Emancipation Memorial

The Emancipation Memorial, also known as the Freedman's Memorial or the Emancipation Group is a monument in Lincoln Park in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Washington, D.C. It was sometimes referred to as the "Lincoln Memorial" before the more prominent so-named memorial was dedicated in 1922.[3][4]

| Emancipation Memorial | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Thomas Ball |

| Year | 1876 |

| Type | Bronze |

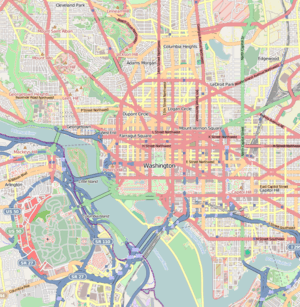

| Location | Lincoln Park (Washington D.C.), United States |

| Owner | National Park Service |

Emancipation Memorial | |

| |

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°53′23.3″N 76°59′24.9″W |

| Part of | Civil War Monuments in Washington, DC. |

| NRHP reference No. | 78000257[1] |

| Added to NRHP | September 20, 1978 [2] |

Designed and sculpted by Thomas Ball and erected in 1876, the monument depicts Abraham Lincoln holding a copy of his Emancipation Proclamation freeing a male African American slave modeled on Archer Alexander. The ex-slave is depicted on one knee, with one fist clenched, shirtless and broken shackles at the president's feet.[3]

The Emancipation Memorial statue was funded by the wages of freed slaves.

The statue originally faced west towards the U.S. Capitol until it was rotated east in 1974 in order to face the newly erected Mary McLeod Bethune Memorial.[5]

The statue is a contributing monument to the Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C., of the National Register of Historic Places.

Funding

The funding drive for the monument began, according to much-publicized newspaper accounts from the era, with $5 given by former slave Charlotte Scott of Virginia, then residing with the family of her former master in Marietta, Ohio, for the purpose of creating a memorial honoring Lincoln.[6][7] The Western Sanitary Commission, a St. Louis-based volunteer war-relief agency, joined the effort and raised some $20,000 before announcing a new $50,000 goal.[8]

According to the National Park Service, the monument was paid for solely by former slaves:

The campaign for the Freedmen's Memorial Monument to Abraham Lincoln, as it was to be known, was not the only effort of the time to build a monument to Lincoln; however, as the only one soliciting contributions exclusively from those who had most directly benefited from Lincoln's act of emancipation it had a special appeal ... The funds were collected solely from freed slaves (primarily from African American Union veterans) ...

The turbulent politics of the reconstruction era affected the fundraising campaign on many levels. The Colored People's Educational Monument Association headed by Henry Highland Garnet wanted the monument to serve a didactic purpose as a school where freedmen could elevate themselves through learning. Frederick Douglass disagreed and thought the goal of education was incommensurate with that of remembering Lincoln.[9]

Design and construction

Harriet Hosmer proposed a grander monument than that suggested by Thomas Ball. Her design, which was ultimately deemed too expensive, posed Lincoln atop a tall central pillar flanked by smaller pillars topped with black Civil War soldiers and other figures.[3]

When Ball's design was finally chosen, the commission insisted on certain changes. Instead of wearing a liberty cap, the slave in the revised monument is depicted bare-headed with tightly curled hair. The face was re-sculpted to look like Archer Alexander, an ex-slave whose life story was popularized by a biography written by William Greenleaf Eliot.

In the final design, as in Ball's original design, Lincoln holds a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation in his right hand. The document rests on a plinth bearing patriotic symbols including George Washington's profile, the fasces of the U.S. republic, and a shield emblazoned with the stars and stripes. The plinth replaces the pile of books in Ball's original design. Behind the two figures is a whipping post draped with cloth. A vine grows around the pillory and around the ring where the chain was secured.[10][11]

The monument was cast in Munich in 1875 and shipped to Washington the following year. Congress accepted the statue as a gift from the "colored citizens of the United States" and appropriated $3,000 for a pedestal upon which it would rest. The statue was erected in Lincoln Park, where it still stands.[4]

A plaque on the monument names it as "Freedom's Memorial in grateful memory of Abraham Lincoln" and reads:

This monument was erected by the Western Sanitary Commission of Saint Louis Mo: With funds contributed solely by emancipated citizens of the United States declared free by his proclamation January 1 A.D. 1863. The first contribution of five dollars was made by Charlotte Scott. A freedwoman of Virginia being her first earnings in freedom and consecrated by her suggestion and request on the day she heard of President Lincoln's death to build a monument to his memory[4]

Dedication

Frederick Douglass spoke as the keynote speaker at the dedication service on April 14, 1876, with President Ulysses S. Grant in attendance.[12][13]

Other versions

In 1879, Moses Kimball, for whom Ball had once worked at the Boston Museum, donated a copy of the statue to Boston. It is sited in Park Square.[14]

Architect Edward Francis Searles purchased an early small demonstration version from Ball and brought it to Methuen, Massachusetts, where it rests in the Town Hall atrium.

