Little Crow

Little Crow V (Dakota: Thaóyate Dúta; ca. 1810 – July 3, 1863) was a chief of a band of the Mdewakanton Dakota people, who were based along the Minnesota River. His given name translates as "His Red Nation," (Thaóyate Dúta). He was known as Little Crow because of a mistranslation by Europeans of his grandfather's name, Čhetáŋ Wakhúwa Máni (literally, "Hawk that chases/hunts walking").

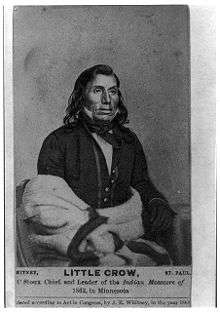

Little Crow | |

|---|---|

Taoyateduta, known as Little Crow | |

| Born | c. 1810 Kaposia (now in South St. Paul, Minnesota) |

| Died | July 3, 1863 Minnesota |

| Known for | Chief of the Mdewakanton Dakota people |

| Spouse(s) | ? |

| Children | Thomas Wakeman |

Little Crow is notable for his role in negotiating the treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota of 1851, in which he agreed to remove his band of Dakota to a reservation near the Minnesota River in exchange for annuity goods and payments. In the summer of 1862, the federal government failed to deliver annuities in a timely way, and there were rumors that the 'Great Council' Congress had expended all their gold fighting the great Civil War and could not send any money to the indians, which left the Dakota starving.[1] Little Crow supported the decision of a Dakota war council in August 1862 to try to drive the whites out of the region. Little Crow led warriors in the Dakota War of 1862, but retreated in September 1862 before the war's conclusion in December of that year.

Little Crow was shot and killed on July 3, 1863 by two white settlers, a man and his son. He was scalped and his body was taken to Hutchinson, Minnesota, where it was ritually humiliated and mutilated by white settlers. Some time later his remains were exhumed by Army troops, and eventually the Minnesota Historical Society held and displayed them publicly.[2] In 1971 the Society repatriated his remains, giving them to his grandson. He had Little Crow reinterred at the First Presbyterian Church and Cemetery in Flandreau, South Dakota. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2017.

Early life

Little Crow was born at the Dakota settlement of Kaposia just below present-day Indian Mounds Park.[3] His father died in 1846 after accidentally discharging a gun. Band leadership was disputed between Little Crow and his brother. They had an armed fight that resulted in Little Crow being wounded in both wrists. This left scars that he concealed with long sleeves for the rest of his life. He had a third physical oddity, a double row of teeth.[4] By 1849, Little Crow took control of his band.

In 1851, the United States negotiated the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux and the Treaty of Mendota with the Dakota people. Little Crow was present at Traverse des Sioux and signed the Mendota treaty,[5] by which the bands agreed to move to land set aside along the Minnesota River to the west of their traditional territory.[6] The treaty as ratified by the United States Senate removed Article 3 of the treaty, which had set aside this land.[6] The tribe was compelled to negotiate a new treaty, under threat of forcible removal to the Dakota Territory, and was granted land only on one side of the river.

Little Crow tried to adapt to customs of the United States.[7] He visited President James Buchanan in Washington, D.C., replaced his native clothing with trousers and jackets with brass buttons, joined the Episcopal Church, and took up farming. However, by 1862, his band was starving. Crops had failed on their small reservation, game was overhunted, and Congress failed to pay the annuities mandated by treaty. Payments were delayed because of the outbreak of the American Civil War. As the tribe grew hungry and as food languished in traders' warehouses at the Sioux agencies, Little Crow's ability to restrain his people deteriorated.

Dakota War of 1862

On August 4, 1862, about five hundred Dakota broke into food warehouses at the Lower Agency. The agent in charge, Thomas J. Galbraith, ordered defending troops not to shoot and called for a council. At the conference, Little Crow pointed out that the Dakota were owed the money to buy the food and warned that "When men are hungry, they help themselves." The representative of the traders, Andrew Myrick, replied, "So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry let them eat grass."

Within weeks, on August 17, 1862, a band of Dakota crossed paths with a group of white civilian settlers. The Dakota killed five of the settlers, mutilating their bodies in ritual fashion.

The band's need for food and failures by the federal government and trades resulted in the Dakota War of 1862. Little Crow agreed to lead the bands through the conflict, even though he knew the whites could ultimately send larger numbers of troops into the conflict than his people could counter. The Dakota first attacked the Lower Sioux agency; they scalped Myrick and stuffed his mouth with grass in a sense of revenge.

