History of Sumer

The history of Sumer, taken to include the prehistoric Ubaid and Uruk periods, spans the 5th to 3rd millennia BCE, ending with the downfall of the Third Dynasty of Ur around 2004 BCE, followed by a transitional period of Amorite states before the rise of Babylonia in the 18th century BCE.

The first settlement in southern Mesopotamia was Eridu. The Sumerians claimed that their civilization had been brought, fully formed, to the city of Eridu by their god Enki or by his advisor (or Abgallu from ab=water, gal=big, lu=man), Adapa U-an (the Oannes of Berossus). The first people at Eridu brought with them the Samarra culture from northern Mesopotamia and are identified with the Ubaid period, but it is not known whether or not these were Sumerians (associated later with the Uruk period).

The Sumerian king list is an ancient text in the Sumerian language listing kings of Sumer, including several foreign dynasties. Some of the earlier dynasties may be mythical; the historical record does not open up before the first archaeologically attested ruler, Enmebaragesi (c. 2600 BCE), while conjectures and interpretations of archaeological evidence can vary for earlier events. The best-known dynasty, that of Lagash, is omitted from the kinglist.

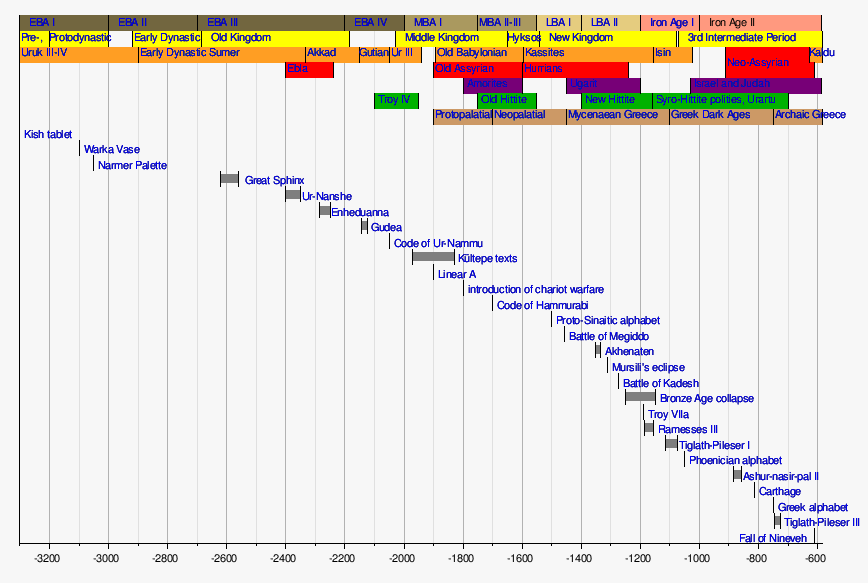

Timeline

- Dates are approximate, consult particular article for details

- Uruk III = Jemdet Nasr period[1]

Earliest city-states

.svg.png)

Permanent year-round urban settlement may have been prompted by intensive agricultural practices. The work required in maintaining irrigation canals called for, and the resulting surplus food enabled, relatively concentrated populations. The centres of Eridu and Uruk, two of the earliest cities, had successively elaborated large temple complexes built of mudbrick. Developing as small shrines with the earliest settlements, by the Early Dynastic I period, they had become the most imposing structures in their respective cities, each dedicated to its own respective god. From south to north, the principal temple-cities, their principal temple complex, and the gods they served,[2] were

- Eridu, E-Abzu, Enki

- Ur, E-kishnugal, Nanna (moon)

- Larsa, E-babbar, Utu (sun)

- Uruk, E-anna, Inana and An

- Bad-tibira, E-mush, Dumuzi and Inana

- Girsu, E-ninnu, Ningirsu

- Umma, E-mah, Shara (son of Inana)

- Nippur, E-kur, Enlil

- Shuruppak, E-dimgalanna, Sud (variant of Ninlil, wife of Enlil)

- Marad, E-igikalamma, Lugal-Marada (variant of Ninurta)

