Cradle of civilization

A cradle of civilization is a location where civilization is understood to have emerged. Current thinking is that there was no single "cradle", but several civilizations that developed independently, with the Fertile Crescent (Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia), Ancient India, and Ancient China understood to be the earliest.[1][2][3] The extent to which there was significant influence between the early civilizations of the Near East and those of East Asia (Far East) is disputed. Scholars accept that the civilizations of Mesoamerica, mainly in modern Mexico, and from Pacific Ocean coast in South America, emerged independently from those in Eurasia.[4]

| Part of a series on |

| Human history and prehistory |

|---|

| ↑ before Homo (Pliocene epoch) |

|

Prehistory (three-age system) |

| Recorded history |

|

| ↓ Future (Holocene epoch) |

Scholars have defined civilization using various criteria such as the use of writing, cities, a class-based society, agriculture, animal husbandry, public buildings, metallurgy, and monumental architecture.[5][6] The term cradle of civilization has frequently been applied to a variety of cultures and areas, in particular the Ancient Near Eastern Chalcolithic (Ubaid period) and Fertile Crescent, Ancient India and Ancient China. It has also been applied to ancient Anatolia, the Levant and Iranian plateau, and used to refer to culture predecessors—such as Ancient Greece as the predecessor of Western civilization[7]—even when such sites are not understood as an independent development of civilization, as well as within national rhetoric.[8]

History of the idea

The concept "cradle of civilization" is the subject of much debate. The figurative use of cradle to mean "the place or region in which anything is nurtured or sheltered in its earlier stage" is traced by the Oxford English Dictionary to Spenser (1590). Charles Rollin's Ancient History (1734) has "Egypt that served at first as the cradle of the holy nation".

The phrase "cradle of civilization" plays a certain role in national mysticism. It has been used in Eastern as well as Western cultures, for instance, in Indian nationalism (In Search of the Cradle of Civilization 1995) and Chinese nationalism (Chinese;— The Cradle of Civilization[8] 2002). The terms also appear in esoteric pseudohistory, such as the Urantia Book, claiming the title for "the second Eden", or the pseudoarchaeology related to Megalithic Britain (Civilization One 2004, Ancient Britain: The Cradle of Civilization 1921).

Rise of civilization

The earliest signs of a process leading to sedentary culture can be seen in the Levant to as early as 12,000 BC, when the Natufian culture became sedentary; it evolved into an agricultural society by 10,000 BC.[9] The importance of water to safeguard an abundant and stable food supply, due to favourable conditions for hunting, fishing and gathering resources including cereals, provided an initial wide spectrum economy that triggered the creation of permanent villages.[10]

The earliest proto-urban settlements with several thousand inhabitants emerged in the Neolithic. The first cities to house several tens of thousands were Memphis and Uruk, by the 31st century BC (see Historical urban community sizes).

Historic times are marked apart from prehistoric times when "records of the past begin to be kept for the benefit of future generations";[11] which may be in written or oral form. If the rise of civilization is taken to coincide with the development of writing out of proto-writing, the Near Eastern Chalcolithic, the transitional period between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age during the 4th millennium BC, and the development of proto-writing in Harappa in the Indus Valley of South Asia around 3300 BC are the earliest incidences, followed by Chinese proto-writing evolving into the oracle bone script, and again by the emergence of Mesoamerican writing systems from about 900 BC.

In the absence of written documents, most aspects of the rise of early civilizations are contained in archaeological assessments that document the development of formal institutions and the material culture. A "civilized" way of life is ultimately linked to conditions coming almost exclusively from intensive agriculture. Gordon Childe defined the development of civilization as the result of two successive revolutions: the Neolithic Revolution, triggering the development of settled communities, and the Urban Revolution, which enhanced tendencies towards dense settlements, specialized occupational groups, social classes, exploitation of surpluses, monumental public buildings and writing. Few of those conditions, however, are unchallenged by the records: dense settlements were not attested in Egypt's Old Kingdom and were absent in the Maya area; the Incas lacked writing altogether (although they could keep records with Quipus); and often monumental architecture preceded any indication of village settlement. For instance, in present-day Louisiana, researchers have determined that cultures that were primarily nomadic organized over generations to build earthwork mounds at seasonal settlements as early as 3400 BC. Rather than a succession of events and preconditions, the rise of civilization could equally be hypothesized as an accelerated process that started with incipient agriculture and culminated in the Oriental Bronze Age.[12]

Single or multiple cradles

A traditional theory of the spread of civilization is that it began in the Fertile Crescent and spread out from there by influence.[13] Scholars more generally now believe that civilizations arose independently at several locations in both hemispheres. They have observed that sociocultural developments occurred along different timeframes. "Sedentary" and "nomadic" communities continued to interact considerably; they were not strictly divided among widely different cultural groups. The concept of a cradle of civilization has a focus where the inhabitants came to build cities, to create writing systems, to experiment in techniques for making pottery and using metals, to domesticate animals, and to develop complex social structures involving class systems.[4]

Current scholarship generally identifies six sites where civilization emerged independently:[6][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21]

- Fertile Crescent

- Tigris–Euphrates Valley

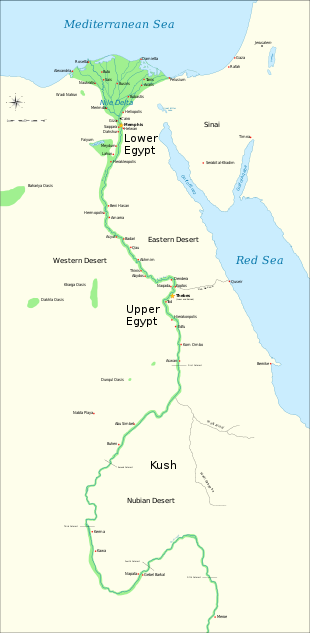

- Nile Valley

- Indo-Gangetic Plain

- North China Plain

- Andean Coast

- Mesoamerican Gulf Coast

Cradles of civilization

Fertile Crescent

Mesopotamia

Around 10,200 BC the first fully developed Neolithic cultures belonging to the phases Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) and Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (7600 to 6000 BC) appeared in the Fertile Crescent and from there spread eastwards and westwards.[22] One of the most notable PPNA settlements is Jericho in the Levant region, thought to be the world's first town (settled around 9600 BC and fortified around 6800 BC).[23][24] In Mesopotamia, the convergence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers produced rich fertile soil and a supply of water for irrigation. The civilizations that emerged around these rivers are among the earliest known non-nomadic agrarian societies. It is because of this that the Fertile Crescent region, and Mesopotamia in particular, are often referred to as the cradle of civilization.[25] The period known as the Ubaid period (c. 6500 to 3800 BC) is the earliest known period on the alluvial plain, although it is likely earlier periods exist obscured under the alluvium.[26][27] It was during the Ubaid period that the movement towards urbanization began. Agriculture and animal husbandry were widely practiced in sedentary communities, particularly in Northern Mesopotamia, and intensive irrigated hydraulic agriculture began to be practiced in the south.[28]

Around 6000 BC, Neolithic settlements appear all over Egypt.[29] Studies based on morphological,[30] genetic,[31][32][33][34][35] and archaeological data[36][37][38][39] have attributed these settlements to migrants from the Fertile Crescent in the Near East returning during the Egyptian and North African Neolithic Revolution and bringing agriculture to the region.

Eridu is the oldest Sumerian site settled during this period, around 5300 BC, and the city of Ur also first dates to the end of this period.[40] In the south, the Ubaid period had a very long duration from around 6500 to 3800 BC; when it is replaced by the Uruk period.[41]

Sumerian civilization coalesces in the subsequent Uruk period (4000 to 3100 BC).[42] Named after the Sumerian city of Uruk, this period saw the emergence of urban life in Mesopotamia and, during its later phase, the gradual emergence of the cuneiform script. Proto-writing in the region dates to around 3500 BC, with the earliest texts dating to 3300 BC; early cuneiform writing emerged in 3000 BC.[43] It was also during this period that pottery painting declined as copper started to become popular, along with cylinder seals.[44] Sumerian cities during the Uruk period were probably theocratic and were most likely headed by a priest-king (ensi), assisted by a council of elders, including both men and women.[45] It is quite possible that the later Sumerian pantheon was modeled upon this political structure. Uruk trade networks started to expand to other parts of Mesopotamia and as far as North Caucasus, and strong signs of governmental organization and social stratification began to emerge leading to the Early Dynastic Period (c. 2900 BC).[46][47][48] The Jemdet Nasr period, which is generally dated from 3100–2900 BC and succeeds the Uruk period, is known as one of the formative stages in the development of the cuneiform script. The oldest clay tablets come from Uruk and date to the late fourth millennium BC, slightly earlier than the Jemdet Nasr Period. By the time of the Jemdet Nasr Period, the script had already undergone a number of significant changes. It originally consisted of pictographs, but by the time of the Jemdet Nasr Period it was already adopting simpler and more abstract designs. It is also during this period that the script acquired its iconic wedge-shaped appearance.[49] At the end of the Jemdet Nasr period there was a major archaeologically attested river flood in Shuruppak and other parts of Mesopotamia. Polychrome pottery from a destruction level below the flood deposit has been dated to immediately before the Early Dynastic Period around 2900 BC.[50][51]

