Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, often just the Dutch War (French: Guerre de Hollande; Dutch: Hollandse Oorlog), was a conflict that lasted from 1672 to 1678 between the Dutch Republic and France, each supported by allies. France had the support of England and Sweden, while the Dutch were supported by Spain, the Holy Roman Empire and Denmark.

The war began in May 1672 when France invaded the Netherlands and nearly overran it, an event still referred to as het Rampjaar or 'Disaster Year'.[3] By late July, the Dutch position had stabilised, with support from Emperor Leopold, Brandenburg-Prussia and Spain; this was formalised in the August 1673 Treaty of the Hague, joined by Denmark in January 1674.

Faced by a financial crisis, Sweden agreed to remain neutral in return for French subsidies, but became involved in the 1675–1679 Scanian War with its regional rivals Denmark and Brandenburg. On balance, the cost of funding the Swedish army made its support largely negative for France.

The period of English participation as an ally of France is also known as the Third Anglo-Dutch War; the alliance was always unpopular and domestic opposition led to its exit in the February 1674 Treaty of Westminster.[4] In November 1677, William of Orange married his cousin Mary, niece to Charles II of England and England agreed a defensive alliance with the Dutch in March 1678.

Under the Peace of Nijmegen, France returned Charleroi to Spain. In return, it received the Franche-Comté and cities in Flanders and Hainaut, essentially establishing modern France's northern border. However, the rivalry between Louis and William would persist and the latter would lead further anti-French coalitions in the 1688–1697 Nine Years' War and 1701–1714 War of the Spanish Succession.

Origins

As part of a general policy of opposition to Habsburg power in Europe, France backed the Dutch Republic during the 1568 to 1648 Eighty Years War against Spain. The 1648 Peace of Münster confirmed Dutch independence and permanently closed the Scheldt estuary, benefiting Amsterdam by eliminating its rival, Antwerp. Preserving this monopoly was a Dutch priority, but this increasingly clashed with French aims in the Spanish Netherlands, which included reopening Antwerp.[5]

William II of Orange's death in 1650 led to the First Stadtholderless Period, with political control vested in the urban patricians or Regenten. This maximised the influence of the States of Holland and Amsterdam, the power base of Johan de Witt, Grand Pensionary from 1653 to 1672. He viewed Louis XIV of France as crucial to ensure Dutch economic power, but also against his domestic Orangist opponents.[6]

Although France and the Republic concluded a military assistance treaty in 1662, opposition from the province of Holland against a division of the Spanish Netherlands convinced Louis achieving his aims required military action. The Dutch received limited French support during the 1665-1667 Second Anglo-Dutch War but increasingly preferred a weak Spain as a neighbour to a strong France.[lower-alpha 1] Shortly after talks to end the Anglo-Dutch War began in May 1667, Louis launched the War of Devolution, rapidly occupying most of the Spanish Netherlands and Franche-Comté.[7]

In July, the Treaty of Breda ended the Anglo-Dutch War, leading to talks between the Dutch and Charles II of England on a common diplomatic front against France. This was supported by Spain and Emperor Leopold, who was also concerned by French expansion. After his first suggestion of an Anglo-French alliance was rejected by Louis, Charles entered the 1668 Triple Alliance, between England, the Republic and Sweden. After the Alliance mediated between France and Spain, Louis relinquished many of his gains in the 1668 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle.[8]

While Breda and Aix-la-Chapelle were seen as Dutch diplomatic triumphs, they also presented significant dangers; De Witt himself was well aware of these, but failed to convince his colleagues. Louis considered the January 1668 Partition Treaty with Leopold confirmation of his right to the Spanish Netherlands, a point reinforced by Aix-la-Chapelle, despite his concessions. He no longer saw the need to negotiate, and decided their acquisition was best achieved by first defeating the Republic.[9]

The Dutch also over-stated their own power; defeat at Lowestoft in 1665 exposed the shortcomings of their navy and the federal command system, while the successful Medway raid was largely due to English financial weakness. In 1667, the Dutch navy was at the height of its power, an advantage rapidly eroded by English and French naval expansion. The Anglo-Dutch War had been primarily fought at sea, masking the poor state of their army and forts, deliberately neglected since they were viewed as bolstering the power of the Prince of Orange.[10]

In preparation for an attack on the Republic, Louis embarked on a series of diplomatic initiatives, the first being the 1670 Secret Treaty of Dover, an Anglo-French alliance against the Dutch.[11] It contained secret clauses not revealed until 1771, including the payment to Charles of £230,000 per year for providing a British brigade of 6,000.[12] Agreements with the Bishopric of Münster and Electorate of Cologne allowed French forces to bypass the Spanish Netherlands, by attacking via the Bishopric of Liège, then a dependency of Cologne (see Map).[13] Preparations were completed in April 1672, when Charles XI of Sweden accepted French subsidies in return for invading areas of Pomerania claimed by Brandenburg-Prussia.[14]

Preparations

French armies of the period held significant advantages over their opponents; an undivided command, talented generals like Turenne, Condé and Luxembourg and vastly superior logistics. Reforms introduced by Louvois, Louis' Secretary of War, helped maintain large field armies that could be mobilised much quicker. This allowed the French to mount offensives in early spring before their opponents were ready, seize their objectives and then assume a defensive posture.[15]

The retention of border towns like Charleroi and Tournai allowed Louvois to pre-position supply dumps, stretching from the French border to Neuss in the Rhineland. Of 180,000 men mobilised, 120,000 were allocated to attacks on the Republic, split into two main groups; one at Charleroi, under Turenne, the other near Sedan, commanded by Condé. After marching through the Bishopric of Liège, they would join near Maastricht, then occupy the Duchy of Cleves, a possession of Frederick William of Brandenburg. Finally, 30,000 German mercenaries, paid by Münster and Cologne and led by Luxembourg, would attack from the east.[16]

