Battle of Mulhouse (1674)

The Battle of Mulhouse occurred on December 29, 1674, during the Franco-Dutch War between the French army and troops of the Holy Roman Empire and its allies, as part of Turenne's Winter Campaign. The French army was commanded by the Vicomte de Turenne and the imperial army was led by Prince Alexandre-Hippolyte de Bournonville.[1]

| Battle of Mulhouse | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Franco-Dutch War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,000 | 5,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 60 killed, wounded or captured |

1,300 300 killed 1,000 captured | ||||||

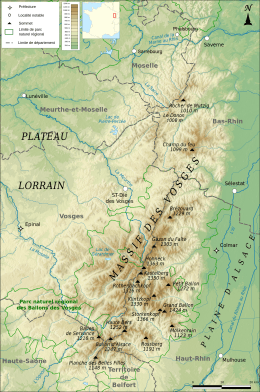

While the imperial armies were in their winter quarters, Turenne split up his army and traveled through the Vosges mountains before reforming it near Belfort.[1] This helped confuse his enemy and gave his troops a surprise advantage over his opponents in Mulhouse on December 29, leading to French victory.

Background

During the 1667-1668 War of Devolution, France captured most of the Spanish Netherlands but under the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, it was forced to relinquish most of these gains by the Triple Alliance between the Dutch Republic, England and Sweden.[2]

Louis XIV now moved to break up the Alliance before making another attempt on the Spanish Netherlands. In return for large subsidies, Sweden would remain neutral but also attack its regional rival, Brandenburg-Prussia if it attempted to intervene. In 1670, Charles II of England signed the Treaty of Dover, agreeing to an alliance with France against the Dutch, and the provision of 6,000 English and Scottish troops for the French army.[3] It contained a number of secret provisions, not revealed until 1771, one being the payment by Louis to Charles of £230,000 per year for the services of this Brigade.[4]

When France invaded the Dutch Republic in May 1672, it seemed at first that they had achieved an overwhelming victory. However, by July the Dutch position had stabilised, while concern at French gains brought them support from Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia, Emperor Leopold and Charles II of Spain.[5] In August 1672, an Imperial army entered the Rhineland and Louis was forced into another war of attrition around the French frontiers.[6]

The French army in Germany was led by Turenne, (1611-1675), considered the greatest general of the period.[7] Over the next two years, he won a series of victories over superior Imperial forces led by Alexander von Bournonville and Raimondo Montecuccoli, the one commander contemporaries considered his equal.[8] After 1673, it became a largely defensive campaign, focused on protecting French gains in the Rhineland and preventing Imperial forces linking up with the Dutch. France was over-extended, a problem that increased when Denmark joined the Alliance in January, 1674, while England and the Dutch Republic made peace in the February Treaty of Westminster.[9]

Although the main campaign of 1674 was fought in Flanders, an Imperial army opened a second front in Alsace.[10] In September, Bournonville was allowed to cross the Rhine at Strasbourg, with over 40,000 men, a diplomatic coup for Emperor Leopold; despite being a Free Imperial city and technically part of the Holy Roman Empire, the city had previously been neutral and its bridge was a major crossing point. Bournonville now halted, waiting for another 20,000 men provided by Frederick William; once combined, they would overwhelm the smaller French army and invade eastern France.[11]

The campaign that began in June 1674 and ended with his death in July 1675 has been described as 'Turenne's most brilliant campaign.'[12] Despite being out-numbered, he attacked Bournonville on 4 October; the Battle of Entzheim was indecisive but Bournonville withdrew, entering winter quarters around Colmar, where he was reinforced by Frederick William's troops.[13]

It was normal practice at this time to avoid active campaigning during the winter, but Turenne now went on the offensive. He took his forces south, using the Vosges mountains and various deceptions to screen his movements from the Imperial commanders; on 27 December, he reached Belfort, at the southern end of the Vosges.[14]

Battle

Turenne's arrival at Belfort took Bournonville by surprise; he hoped to take advantage of this by a prompt attack into Alsace, but the need to gather food forced the main French army to halt. Interrogation of prisoners told Turenne that the Imperial forces and their allies had orders to concentrate in two groupings, one at Colmar and the other at Altkirch. Turenne determined to force his way between the two groups by advancing through Mulhouse, then a free city associated with Switzerland. He could take with him only 3,000 cavalry. A small force of infantry was to follow as rapidly as practicable.[15]

Bournonville hoped to hold the line of the Ill River to gain time for his army to fully assemble. The delay in the French advance allowed an enemy vanguard to occupy Mulhouse before Turenne arrived. This was part of a cavalry detachment of over 5,000 men that was marching north from Altkirch toward Colmar under the command of Margrave Hermann of Baden-Baden. This cavalry included men of Austria, Baden, and Munster. As soon as Turenne's small force reached the Ill near Mulhouse on December 29, he ordered Marechal de Camp Rene de la Tour, Marquis de Montauban, to reconnoiter the enemy position with two squadrons of French cavalry. Turenne followed and, when he rejoined Montauban, they saw two enemy squadrons posted near the river and five more squadrons in support nearby.[16]