- Kish, ?, Ninhursag

- Sippar, E-babbar, Utu (sun)

- Kutha, E-meslam, Nergal

Before 3000 BCE the political life of the city was headed by a priest-king (ensi) assisted by a council of elders[3] and based on these temples, but it is unknown how the cities had secular rulers rise in prominence from the earliest times.[4] The development and system of administration led to the development of archaic tablets[5] around 3500 BCE[6]-3200 BCE[7] and ideographic writing (c. 3100 BCE) was developed into logographic writing around 2500 BCE (and a mixed form by about 2350 BCE).[8] As Sumerologist Christopher Woods[9] points out in Earliest Mesopotamian Writing: "A precise date for the earliest cuneiform texts has proved elusive, as virtually all the tablets were discovered in secondary archaeological contexts, specifically, in rubbish heaps that defy accurate stratigraphic analysis. The sun-hardened clay tablets, having obviously outlived their usefulness, were used along with other waste, such as potsherds, clay sealings, and broken mudbricks, as fill in leveling the foundations of new construction — consequently, it is impossible to establish when the tablets were written and used."[10] Even so, it is proposed that the ideas of writing developed across the area, according to Theo J. H. Krispijn,[11][12] along the following time-frame:[13]

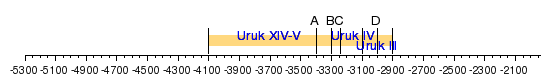

Relative stratigraphy chronology

- A : c. 3400 BCE : Numerical Tablet; B : c. 3300 BCE : Numerical Tablet with Logograms;

C : c. 3240 BCE : Script (Phonograms); D : c. 3000 BCE : Lexical Script

- A : c. 3400 BCE : Numerical Tablet; B : c. 3300 BCE : Numerical Tablet with Logograms;

History

Pre-Flood

Sumerian King List

None of the following pre-dynastic antediluvian rulers have been verified as historical via archaeological excavations, epigraphical inscriptions, or otherwise. While there is no evidence they ever reigned as such, the Sumerians purported them to have lived in the mythical era before the "Flood". The antediluvian reigns were measured in Sumerian numerical units known as "sars" (units of 3600), "ners" (units of 600), and "sosses" (units of 60.) Early dates are approximate, and are based on available archaeological data; for most pre-Sargonic rulers listed, the "Sumerian King List" (SKL) is itself the lone source of information. The SKL is an ancient manuscript originally recorded in the Sumerian language, listing kings of Sumer from both Sumerian and neighboring dynasties, their supposed reign lengths, and the locations of kingship. Throughout its Bronze Age existence, the document evolved into a political tool. Its final and single attested version, dating to the Middle Bronze Age, aimed to legitimize Isin's claims to hegemony when Isin was vying for dominance with Larsa and other neighboring city-states in Lower Mesopotamia.[14][15]

The SKL blends prehistorical, presumably mythical pre-dynastic rulers enjoying implausibly lengthy reigns with later, more plausibly historical dynasties. Although the primal kings are historically unattested, this does not preclude their possible correspondence with historical rulers who were later mythicized. Some Assyriologists view the predynastic kings as a later fictional addition.[14][16] Only one ruler listed is known to be female: Kug-Bau, “the (female) tavern-keeper,” who alone accounts for the Third Dynasty of Kish. The earliest listed ruler whose historicity has been archaeologically verified is Enmebaragesi of Kish, c. 2600 BCE.

Reference to both Enmebaragesi of Kish and his successor (Aga of Kish) in the Epic of Gilgamesh has led to speculation that Gilgamesh himself may have been a historical king of Uruk. Three dynasties are absent from the list: the Larsa dynasty, which vied for power with the (included) Isin dynasty during the Isin-Larsa period; and the two dynasties of Lagash, which respectively preceded and ensued the Akkadian Empire, when Lagash exercised considerable influence in the region. Lagash in particular is known directly from archaeological artifacts dating from c. 2500 BCE. The SKL is important to the Bronze Age chronology of the ancient near east. However, the fact that many of the dynasties listed reigned simultaneously from varying localities makes it difficult to reproduce a strict linear chronology.[14]