An additional element was an English landing in the Spanish Netherlands; Louis agreed to give Charles key coastal positions, including Walcheren, Cadzand and Sluys, which controlled access to Antwerp.[17] Whether he intended to keep this promise is doubtful and in any case, it ceased to be viable when the Dutch retained control of the sea at Solebay in June.[18]

%2C_prins_van_Oranje._Stadhouder%2C_sedert_1689_tevens_koning_van_Engeland_Rijksmuseum_SK-A-1228.jpeg)

The French demonstrated their new tactics in over-running the Duchy of Lorraine in mid 1670, while the Dutch were given accurate information on their plans as early as February 1671. These were confirmed by Condé in November and again in January 1672, Dutch regent de Groot describing him as 'one of our best friends.'[19] The United Provinces were ill-prepared for a land campaign against France. Since 1648, the defence budgets had been largely invested in the fleet. There were numerous fortresses but these had been completely neglected. Much of the Dutch States Army were based in the three southern fortresses of Breda, 's-Hertogenbosch and Maastricht; in November 1671, the Council of State reported these as being short of supplies and money, with many fortifications barely defendable.[20] Many units were far below strength; on 12 June, one officer reported his official garrison of eighteen companies only had enough men for four.[lower-alpha 2] [21]

With Prince William now of age, his supporters refused to approve additional military spending unless he was appointed Captain-General, a move opposed by de Witt. Aware of internal English opposition to the Anglo-French alliance, the Orangists relied on the provisions of the Triple Alliance requiring England and the Republic to support each other, if attacked by Spain or France. The English Parliament shared this assumption; in early 1671, they approved funding for the fleet, specifically to fulfil its obligations under the alliance.[22] The true danger only became obvious on 23 March, when the Royal Navy attacked a Dutch merchant convoy in the Channel; a similar incident had occurred in 1664.[23]

In February 1672, de Witt compromised by appointing William as Captain-General for a year. Budgets were approved and contracts issued to increase the army to over 80,000 but these men would take months to assemble. Negotiations with Frederick William to reinforce Cleves with 30,000 men were delayed by his demands for Dutch-held fortresses on the Rhine, including Rheinberg and Wesel. By the time they reached agreement on 6 May, he was occupied with a French-backed Swedish invasion of Pomerania.[24] Though assembling an army in the west, he would not engage the French in 1672.

The garrison of Maastricht was increased to 11,000, in the hope they could delay the French long enough to strengthen the eastern border; the cities provided 12,000 men from their civil militia, with 70,000 peasants conscripted to build earthworks along the IJssel river. These were unfinished when France declared war on 6 April, followed by England on 7 April, using a manufactured diplomatic incident known as the 'Merlin' affair.[25] Münster and Cologne entered the war on 18 May.

French Offensive: 1672

The French breach the Rhine positions

The French offensive began on 4 May, Condé marching from Sedan.[26] Louis, arriving in Charleroi, inspected the formed up troops of Turenne on 5 May 1672, in one of the most magnificent displays of military power in the seventeenth century.[26] On 11 May, Turenne too marched to the north with fifty thousand men, accompanied by Louis personally.[26] Both forces united at Visé on 17 May, just south of Maastricht. Louis desired to besiege the fortress and Condé agreed but Turenne managed to convince the king that it would be folly to allow the Dutch time to reinforce.[26] Avoiding a direct assault on Maastricht, the French first occupied the forts of Tongeren, Maaseik and Valkenburg.[27]

.jpg)

Leaving a force of ten thousand behind, the French army advanced along the Rhine, supported by troops from Münster and the Electorate of Cologne. The fortresses intended to block a French Rhine crossing were simultaneously besieged from 1 June onwards and taken in quick succession because they were still severely undermanned.[28] The French captured Rheinberg and Orsoy almost without meeting any resistance.[28] Burick, facing thirty thousand troops, was next.[28] Wesel was the most important fortress but the wives of the 1200 soldiers, threatening to literally butcher the commanders, forced a capitulation on 5 June.[28] Rees, with a garrison of just four hundred and attacked by twelve thousand men, was the last to fall, on 9 June.[28] At that moment, the bulk of the French army had already started to cross the Rhine at Emmerich am Rhein. Grand Pensionary De Witt was deeply shocked by the news of the catastrophe and concluded that "the fatherland is now lost".[29]

Whereas the situation on land had become critical for the Dutch, the events at sea were much more favourable to them. On 7 June, Dutch Lieutenant-Admiral Michiel de Ruyter boldly attacked the Anglo-French fleet resupplying on the English coast at Southwold. The Battle of Solebay was a tactical draw but a strategic Dutch victory, as it prevented an attempted Anglo-French blockade,[30] which would have starved the large Dutch urban population. During the battle the French squadron under d'Estrées failed to properly coordinate its actions with the English main force and ended up fighting a separate battle with Zealandic Lieutenant-Admiral Banckert, which led to mutual suspicions and recriminations.

The IJssel Line is outflanked

.jpg)

In early June, the Dutch headquarters at Arnhem prepared itself for a French onslaught on the IJssel Line. Only twenty thousand troops could be assembled to block a crossing and a dry spring meant that the river could be forded at many points. Nevertheless, there seemed to be no alternative but to make a last stand at the IJssel. However, should the enemy outflank this river by crossing the Lower Rhine into the Betuwe, the field army would fall back to the west to prevent being surrounded and quickly annihilated.[31] The commander of Fort Schenkenschanz protecting the Lower Rhine abandoned his position. When he arrived at Arnhem with his troops, immediately a force of two thousand horse and foot under Field Marshal Paulus Wirtz was sent out to cover the Betuwe. At arrival they intercepted French cavalry crossing at a ford pointed out to them by a farmer. A bloody encounter fight followed but in this Battle of Tolhuis on 12 June, the Dutch cavalry was eventually overwhelmed by French reinforcements. Louis personally observed the battle from the Elterberg.[32] Condé was shot through the wrist. This battle was in France celebrated as a major victory and paintings of the Passage du Rhin have this crossing as their subject,[33] not the earlier one at Emmerich.

