Battle of Seneffe

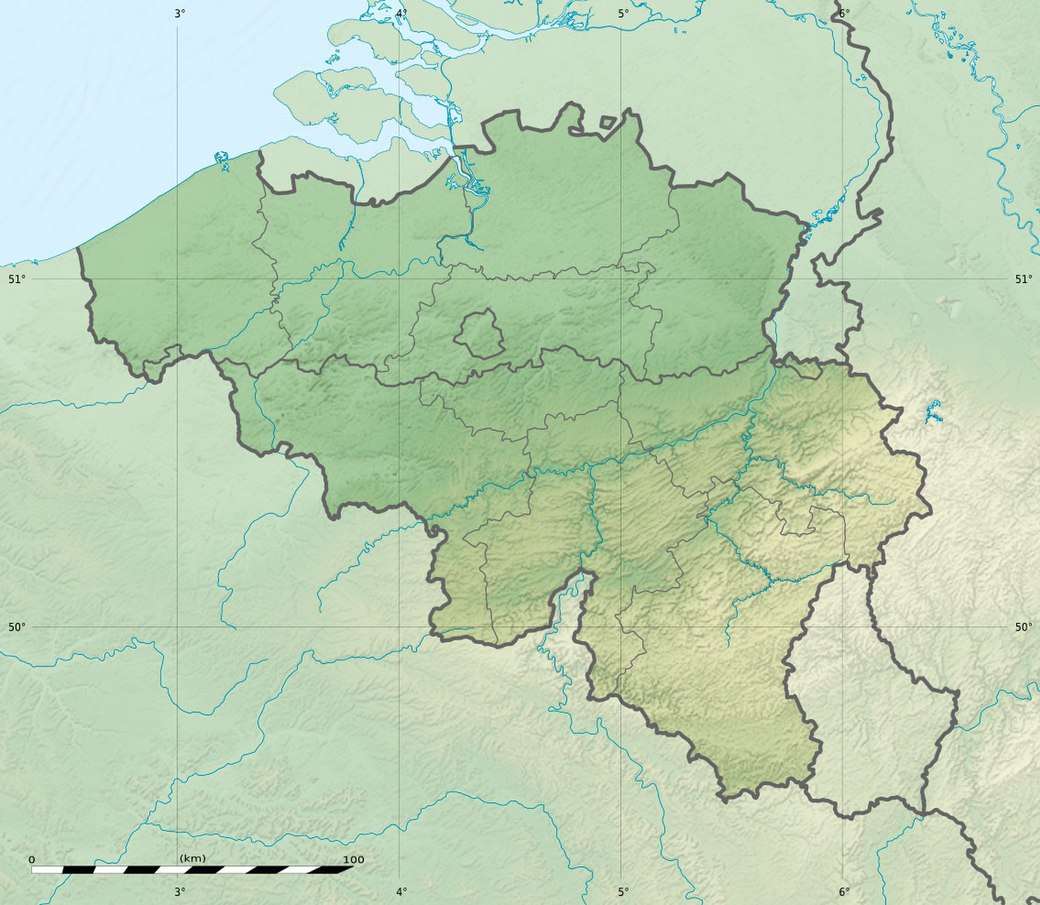

The Battle of Seneffe took place on 11 August 1674, during the 1672–1678 Franco-Dutch War near Seneffe in present-day Belgium. It was fought by a French army commanded by Louis II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé and a combined Dutch-Imperial-Spanish force led by William of Orange. While a clear French victory, both sides suffered heavy losses and it had little impact on the outcome of the war in the Low Countries.

| Battle of Seneffe | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Franco-Dutch War | |||||||

Battle of Seneffe, by Adam Frans van der Meulen | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

44,200 30,000 infantry 14,200 cavalry 60 guns |

62,000 40,000 infantry 22,000 cavalry ~70 guns[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

6,000 killed and wounded 4,000 captured |

8,600 killed and wounded 5,400 captured | ||||||

Seneffe was one of three battles in the Spanish Netherlands during the Franco-Dutch War and the only one unconnected to a siege, the dominant form of warfare in the late 17th century; Cassel in 1677 was an attempt to relieve Saint-Omer, while Saint-Denis in 1678 was fought to prevent the fall of Mons.

