Economy of Latvia

The economy of Latvia is an open economy in Northern Europe and is part of the European Union's (EU) single market. Latvia is a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) since 1999,[23] a member of the European Union since 2004, a member of the Eurozone since 2014 and a member of the OECD since 2016.[24] Latvia is ranked the 14th in the world by the Ease of Doing Business Index prepared by the World Bank Group,[25] According to the Human Development Report 2011, Latvia belongs to the group of very high human development countries.[26] Due to its geographical location, transit services are highly developed, along with timber and wood-processing, agriculture and food products, and manufacturing of machinery and electronic devices.

| Currency | Euro (EUR, €) |

|---|---|

| Calendar year | |

Trade organisations | EU, OECD and WTO |

Country group | |

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

Population below poverty line | |

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment | |

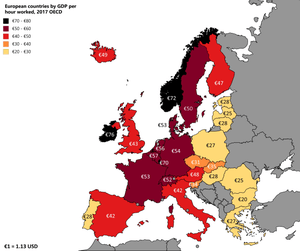

Average gross salary | €1,089 / $1,215 monthly (June, 2019) |

Average net salary | €806 / $900 monthly (June, 2019) |

Main industries | processed foods, processed wood products, textiles, processed metals, pharmaceuticals, railroad cars, synthetic fibers, electronics |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods | foodstuffs, wood and wood products, metals, machinery and equipment, textiles |

Main export partners | |

| Imports | |

Import goods | machinery and equipment, consumer goods, chemicals, fuels, vehicles |

Main import partners | |

FDI stock | |

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| Revenues | 38.7% of GDP (2019)[16] |

| Expenses | 38.9% of GDP (2019)[16] |

| Economic aid | recipient: $0.1 billion (1995) |

Foreign reserves | |

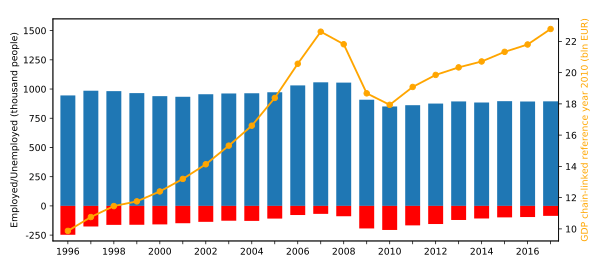

Latvia's economy has had rapid GDP growth of more than 10% per year during 2006–07, but entered a severe recession in 2009 as a result of an unsustainable current account deficit, collapse of the real estate market, and large debt exposure amid the softening world economy. Triggered by the collapse of Parex Bank, the second largest bank, GDP decreased by almost 18% in 2009,[27] and the European Union, the International Monetary Fund, and other international donors provided substantial financial assistance to Latvia as part of an agreement to defend the currency's peg to the euro in exchange for the government's commitment to stringent austerity measures. In 2011 Latvia achieved GDP growth by 5.5%[28] and thus Latvia again was among the fastest growing economies in the European Union. The IMF/EU program successfully concluded in December 2011.[29]

Privatization is mostly complete, except for some of the large state-owned utilities. Export growth contributed to the economic recovery, however, the bulk of the country's economic activity is in the services sector.

Economic history

For centuries under Hanseatic and German influence and then during its inter-war independence, Latvia used its geographic location as an important East-West commercial and trading centre. Industry served local markets, while timber, paper and agricultural products were Latvia's main exports. Conversely, years in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union tended to integrate Latvia's economy with their markets and also serve those countries' large internal industrial needs.

After reestablishing its independence, Latvia proceeded with market-oriented reforms, albeit at a measured pace. Its freely traded currency, the lat, was introduced in 1993 and held steady, or appreciated, against major world currencies. Inflation was reduced from 958.6% in 1992 to 25% by 1995 and 1.4% by 2002.

After contracting substantially between 1991–95, the economy steadied in late 1994, led by a recovery in light industry and a boom in commerce and finance. This recovery was interrupted twice, first by a banking crisis and the bankruptcy of Banka Baltija, Latvia's largest bank, in 1995 and second by a severe crisis in the financial system of neighbouring Russia in 1998. After 2000, Latvian GDP grew by 6–8% a year for 4 consecutive years. Latvia's state budget was balanced in 1997 but the 1998 Russian financial crisis resulted in large deficits, which were reduced from 4% of GDP in 1999 to 1.8% in 2003. These deficits were smaller than in most of the other countries joining the European Union in 2004.