Antediluvian rulers

The mythological antediluvian section of the SKL has the following entry: "After the kingship descended from Heaven, the kingship was in Eridu. In Eridu, Alulim became king; he ruled for 28,800 years."[17][18] William H. Shea suggests that Alulim was a contemporary of the Biblical figure Adam (whose name and character may have been derived from "Adapa" of ancient Mesopotamian religion.[19] In a chart of antediluvian generations in both Babylonian and Biblical traditions, professor William Wolfgang Hallo associated Alulim with Adapa. The earliest known use of the name "Adam" as a genuine name in historicity is "Adamu".[20] The "Assyrian King List" stated that Tudiya (the earliest named Assyrian king) was succeeded by Adamu.[21] The Assyriologist Georges Roux stated that Tudiya would have lived c. 2450 BCE — c. 2400 BCE. The SKL has the following entries for Alulim's successors: "Alalngar ruled for 36,000 years. 2 kings; they ruled for 64,800 years. Then Eridu fell and the kingship was taken to Bad-tibira. In Bad-tibira, En-men-lu-ana ruled for 43,200 years. En-men-gal-ana ruled for 28,800 years." Dumuzid, the Shepherd is the subject of a series of epic poems in Sumerian literature and the SKL has the following entry for him: "Dumuzid, the shepherd, ruled for 36,000 years." However, in these tablets he is associated not with Bad-tibira but with Uruk, where a namesake ("Dumuzid, the Fisherman") was king sometime after the Flood (in between Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh). Following Dumuzid (the Shepherd), the SKL has these entries: "3 kings; they ruled for 108,000 years. Then Bad-tibira fell and the kingship was taken to Larak. In Larak, En-sipad-zid-ana ruled for 28,800 years. 1 king; he ruled for 28,800 years. Then Larak fell and the kingship was taken to Sippar. In Sippar, En-men-dur-ana became king; he ruled for 21,000 years. 1 king; he ruled for 21,000 years. Then Sippar fell and the kingship was taken to Shuruppak. In Shuruppak, Ubara-Tutu became king; he ruled for 18,600 years. 1 king; he ruled for 18,600 years. In 5 cities 8 kings; they ruled for 241,200 years." The name of En-men-dur-ana means "chief of the powers of Dur-an-ki", while Dur-an-ki, in turn, means: "the meeting-place of heaven and earth" (literally: "bond of above and below").[22] A myth written in a Semitic language tells of En-men-dur-ana being taken to heaven by the gods Shamash and Adad, and taught the secrets of heaven and of earth.

The mythological pre-dynastic period of the Sumerian king list portrays the passage of power in antediluvian times from Eridu to Shuruppak in the south, until a major deluge occurred. Some time after that, the hegemony reappears in the northern city of Kish at the start of the Early Dynastic period. Archaeologists have confirmed the presence of a widespread layer of riverine silt deposits shortly after the Piora oscillation that interrupted the sequence of settlement. It left a few feet of yellow sediment in the cities of Shuruppak and Uruk and extended as far north as Kish. The polychrome pottery characteristic of the Jemdet Nasr period (3100–2900 BC) below the sediment layer was followed by Early Dynastic I artifacts above the sediment layer. The earliest tablets from this period were retrieved from Jemdet Nasr in 1928. They depict complex arithmetic calculations such as the areas of field-plots. However, they have never been fully deciphered, and it is not even certain that the few words on them represent the Sumerian language.

Early Dynastic period

.jpg)

The Early Dynastic Period began after a cultural break with the preceding Jemdet Nasr period that has been radio-carbon dated to about 2900 BC at the beginning of the Early Dynastic I Period. No inscriptions have yet been found verifying any names of kings that can be associated with the Early Dynastic I period. The ED I period is distinguished from the ED II period by the narrow cylinder seals of the ED I period and the broader wider ED II seals engraved with banquet scenes or animal-contest scenes.[23] The Early Dynastic II period is when Gilgamesh, the famous king of Uruk, is believed to have reigned.[24] Texts from the ED II period are not yet understood. Later inscriptions have been found bearing some Early Dynastic II names from the King List. The Early Dynastic IIIa period, also known as the Fara period (named for the site of the city of Shuruppak),[25] is when syllabic writing began. Accounting records and an undeciphered logographic script existed before the Fara Period, but the full flow of human speech was first recorded around 2600 BC at the beginning of the Fara Period.[26] The Early Dynastic IIIb period is also known as the Pre-Sargonic period.