The Chazen Museum of Art, located on the campus of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was gifted a version of the statue in white marble by Dr. Warren E. Gilson in 1976.[15]

Criticism

The monument has been criticized for its paternalistic character and for not doing justice to the role that African Americans played in their own liberation. While the funds for the monument were raised from former slaves, an all-white committee oversaw the design. An alternative design depicting Lincoln with uniformed black Union soldiers was rejected as too expensive. According to historian Kirk Savage, a witness to the memorial's dedication recorded Frederick Douglass as saying that the statue "showed the Negro on his knees when a more manly attitude would have been indicative of freedom."[16] [17] According to information from American University:[3]

If there is one slavery monument whose origins are highly political, the Freedman's memorial is it. The development process for this memorial started immediately after Abraham Lincoln's assassination and ended, appropriately enough, near the end of Reconstruction in 1876. In many ways, it exemplified and reflected the hopes, dreams, striving, and ultimate failures of reconstruction.

On June 23, 2020, DC delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton announced plans to introduce legislation to remove the memorial.[18] That same day, protesters on site vowed to dismantle the statue on Thursday, June 25 at 7:00 p.m. local time.[19] Subsequently, a barrier fence was installed around the memorial to protect it from vandalism.[20]

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Civil War Monuments in Washington, DC". National Park Service. September 20, 1978. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- American University: Great Emancipator, Supplicant Slave: The Freedman's Memorial to Abraham Lincoln. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- National Park Service: Lincoln Park. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- "Lincoln Park – Capitol Hill Parks (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-12.

- Forman, J. G (1864), The Western Sanitary Commission: A Sketch, St. Louis: R. P. Studley & Co., pp. 131–138

- Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1997) pg. 90

- Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1997) pg. 92

- Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 93

- American University: Great Emancipator, Supplicant Slave: The Freedman's Memorial to Abraham Lincoln. In the description given here it says the slave's "arms are separated in an attempt to break his chains" when, in fact, the statue does not depict chains nor even a position suggesting physical exertion.

- Lincoln Park: Emancipation Memorial in Washington, DC by Thomas Ball

- O'Connor, Candace (April 9, 1989). "Close to Home: The Story Behind a Statue". The Washington Post. p. B8.

- Douglass, Frederick (1876). Oration by Frederick Douglass, Delivered on the Occasion of the Unveiling of the Freedmen's Monument in Memory of Abraham Lincoln, in Lincoln Park, Washington, D.C., April 14th, 1876. Gibson Brothers, Printers.

- Couper, Greta Elena. "Sculptor Thomas Ball". Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- Chazen Museum of Art. "Emancipation Group". Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- Heim, Joe (April 15, 2012). "On Emancipation Day in D.C., two memorials tell very different stories". The Washington Post.

- Murray, Freeman Henry Morris (1916). Emancipation and the freed in American sculpture ; a study in interpretation. Smithsonian Libraries. Washington, D.C., The author.

- "DC Congresswoman to introduce legislation to remove Emancipation Memorial from Lincoln Park". Fox 5. June 23, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- Boykin, Nick (June 23, 2020). "Protesters vow to tear down Emancipation Statue in Lincoln Park". WUSA9. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- O'Neill, Natalie (June 26, 2020). "Barrier installed to protect DC Emancipation Memorial from protesters". New York Post. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

Further reading

- Douglass, Frederick, "Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln, delivered at the unveiling of the Freedmen's Monument in Memory of Abraham Lincoln," April 14, 1876

- Helm, Joe, "On Emancipation Day in D.C., Two Memorials Tell Very Different Stories", The Washington Post, April 15, 2012

- Schaub, Diana, "Monumental Battles: Why we build memorials," The Weekly Standard, May 28, 2012: http://www.weeklystandard.com/article/monumental-battles/645177?page=1