Until the middle of 2008, Latvia had the fastest developing economy in Europe. In 2003, GDP growth was 7.5% and inflation was 2.9%. The centrally planned system of the Soviet period was replaced with a structure based on free-market principles. In 2005, private sector share in GDP was 70%.[30] Recovery in light industry and Riga's emergence as a regional financial and commercial centre offset shrinkage of the state-owned industrial sector and agriculture. The official unemployment figure was held steady in the 7%–10% range.

Economic contraction in 2008–2010

The financial crisis of 2007–2008 severely disrupted the Latvian economy, primarily as a result of the easy credit bubble that began building up during 2004. The bubble burst leading to a rapidly weakening economy, resulting in a budget, wage and unemployment crisis.[31] Latvia had the worst economic performance in 2009, with annual growth rate averaging −18%.

The Latvian economy entered a phase of fiscal contraction during the second half of 2008 after an extended period of credit-based speculation and unrealistic inflation of real estate values. The national account deficit for 2007, for example, represented more than 22% of the GDP for the year while inflation was running at 10%.[32] By 2009 unemployment rose to 23% and was the highest in the EU.[33]

Paul Krugman, the Nobel Laureate in economics for 2008, wrote in his New York Times Op-Ed column for 15 December 2008:

"The acutest problems are on Europe's periphery, where many smaller economies are experiencing crises strongly reminiscent of past crises in Latin America and Asia: Latvia is the new Argentina".[34]

By August 2009, Latvia's GDP had fallen by 20% year on year, with Standard & Poor's predicting a further 16% contraction to come. The International Monetary Fund suggested a devaluation of Latvia's currency, but the European Union objected to this, on the grounds that the majority of Latvia's debt was denominated in foreign currencies.[35] Financial economist Michael Hudson has advocated for redenominating foreign currency liabilities in Latvian lats before devaluing.

However, by 2010 there were indications that Latvia's policy of internal devaluation was successful.[36]

Economic recovery 2010–2012

The economic situation has since 2010 improved,[37] and by 2012 Latvia was described as a success by IMF managing director Christine Lagarde[38] showing strong growth forecasts. The Latvian economy grew by 5.5% in 2011[39] and by 5.6% in 2012 reaching the highest rate of growth in Europe.[40] Unemployment, however, remains high, and GDP remains below the pre-crisis level.[41]

Privatisation

Privatisation in Latvia is almost complete. Virtually all of the previously state-owned small and medium companies have been privatized, leaving only a small number of politically sensitive large state companies. In particular, the country's main energy and utility company, Latvenergo remains state-owned and there are no plans to privatize it. The government also holds minority shares in Ventspils Nafta oil transit company and the country's main telecom company Lattelecom but it plans to relinquish its shares in the near future.

Foreign investment in Latvia is still modest compared with the levels in north-central Europe. A law expanding the scope for selling land, including land sales to foreigners, was passed in 1997. Representing 10.2% of Latvia's total foreign direct investment, American companies invested $127 million in 1999. In the same year, the United States exported $58.2 million of goods and services to Latvia and imported $87.9 million. Eager to join Western economic institutions like the World Trade Organization, OECD, and the European Union, Latvia signed a Europe Agreement with the EU in 1995 with a 4-year transition period. Latvia and the United States have signed treaties on investment, trade, and intellectual property protection and avoidance of double taxation.

Employment

Average wages are higher in Riga and its surroundings and in Ventspils and its surroundings, with inland border regions lacking behind, mainly the region of Latgale.

Energy

Almost all of Latvian electricity is produced with Hydroelectricity. Biggest hydroelectric power stations are Pļaviņas Hydroelectric Power Station, Riga Hydroelectric Power Plant, Ķegums Hydroelectric Power Station.

