Dakota War of 1862

The Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising, the Dakota Uprising, the Sioux Outbreak of 1862, the Dakota Conflict, the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862 or Little Crow's War, was an armed conflict between the United States and several bands of Dakota (also known as the eastern 'Sioux'). It began on August 17, 1862, along the Minnesota River in southwest Minnesota, four years after its admission as a state. Throughout the late 1850s in the lead-up to the war, treaty violations by the United States and late or unfair annuity payments by Indian agents caused increasing hunger and hardship among the Dakota. During the war, the Dakota made extensive attacks on hundreds of settlers and immigrants, which resulted in settler deaths, and caused many to flee the area. Intense desire for immediate revenge ended with soldiers capturing hundreds of Dakota men and interning their families. A military tribunal quickly tried the men, sentencing 303 to death for their crimes. President Lincoln would later commute the sentence of 264 of them. The mass hanging of 38 Dakota men was conducted on December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota; it was the largest mass execution in United States history.

| Dakota War of 1862 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Sioux Wars and the American Civil War | |||||||

1904 painting "Attack on New Ulm" by Anton Gag | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Dakota | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Little Crow Wabasha Big Eagle Shakopee | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

77 soldiers 450–800 civilians[1] | 150 dead, 38 executed[2]+2 executed November 11, 1865 | ||||||

Traders with the Dakota previously had demanded that the government give the annuity payments directly to them (introducing the possibility of unfair dealing between the agents and the traders to the exclusion of the Dakota). In mid-1862, the Dakota demanded the annuities directly from their agent, Thomas J. Galbraith. The traders refused to provide any more supplies on credit under those conditions, and negotiations reached an impasse.[3]

On August 17, 1862, one young Dakota with a hunting party of three others killed five settlers while on a hunting expedition. That night a council of Dakota decided to attack settlements throughout the Minnesota River valley to try to drive whites out of the area. There has never been an official report on the number of settlers killed, although in President Abraham Lincoln's second annual address, he said that no fewer than 800 men, women, and children had died.

Over the next several months, continued battles of the Dakota against settlers and later, the United States Army, ended with the surrender of most of the Dakota bands.[4] By late December 1862, US soldiers had taken captive more than a thousand Dakota, including women, children and elderly men in addition to warriors, who were interned in jails in Minnesota. After trials and sentencing by a military court, 38 Dakota men were hanged on December 26, 1862 in Mankato in the largest one-day mass execution in American history. In April 1863, the rest of the Dakota were expelled from Minnesota to Nebraska and South Dakota. The United States Congress abolished their reservations. Additionally, the Ho-Chunk people living on reservation lands near Mankato were expelled from Minnesota as a result of the war.

Background

Previous treaties

The United States and Dakota leaders negotiated the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux[5] on July 23, 1851, and Treaty of Mendota on August 5, 1851, by which the Dakota ceded large tracts of land in Minnesota Territory to the U.S. in exchange for promises of money and goods. From that time on, the Dakota were to live on a 20-mile (32 km) wide Indian reservation centered on a 150 mile (240 km) stretch of the upper Minnesota River.

However, the United States Senate deleted Article 3 of each treaty, which set out reservations, during the ratification process. Much of the promised compensation never arrived, was lost, or was effectively stolen due to corruption in the Bureau of Indian Affairs (then called the Office of Indian Affairs). Also, annuity payments guaranteed to the Dakota often were provided directly to traders instead (to pay off debts the Dakota incurred to the traders).

Encroachments on Dakota lands

When Minnesota became a state on May 11, 1858, representatives of several Dakota bands led by Little Crow traveled to Washington, D.C., to negotiate about enforcing existing treaties. The northern half of the reservation along the Minnesota River was lost, and rights to the quarry at Pipestone, Minnesota, were also taken from the Dakota. This was a major blow to the standing of Little Crow in the Dakota community.

The land was divided into townships and plots for settlement. Logging and agriculture on these plots eliminated surrounding forests and prairies, which interrupted the Dakota's annual cycle of farming, hunting, fishing and gathering wild rice. Hunting by settlers dramatically reduced wild game, such as bison, elk, whitetail deer and bear. Not only did this decrease the meat available for the Dakota in southern and western Minnesota, but it directly reduced their ability to sell furs to traders for additional supplies.

Although payments were guaranteed, the US government was often behind or failed to pay because of Federal preoccupation with the American Civil War.[6] Most land in the river valley was not arable, and hunting could no longer support the Dakota community. The Dakota became increasingly discontented over their losses: land, non-payment of annuities, past broken treaties, plus food shortages and famine following crop failure. Tensions increased through the summer of 1862.

Negotiations

On August 4, 1862, representatives of the northern Sissetowan and Wahpeton Dakota bands met at the Upper Sioux Agency in the northwestern part of the reservation and successfully negotiated to obtain food. When two other bands of the Dakota, the southern Mdewakanton and the Wahpekute, turned to the Lower Sioux Agency for supplies on August 15, 1862, they were rejected. Indian Agent (and Minnesota State Senator) Thomas Galbraith managed the area and would not distribute food to these bands without payment.

