Battle of Entzheim

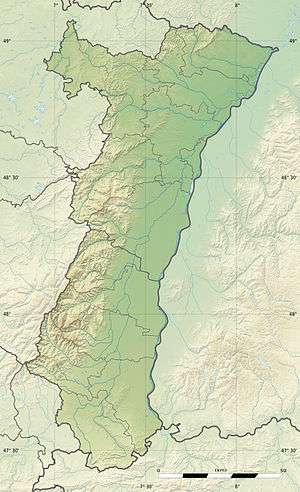

The Battle of Entzheim, also called Enzheim, or Ensheim, took place on 4 October 1674 near the town of Entzheim, south of Strasbourg in Alsace. Fought during the 1672 to 1678 Franco-Dutch War, it featured a French army under Turenne against an Imperial force commanded by Alexander von Bournonville.

| Battle of Entzheim | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Franco-Dutch War | |||||||

Battle of Enzheim (Martinet ill.; E. Ruhierre graveur.) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

22,000 men 30 guns |

38,000 men 50 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,500, killed, wounded and missing | 3,000–4,000 killed, wounded and missing[1] | ||||||

Although the battle was inconclusive, it is generally considered a French strategic victory, since Turenne prevented a larger Imperial army from invading Eastern France. He also benefited from vastly superior logistics support, and the combination set the scene for his subsequent Winter Campaign.

Background

In the 1667 to 1668 War of Devolution, which preceded the Franco-Dutch War, France had captured the Franche-Comté, and most of the Spanish Netherlands. Under pressure from the Triple Alliance, composed of the Dutch Republic, England and Sweden, Louis XIV relinquished many of his gains in the 1668 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle.[2][3]

Louis viewed possession of the Spanish Netherlands as essential for French trade, and went to war in 1667 when he realised the Dutch would never agree to this. After 1668, he decided the best way to achieve this was to first defeat the Republic, and began planning the Franco-Dutch War.[4] He undermined the Triple Alliance by negotiating the 1670 Treaty of Dover with Charles II of England, who agreed to join France against the Dutch, and contribute a brigade of 4,000 British troops. The treaty contained secret clauses, not revealed until 1771, including payment personally to Charles of £230,000 per year.[5]

Preparations were completed in April 1672, when Charles XI of Sweden accepted French subsidies in return for neutrality, and in May, France invaded the Dutch Republic. Initially, the French forces were very successful, but by July, the Dutch position stabilised, while concern at French gains brought support for the Republic from Brandenburg-Prussia, the Emperor Leopold, and Charles II of Spain. In August 1672, an Imperial army appeared on the upper Rhine, forcing Louis into another war of attrition around the French frontiers.

The French army in Germany was led by Turenne (1611–1675), considered one of the greatest generals of the period. Over the next two years, he won victories over superior Imperial forces under Bournonville and Raimondo Montecuccoli, the only commander contemporaries considered his equal.[6]

After 1673, Turenne was forced onto the defensive, his objectives being to retain French gains on the upper Rhine, and prevent the Imperials from linking up with the Dutch. France was over-extended, a problem that got worse in January 1674, when Denmark joined the Alliance; and furthermore in February, when England and the Dutch Republic made peace ending the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674) by signing the Treaty of Westminster.[7] In 1674, the main campaign took place in Flanders, while an Imperial army opened a second front in Alsace.[8]

In September, Bournonville crossed the Rhine at Strasbourg with 40,000 men, a diplomatic coup for Emperor Leopold. Despite being part of the Holy Roman Empire, the city had remained neutral, and its bridge was a major crossing point. Bournonville expected another 20,000 men led by Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia, the Great Elector; once combined, they would overwhelm the smaller French army, and invade eastern France.

Although England had left the war, Turenne's army of 22,000 contained several English units,[9] who were encouraged to remain in French service to ensure Charles was paid for them.[10] One of these was commanded by Irish Catholic George Hamilton, another by John Churchill, later Duke of Marlborough.[11]

French armies of the period held significant advantages over their opponents; an undivided command, talented generals, and vastly superior logistics. Reforms introduced by François-Michel le Tellier, Marquis de Louvois, the Secretary of War, helped maintain large field armies that could be mobilised much more quickly than those of their adversaries. This allowed the French to mount offensives in early spring before their opponents were ready, seize their objectives and then assume a defensive posture.[12]