Under Taoyateduta's leadership, the Dakota had some success in the ambush of a small detachment of US troops under Captain Marsh at Redwood ferry, an attack on a burial party in the Battle of Birch Coulee, and killing many unprepared settlers. However, two Dakota attacks on Fort Ridgely were thwarted by soldiers and civilians who, although outnumbered, used the fort's cannon to drive off the attackers. Little Crow was wounded by cannon fire in the second attack on Fort Ridgely, and did not join the attack on New Ulm. The Dakota attacked New Ulm twice, and a collection of settlers and volunteers staved off the warriors although they were outnumbered. Attacks on Forest City, Hutchinson, and Fort Abercrombie were also repulsed. The Dakota attacked white civilians throughout the area.[8] In the end, Little Crow's forces suffered a rout at the Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, 1862, after which Little Crow and many of his warriors fled west, taking three white boys with them as captives. One of the boys, George Washington Ingalls[9] age 9 (cousin to author Laura Ingalls) had witnessed the killing and scalping of his father Jedidiah and the capture of his three sisters at the start of the conflict. By late spring 1863, Little Crow and his followers were camped near the Canada–US border. They ransomed the boys in early June 1863, in exchange for blankets and horses.[10]

Death

Deciding that the tribe must adopt a mobile existence, having been robbed of its territory, Little Crow led a raiding party to steal horses from his former land in Minnesota. His people did not want to do this. On the evening of July 3, 1863, while he and his son Wowinapa were picking raspberries,[11] they were spotted by Nathan Lamson and his son Chauncey. The four engaged in a brief firefight. Little Crow wounded the elder Lamson, but was mortally shot by both Lamson and his son. The chief told his own son to flee.[12]

The Lamsons separated, and each traveled the nearly 12 miles to Hutchinson, Minnesota to raise the alarm. The next day, a search party returned and found the body of an unidentified Dakota man. The body wore a coat they recognized as belonging to white settler James McGannon, who had been killed two days before.[13] They scalped the Dakota man, and later brought the body back to Hutchinson. They then dragged his body along the town's Main Street. Firecrackers were placed in his ears and nose and lit. The body was ultimately tossed into a pit at a slaughterhouse. It was later decapitated.[14]

On July 28, 1863, Wowinapa was captured by US Army troops in the vicinity of Devil's Lake, Dakota Territory. He told the troops of Little Crow's death. Officials tracked down and exhumed the chief's body on August 16. Little Crow's identity was verified by his scarred wrists. The next year, the Legislature awarded Nathan Lamson $500 for "rendering great service to the State".[15] His son Chauncey Lamson received a $75 bounty for the scalp, although he had taken it the same day that the Adjutant General's bounty on Dakota warriors was declared on July 4, 1863.[16]

The Minnesota Historical Society acquired Little Crow's scalp in 1868, and his skull in 1896. Other bones were collected at other times. These human trophies were displayed publicly for decades.[2] In 1971, the Society returned Little Crow's remains to his grandson Jesse Wakeman (son of Wowinapa) for burial.[14] A small stone memorial tablet was installed at the roadside of the field where Little Crow was killed.

Legacy

- In 1937, the city of Hutchinson erected a large bronze statue of Little Crow in a spot overlooking the Crow River near the Main Street bridge access to the downtown business district. It was created by local artist Les Kouba, who later became known for his wildlife art.[17]

- In 1971 Jesse Wakemen arranged to have the remains of his grandfather Little Crow reinterred at the First Presbyterian Church and Cemetery in Flandreau, South Dakota. The church and cemetery were listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 2017.[18]

- In 1982, sculptor Robert Johnson and Kouba created an updated statue of Little Crow for the city of Hutchinson, as the older one was weather beaten. It was removed in 2007 and held at the McLeod County Historical Society in order to allow construction of a new Main Street bridge across the river. Eheim Park was redesigned here, and the statue was planned to be reinstalled in a lower position in 2009, so that viewers could appreciate the symbols on the cape. The statue again overlooks the Crow River.[19]

- A mask commemorating Little Crow was installed near the waterfall in Minnehaha Park in Minneapolis,[20] however the foundry says there is no correlation between Little Crow and the site.[21]

Notes

- Brown, Dee (1970). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. United States of America: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. pp. 39–40. LCCN 70-121633.