Background

In the 1667–1668 War of Devolution, France captured most of the Spanish Netherlands and Franche-Comté but relinquished the bulk of these gains in the 1668 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle with the Triple Alliance of the Dutch Republic, England and Sweden. Angered by what he viewed as ingratitude for previous French support, Louis XIV decided to attack the Dutch; he weakened his opponents by paying Sweden to remain neutral, and signing an alliance with England in the 1670 Treaty of Dover.[6]

In May 1672, French forces invaded the Dutch Republic and initially seemed to have achieved an overwhelming victory but by late July, the Dutch position had stabilised. Concern at French gains led to the August 1673 Treaty of the Hague between the Republic, Brandenburg-Prussia, Emperor Leopold and Charles II of Spain; in early 1674, Denmark joined the Alliance, while England and the Dutch made peace in the Treaty of Westminster.[7]

Forced into another war of attrition and with new fronts opening in Spain, Sicily and the Rhineland, French troops withdrew from the Dutch Republic by the end of 1673, retaining only Grave and Maastricht.[8] Louis now focused on retaking Spanish possessions gained in 1667–1668 but returned at Aix-La-Chappelle, a decision simplified by Spain's entry into the war.[9]

In early May, the French took the offensive in Franche-Comté, while Condé's army in the Spanish Netherlands remained on the defensive. The Allies besieged Grave in early July, which was too distant to have any realistic chance of being relieved by the French; with the advantage of superior numbers and aware of Louis' plans to capture Mons, the main Allied field army sought to take the initiative by invading French Flanders.[10]

The battle

The Spanish Netherlands was a compact area 160 kilometres wide, its highest point being only 100 metres above sea level; until the advent of railways in the 19th century, goods and supplies were largely transported by water and the region's commercial wealth was due to the large numbers of canals and rivers. Campaigning in this theatre largely focused on controlling access points to rivers such as the Lys, the Sambre and Meuse, while the flat terrain made possession of any high ground extremely advantageous.[11]

A Dutch-Spanish force under William of Orange and Count Monterrey, Governor of the Spanish Netherlands, spent June and July unsuccessfully attempting to bring Condé to battle. On 23 July, they were joined near Nivelles by an Imperial army led by a French Huguenot exile, the Comte de Souches, increasing their numbers to about 62,000. After the conclusion of operations in Franche-Comté, many of the troops used there were sent to join Condé, including his son the duc d'Enghien. By early August, his army of 44,200 was entrenched along the line of the Piéton river which joined the Sambre at Charleroi, then occupied by the French.[12]

Concluding these positions were too strong to be attacked from the direction of Nivelles, on 9 August the Allied army established a line between the villages of Arquennes to Roux, on the French left. They hoped to tempt Condé into an attack but he simply shifted his troops and the next day, William proposed moving around Seneffe and into the French rear.[12] This was supported by the Spanish, since it would cut Condé's supply lines and isolate the French garrison in Charleroi (see Map).[13]

At 4:00 am on 11 August, the Allied army set out split into three columns, each marching parallel to the French positions. The vanguard was commanded by the Comte de Souches, the rear by the Marquis d'Assentar, who had just replaced Monterrey as the senior Spanish officer, with William and the bulk of the infantry in the centre. The formation was dictated by the poor roads and resulted in gaps between the columns; recognising this vulnerability, a screening force of 6,000 cavalry under Prince Vaudémont was placed on the extreme left, passing close to Seneffe which the Allied troops would have to pass in order to move behind the French.[14]