Although inferior in numbers, these advantages allowed Turenne to attack his opponents individually before they could combine. At Sinsheim on 16 June, he inflicted heavy casualties on an Imperial force under Aeneas de Caprara,[13] although he was unable to prevent him linking up with Bournonville. Their combined army of 38,000 then moved to Entzheim, where they awaited Frederick William. Turenne occupied Molsheim on the night of 2–3 October. On the morning of 4 October, he advanced eastwards towards Entzheim, crossing the Bruche River, covered by a thick mist that gave way to rain, cutting Bournonville off from Strasbourg.[14]

The battle

Turenne had 32,000 men and 30 guns; Bournonville 38,000 and 50 guns.[15] As the French arrived, each army formed into two lines, with infantry in the centre and cavalry on the wings; Turenne also placed a cavalry reserve behind each line, and posted small units of musketeers to cover the gaps between his cavalry squadrons. Entzheim lay in Bournonville's centre, with a vineyard, backed by woods, to the east; while a forested area known as the Little Wood, and a ravine just to its south protected the Imperial left.[8]

Both sides recognised the importance of the Little Wood; Turenne sent eight battalions of infantry to assault it, in the face of a sustained Imperial artillery barrage. Future Marshall of France, Louis Francois de Boufflers, led his dragoons into the attack[16] but rain and mud impeded the French artillery as it tried to move forward.[17] Bournonville responded to the French assault by transferring most of the infantry from his second line and reserve,[18] while Turenne reinforced the attack with three battalions from his first line and the cavalry of his right wing. The French managed to take the Little Wood, but were then ejected by an Imperial counterattack.

Seeing the French centre weakened by the transfer of so many units towards the wood, Bournonville launched his cavalry against what he hoped were two weak points in the French line.[19] A part attacked the seven battalions in the centre of the French first line, while de Caprara led the rest against the French cavalry on the left, commanded by Guy Aldonce de Durfort de Lorges. The French infantry held off the Imperial cavalry, and although Caprara's attack drove in the first line of the French cavalry, the second and reserve lines forced him back to the starting line.[20]

The battle reached stalemate, until another assault by the English regiments, including the one led by Churchill,[21] captured the Little Wood, threatening the Imperial left. Churchill reported the attack cost his unit 11 of 22 officers, while another lost all its officers and over half their men; in private, he was critical of Turenne's deployment.[22][23] After a series of failed cavalry attacks on the French centre and left, Bournonville ordered a retreat, having sustained around 3,000–4,000 casualties.[1] The Imperials entered winter quarters near Colmar, but Turenne did not pursue him; his own losses were around 3,500 men, many incurred by the English units, which were disbanded. He took his army north to Dettwiller between Saverne and Haguenau, where his exhausted troops could rest and refit.[24]

Aftermath

The Imperials entered winter quarters near Colmar, but Turenne did not pursue him; his own losses were around 3,500 men, many incurred by the English units, which were disbanded. He took his army north to Dettwiller between Saverne and Haguenau, where his exhausted troops could rest and refit.[25] Entzheim was a tactical draw, but a strategic French victory; despite superior numbers, Bournonville had been prevented from entering French-held territory.[26]

The campaign that started in June 1674 and ended with his death in July 1675 has been described as 'Turenne's most brilliant campaign.' Significantly outnumbered, he used stealth and boldness to fight the Imperial army to a standstill at Entzheim; with his enemy now inactive, he was able to plan the winter movement that would culminate in decisive victory at the Battle of Turckheim.

Entzheim still exists, but most of the battlefield now lies beneath Strasbourg International Airport.[27]

Notes and References

- Clodfelter 2008, p. 46, left column, line 35: "The result was a tactical standoff with both sides retiring, the French having lost 3,500 killed, wounded or missing, the Imperialists 3000–4000."

- Macintosh 1973, p. 165.

- Phillips 1910, p. 450, line 2: "The treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle left to France all the conquests made in Flanders during the campaign of 1667 ... On the other hand, France restored to Spain the cities of Cambrai, Aire and Saint-Omer, as well as the province of Franche-Comté."

- Lynn 1999, pp. 109-110.

- Hutton 1989, p. 271, line 9: "Charles agreed to join sixty ships to thirty French vessels, for an annual subsidy of about £230,000. He also promised to sent 4,000 infantry to join the French army, whom Louis would pay."

- Guthrie 2003, p. 239, line 30: "He was considered the only general able to match Turenne ..."