Captain-General William Henry now wanted the entire field army to fall back on Utrecht. However, in 1666 the provinces had regained full sovereignty of their forces. Overijssel and Guelders in June 1672 withdrew their troops from the confederate army. The French army made little effort to cut off the escape route of the Dutch field army. Turenne recrossed the Lower Rhine to attack Arnhem, while part of his army moved to the Waal towards Fort Knodsenburg at Nijmegen.[34] Louis wanted to besiege Doesburg first, on the east side of the IJssel, taking it on 21 June.[35] The king delayed the capture somewhat to allow his brother Philippe I, Duke of Orléans to take Zutphen some days earlier.[36] On his right flank, the armies of Münster and Cologne, reinforced by a French corps under de Luxembourg, advanced to the north along the river, after having taken Grol on 10 June and Bredevoort on 18 June.[37] The IJssel cities panicked. Deventer seceded from the Republic and again joined the Holy Roman Empire on 25 June.[35] Then the province of Overijssel surrendered as a whole to the bishop of Münster, Bernard von Galen. Von Galen's troops plundered towns on the west side of the IJssel, such as Hattem, Elburg and Harderwijk, on 21 June.[35] Louis ordered de Luxembourg to kick them out again,[36] as he wanted to make the duchy of Guelders a French possession.[38] Annoyed, Von Galen announced to advance to the north of the Republic and invited de Luxembourg to follow him by wading through the IJssel, as no pontoon bridge was available. Exasperated, de Luxembourg got permission from Louis to withhold his corps and the army of Cologne from the Münsterite forces.

From that point onwards, Von Galen would wage a largely separate campaign. He started to besiege Coevorden on 20 June. Von Galen, nicknamed "Bomb Berend", was an expert on artillery ammunition and had devised the first practical incendiary shell or carcass. With such fire shot he intimidated the garrison of Coevorden into a quick surrender on 1 July. He was advised by his subcommanders to subsequently plunder the hardly defended Friesland and use vessels captured there to isolate Groningen, the largest city in the north. Alternatively, he could take Delfzijl, allowing a landing by an English expeditionary force. But the bishop feared that the Protestant British would make common cause with the Calvinist Groningers and expected that his siege mortars would force a fast capitulation, starting the Siege of Groningen on 21 July.

Peace negotiations

_-_The_Surrender_of_Utrecht.jpg)

On 14 June, William arrived with the remnants of the field army, some eight thousand men, at Utrecht.[39] The common citizens had taken over the city gates and refused him entrance.[40] In talks with the official city council, William had to admit that he had no intention to defend the city but would retreat behind the Holland Water Line, a series of inundations protecting the core province of Holland. Eventually, the council of Utrecht literally delivered the keys of the gates to Henri Louis d'Aloigny, Marquis de Rochefort, to avoid plundering. On 18 June, William withdrew his forces. The flooding was not ready yet, only having been ordered on 8 June, and the countryside of Holland was basically defenceless against the French.[34] On 19 June, the French took the fortress of Naarden close to Amsterdam.[41]

In a defeatist mood a divided States of Holland – Amsterdam was more pugnacious – sent a delegation to de Louvois in Zeist to ask for peace terms, headed by Pieter de Groot.[42] The French king was offered the Generality Lands and ten million guilders. Compared to the eventual outcome of the war, these conditions were very favourable to France. It would have made territorial gains not equalled until 1810. The Generality Lands included the fortresses of Breda, 's-Hertogenbosch and Maastricht. Their possession would have ensured the conquest of the Spanish Netherlands and the remaining Republic would have been little more than a French satellite state. De Louvois, rather bemused that the Estates had not capitulated but still considered some damage control possible, demanded far harsher conditions though.[43] The Dutch were given the choice of surrendering their southern fortresses, permitting religious freedom for Catholics and a payment of six million guilders, or France and Münster retaining their existing gains – thus the loss of Overijssel, Guelders and Utrecht – and a single payment of sixteen million livres. Louis knew perfectly well that the delegation did not have the mandate to agree such terms and would have to return for new instructions. However, he also did not continue his advance to the west.[34]

Several explanations have been given for this policy. The French were rather overwhelmed by their success. They had within a month captured three dozen fortresses.[44] This strained their organisational and logistical capacities. All these strongholds had to be garrisoned and supplied.[44] An intrusion into Holland proper seemed meaningless to them, unless Amsterdam could be besieged. This city would be a very problematic target. It had a population of 200,000 and could raise a large civil militia, reinforced by thousands of sailors. As the city had recently expanded, its fortifications were the best maintained in the Republic. Their normal armament of three hundred pieces was being enlarged by the militia hauling the reserve ordnance of the Admiralty of Amsterdam upon the ramparts which began to bristle with thousands of cannon. The low-lying surrounding terrain, below sea level, was easily flooded, making a traditional attack via trenches impractical. The battle fleet could support the fortifications from the IJ and Zuyderzee with gun fire, meanwhile ensuring a constant resupply of the food and ammunition stocks. A deeper problem was that Amsterdam was the world's main financial centre. The promissory notes with which many of the French military and the contractors had been paid, were covered by the gold and silver reserves of the Amsterdam banks. Their loss would mean the collapse of Europe's financial system and the personal bankruptcy of large segments of the French elite.