Hearing the Allies were on the move, at 5:30 am Condé rode out to observe their dispositions and quickly perceived their intentions. The terrain they were crossing was largely marshy and broken up by numerous hedges, walls and woods, with limited exit points; gambling these factors would negate their superior numbers, Condé decided to attack. He sent 400 light cavalry under Saint Clar to skirmish with the Allied vanguard and slow down their march, while also despatching a cavalry brigade under the Marquis de Rannes to seize the high ground north of Seneffe.[15]

Around 10:00 am, de Rannes came into contact with Vaudémont, who asked William for infantry support; he was sent three battalions, which he placed near the bridge over the Zenne or Senne river that flowed through Seneffe, with his cavalry just behind.[16] Despite gout so severe he was unable to wear boots, Condé himself led the elite Maison du Roi cavalry across the Zenne above Seneffe and scattered Vaudémont's cavalry. Simultaneous assaults by de Rannes and Luxembourg overwhelmed the infantry, who were all either killed or taken prisoner.[17]

By midday, Condé had inflicted significant losses on the Allies and gained a clear, if minor victory. Instead of withdrawing, he continued and the battle became a series of confused and costly firefights, lasting until early evening.[18] After Vaudémont was driven out of Seneffe, William halted his march and formed a defensive line centred on the nearby Priory of St Nicolas, with the Marquis d'Assentar based in the hamlet of Fayt-la-Manage on his left. The Allied horse was once again driven from the field but the French were exhausted; the Dutch infantry remained intact, while the ground in front of their position was in any case unsuitable for cavalry.[19]

Against the advice of his senior officers, Condé committed his troops to a series of bloody frontal assaults, leading one himself, in which he was unhorsed and had to be rescued by his son, the Duc d'Enghien. Luxembourg destroyed much of the Dutch baggage train and despite heavy losses, the French finally over-ran the Allied positions at St Nicolas in the early evening. The two armies remained facing each other for the rest of the night and the next day, William made for Mons to re-equip while the French returned to their original positions on the Piéton.[20]

Casualties on all sides had been enormous, although the Imperial troops in the vanguard saw little combat, apart from minor skirmishing with Saint Clar's cavalry and William later accused de Souches of deliberately refusing to support him. While estimates vary, the consensus is that French losses were between 7,000 to 10,000 killed, wounded or captured, those of the Allies being a wider range of 8,000 – 15,000.[21]

Aftermath

.png)

Their losses shocked the French, one contemporary writing 'we have lost so much by this victory that without the Te Deum and captured flags at Notre Dame, we would believe we had lost the battle.'[22] The battle had little impact on the war; on 31 August, a large convoy arrived in the Allied camp outside Mons, bringing supplies, a month's pay in advance for the survivors and five new Dutch regiments. This made up for the losses suffered at Seneffe and William proposed they resume the invasion of France. [23]

Neither de Souches or Monterrey agreed to this and so the Allies compromised by besieging Oudenarde. Operations started on 16 September and Condé began marching to its relief on 19th; the Dutch and Spanish redoubled efforts to breach the walls before his arrival but without advising his allies, de Souches sent the Imperial artillery off to Ghent. His troops could not fight a battle without artillery and since the Dutch and Spanish could not face the French on their own, they were forced into a hasty retreat.[24]

After strong protests from the Dutch States General, de Souches was relieved of his command but this did little to solve the reality of diverging objectives in the Low Countries. De Souches' desire to minimise his own losses was driven by Imperial strategy, which was to prevent the French reinforcing Turenne in the Rhineland; the Spanish wanted to recover their losses in the Spanish Netherlands, a secondary objective for the Dutch, who now focused on retaking Grave and Maastricht.[25] On 9 October, William assumed command of the siege operations at Grave, which surrendered on 28th.[26]

Condé received an elaborate state reception at Versailles for Seneffe but his health was failing and the casualties had diminished Louis' trust in his abilities; he temporarily assumed command of French troops in the Rhineland following Turenne's death at Salzbach in July 1675 but retired before the end of the year. In the longer term, Seneffe confirmed Louis' preference for positional warfare, ushering in a period where siege and manoeuvre dominated military tactics.[27]

References

- Lynn, John (1996). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714 (Modern Wars In Perspective). Longman. pp. 80-81. ISBN 978-0582056299.