Hegemony, which came to be conferred by the Nippur priesthood, alternated among a number of competing dynasties, hailing from Sumerian city-states traditionally including Kish, Uruk, Ur, Adab and Akshak, as well as some from outside of southern Mesopotamia, such as Awan, Hamazi, and Mari, until the Akkadians, under Sargon of Akkad, overtook the area.

First Dynasty of Kish

After a flood occurred in Sumer, kingship is said to have resumed at Kish. The earliest Dynastic name on the list known from other legendary sources is Etana, whom it calls "the shepherd, who ascended to heaven and consolidated all the foreign countries". He was estimated by Roux[27] to have lived approximately 3000 BC. Among the 11 kings who followed, a number of Semitic Akkadian names are recorded, suggesting that these people made up a sizable proportion of the population of this northern city. The earliest monarch on the list whose historical existence has been independently attested through archaeological inscription is En-me-barage-si of Kish (c. 2600 BC), said to have defeated Elam and built the temple of Enlil in Nippur. Enmebaragesi's successor, Aga, is said to have fought with Gilgamesh of Uruk, the fifth king of that city. From this time, for a period Uruk seems to have had some kind of hegemony in Sumer. This illustrates a weakness of the Sumerian kinglist, as contemporaries are often placed in successive dynasties, making reconstruction difficult.

First Dynasty of Uruk

Mesh-ki-ang-gasher is listed as the first King of Uruk. He was followed by Enmerkar.[30] The epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta[31] tells of his voyage by river to Aratta, a mountainous, mineral-rich country up-river from Sumer. He was followed by Lugalbanda, also known from fragmentary legends, and then by Dumuzid, the Fisherman. The most famous monarch of this dynasty was Dumuzid's successor Gilgamesh, hero of the Epic of Gilgamesh, where he is called Lugalbanda's son. Ancient, fragmentary copies of this text have been discovered in locations as far apart as Hattusas in Anatolia, Megiddo in Israel, and Tell el Amarna in Egypt.

First Dynasty of Ur

This dynasty is dated to the 26th century BC.[32] Meskalamdug is the first archaeologically recorded king (Lugal from lu=man, gal=big) of the city of Ur. He was succeeded by his son Akalamdug, and Akalamdug by his son Mesh-Ane-pada. Mesh-Ane-pada is the first king of Ur listed on the king list, and it says he defeated Lugalkildu of Uruk. He also seems to have subjected Kish, thereafter assuming the title "King of Kish" for himself. This title would be used by many kings of the preeminent dynasties for some time afterward. King Mesilim of Kish is known from inscriptions from Lagash and Adab stating that he built temples in those cities, where he seems to have held some influence. He is also mentioned in some of the earliest monuments from Lagash as arbitrating a border dispute between Lugal-sha-engur, ensi (high priest or governor) of Lagash, and the ensi of their main rival, the neighbouring town of Umma. Mesilim's placement before, during, or after the reign of Mesannepada in Ur is uncertain, owing to the lack of other synchronous names in the inscriptions, and his absence from the king list.

Dynasty of Awan

This dynasty is dated to the 26th century BC, about the same time as Elam is also mentioned clearly.[33] According to the Sumerian king list, Elam, Sumer's neighbor to the east, held the kingship in Sumer for a brief period, based in the city of Awan.

Second Dynasty of Uruk

Enshakushanna was a king of Uruk in the later 3rd millennium BC who is named on the Sumerian king list, which states his reign to have been 60 years. He was succeeded in Uruk by Lugal-kinishe-dudu, but the hegemony seems to have passed briefly to Eannatum of Lagash.

