Mongol invasions of Japan

The Mongol invasions of Japan (元寇, Genkō), which took place in 1274 and 1281, were major military efforts undertaken by Kublai Khan of the Yuan dynasty to conquer the Japanese archipelago after the submission of Korean kingdom of Goryeo to vassaldom. Ultimately a failure, the invasion attempts are of macro-historical importance because they set a limit on Mongol expansion and rank as nation-defining events in the history of Japan. The invasions are referred to in many works of fiction and are the earliest events for which the word kamikaze ("divine wind") is widely used, originating in reference to the two typhoons faced by the Mongol fleets.

| Mongol invasions of Japan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol invasion of East Asia and Kublai Khan's Campaigns | |||||||

Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Michiyasu Shiroishi Hida Nagamoto Mitsui Yasunaga Sashi Husashi Sashi Nao Sashi Tōdō Sashi Isamu Ishiji Kane Ishiji Jirō |

Mongol : Kublai Khan Holdon Liu Fuheng Atagai Hong Dagu Ala Temür Fan Wenhu Li T'ing Korea : King Wonjong King Chungnyeol Kim Bang-gyeong | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1274: 2,000–6,000[1] 1281: 40,000 (?) Reinforcements by Rokuhara Tandai: 60,000 (not yet arrived) |

1274: 28,000–30,000[2][3] 1281: 100,000 and 40,000[4] with 3,500 and 900 ships (respectively) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1274/1281: Minimal |

1274: 13,500[5] 1281: 100,000[6] 20,000–30,000 captured[7] | ||||||

The invasions were one of the earliest cases of gunpowder warfare outside of China. One of the most notable technological innovations during the war was the use of explosive, hand-thrown bombs.[8]

Background

After a series of Mongol invasions of Korea between 1231 and 1281, Goryeo signed a treaty in favor of the Mongols and became a vassal state. Kublai was declared Khagan of the Mongol Empire in 1260 (although this was not widely recognized by the Mongols in the west) and established his capital at Khanbaliq (within modern Beijing) in 1264.

Japan at the time was ruled by the Shikken (shogunate regents) of the Hōjō clan, who had intermarried with and wrested control from Minamoto no Yoriie, shōgun of the Kamakura shogunate, after his death in 1203. The inner circle of the Hōjō clan had become so preeminent that they no longer consulted the council of the shogunate (Hyōjō (評定)), the Imperial Court of Kyoto, or their gokenin vassals, and made their decisions at private meetings in their residences (yoriai (寄合)).

The Mongols also made attempts to subjugate the native peoples of Sakhalin—the Ainu, Orok, and Nivkh peoples—from 1260 to 1308.[9] However, it is doubtful if Mongol activities in Sakhalin were part of the effort to invade Japan.[10]

Contact

In 1266, Kublai Khan dispatched emissaries to Japan with a letter saying:

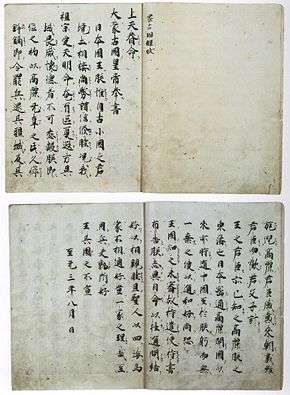

Cherished by the Mandate of Heaven, the Great Mongol emperors sends this letter to the emperor of Japan. The sovereigns of small countries, sharing borders with each other, have for a long time been concerned to communicate with each other and become friendly. Especially since my ancestor governed at heaven's commands, innumerable countries from afar disputed our power and slighted our virtue. Goryeo rendered thanks for my ceasefire and for restoring their land and people when I ascended the throne. Our relation is feudatory like a father and son. We think you already know this. Goryeo is my eastern tributary. Japan was allied with Goryeo and sometimes with China since the founding of your country; however, Japan has never dispatched ambassadors since my ascending the throne. We are afraid that the Kingdom is yet to know this. Hence we dispatched a mission with our letter particularly expressing our wishes. Enter into friendly relations with each other from now on. We think all countries belong to one family. How are we in the right, unless we comprehend this? Nobody would wish to resort to arms.[11]

Kublai essentially demanded that Japan become a vassal and send tribute under a threat of conflict. However, the emissaries returned empty-handed. The second set of emissaries were sent in 1268, returning empty-handed like the first. Both sets of emissaries met with the Chinzei Bugyō, or Defense Commissioner for the West, who passed on the message to Shikken, Hōjō Tokimune, Japan's ruler in Kamakura and to the Emperor of Japan in Kyoto. After discussing the letters with his inner circle, there was much debate, but the Shikken had his mind made up; he had the emissaries sent back with no answer. The Mongols continued to send demands, some through Korean emissaries and some through Mongol ambassadors on March 7, 1269; September 17, 1269; September 1271; and May 1272. However, each time, the bearers were not permitted to land in Kyushu.