At a meeting of the Dakota, the U.S. government and local traders, the Dakota representatives asked the representative of the government traders, Andrew Jackson Myrick, to sell them food on credit. His response was said to be, "So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung."[7] But the context of Myrick's comment at the time, early August 1862, is historically unclear.[8] Another version is that Myrick was referring to the Indian women who were already combing the floor of the fort's stables for any unprocessed oats to then feed to their starving children along with a little grass.[9]

The effect of Myrick's statement on Little Crow and his band was clear however. In a letter to General Sibley, Little Crow said it was a major reason for commencing war: "Dear Sir – For what reason we have commenced this war I will tell you. it is on account of Maj. Galbrait [sic] we made a treaty with the Government a big for what little we do get and then cant get it till our children was dieing with hunger – it is with the traders that commence Mr A[ndrew] J Myrick told the Indians that they would eat grass or their own dung."[10]

War

Early fighting

On August 16, 1862, the treaty payments to the Dakota arrived in St. Paul, Minnesota, and were brought to Fort Ridgely the next day. They arrived too late to prevent violence. On August 17, 1862, four young Dakota men were on a hunting trip in Acton Township, Minnesota, during which one stole eggs and then killed five white settlers.[11] Soon after, a Dakota war council was convened, their leader, Little Crow, agreed to continue attacks on the American settlements to try to drive out the whites. Many of the Dakota people, in particular Sisseton Wahpeton tribes, wanted no part in the attacks. Little Crow himself had been initially against an uprising and agreed to lead it only after an angry young brave called him a coward.[12][13][14] As a result of a majority of the 4,000 members of the Northern tribes being opposed to the war, their bands played no role in the early killings.[15] Historian Mary Wingerd has stated that it is "a complete myth that all the Dakota people went to war against the United States" and that it was rather "a faction that went on the offensive".[14]

On August 18, 1862, Little Crow led a group that attacked the Lower Sioux (or Redwood) Agency. Andrew Myrick was among the first who were killed. He was discovered trying to escape through a second-floor window of a building at the agency. Myrick's body later was found with grass stuffed into his mouth. The warriors burned the buildings at the Lower Sioux Agency, giving enough time for settlers to escape across the river at Redwood Ferry. Minnesota militia forces and B Company of the 5th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment, sent to quell the uprising, were defeated at the Battle of Redwood Ferry. Twenty-four soldiers, including the party's commander (Captain John Marsh), were killed in the battle.[16] Throughout the day, Dakota war parties swept the Minnesota River Valley and near vicinity, killing many settlers. Numerous settlements including the townships of Milford, Leavenworth and Sacred Heart, were surrounded and burned and their populations nearly exterminated.

Early Dakota offensives

Confident with their initial success, the Dakota continued their offensive and attacked the settlement of New Ulm, Minnesota, on August 19, 1862, and again on August 23, 1862. Dakota warriors had initially decided not to attack the heavily defended Fort Ridgely along the river, and turned toward the town, killing settlers along the way. By the time New Ulm was attacked, residents had organized defenses in the town center and were able to keep the Dakota at bay during the brief siege. Dakota warriors penetrated parts of the defenses and burned much of the town.[17] By that evening, a thunderstorm dampened the warfare, preventing further Dakota attacks.

Regular soldiers and militia from nearby towns (including two companies of the 5th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry. then stationed at Fort Ridgely) reinforced New Ulm. Residents continued to build barricades around the town.

The Dakota attacked Fort Ridgely on August 20 and 22, 1862.[18][19] Although the Dakota were not able to take the fort, they ambushed a relief party from the fort to New Ulm on August 21. The defense at the Battle of Fort Ridgely further limited the ability of the American forces to aid outlying settlements. The Dakota raided farms and small settlements throughout south central Minnesota and what was then eastern Dakota Territory.

Minnesota militia counterattacks resulted in a major defeat of American forces at the Battle of Birch Coulee on September 2, 1862. The battle began when the Dakota attacked a detachment of 150 American soldiers at Birch Coulee, 16 miles (26 km) from Fort Ridgely. The detachment had been sent out to find survivors, bury American dead and report on the location of Dakota fighters. A three-hour firefight began with an early morning assault. Thirteen soldiers were killed and 47 were wounded, while only two Dakota were killed. A column of 240 soldiers from Fort Ridgely relieved the detachment at Birch Coulee the same afternoon.

Attacks in northern Minnesota

Farther north, the Dakota attacked several unfortified stagecoach stops and river crossings along the Red River Trails, a settled trade route between Fort Garry (now Winnipeg, Manitoba) and Saint Paul, Minnesota, in the Red River Valley in northwestern Minnesota and eastern Dakota Territory. Many settlers and employees of the Hudson's Bay Company and other local enterprises in this sparsely populated country took refuge in Fort Abercrombie, located in a bend of the Red River of the North about 25 miles (40 km) south of present-day Fargo, North Dakota. Between late August and late September, the Dakota launched several attacks on Fort Abercrombie; all were repelled by its defenders.