Relations with England were also delicate. Louis had promised Charles to make William Henry the Sovereign Prince of a Holland rump state and puppet state. He very much preferred that it would be France pulling the strings but there was a distinct possibility that the uncle of the prince would be in control. Louis had not mentioned William in his peace conditions. The very patricians that the French king desired to punish were traditionally pro-French and his natural allies against the pro-English Orangists. He wanted to simply annex Holland and hoped that fear of the Orangists would cause the regenten to surrender the province to him.[38] Of course, the opposite might happen too: that a French advance would lead to the Orangists taking power and capitulating to England. The province of Zealand had already decided to rather make Charles their lord than be subjugated by the French. Only fear of the military power of De Ruyter's fleet had kept them from surrendering outright to the English. De Ruyter did not tolerate any talk of capitulation and intended, if necessary, to take the fleet overseas to continue the fight. Louis feared that the English wanted to claim Staats-Vlaanderen which he saw as French territory because the County of Flanders was a fief of the French crown. In secret he arranged an informal warband of six thousand under Claude Antoine de Dreux to quickly cross the officially neutral Spanish Flanders and execute a surprise assault on the Dutch fortress of Aardenburg, on 25 and 26 June. The attempt was a total failure, the small garrison killing hundreds of attackers and taking prisoner over six hundred Frenchmen who had become pinned down in a ravelin.

Louis also allowed his honour to take precedence over the raison d'état. With the harsh peace conditions he deliberately wanted to humiliate the Dutch.[45] He demanded an annual embassy to the French court asking pardon for their perfidy and presenting a plaquette extolling the magnanimity of the French king. For Louis, a campaign was not complete without some major siege to enhance his personal glory. The quick surrender of so many cities had been somewhat disappointing in this respect. Maastricht having escaped him for the time being, he turned his attention on an even more prestigious object: 's-Hertogenbosch which was considered "inexpugnable". The city was not only a formidable fortress in itself, it was surrounded by a rare fortification belt. Normally its marshy surroundings would make a siege impossible but its presently weak garrison seemed to offer some possibility of success. After Nijmegen had been taken on 9 July, Turenne captured near 's-Hertogenbosch Fort Crèvecœur,[30] which controlled the sluice outlets of the area, halting further inundations. The main French force, thus removed from the Holland war theatre, camped around Boxtel and Louis took residence in Heeswijk Castle.

Orangists take power

The news that the French had penetrated into the heart of the Republic led to a general panic in the cities of the province of Holland. Blaming the States regime for the Dutch collapse, their populations rioted. Members of the city councils were by force replaced by Orangist partisans or in fear of reprisals declared for the cause of the Prince of Orange.[46] Pamphlets accused the regenten of having betrayed the Republic to Louis and De Ruyter of wanting to deliver the fleet to the French.[47] When the French peace terms became known on 1 July, they caused outrage.[48] The result was to bolster Dutch resistance. On 2 July, William was appointed stadtholder of Zealand and on 4 June of Holland.[49] The new stadtholder William III of Orange was given a general mandate to negotiate. Meanwhile, the polders of the Holland Water Line had slowly filled, forming an obstacle to a possible French advance.[50]

Charles thought that William's rise to power allowed to quickly obtain a peace favourable to England. He sent two of his ministers to Holland. They were received with jubilation by the population, who assumed they came to save them from the French. Arriving at the Dutch army camp in Nieuwerbrug, they proposed to install William as monarch of a Principality of Holland. In return he should pay ten million guilders as "indemnities" and formalise a permanent military English occupation of the ports of Brill, Sluys and Flushing. England would respect the French and Münsterite conquests. To their surprise, William flatly refused. He indicated that he might be more pliable if they managed to moderate the French peace terms. They then travelled to Heeswijk Castle, but the Accord of Heeswijk they agreed there was even harsher, England and France promising never to conclude a separate peace. France demanded the areas of Brabant, Limburg and Guelders.[51] Charles tried to right matters by writing a very moderate letter to William, claiming that the only obstacle to peace was the influence of De Witt. William made counteroffers unacceptable to Charles but also on 15 August published the letter to incite the population. On 20 August, Johan and Cornelis de Witt were lynched by an Orangist civil militia, leaving William in control.[52]

Observing that the water around 's-Hertogenbosch showed little sign of receding, Louis became impatient and lifted the siege on 26 July.[53] Leaving his main force of 40,000 behind, he took 18,000 men with him, and marched to Paris within a week, straight through the Spanish Netherlands. He freed 12,000 Dutch prisoners of war for a small ransom, to avoid having to pay for their maintenance.[54] They largely rejoined the Dutch States Army, which could rebuild its strength to 57,000 in August.[54]

War of attrition

In June, the Dutch seemed defeated. The Amsterdam stock market collapsed and their international credit evaporated. Frederick William, the Elector of Brandenburg, in these circumstances hardly dared to threaten the eastern borders of Münster. A single loyal ally remained: the Spanish Netherlands. They well understood that if the Dutch capitulated, they too would be lost. Though officially neutral, and forced to allow the French to transgress their territory with impunity, they openly reinforced the Dutch with thousands of troops.