The Imperial Court suggested compromise,[12] but really had little effect in the matter, due to political marginalization after the Jōkyū War. The uncompromising shogunate ordered all those who held fiefs in Kyūshū, the area closest to the Korean Peninsula and thus most likely to be attacked, to return to their lands and forces in Kyūshū moved west, further securing the most likely landing points. After acknowledging its importance, the Imperial Court led great prayer services to calm local residents, and much government business was put off to deal with this crisis.

First invasion preparations

The invasion fleet was scheduled to depart in the seventh lunar month of 1274 but was delayed for three months. Kublai planned for the fleet to first attack Tsushima Island and Iki Island before making landfall in Hakata Bay. The Japanese plan of defense was simply to contest them at every point with gokenin. Both Yuan and Japanese sources exaggerate the opposing side's numbers, with the History of Yuan putting the Japanese at 102,000, and the Japanese claiming they were outnumbered at least ten to one. In reality there are no reliable records of the size of Japanese forces but estimates put their total numbers at around 4,000 to 6,000. The Yuan invasion force composed of 15,000 Mongol, Han Chinese, and Jurchen soldiers, and 6,000 to 8,000 Korean troops as well as 7,000 Korean sailors.[2][3]

First invasion (1274)

_-_Tokyo_National_Museum.jpg)

The Yuan invasion force set off from Korea on 2 November 1274. Two days later they landed on Komodahama beach on Tsushima Island. Sō Sukekuni, the governor of Tsushima, led a cavalry unit of 80 to defend the island, but was overwhelmed and killed. The Yuan fleet departed Tsushima on 13 November and attacked Iki Island. Like Sukekuni, Taira Kageetaka, the governor of Iki, gave a spirited defense before falling back to his castle by nightfall. The next morning, Yuan forces had surrounded the castle. Kagetaka made a final failed sortie before committing suicide with his family.[13]

The Yuan fleet crossed the sea and land in Hakata Bay on 19 November, a short distance from Dazaifu, the ancient administrative capital of Kyūshū. The following day brought the Battle of Bun'ei (文永の役), also known as the "First Battle of Hakata Bay". Conlan argues that the History of Yuan's account of the battle suggests that both the Japanese and Yuan forces were of similar size. Conlan estimated that both armies numbered around 3,000 each (not including the Yuan sailors) during this battle.[14] The Japanese forces inexperienced with non-Japanese tactics found the Mongol army perplexing. The Yuan forces disembarked and advanced in a dense body protected by a screen of shields. They wielded their polearms in a tightly packed fashion with no space between them. As they advanced they also threw paper and iron casing bombs on occasion, frightening the Japanese horses and making them uncontrollable in battle. When the grandson of a Japanese commander shot an arrow to announce the beginning of battle, the Mongols burst out laughing. By nightfall, the Japanese had been driven several kilometres inland.[15]

The commanding general kept his position on high ground, and directed the various detachments as need be with signals from hand-drums. But whenever the (Mongol) soldiers took to flight, they sent iron bomb-shells (tetsuho) flying against us, which made our side dizzy and confused. Our soldiers were frightened out of their wits by the thundering explosions; their eyes were blinded, their ears deafened, so that they could hardly distinguish east from west. According to our manner of fighting, we must first call out by name someone from the enemy ranks, and then attack in single combat. But they (the Mongols) took no notice at all of such conventions; they rushed forward all together in a mass, grappling with any individuals they could catch and killing them.[16]

— Hachiman Gudoukun

Despite the invasion's success in pushing back Japanese forces, a senior Yuan commander, Liu Fuxiang, had been seriously injured in battle. The Mongol and Korean ship captains were also concerned with their small numbers and the possibility of facing a larger Japanese army, so they decided to retreat and set sail for Korea. For the ships at that time the navigation to north, i.e. from Hakata to Korea's south-eastern shores, was risky, if not in daytime and under south wind. However, they pressed ahead the retreating action at night and encountered severe storms. Some accounts offer casualty reports that suggest 200 ships were lost. Of the 30,000 strong invasion force, 13,500 did not return.[5]