In the meantime, steamboat and flatboat trade on the Red River came to a halt. Mail carriers, stage drivers and military couriers were killed while attempting to reach settlements such as Pembina, North Dakota, Fort Garry, St. Cloud, Minnesota, and Fort Snelling. Eventually, the garrison at Fort Abercrombie was relieved by a U.S. Army company from Fort Snelling, and the civilian refugees were removed to St. Cloud.

Army reinforcements

Due to the demands of the American Civil War, the region's representatives had to repeatedly appeal for aid before President Abraham Lincoln formed the Department of the Northwest on September 6, 1862, and appointed General John Pope to command it with orders to quell the violence. He led troops from the 3rd Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment and 4th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment. The 9th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment and 10th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment, which were still being constituted, had troops dispatched to the front as soon as companies were formed.[20][21] Minnesota Governor Alexander Ramsey also enlisted the help of Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley (the previous governor) to aid in the effort.

After the arrival of a larger army force, the final large-scale fighting took place at the Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, 1862. According to the official report of Lieutenant Colonel William R. Marshall of the 7th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment, elements of the 7th Minnesota and the 6th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment (and a six-pounder cannon) were deployed equally in dugouts and in a skirmish line. After brief fighting, the forces in the skirmish line charged against the Dakota (then in a ravine) and defeated them overwhelmingly.

Among the Citizen Soldier units in Sibley's expedition:

- Captain Joseph F. Bean's Company "The Eureka Squad"

- Captain David D. Lloyd's Company

- Captain Calvin Potter's Company of Mounted Men

- Captain Mark Hendrick's Battery of Light Artillery

- 1st Lieutenant Christopher Hansen's Company "Cedar Valley Rangers" of the 5th Iowa State Militia, Mitchell County, Iowa

- elements of the 5th & 6th Iowa State Militia

Iowa Northern Border Brigade

In Iowa, alarm over the Dakota attacks led to the construction of a line of forts from Sioux City to Iowa Lake. The region had already been militarized because of the Spirit Lake Massacre in 1857. After the 1862 conflict began, the Iowa Legislature authorized "... not less than 500 mounted men from the frontier counties at the earliest possible moment, and to be stationed where most needed," though this number was soon reduced. Although no fighting took place in Iowa, the Dakota uprising led to the rapid expulsion of the few remaining unassimilated Indians.[22][23]

Surrender of the Dakota

Most Dakota fighters surrendered shortly after the Battle of Wood Lake at Camp Release on September 26, 1862. The place was so named because it was the site where the Dakota released 269 American captives to the troops commanded by Colonel Sibley. The captives included 162 "mixed-bloods" (mixed-race, some likely descendants of Dakota women who were mistakenly counted as captives) and 107 whites, mostly women and children. Most of the warriors were imprisoned before Sibley arrived at Camp Release.[24]:249 The surrendered Dakota warriors were held until military trials took place in November 1862. Of the 498 trials, 300 were sentenced to death, though the president commuted all but 38.[25]

Little Crow was forced to retreat sometime in September 1862. He stayed briefly in Canada but soon returned to the Minnesota area. He was killed on July 3, 1863, near Hutchinson, Minnesota, while gathering raspberries with his teenage son. The pair had wandered onto the land of white settler Nathan Lamson, who shot at them to collect bounties. Once it was discovered that the body was of Little Crow, his skull and scalp were put on display in St. Paul, Minnesota. The city held the trophies until 1971, when it returned the remains to Little Crow's grandson. For killing Little Crow, the state granted Lamson an additional $500 bounty. For his part in the warfare, Little Crow's son was sentenced to death by a military tribunal, a sentence commuted to a prison term.

Trials

The trials of the Dakota prisoners were deficient in many ways, even by military standards; and the officers who oversaw them did not conduct them according to military law. The hundreds of trials commenced on 28 September 1862 and were completed on 3 November; some lasted less than 5 minutes. No one explained the proceedings to the defendants, nor were the Sioux represented by defense attorneys. "The Dakota were tried, not in a state or federal criminal court, but before a military commission. They were convicted, not for the crime of murder, but for killings committed in warfare. The official review was conducted, not by an appellate court, but by the President of the United States. Many wars took place between Americans and members of the Indian nations, but in no others did the United States apply criminal sanctions to punish those defeated in war."[26] The trials were also conducted in an atmosphere of extreme racist hostility towards the defendants expressed by the citizenry, the elected officials of the state of Minnesota and by the men conducting the trials themselves. "By November 3, the last day of the trials, the Commission had tried 392 Dakota, with as many as 42 tried in a single day."[ibid.] Not surprisingly, given the socially explosive conditions under which the trials took place, by the 10th of November the verdicts were in, and it was announced to the nation and the world that 303 Sioux prisoners had been convicted of murder and rape by the military commission and sentenced to death.

