Einstein refrigerator

The Einstein–Szilard or Einstein refrigerator is an absorption refrigerator which has no moving parts, operates at constant pressure, and requires only a heat source to operate. It was jointly invented in 1926 by Albert Einstein and his former student Leó Szilárd, who patented it in the U.S. on November 11, 1930 (U.S. Patent 1,781,541). The three working fluids in this design are water, ammonia and butane.[1] The Einstein refrigerator is a development of the original three-fluid patent by the Swedish inventors Baltzar von Platen and Carl Munters.

| Thermodynamics | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

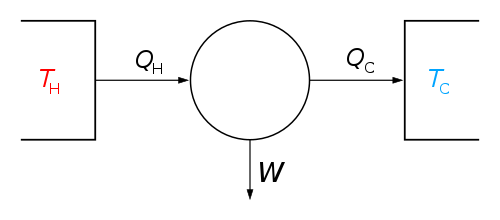

The classical Carnot heat engine | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

History

From 1926 until 1934 Einstein and Szilárd collaborated on ways to improve home refrigeration technology. The two were motivated by contemporary newspaper reports of a Berlin family who had been killed when a seal in their refrigerator failed and leaked toxic fumes into their home. Einstein and Szilárd proposed that a device without moving parts would eliminate the potential for seal failure, and explored practical applications for different refrigeration cycles. Einstein used the experience he had gained during his years at the Swiss Patent Office to apply for valid patents for their inventions in several countries. The two were eventually granted 45 patents in their names for three different models.

It has been suggested that most of the actual inventing was performed by Szilárd, with Einstein merely acting as a consultant and helping with the patent-related paperwork,[2] but others assert Einstein labored over the project.[3]

The refrigerator was not immediately put into commercial production; the most promising of their patents being quickly bought up by the Swedish company Electrolux. Einstein and Szilard earned $750 (the equivalent of $10,000 in 2017).[3] A few demonstration units were constructed from other patents.

In 2007, a prototype of a commercial refrigeration device intended for use as a vaccine cooler was shown by Adam Grosser at a TED Talk;[4] the prototype operates at constant pressure, requiring exposure to a cooking fire to activate it. Once heated, the prototype would serve as a refrigerator for 24 hours. As of 2019, Grosser's prototype has not yet been put into commercial production .

In 2008, electrical engineers at Oxford University's Energy and Power Group, part of the university's Department of Engineering Science,[5] revived the Einstein refrigerator as an attempt to produce a no-electricity refrigerator suitable for use in rural areas.[1] The group, led by Malcolm McCulloch noted that the design was still "far from being commercialized",[1] but might allow the efficiency of the original Einstein-Szilárd design to be quadrupled.[6]

See also

- Rudolf Goldschmidt (for the Einstein–Goldschmidt hearing aid)

- Icyball

- Timeline of low-temperature technology

Notes

- "Einstein's Refrigerator Using No Electricity/No Freon Revived at Oxford". The Green Optimistic. 6 February 2015.

- Dannen, Geene (1997), "The Einstein–Szilard Refrigerators", Scientific American, 276 (1): 90–95, Bibcode:1997SciAm.276a..90D, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0197-90, archived from the original on 2013-02-01

- Kean, Sam (2017). Caesar's Last Breath. New York: Hachette. ISBN 9780316381635. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- Grosser, Adam (2007). "A mobile fridge for vaccines". TED.

- "Malcolm McCulloch". Affordable Energy for Humanity (AE4H). University of Waterloo. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Alok, Jha (21 September 2008). "Einstein fridge design can help global cooling". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

References

- Einstein, A., L. Szilárd, "Refrigeration" (Appl: 16 December 1927; Priority: Germany, 16 December 1926) U.S. Patent 1,781,541, 11 November 1930.

- Einstein, A., L. Szilárd, "Accompanying notes and remarks for Pat. No. 1,781,541". Mandeville Special Collections Library USC. Box 35, Folder 3, 1927; 52 pages.

- Einstein, A., L. Szilárd, "Improvements Relating to Refrigerating Apparatus." (Appl: 16 December. 1927; Priority: Germany, 16 December 1926). Patent Number 282,428 (United Kingdom). Complete accept.: 5 November 1928.

External links

- Flanigan, Allen, " (German site) Wolfgang Engels from the University Oldenburg rebuilt the original concept— the housing is manufactured out of concrete, i.e. the total mass of the completed apparatus is around 400 kg with 20 kg of alcohol in the refrigeration cycle. The project was completed in 2005.

- Patent document US1781541 (European Patent Office)

- Patent document GB282428 (European Patent Office)

- How kerosene refrigerators work. Archived version of page.