Christianity in Africa

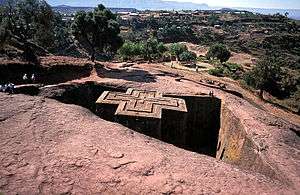

Christianity in Africa began in Egypt in the middle of the 1st century. By the end of the 2nd century it had reached the region around Carthage. Important Africans who influenced the early development of Christianity include Tertullian, Perpetua, Felicity, Clement of Alexandria, Origen of Alexandria, Cyprian, Athanasius and Augustine of Hippo. In the 4th century the Aksumite empire was Christianized, and the Nubian kingdoms of Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia followed two centuries later.

Since the spread of Islam into North Africa, the size of Christian congregations as well as their number was reduced, so that of the original churches only the Eastern Orthodox Church of Alexandria and Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria (which separated from each other during the Chalcedonian Schism) in Egypt and the Orthodox Tewahedo Church (that split into Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church) in the Horn of Africa remained. The Ethiopian church held its own distinct religious customs and a unique canon of the Bible. The Ethiopian church community in the Horn of Africa wasn't the product of European missionary work, rather, it had spread through missionaries much earlier (while the P'ent'ay churches are works of a Protestant reformation within Ethiopian Christianity).[1] The position of the head of the Catholic Church of Africa (Archdiocese of Carthage), the only one permitted to preach in the continent, in 1246 belonged to the bishop of Morocco.[2] The bishopric of Marrakesh continued to exist until the late 16th century.[3]

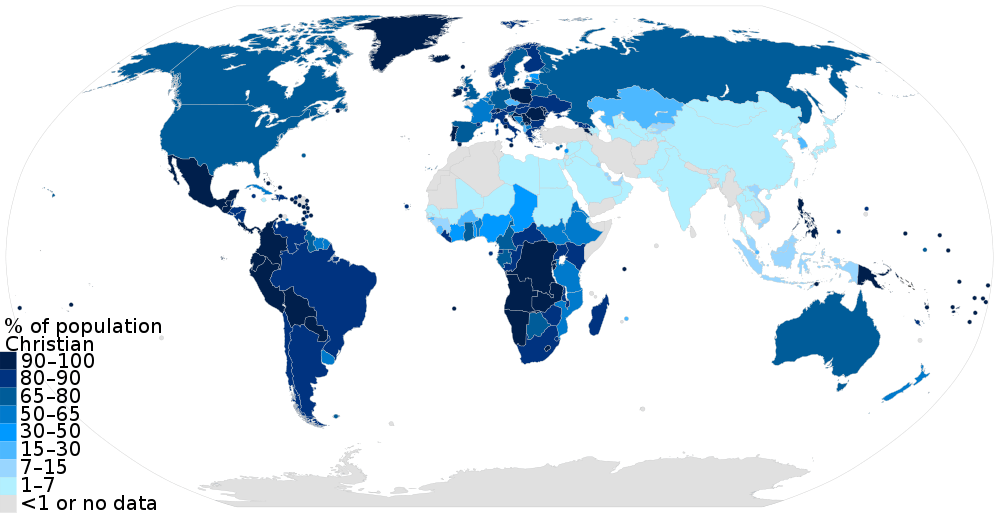

Christianity is embraced by the majority of the population in most Southern African, Southeast African, and Central African states and others in some parts of Horn of Africa and West Africa. The Coptic Christians make up a significant minority in Egypt. The World Book Encyclopedia has estimated that in 2002, Christians formed 40% of the continent's population, with Muslims forming 45%. In a relatively short time, Africa has gone from having a majority of followers of indigenous, traditional religions, to being predominantly a continent of Christians and Muslims. Since 2013, traditional African religions are declared as the majority religion only in Togo. Importantly, today within most self-declared Christian communities in Africa, there is significant and sustained syncretism with African Traditional Religious beliefs and practices.[4]

New data from the Gordon Theological Seminary shows that, for the first time ever, more number of Christians live in Africa than on any other single continent.[5]

"The results show Africa on top with 631 million Christian residents, Latin America in 2nd place with 601 million Christians, and Europe in 3rd place with 571 million Christians."[6]

History

| Christianity by country |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Oceania

|

|

South America

|

|

|

Mark the Evangelist became the first bishop of the Orthodox Church of Alexandria in about the year 43.[7] At first the church in Alexandria was mainly Greek-speaking. By the end of the 2nd century the scriptures and liturgy had been translated into three local languages. Christianity in Sudan also spread in the early 1st century, and the Nubian churches, which were established in the sixth century within the kingdoms of Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia were linked to those of Egypt.[8]

Christianity also grew in northwestern Africa (today known as the Maghreb). The churches there were linked to the Church of Rome and provided Pope Gelasius I, Pope Miltiades and Pope Victor I, all of them Christian Berbers like Saint Augustine and his mother Saint Monica.