Empire of Lugal-Ane-mundu of Adab

Following this period, the region of Mesopotamia seems to have come under the sway of a Sumerian conqueror from Adab, Lugal-Ane-mundu, ruling over Uruk, Ur, and Lagash. According to inscriptions, he ruled from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean, and up to the Zagros Mountains, including Elam.[34] However, his empire fell apart with his death; the king-list indicates that Mari in Upper Mesopotamia was the next city to hold the hegemony.

Kug-Bau and the Third Dynasty of Kish

The Third Dynasty of Kish, represented solely by Kug-Bau or Kubaba, is unique in the fact that she was the only woman named on the king-list to reign as "king". It adds that she had been a tavern keeper before overthrowing the hegemony of Mari and becoming monarch. In later centuries she was worshipped as a minor goddess, particularly at Carchemish, achieving some status in the Hurrian and Hittites periods. In the post-Hittite Phrygian period she was called Kubele (Latin Cybele), Great Mother of the Gods.

Dynasty of Akshak

Akshak too achieved independence with a line of rulers extending from Puzur-Nirah, Ishu-Il, and Shu-Suen, son of Ishu-Il, before being defeated by the rulers in the Fourth Dynasty of Kish.

First Dynasty of Lagash

This dynasty is dated to the 25th century BC. En-hegal is recorded as the first known ruler of Lagash, being tributary to Uruk. His successor Lugal-sha-engur was similarly tributary to Mesilim. Following the hegemony of Mesannepada of Ur, Ur-Nanshe succeeded Lugal-sha-engur as the new high priest of Lagash and achieved independence, making himself king. He defeated Ur and captured the king of Umma, Pabilgaltuk. In the ruins of a building attached by him to the temple of Ningirsu, terracotta bas reliefs of the king and his sons have been found, as well as onyx plates and lions' heads in onyx reminiscent of Egyptian work.[35] One inscription states that ships of Dilmun (Bahrain) brought him wood as tribute from foreign lands. He was succeeded by his son Akurgal.

Eannatum, grandson of Ur-Nanshe, made himself master of the whole of the district of Sumer, together with the cities of Uruk (ruled by Enshakushana), Ur, Nippur, Akshak, and Larsa.[35] He also annexed the kingdom of Kish; however, it recovered its independence after his death.[35] Umma was made tributary—a certain amount of grain being levied upon each person in it, that had to be paid into the treasury of the goddess Nina and the god Ningirsu.[35] Eannatum's campaigns extended beyond the confines of Sumer, and he overran a part of Elam, took the city of Az on the Persian Gulf, and exacted tribute as far as Mari; however many of the realms he conquered were often in revolt. During his reign, temples and palaces were repaired or erected at Lagash and elsewhere; the town of Nina—that probably gave its name to the later Niniveh—was rebuilt, and canals and reservoirs were excavated. Eannatum was succeeded by his brother, En-anna-tum I. During his rule, Umma once more asserted independence under Ur-Lumma, who attacked Lagash unsuccessfully. Ur-Lumma was replaced by a priest-king, Illi, who also attacked Lagash.

His son and successor Entemena restored the prestige of Lagash.[35] Illi of Umma was subdued, with the help of his ally Lugal-kinishe-dudu or Lugal-ure of Uruk, successor to Enshakushana and also on the king-list. Lugal-kinishe-dudu seems to have been the prominent figure at the time, since he also claimed to rule Kish and Ur. A silver vase dedicated by Entemena to his god is now in the Louvre.[35] A frieze of lions devouring ibexes and deer, incised with great artistic skill, runs round the neck, while the eagle crest of Lagash adorns the globular part. The vase is a proof of the high degree of excellence to which the goldsmith's art had already attained.[35] A vase of calcite, also dedicated by Entemena, has been found at Nippur.[35] After Entemena, a series of weak, corrupt priest-kings is attested for Lagash. The last of these, Urukagina, was known for his judicial, social, and economic reforms, and his may well be the first legal code known to have existed.