As the river was fordable at this point, Turenne ordered Montauban to attack the foremost enemy squadrons. The battle quickly escalated as Turenne and the enemy commanders sent in reinforcements. Turenne deployed a particularly large force on his right flank, giving the impression that the whole French army was arriving. The French cavalry advanced with as much fanfare as possible, with trumpets blaring and cymbals crashing. Suddenly, the cuirassiers of the Emperor turned and fled into Mulhouse. This led the whole enemy force to withdraw in disorder in several directions; some fled toward Basel to take refuge in Switzerland. Turenne had lost 60 men, including Montauban who had been captured. Sources disagree on the enemy's losses, but the casualties appear to have numbered at least 300.[17]

Aftermath

Turenne returned to his main force at Belfort. The French army was finally ready to resume its advance in the first days of January. Turenne now marched on the enemy headquarters at Colmar. Nearby, he would win a decisive victory at the Battle of Turckheim that would force the Imperial army out of Alsace.[18]

Mulhouse has grown into a city of over 100,000. As a result, the fields and fords of the 1674 battlefield largely have been obscured by cityscape.[19]

See also

Notes

- Tucker, Spencer (2009). A global chronology of conflict: From the ancient world to the modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 651. ISBN 978-1-85109-667-1.

- Lynn, John (1996). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667-1714 (Modern Wars In Perspective). Longman. p. 109. ISBN 978-0582056299.

- Lynn 1999, p. 109-110.

- J. P. Kenyon, The History Men. The Historical Profession in England since the Renaissance. Second Edition (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1993), pp. 67-68.

- Smith, Rhea (1965). Spain; A Modern History. University of Michigan Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-0472071500.

- Lynn 1999, p. 117.

- "Turenne 1611-1675". Musée virtuel du Protestantisme. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- Guthrie, William (2003). The Later Thirty Years War: From the Battle of Wittstock to the Treaty of Westphalia (Contributions in Military Studies). Praeger. p. 239. ISBN 978-0313324086.

- Davenport, Frances (1917). "European Treaties bearing on the History of the United States and its Dependencies". p. 238. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Chandler, 1980, 40.

- Chandler, 1984, 7; Lynn, 1999, 110-111, 131.

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2008). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1494-2007. McFarland & Co;. p. 46. ISBN 978-0786433193.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- David Chandler, Marlborough as Military Commander (Staplehurst, Kent: Spellmount, 1984), 7; Lynn, The Wars of Louis XIV, 110-111, 131.

- Richard Brooks, ed., Atlas of World Military History (New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2000), 84; Lynn, The Wars of Louis XIV, 132-133.

- Theodore Ayrault Dodge, Gustavus Adolphus: A History of the Art of War from its Revival After the Middle Ages to the End of the Spanish Succession War, with a Detailed Account of the Campaigns of the Great Swede, and of the Most Famous Campaigns of Turenne, Conde, Eugene, and Marlborough (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1890), II: 628-29; A Relation or Journal of the Campaigns of the Marechal de Turenne, in the Years One Thousand Six Hundred Seventy Four, and One Thousand Six Hundred Seventy Five; 'Til the Time of His Death. Done from the French, By an Officer of the Army (Dublin: Addison's Head, 1732), 69; Hardy de Perini, Batailles Francaises, 5e Serie (Paris: Ernest Flammarion, 1894-1906), V: 132.

- Dodge, Gustavus Adolphus, II: 629; A Relation or Journal, 69; Anselme de Sainte Marie, Histoire Genealogique et Chronologique de la Maison de France, (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1879), 9.2: 63.

- Dodge, Gustavus Adolphus, II: 629; A Relation or Journal, 69; de Perini, Batailles Francaises, V: 133-134. Dodge reports 300 men lost, whereas de Perini lists 300 dead and 1,000 taken prisoner; the latter figures seem inflated for a relatively small engagement.

- Dodge, Gustavus Adolphus, II: 628; A Relation or Journal, 68.

- http://www.mulhouse.fr/fr/mulhouse-en-chiffres Archived 2015-09-03 at the Wayback Machine (accessed September 18, 2015).

References

- Brooks, Richard, ed. Atlas of World Military History. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2000.

- Chandler, David. Atlas of Military Strategy. New York: the Free Press, 1980.

- Chandler, David. Marlborough as Military Commander. Staplehurst, Kent: Spellmount, 1984.

- De Perini, Hardy. Batailles Francaises, Series 5, Vol. V. Paris: Ernest Flammarion, 1894-1906.

- De Sainte Marie, Anselme, Histoire Genealogique et Chronologique de la Maison de France, Vol. 9, Part 2. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1879.

- Dodge,Theodore Ayrault. Gustavus Adolphus: A History of the Art of War from its Revival After the Middle Ages to the End of the Spanish Succession War, with a Detailed Account of the Campaigns of the Great Swede, and of the Most Famous Campaigns of Turenne, Conde, Eugene, and Marlborough, Vol II. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1890.

- Lynn, John. The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667-1714. London, New York: Longman, 1999.

- A Relation or Journal of the Campaigns of the Marechal de Turenne, in the Years One Thousand Six Hundred Seventy Four, and One Thousand Six Hundred Seventy Five; 'Til the Time of His Death. Done from the French, By an Officer of the Army. Dublin: Addison's Head, 1732.

- Tucker, Spencer (2009). A global chronology of conflict: From the ancient world to the modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO., 651. ISBN 1-85109-667-1.