In 2017 about 4381 GWh were produced in hydro power and 150 GWh in wind power. There is a steady increase in Wind electricity production, and by 2022 the biggest wind farm is supposed to open which would produce 0.7 terawatt hours of energy (10% of country total)[42]

Latvia imports 100% of its natural gas from Russia.[43]

Tourism

Statistics

Household income or consumption by percentage share:

lowest 10%:

2.9%

highest 10%:

25.9% (1998)

Industries: synthetic fibres, agricultural machinery, fertilizers, radios, electronics, pharmaceuticals, processed foods, textiles, timber; note – dependent on imports for energy and raw materials

Industrial production growth rate: 8.5% (2004 est.)

Electricity – production: 4,547 GWh (2002)

Electricity – production by source:

fossil fuel:

29.1%

hydro:

70.9%

nuclear:

0%

other:

0% (2001)

Electricity – consumption: 5,829 GWh (2002)

Electricity – exports: 1,100 GWh (2002)

Electricity – imports: 2,700 GWh (2002)

Agriculture – products: wheat, barley, potatoes, vegetables; beef, milk, eggs; fish

Foreign direct investments in Latvia: Lursoft statistics on the remaining amount of investments at the end of each year.

Packet of 20 cigarettes: On Average 3.30 – 4.50 EUR.

References

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Population on 1 January". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2020". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "CIA World Factbook". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "People at risk of poverty or social exclusion". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Labor force, total - Latvia". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Employment rate by sex, age group 20-64". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- "Unemployment by sex and age - monthly average". appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "Youth unemployment rate". data.oecd.org. OECD. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- "Ease of Doing Business in Latvia". Doingbusiness.org. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- "Euro area and EU27 government deficit both at 0.6% of GDP" (PDF). ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Sovereigns rating list". Standard & Poor's. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- Rogers, Simon; Sedghi, Ami (15 April 2011). "How Fitch, Moody's and S&P rate each country's credit rating". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- "Rating Action: Moody's upgrades Latvia's government bond ratings to A3; stable outlook". Moody's. 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "Fitch Affirms Latvia at 'A-'; Outlook Stable". Fitch. 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "Scope affirms Latvia's credit rating of A-, Outlook remains Stable". Scope Ratings. 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- https://data.oecd.org/lprdty/gdp-per-hour-worked.htm#indicator-chart

- "Members and Observers".

- "Latvia becomes full-fledged OECD member". LETA. 1 July 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- "Rankings – Doing Business – The World Bank Group". Doing Business. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- Human Development Index and its components Retrieved 2012-09-06

- The CIA World Factbook Latvia – CIA – The World Factbook Retrieved 2012-09-06

- "GDP of Latvia increased by 5.5% in 2011". The Baltic Course. 9 March 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- Latvia and the Baltics—a Story of Recovery by Christine Lagarde managing director, International Monetary Fund Riga, 5 June 2012

- Ruta Aidis, Friederike Welter: The Cutting Edge: Innovation and Entrepreneurship in New Europe, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2008, p. 32

- Damien, McGuinness (4 February 2010). "In Pictures: Latvia economy reels in recession". BBC.

- "Latvia". CIA. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- "Robin Hood hacker exposes bankers". BBC News. 24 February 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Krugman, Paul (15 December 2008). "European Crass Warfare". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose (10 August 2009). "S&P downgrades Baltic states' debt ratings". The Daily Telegraph.

- Baltic Business News, 8 February 2010

- Moody's: Latvian economy is stabilizing Baltic Business News, Retrieved on 3 September 2012

- Those who change will endure – IMF managing director LETA Retrieved on 5 June 2012

- Danske Bank: we expect Latvian GDP to grow by 2.0% y/y in 2012 Retrieved on 3 September 2012

- GDP growth in Latvia, at 5.6%, the fastest in Europe; growth to moderate this year Archived 22 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.multpl.com/latvia-real-gdp

- "Par aptuveni 250 miljoniem eiro būvēs Latvijā lielāko vēja parku". www.lsm.lv (in Latvian). Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- "Europe's Declining Gas Demand: Trends and Facts about European Gas Consumption - June 2015". (PDF). p.9. E3G. Source: Eurostat, Eurogas, E3G.

External links

- Latvia's Tiger Economy Loses Its Bite by Kristina Rizga, The Nation, 28 October 2009

- Latvia's Internal Devaluation: A Success Story?, from the Center for Economic and Policy Research, December 2011

- European Commission's DG ECFIN's country page on Latvia.

- World Bank Summary Trade Statistics 2012

.svg.png)