The Dutch position had stabilised, while concern at French gains brought the support of Brandenburg-Prussia, Emperor Leopold and Charles II of Spain.[55] Instead of a rapid victory, Louis was forced into another war of attrition around the French frontiers; in August, Turenne ended his offensive against the Dutch and proceeded to Germany with 25,000 infantry and 18,000 cavalry.[56] Frederick William and Leopold combined their forces of around 25,000 under the Imperial general Raimondo Montecuccoli; he crossed the Rhine at Koblenz in January 1673 but Turenne forced him to retreat into northern Germany.[57]

The faltering offensive caused financial problems for the allies, especially England. Münster was in an even worse condition; on 27 August it had to abandon the siege of Groningen. Whereas the Dutch had managed to supply the city through waterways at its northern edge, Von Galen's troops were starving and had largely deserted.[58] Also, his siege mortars had lost the artillery duel with the fortress cannon, gradually having been destroyed. Before the end of 1672, the Dutch retook Coevorden[59] and liberated the province of Drenthe, leaving the Allies in possession of only three of the ten—the territories of Drenthe, Staats-Brabant, and Staats-Overmaas were also part of the republic—Dutch provincial areas. The supply lines of the French army were dangerously overextended.[60] In the autumn of 1672, William tried to cut them off, crossing the Spanish Netherlands via Maastricht in forced marches to attack Charleroi, the starting point of the supply route through Liège, though he had to abandon the siege quickly.[60]

The absence of the Dutch field army offered opportunities for the French to renew their offensive. On 27 December, after a severe frost, de Luxembourg began to cross the ice of the Water Line with eight thousand men, hoping to sack The Hague.[61] A sudden thaw cut his force in half and he narrowly escaped to his own lines with the remainder, on his way back massacring the civilian population of Bodegraven and Zwammerdam.[62] This increased the hatred against de Luxembourg. The province of Utrecht was one of the richest regions of Europe and intendant Louis Robert had extorted large sums from its wealthy inhabitants.[63] The French applied the not-unusual method of mettre à contribution: unless noble refugees or Amsterdam merchants made regular payments, their luxury mansions would be burnt down.[64] This made the general the favourite subject of Dutch anti-French propaganda. Special books were published highlighting the outrages he committed, illustrated by Romeyn de Hooghe. The most common Dutch school book, the Mirror of Youth, that had been dedicated to Spanish misdeeds, was now rewritten to reflect French atrocities.

1673

Until the advent of railways in the 19th century, goods and supplies were largely transported by water, making rivers such as the Lys, Sambre and Meuse vital for trade and military operations.[65] The primary French objective in 1673 was the capture of Maastricht, which controlled a key access point on the Meuse; the city surrendered on 30 June.[66]

In June 1673, the French occupation of Kleve and lack of money temporarily drove Brandenburg-Prussia out of the war in the Peace of Vossem.[49] However, in August, the Dutch, Spain and Austria, supported by other German states, agreed the anti-French Alliance of the Hague, joined by Charles IV of Lorraine in October. In September, William recaptured Naarden, while Münster and Cologne left the war in November; with the war expanding into the Rhineland and Spain, French troops withdrew from the Dutch Republic, retaining only Grave and Maastricht.[67]

The alliance between England and Catholic France had been unpopular from the start and although the real terms of the Treaty of Dover remained secret, many suspected them.[68] The Cabal ministry that managed government for Charles had gambled on a short war but when this proved not to be the case, opinion quickly turned against it, while the French were also accused of abandoning the English at Solebay.[69]

Opposition to the alliance with France further increased when Charles' heir, his Catholic brother James, was given permission to marry Mary of Modena, also a devout Catholic. In February 1673, Parliament refused to continue funding the war unless Charles withdrew a proposed Declaration of Indulgence and accepted a Test Act barring Catholics from public office.[70]

After Dutch naval forces defeated an Anglo-French fleet at Texel in August and captured the English settlement of New York City, pressure to end the war became unstoppable and England made peace with the Republic in the February 1674 Treaty of Westminster.[71] To offset these losses, Swedish forces in Swedish Pomerania attacked Brandenburg-Prussia in December 1674 after Louis threatened to withhold their subsidies; this sparked Swedish involvement in the 1675–1679 Scanian War and the Swedish-Brandenburg War whereby the Swedish army tied up the armies of Brandenburg and some minor German principalities plus the Danish Army in the north.[72]

War Expands; 1674–1675

In broad terms, French strategy now focused on retaking Spanish possessions gained in 1667–1668 but returned at Aix-La-Chappelle, while preventing Imperialist advances in the Rhineland. They also supported minor campaigns in Roussillon and Sicily that absorbed Spanish and Dutch naval resources.[73]

Flanders and the Franche-Comté

In Northern Europe, the French recaptured the Franche-Comté by July 1674, while Condé's army in the Spanish Netherlands remained on the defensive. With the advantage of superior numbers, the main Allied field army under William of Orange sought to take the initiative by invading French Flanders, supported by the Spanish, who wanted to recapture Charleroi.[74] This resulted in the indecisive Battle of Seneffe in August 1674; both sides suffered heavy casualties but while the Allies quickly replaced theirs, the French could not.[75] Seneffe confirmed Louis' preference for positional warfare, ushering in a period where siege and manoeuvre dominated military tactics.[76]

The biggest obstacle to Allied success in Flanders were their diverging objectives; the Imperialists wanted to prevent reinforcements reaching Turenne in the Rhineland while the Spanish aimed at recovering losses in the Spanish Netherlands. The Dutch were further split by internal disputes; the powerful Amsterdam mercantile body were anxious to end an expensive war once their commercial interests were secured, while William saw France as a long-term enemy that had to be defeated. This conflict increased once ending the war became a distinct possibility with the recapture of Grave in October 1674, leaving only Maastricht.[77]

Rhineland

During the winter of 1673–1674, Turenne based his troops in Alsace and the Palatinate; despite England's withdrawal from the war in February, his army of less than 8,000 retained a number of English regiments, as Charles II encouraged members to continue serving in order to keep his French subsidies. Monmouth and Churchill were among those who did so, but many others enrolled in the Dutch Scots Brigade, including John Graham, later Viscount Dundee.[78]

Turenne opened the 1674 campaign by crossing the Rhine in June with 7,000 men, hoping to attack Charles of Lorraine before he could combine with forces under Alexander von Bournonville. At the Battle of Sinsheim, the French routed a separate Imperial army led by Aeneas de Caprara but the delay allowed Bournonville to link up with Charles at Heidelberg; reinforced by additional troops, Turenne began crossing the Neckar river and as he did so, the Imperial troops retreated.[79]