President Lincoln was informed by Maj. Gen. John Pope (military officer) of the sentences on 10 November 1862 in a telegraphic dispatch from Minnesota. His response to Pope was: "Please forward, as soon as possible, the full and complete record of these convictions. And if the record does not indicate the more guilty and influential, of the culprits, please have a careful statement made on these points and forwarded to me. Please send all by mail."[27]

When the death sentences were made public, Henry Whipple, the Episcopal bishop of Minnesota and a reformer of U.S. Indian policy, responded by publishing an open letter. He also went to Washington DC in the fall of 1862 to urge Lincoln to proceed with leniency.[28] On the other hand, General Pope and Minnesota Senator Morton S. Wilkinson warned Lincoln that the white population opposed leniency. Governor Ramsey warned Lincoln that, unless all 303 Sioux were executed, "[P]rivate revenge would on all this border take the place of official judgment on these Indians."[29]

Lincoln somehow - despite his many other pressing responsibilities in running the country and conducting the War - completed his review of the transcripts of the 303 trials in under a month; and on 11 December 1862, he addressed the Senate regarding his final decision (as he had been requested to do by a resolution passed by that body on 5 December 1862): "Anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on the one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other, I caused a careful examination of the records of trials to be made, in view of first ordering the execution of such as had been proved guilty of violating females. Contrary to my expectations, only two of this class were found. I then directed a further examination, and a classification of all who were proven to have participated in massacres, as distinguished from participation in battles. This class numbered forty, and included the two convicted of female violation. One of the number is strongly recommended by the commission which tried them for commutation to ten years' imprisonment. I have ordered the other thirty-nine to be executed on Friday, the 19th instant."[30]

In the end, Lincoln commuted the death sentences of 264 prisoners, but he allowed the execution of 39 men. However, "[on] December 23, [Lincoln] suspended the execution of one of the condemned men [...] after [General] Sibley telegraphed that new information led him to doubt the prisoner's guilt."[26] Thus, the number of condemned men was reduced to the final thirty-eight.

Even partial clemency resulted in protests from Minnesota, which persisted until the Secretary of the Interior offered white Minnesotans "reasonable compensation for the depredations committed." Republicans did not fare as well in Minnesota in the 1864 election as they had before. Ramsey (by then a senator) informed Lincoln that more hangings would have resulted in a larger electoral majority. The President reportedly replied, "I could not afford to hang men for votes."[31]

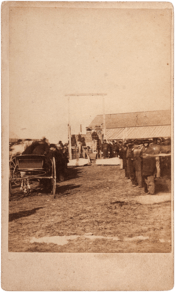

Execution

The Army executed the 38 remaining prisoners by hanging on December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota. It remains the largest mass execution in American history.

%2C_executed_at_Fort_Snelling%2C_November_11%2C_1865%2C_for_participating_in_the_massacre_of_1862%2C_by_Zimmerman%2C_Charles_A.%2C_1844-1909.jpg)

The mass execution was performed publicly on a single scaffold platform. After regimental surgeons pronounced the prisoners dead, they were buried en masse in a trench in the sand of the riverbank. Before they were buried, an unknown person nicknamed "Dr. Sheardown" possibly removed some of the prisoners' skin.[32] Small boxes purportedly containing the skin later were sold in Mankato.

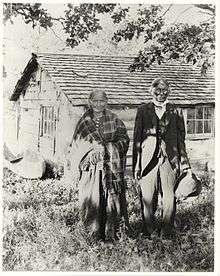

At least two Sioux leaders, Little Six and Medicine Bottle, escaped to Canada. They were captured, drugged, and returned to the United States. They were hanged at Fort Snelling in 1865.[33]

Medical aftermath

Because of the high demand for cadavers for anatomical study, several doctors wanted to obtain the bodies after the execution. The grave was reopened in the night and the bodies were distributed among the doctors, a practice common in the era. William Worrall Mayo received the body of Maȟpiya Akan Nažiŋ (Stands on Clouds), also known as "Cut Nose".

Mayo brought the body of Maȟpiya Akan Nažiŋ to Le Sueur, Minnesota, where he dissected it in the presence of medical colleagues.[34]:77–78 Afterward, he had the skeleton cleaned, dried and varnished. Mayo kept it in an iron kettle in his home office. His sons received their first lessons in osteology based on this skeleton.[34]:167 In the late 20th century, the identifiable remains of Maȟpiya Akan Nažiŋ and other Indians were returned by the Mayo Clinic to a Dakota tribe for reburial per the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.[35]

Internment

The remaining convicted Dakota were held in prison that winter. The following spring they were transferred to Camp McClellan in Davenport, Iowa, where they were imprisoned for almost four years.[36] By the time of their release, one-third of the prisoners had died of disease. The survivors were sent with their families to Nebraska. Their families had already been expelled from Minnesota.

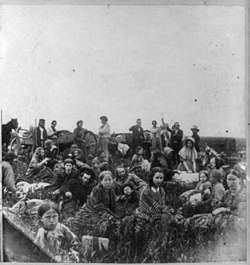

Pike Island internment

During this time, more than 1600 Dakota women, children and old men were held in an internment camp on Pike Island, near Fort Snelling, Minnesota. Living conditions and sanitation were poor, and infectious disease struck the camp, killing more than three hundred.[37] In April 1863, the U.S. Congress abolished the reservation, declared all previous treaties with the Dakota null and void, and undertook proceedings to expel the Dakota people entirely from Minnesota. To this end, a bounty of $25 per scalp was placed on any Dakota found free within the boundaries of the state.[38] The only exception to this legislation applied to 208 Mdewakanton, who had remained neutral or assisted white settlers in the conflict.

