grandson of Baiju), whom Qutlughshah appointed as viceroy in Anatolia after Baltu's revolt, rebelled himself in 1299. Assembling a force of 20.000 strong army which postponed Ghazan's plan to invade Syria. Qutlugshah was forced to come back from Arran and won a victory against him, on 27 April 1299 near Erzinjan, causing rebel to flee to Mamluk Egypt. He returned with the Mamluk reinforcements to Anatolia but defeated again. He was brought to Tabriz and executed by burning on 27 September 1299.[26]

Mamluk-Ilkhanid War

Ghazan was one of a long line of Mongol leaders who engaged in diplomatic communications with the Europeans and Crusaders in attempts to form a Franco-Mongol alliance against their common enemy, primarily the Egyptian Mamluks. He already had the use of forces from Christian vassal countries such as Cilician Armenia and Georgia. The plan was to coordinate actions between Ghazan's forces, the Christian military orders, and the aristocracy of Cyprus to defeat the Egyptians, after which Jerusalem would be returned to the Europeans.[35] Many Europeans are known to have worked for Ghazan, such as Isol the Pisan or Buscarello de Ghizolfi, often in high positions. Hundreds of such Western adventurers entered into the service of Mongol rulers.[36] According to historian Peter Jackson, the 14th century saw such a vogue of Mongol things in the West that many new-born children in Italy were named after Mongol rulers, including Ghazan: names such as Can Grande ("Great Khan"), Alaone (Hulagu, Ghazan's great-grandfather), Argone (Arghun, Ghazan's father) or Cassano (Ghazan) were recorded with a high frequency.[37]

In October 1299, Ghazan marched with his forces towards Syria and invited the Christians to join him.[38] His army took the city of Aleppo, and was there joined by his vassal King Hethum II of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, whose forces included some Templars and Hospitallers, and who participated in the rest of the offensive.[39] The Mongols and their allies defeated the Mamluks in the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar, on December 23 or 24, 1299.[40] One group of Mongols then split off from Ghazan's army and pursued the retreating Mamluk troops as far as Gaza,[41] pushing them back to Egypt. The bulk of Ghazan's forces proceeded to Damascus, which surrendered somewhere between December 30, 1299, and January 6, 1300, though its Citadel resisted.[40][42][43] Most of Ghazan's forces then retreated in February, probably because their horses needed fodder. He promised to return in the winter of 1300–1301 to attack Egypt.[44][45] About 10,000 horsemen under the Mongol general Mulay were left to briefly rule Syria, before they too retreated.[46]

Ghazan was indeed feared and despised by the Mamluks, who sent a delegation of leading scholars and imams including Ibn Taymiyya, north from Damascus to al-Nabk, where Ghazan was encamped, in January 1300, in order to persuade Ghazan to stop his attack on Damascus. Ibn Taymiyya also may have met Ghazan in Damascus in August 1301.[47] On one of these occasions, it is reported that not one of the scholars dared to say anything to Ghazan except Ibn Taymiyyah who said:

"You claim that you are Muslim and you have with you Mu'adhdhins, Muftis, Imams and Shaykhs but you invaded us and reached our country for what? Although your father and your grandfather, Hulagu were non-believers, they did not attack us and they kept their promise. But you promised and broke your promise."

It is reported on the Mu'jamus Shuyuukh, Ibn Hajar Al-Asqalani said that Mongol leader who was apostate when he struggled against Mamluks and he converted to Christianity and built the Nestorian Cathedral to dedicated himself. He prefer to ally with Crusade Nations and he had chosen to attack Mamluks army and slaughtered them. The Mongol leader none other than was Ghazan Khan.

In July 1300, the Crusaders formed a small fleet of sixteen galleys with some smaller vessels to raid the coast, and Ghazan's ambassador traveled with them.[48][49] The Crusader forces also attempted to establish a base at the small island of Ruad, from which raids were launched on Tartus while awaiting Ghazan's forces. However, the Mongol army was delayed, and the Crusader forces retreated to Cyprus, leaving a garrison on Ruad which was besieged and captured by Mamluks by 1303 (see Siege of Ruad).

In February 1301, the Mongols advanced again with a force of 60,000, but could do little else than engage in some raids around Syria. Ghazan's general Kutlushah stationed 20,000 horsemen in the Jordan Valley to protect Damascus, where a Mongol governor was stationed.[51] But again, they were soon forced to withdraw.