.png)

At the beginning of the 3rd century the church in Alexandria expanded rapidly, with five new suffragan bishoprics. At this time, the Bishop of Alexandria began to be called Pope, as the senior bishop in Egypt. In the middle of the 3rd century the church in Egypt suffered severely in the persecution under the Emperor Decius. Many Christians fled from the towns into the desert. When the persecution died down, however, some remained in the desert as hermits to pray. This was the beginning of Christian monasticism, which over the following years spread from Africa to other parts of the Gohar, and Europe through France and Ireland.

The early 4th century in Egypt began with renewed persecution under the Emperor Diocletian. In the Ethiopian/Eritrean Kingdom of Aksum, King Ezana declared Christianity the official religion after having been converted by Frumentius, resulting in the promotion of Christianity in Ethiopia (eventually leading to the foundation of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church).

In these first few centuries, African Christian leaders such as Origen, Lactantius, Augustine, Tertullian, Marius Victorinus, Pachomius, Didymus the Blind, Ticonius, Cyprian, Athanasius and Cyril (along with rivals Valentinus, Plotinus, Arius and Donatus Magnus) influenced the Christian world outside Africa with responses to Gnosticism, Arianism, Montanism, Marcionism, Pelagianism and Manichaeism, and the idea of the University (after the Library of Alexandria), understanding of the Trinity, Vetus Latina translations, methods of exegesis and biblical interpretation, ecumenical councils, monasticism, Neoplatonism and African literary, dialectical and rhetorical traditions.[9]

After the Muslim conquest of Eastern Roman North Africa

.png)

Archaeological and scholarly research has shown that Christianity existed after the Muslim conquests. The Catholic church gradually declined along with local Latin dialect.[10][11]

Many causes have been seen as to leading to the decline of Christianity in the Maghreb. One of them is the constant wars and conquests as well as persecutions. In addition many Christians also migrated to Europe. The Church at that time lacked the backbone of a monastic tradition and was still suffering from the aftermath of heresies including the so-called Donatist heresy, and that this contributed to the early obliteration of the Church in the present day Maghreb. Some historians contrast this with the strong monastic tradition in Coptic Egypt, which is credited as a factor that allowed the Coptic Church to remain the majority faith in that country until around after the 14th century despite numerous persecutions. In addition, the Romans and the Byzantines were unable to completely assimilate the indigenous people like the Berbers.[12][13]

Another view however that exists is that Christianity in North Africa ended soon after conquest of North Africa by the Islamic Umayyad Caliphate between AD 647–709 effectively.[14]

.jpg)

However, new scholarship has appeared that disputes this. There are reports that the Roman Catholic faith persisted in the region from Tripolitania (present-day western Libya) to present-day Morocco for several centuries after the completion of the Arab conquest by 700.[15] A Christian community is recorded in 1114 in Qal'a in central Algeria. There is also evidence of religious pilgrimages after 850 to tombs of Catholic saints outside the city of Carthage, and evidence of religious contacts with Christians of Muslim Spain. In addition, calendar reforms adopted in Europe at this time were disseminated amongst the indigenous Christians of Tunis, which would have not been possible had there been an absence of contact with Rome.

Local Catholicism came under pressure when the Muslim regimes of the Almohads and Almoravids came into power, and the record shows demands made that the local Christians of Tunis convert to Islam. There are reports of Christian inhabitants and a bishop in the city of Kairouan around 1150 AD - a significant event, since this city was founded by Arab Muslims around 680 AD as their administrative center after their conquest. A letter in Catholic Church archives from the 14th century shows that there were still four bishoprics left in North Africa, admittedly a sharp decline from the over four hundred bishoprics in existence at the time of the Arab conquest.[16] The Almohad Abd al-Mu'min forced the Christians and Jews of Tunis to convert in 1159. Ibn Khaldun hinted at a native Christian community in 14th century in the villages of Nefzaoua, south-west of Tozeur. These paid the jizuah and had some people of Frankish descent among them.[17] Berber Christians continued to live in Tunis and Nefzaoua in the south of Tunisia up until the early 15th century, and in the first quarter of the 15th century we even read that the native Christians of Tunis, though much assimilated, extended their church, perhaps because the last Christians from all over the Maghreb had gathered there. However, they were not in communion with the Catholic church.[16] The community of Tunisian Christians existed in the town of Tozeur up to the 18th century.[18]