Bournonville marched south to the Imperial City of Strasbourg, giving him a base for an attack on Alsace but before doing so, he awaited the arrival of 20,000 troops under Frederick William. To prevent this, Turenne made a night march that enabled him to surprise the Imperial army and comprehensively defeated it at Entzheim on 4 October. As was then accepted practice, Bournonville halted operations until spring but in his Winter Campaign 1674/1675, Turenne inflicted a series of defeats that secured Alsace.[80]

The 1675 Imperial campaign was directed by Montecuccoli, one of the few considered Turenne's equal, who was killed at the Battle of Salzbach on 27 July.[81] This was a serious blow for the French, who were forced back to the Vosges and defeated at the Battle of Konzer Brücke on 11 August. Condé, previously commander in Flanders, took over and stabilised the front but health issues forced him to retire in December 1675 and he was replaced by Créquy.

Spain and Sicily

Activity on this front was largely limited to skirmishing in Roussillon between a French army under Frederick von Schomberg and Spanish forces led by the Duque de San Germán. The Spanish won a minor victory at Maureillas in June 1674 and captured Fort Bellegarde, ceded to France in 1659 and retaken by Schomberg in 1675.[82]

In Sicily, the French supported a successful revolt by the city of Messina against their Spanish overlords in 1674, obliging San Germán to transfer some of his troops. A French naval force under Jean-Baptiste de Valbelle managed to resupply the city in early 1675 and establish local naval supremacy.[83]

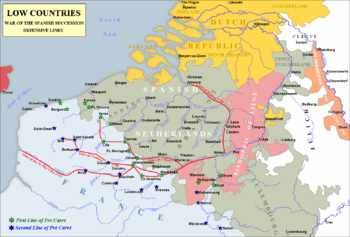

Negotiating the Peace; 1676-1678

On both sides, the last years of the war saw minimal return for their investment of men and money.[84] French strategy in Flanders was largely based on Vauban's proposed line of fortresses known as the Ceinture de fer or iron belt (see Map).[85] This aligned with Louis' preference for siege warfare, which was further reinforced by the death of Turenne and Condé's retirement; their passing removed two of the most talented and aggressive French generals of the 17th century and the only ones with sufficient stature to challenge him.[86]

In Germany, Imperial forces recaptured Philippsburg in September 1676 but the French stabilised their front. In an attempt to regain some of their losses, the Imperialists assembled an army in the Rhineland under Charles of Lorraine but minor defeats at Rheinfelden and Ortenbach in July 1678 ended these hopes. The French followed up by capturing Kehl and the bridge over the Rhine near Strasbourg, thus ensuring control of Alsace. The Spanish theatre remained largely static; French victory at Espolla in July 1677 left the strategic position unchanged but their losses worsened the crisis faced by the Spanish administration.[87]

Dutch admiral De Ruyter was killed at Augusta in April 1676 and the French achieved naval supremacy in the Western Mediterranean when their galleys surprised the Dutch/Spanish fleet at anchor at Palermo in June.[88] However, French intervention had been opportunistic; friction arose with the anti-Spanish rebels, the cost of operations was prohibitive and Messina was evacuated in early 1678.[87]

The peace talks that began at Nijmegen in 1676 were given a greater sense of urgency in November 1677 when William married his cousin Mary, Charles II of England's niece. An Anglo-Dutch defensive alliance followed in March 1678, although English troops did not arrive in significant numbers until late May. This allowed Louis to improve his negotiating position by capturing Ypres and Ghent in early March, before signing a peace treaty with the Dutch on 10 August.[89]

The Battle of Saint-Denis was fought three days later on 13 August, when a combined Dutch-Spanish force attacked the French army under Luxembourg. While a French tactical victory, it ensured Mons would remain in Spanish hands and on 19 August, Spain and France agreed an armistice, followed by a formal peace treaty on 17 September.

1678: the Peace of Nijmegen and its consequences

The Peace of Nijmegen confirmed most of the French gains. Louis XIV, having successfully fought a powerful coalition, came to be known as the 'Sun King' in the years that followed this war. Nevertheless, while favorable to France, the peace terms were significantly worse than those that had been available in July 1672.[90] France returned Charleroi, Ghent and other towns in the Spanish Netherlands, in return for Spain ceding Franche-Comté, Ypres, Maubeuge, Câteau-Cambrésis, Valenciennes, Saint-Omer and Cassel; with the exception of Ypres, all of these remain part of modern France.[91]

Brandenburg managed to occupy Swedish Pomerania completely in September 1678, France's ally Sweden regained it by the 1679 Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye but this did little to improve its perilous financial position. In addition, Frederick William's resentment at being forced to give up what he saw as his own territory turned Brandenburg-Prussia into an implacable opponent.[92]

The Dutch recovered from the near disaster of 1672 to prove they were a permanent and significant power in Northern Europe. Arguably, their most lasting gain was William's marriage to Mary and his arrival as one of the most powerful statesmen in Europe, with sufficient stature to hold together an anti-French coalition. It also showed that while significant sections of the English mercantile and political class were anti-Dutch on commercial grounds, there was no popular support for an alliance with France.

