Political communication

Political communication(s) is a subfield of communication and political science that is concerned with how information spreads and influences politics and policy makers, the news media and citizens.[1] Since the advent of the World Wide Web, the amount of data to analyze has exploded, and researchers are shifting to computational methods to study the dynamics of political communication. In recent years, machine learning, natural language processing, and network analysis have become key tools in the subfield. It deals with the production, dissemination, procession and effects of information, both through mass media and interpersonally, within a political context. This includes the study of the media, the analysis of speeches by politicians and those that are trying to influence the political process, and formal and informal conversations among members of the public, among other aspects. The media acts as bridge between government and public. Political communication can be defined as the connection concerning politics and citizens and the interaction modes that connect these groups to each other. Whether the relationship is formed by the modes of persuasion, Pathos, Ethos or Logos.

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

Primary topics |

|

Academic disciplines |

|

Organs of government |

| Politics Portal |

Defining the concept

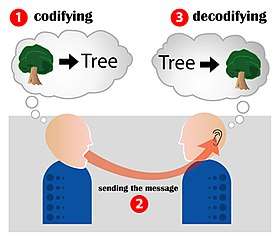

The study and practice of communication focuses on the ways and means of expression of a political nature. Robert E. Denton and Gary C. Woodward, two important contributors to the field, in Political Communication in America characterize it as the ways and intentions of message senders to influence the political environment. This includes public discussion (e.g. political speeches, news media coverage, and ordinary citizens' talk) that considers who has authority to sanction, the allocation of public resources, who has authority to make decision, as well as social meaning like what makes someone American. In their words "the crucial factor that makes communication 'political' is not the source of a message, but its content and purpose." [2] David L. Swanson and Dan Nimmo, also key members of this sub-discipline, define political communication as "the strategic use of communication to influence public knowledge, beliefs, and action on political matters." [3] They emphasize the strategic nature of political communication, highlighting the role of persuasion in political discourse. Brian McNair provides a similar definition when he writes that political communication is "purposeful communication about politics." For McNair this means that this not only covers verbal or written statements, but also visual representations such as dress, make-up, hairstyle or logo design. With other words, it also includes all those aspects that develop a "political identity" or "image".[4] Reflecting on the relationship between political communication and contemporary agenda-building, Vian Bakir defines Strategic Political Communication (SPC) as comprising 'political communication that is manipulative in intent, that utilises social scientific techniques and heuristic devices to understand human motivation, human behavior and the media environment, to inform effectively what should be communicated – encompassing its detail and overall direction – and what should be withheld, with the aim of taking into account and influencing public opinion, and creating strategic alliances and an enabling environment for government policies – both at home and abroad'.[5]

There are many academic departments and schools around the world that specialize in political communication. These programs are housed in programs of communication, journalism and political science, among others. The study of political communication is clearly interdisciplinary.

Contemporary examples of strategic political communication

The Bush Administration’s torture-for-intelligence policy, initiated soon after 9/11, was kept secret for several years, as remains the level of complicity of many other nation-states' governments. While this secret policy was gradually revealed from 2004 onwards, initiated by the Abu Ghraib torture photos, the Bush administration engaged in SPC to publicly reframe and protect its secret policy. SPC included silencing and persuasive discursive activity.[6]

- Discursive activity aimed at generating silences comprised plea bargains that silenced detainees, censoring Guantánamo detainees’ descriptions of their own torture in pre–trial hearings, deals with journalists to censor or withhold information that affected national security, weeding out personal sousveillance of torture online, suppression of visual sousveillance of torture while courts–martial and criminal investigations proceeded; destruction of videotapes of CIA interrogations; and withholding key information from intelligence oversight committees. These position those in the know as part of an elite force policing the public sphere to keep the wider public and their representatives ignorant of unpalatable but necessary official practices, relegating the likely emotional and/or moral public dissent towards such practices as unaffordable niceties.

- Persuasive discursive activity included the propagation and repetition of a few key messages consistently over time, with the aim of misdirecting public attention from the silence–generating activities. Key Bush Administration messages were that detainees were evil, dangerous terrorists; that the practice of extraordinary rendition was normal and pragmatic; that interrogation techniques, although harsh, were legal (apart from isolated acts of abuse), necessary and successful in preventing future acts of terror; and that Guantánamo was a model prison. Key British Administration messages were of initial ministerial ignorance (until 2004) of American intelligence agencies’ new interrogation strategies, after which intelligence agencies’ guidelines were tightened; and of no direct involvement of British intelligence agencies in extraordinary rendition. Key messages common to both British and American Administrations were that the Abu Ghraib sousveillance and similar visual evidence involving British soldiers were examples of isolated abuse rather than a torture policy from which lessons had been learned regarding Army training and interrogation guidance (new Army guidelines on interrogation were produced under the Bush and Blair Administrations). These key messages were propagated through a range of discursive activity (including press conferences and media interviews, authorised leaks, real–time reporting, official investigations and public inquiries) and were periodically bolstered by selective public release of once–secret documents. The consistency of key messages over time, together with the offering up of specific evidence, gives the appearance of official disclosure and truth–telling, positioning the public as a force to which political administrations willingly hold themselves accountable. However, the strategic generation of key messages and selectivity of supporting information presented across all these discursive modes means that full accountability is avoided, while the public is potentially fooled into thinking that justice has been served, all–the–while being constant targets of manipulation.