- "Little War on the Prairie". This American Life. Season 2012. Episode 479. 2012-11-23. 48 minutes in.

Little Crow was shot six months after the hangings and his scalp, skull, and wristbones were displayed at the Minnesota Historical Society for decades.

- "Kaposia Indian Site". Mississippi National River and Recreation Area, Minnesota. National Park Service. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- Trenerry, Walter N. (Fall 1962). "The Shooting of Little Crow: Heroism or Murder?" (PDF). Minnesota History. Minnesota Historical Society. 38 (3): 151.

- Mayer (1986), pp. 149, 202, 242.

- "Treaty with the Sioux — Mdewakanton and Wahpakoota Bands, 1851". Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on 2007-07-11. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- Brown, Dee (1970) Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, ISBN 0-330-23219-3, chapter 2: "Little Crow's War"

- Burnham, Frederick Russell (1926). Scouting on Two Continents. New York: Doubleday, Page and Co. p. 2 (autobiographical account). ASIN B000F1UKOA.

- "George Washington Ingalls". Find A Grave. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- "Dakota War Hoop" pgs 308-9, "A History of the Great Massacre by the Sioux Indians in Minnesota" pg 131 Bryant & Murch, "South Dakota Historical Collections", Vol 5, pp. 304-5, footnote #65, by the South Dakota State Historical Society.

- Calloway, Colin G. (Colin Gordon), 1953- (2007-10-31). First peoples : a documentary survey of American Indian history (Third ed.). Boston. ISBN 9780312453732. OCLC 182574759.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- John Christgau (1 March 2012). Birch Coulie: The Epic Battle of the Dakota War. U of Nebraska Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8032-4015-5.

- Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society, Volume 15, pp. 367-370

- "Little Crow's legacy". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2018-02-17.

- Minnesota Special Laws 1864, Chapter 84

- , Minnesota History Magazine, pp. 150-153

- "Little Crow statue". McLeod County Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2007-12-18. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- "Six more state properties". South Dakota Historical Society. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- "Where's Little Crow?" Editorial in the Hutchinson Leader, 7 May 2009; Accessed 26 Oct. 2012

- "Minnehaha Park". Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board. Archived from the original on February 12, 2007. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- Per Note 58 on page 172, in Rachel McLean Sailor (2014). Meaningful Places: Landscape Photographers in the Nineteenth-Century American West. University of New Mexico Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0826354235 – via Google Books.

References

- Anderson, Gary Clayton. (1986) Little Crow, spokesman for the Sioux. Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press.[1] A reviewer in New Mexico Historical Review calls Anderson's book a "major contribution to our understanding of an Indian tribe that profoundly influenced the course of history in the upper Mississippi Valley, partly at least through the personal role played by its most famous leader."[2]

- Carley, Kenneth. (2001) The Dakota War of 1862. Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

- Clodfelter, Michael. (1998) The Dakota War: The United States Army Versus the Sioux, 1862-1865. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland.

- Mayer, Frank Blackwell. (1986) With Pen and Pencil on the Frontier in 1851. Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87351-195-6.

- Nix, Jacob. (1994) The Sioux Uprising in Minnesota, 1862: Jacob Nix's Eyewitness History. Gretchen Steinhauser, Don Heinrich Tolzmann & Eberhard Reichmann, trans. Don Heinrich Tolzmann, ed. Indianapolis: Max Kade German-American Center, Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis and Indiana German Heritage Society, Inc.

- Schultz, Duane. (1992) Over the Earth I Come: The Great Sioux Uprising of 1862. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Swain, Gwenyth. (2004) Little Crow: Leader of the Dakota. Saint Paul, MN, Borealis Books.

- Tolzmann, Don Heinrich, ed. (2002) German Pioneer Accounts of the Great Sioux Uprising of 1862. Milford, Ohio: Little Miami Publishing Co.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Little Crow. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Little Crow |

- Little Crow Trail

- Minnesota Historical Society History Topics: Dakota War of 1862

- Documentary on Little Crow, Google Video

- Dakota Blues - The history of The Great Sioux Nation

- Little Crow Monument by Les Kouba, Hutchinson

- Flickriver Photo Gallery

- Anderson, Gary Clayton (1986). Little Crow: Spokesman for the Sioux. St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 0873511964. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- "Review: Little Crow: Spokesman for the Sioux". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on November 11, 2010. Retrieved October 23, 2010.