In Spain, defeat led to the Queen Regent, Mariana of Austria, being replaced by her long-term rival, the pro-French John of Austria the Younger. She returned to power after his death in September 1679 but not before he arranged the marriage of Charles II of Spain to Louis' niece, 17-year-old Marie Louise of Orléans in November 1679.[93]

Louis had the enormous advantage of a unified strategy, in contrast to the differing objectives of his opponents; while this remained a factor, 1672-1678 showed the threat of French expansion over-ruled all other considerations and that France was not strong enough to impose its objectives without support. His inability to recognise this and the 1683–1684 War of the Reunions led to the creation of the anti-French Grand Alliance in 1688, which held together through the 1688–1697 Nine Years War and the 1701–1714 War of the Spanish Succession.[94]

Chronological list of key events

- 1672 – Battle of Solebay (7 June, Third Anglo-Dutch War)

- 1673 – Battle of Schooneveld (7–14 June, Third Anglo-Dutch War)

- 1673 – Siege of Maastricht (13–26 June)

.jpg) The Battle of Solebay, May 1672

The Battle of Solebay, May 1672 - 1673 – Battle of Texel (21 August; Third Anglo-Dutch War)

- 1673 – Siege of Bonn (October–November)

The Siege of Besançon in 1674

The Siege of Besançon in 1674 - 1673 – Siege of Werl

- 1673 – Battle of Heringen

- 1674 – Occupation of Acadia

- 1674 – Siege of Besançon (April–May)

- 1674 – Battle of Sinsheim (16 June)

- 1674 – Battle of Ladenburg (7 July)

- 1674 – Battle of Seneffe (11 August)

- 1674 – Battle of Enzheim (4 October)

- 1674 – Battle of Mulhouse (29 December)

- 1675 – Battle of Turckheim (5 January)

- 1675 – Battle of Fehrbellin (28 June; Brandenburg-Swedish War)

- 1675 – Battle of Nieder Sasbach (27 July)

- 1675 – Battle of Konzer Brücke (11 August)

- 1676 – Battle Alicudi (8 January)

- 1676 – Battle of Messina (25 March)

- 1676 – Battle of Golfo di Augusta (22 April)

- 1676 – Battle of Jasmund (25 May; Danish-Swedish (Scanian) War of 1675–1679)

- 1676 – Battle of Öland (11 June, Scanian War of 1675–1679)

- 1676 – Battle of Palermo (2 June)

- 1676 – Battle of Halmstad (17 August; Scanian War of 1675–1679)

- 1676 – Battle of Lund (4 December; Scanian War of 1675–1679)

- 1677 – Siege of Valenciennes (28 February – 17 March)

- 1677 – Siege of Cambrai (28 March – 17 April)

- 1677 – Battle of Cassel (11 April)

- 1677 – Battle of Køge Bay (1 July; Scanian War of 1675–1679)

- 1677 – Battle of Landskrona (24 July; Scanian War of 1675–1679)

- 1677 – Battle of Kochersberg (7 October)

- 1678 - Battle of Warksow (18 January; Brandenburg-Swedish War )

- 1678 – Siege of Offenburg

- 1678 – Siege of Ypres (18–25 March)

- 1678 – Battle of Rheinfelden (6 July)

- 1678 – Battle of Ortenbach, also known as Battle of Gengenbach; (23 July)

- 1678 – Battle of Saint-Denis (14 August)

Footnotes

- An attitude described at the time as Gallus amicus, non-vicinus or "The Frenchman should be a friend, not a neighbour"

- Officers 'owned' their companies and regiments; since they were paid per man, padding rosters was common practice

References

- Clodfelter, Michael (1992). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1500–2000 (2017 ed.). McFarland & Co. p. 47. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 47.

- 1672 Disaster Year Archived 24 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Rijksmuseum

- Boxer, CR (1969). "Some Second Thoughts on the Third Anglo-Dutch War, 1672–1674". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 19: 74–75. doi:10.2307/3678740. JSTOR 3678740.

- Israel 1990, pp. 197–199.

- Rowen 1978, pp. 121–125.

- Geyl 1936, pp. 311.

- Hutton 1986, pp. 299–300.

- Rowan 1954, pp. 9–12.

- Geyl 1936, pp. 312–316.

- Lynn 1996, pp. 109–110.

- Kenyon 1993, pp. 67–68.

- Hutton 1986, p. 309.

- Frost 2000, p. 209.

- Black 2011, pp. 97–99.

- Lynn 1999, p. 113.

- Shomette & Haslach 2002, p. 25.

- Hutton 1986, p. 302.

- Rowen 1978, p. 758.

- Rowen 1978, p. 752.

- Van Nimwegen 2010, pp. 440–441.

- Boxer 1969, p. 71.

- Clodfelter 1992, p. 46.

- Rowen 1978, p. 771.

- Rowen 1978, pp. 755–756.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 112.

- Lynn 1999, p. 113.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 134.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 135.

- Lynn 1999, p. 115.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 139.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 140.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 141.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 149.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 146.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 150.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 145.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 201.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 151.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 152.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 153.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 162.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 163.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 165.

- Troost 2001, p. 87.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 158.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 205.

- Reinders, Michel (2013). Printed Pandemonium: Popular Print and Politics in the Netherlands 1650–72. Brill. pp. 108–110. ISBN 978-9004243187.

- Young, William (2004). International Politics and Warfare in the Age of Louis XIV and Peter the Great. iUniverse. p. 131. ISBN 978-0595329922.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 202.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 183.

- Lynn 1999, p. 114.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 185.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 220.

- Smith 1965, p. 200.

- Lynn 1999, p. 117.

- Lynn 1999, p. 118.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 210.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 285.

- Panhuysen 2016, pp. 86.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 269.

- Panhuysen 2016, pp. 87.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 197-198.

- Panhuysen 2009, p. 200.

- Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688–1697: The Operations in the Low Countries (2013 ed.). Manchester University Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0719089961.

- Lynn 1999, p. 120.

- Young, p. 132

- Boxer, CR (1969). "Some Second Thoughts on the Third Anglo-Dutch War, 1672–1674". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 19: 74–75. doi:10.2307/3678740. JSTOR 3678740.

- Palmer, Michael (2005). Command at Sea: Naval Command and Control Since the Sixteenth Century (2007 ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-0674024113.

- Hutton, Ronald (1989). Charles II: King of England, Scotland and Ireland. Clarendon Press. pp. 345–346. ISBN 978-0198229117.