After the Early Dynastic period begins, there was a shift in control of the city-states from the temple establishment headed by council of elders led by a priestly "En" (a male figure when it was a temple for a goddess, or a female figure when headed by a male god)[52] towards a more secular Lugal (Lu = man, Gal = great) and includes such legendary patriarchal figures as Enmerkar, Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh—who are supposed to have reigned shortly before the historic record opens c. 2700 BC, when the now deciphered syllabic writing started to develop from the early pictograms. The center of Sumerian culture remained in southern Mesopotamia, even though rulers soon began expanding into neighboring areas, and neighboring Semitic groups adopted much of Sumerian culture for their own. The earliest ziggurats began near the end of the Early Dynastic Period, although architectural precursors in the form of raised platforms date back to the Ubaid period,.[53] The well-known Sumerian King List dates to the early second millennium BC. It consists of a succession of royal dynasties from different Sumerian cities, ranging back into the Early Dynastic Period. Each dynasty rises to prominence and dominates the region, only to be replaced by the next. The document was used by later Mesopotamian kings to legitimize their rule. While some of the information in the list can be checked against other texts such as economic documents, much of it is probably purely fictional, and its use as a historical document is limited.[48]

Eannatum, the Sumerian king of Lagash, established one of the first verifiable empires in history in 2500 BC.[54] The neighboring Elam, in modern Iran, was also part of the early urbanization during the Chalcolithic period.[55] Elamite states were among the leading political forces of the Ancient Near East.[56] The emergence of Elamite written records from around 3000 BC also parallels Sumerian history, where slightly earlier records have been found.[57][58] During the 3rd millennium BC, there developed a very intimate cultural symbiosis between the Sumerians and the Akkadians.[59] Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as a spoken language somewhere between the 3rd and the 2nd millennia BC.[60] The Semitic-speaking Akkadian empire emerged around 2350 BC under Sargon the Great.[46] The Akkadian Empire reached its political peak between the 24th and 22nd centuries BC. Under Sargon and his successors, the Akkadian language was briefly imposed on neighboring conquered states such as Elam and Gutium. After the fall of the Akkadian Empire and the overthrow of the Gutians, there was a brief reassertion of Sumerian dominance in Mesopotamia under the Third Dynasty of Ur.[61] After the final collapse of Sumerian hegemony in Mesopotamia around 2004 BC, the Semitic Akkadian people of Mesopotamia eventually coalesced into two major Akkadian-speaking nations: Assyria in the north, and, a few centuries later, Babylonia in the south.[62][62][63]

Ancient Egypt

The developed Neolithic cultures belonging to the phases Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (10,200 BC) and Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (7600 to 6000 BC) appeared in the fertile crescent and from there spread eastwards and westwards.[22] Contemporaneously, a grain-grinding culture using the earliest type of sickle blades had replaced the culture of hunters, fishers, and gathering people using stone tools along the Nile. Geological evidence and computer climate modeling studies also suggest that natural climate changes around 8000 BC began to desiccate the extensive pastoral lands of northern Africa, eventually forming the Sahara. Continued desiccation forced the early ancestors of the Egyptians to settle around the Nile more permanently and to adopt a more sedentary lifestyle.[64] The oldest fully developed neolithic culture in Egypt is Fayum A culture which began around 5500 B.C.

By about 5500 BC, small tribes living in the Nile valley had developed into a series of inter-related cultures as far south as Sudan, demonstrating firm control of agriculture and animal husbandry, and identifiable by their pottery and personal items, such as combs, bracelets, and beads. The largest of these early cultures in upper Southern Egypt was the Badari, which probably originated in the Western Desert; it was known for its high quality ceramics, stone tools, and use of copper.[65] The oldest known domesticated bovine in Africa are from Fayum dating to around 4400 BC.[66] The Badari cultures was followed by the Naqada culture, which brought a number of technological improvements.[67] As early as the first Naqada Period, Amratia, Egyptians imported obsidian from Ethiopia, used to shape blades and other objects from flakes.[68] By 3300 BC, just before the first Egyptian dynasty, Egypt was divided into two kingdoms, known as Upper Egypt to the south, and Lower Egypt to the north.[69]

Egyptian civilization begins during the second phase of the Naqda culture, known as the Gerzeh period, around 3500 BC and coalesces with the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt around 3150 BC.[70] Farming produced the vast majority of food; with increased food supplies, the populace adopted a much more sedentary lifestyle, and the larger settlements grew to cities of about 5,000 residents. It was in this time that the city dwellers started using mud brick to build their cities, and the use of the arch and recessed walls for decorative effect became popular.[71] Copper instead of stone was increasingly used to make tools[71] and weaponry.[72] Symbols on Gerzean pottery also resemble nascent Egyptian hieroglyphs.[73] Early evidence also exists of contact with the Near East, particularly Canaan and the Byblos coast, during this time.[74] Concurrent with these cultural advances, a process of unification of the societies and towns of the upper Nile River, or Upper Egypt, occurred. At the same time the societies of the Nile Delta, or Lower Egypt, also underwent a unification process. During his reign in Upper Egypt, King Narmer defeated his enemies on the Delta and merged both the Kingdom of Upper and Lower Egypt under his single rule.[75]

The Early Dynastic Period of Egypt immediately followed the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt. It is generally taken to include the First and Second Dynasties, lasting from the Naqada III archaeological period until about the beginning of the Old Kingdom, c. 2686 BC.[76] With the First Dynasty, the capital moved from Thinis to Memphis with a unified Egypt ruled by a god-king. The hallmarks of ancient Egyptian civilization, such as art, architecture and many aspects of religion, took shape during the Early Dynastic period. The strong institution of kingship developed by the pharaohs served to legitimize state control over the land, labour, and resources that were essential to the survival and growth of ancient Egyptian civilization.[77]

Major advances in architecture, art, and technology were made during the subsequent Old Kingdom, fueled by the increased agricultural productivity and resulting population, made possible by a well-developed central administration.[78] Some of ancient Egypt's crowning achievements, the Giza pyramids and Great Sphinx, were constructed during the Old Kingdom. Under the direction of the vizier, state officials collected taxes, coordinated irrigation projects to improve crop yield, drafted peasants to work on construction projects, and established a justice system to maintain peace and order. Along with the rising importance of a central administration there arose a new class of educated scribes and officials who were granted estates by the pharaoh in payment for their services. Pharaohs also made land grants to their mortuary cults and local temples, to ensure that these institutions had the resources to worship the pharaoh after his death. Scholars believe that five centuries of these practices slowly eroded the economic power of the pharaoh, and that the economy could no longer afford to support a large centralized administration.[76] As the power of the pharaoh diminished, regional governors called nomarchs began to challenge the supremacy of the pharaoh. This, coupled with severe droughts between 2200 and 2150 BC,[79] is assumed to have caused the country to enter the 140-year period of famine and strife known as the First Intermediate Period.[80]

Ancient India

.png)

One of the earliest Neolithic sites in the Indian subcontinent is Bhirrana along the ancient Ghaggar-Hakra (Saraswati) riverine system in the present day state of Haryana in India, dating to around 7600 BC.[81] Other early sites include Lahuradewa in the Middle Ganges region and Jhusi near the confluence of Ganges and Yamuna rivers, both dating to around 7000 BC.[82][83] The aceramic Neolithic at Mehrgarh lasts from 7000 to 5500 BC, with the ceramic Neolithic at Mehrgarh lasting up to 3300 BC; blending into the Early Bronze Age. Mehrgarh is one of the earliest sites with evidence of farming and herding in the Indian subcontinent.[84][85] It is likely that the culture centered around Mehrgarh migrated into the Indus Valley and became the Indus Valley Civilisation.[86] The earliest fortified town in the region is found at Rehman Dheri, dated 4000 BC in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa close to River Zhob Valley. Other fortified towns found to date are at Amri (3600–3300 BC), Kot Diji in Sindh, and at Kalibangan (3000 BC) at the Hakra River.[87][88][89][90]