A story widely known in Japan is that back in Kamakura, Tokimune was overcome with fear when the invasion finally came, and wanting to overcome his cowardice, he asked Mugaku Sogen, his Zen master also known as Bukko, for advice. Bukko replied he had to sit in meditation to find the source of his cowardice in himself. Tokimune went to Bukko and said, "Finally there is the greatest happening of my life." Bukko asked, "How do you plan to face it?" Tokimune screamed, "Katsu!" ("Victory!") as if he wanted to scare all the enemies in front of him. Bukko responded with satisfaction, "It is true that the son of a lion roars as a lion!"[17] Since that time, Tokimune was instrumental in spreading Zen and Bushido in Japan among the samurai.

Preparations between the first and second invasion

After the invasion of 1274, the shogunate made efforts to defend against a second invasion, which they thought was sure to come. In addition to better organizing the samurai of Kyūshū, they ordered the construction of forts and a large stone wall (石塁, Sekirui), and other defensive structures at many potential landing points, including Hakata Bay, where a two-meter-high (6.6 ft) high wall was constructed in 1276.[18]

Religious services increased and the Hakozaki Shrine, having been destroyed by the Yuan forces, was rebuilt. A coastal watch was instituted and rewards were given to some 120 valiant samurai. There was even a plan for a raid on Goryeo (modern-day Korea) to be carried out by Shōni Tsunesuke, a general from Kyūshū, though this was never executed.

Kublai Khan sent five Yuan emissaries in September 1275 to Kyūshū, who refused to leave without a reply. Tokimune responded by having them sent to Kamakura and then beheading them.[19] The graves of those five executed Yuan emissaries exist to this day at Jōryū-ji, in Fujisawa, Kanagawa, near the Tatsunokuchi Execution Place in Kamakura.[20] Five more Yuan emissaries were sent on July 29, 1279, in the same manner, and again beheaded, this time in Hakata.

In the autumn of 1280, Kublai held a conference at his summer palaces to discuss plans for a second invasion of Japan. The major difference between the first and second invasion was that the Yuan dynasty had finished conquering the Song dynasty in 1279 and was able to launch a two-pronged attack. The invading force was drawn from a number of sources including criminals with commuted death sentence and even those in mourning for their parents (a serious affair in contemporary China). More than 1,000 ships were requisitioned for the invasion: 600 from Southern China, 900 from Korea. Reportedly 40,000 troops were amassed in Korea and 100,000 in Southern China. These numbers are likely an exaggeration but the addition of Southern Chinese resources probably meant the second invasion force was still several times larger than the first invasion. Nothing is known about the size of the Japanese forces.[4]

Second invasion (1281)

Orders for the second invasion came in the first lunar month of 1281. Two fleets were prepared, a force of 900 ships in Korea and 3,500 ships in Southern China with a combined force of 142,000 soldiers and sailors.[14] The Mongol general Arakhan was named supreme commander of the operation and was to travel with the Southern Route fleet, which was under the command of Fan Wenhu, and delayed due to supply difficulties.[21] The Eastern Route army set sail first from Korea on 22 May and attacked Tsushima on 9 June and Iki Island on 14 June. According to the History of Yuan, the Japanese commander Shoni Suketoki and Ryuzoji Suetoki led forces in the tens of thousands against the invasion force. The expeditionary forces discharged their firearms and the Japanese were routed with Suketoki killed in the process. More than 300 islanders were killed. The soldiers sought out the children and killed them as well.[22]

The Eastern Route army was supposed to wait for the Southern Route army at Iki but disobeyed orders and set out to invade mainland Japan by themselves. They departed on 23 June, a full week ahead of the expected arrival of the Southern Route army on 2 July. The Eastern Route army split their forces in half to simultaneously attack Hakata Bay and Nagato Province. Three hundred ships attacked Nagato on 25 June but were driven off and forced to return to Iki. Meanwhile, the rest of the Eastern Route army attacked Hakata Bay, which was heavily fortified with a defensive wall. Some Mongol ships came ashore but were driven off by volleys of arrows from the defensive wall. Unable to land, the Mongol invasion force occupied the islands of Shiga and Noko from which they planned to launch raids against Hakata. Instead the Japanese launched raids against them at night on board small ships. The Hachiman Gudokun credit Kusano Jiro with boarding a Mongol ship, setting fire to it, and taking 21 heads. The next day, Kawano Michiari led a daytime raid with just two boats. His uncle Michitoki was immediately killed by an arrow and Michiari was wounded both in the shoulder and the left arm. However upon boarding the enemy ship, he slew a large Mongol warrior, for which he was made a hero and richly rewarded. The Mongols were eventually driven from Shiga island and withdrew to Iki on 30 June. The Japanese defense of Hakata Bay is known as the Battle of Kōan. On 16 July, fighting commenced between the Japanese and Mongols at Iki Island, resulting in Mongol withdrawal to Hirado Island.[23]