In May 1863, Dakota survivors were forced aboard steamboats and relocated to the Crow Creek Reservation, in the southeastern Dakota Territory, a place stricken by drought at the time. Many of the survivors of Crow Creek moved three years later to the Niobrara Reservation in Nebraska.[39][40]

Firsthand accounts

There are numerous firsthand accounts by European Americans of the wars and raids. For example, the compilation by Charles Bryant, titled Indian Massacre in Minnesota, included these graphic descriptions of events, taken from an interview with Justina Krieger:

Mr. Massipost had two daughters, young ladies, intelligent and accomplished. These the savages murdered most brutally. The head of one of them was afterward found, severed from the body, attached to a fish-hook, and hung upon a nail. His son, a young man of twenty-four years, was also killed. Mr. Massipost and a son of eight years escaped to New Ulm.[41]:141

The daughter of Mr. Schwandt, enceinte [pregnant], was cut open, as was learned afterward, the child taken alive from the mother, and nailed to a tree. The son of Mr. Schwandt, aged thirteen years, who had been beaten by the Indians, until dead, as was supposed, was present, and saw the entire tragedy. He saw the child taken alive from the body of his sister, Mrs. Waltz, and nailed to a tree in the yard. It struggled some time after the nails were driven through it! This occurred in the forenoon of Monday, 18th of August, 1862.[41]:300–301

S.P. Yeomans, editor of the Sioux City Register, circa May 30, 1863, wrote of the aftermath when the defeated Dakota were shipped to their new homes.[42]

The formerly favorite steamer, Florence," he wrote, "arrived at our levee on Tuesday; but instead of the cheerful faces of Capt. Throckmorten and Clerk Gorman we saw those of strangers; and instead of her usual lading of merchandise for our merchants, she was crowded from stem to stern, and from hold to hurricane deck with old squaws and papooses — about 1,400 in all — the non combative remnants of the Santee Sioux of Minnesota, en route to their new home….[43]

The Dakota have kept alive their own accounts of events suffered by their people.[44][45]

Continued conflict

After the expulsion of the Dakota, some refugees and warriors made their way to Lakota lands. Battles between the forces of the Department of the Northwest and combined Lakota and Dakota forces continued through 1864. In the 1863 operations against the Sioux in North Dakota, Colonel Sibley, with 2,000 men, pursued the Sioux into Dakota Territory. Sibley's army defeated the Lakota and Dakota in four major battles: the Battle of Big Mound on July 24, 1863; the Battle of Dead Buffalo Lake on July 26, 1863; the Battle of Stony Lake on July 28, 1863; and the Battle of Whitestone Hill on September 3, 1863. The Sioux retreated further, but faced Sully's Northwest Indian Expedition in 1864. General Alfred Sully led a force from near Fort Pierre, South Dakota, and decisively defeated the Sioux at the Battle of Killdeer Mountain on July 28, 1864 and at the Battle of the Badlands on August 9, 1864. The following year Sully's Northwest Indian Expedition of 1865 operated against the Sioux in Dakota Territory.

Conflicts continued. Within two years, settlers' encroachment on Lakota land sparked Red Cloud's War; the US desire for control of the Black Hills in South Dakota prompted the government to authorize an offensive in 1876 in what would be called the Black Hills War. By 1881, the majority of the Sioux had surrendered to American military forces. In 1890, the Wounded Knee Massacre ended all effective Sioux resistance.

Minnesota after the war

The Minnesota River valley and surrounding upland prairie areas were abandoned by most settlers during the war. Many of the families who fled their farms and homes as refugees never returned. Following the American Civil War, however, the area was resettled. By the mid-1870s, it was again being used and developed by European Americans for agriculture.

The federal government re-established the Lower Sioux Indian Reservation at the site of the Lower Sioux Agency near Morton. It was not until the 1930s that the US created the smaller Upper Sioux Indian Reservation near Granite Falls.

Although some Dakota had opposed the war, most were expelled from Minnesota, including those who attempted to assist settlers. The Yankton Sioux Chief Struck by the Ree deployed some of his warriors to aid settlers, but he was not judged friendly enough to be allowed to remain in the state immediately after the war. By the 1880s, a number of Dakota had moved back to the Minnesota River valley, notably the Good Thunder, Wabasha, Bluestone and Lawrence families. They were joined by Dakota families who had been living under the protection of Bishop Henry Benjamin Whipple and the trader Alexander Faribault.

By the late 1920s, the conflict began to pass into the realm of oral tradition in Minnesota. Eyewitness accounts were communicated first-hand to individuals who survived into the 1970s and early 1980s. The stories of innocent individuals and families of struggling pioneer farmers being killed by Dakota have remained in the consciousness of the prairie communities of south central Minnesota.[46] Descendants of the 38 Dakota killed, and their people, also remember the warfare and their people being dispossessed of their land and sent into exile in the west.

Monuments and memorials

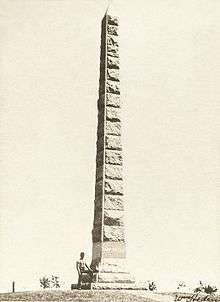

- The Camp Release State Monument commemorates the release of 269 European-American captives at the end of the conflict. The four faces of the 51-foot granite monument are inscribed with information about the battles that took place along the Minnesota River during the conflict, the surrender of the Dakota, and the creation of the monument.