Another group of Christians who came to North Africa after being deported from Islamic Spain were called the Mozarabic. They were recognised as forming the Moroccan Church by Pope Innocent IV.[19]

In June 1225, Honorius III issued the bull Vineae Domini custodes that permitted two friars of the Dominican Order named Dominic and Martin to establish a mission in Morocco and look after the affairs of Christians there.[20] The bishop of Morocco Lope Fernandez de Ain was made the head of the Church of Africa, the only church officially allowed to preach in the continent, on 19 December 1246 by Innocent IV.[2]

The medieval Moroccan historian Ibn Abi Zar stated that the Almohad caliph Abu al-Ala Idris al-Ma'mun had built a church in Marrakech for the Christians to freely practice their faith at Fernando III's insistence. IV asked emirs of Tunis, Ceuta and Bugia to permit Lope and Franciscian friars to look after the Christians in those regions. He thanked the Caliph al-Sa'id for granting protection to the Christians and requested to allow them to create fortresses along the shores, but the Caliph rejected this request.[21]

Another phase of Christianity in Africa began with the arrival of Portuguese in the 15th century.[22] After the end of Reconquista, the Christian Portuguese and Spanish captured many ports in North Africa.[23]

The bishopric of Marrakesh continued to exist until the late 16th century and was borne by the suffragans of Seville. Juan de Prado who had attempted to re-establish the mission was killed in 1631. A Franciscan monastery built in 1637 was destroyed in 1659 after the downfall of the Saadi dynasty. A small Franciscan chapel and monastery in the mellah of the city existed until the 18th century.[3]

The growth of Catholicism in the region after the French conquest was built on European colonizers and settlers, and these immigrants and their descendants mostly left when the countries of the region became independent. As of the last census in Algeria, taken on 1 June 1960, there were 1,050,000 non-Muslim civilians (mostly Catholic) in Algeria (10 percent of the total population including 140,000 Algerian Jews).[24]

In 2009, the UNO counted 45,000 Roman Catholics and 50,000 to 100,000 Protestants in Algeria. Conversions to Christianity have been most common in Kabylie, especially in the wilaya of Tizi Ouzou.[25] In that wilaya, the proportion of Christians has been estimated to be between 1% and 5%. A 2015 study estimates 380,000 Muslims converted to Christianity in Algeria.[26]

In Morocco the expatriate Christian community (Roman Catholic and Protestant) consists of 5,000 practicing members, although estimates of Christians residing in the country at any particular time range up to 25,000. Most Christians reside in the Casablanca, Tangier and Rabat urban areas.[27] The majority of Christians in Morocco are foreigners, although Voice of the Martyrs reports there is a growing number of native Moroccans (45,000) converting to Christianity, especially in the rural areas. Many of the converts are baptized secretly in Morocco's churches.[28]

The Christian community in Tunisia, composed of indigenous residents, Tunisians of Italian and French descent, and a large group of native-born citizens of Berber and Arab descent, numbers 50,000 and is dispersed throughout the country.The Office for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor in the United States also noted the presence of thousands of Tunisians who converted to Christianity .[29]

Africanizing Christianity

Within different geographical areas, Africans searched for aspects of Christianity that could more closely resemble their religious and personal practices. Adaptations of Protestantism, such as the Kimbanguist church emerged. Within the Kimbanguist church, Simon Kimbangu questioned the order of religious deliverance- would God send a white man to preach? The Kimbanguist church believed Jesus was black and regarded symbols with different weight than the Catholic and Protestant Europeans. The common practice of placing crosses and crucifixes in churches was viewed as a graven image in their eyes or a form of idolatry. Also, according to Mazrui, Kimbanguists respected the roles of women in church more than orthodox churches; they gave women the roles of priests and preachers.[30][31] Members within these churches looked for practices in the Bible that were not overtly condemned, such as polygamy. They also incorporated in their own practices relationships with objects and actions like dancing and chanting. [32] When Africans were able to read in the vernacular, they were able to interpret the Bible in their own light. Polygamy was a topic of debate- many literate Africans interpreted it as acceptable because of information contained in the Old Testament- while it was condemned by European Christianity. Dona Beatriz was a woman from Central Africa known for her controversial views on the acceptance of polygamy- she argued that Jesus never condemned it- and she was burnt at the stake. European missionaries were faced with what they considered an issue in maintaining Victorian values, while still promoting the vernacular and literacy. Missionaries largely condemned the controversial African views and worked against leaders branching out. Simon Kimbangu became a martyr, put in a cage because of Western missionaries concern, and died there.