After the Southern Route fleet convened with the Northern Route fleet, the two fleets took some time rearranging themselves before advancing on Taka island. On 12 August, the Japanese repeated their small raids on the invasion fleet. The Mongols responded by fastening their ships together with chains and planks to provide defensive platforms. There are no accounts of the raids from the Japanese side in this incident unlike at the defense of Hakata Bay. According to the History of Yuan, the Japanese ships were small and were all beaten off. It was at this point that a great typhoon, known in Japanese as kamikaze, struck the fleet at anchor and devastated it. Sensing the oncoming typhoon, Korean and south Chinese mariners retreated and unsuccessfully docked in Imari Bay where they were destroyed by the storm.[24] Thousands of soldiers were left drifting on pieces of wood or washed ashore. The Japanese defenders killed all they found except for the Southern Chinese, who they felt had been coerced into joining the attack on Japan. According to a Chinese survivor, after the typhoon, Commander Fan Wenhu picked the best remaining ships and sailed away, leaving more than 100,000 troops to die. After being stranded for three days on Taka island, the Japanese attacked, capturing tens of thousands. They were moved to Hakata where the Japanese killed all the Mongols, Koreans, and Northern Chinese. The Southern Chinese were spared but made slaves. According to a Korean source, of the 26,989 Koreans who set out with the Eastern Route fleet, 7,592 did not return.[6]

Size of the invasion

Many modern historians believe the figures for the invasion force to be exaggerated, as was common in medieval chronicles. Professor Thomas Conlan states that they were likely exaggerated by an order of magnitude (implying 14,000 soldiers and sailors), expressing skepticism that a medieval kingdom managed an invasion on the scale of D-Day during World War II across over ten times the distance, and questions if even 10,000 soldiers attacked Japan in 1281.[14] Morris Rossabi states that Conlan was correct in his assertion that the invasion force was much smaller than traditionally believed, but argues that the expenditures lavished on the mission confirm that the fighting force was sizable and much larger than 10,000 soldiers and 4,000 sailors. He puts forward the alternative figure of 70,000 soldiers and sailors, half of what is spoken of in the Yuanshi and later Japanese claims.[25] Turnbull thinks that 140,000+ is an exaggeration, but does not offer his own precise estimate for the size of the army. Rather, he only states that given the contributions of the Southern Song, the second invasion should have been around three times larger than the first. As he earlier listed the common figure of 23,000 for the first invasion uncritically, unlike the estimate of 140,000+ for the second, that would imply an invasion force of ~70,000, on par with Rossabbi's estimate.[26]

Military significance

Kublai Khan's invasions of Japan were the first of only three instances when the samurai fought foreign troops rather than amongst themselves; the others being Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98) and the Japanese invasion of Ryukyu (1609). The invasions exposed the Japanese to an alien fighting style which, lacking the single combat that characterized traditional samurai combat, they saw as inferior. The Mongol method of advances and withdrawals based on signal sounds from bells, drums and war cries was also unknown in Japan at that time, as was the technique of shooting arrows en masse into the air rather than long-ranged one-on-one combat.

The Mongol invasions of Japan facilitated a change in the designs of Japanese swords. Thin tachi and chokuto style blades were often unable to cut through the boiled leather armor of the Mongols, with the blades often chipping or breaking off.[27] Tachi blades were shortened and thickened, with the katana eventually being introduced as a result.

The Mongols and the Ashikaga shogunate of Japan made peace in the late 14th century during the reign of Toghon Temür, the last Yuan emperor in Khanbaliq. Long before the peace agreement, there was stable trade in East Asia under the dominance of the Mongols and Japan.