The Indus Valley Civilisation starts around 3300 BC with what is referred to as the Early Harappan Phase (3300 to 2600 BC). The earliest examples of the Indus Script date to this period,[91][92] as well as the emergence of citadels representing centralised authority and an increasingly urban quality of life.[93] Trade networks linked this culture with related regional cultures and distant sources of raw materials, including lapis lazuli and other materials for bead-making. By this time, villagers had domesticated numerous crops, including peas, sesame seeds, dates, and cotton, as well as animals, including the water buffalo.[94][95]

2600 BC marks the Mature Harappan Phase during which Early Harappan communities turned into large urban centres including Harappa, Dholavira, Mohenjo-Daro, Lothal, Rupar, and Rakhigarhi, and more than 1,000 towns and villages, often of relatively small size.[96] Mature Harappans evolved new techniques in metallurgy and produced copper, bronze, lead, and tin and displayed advanced levels of engineering.[97] As seen in Harappa, Mohenjo-daro and the recently partially excavated Rakhigarhi, this urban plan included the world's first known urban sanitation systems: see hydraulic engineering of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Within the city, individual homes or groups of homes obtained water from wells. From a room that appears to have been set aside for bathing, waste water was directed to covered drains, which lined the major streets. Houses opened only to inner courtyards and smaller lanes. The house-building in some villages in the region still resembles in some respects the house-building of the Harappans.[98] The advanced architecture of the Harappans is shown by their impressive dockyards, granaries, warehouses, brick platforms, and protective walls. The massive walls of Indus cities most likely protected the Harappans from floods and may have dissuaded military conflicts.[99]

The people of the Indus Civilisation achieved great accuracy in measuring length, mass, and time. They were among the first to develop a system of uniform weights and measures. A comparison of available objects indicates large scale variation across the Indus territories. Their smallest division, which is marked on an ivory scale found in Lothal in Gujarat, was approximately 1.704 mm, the smallest division ever recorded on a scale of the Bronze Age. Harappan engineers followed the decimal division of measurement for all practical purposes, including the measurement of mass as revealed by their hexahedron weights.[100] These chert weights were in a ratio of 5:2:1 with weights of 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500 units, with each unit weighing approximately 28 grams, similar to the English Imperial ounce or Greek uncia, and smaller objects were weighed in similar ratios with the units of 0.871. However, as in other cultures, actual weights were not uniform throughout the area. The weights and measures later used in Kautilya's Arthashastra (4th century BC) are the same as those used in Lothal.[101]

Around 1800 BC, signs of a gradual decline began to emerge, and by around 1700 BC most of the cities had been abandoned. Suggested contributory causes for the localisation of the IVC include changes in the course of the river,[102] and climate change that is also signalled for the neighbouring areas of the Middle East.[103][104] As of 2016 many scholars believe that drought led to a decline in trade with Egypt and Mesopotamia contributing to the collapse of the Indus Civilisation.[105] The Ghaggar-Hakra system was rain-fed,[106][107][note 1][108][note 2] and water-supply depended on the monsoons. The Indus Valley climate grew significantly cooler and drier from about 1800 BC, linked to a general weakening of the monsoon at that time.[106] The Indian monsoon declined and aridity increased, with the Ghaggar-Hakra retracting its reach towards the foothills of the Himalaya,[106][109][110] leading to erratic and less extensive floods that made inundation agriculture less sustainable. Aridification reduced the water supply enough to cause the civilisation's demise, and to scatter its population eastward.[111][112][113][note 3] As the monsoons kept shifting south, the floods grew too erratic for sustainable agricultural activities. The residents then migrated towards the Ganges basin in the east, where they established smaller villages and isolated farms. However trade with the old cities did not flourish. The small surplus produced in these small communities did not allow development of trade, and the cities died out.[114] The Indo-Aryan peoples migrated into the Indus River Valley during this period and began the Vedic age of India.[115] The Indus Valley Civilisation did not disappear suddenly and many elements of the civilization continued in later Indian subcontinent and Vedic cultures.[116]

Other than the Indus valley civilization, many experts do believe that a civilization also arose in south India at the banks of river Kunti in the village of Vellinezhi.[117] As a result, Vellinezhi became the center for learning for various art forms such as Kathakali in the early 20th century.[118]

Ancient China

Drawing on archaeology, geology and anthropology, modern scholars do not see the origins of the Chinese civilization or history as a linear story but rather the history of the interactions of different and distinct cultures and ethnic groups that influenced each other's development.[119] The specific cultural regions that developed Chinese civilization were the Yellow River civilization, the Yangtze civilization, and Liao civilization. Early evidence for Chinese millet agriculture is dated to around 7000 BC,[120] with the earliest evidence of cultivated rice found at Chengtoushan near the Yangtze River, dated to 6500 BC. Chengtoushan may also be the site of the first walled city in China.[121] By the beginning of the Neolithic Revolution, the Yellow River valley began to establish itself as a center of the Peiligang culture which flourished from 7000 to 5000 BC, with evidence of agriculture, constructed buildings, pottery, and burial of the dead.[122] With agriculture came increased population, the ability to store and redistribute crops, and the potential to support specialist craftsmen and administrators.[123] Its most prominent site is Jiahu.[123] Some scholars have suggested that the Jiahu symbols (6600 BC) are the earliest form of proto-writing in China.[124] However, it is likely that they should not be understood as writing itself, but as features of a lengthy period of sign-use which led eventually to a fully-fledged system of writing.[125] Archaeologists believe that the Peiligang culture was egalitarian, with little political organization.

It would eventually evolve into the Yangshao culture (5000 to 3000 BC), and their stone tools were polished and highly specialized. They may also have practiced an early form of silkworm cultivation.[126] The main food of the Yangshao people was millet, with some sites using foxtail millet and others broom-corn millet, though some evidence of rice has been found. The exact nature of Yangshao agriculture, small-scale slash-and-burn cultivation versus intensive agriculture in permanent fields, is currently a matter of debate. Once the soil was exhausted, residents picked up their belongings, moved to new lands, and constructed new villages.[127] However, Middle Yangshao settlements such as Jiangzhi contain raised-floor buildings that may have been used for the storage of surplus grains. Grinding stones for making flour were also found.[128]

Later, Yangshao culture was superseded by the Longshan culture, which was also centered on the Yellow River from about 3000 to 1900 BC, its most prominent site being Taosi.[129] The population expanded dramatically during the 3rd millennium BC, with many settlements having rammed earth walls. It decreased in most areas around 2000 BC until the central area evolved into the Bronze Age Erlitou culture. The earliest bronze artifacts have been found in the Majiayao culture site (3100 to 2700 BC).[130][131]

Chinese civilization begins during the second phase of the Erlitou period (1900 to 1500 BC), with Erlitou considered the first state level society of East Asia.[132] There is considerable debate whether Erlitou sites correlate to the semi-legendary Xia dynasty. The Xia dynasty (2070 to 1600 BC) is the first dynasty to be described in ancient Chinese historical records such as the Bamboo Annals, first published more than a millennium later during the Western Zhou period. Although Xia is an important element in Chinese historiography, there is to date no contemporary written evidence to corroborate the dynasty. Erlitou saw an increase in bronze metallurgy and urbanization and was a rapidly growing regional center with palatial complexes that provide evidence for social stratification.[133] The Erlitou civilization is divided into four phases, each of roughly 50 years. During Phase I, covering 100 hectares (250 acres), Erlitou was a rapidly growing regional center with estimated population of several thousand[134] but not yet an urban civilization or capital.[135] Urbanization began in Phase II, expanding to 300 ha (740 acres) with a population around 11,000.[134] A palace area of 12 ha (30 acres) was demarcated by four roads. It contained the 150x50 m Palace 3, composed of three courtyards along a 150-meter axis, and Palace 5.[136] A bronze foundry was established to the south of the palatial complex that was controlled by the elite who lived in palaces.[137] The city reached its peak in Phase III, and may have had a population of around 24,000.[135] The palatial complex was surrounded by a two-meter-thick rammed-earth wall, and Palaces 1, 7, 8, 9 were built. The earthwork volume of rammed earth for the base of largest Palace 1 is 20,000 m³ at least.[138] Palaces 3 and 5 were abandoned and replaced by 4,200-square-kilometer (4.5×1010 sq ft) Palace 2 and Palace 4.[139] In Phase IV, the population decreased to around 20,000, but building continued. Palace 6 was built as an extension of Palace 2, and Palaces 10 and 11 were built. Phase IV overlaps with the Lower phase of the Erligang culture (1600–1450 BC). Around 1600 to 1560 BC, about 6 km northeast of Erlitou, Eligang cultural walled city was built at Yanshi,[139] which coincides with an increase in production of arrowheads at Erlitou.[134] This situation might indicate that the Yanshi City was competing for power and dominance with Erlitou.[134] Production of bronzes and other elite goods ceased at the end of Phase IV, at the same time as the Erligang city of Zhengzhou was established 85 km (53 mi) to the east. There is no evidence of destruction by fire or war, but, during the Upper Erligang phase (1450–1300 BC), all the palaces were abandoned, and Erlitou was reduced to a village of 30 ha (74 acres).[139]