Fields and areas of study

The field of political communication is focused on 4 main areas:

- Election campaigns - Political communications involved in campaigning for elections.

- Government operations - This role is usually fulfilled by a Ministry of Communications, Information Technology or similar political entity. Such an entity is in charge of maintaining communication legislation and would be responsible for setting telecommunications policy and regulations as well as issuing broadcasting licenses, comments press releases, etc...

- Media content - The interaction between politics, media content and the public.

- Communication processes - How people communicate about politics.

According to James Chesebro, there are five critical approaches to contemporary Political communications:

- Machiavellian - i.e. power relationships

- Iconic - symbols are important

- Ritualistic - Redundant and superficial nature of political acts - manipulation of symbols.

- Confirmation - political aspects looked at as people we endorse

- Dramatistic - politics is symbolically constructed. (Kenneth Burke)

Role of social media

Social media has dramatically changed the way in which modern political campaigns are run.[7] With more digital native citizens coming into the voting population, social media have become important platforms on which politicians establish themselves and engage with the voters. [8]In the digital age, evidence across the world has showcased the increasing importance of social media in electoral politics.[9]

Taking Australia as an example below: 86% of Australians access the Internet, and with a 17,048,864 voting age population,[10] around 14,662,023 voting population has access to Internet, and 65% of them use social media, which means 9,530,314 Australian voters use social media. (The 2013 Yellow™ Social Media Report found that among internet users 65% of Australians use social media, up from 62% last year).[11]

With almost half of Australian voting population active on social media, political parties are adapting quickly to influence and connect with their voters.[12] Studies have found that journalists in Australia widely use social media in a professional context and that it has become a viable method of communication between the mainstream media and wider audiences. [13]

Social media experience relies heavily on the user themselves due to the platforms' algorithms which tailor consumer experience for each user. This results in each person seeing more like-minded news due to the increase in digital social behavior. Additionally, social media has changed politics because it has given politicians a direct medium to give their constituents information and the people to speak directly to the politicians. This informal nature can lead to informational mistakes because it is not being subjected to the same "fact-checking processes as institutional journalism." [14]

Social media creates greater opportunity for political persuasion due to the high number of citizens that regularly engage and build followings on social media. The more that a person engages on social media, the more influential they believe themselves to be, resulting in more people considering themselves to be politically persuasive.[15]

See also

- Propaganda

- Politainment

- Intelligence cycle

- List of basic political science topics

- Government operations

- Official statistics

- Political campaign

- Political Communication (journal)

- Rhetorics

- Technological nationalism

- Torture

- Sousveillance

- Social media

References

- https://www.hks.harvard.edu/fs/pnorris/Acrobat/Political%20Communications%20encyclopedia2.pdf

- Denton R.E., Woodward G.C. (1998). Political Communication in America. New York: Praeger. p. 11. ISBN 978-0275957834.

- Swanson, D. & Nimmo D. "New Directions in Political Communication: A Resource Book." Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1990, p. 9.

- McNair B. An Introduction to Political Communication, London: Routledge, 2003, p.24

- Bakir, V. (2013). Torture, Intelligence and Sousveillance in the War on Terror: Agenda–Building Struggles. Farnham: Ashgate. p. 3. ISBN 9781472402554.

- Bakir, V. Torture, Intelligence and Sousveillance in the War on Terror: Agenda–Building Struggles. Farnham: Ashgate (2013)

- Enli, Gunn (2017). "Twitter as arena for the authentic outsider: exploring the social media campaigns of Trump and Clinton in the 2016 US presidential election". European Journal of Communication. 32 (1): 50–61. doi:10.1177/0267323116682802. hdl:10852/55266.

- Kreiss, Daniel (2016). "Seizing the moment: The presidential campaigns' use of Twitter during the 2012 electoral cycle". New Media & Society. 18 (8): 1473–1490. doi:10.1177/1461444814562445.

- Wei, Ran; Xu, Larry Zhiming (2019). "New Media and Politics: A Synopsis of Theories, Issues, and Research". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.104. ISBN 9780190228613.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-06. Retrieved 2016-06-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Political Campaign and Social Media". Political Marketing. Archived from the original on 2014-01-16. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- http://www.thesocialsavior.com/benefits-of-social-media-for-business/

- Cision (2012). Journalists Views and Usage of Social Media. http://mb.cision.com/Public/329/9316712/8978ed4b0993062c.pdf

- Graber, Doris A.; Dunaway, Johanna (2017-07-20). Mass Media and American Politics. CQ Press. ISBN 9781506340227.

- Weeks, Brian E.; Ardèvol-Abreu, Alberto; Gil de Zúñiga, Homero (2015-12-31). "Online Influence? Social Media Use, Opinion Leadership, and Political Persuasion". International Journal of Public Opinion Research. 29 (2): edv050. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edv050. ISSN 0954-2892.

External links

- Political Communication section at the American Political Science Association (APSA)

- Political Communication section of the International Communication Association (ICA)

- Political Communication Division of the National Communication Association (NCA)

- Centre for European Political Communications

- The Political Communication Lab - Stanford University

- Working Papers on Political Communications - Kennedy School of Government

- Political Communications Web Archive Project

- A list of Political communications books

- Digital Crusades: observing the political communications of populist-nativist parties SVP, PVV & the FN