As a consequence of the destruction of the Mongol fleets, Japan's independence was guaranteed. Simultaneously, a power struggle within Japan led to the dominance of military governments and diminishing Imperial power.[28]

Bombs and cannons

The Mongol invasions are an early example of gunpowder warfare. One of the most notable technological innovations during the war was the use of explosive bombs.[8] The bombs are known in Chinese as "thunder crash bombs" and were fired from catapults, inflicting damage on enemy soldiers. An illustration of a bomb is depicted in the Japanese Mongol Invasion scrolls, but Thomas Conlan has shown that the illustration of the projectiles was added to the scrolls in the eighteenth century and should not be considered to be an eyewitness representation of their use.[29] Archaeological evidence of the use of gunpowder was finally confirmed when multiple shells of the explosive bombs were discovered in an underwater shipwreck off the shore of Japan by the Kyushu Okinawa Society for Underwater Archaeology. X-rays by Japanese scientists of the excavated shells provided proof that they contained gunpowder.[30]

The Yuan forces may have also used cannons during the invasion. The Taiheiki mentions a weapon shaped like a bell that made a noise like thunder-clap and shot out thousands of iron balls.[31][32]

Cultural influence

The Zen Buddhism of Hojo Tokimune and his Zen master Bukko gained credibility beyond national boundaries, and the first mass followings of Zen teachings among samurai began to flourish.

The failed invasions also mark the first use of the word kamikaze ("Divine Wind"). The fact that the typhoon that helped Japan defeat the Mongol Navy in the first invasion occurred in late November, well after the normal Pacific typhoon season (May to October), perpetuated the Japanese belief that they would never be defeated or successfully invaded, which remained an important aspect of Japanese foreign policy until the very end of World War II. The failed invasions also demonstrated a weakness of the Mongols – the inability to mount naval invasions successfully[33] (see also Mongol invasions of Vietnam and Java) After the death of Kublai, his successor, Temür Khan, unsuccessfully demanded the submission of Japan in 1295.

Gallery

Japanese attack ships

Japanese attack ships Mongol soldiers, second version

Mongol soldiers, second version Mongol ships, second version

Mongol ships, second version

See also

- Genkō Bōrui

- Korea under Yuan rule

- Second Mongol invasion of Hungary (1285–86)

- Battle of Khalkin Gol - Failed Japanese attempt to invade Mongolia in 1939

Notes

- Conlan, p. 261-263; cites a variety of estimate from various Japanese historians as well as the author's own.

- Twitchett 1994, p. 437-442.

- Turnbull 2010, p. 32.

- Turnbull 2010, p. 55-57.

- Turnbull 2010, p. 49-50.

- Turnbull 2010, p. 69-76.

- 『元史』巻二百八 列傳第九十五 外夷一 日本國「(至元十八年)官軍六月入海、七月至平壷島(平戸島)、移五龍山(鷹島?)、八月一日、風破舟、五日、文虎等諸將各自擇堅好船乘之、棄士卒十餘萬于山下、衆議推張百戸者爲主帥、號之曰張總管、聽其約束、方伐木作舟欲還、七日日本人來戰、盡死、餘二三萬爲其虜去、九日、至八角島、盡殺蒙古、高麗、漢人、謂新附軍爲唐人、不殺而奴之、閶輩是也、蓋行省官議事不相下、故皆棄軍歸、久之、莫靑與呉萬五者亦逃還、十萬之衆得還者三人耳。」

- Stephen Turnbull (19 February 2013). The Mongol Invasions of Japan 1274 and 1281. Osprey Publishing. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-4728-0045-9. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- The conquest of Ainu lands: ecology and culture in Japanese expansion, 1590–1800 By Brett L. Walker, p.133

- Nakamura, Kazuyuki (2010). "Kita kara no mōko shūrai wo meguru shōmondai" 「北からの蒙古襲来」をめぐる諸問題 [Several questions around "the Mongol attack from the north"]. In Kikuchi, Toshihiko (ed.). Hokutō Ajia no rekishi to bunka 北東アジアの歴史と文化 [A history and cultures of Northeast Asia] (in Japanese). Hokkaido University Press. p. 428. ISBN 9784832967342.

- Original text in Chinese: 上天眷命大蒙古國皇帝奉書日本國王朕惟自古小國之君境土相接尚務講信修睦況我祖宗受天明命奄有區夏遐方異域畏威懷德者不可悉數朕即位之初以高麗無辜之民久瘁鋒鏑即令罷兵還其疆域反其旄倪高麗君臣感戴來朝義雖君臣歡若父子計王之君臣亦已知之高麗朕之東藩也日本密邇高麗開國以來亦時通中國至於朕躬而無一乘之使以通和好尚恐王國知之未審故特遣使持書布告朕志冀自今以往通問結好以相親睦且聖人以四海為家不相通好豈一家之理哉以至用兵夫孰所好王其圖之不宣至元三年八月日

- Smith, Bradley Japan: A History in Art 1979 p.107

- Turnbull 2010, p. 37.