- Large stone monuments at the Wood Lake Battlefield and in the parade ground of Fort Ridgely commemorate the battles and members of the military killed in action.

- The Morton Pioneer Monuments Roadside Park, four miles north of Morton, Minnesota along US highway 71, has two monuments honoring those who died during the Sioux War:

The Henderson Monument was erected in 1907 in memory of five members of the Henderson. It was originally located 1.5 miles southwest but was moved to its current location in 1981.

Randor Erle Monument, erected in 1907. Erle was killed on August 18, protecting his father.

- The Schwandt State Monument was erected in 1915 to memorialize the six members of the Schwandt family and one family friend. It is located sixteen miles south of Renville, Minnesota along Renville County Road 15.

- Redwood Ferry Monuments, honoring those who died at the Ambush on August 18. The monuments are on the north side of the Minnesota River near Morton and are inaccessible to the public. There is a roadside marker located on a bluff above the site along state highway 19 between Morton, Minnesota and Franklin, Minnesota

- The Defenders' State Monument, located at Center and State streets in New Ulm, was erected in 1891 by the State of Minnesota to honor the memory of the defenders who aided New Ulm during the Dakota War of 1862. The artwork at the base was created by New Ulm artist Anton Gag. Except for being moved to the middle of the block, the monument has not been changed since its completion.[47]

- In 1912, a four-ton monument was erected at the site in Mankato where the mass execution of the thirty-eight Dakota took place in 1862. In 1971, the City of Mankato, Minnesota removed the monument and placed it in the city storage. In the mid-1990s, it was discovered to be missing. It was possibly transferred to individuals within the Dakota Tribal Government.[48] In 1992, the City of Mankato purchased the site and created Reconciliation Park.[49] The mass execution is not referred to, but several stone statues in and around the park serve as a memorial. The annual Mankato Pow-wow, held in September, commemorates the lives of the executed men. Through this observance, the Dakota also seek to reconcile the European-American and Dakota communities. The Birch Coulee Pow-wow, held on Labor Day weekend, honors the lives of those who were hanged.

- The Acton, Minnesota State Monument to the first five casualties of the war who were killed in the attack on the Howard Baker farm. There is a roadside marker there as well.

- The Guri Endreson-Rosseland State Monument in the Vikor Lutheran Cemetery near Willmar, Minnesota. Dedicated to Mrs. Guri Enderson-Rosseland, who survived an attack at her home, and, in the following days, traveled the countryside assisting wounded settlers.

- The White Family Monument, located near Brownton, Minnesota. All four members of the White family were killed on September 22 at their home on Lake Addie. The monument stands near the site of their home.

- the Lake Shetek State Park monument to 15 white settlers killed there and at nearby Slaughter Slough on August 20, 1862.

- In 2012, for the 150th anniversary of the executions, different types of commemoration were conducted, including an episode of This American Life, and the release of films and documentaries. A group of Dakota rode on horseback from Brule, South Dakota, reaching Mankato on the day of the anniversary.[14] Their journey was filmed as the documentary Dakota 38. The memorial ride has continued uninterrupted since Dakota Elder Jim Miller shared his vision for the ride.[50]

In popular media

- In the Laura Ingalls Wilder novel, Little House on the Prairie (1935), Laura asks her parents about the Minnesota massacre, but they refuse to tell her any details.

- The uprising plays an important role in the historical novel The Last Letter Home (1959) by the Swedish author Vilhelm Moberg. It was the fourth novel of Moberg’s four-volume The Emigrants epic. These were based on the Swedish emigration to American and the author’s extensive research in the papers of Swedish emigrants in archival collections, including the Minnesota Historical Society.

- These novels were adapted as the Swedish films The Emigrants (1971) and The New Land (1972), both directed by Jan Troell. The latter film particularly portrays the period of the Dakota Wars and the historical mass execution. Stephen Farber of The New York Times said "its portrait of the Indians is one of the most interesting ever caught on film" and this is "an authentic American tragedy."[51]

- Poet Layli Long Soldier's poem "38" is about the massacre and was first published in Mud City Journal and later collected in her 2017 book Whereas.[52][53]

- In 2007, Minnesota House of Representatives member Dean Urdahl published his book "Uprising" about the events of 1862. In 2009, he published "Retribution", a sequel.

Several works were completed that marked the 150th anniversary of the mass execution:

- The This American Life episode "Little War on the Prairie" (aired November 23, 2012) discusses the continuing legacy of the conflict and mass executions in Mankato, Minnesota, marking the 150th anniversary of the events.[14]

- The Past Is Alive Within Us: The U.S.- Dakota Conflict (2013) is a video documentary examining Minnesota's involvement in the Dakota War during the Civil War, which had its major battlefields in the East. It provides both historical information and contemporary stories.