- Boxer, pp 88–90

- Frost p. 210

- Young, 2004, p. 132.

- Lynn 1999, p. 125.

- Van Nimwegen, Olaf (2010). The Dutch Army and the Military Revolutions, 1588–1688. Boydell Press. p. 479. ISBN 978-1843835752.

- Lynn, p. 125

- Jacques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity through the Twenty-first Century, Volume 2, F–O. Greenwood. p. 408. ISBN 978-0313335389.

- Linklater, Magnus (2004). "Graham, John, first viscount of Dundee [known as Bonnie Dundee". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11208. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lynn. p. 129.

- Lynn 1999, pp. 131–132.

- Lynn 1999, p. 141.

- Lynn 1999, p. 135.

- Blackmore, RT (2011). Warfare on the Mediterranean in the Age of Sail: A History, 1571–1866. McFarland & Co. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0786447992.

- Nolan, Cathal (2008). Wars of the Age of Louis XIV, 1650–1715: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization. Greenwood. p. 126. ISBN 978-0313330469.

- Wolfe, Michael (2009). Walled Towns and the Shaping of France: From the Medieval to the Early Modern Era. AIAA. p. 149. ISBN 978-0230608122.

- Starkey, Armstrong (2003). War in the Age of Enlightenment, 1700–1789. Praeger. p. 38. ISBN 978-0275972400.

- Nolan 2008, p. 126

- Lynn 1999, pp. 148–149.

- Lesaffer, Randall. "The Wars of Louis XIV in Treaties (Part V): The Peace of Nijmegen (1678–1679)". Oxford Public International Law. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Lynn 1999, p. 159.

- "Treaty of Peace between France and Spain, signed at Nimeguen, 17 September 1678". Oxford International Public Law. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Clark, Christopher M. (2007). Iron kingdom: the rise and downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947. Penguin. p. 50. ISBN 978-0140293340.

- Barton, Simon (2008). A History of Spain (2009 ed.). Palgrave. p. 146. ISBN 978-0230200128.

- Nolan 2008, p. 128

Sources

- Barton, Simon (2008). A History of Spain. Palgrave. ISBN 978-0230200128.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Black, Jeremy (2011). Beyond the Military Revolution: War in the Seventeenth Century World. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230251564.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blackmore, RT (2011). Warfare on the Mediterranean in the Age of Sail: A History, 1571-1866. McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0786447992.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boxer, CR (1969). "Some Second Thoughts on the Third Anglo-Dutch War, 1672-1674". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 19: 67–94. doi:10.2307/3678740. JSTOR 3678740.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clark, Christopher M. (2007). Iron kingdom: the rise and downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947. Penguin. ISBN 978-0140293340.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688-1697: The Operations in the Low Countries. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719089961.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clodfelter, Michael (1992). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1500-2000. McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0786474707.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frost, Robert (2000). The Northern Wars; State and Society in Northeastern Europe 1558-1721. Routledge. ISBN 978-0582064294.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Geyl, P (1936). "Johan de Witt, Grand Pensionary of Holland, 1653–72". History. 20 (80): 303–319. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1936.tb00103.x. JSTOR 24401084.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutton, Ronald (1989). Charles II: King of England, Scotland and Ireland. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198229117.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutton, R (1986). "The Making of the Secret Treaty of Dover, 1668-1670". The Historical Journal. 29 (2): 297–318. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00018756. JSTOR 2639064.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Israel, Jonathan (1989). Dutch Primacy in World Trade, 1585–1740 (1990 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198211396.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jacques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity through the Twenty-first Century, Volume 2, F–O. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0313335389.

- Kenyon, JP (1986). The History Men: The Historical Profession in England since the Renaissance (1993 ed.). Weidenfeld & Nicolson.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lynn, John (1996). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667-1714 (Modern Wars in Perspective). Longman. ISBN 978-0582056299.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nolan, Cathal (2008). Wars of the Age of Louis XIV, 1650-1715: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0313330469.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Palmer, Michael (2005). Command at Sea: Naval Command and Control Since the Sixteenth Century. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674024113.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Panhuysen, Luc (2009). Rampjaar 1672: Hoe de Republiek aan de ondergang ontsnapte. Uitgeverij Atlas. ISBN 9789045013282.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Panhuysen, Luc (2016). Oranje tegen de Zonnekoning: De strijd van Willem III en Lodewijk XIV om Europa. De Arbeiderspers. ISBN 978-9029538718.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reinders, Michel (2013). Printed Pandemonium: Popular Print and Politics in the Netherlands 1650-72. Brill. ISBN 978-9004243187.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rowen, Henry Herbert (1978). John de Witt, Grand Pensionary of Holland, 1625-1672 (2015 ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691600437.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rowen, Herbert H (1954). "John De Witt and the Triple Alliance". The Journal of Modern History. 26 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1086/237659. JSTOR 1874869.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sommerville, J. P. (16 January 2008), The wars of Louis XIVCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Rhea Marsh, Spain: A Modern History (University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1965)

- Starkey, Armstrong (2003). War in the Age of Enlightenment, 1700–1789. Praeger. ISBN 978-0275972400.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Troost, W. (2001). Stadhouder-koning Willem III: Een politieke biografie. Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 90-6550-639-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Nimwegen, Olaf (2010). The Dutch Army and the Military Revolutions, 1588–1688. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843835752.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolf, John (1962). The Emergence of European Civilization. Joanna Cotler Books. ISBN 978-0060471804.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolfe, Michael (2009). Walled Towns and the Shaping of France: From the Medieval to the Early Modern Era. AIAA. ISBN 978-0230608122.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Young, William (2004). International Politics and Warfare in the Age of Louis XIV and Peter the Great. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0595329922.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- "The first stadtholderless period". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 21 September 2019.