Battle of Altenheim

The Battle of Altenheim took place on 1 August 1675 during the 1672-1678 Franco-Dutch War near Altenheim, in modern Baden-Württemberg, between a French army jointly commanded by the Marquis de Vaubrun and the Comte de Lorges and an Imperial Army under Raimondo Montecuccoli. Having lost their commander Marshall Turenne on 27 July, the French retreated over the Rhine, using the bridge at Altenheim; the Imperialists tried to prevent them but were unable to do so, despite heavy casualties on both sides.

| Battle of Altenheim | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Franco-Dutch War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

10,000 infantry, 9,000 cavalry, 1,000 dragoons 30 guns [1] | 30,000 [lower-alpha 2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,000 | 4,500 [2] | ||||||

Background

During the 1667-1668 War of Devolution, France captured most of the Spanish Netherlands but under the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, it was forced to relinquish most of these gains by the Triple Alliance between the Dutch Republic, England and Sweden.[3]

Louis XIV now moved to break up the Alliance before making another attempt on the Spanish Netherlands. In return for large subsidies, Sweden agreed to remain neutral and to attack its regional rival, Brandenburg-Prussia if it attempted to intervene. In 1670, Charles II of England signed the Treaty of Dover, agreeing to an alliance with France against the Dutch, and the provision of 6,000 English and Scottish troops for the French army.[4] It also contained a number of secret provisions, not revealed until 1771, one being the payment by Louis to Charles of £230,000 per year for the services of this Brigade.[5]

France invaded the Dutch Republic in May 1672 and seemed at first to have achieved an overwhelming victory. However, the Dutch position stabilised, while concern at French gains brought support from Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia, Emperor Leopold and Charles II of Spain.[6] Louis was now forced into another war of attrition around the French frontiers and in August, an Imperial army opened a new front in the Rhineland.[7]

The French army in Germany was led by Turenne, (1611-1675), considered the greatest general of the period.[8] Over the next two years, he won a series of victories over superior Imperial forces led by Alexander von Bournonville and Raimondo Montecuccoli, the one commander contemporaries viewed as equal to Turenne.[9] France found itself over-extended, a problem that increased in January 1674 when Denmark joined the Alliance; in February, England left the war by signing the Treaty of Westminster with the Dutch Republic.[10]

The campaign that started in June 1674 and ended with his death in July 1675, has been described as 'possibly Turenne's most brilliant campaign.'[11] Significantly outnumbered, he fought Bournonville to a standstill at Entzheim in early October, followed by a surprise winter attack that culminated in another decisive victory at the Battle of Turckheim in January 1675.[12]

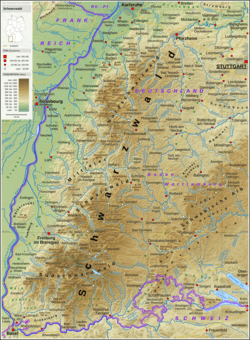

Montecuccoli brought up another 25,000 men and combined with the remnants of Bournonville's force, this meant Turenne was outnumbered once more. By late May, the Imperial army was at Oberkirch, preparing to take the bridge at Kehl and re-establish contact with Strasburg. The next two months were spent in a series of marches and counter-marches, with Turenne seeking to remain in close contact with the Imperialists. Local geography restricted them to a relatively narrow corridor between the left bank of the Rhine and the Black Forest, other factors being a dependence on waterways for moving supplies, the need to obtain forage for cavalry and transport, while persistent rain in the first half of June made movement almost impossible.[13]

A number of skirmishes and encounters took place in July as each commander attempted to outwit the other, the Marquis de Vaubrun being wounded in one of these on 24 July. On 25 July, Montecuccoli stopped between Großweier and Sasbach, as he waited for his subordinate Aeneas de Caprara to rejoin him from Offenburg. On the morning of 27th, Turenne arrived at Salzbach, looking for an opportunity to attack; he was checking the position of his artillery in the afternoon, when he was killed by a cannonball.[14]

The Battle

_-_MV_1042.jpg)

The news of Turenne's death was initially concealed from the troops, but it soon became common knowledge. Turenne had no direct subordinate but two 'Lieutenant-Generals,' his nephew, the Comte de Lorges and the Marquis de Vaubrun, who rotated the position on a daily basis. According to another officer, the Marquis de Feuquières, de Lorges and de Vaubrun now spent the next three days arguing who should assume command, at one point drawing swords on each other in the middle of the camp.[15]

The French baggage train was stationed in the nearby village of Willstätt; hoping to capture it and re-establish direct communication with Strasburg, a force of Imperial dragoons and cavalry unsuccessfully attacked on 29 July. De Lorge and de Vaubrun finally compromised by agreeing to rotate command daily and on 31 July, the French army moved towards the bridge over the Rhine at Altenheim, a small town now part of the municipality of Neuried in Baden-Württemberg. As they did so, Montecuccoli followed up, once more threatening to take Willstätt and the French supplies.[16]