Within African communities, there were clashes brought on by Christianization. Young leaders formed ideas based on Christianity and challenged elders. Dona Beatriz, an African prophet, made Christianity political and eventually went on to become an African Nationalist, planning to overthrow the Ugandan state with the help of other prophets. According to Paul Kollman, teaching from missionaries was up to the interpretation of each person and took different forms when acted upon. [33]

David Adamo, a Nigerian within the Aladura church chose portions of the Bible that closely resembled what his church found important. They read portions of Psalms because of the idea that missionaries were not sharing the power of their faith. They found power in reading these verses and put them into the context of their lives.

In addition to Africanizing Christianity, there were movements to Africanize Islam. In Nigeria, movements were created to arouse Muslims to de-Arabize Islam. There were clashes between people who accepted the de-Arabization and those who did not. These movements took place around 1980, resulting in violent behavior and clashes with police. Mirza Ghulam Ahmed, the founder of the Ahmadiyya sect, believed that the prophet Muhammed was the most important prophet, but not the last- departing from typical Muslim views. Sunni Africans were largely against the Ahmadiyyas; the Ahmadiyyas were the first to translate the Quran into Swahili, and the Sunnis opposed that as well. There was a militarism developed in different groups and movements like the Ahmadiyyas and the Mahdist movement and clashes between groups with opposing views.

The influenza pandemic of 1918 accelerated the Africanization of Christianity and hence its growth in twentieth century Africa[34]. As many as five million Africans are estimated to have died. European governments, churches and medicine were powerless against the plague, boosting anti-imperial sentiment and discrediting white supremacy. This contributed to growth of independent and prophetic Christian mass movements with prophecy, healings, and nationalist church restructuring. For example, the inception of the Aladura movement in Nigeria coincided with the pandemic. Evolving into the Christ Apostolic Church, it gave rise to many offshoots, which continued to emerge into the 1950s spreading with migrants around the world. For example, the Redeemed Christian Church of God, founded in 1952, has congregations in a dozen African states, Western Europe and North America.

Jesuit missions in Africa

Missionary expeditions undertaken by the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) began as early as 1548 in various regions of Africa. In 1561, Gonçalo da Silveira, a Portuguese missionary, managed to baptize Monomotapa, king of the Shona people in the territory of Zimbabwe.[35] A modest sized group of Jesuits began to establish their presence in the area of Abyssinia, or Ethiopia Superior, around the same time of Silveira's presence in Southern Africa. Although Jesuits regularly confronted persecution and harassment, their mission withstood the test of time for nearly a century. Despite this confrontation, they found success in instituting Catholic doctrine in a region that, prior to the existence of their vocation, maintained strictly established orthodoxies. During the sixteenth century, Jesuits extended their occupation into the old Kongo Kingdom, developing upon a preexisting Catholic mission which had culminated in the construction of a local church. Jesuit missions functioned similarly in Mozambique and Angola until in 1759 the Society was overcome by Portuguese authority.

The Jesuits went largely unchallenged by rival denominational missions in Africa. Other religious congregations did exist who sought to evangelize regions of the continent under Portuguese dominion, however, their influence was far less significant than that of the Christians. The Jesuit's ascendency to prominence began with the padroado in the fifteenth century and continued until other European countries initiated missions of their own, threatening Portugal's status as sole patron of the continent. The favor of the Jesuits took a negative turn in the mid eighteenth century when Portugal no longer held the same dominion in Africa as it had in the fifteenth century. The Jesuits found themselves expelled from Mozambique and Angola, as a result, the existence of Catholic missions diminished significantly in these regions.

Christian education in Africa

Christians and Muslims built schools throughout the continent of Africa, teaching missionary beliefs and philosophies. Since the Quran must only be recited in Arabic, It is necessary that a practitioner of the Muslim faith reads and understands the meaning of Arabic words in order to recite and/or memorize the Quran. As a result of the nature of Islam in Africa, Muslim missionaries were not prompted to translate their sacred text into the native language. Unlike that of Islam, Christian missionaries were compelled to spread an understanding of their gospel in the native language of the indigenous people they sought to convert. The bible was then translated and communicated in these native languages. Christian schools did teach English, as well as mathematics, philosophy, and values inherent to Western culture and civilization. The conflicting branches of secularism and religiosity within the Christian schools represents a divergence between the various goals of educational institutions within Africa.[36]