Empire of Lugal-zage-si of Uruk

Urukagina (c. 2359–2335 BC short chronology) was overthrown and his city Lagash captured by Lugal-zage-si, the high priest of Umma. Lugal-zage-si also took Uruk and Ur, and made Uruk his capital. In a long inscription that he made engraved on hundreds of stone vases dedicated to Enlil of Nippur, he boasts that his kingdom extended "from the Lower Sea (Persian Gulf), along the Tigris and Euphrates, to the Upper Sea" or Mediterranean.[35] His empire was overthrown by Sargon of Akkad.

Akkadian Empire

The Akkadian period lasted c. 2334–2218 BC (short chronology). The following is a list of known kings of this period:

| Sargon | c. 2334–2279 BC | |

| Rimush | c. 2278–2270 BC | younger son of Sargon |

| Man-ishtishu | c. 2269–2255 BC | elder son of Sargon |

| Naram-Sin | c. 2254–2218 BC | son of Man-ishtishu |

| Shar-kali-sharri | c. 2217–2193 BC | son of Naram-Suen |

| Irgigi | ||

| Imi | ||

| Nanum | ||

| Elulu | ||

| Dudu | c. 2189–2168 BC | |

| Shu-Durul | c. 2168–2147 BC | Akkad defeated by the Gutians |

Gutian period

Following the fall of Sargon's Empire to the Gutians, a brief "Dark Ages" ensued. This period lasted c. 2147–2047 BC (short chronology).

Second Dynasty of Lagash

This period lasted c. 2260–2110 BC.

| Ki-Ku-Id | ||

| Engilsa | ||

| Ur-A | ||

| Lugalushumgal | ||

| Puzer-Mama | c. 2200 BC | contemporary of Shar-kali-sharri of Akkad |

| Ur-Utu | ||

| Ur-Mama | ||

| Lu-Baba | ||

| Lugula | ||

| Kaku or Kakug | ||

| Ur-Bau or Ur-baba | c. 2093–2080 BC (short) | |

| Gudea | c. 2080–2060 BC | son-in-law of Ur-baba |

| Ur-Ningirsu | c. 2060–2055 BC | son of Gudea |

| Pirigme or Ugme | c. 2055–2053 BC | |

| Ur-gar | c. 2053–2049 BC | |

| Nammahani | c. 2049–2046 BC | grandson of Kaku, defeated by Ur-Nammu |

Fifth Dynasty of Uruk

This dynasty lasted between c. 2055–2048 BC short chronology. The Gutians were ultimately driven out by the Sumerians under Utu-hegal, the only king of this dynasty, who in turn was defeated by Ur-Nammu of Ur.

Third Dynasty of Ur

The Third Dynasty of Ur is dated to c. 2047–1940 BC short chronology. Ur-Nammu of Ur defeated Utu-hegal of Uruk and founded the Third Dynasty of Ur. Although the Sumerian language ("Emegir") was again made official, Sumerian identity was already in decline, as the population became continually absorbed into the Akkadian (Assyro-Babylonian) population.[37][38]

After the Ur III dynasty was destroyed by the Elamites in 2004 BC, a fierce rivalry developed between the city-states of Larsa, more under Elamite than Sumerian influence, and Isin, that was more Amorite (as the Western Semitic nomads were called). Archaeologically, the fall of the Ur III dynasty corresponds to the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age. The Semites ended up prevailing in Mesopotamia by the time of Hammurabi of Babylon, who founded the Babylonian Empire, and the language and name of Sumer gradually passed into the realm of antiquarian scholars. Nevertheless, Sumerian influence on Babylonia, and all subsequent cultures in the region, was undeniably great.

During the third millennium BC, there developed a very intimate cultural symbiosis between the Sumerians and the Akkadians, which included widespread bilingualism.[37] The influence of Sumerian on Akkadian (and vice versa) is evident in all areas, from lexical borrowing on a massive scale, to syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence.[37] This has prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and Akkadian in the third millennium as a sprachbund.[37]

Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as the spoken language of Mesopotamia somewhere around the turn of the third and the second millennium BC (the exact dating being a matter of debate),[38] but Sumerian continued to be used as a sacred, ceremonial, literary and scientific language in Mesopotamia until the first century AD.