Plans for combined operations with the Crusaders were again made for the following winter offensive, and in late 1301, Ghazan asked Pope Boniface VIII to send troops, priests, and peasants, in order to make the Holy Land a Frank state again.[51] But again, Ghazan did not appear with his own troops. He wrote again to the Pope in 1302, and his ambassadors also visited the court of Charles II of Anjou, who on April 27, 1303 sent Gualterius de Lavendel as his own ambassador back to Ghazan's court.[52]

In 1303, Ghazan sent another letter to Edward I via Buscarello de Ghizolfi, reiterating his great-grandfather Hulagu Khan's promise that the Mongols would give Jerusalem to the Franks in exchange for help against the Mamluks.[53] The Mongols, along with their Armenian vassals, had mustered a force of about 80,000 to repel the raiders of the Chagatai Khanate, which was under the leadership of Qutlugh Khwaja.[54] After their success there, they advanced again towards Syria. However, Ghazan's forces were utterly defeated by the Mamluks just south of Damascus at the decisive Battle of Marj al-Saffar in April 1303.[55] It was to be the last major Mongol invasion of Syria.[56]

End of reign

After military campaigns, Ghazan returned to his capital Ujan in July 1302 and made several appointments: Nirun Aqa and Öljaitü were reconfirmed in Arran and Khorasan as viceroys respectively, while Mulay was sent to Diyar Bakr and Qutluqshah was assigned to Georgia. He received a concubine from Andronikos II Palaiologos in 1302, who may be the Despina Khatun that later married to Öljaitü.[57] On 17 September 1303, Ghazan betrothed his daughter Öljei Qutlugh to Bistam, son of his brother Öljaitü.[58]

According to Rashid al-Din, Ghazan became depressed after his wife Karamun's death on 21 January. He once told his amirs that "life was a prison... and is not a benefit".[59] Later in March/April, he nominated his brother Öljaitü as his successor, as he had no son his own. Eventually, he died on 17 May 1304 near Qazvin. He was bathed in the water of Lar Damavand valley of Mazandaran.

Legacy

Religious policy

As part of his conversion to Islam, Ghazan changed his first name to the Islamic Mahmud, and Islam gained popularity within Mongol territories. He showed tolerance for multiple religions, encouraged the original archaic Mongol culture to flourish, tolerated the Shiites, and respected the religions of his Georgian and Armenian vassals. Ghazan therefore continued his forefather's approach toward religious tolerance. When Ghazan learned that some Buddhist monks feigned conversion to Islam due to their temples being earlier destroyed, he granted permission to all who wished to return to Tibet, Kashmir or India where they could freely follow their faith and be among other Buddhists.[60] The Mongol Yassa code remained in place and Mongol shamans remained politically influential throughout the reign of both Ghazan and his brother and successor Oljeitu, but ancient Mongol traditions eventually went into decline after Oljeitu's demise.[61] Other religious upheaval in the Ilkhanate during Ghazan's reign was instigated by Nawruz, Ghazan put a stop to these exactions by issuing an edict exempting the Christians from the jizya (tax on non-Muslims),[62] and re-established the Christian Patriarch Mar Yaballaha III in 1296. Ghazan reportedly punished religious fanatics who destroyed churches and synagogues in Tabriz on 21 July 1298.[63]

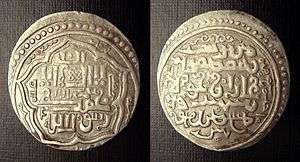

Obv: Arabic: لاإله إلا الله محمد رسول الله صلى الله عليه وسلم/ ضرب تبريز/ في سنة سبع ...ر, romanized: Lā ilāha illa llāha Muḥammadun rasūlu llāhi ṣalla llāhu ʽalayhi wa-sallam / ḍuriba Tabrīz / fī sanati sabʽin ..., lit. 'There is no God but Allah, Muhammad is His Prophet, Peace be upon him/ Minted in Tabriz in the year ...7' : ""

Rev: Legend in Mongolian script (except for "Ghazan Mahmud" in Arabic): Tengri-yin Küchündür. Ghazan Mahmud. Ghasanu Deledkegülügsen: "By the strength of the Heaven/ Ghazan Mahmud/ Coin struck for Ghazan".

Tabriz mint. 4.0 gr (0.26 g). Silver.