The earliest traditional Chinese dynasty for which there is both archeological and written evidence is the Shang dynasty (1600 to 1046 BC). Shang sites have yielded the earliest known body of Chinese writing, the oracle bone script, mostly divinations inscribed on bones. These inscriptions provide critical insight into many topics from the politics, economy, and religious practices to the art and medicine of this early stage of Chinese civilization.[140] Some historians argue that Erlitou should be considered an early phase of the Shang dynasty. The U.S. National Gallery of Art defines the Chinese Bronze Age as the period between about 2000 and 771 BC; a period that begins with the Erlitou culture and ends abruptly with the disintegration of Western Zhou rule.[141] The Sanxingdui culture is another Chinese Bronze Age society, contemporaneous to the Shang dynasty, however they developed a different method of bronze-making from the Shang.[142]

Andes

The earliest evidence of agriculture in the Andean region dates to around 4700 BC at Huaca Prieta and Paredones.[143][144][145] The oldest evidence of canal irrigation in South America dates to 4700 to 2500 BC in the Zaña Valley of northern Peru.[146] The earliest urban settlements of the Andes, as well as North and South America, are dated to 3500 BC at Huaricanga, in the Fortaleza area,[4] and Sechin Bajo near the Sechin River.[147][148]

The Norte Chico civilization proper is understood to have emerged around 3200 BC, as it is at that point that large-scale human settlement and communal construction across multiple sites becomes clearly apparent.[149] Since the early 21st century, it has been established as the oldest known civilization in the Americas. The civilization flourished at the confluence of three rivers, the Fortaleza, the Pativilca, and the Supe. These river valleys each have large clusters of sites. Further south, there are several associated sites along the Huaura River.[150] Notable settlements include the cities of Caral, the largest and most complex Preceramic site, and Aspero.[151] Norte Chico sites are known for their density of large sites with immense architecture.[152] Haas argues that the density of sites in such a small area is globally unique for a nascent civilization. During the third millennium BC, Norte Chico may have been the most densely populated area of the world (excepting, possibly, northern China).[153] The Supe, Pativilca, Fortaleza, and Huaura River valleys each have several related sites.

Norte Chico is unusual in that it completely lacked ceramics and apparently had almost no visual art. Nevertheless, the civilization exhibited impressive architectural feats, including large earthwork platform mounds and sunken circular plazas, and an advanced textile industry.[4][154] The platform mounds, as well as large stone warehouses, provide evidence for a stratified society and a centralized authority necessary to distribute resources such as cotton.[4] However, there is no evidence of warfare or defensive structures during this period.[153] Originally, it was theorized that, unlike other early civilizations, Norte Chico developed by relying on maritime food sources in place of a staple cereal. This hypothesis, the Maritime Foundation of Andean Civilization, is still hotly debated; however, most researches now agree that agriculture played a central role in the civilization's development while still acknowledging a strong supplemental reliance on maritime proteins.[155][156][157]

The Norte Chico chiefdoms were "almost certainly theocratic, though not brutally so", according to Mann. Construction areas show possible evidence of feasting, which would have included music and likely alcohol, suggesting an elite able to both mobilize and reward the population.[4] The degree of centralized authority is difficult to ascertain, but architectural construction patterns are indicative of an elite that, at least in certain places at certain times, wielded considerable power: while some of the monumental architecture was constructed incrementally, other buildings, such as the two main platform mounds at Caral, appear to have been constructed in one or two intense construction phases.[153] As further evidence of centralized control, Haas points to remains of large stone warehouses found at Upaca, on the Pativilca, as emblematic of authorities able to control vital resources such as cotton.[4] Economic authority would have rested on the control of cotton and edible plants and associated trade relationships, with power centered on the inland sites. Haas tentatively suggests that the scope of this economic power base may have extended widely: there are only two confirmed shore sites in the Norte Chico (Aspero and Bandurria) and possibly two more, but cotton fishing nets and domesticated plants have been found up and down the Peruvian coast. It is possible that the major inland centers of Norte Chico were at the center of a broad regional trade network centered on these resources.[153]

Discover magazine, citing Shady, suggests a rich and varied trade life: "[Caral] exported its own products and those of Aspero to distant communities in exchange for exotic imports: Spondylus shells from the coast of Ecuador, rich dyes from the Andean highlands, hallucinogenic snuff from the Amazon."[158] (Given the still limited extent of Norte Chico research, such claims should be treated circumspectly.) Other reports on Shady's work indicate Caral traded with communities in the Andes and in the jungles of the Amazon basin on the opposite side of the Andes.[159]

Leaders' ideological power was based on apparent access to deities and the supernatural.[153] Evidence regarding Norte Chico religion is limited: an image of the Staff God, a leering figure with a hood and fangs, has been found on a gourd dated to 2250 BC. The Staff God is a major deity of later Andean cultures, and Winifred Creamer suggests the find points to worship of common symbols of gods.[160][161] As with much other research at Norte Chico, the nature and significance of the find has been disputed by other researchers.[note 4] The act of architectural construction and maintenance may also have been a spiritual or religious experience: a process of communal exaltation and ceremony.[151] Shady has called Caral "the sacred city" (la ciudad sagrada): socio-economic and political focus was on the temples, which were periodically remodeled, with major burnt offerings associated with the remodeling.[162]

The discovery of quipu, string-based recording devices, at Caral can be understood as a form of "proto-writing" at Norte Chico.[163] However, the exact use of quipu in this and later Andean cultures has been widely debated.[4] Additionally, the image of the Staff God has been found on a gourd dated to 2250 BC. The Staff God is a major deity of later Andean cultures. The presence of quipu and the commonality of religious symbols suggests a cultural link between Norte Chico and later Andean cultures.[160][161]

Circa 1800 BC, the Norte Chico civilization began to decline, with more powerful centers appearing to the south and north along the coast and to the east inside the belt of the Andes.[164] Pottery eventually developed in the Amazon Basin and spread to the Andean culture region around 2000 BC. The next major civilization to arise in the Andes would be the Chavín culture at Chavín de Huantar, located in the Andean highlands of the present-day Ancash Region. It is believed to have been built around 900 BC and was the religious and political center of the Chavín people.[165]

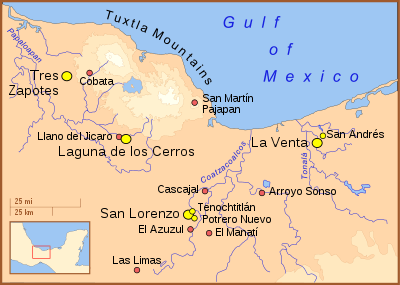

Mesoamerica

The Coxcatlan caves in the Valley of Tehuacán provide evidence for agriculture in components dated between 5000 and 3400 BC.[166] Similarly, sites such as Sipacate in Guatemala provide maize pollen samples dating to 3500 BC.[167] It is estimated that fully domesticated maize developed in Mesoamerica around 2700 BC.[168] Mesoamericans during this period likely divided their time between small hunting encampments and large temporary villages.[169] Around 1900 BC, the Mokaya domesticated one of the dozen species of cacao.[170][171] A Mokaya archaeological site provides evidence of cacao beverages dating to this time.[172] The Mokaya are also thought to have been among the first cultures in Mesoamerica to develop a hierarchical society. What would become the Olmec civilization had its roots in early farming cultures of Tabasco, which began around 5100 to 4600 BC.[173]

The emergence of the Olmec civilization has traditionally been dated to around 1600 to 1500 BC. Olmec features first emerged in the city of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, fully coalescing around 1400 BC. The rise of civilization was assisted by the local ecology of well-watered alluvial soil, as well as by the transportation network provided by the Coatzacoalcos River basin.[173] This environment encouraged a densely concentrated population, which in turn triggered the rise of an elite class and an associated demand for the production of the symbolic and sophisticated luxury artifacts that define Olmec culture.[174] Many of these luxury artifacts were made from materials such as jade, obsidian, and magnetite, which came from distant locations and suggest that early Olmec elites had access to an extensive trading network in Mesoamerica. The aspect of Olmec culture perhaps most familiar today is their artwork, particularly the Olmec colossal heads.[175] San Lorenzo was situated in the midst of a large agricultural area.[176] San Lorenzo seems to have been largely a ceremonial site, a town without city walls, centered in the midst of a widespread medium-to-large agricultural population. The ceremonial center and attendant buildings could have housed 5,500 while the entire area, including hinterlands, could have reached 13,000.[177] It is thought that while San Lorenzo controlled much or all of the Coatzacoalcos basin, areas to the east (such as the area where La Venta would rise to prominence) and north-northwest (such as the Tuxtla Mountains) were home to independent polities.[178] San Lorenzo was all but abandoned around 900 BC at about the same time that La Venta rose to prominence. A wholesale destruction of many San Lorenzo monuments also occurred circa 950 BC, which may indicate an internal uprising or, less likely, an invasion.[179] The latest thinking, however, is that environmental changes may have been responsible for this shift in Olmec centers, with certain important rivers changing course.[180]