References

- Pollock, Susan (1999), Ancient Mesopotamia. The Eden that never was, Case Studies in Early Societies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 2, ISBN 978-0-521-57568-3

- George, Andrew (1993), House Most High. The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns)

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (Ed) (1939),"The Sumerian King List" (Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago; Assyriological Studies, No. 11.)

- Harriet Crawford. Sumer and the Sumerians. 2004. Page 28

- Cuneiform. By C. B. F. Walker.

- Records of the Past, Volume 5, Issue 11. Edited by Henry Mason Baum, Frederick Bennett Wright, George Frederick Wright. Records of the Past Exploration Society., 1906. Pg 352.

- The Adaptation of Cuneiform to Akkadian Piotr Michalowski University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

- Western Civilization: Beyond Boundaries. Cengage Learning, Jan 1, 2008. pages 12–13.

- Christopher Woods. Associate Professor of Sumerian. http://nelc.uchicago.edu/faculty/woods

- Woods, Christopher (2010), "The Earliest Mesopotamian Writing", in Woods, Christopher (ed.), Visible Language. Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond (PDF), Oriental Institute Museum Publications, 32, Chicago: University of Chicago, pp. 33–50, ISBN 978-1-885923-76-9

- The Idea of Writing: Writing Across Borders. Edited by Alex de Voogt, Joachim Friedrich Quack. BRILL, Dec 9, 2011. Page 181.

- Drs. T.J.H. (Theo) Krispijn - Assyriology - Faculty of Humanities http://www.hum.leiden.edu/lias/organisation/assyriology/krispijntjh.html

- via Dietrich Sürenhagen (1999)

- Van De Mieroop, Marc (2004). A History of the Ancient Near East. Blackwell. p. 41. ISBN 0-631-22552-8.

- The spelling of royal names follows the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature

- von Soden, Wolfram (1994). The Ancient Orient. Donald G. Schley (trans.). Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 47. ISBN 0-8028-0142-0.

- Jona Lendering (2006). "Sumerian King List".

- Wang, Haicheng (2004). Writing and the Ancient State: Early China in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 1107785871. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- William H. Shea (1977). "Adam in Ancient Mesopotamian Traditions". Archived from the original on 2011-09-04.

- Hamilton, Victor (1995). The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1 - 17. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802825216.

- Roux, Georges (1992). Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 9780140125238.

- A. R. George. Babylonian topographical texts. p. 261.

- Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, page 129

- Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, page 502

- The reason for the name is historical; the first substantial find of pre-Sargonic cuneiform material was made at Tell Fara (Shuruppak) in the excavation season of 1902 by Robert Koldewey and Friedrich Delitzsch of the German Oriental Society. These finds were instrumental in the decipherment and description of archaic cuneiform in the 1910s and 1920s. Heinrich, Ernst; Andrae, Walter, eds. (1931). Fara, Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft in Fara und Abu Hatab. Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

- Early Ancient Near Eastern Law. By Claus Wilcke. Eisenbrauns, 2003. Pg 26.

- Roux, Georges (1971) "Ancient Iraq" (Penguin, Harmondsworth)

- Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003. p. 481. ISBN 9781588390431.

- "Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin". repository.edition-topoi.org.

- Identified by David Rohl with Nimrod the Hunter, mentioned in the Bible as founding Erech

- "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. 1970. p. 228. ISBN 9780521070515.

- D. T. Potts, The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge University Press, 2015 ISBN 1107094690 p79

- Samuel Kramer, The Sumerians, 51-52.

- Sayce, Archibald Henry; King, Leonard William; Jastrow, Morris (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–112.

- "Hash-hamer Cylinder seal of Ur-Nammu". British Museum.

- Deutscher, Guy (2007). Syntactic Change in Akkadian: The Evolution of Sentential Complementation. Oxford University Press US. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-19-953222-3.

- Woods C. 2006 "Bilingualism, Scribal Learning, and the Death of Sumerian". In S. L. Sanders (ed) Margins of Writing, Origins of Culture: 91–120 Chicago