- Conlan, p. 264

- Turnbull 2010, p. 49.

- Needham 1986, p. 178.

- Jonathan Clements (7 February 2013). A Brief History of the Samurai. Little, Brown Book Group. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-4721-0772-5.

- 福岡市教育委員会 (1969). "福岡市今津元寇防塁発掘調査概報". Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan. Retrieved 2016-09-02.

- Reed, Edward J. (1881). Japan: its History, Traditions, and Religions, p. 291., p. 291, at Google Books

- "常立寺". www.kamakura-burabura.com. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Winters, Harold et al. (2001). Battling the Elements, p. 14., p. 14, at Google Books

- Turnbull 2010, p. 58.

- Turnbull 2010, p. 69.

- Emanuel, Kerry; Emanuel, Professor Department of Earth Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences Program in Atmospheres Oceans and Climate Kerry (1 September 2005). Divine Wind: The History and Science of Hurricanes. Oxford University Press, USA. Retrieved 30 April 2018 – via Internet Archive.

mongol invasion of japan.

- Rossabi, Morris. "Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times." 1988. Page xiii.

- Turbull 2013, p. 57

- Satō, Kanzan. Kodansha International. 1983. Page 104

- Davis, Paul K. (2001). 100 decisive battles: from ancient times to the present, p. 146., p. 146, at Google Books

- Conlan, Thomas. "Myth, Memory and the Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions of Japan". in Lillehoj, Elizabeth ed. Archaism and Antiquarianism in Korean and Japanese Art (Chicago: Center for the Art of East Asia, University of Chicago and Art Media Resources, 2013), pp. 54-73.

- Delgado, James (February 2003). "Relics of the Kamikaze". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 56 (1). Archived from the original on 2013-12-29.

- Needham 1986, p. 295.

- Purton 2010, p. 109.

- "The Mongols in World History | Asia Topics in World History". afe.easia.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

References

- Satō, Kanzan (1983) The Japanese Sword. Kodansha International. ISBN 9780870115622

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3.

- Davis, Paul K. (1999). 100 Decisive Battles: From Ancient Times to the Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514366-9; OCLC 0195143663

- Purton, Peter (2010), A History of the Late Medieval Siege, 1200–1500, Boydell Press, ISBN 978-1-84383-449-6

- Reed, Edward J. (1880). Japan: its History, Traditions, and Religions. London: J. Murray. OCLC 1309476

- Sansom, George. (1958). A History of Japan to 1334, Stanford University Press, 1958.

- Turnbull, Stephen R. (2003). Genghis Khan and the Mongol Conquests, 1190–1400. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-96862-1

Turnbull, Stephen (2010), The Mongol Invasions of Japan 1274 and 1281, Osprey

- Winters, Harold A.; Gerald E. Galloway Jr.; William J. Reynolds and David W. Rhyne. (2001). Battling the Elements: Weather and Terrain in the Conduct of War. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins Press. ISBN 9780801866487; OCLC 492683854

Further reading

- Conlan, Thomas. (2001). In Little Need of Divine Intervention, Cornell University Press, 2001 – includes a black-and-white reproduction of the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba, as well as translations of relevant Kamakura-era documents and an essay by Prof. Conlan concerning the Invasions (in which he argues that the Japanese were better placed to withstand the Mongols than traditionally given credit for). The essay is available in pdf form at this link.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mongol invasions of Japan. |

- Mongol Invasion Scrolls Online - an interactive viewer detailing the Moko Shurai Ekotoba, developed by Professor Thomas Conlan

- Mongol Invasions of Japan - selection of photos by Louis Chor

- Mongol Invasions Painting Scrolls - more illustrations from the Moko Shurai Ekotoba

- Goryeosa 高麗史 full text from the National Diet Library of Japan

- Sasaki, Randall James (2008), The origin of the lost fleet of the Mongol Empire (PDF) (An MA thesis discussing the construction of the invasion fleet, and the discovery of its remains by modern underwater archaeologists)

- Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan, Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties

- https://books.google.com/books?id=vFS2iT8QjqEC&pg=PA104&lpg=PA104&dq=japanese+swords+mongol+armor&source=bl&ots=-6wb5pPl1J&sig=JNDNU-JdZEaNBSHCZ1rFV2Sn7RM&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiwsJa7oLvSAhXFQiYKHerEC9Y4ChDoAQg1MAU#v=onepage&q=japanese%20swords%20mongol%20armor&f=false