La Venta became the cultural capital of the Olmec concentration in the region until its abandonment around 400 BC; constructing monumental architectural achievements such as the Great Pyramid of La Venta.[173][175] It contained a “concentration of power,” as reflected by the sheer enormity of the architecture and the extreme value of the artifacts uncovered.[181] La Venta is perhaps the largest Olmec city and it was controlled and expanded by an extremely complex hierarchical system with a king, as the ruler and the elites below him. Priests had power and influence over life and death and likely great political sway as well. Unfortunately, not much is known about the political or social structure of the Olmec, though new dating techniques might, at some point, reveal more information about this elusive culture. It is possible that the signs of status exist in the artifacts recovered at the site such as depictions of feathered headdresses or of individuals wearing a mirror on their chest or forehead.[182] “High-status objects were a significant source of power in the La Venta polity political power, economic power, and ideological power. They were tools used by the elite to enhance and maintain rights to rulership.”[183] It has been estimated that La Venta would need to be supported by a population of at least 18,000 people during its principal occupation.[184] To add to the mystique of La Venta, the alluvial soil did not preserve skeletal remains, so it is difficult to observe differences in burials. However, colossal heads provide proof that the elite had some control over the lower classes, as their construction would have been extremely labor-intensive. “Other features similarly indicate that many laborers were involved.”[185] In addition, excavations over the years have discovered that different parts of the site were likely reserved for elites and other parts for non-elites. This segregation of the city indicates that there must have been social classes and therefore social inequality.[182] The exact cause of the decline of the Olmec culture is uncertain. Between 400 and 350 BC, the population in the eastern half of the Olmec heartland dropped precipitously.[186] This depopulation was probably the result of serious environmental changes that rendered the region unsuited for large groups of farmers, in particular changes to the riverine environment that the Olmec depended upon for agriculture, hunting and gathering, and transportation. These changes may have been triggered by tectonic upheavals or subsidence, or the silting up of rivers due to agricultural practices.[173][175] Within a few hundred years of the abandonment of the last Olmec cities, successor cultures became firmly established. The Tres Zapotes site, on the western edge of the Olmec heartland, continued to be occupied well past 400 BC, but without the hallmarks of the Olmec culture. This post-Olmec culture, often labeled Epi-Olmec, has features similar to those found at Izapa, some 550 km (330 miles) to the southeast.[187]

The Olmecs are sometimes referred to as the mother culture of Mesoamerica, as they were the first Mesoamerican civilization and laid many of the foundations for the civilizations that followed.[188] However, the causes and degree of Olmec influences on Mesoamerican cultures has been a subject of debate over many decades.[189] Practices introduced by the Olmec include ritual bloodletting and the Mesoamerican ballgame; hallmarks of subsequent Mesoamerican societies such as the Maya and Aztec.[188] Although the Mesoamerican writing system would fully develop later, early Olmec ceramics show representations that may be interpreted as codices.[173]

Cradle of Western civilization

There is academic consensus that Classical Greece is the seminal culture which provided the foundation of modern Western culture, democracy, art, theatre, philosophy and science. For this reason it is known as the cradle of Western Civilization.[lower-alpha 1] Along with Greece, Rome has sometimes been described as a birthplace or as the cradle of Western Civilization because of the role the city had in politics, republicanism, law, architecture, warfare and Western Christianity.[lower-alpha 2]

Timeline

The following timeline shows the approximate dates of the emergence of civilization (as discussed in the article) in the featured areas and the primary cultures associated with these early civilizations. It is important to note that the timeline is not indicative of the beginning of human habitation, the start of a specific ethnic group, or the development of Neolithic cultures in the area – any of which often occurred significantly earlier than the emergence of civilization proper.

Notes

- Geological research by a group led by Peter Clift investigated how the courses of rivers have changed in this region since 8000 years ago, to test whether climate or river reorganisations caused the decline of the Harappan. Using U-Pb dating of zircon sand grains they found that sediments typical of the Beas, Sutlej and Yamuna rivers (Himalayan tributaries of the Indus) are actually present in former Ghaggar-Hakra channels. However, sediment contributions from these glacial-fed rivers stopped at least by 10,000 years ago, well before the development of the Indus civilisation.[107]

- Tripathi et al. (2004) found that the isotopes of sediments carried by the Ghaggar-Hakra system over the last 20 thousand years do not come from the glaciated Higher Himalaya but have a sub-Himalayan source, and concluded that the river system was rain-fed. They also concluded that this contradicted the idea of a Harappan-time mighty "Sarasvati" river.[108]

- Broke:[113] "The story in Harappan India was somewhat different (see Figure 111.3). The Bronze Age village and urban societies of the Indus Valley are some-thing of an anomaly, in that archaeologists have found little indication of local defense and regional warfare. It would seem that the bountiful monsoon rainfall of the Early to Mid-Holocene had forged a condition of plenty for all, and that competitive energies were channeled into commerce rather than conflict. Scholars have long argued that these rains shaped the origins of the urban Harappan societies, which emerged from Neolithic villages around 2600 BC. It now appears that this rainfall began to slowly taper off in the third millennium, at just the point that the Harappan cities began to develop. Thus it seems that this "first urbanisation" in South Asia was the initial response of the Indus Valley peoples to the beginning of Late Holocene aridification. These cities were maintained for 300 to 400 years and then gradually abandoned as the Harappan peoples resettled in scattered villages in the eastern range of their territories, into the Punjab and the Ganges Valley....'

17 (footnote):

a)Liviu Giosan et al., "Fluvial Landscapes of the Harappan Civilization," PNAS, 102 (2012), E1688—E1694;

(b) Camilo Ponton, "Holocene Aridification of India," GRL 39 (2012), L03704;

(c) Harunur Rashid et al., "Late Glacial to Holocene Indian Summer Monsoon Variability Based upon Sediment Records Taken from the Bay of Bengal," Terrestrial, Atmospheric, and Oceanic Sciences 22 (2011), 215–28;

(d) Marco Madella and Dorian Q. Fuller, "Paleoecology and the Harappan Civilization of South Asia: A Reconsideration," Quaternary Science Reviews 25 (2006), 1283–301. Compare with the very different interpretations in Possehl, Gregory L. (2002), The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective, Rowman Altamira, pp. 237–245, ISBN 978-0-7591-0172-2, and Michael Staubwasser et al., "Climate Change at the 4.2 ka BP Termination of the Indus Valley Civilization and Holocene South Asian Monsoon Variability," GRL 30 (2003), 1425. Bar-Matthews and Avner Ayalon, "Mid-Holocene Climate Variations." - Krysztof Makowski, as reported by Mann (1491), suggests there is little evidence that Andean civilizations worshipped an overarching deity. The figure may have been carved by a later civilization onto an ancient gourd, as it was found in strata dating between 900 and 1300 AD.

References

Citations

- Charles Keith Maisels (1993). The Near East: Archaeology in the "Cradle of Civilization. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-04742-5.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early medieval India : from the Stone Age to the 12th century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. p. 137. ISBN 9788131711200.

- Cradles of Civilization-China: Ancient Culture, Modern Land, Robert E. Murowchick, gen. ed. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994

- Mann, Charles C. (2006) [2005]. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Vintage Books. pp. 199–212. ISBN 978-1-4000-3205-1.

- Haviland, William; et al. (2013). Cultural Anthropology: The Human Challenge. Cengage Learning. p. 250. ISBN 978-1285675305.

- Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Study, Trigger, Bruce G., Cambridge University Press, 2007

- Maura Ellyn; Maura McGinnis (2004). Greece: A Primary Source Cultural Guide. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-8239-3999-2.

- Lin (林), Shengyi (勝義); He (何), Xianrong (顯榮) (2001). 臺灣--人類文明原鄉 [Taiwan — The Cradle of Civilization]. Taiwan gu wen ming yan jiu cong shu (臺灣古文明研究叢書) (in Chinese). Taipei: Taiwan fei die xue yan jiu hui (台灣飛碟學硏究會). ISBN 978-957-30188-0-3. OCLC 52945170.