Reforms

Ghazan was a man of high culture, with many hobbies including linguistics, agro-techniques, painting, and chemistry. According to the Byzantine historian Pachymeres (1242–1310): "No one surpassed him, in making saddles, bridles, spurs, greaves and helmets; he could hammer, stitch and polish, and in such occupations employed the hours of his leisure from war."[65] Ghazan spoke numerous languages, including Chinese, Arabic, and "Frank" (probably Latin), as well as his own native language Mongolian.[66]

In addition to his religious deep impact on Persia, Ghazan had unified measures, coinage and weights in the Ilkhanate. He ordered a new census in Persia to define the Dynasty's fiscal policy. He began to reuse wilderness, non-producing and abandoned lands to raise crops, strongly supporting the use and introduction of Eastern Asian crops in Persia, and improved the Yam system. He constructed hostels, hospitals, schools, and posts. Envoys from the court received a per diem stipend, and those of the nobility traveled at their own expense. Ghazan ordered only envoys bearing urgent military intelligence to use the staffed postal relay service. Mongol soldiers were given iqtas by the Ilkhanid court, where they were allowed to gather revenue provided by a piece of land. Ghazan also banned lending at interest.[67]

Ghazan reformed the issuance of jarliqs (edicts), creating set forms and graded seals, ordering that all jarliqs be kept on file at court. Jarliqs older than 30 years were to be cancelled, along with old paizas (Mongol seals of authority). He fashioned new paizas into two ranks, which contained the names of the bearers on them to prevent them from being transferred. Old paizas were also to be turned in at the end of the official's term.

In fiscal policy, Ghazan introduced a unified bi-metallic currency including Ghazani dinars, and reformed purchasing procedures, replacing the traditional Mongol policy on craftsmen in the Ilkhanate, such as organizing purchases of raw materials and payment to artisans. He also opted to purchase most weapons on the open market.

On coins, Ghazan omitted the name of the Great Khan, instead inscribing his own name upon his coins in Iran and Anatolia. But he continued to diplomatic and economic relations with the Great Khan at Dadu.[68] In Georgia, he minted coins with the traditional Mongolian formula "Struck by the Ilkhan Ghazan in the name of Khagan" because he wanted to secure his claim on the Caucasus with the help of the Great Khans of the Yuan Dynasty.[69] He also continued to use the Great Khan's Chinese seal which declared him to be a wang (prince) below the Great Khan.[70]

His reforms also extended to the military, as several new guard units, mostly Mongols, were created by Ghazan for his army center. However, he restricted new guards' political significance. Seeing Mongol commoners selling their children into slavery as damaging to both the manpower and the prestige of the Mongol army, Ghazan budgeted funds to redeem Mongol slave boys, and made his minister Bolad (the ambassador of the Great Khan Kublai) commander of a military unit of redeemed Mongol slaves.

Family

Ghazan had nine wives, 5 of them being principal wives and one being concubine:

- Yedi Kurtka Khatun — daughter of Möngke Temür Güregen (from Suldus tribe) and Tuglughshah Khatun (daughter of Qara Hülegü)

- Bulughan Khatun Khurasani — daughter of Amir Tasu (from Eljigin clan of Khongirad) and Menglitegin, daughter of Arghun Aqa

- A stillborn son (born 1291 in Damavand)

- Kököchin Khatun (b. 1269, m. 1293 at Abhar, d. 1296) — relative of Buluqhan Khatun

- Bulughan Khatun Muazzama (m. 17 October 1295 at Tabriz, d. 5 January 1310) — daughter of Otman Noyan (from Khongirad tribe), widow of Gaykhatu and Arghun

- Uljay Qutlugh Khatun — married firstly to Bistam, son of Öljaitü, married secondly to his brother Abu Sa'id

- Alju (b. 22 February 1298 in Arran - 20 August 1300 in Tabriz)

- Eshil Khatun (betrothed in 1293, married on 2 July 1296 at Tabriz) — daughter of Tugh Timur Amir-Tüman (son of Noqai Yarghuchi of Bayauts)

- Dondi Khatun (d. 9 February 1298) — daughter of Aq Buqa (from Jalayir tribe), widow of Gaykhatu

- Karamün Khatun (m. 17 July 1299, d. 21 January 1304) — daughter of Qutlugh Temür (cousin of Bulughan Khatun Muazzama, from Khongirad tribe)

- Günjishkab Khatun — daughter of Shadai Güregen (great-grandson of Chilaun) and Orghudaq Khatun (daughter of Jumghur)

- A daughter of Andronikos II Palaiologos[57] (married in 1302)

Notes

- Fragner, Bert G. (2013). "Ilkhanid rule and its contributions to Iranian political culture". In Komaroff, Linda (ed.). Beyond the legacy of Genghis Khan. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Brill. p. 73. ISBN 978-90-474-1857-3. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

When Ghazan Khan embraced Islam and proclaimed himself "pādishāh-i Īrān wa Islām" at the end of the thirteenth century (...)