- Dakota 38 (2012) is an independent film filmed and directed by Silas Hagerty, which documents a long-distance ride made on horseback in 2008 by a group of Dakota from across the country. They rode from Lower Brule, South Dakota, over 330 miles to reach Mankato, Minnesota on the anniversary of the mass execution there of 38 Dakota men. They made the ride and the film "to encourage healing and reconciliation."[54]

See also

- We-Chank-Wash-ta-don-pee

- Indian massacre

- Philander Prescott

- Fort Ridgely State Park

- Monson Lake State Park

- Old Crossing Treaty

- Upper Sioux Agency State Park

- American Indian Wars

- List of massacres

References

- Kenneth Carley. The Dakota War of 1862.

- Clodfelter, Micheal D. (2006). The Dakota War: The United States Army Versus the Sioux, 1862-1865. McFarland Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7864-2726-0.

- Dee Brown Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian American History of the American West, p. 40, Henry Holt, Owl Book edition (1991, copyright 1970), trade paperback, 488 pages, ISBN 0-8050-1730-5.

- Kunnen-Jones, Marianne (August 21, 2002). "Anniversary Volume Gives New Voice To Pioneer Accounts of Sioux Uprising". University of Cincinnati. Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- Carly, Kenneth (1976). The Sioux Uprising of 1862 (Second edition ed.). Minnesota Historical Society.

- Douglas S. Benson (1996). Presidents at War: A Survey of United States Warfare History in Presidential Sequence 1775-1980. p. 328.

- Dillon, Richard H. (1920). North American Indian Wars. City: Booksales. p. 126.

- Michno, Gregory (November 5, 2012). "10 Myths on the Dakota Uprising". (2012). True West Magazine. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013.

- Anderson, Gary. (1983) "Myrick's Insult: A fresh look at Myth and Reality", Minnesota History Quarterly 48(5):198-206.

- Letter from Little Crow to Col. Henry Sibley(September 7, 1862) AG Report, 35-36

- Furst, Jay (December 22, 2012). "Dakota War timeline". Rochester Post-Bulletin. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- "Taoqateduta Is Not a Coward" (PDF). Minnesota Historical Society. September 1962. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- 1948-, Wingerd, Mary Lethert (2010). North country : the making of Minnesota. Delegard, Kirsten. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816673353. OCLC 670429639.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "479: Little War on the Prairie". This American Life. April 15, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- Linder, Douglas. "The Dakota Conflict (Sioux Uprising) Trials of 1862". www.famous-trials.com. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- Anderson, Little Crow, 130-39; Schultz, Over the Earth I Come, 48-58; Heard, History of the Sioux War, 73; Board of Commissioners, Minnesota in the Civil War, 2:112-14, 166-81.

- Burnham, Frederick Russell (1926). Scouting on Two Continents. New York: Doubleday, Page and Co. p. 2 (autobiographical account). ASIN B000F1UKOA.

- Soldiers: 3 killed/13 wounded; Lakota: 2 known dead.

- "Ft. Rid". The Dakota Conflict of 1862: Battles. Mankato Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved April 6, 2007.

- Minn Board of Commissioners (October 2005). Andrews, C. C. (ed.). Minnesota in the Civil and Indian Wars, 1861-1865: Two Volume Set with Index. Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-87351-519-1. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- "History – Minnesota Infantry (Part 1)". Union Regimental Histories. The Civil War Archive. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- Rogers, Leah D. (2009). "Fort Madison, 1808-1813". In William E. Whittaker (ed.). Frontier Forts of Iowa: Indians, Traders, and Soldiers, 1682–1862. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. pp. 193–206. ISBN 978-1-58729-831-8.

- McKusick, Marshall B. (1975). The Iowa Northern Border Brigade. Iowa City, Iowa: Office of the State Archaeologist, The University of Iowa.

- Schultz, Duane (1992). Over the Earth I Come: The Great Sioux Uprising of 1862. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-07051-9.

- Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events of the year: 1862. New York: D. Appleton & Company. 1863. p. 588.

- Chomsky, Carol (1990). "The United States-Dakota War Trials: A Study in Military Injustice". University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository. University of Minnesota Law School. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

- Lincoln, Abraham (November 10, 1862). To John Pope. Wildside Press, LLC. p. 493. ISBN 978-1-4344-7707-1.

- "History Matters". Minnesota Historical Society. March–April 2008. p. 1.

- Abraham Lincoln (October 30, 2008). The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Wildside Press LLC. p. 493. ISBN 978-1-4344-7707-1.

- Lincoln, Abraham (December 11, 1862). "Message to the Senate Responding to the Resolution Regarding Indian Barbarities in the State of Minnesota". The American Presidency Project. University of California, Santa Barbara. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

- Donald, David Herbert (1995). Lincoln. New York, New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 394–95.

- "Human Remains from Mankato, MN in the Possession of the Public Museum of Grand Rapids, Grand Rapids, MI". National Park Service. April 8, 2000. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

- Winks, Robin W. (1960). The Civil War Years: Canada and the United States, Baltimore : Johns Hopkins Press, 1960, p. 174.

- Clapesattle, Helen (1969). The Doctors Mayo. Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic; 2nd edition. ISBN 978-5-555-50282-7.

- Records of the Mayo Clinic.