- Ofer Bar-Yosef. "The Natufian Culture in the Levant, Threshold to the Origins of Agriculture" (PDF). Columbia.edu. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- La protohistoire de l'Europe, Jan Lichardus et al., Presses Universitaires de France, Paris. ISBN 84-335-9366-8, 1987, chapter II.2.

- Carr, Edward H. (1961). What is History?, p. 108, ISBN 0-14-020652-3.

- Britannica 15th edition, 26:62–63.

- "The Rise Of Civilization In The Middle East And Africa". History-world.org. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- "Rise of Civilizations: Mesopotamia to Mesoamerica", Archaeology, Wright, Henry T., vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 46–48, 96–100, 1990

- "AP World History". College Board. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- "World History Course Description" (PDF). College Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- "Civilization". The Columbia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- Edwin, Eric (27 February 2015). "city". Britannica.com. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- "Africanafrican.com" (PDF). Africanafrican.com. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- The Ancient Hawaiian State: Origins of a Political Society, Hommon, Robert J., Oxford University Press, 2013

- Kennett, Douglas J.; Winterhalder, Bruce (2006). Behavioral Ecology and the Transition to Agriculture. University of California Press. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-0-520-24647-8. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- Bellwood, Peter. First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies. 2004. Wiley-Blackwell

- Akhilesh Pillalamarri (18 April 2015). "Exploring the Indus Valley's Secrets". The diplomat. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- "Jericho – Facts & History".

- "Ubaid Civilization". Ancientneareast.tripod.com. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- Adams, Robert MCC. and Wright, Henry T. 1989. 'Concluding Remarks' in Henrickson, Elizabeth and Thuesen, Ingolf (eds.) Upon This Foundation – The ’Ubaid Reconsidered. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 451–456.

- Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East (Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, Number 63) The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (2010) ISBN 978-1-885923-66-0 p.2, at http://oi.uchicago.edu/research/pubs/catalog/saoc/saoc63.html; "Radiometric data suggest that the whole Southern Mesopotamian Ubaid period, including Ubaid 0 and 5, is of immense duration, spanning nearly three millennia from about 6500 to 3800 B.C".

- Pollock, Susan (1999). Ancient Mesopotamia: The Eden that Never Was. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57334-4.

- Redford, Donald B (1992). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton: University Press. p. 6.

- Brace, C. Loring; Seguchi, Noriko; Quintyn, Conrad B.; Fox, Sherry C.; Nelson, A. Russell; Manolis, Sotiris K.; Qifeng, Pan (2006). "The questionable contribution of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age to European craniofacial form". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (1): 242–247. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..242B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509801102. PMC 1325007. PMID 16371462.

- Chicki, L; Nichols, RA; Barbujani, G; Beaumont, MA (2002). "Y genetic data support the Neolithic demic diffusion model". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99 (17): 11008–11013. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9911008C. doi:10.1073/pnas.162158799. PMC 123201. PMID 12167671.

- "Estimating the Impact of Prehistoric Admixture on the Genome of Europeans, Dupanloup et al., 2004". Mbe.oxfordjournals.org. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- Semino, O; Magri, C; Benuzzi, G; et al. (May 2004). "Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area, 2004". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74 (5): 1023–34. doi:10.1086/386295. PMC 1181965. PMID 15069642.

- Cavalli-Sforza (1997). "Paleolithic and Neolithic lineages in the European mitochondrial gene pool". Am J Hum Genet. 61 (1): 247–54. doi:10.1016/S0002-9297(07)64303-1. PMC 1715849. PMID 9246011. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- Chikhi (21 July 1998). "Clines of nuclear DNA markers suggest a largely Neolithic ancestry of the European gene". PNAS. 95 (15): 9053–9058. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.9053C. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.15.9053. PMC 21201. PMID 9671803. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- Zvelebil, M. (1986). Hunters in Transition: Mesolithic Societies and the Transition to Farming. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–15, 167–188.

- Bellwood, P. (2005). First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Dokládal, M.; Brožek, J. (1961). "Physical Anthropology in Czechoslovakia: Recent Developments". Current Anthropology. 2 (5): 455–477. doi:10.1086/200228.

- Zvelebil, M. (1989). "On the transition to farming in Europe, or what was spreading with the Neolithic: a reply to Ammerman (1989)". Antiquity. 63 (239): 379–383. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00076110.

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2002), "Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City" (Penguin)

- Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham. 2010. 'Deconstructing the Ubaid' in Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham (eds.) Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. p. 2.

- Crawford, Harriet E. W. Sumer and the Sumerians. Cambridge University Press. 2nd ed. 2004

- Cuneiform ancient.eu

- An Encyclopedia of World History. Langer, William L. ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. Boston, MA. 1972

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (Ed) (1939),"The Sumerian King List" (Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago; Assyriological Studies, No. 11., 1939)

- Pruß, Alexander (2004), "Remarks on the Chronological Periods", in Lebeau, Marc; Sauvage, Martin (eds.), Atlas of Preclassical Upper Mesopotamia, Subartu, 13, pp. 7–21, ISBN 978-2503991207

- Postgate, J.N. (1992), Early Mesopotamia. Society and Economy at the Dawn of History, London: Routledge, ISBN 9780415110327

- van de Mieroop, M. (2007), A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000-323 BC, Malden: Blackwell, ISBN 978-0631225522

- Woods 2010, pp. 36–37

- Schmidt (1931).

- Martin (1988), pp. 20–23.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1976), "The Harps that Once...; Sumerian Poetry in Translation" and "Treasures of Darkness: a history of Mesopotamian Religion"

- Crawford, page 73-74

- Kleiner, Fred S.; Mamiya, Christin J. (2006). Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective — Volume 1 (12th ed.). Belmont, California, USA: Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-495-00479-0.

- The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State – by D. T. Potts, Cambridge University Press, 29 July 1999 – page 46 – ISBN 0521563585 hardback

- Elam: surveys of political history and archaeology, Elizabeth Carter and Matthew W. Stolper, University of California Press, 1984, p. 3

- Hock, Hans Heinrich (2009). Language History, Language Change, and Language Relationship: An Introduction to Historical and Comparative Linguistics (2nd ed.). Mouton de Gruyter. p. 69. ISBN 978-3110214291.

- Gnanadesikan, Amalia (2008). The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet. Blackwell. p. 25. ISBN 978-1444304688.

- Deutscher, Guy (2007). Syntactic Change in Akkadian: The Evolution of Sentential Complementation. Oxford University Press US. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-19-953222-3.

- Woods, C. (2006). "Bilingualism, Scribal Learning, and the Death of Sumerian" (PDF). S.L. Sanders (ed) Margins of Writing, Origins of Culture: 91–120. Chicago.

- Samuel Noah Kramer (17 September 2010). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-45238-8.

- J. M. Munn-Rankin (1975). "Assyrian Military Power, 1300–1200 B.C.". In I. E. S. Edwards (ed.). Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 2, Part 2, History of the Middle East and the Aegean Region, c. 1380–1000 BCE. Cambridge University Press. pp. 287–288, 298.

- Christopher Morgan (2006). Mark William Chavalas (ed.). The ancient Near East: historical sources in translation. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 145–152.

- Barich et al. (1984) Ecological and Cultural Relevance of the Recent New Radiocabon dates from Libyan Sahara. In: L. Krzyzaniak and M. Kobusiewicz [eds.], Origin and Early Development of Food-Producing Cultures in Northeastern Africa, Poznan, Poznan Archaeological Museum, pp. 411–17.

- Hayes, W. C. (October 1964). "Most Ancient Egypt: Chapter III. The Neolithic and Chalcolithic Communities of Northern Egypt". JNES (No. 4 ed.) 23 (4): 217–272

- Barich, B. E. (1998) People, Water and Grain: The Beginnings of Domestication in the Sahara and the Nile Valley. Roma: L' Erma di Bretschneider (Studia archaeologica 98).

- Childe, V. Gordon (1953), New Light on the Most Ancient Near East, (Praeger Publications)

- Barbara G. Aston, James A. Harrell, Ian Shaw (2000). Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw editors. "Stone," in Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology, Cambridge, 5–77, pp. 46–47. Also note: Barbara G. Aston (1994). "Ancient Egyptian Stone Vessels," Studien zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altägyptens 5, Heidelberg, pp. 23–26. (See on-line posts: and .)

- Adkins, L. and Adkins, R. (2001) The Little Book of Egyptian Hieroglyphics, p155. London: Hodder and Stoughton

- Shaw, Ian, ed. (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 479. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992)

- Gardiner, Alan H. Egypt of the Pharaohs: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. 1964

- Adkins, L.; Adkins, R (2001). The Little Book of Egyptian Hieroglyphics. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Patai, Raphael (1998), Children of Noah: Jewish Seafaring in Ancient Times (Princeton Uni Press)

- Roebuck, Carl (1966). The World of Ancient Times. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons Publishing.