- Hutton 1989, p. 317, line 2: "The result was the Treaty of Westminster, drafted at Arlington's house ... and sealed on 9 February. By gaining the salute in British waters, good terms for the Surinam settlers, arbitration of the East Indian trade disputes, and an indemnity, England could be said to have emerged without loss of honour or territory ..."

- Chandler 1979, p. 40.

- Chandler 1979, p. 7: "Churchill was present at the battles of Sinzheim (16 June) and Entzheim (4 October), both fought under difficult conditions."

- Kenyon 1986, p. 83.

- Holmes 2008, p. 80.

- Black 2011, pp. 97–99.

- Clodfelter 2008, p. 46, left column, line 22: "In the Rhineland, Turenne fought his last and possibly most brilliant campaign. Crossing the Rhine of June 14, 1674, the French general defeated General Enea Sylvio Caprara with 9000 Imperialist troops at Sinzheim on "

- Rousset 1865, p. 86, last line: "L'artillerie ouvrit le feu à neuf heures du matin sous un ciel gris et une pluie battante."

- Clodfelter 2008, p. 46, left column, line 30: "Turenne fought a second major battle on October 4, 1674 at Enzheim, leading 32,000 men and 30 guns against Prince Alexandre-Hippolyte of Bournonville at the head of 38,0000 men and 50 guns."

- Lynn 1999, p. 132, line 1: "The young brigadier, Louis-François, marquis de Boufflers, led dragoons into the wood ..."

- Lynn 1999, p. 132, line 8: "A constant rain made it difficult for Turenne to bring up artillery to support the battle on this flank."

- Lynn 1999, p. 132, line 4: "Bournonville threw in most of the infantry from his second line and his reserve."

- Lynn 1999, p. 132, line 15: "The removal of three battalions from the first line and the shift of the French right into the battle for the woods left a hole in the French centre that Bournonville now exploited with his cavalry."

- Lynn 1999, p. 132, line 17: "One body of horsemen charged the French squadrons on the left and another bore down on the remaining seven battalions in the first line."

- Jones 1993, p. 16, line 26: "... by October he [Churchill] was at the head of his regiment at the battle of Enzheim, where his conduct earned Turenne's praise."

- Jones 1993, p. 16, line 30: "... the young officer of twenty-four [Churchill] ... felt himself qualified to offer strong criticism of his renowned general for failing to concentrate his forces ..."

- Holmes 2008, pp. 80–81.

- Lynn 1999, p. 132, line 29: "... so the marshal was compelled by this superior force to fall back to Deittweiler where his entrenched camp protected both Saverne and Haguenau."

- Lynn 1999, p. 132.

- Tucker 2010, p. 651, left column, line 15: "After blunting an allied invasion of Lorraine, Turenne moves to attack Bournonville's far larger allied force.

- Google (20 June 2020). "Strasbourg airport" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

Sources

- Black, Jeremy (2011). Beyond the Military Revolution: War in the Seventeenth Century World. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230251564.

- Chandler, David G (1979). Marlborough as Military Commander (2nd, illustrated ed.). Batsford. ISBN 978-0713420753.

- Clodfelter, Michael (2008). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1494-2007 (3rd ed.). McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-3319-3.

- Guthrie, William P. (2003). The Later Thirty Years War: From the Battle of Wittstock to the Treaty of Westphalia (Contributions in Military Studies). Praeger. ISBN 978-0313324086.

- Holmes, Richard (2008). Marlborough: Britain’s Greatest General: England's Fragile Genius. Harper Press. ISBN 978-0007225712.

- Hutton, Ronald (1989). Charles II King of England, Scotland and Ireland. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198229117.

- Jones, James Rees (1993). Marlborough. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521-37571-1.

- Kenyon, John Philipps (1986). The History Men: The Historical Profession in England since the Renaissance. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Lynn, John A. (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714. Addison Wesley Longman. ISBN 978-0582056299.

- Macintosh, Claude Truman (1973). French Diplomacy during the War of Devolution, the Triple Alliance and the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (PhD). Ohio State University.

- Phillips, Walter Alison (1910). Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Aix-la-Chapelle, Congresses of. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1 (11 ed.). New York: The Encyclopaedia Britannica Company. pp. 449–450.

- Rousset, Camille (1865). Histoire de Louvois et de son administration politique et militaire jusqu’à la paix de Nimègue (in French). 2. Paris: Didier & Cie.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict. Santa Barbara, California: ABC CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-667-1.

External links

- "Turenne 1611-1675". Musée virtuel du Protestantisme. Retrieved 5 October 2018.