Tea leaf paradox

The tea leaf paradox is a phenomenon where tea leaves in a cup of tea migrate to the center and bottom of the cup after being stirred rather than being forced to the edges of the cup, as would be expected in a spiral centrifuge. The correct physical explanation of the paradox was for the first time given by James Thomson in 1857. He correctly connected the appearance of secondary flow (in both Earth atmosphere and tea cup) with ″friction on the bottom″.[2] The formation of secondary flows in an annular channel was theoretically treated by Boussinesq as early as in 1868.[3] The migration of near-bottom particles in river-bend flows was experimentally investigated by A. Ya. Milovich in 1913.[1] The solution first came from Albert Einstein in a 1926 paper in which he explained the erosion of river banks, and repudiated Baer's law.[4][5]

.jpg)

Explanation

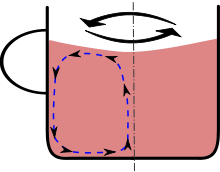

Stirring the liquid causes a spiral flow schema by centrifugal action. As such, the anticipation is that tea leaves would, because of their mass, move to the edge of the cup. However, friction between moving water and the cup increases water pressure, resulting in a high pressure boundary layer. This increase in pressure extends inwards and exceeds the mass of the tea leaves' inertia, which move outward by centrifugal action. Friction therefore produces a centripetal force upon the mass of tea leaves.

This boundary layer causes a secondary flow schema, ultimately resulting in a spiral. The primary flow schema, caused by the stirring, forces water outward and up the edge of the cup. Then, under increasing pressure, water moves downward, inward and then upward, about the centre (see diagram). In this way, the secondary flow schema exerts an inward force upon the mass of the tea leaves (which exceeds their mass), which effectively contains their outward tendency, and causes the observable paradox.

Incidentally, the circular movement of water is slower at the bottom of the cup than at the top, because the friction surface at the bottom is greater. This difference 'twists' the moving body of water into a spiral.

Applications

The phenomenon has been used to develop a new technique to separate red blood cells from blood plasma,[6][7] to understand atmospheric pressure systems,[8] and in the process of brewing beer to separate out coagulated trub in the whirlpool.[9]

See also

- Baer's law

- Ekman layer

- Secondary flow

References

- His results are cited in: Joukovsky N.E. (1914). "On the motion of water at a turn of a river". Matematicheskii Sbornik. 28. Reprinted in: Collected works. 4. Moscow; Leningrad. 1937. pp. 193–216, 231–233 (abstract in English).

- James Thomson, On the grand currents of atmospheric circulation (1857). Collected Papers in Physics and Engineering, Cambridge Univ., 1912, 144-148 djvu file

- Boussinesq J. (1868). "Mémoire sur l'influence des frottements dans les mouvements réguliers des fluides" (PDF). Journal de mathématiques pures et appliquées 2 e série. 13: 377–424.

- Bowker, Kent A. (1988). "Albert Einstein and Meandering Rivers". Earth Science History. 1 (1). Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- Einstein, Albert (March 1926). "Die Ursache der Mäanderbildung der Flußläufe und des sogenannten Baerschen Gesetzes". Die Naturwissenschaften. Berlin / Heidelberg: Springer. 14 (11): 223–4. Bibcode:1926NW.....14..223E. doi:10.1007/BF01510300. English translation: The Cause of the Formation of Meanders in the Courses of Rivers and of the So-Called Baer’s Law, accessed 2017-12-12.

- Arifin, Dian R.; Leslie Y Yeo; James R. Friend (20 December 2006). "Microfluidic blood plasma separation via bulk electrohydrodynamic flows". Biomicrofluidics. American Institute of Physics. 1 (1): 014103 (CID). doi:10.1063/1.2409629. PMC 2709949. PMID 19693352. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 2008-12-28. Lay summary – Science Daily (January 17, 2007).

- Pincock, Stephen (17 January 2007). "Einstein's tea-leaves inspire new gadget". ABC Online. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- Tandon, Amit; Marshall, John. "Einstein's Tea Leaves and Pressure Systems in the Atmosphere". Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- Bamforth, Charles W. (2003). Beer: tap into the art and science of brewing (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-19-515479-5.

External links

- Highfield, Roger (14 January 2008). "Dr Roger's Home Experiments". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- Sethi, Ricky J. (September 30, 1997). "Why do particles move towards the center of the cup instead of outer rim?". MadSci Network. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- Booker, John R. "Student Notes - Physics of Fluids - ESS 514/414" (PDF). Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of Washington. ch. 5.8 p. 48. Retrieved 2008-12-29. See also figure 25 in figures.pdf

- Stubley, Gordon D. (May 31, 2001). "Mysteries of Engineering Fluid Mechanics" (PDF). Mechanical Engineering Department, University of Waterloo. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 6, 2009. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- Einstein's 1926 article online and analyzed on BibNum (click 'Télécharger' for English) (unsecure link).