- Shaw, Ian (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press

- "Early Dynastic Egypt". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. Archived from the original on 4 March 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- James (2005) p. 40

- Fekri Hassan. "The Fall of the Old Kingdom". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 10 March 2008.

- Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. London, England: Thames and Hudson.

- "Haryana's Bhirrana oldest Harappan site, Rakhigarhi Asia's largest: ASI". Times of India. 15 April 2015.

- Fuller, Dorian (2006). "Agricultural Origins and Frontiers in South Asia: A Working Synthesis" (PDF). Journal of World Prehistory. 20: 42.

- Tewari, Rakesh et al. 2006. "Second Preliminary Report of the excavations at Lahuradewa, District Sant Kabir Nagar, UP 2002-2003-2004 & 2005–06" in Pragdhara No. 16 "Electronic Version p.28" Archived 28 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- UNESCO World Heritage. 2004. ". Archaeological Site of Mehrgarh

- Hirst, K. Kris. 2005. "Mehrgarh". Guide to Archaeology

- Parpol, Asko. 2015. The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilisation. Oxford University Press

- Charles Keith Maisels, Early Civilizations of the Old World: The Formative Histories of Egypt, The Levant, Mesopotamia, India and China. Routledge, 2003 ISBN 1134837305

- Higham, Charles (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations. Infobase Publishing. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-1-4381-0996-1.

- Sigfried J. de Laet, Ahmad Hasan Dani, eds. History of Humanity: From the third millennium to the seventh century B.C. UNESCO, 1996 ISBN 9231028111 p.674

- Garge, Tejas (2010). "Sothi-Siswal Ceramic Assemblage: A Reappraisal". Ancient Asia. 2: 15. doi:10.5334/aa.10203.

- Peter T. Daniels. The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University. p. 372.

- Parpola, Asko (1994). Deciphering the Indus Script. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43079-1.

- Thapar, B. K. (1975). "Kalibangan: A Harappan Metropolis Beyond the Indus Valley". Expedition. 17 (2): 19–32.

- Valentine, Benjamin; Kamenov, George D.; Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark; Shinde, Vasant; Mushrif-Tripathy, Veena; Otarola-Castillo, Erik; Krigbaum, John (2015). "Evidence for Patterns of Selective Urban Migration in the Greater Indus Valley (2600–1900 BC): A Lead and Strontium Isotope Mortuary Analysis". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0123103. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1023103V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123103. PMC 4414352. PMID 25923705.

- "Indus Valley people migrated from villages to cities: New study".

- "Indus re-enters India after two centuries, feeds Little Rann, Nal Sarovar". India Today. 7 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Pruthi, Raj (2004). Prehistory and Harappan Civilization. APH Publishing. p. 260. ISBN 9788176485814.

- It has been noted that the courtyard pattern and techniques of flooring of Harappan houses has similarities to the way house-building is still done in some villages of the region. Lal 2002, pp. 93–95

- Morris, A.E.J. (1994). History of Urban Form: Before the Industrial Revolutions (Third ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-582-30154-2. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Feuerstein, Georg; Kak, Subhash; Frawley, David (2001). In Search of the Cradle of Civilization:New Light on Ancient India. Quest Books. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8356-0741-4.

- Sergent, Bernard (1997). Genèse de l'Inde (in French). Paris: Payot. p. 113. ISBN 978-2-228-89116-5.

- David Knipe (1991), Hinduism. San Francisco: Harper

- "Decline of Bronze Age 'megacities' linked to climate change".

- Emma Maris (2014), Two-hundred-year drought doomed Indus Valley Civilization, nature

- "Indus Collapse: The End or the Beginning of an Asian Culture?". Science Magazine. 320: 1282–3. 6 June 2008.

- Giosan, L.; et al. (2012). "Fluvial landscapes of the Harappan Civilization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 109 (26): E1688–94. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109E1688G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112743109. PMC 3387054. PMID 22645375.

- Clift et al., 2011, U-Pb zircon dating evidence for a Pleistocene Sarasvati River and capture of the Yamuna River, Geology, 40, 211–214 (2011).

- Tripathi, Jayant K.; Tripathi, K.; Bock, Barbara; Rajamani, V. & Eisenhauer, A. (25 October 2004). "Is River Ghaggar, Saraswati? Geochemical Constraints" (PDF). Current Science. 87 (8). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2004.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Rachel Nuwer (28 May 2012). "An Ancient Civilization, Upended by Climate Change". LiveScience. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- Charles Choi (29 May 2012). "Huge Ancient Civilization's Collapse Explained". New York Times. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- Madella, Marco; Fuller, Dorian (2006). "Palaeoecology and the Harappan Civilisation of South Asia: a reconsideration". Quaternary Science Reviews. 25 (11–12): 1283–1301. Bibcode:2006QSRv...25.1283M. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.10.012.

- MacDonald, Glen (2011). "Potential influence of the Pacific Ocean on the Indian summer monsoon and Harappan decline". Quaternary International. 229 (1–2): 140–148. Bibcode:2011QuInt.229..140M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2009.11.012.

- Brooke, John L. (2014), Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey, Cambridge University Press, p. 296, ISBN 978-0-521-87164-8

- Thomas H. Maugh II (28 May 2012). "Migration of monsoons created, then killed Harappan civilization". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- Edwin Bryant (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture. pp. 159–60

- White, David Gordon (2003). Kiss of the Yogini. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-226-89483-6.

- "Vellinezhi - a hamlet on the banks of Kunthipuzha in Palakkad". Kerala Tourism. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "Vellinezhi art village in Palakkad oozes old-world charm". OnManorama. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- Ebrey, Patricia (2006). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge University Press. pp. 12–18. ISBN 978-0-521-43519-2.

- "Rice and Early Agriculture in China". Legacy of Human Civilizations. Mesa Community College. Archived from the original on 27 August 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- http://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/handle/10125/17124/AP-v38n2-119-153.pdf?sequence=1

- "Peiligang Site". Ministry of Culture of the People's Republic of China. 2003. Archived from the original on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- Pringle, Heather (1998). "The Slow Birth of Agriculture". Science. 282 (5393): 1446. doi:10.1126/science.282.5393.1446. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011.

- Rincon, Paul (17 April 2003). "'Earliest writing' found in China". BBC News.

- Li, X; Harbottle, Garman; Zhang Juzhong; Wang Changsui (2003). "The earliest writing? Sign use in the seventh millennium BCE at Jiahu, Henan Province, China". Antiquity. 77 (295): 31–44. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00061329.

- Chang (1986), p. 113.

- Pollard, Elizabeth (2015). Worlds Together Worlds Apart. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-393-91847-2.

- Chang (1986), p. 112.

- Wertz, Richard R. (2007). "Neolithic and Bronze Age Cultures". Exploring Chinese History. ibiblio. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- Martini, I. Peter (2010). Landscapes and Societies: Selected Cases. Springer. p. 310. ISBN 978-90-481-9412-4.

- Higham, Charles (2004). Encyclopedia of ancient Asian civilizations. Infobase Publishing. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-8160-4640-9.

- Archived 21 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Liu, L. & Xiu, H., "Rethinking Erlitou: legend, history and Chinese archaeology", Antiquity, 81:314 (2007)

- Liu 2006, p. 184.

- Liu 2004, p. 229.

- Li 2003.

- Liu 2004, pp. 230–231.

- "二里头:华夏王朝文明的开端". 寻根. 3.

- Liu & Xu 2007.

- Howells, William (1983). "Origins of the Chinese People: Interpretations of recent evidence". In Keightley, David N. (ed.). The Origins of Chinese Civilization. University of California Press. pp. 297–319. ISBN 978-0-520-04229-2.

- "Teaching Chinese Archaeology, Part Two — NGA". Nga.gov. Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- Sanxingdui Museum (2006)

- "Popcorn Was Popular in Ancient Peru, Discovery Suggests". History.com. 20 January 2012. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013.

- "Study suggests ancient Peruvians 'ate popcorn'". BBC News. 19 January 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- Grobman, A.; Bonavia, D.; Dillehay, T. D.; Piperno, D. R.; Iriarte, J.; Holst, I. (2012). "Preceramic maize from Paredones and Huaca Prieta, Peru". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (5): 1755–9. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.1755G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1120270109. PMC 3277113. PMID 22307642.

- Dillehay, Tom D.; Eling Jr., Herbert H.; Rossen, Jack (2005). "Preceramic Irrigation Canals in the Peruvian Andes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (47): 17241–44. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10217241D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0508583102. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1288011. PMID 16284247.