- De Périni, Hardÿ (1896). Batailles françaises, Volume V. Ernest Flammarion, Paris. p. 86.

- Lynn, p. 126

- Nimwegen 2010, p. 380.

- Bodart 1908, p. 95.

- Lynn, John (1996). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714 (Modern Wars In Perspective). Longman. pp. 109-110. ISBN 978-0582056299.

- Davenport, Frances (1917). "European Treaties bearing on the History of the United States and its Dependencies". p. 238. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Lynn 1999, p. 117.

- Young, 2004, p. 132.

- Lynn 1999, p. 125.

- Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688–1697: The Operations in the Low Countries (2013 ed.). Manchester University Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 0719089964.

- De Périni 1896, p. 82

- Lynn, p. 124

- De Hooge, Romeyn (1680). The Netherland-Historian Containing a True and Exact Relation of What Hath Passed in the Late Warrs (2018 ed.). Forgotten Books. pp. 499–500. ISBN 9780484752152. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Le 11 août 1674 – La bataille de Seneffe". Au fil des mots d'histoire. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- De Hooge, p. 499-500

- De Hooge, p. 501

- Lynn, p. 125

- De Périni 1896, p. 95-96

- De Périni 1896, p. 107

- Lynn, p. 125-126

- De Sévigné, Marie Rabutin-Chantal (author), De St-Germain, Pierre Marie Gault (ed) (1822–1823). Letters of Madame De Sévigné, Volume III; to the Count de Bussy, 5 September 1674. p. 353.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Van Nimwegen, Olaf (2010). The Dutch Army and the Military Revolutions, 1588–1688. Boydell Press. p. 479. ISBN 978-1843835752.

- Van Nimwegen 2010, p. 481.

- Anonymous (1744). The History of England, During the Reigns of K. William, Q. Anne and K George I, with an Introductory Review of the Reigns of the Royal Brothers Charles and James Stuart Volume 1. London: Daniel Brown. p. 263. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- Jacques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity through the Twenty-first Century, Volume 2, F-O. Greenwood. p. 408. ISBN 978-0313335389.

- Lynn, p. 125

Sources

- Anonymous (1744). The History of England, During the Reigns of K. William, Q. Anne and K George I, with an Introductory Review of the Reigns of the Royal Brothers Charles and James, Volume 1. London: Daniel Brown.;

- Bodart, G. (1908). Militär-historisches Kriegs-Lexikon (1618–1905).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688–1697: The Operations in the Low Countries. MUP. ISBN 0719089964.;

- De Hooge, Romeyn (1680). The Netherland-Historian Containing a True and Exact Relation of What Hath Passed in the Late Warrs. Forgotten Books 2018. ISBN 0719089964.;

- De Perini, Hardÿ (1896). Batailles françaises, Volume V. Paris: Ernest Flammarion.;

- De Sévigné, Marie Rabutin-Chantal (author), De St-Germain, Pierre Marie Gault (ed) (1822–1823). Letters of Madame De Sévigné, Volume III; to the Count de Bussy, 5 September 1674. Paris.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link);

- Lynn, John (1996). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714 (Modern Wars In Perspective). Longman. ISBN 978-0582056299.;

- Nimwegen, Olaf van (2010). The Dutch Army and the Military Revolutions, 1588-1688. Translated by May, Andrew. The Boydell Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Rhea (1965). Spain; A Modern History. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472071500.

- Young, William (2004). International Politics and Warfare in the Age of Louis XIV and Peter the Great. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0595329922.