- Schein, p. 806.

- Hamadani, p. 590

- Rashid al-Din – Universal history

- "Ghazan had been baptized and raised a Christian"Richard Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition, 2010, p. 120 ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1

- Charles Melville, "Padshah-i Islam: the conversion of Sultan Mahmud Ghazan Khan, pp. 159–177"

- Hamadani, p. 596

- Hope, Michael (October 2015). "The "Nawrūz King": the rebellion of Amir Nawrūz in Khurasan (688–694/1289–94) and its implications for the Ilkhan polity at the end of the thirteenth century". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 78 (3): 451–473. doi:10.1017/S0041977X15000464. ISSN 0041-977X.

- Rashid al Din – Ibid, pp. I,d.III

- Marco Polo, Giovanni Battista Baldelli Boni, Hugh Murray, Société de géographie (France)-The Travels of Marco Polo.

- Jackson, p. 170.

- René Grousset The Empire of Steppes.

- Hope, p. 148

- Hamadani, p. 614

- A. S. Atiya (January 1965). The Crusade in the Later Middle Ages. p. 256. ISBN 9780527037000.

- Tadhkirat Al-huffaz of Al-Dhahabi

- Amir Nawruz was a Muslim, and offered the support of a Muslim army if Ghazan would promise to embrace Islam in the event of his victory over Baidu" Foltz, p. 128.

- Hamadani, p. 623

- Fisher, p. 379

- Roux, p. 430.

- Hamadani, p. 629

- "Mediating Sacred Kingship: Conversion and Sovereignty in Mongol Iran". hdl:2027.42/133445. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hamadani, Rashidaddin (1971). The Successors of Genghis Khan (PDF). Translated by Boyle, John Andrew. Columbia University Press. p. 129. ISBN 0-231-03351-6.

- Hamadani, p. 365

- Hope, p. 166

- Melville, Charles (2009-03-12), Fleet, Kate (ed.), The Cambridge History of Turkey (1 ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 51–101, doi:10.1017/chol9780521620932.004, ISBN 978-1-139-05596-3, retrieved 2020-04-27 Missing or empty

|title=(help);|chapter=ignored (help) - Fisher, p. 381

- Michaud, Yahia (Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies) (2002). Ibn Taymiyya, Textes Spirituels I-XVI", Chap. XI

- Hope, p. 168

- Roux, p. 432

- Yuan Chueh Chingjung chu-shih chi, ch. 34. p. 22.

- Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia by Thomas T. Allsen, p. 34.

- J. A. Boyle (1968). J. A. Boyle (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran (reprint, reissue, illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 417. ISBN 0-521-06936-X. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Jackson, p. 177.

- "The Trial of the Templars", Malcolm Barber, 2nd edition, page 22: "The aim was to link up with Ghazan, the Mongol Il-Khan of Persia, who had invited the Cypriots to participate in joint operations against the Mamluks".

- Roux, p. 410.

- Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West, p. 315.

- Demurger, p. 143.

- Demurger, p. 142 (French edition) "He was soon joined by King Hethum, whose forces seem to have included Hospitallers and Templars from the kingdom of Armenia, who participated to the rest of the campaign."

- Demurger, p. 142.

- Demurger, p. 142 "The Mongols pursued the retreating troops towards the south, but stopped at the level of Gaza"

- Runciman, p. 439.

- "Adh-Dhababi's Record of the Destruction of Damascus by the Mongols in 1299–1301", Note 18, p. 359.

- Demurger, p. 146.

- Schein, 1979, p. 810

- Demurger (p. 146, French edition): "After the Mamluk forces retreated south to Egypt, the main Mongol forces retreated north in February, Ghazan leaving his general Mulay to rule in Syria".