- "Oldest Urban Site in the Americas Found, Experts Claim", National Geographic News, 26 February 2008, , accessed 20 January 2016

- "Ancient ceremonial plaza found in Peru" ANDREW WHALEN, Associated Press Writer,

- Haas, Jonathan; Winifred Creamer; Alvaro Ruiz (23 December 2004). "Dating the Late Archaic occupation of the Norte Chico region in Peru". Nature. 432 (7020): 1020–1023. Bibcode:2004Natur.432.1020H. doi:10.1038/nature03146. PMID 15616561.

- See a map of Norte Chico sites at https://diggingperu.wordpress.com/context/the-norte-chico.

- Mann, Charles C. (7 January 2005). "Oldest Civilization in the Americas Revealed". Science. 307 (5706): 34–35. doi:10.1126/science.307.5706.34. PMID 15637250.

- Braswell, Geoffrey (16 April 2014). The Maya and Their Central American Neighbors: Settlement Patterns, Architecture, Hieroglyphic Texts and Ceramics. Routledge. p. 408. ISBN 9781317756088.

- Haas, Jonathan; Winifred Creamer; Alvaro Ruiz (2005). "Power and the Emergence of Complex Polities in the Peruvian Preceramic". Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association. 14 (1): 37–52. doi:10.1525/ap3a.2004.14.037.

- "Oldest city in the Americas". BBC News. 26 April 2001. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- Sandweiss, Daniel H.; Michael E. Moseley (2001). "Amplifying Importance of New Research in Peru". Science. 294 (5547): 1651–1653. doi:10.1126/science.294.5547.1651d. PMID 11724063.

- Moseley, Michael. "The Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization: An Evolving Hypothesis". The Hall of Ma'at. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- Moseley, Michael (1975). The Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization. Menlo Park: Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8465-4800-3.

- Miller, Kenneth (September 2005). "Showdown at the O.K. Caral". Discover. 26 (9). Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- Belsie, Laurent (January 2002). "Civilization lost?". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- Hoag, Hanna (15 April 2003). "Oldest evidence of Andean religion found". Nature News (online). doi:10.1038/news030414-4.

- Hecht, Jeff (14 April 2003). "America's oldest religious icon revealed". New Scientist (online). Retrieved 13 February 2007.

- From summary three, Shady (1997)

- Mann, Charles C. (12 August 2005). "Unraveling Khipu's Secrets". Science. 309 (5737): 1008–1009. doi:10.1126/science.309.5737.1008. PMID 16099962.

- "Archaeologists shed new light on Americas' earliest known civilization" (Press release). Northern Illinois University. 22 December 2004. Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 1 February 2007.

- Burger (1992), Chavin and the Origins of Andean Civilization

- Nichols, Deborah L., and Christopher A. Pool. The Oxford Handbook of Mesoamerican Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2012. Print.

- Roush, Wade (9 May 1997). "Archaeobiology: Squash Seeds Yield New View of Early American Farming". Science. 276 (5314): 894–895. doi:10.1126/science.276.5314.894.

- Trigger, Bruce G., Wilcomb E. Washburn, and Richard E. W. Adams. The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas. Cambridge, England: Cambridge UP, 1996. Print.

- "Coxcatlan phase – Mexican history".

- Watson, Traci (22 January 2013). "Earliest Evidence of Chocolate in North America". Science. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Borevitz, Justin O.; Motamayor, Juan C.; Lachenaud, Philippe; da Silva e Mota, Jay Wallace; Loor, Rey; Kuhn, David N.; Brown, J. Steven; Schnell, Raymond J. (2008). "Geographic and Genetic Population Differentiation of the Amazonian Chocolate Tree (Theobroma cacao L)". PLoS ONE. 3 (10): e3311. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3311M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003311. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2551746. PMID 18827930.

- Powis, Terry G.; Hurst, W. Jeffrey; del Carmen Rodríguez, María; Ortíz C., Ponciano; Blake, Michael; Cheetham, David; Coe, Michael D.; Hodgson, John G. (2007). "Oldest chocolate in the New World". Antiquity. 81 (314).

- Diehl, Richard A. (2004). The Olmecs : America's First Civilization. London: Thames and Hudson

- Beck, Roger B.; Linda Black, Larry S. Krieger, Phillip C. Naylor, Dahia Ibo Shabaka (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 978-0-395-87274-1.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Pool, Christopher A. (2007). Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Coe, p. 44.

- Lawler, p. 23

- Pool, p. 193.

- Coe (1967), p. 72. Alternatively, the mutilation of these monuments may be unrelated to the decline and abandonment of San Lorenzo. Some researchers believe that the mutilation had ritualistic aspects, particularly since most mutilated monuments were reburied in a row.

- Pool, p. 135. Diehl, pp. 58–59, 82.

- Gonzalez Lauck 1996, p. 80

- Colman 2010

- Pohl 2005, p. 10

- Heizer 1968

- Drucker 1961, p. 1

- Nagy, Christopher (1997). "The Geoarchaeology of Settlement in the Grijalva Delta". In Barbara L. Stark; Philip J. Arnold III. Olmec to Aztec: Settlement Patterns in the Ancient Gulf Lowlands. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 253–277

- Coe, Michael D. (1968). America's First Civilization: Discovering the Olmec. New York: The Smithsonian Library.

- Coe, Michael D.; Rex Koontz (2002). Mexico: from the Olmecs to the Aztecs (5th edition, revised and enlarged ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson.

- Wilford, John Noble; “Mother Culture, or Only a Sister?”, The New York Times, 15 March 2005.

- John E. Findling; Kimberly D. Pelle (2004). Encyclopedia of the Modern Olympic Movement. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-313-32278-5.

- Wayne C. Thompson; Mark H. Mullin. Western Europe, 1983. Stryker-Post Publications. p. 337.

for ancient Greece was the cradle of Western culture ...

- Frederick Copleston (1 June 2003). History of Philosophy Volume 1: Greece and Rome. A&C Black. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8264-6895-6.

PART I PRE-SOCRATIC PHILOSOPHY CHAPTER II THE CRADLE OF WESTERN THOUGHT:

- Mario Iozzo (2001). Art and History of Greece: And Mount Athos. Casa Editrice Bonechi. p. 7. ISBN 978-88-8029-435-1.

The capital of Greece, one of the world's most glorious cities and the cradle of Western culture,

- Marxiano Melotti (25 May 2011). The Plastic Venuses: Archaeological Tourism in Post-Modern Society. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-4438-3028-7.

In short, Greece, despite having been the cradle of Western culture, was then an “other” space separate from the West.

- Library Journal. 97. Bowker. April 1972. p. 1588.

Ancient Greece: Cradle of Western Culture (Series), disc. 6 strips with 3 discs, range: 44–60 fr., 17–18 min

- Stanley Mayer Burstein (2002). Current Issues and the Study of Ancient History. Regina Books. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-930053-10-6.

and making Egypt play the same role in African education and culture that Athens and Greece do in Western culture.

- Murray Milner, Jr. (8 January 2015). Elites: A General Model. John Wiley & Sons. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-7456-8950-0.

Greece has long been considered the seedbed or cradle of Western civilization.

- Slavica viterbiensia 003: Periodico di letterature e culture slave della Facoltà di Lingue e Letterature Straniere Moderne dell'Università della Tuscia. Gangemi Editore spa. 10 November 2011. p. 148. ISBN 978-88-492-6909-3.

The Special Case of Greece The ancient Greece was a cradle of the Western culture,

- Kim Covert (1 July 2011). Ancient Greece: Birthplace of Democracy. Capstone. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4296-6831-6.

Ancient Greece is often called the cradle of western civilization. ... Ideas from literature and science also have their roots in ancient Greece.

- Henry Turner Inman. Rome: the cradle of western civilisation as illustrated by existing monuments. ISBN 9781177738538.

- Michael Ed. Grant (1964). The Birth Of Western Civilisation, Greece & Rome. Amazon.co.uk. Thames & Hudson. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- HUXLEY, George; et al. "9780500040034: The Birth of Western Civilization: Greece and Rome". AbeBooks.com. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- "Athens. Rome. Jerusalem and Vicinity. Peninsula of Mt. Sinai.: Geographicus Rare Antique Maps". Geographicus.com. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- "Download This PDF eBooks Free" (PDF). File104.filthbooks.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

Sources

- Samuel Noah Kramer (1959). Anchor Paperback. Doubleday Anchor Books.

- Samuel Noah Kramer (1969). Cradle of Civilization. Little Brown & Co. ISBN 978-0-316-32617-9.

- Georg Feuerstein (2001). In Search of the Cradle of Civilization. Quest Books. ISBN 978-0-8356-0741-4.