A second dispute broke out between De Lorges and de Vaubrun as to whether to continue towards the bridge or save the stores. They decided to first destroy the stores, then cross, but the delay left the army divided when night came on 31st, with Vaubrun's vanguard on the French side of the Rhine and the rest under de Lorges yet to cross.[17] To reach the Rhine, de Lorges' troops had to first cross a smaller tributary called the Schutter. As they began doing so on 1 August, Montecuccoli attacked, while simultaneously cutting off their retreat by taking the bridge at Altenheim. Vaubrun had been wounded in the leg on 24 July and was tied onto his horse; he counter-attacked with 16 squadrons of cavalry and eight battalions of infantry and was killed in the action, but the Imperialists were driven out of Altenheim. The French rearguard was composed of the Brigade de Champagne, which included the British regiments; it repulsed a series of assaults and fighting ended around evening, with both sides withdrawing.[17]

De Feuquières, part of the Brigade de Champagne, described this action in his 'Memoirs' as one of the 'most glorious in the history of France.' The brigade lost 10 captains and 25 lieutenants killed, French casualties being around 3,000 to the Imperialists 4,500.[18]

Aftermath

The French withdrew to Sélestat and the Prince of Condé assumed command; he was a capable general, responsible for victory at Seneffe in 1674 but in poor health and this would be his last campaign. On 11 August, a French force of 15,000 sent to relieve Trier was defeated at Konzer Brücke and Trier surrendered in September. Unwilling to risk losing the only remaining French army in the Rhineland and estimating Imperial strength at over 30,000, Condé took up position at the fortified town of Châtenois. Montecuccoli attempted to lure him out, but with French cavalry raiding his supply lines and winter coming on, he abandoned the attempt, In the first week of November, his army recrossed the Rhine and went into winter quarters.[19]

Notes

- Not to be confused with the nearby French town of Altenheim

- Maximum; these are the figures given by De Périni at the beginning of the campaign.

References

- De Périni, Hardÿ (1896). Batailles françaises. Ernest Flammarion, Paris. p. 146. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- De Périni, Hardÿ (1896). Batailles françaises. Ernest Flammarion, Paris. p. 161. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- Lynn, John (1996). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667-1714 (Modern Wars In Perspective). Longman. p. 109. ISBN 978-0582056299.

- Lynn, John (1996). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667-1714 (Modern Wars In Perspective). Longman. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0582056299.

- J. P. Kenyon, The History Men. The Historical Profession in England since the Renaissance. Second Edition (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1993), pp. 67-68.

- Smith, Rhea (1965). Spain; A Modern History. University of Michigan Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-0472071500.

- Lynn 1999, p. 117.

- "Turenne 1611-1675". Musée virtuel du Protestantisme. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- Guthrie, William (2003). The Later Thirty Years War: From the Battle of Wittstock to the Treaty of Westphalia (Contributions in Military Studies). Praeger. p. 239. ISBN 978-0313324086.

- Davenport, Frances (1917). "European Treaties bearing on the History of the United States and its Dependencies". p. 238. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2008). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1494-2007. McFarland & Co. p. 46. ISBN 978-0786433193.

- Lynn, 1999, 127.

- De Périni, p. 151-152.

- Lynn, 1999, 141.

- De Périni, Hardÿ (1896). Batailles françaises. Ernest Flammarion, Paris. p. 161. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- Almon, John (1760). A new military dictionary: or, the field of war. Containing a particular account of the most remarkable battles, sieges, bombardments, and relate to Great Britain and her dependencies (2018 ed.). Gale ECCO. p. 4. ISBN 978-1385700778.

- Almon 1760, p. 4.

- De Périni, p. 161.

- De Périni, p. 168-171.

Sources

- Almon, John; A new military dictionary: or, the field of war. Containing a particular account of the most remarkable battles, sieges, bombardments, and relate to Great Britain and her dependencies; (First published 1760, Gale ECCO, 2018 ed);

- Clodfelter, Micheal; Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1494-2007; (McFarland & Co, 2008);

- Davenport, Frances; European Treaties bearing on the History of the United States and its Dependencies; (Published 1917, Andesite Press, 2017 ed);

- De Périni, Hardÿ; Batailles françaises, 1672-1700; (Ernest Flammarion, Paris, 1896);

- Guthrie, William; The Later Thirty Years War: From the Battle of Wittstock to the Treaty of Westphalia (Contributions in Military Studies); (Praeger, 2003);

- Kenyon, J.P.; The History Men. The Historical Profession in England since the Renaissance; (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1993);

- Lynn, John; The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667-1714 (Modern Wars In Perspective); (Longman, 1996);

- Smith, Rhea; (1965). Spain; A Modern History; (University of Michigan Press, 1965);