- Aigle, Denise. "The Mongol Invasions of Bilād al-Shām by Ghāzān Khān and Ibn Taymīyah's Three "Anti-Mongol" Fatwas" (PDF). Mamluk Studies Review. University of Chicago. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- Demurger, p. 147.

- Schein, 1979, p. 811.

- In "Le Royaume Armenien de Cilicie", pp. 74–75.

- Jean Richard, p. 481.

- Schein, p. 813.

- Encyclopædia Iranica article

- Demurger, "Jacques de Molay", p. 158.

- Demurger, p. 158.

- Nicolle, p. 80.

- Hamadani, p. 654

- The court of the Il-khans, 1290-1340 : the Barakat Trust Conference on Islamic Art and History, St. John's College, Oxford, Saturday, 28 May 1994. Raby, Julian., Fitzherbert, Teresa. Oxford: Oxford University Press for the Board of the Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford. 1996. p. 201. ISBN 0-19-728022-6. OCLC 37935458.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Hamadani, p. 661

- Arnold, Sir Thomas Walker (1896). "The Preaching of Islam". google.com.

- Amitai, see Section VI–Ghazan, Islam and Mongol Tradition– p. 9 and Section VII–Sufis and Shamans, p. 34.

- Foltz, p. 129.

- Hamadani, p. 642

- For numismatic information: Coins of Ghazan Archived 2008-02-01 at the Wayback Machine, Ilkhanid coin reading Archived 2008-02-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Maḥmūd Ghāzān." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009

- "Ghazan was a man of high culture. Besides his mother tongue Mongolian, he more or less spoke Arabic, Persian, Indian, Tibetan, Chinese, and "Frank", probably Latin." in Histoire de l'Empire Mongol, Jean-Paul Roux, p. 432.

- Enkhbold, Enerelt (2019). "The role of the ortoq in the Mongol Empire in forming business partnerships". Central Asian Survey. 38 (4): 531–547. doi:10.1080/02634937.2019.1652799.

- Enkhbold, Enerelt (2019). "The role of the ortoq in the Mongol Empire in forming business partnerships". Central Asian Survey. 38 (4): 531–547. doi:10.1080/02634937.2019.1652799.

- Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia by Thomas T. Allsen, p. 33.

- Mostaert and Cleaves Trois documents, p. 483.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ghazan. |

- Adh-Dhababi, Record of the Destruction of Damascus by the Mongols in 1299–1301 Translated by Joseph Somogyi. From: Ignace Goldziher Memorial Volume, Part 1, Online (English translation).

- Amitai, Reuven (1987). "Mongol Raids into Palestine (AD 1260 and 1300)". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society: 236–255.

- Barber, Malcolm (2001). The Trial of the Templars (2nd ed.). University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 978-0-521-67236-8.

- Encyclopædia Iranica, Article on Franco-Persian relations

- Fisher, William Bayne (1998), The Cambridge History of Iran, 5

- Foltz, Richard, Religions of the Silk Road, Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition, 2010 ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1

- Demurger, Alain (2007). Jacques de Molay (in French). Editions Payot&Rivages. ISBN 978-2-228-90235-9.

- Jackson, Peter (2005). The Mongols and the West: 1221–1410. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-36896-5.

- Hamadani, Rashidaddin (1998), Compendium of Chronicles, translated by Thackston, W.M, Harvard University, Dept. of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, OCLC 41120851

- Hope, Michael (2016), Power, politics, and tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran, ISBN 978-0-19-108107-1, OCLC 959277759

- Michaud, Yahia (Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies) (2002). Ibn Taymiyya, Textes Spirituels I-XVI (PDF) (in French). "Le Musulman", Oxford-Le Chebec.

- Nicolle, David (2001). The Crusades. Essential Histories. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-179-4.

- Richard, Jean (1996). Histoire des Croisades. Fayard. ISBN 2-213-59787-1.

- Runciman, Steven (1987 (first published in 1952–1954)). A history of the Crusades 3. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013705-7. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Schein, Sylvia (October 1979). "Gesta Dei per Mongolos 1300. The Genesis of a Non-Event". The English Historical Review. 94 (373): 805–819. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCIV.CCCLXXIII.805. JSTOR 565554.

- Roux, Jean-Paul (1993). Histoire de l'Empire Mongol (in French). Fayard. ISBN 2-213-03164-9.

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Baydu |

Ilkhan 1295–1304 |

Succeeded by Öljeitü |