- "The Two Sides of Camp McClellan". Davenport Public Library. Archived from the original on April 30, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- Monjeau-Marz, Corinne L. (October 10, 2005). Dakota Indian Internment at Fort Snelling, 1862–1864. Prairie Smoke Press. ISBN 978-0-9772718-1-8.

- https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=none&httpsredir=1&article=1261&context=facsch

- "Where the Water Reflects the Past". The Saint Paul Foundation. October 31, 2005. Retrieved December 12, 2006.

- "family History". Census of Dakota Indians Interned at Fort Snelling After the Dakota War in 1862. Minnesota Historical Society. 2006. Archived from the original on February 20, 2007. Retrieved December 12, 2006.

- Bryant, Charles S.; Abel B. Murch (1864). A history of the great massacre by the Sioux Indians in Minnesota : including the personal narratives of many who escaped. Chicago: O.C. Gibbs. ISBN 978-1-147-00747-3.

- "Siouxland Observer: Exiled: The Northwest Tribes".

- "Riverfront Eyewitness". Google Docs.

- Mark Steil, "Exiled at Crow Creek", Minnesota Public Radio; Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- "Let Them Eat Grass".

- Mark Steil & Tim Post (September 26, 2002). Minnesota's Uncivil War (Minnesota Public Radio). Minneapolis-St. Paul: KNOW-FM. Remnants of war.

- "Defender's Monument" (PDF). Brown County Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 5, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- Dan Linehan, "Students search for missing monument as part of history class", The Free Press, Mankato, MN, 5/14/2006; Retrieved 1-17-2017.

- Barry, Paul. "Reconciliation – Healing and Remembering". Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

- Tim Krohn, "38 Dakota honored by riders, runners", The Free Press, Mankato, MN, 12/26/2018; Retrieved 5-7-2019.

- Farber, Stephen (November 18, 1973). "Movies". The New York Times. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- "One Poem By Layli Long Soldier". Mud City Journal. Archived from the original on August 8, 2018. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- Diaz, Natalie (August 4, 2017). "A Native American Poet Excavates the Language of Occupation". The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- Dakota 38, 2012, Smooth Feather Productions

Further reading

- Anderson, Gary and Alan Woolworth, editors. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. St Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988. ISBN 0-87351-216-2

- Beck, Paul N., Soldier Settler and Sioux: Fort Ridgely and the Minnesota River Valley 1853–1867. Sioux Falls, SD: Pine Hill Press, 2000.

- Beck, Paul N. Columns of Vengeance: Soldiers, Sioux, and the Punitive Expeditions, 1863-1864. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013.

- Berg, Scott W., 38 Nooses: Lincoln, Little Crow, and the Beginning of the Frontier's End. New York: Pantheon, 2012. ISBN 0-307377-24-5

- Chomsky, Carol. "The United States-Dakota War Trials: A Study in Military Injustice". 43 Stanford Law Review 13 (1990).

- Collins, Loren Warren. The Story of a Minnesotan, (private printing) (1912, 1913?). OCLC 7880929

- Cox, Hank. Lincoln And The Sioux Uprising of 1862, Cumberland House Publishing (2005). ISBN 1-58182-457-2

- Folwell, William W.; Fridley, Russell W. A History of Minnesota, Vol. 2, pp. 102–302, St Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1961. ISBN 978-0-87351-001-1

- Haymond, John A. The Infamous Dakota War Trials of 1862: Revenge, Military Law and the Judgment of History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2016. ISBN 1-476665-10-9

- Jackson, Helen Hunt. A Century of Dishonor: A Sketch of the United States Government's Dealings with some of the Indian Tribes (1887), Chapter V.: The Sioux, pp. 136–185.

- Johnson, Roy P. The Siege at Fort Abercrombie, State Historical Society of North Dakota (1957). OCLC 1971587

- Linder, Douglas The Dakota Conflict Trials of 1862 (1999).

- Nichols Roger L. Warrior Nations: The United States and Indian Peoples. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013.

- Nix, Jacob. The Sioux Uprising in Minnesota, 1862: Jacob Nix's Eyewitness History, Max Kade German-American Center (1994). ISBN 1-880788-02-0

- Schultz, Duane. Over The Earth I Come: The Great Sioux Uprising Of 1862. New York: St. Martin's Griffin (1993). ISBN 9780312093600

- Tolzmann, Don Heinrich, German Pioneer Accounts of the Great Sioux Uprising of 1862. Milford, OH: Little Miami Publishing, 2002. ISBN 978-0-9713657-6-6.

- Yenne, Bill. Indian Wars: The Campaign for the American West Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1-59416-016-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dakota War of 1862. |

- Dakota War of 1862 (Dakota Conflict) – Minnesota Historical Society bibliography

- Detailed history of trials, with documents

- Map of Indian battles and skirmishes AFTER the Dakota War. 1862-1872.

- Dakota Conflict – timeline and links to area museums

- The Dakota Conflict of 1862

- Minnesota Historical Society History Topics: Dakota War of 1862

- Wisconsin Historical Society Sioux Uprising of 1862

- "Wood Lake Battlefield Preservation Association"

- Dakota Conflict Documentary produced by Twin Cities Public Television (also here)

- Dakota Exile Documentary produced by Twin Cities Public Television (also here)