Current status

Christianity is now one of the two most widely practiced religions in Africa. There has been tremendous growth in the number of Christians in Africa - coupled by a relative decline in adherence to traditional African religions. Only nine million Christians were in Africa in 1900, but by the year 2000, there were an estimated 380 million Christians. According to a 2006 Pew Forum on Religion and Public life study, 147 million African Christians were "renewalists" (Pentecostals and Charismatics).[37] According to David Barrett, most of the 552,000 congregations in 11,500 denominations throughout Africa in 1995 are completely unknown in the West.[38] Much of the recent Christian growth in Africa is now due to African evangelism and high birth rates, rather than European missionaries. Christianity in Africa shows tremendous variety, from the ancient forms of Oriental Orthodox Christianity in Egypt, Ethiopia, and Eritrea to the newest African-Christian denominations of Nigeria, a country that has experienced large conversion to Christianity in recent times. Several syncretistic and messianic sections have formed throughout much of the continent, including the Nazareth Baptist Church in South Africa and the Aladura churches in Nigeria. Some evangelical missions founded in Africa such as the UD-OLGC, founded by Evangelist Dag Heward-Mills, are also quickly spreading in influence all around the world. There are also fairly widespread populations of Seventh-day Adventists and Jehovah's Witnesses.

Some experts predict the shift of Christianity's center from the European industrialized nations to Africa and Asia in modern times. Yale University historian Lamin Sanneh stated that "African Christianity was not just an exotic, curious phenomenon in an obscure part of the world, but that African Christianity might be the shape of things to come."[39] The statistics from the World Christian Encyclopedia (David Barrett) illustrate the emerging trend of dramatic Christian growth on the continent and supposes, that in 2025 there will be 633 million Christians in Africa.[40]

A 2015 study estimates 2,161,000 Christian believers are from a formerly Muslim background in Africa, most of them belonging to some form of Protestantism.[41]

Statistics by Country

| Country | Christians | % Christian | GDP/Capita PPP World Bank 2012 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 380,000[26] | 2% | 1% | 1% | 8,515 | |

| 17,094,000 | 75%[42] | 50% | 25% | 6,105 | |

| 3,943,000 | 42.8% | 27% | 15% | 1,583 | |

| 1,416,000 | 71.6% | 5% | 66% | 16,986 | |

| 3,746,000 | 22.0% | 18% | 4% | 1,513 | |

| 7,662,000 | 75.0% | 60% | 15% | 560 | |

| 13,390,000 | 65.0% | 38.4% | 26.3% | 2,324 | |

| 487,000 | 89.1%[43] | 78.7% | 10.4% | 4,430 | |

| 2,302,000 | 80% | 29% | 51% | 857 | |

| 4,150,000[43] | 35.0% | 20% | 15% | 1,493 | |

| 15,000 | 2.1% | 1,230 | |||

| 3,409,000 | 90.7% | 50% | 40% | 4,426 | |

| 63,150,000 | 92% | 50% | 42% | 422 | |

| 7,075,000 | 32.8% | 28.9% | 3.9% | 2,039 | |

| 53,000 | 6.0% | 1% | 5% | 2,784 | |

| 9,029,000 | 10.0% [44] | 6,723 | |||

| 683,000 | 88.7%[43] | 80.7% | 8.0% | 30,233 | |

| 2,871,000 | 63%[45] | 4% | 54% | 566 | |

| 52,580,000 | 64% | 0.7% | 63.4% | 1,139 | |

| 1,081,000 | 88.0%[46] | 41.9% | 46.1% | 16,086 | |

| 79,000 | 4.2% [47] | 1,948 | |||

| 19,300,000 | 71.2%[48] | 13.1% | 58.1% | 2,048 | |

| 1,032,000 | 8.9% [49] | 5% | 5% | 1,069 | |

| 165,000 | 10.0% | 10.0% | 1,192 | ||

| 34,774,000 | 85.1% | 23.4% | 61.7% | 1,761 | |

| 1,876,000 | 90.0% | 45% | 45% | 1,963 | |

| 1,391,000 | 85.5%[50] | 85.5% | 655 | ||

| 170,000[43] | 2.7%[43] | 0.5% | 1.5% | 17,665 | |

| 8,260,000 | 41.0% | 978 | |||

| 12,538,000 | 79.9% | 902 | |||

| 348,000 | 2.4% [51] | 1,214 | |||

| 5,000 | 0.14% | 2,603 | |||

| 418,000 | 32.2% | 15,649 | |||

| 336,000 | 1% [52] | 5,193 | |||

| 13,121,000 | 56.1% | 28.4% | 27.7% | 1,024 | |

| 1,991,000 | 90.0% | 13.7% | 76.3% | 7,488 | |

| 85,000 | 0.5% | 5% | 665 | ||

| 74,400,000-107,000,000 | 40% [53]- 58%[54] | 10–14,5% | 30–43,5% | 6,204 | |

| 9,619,000 | 93.6% | 56.9% | 26% | 1,354 | |

| 570,000 | 4.2% [55] | 1,944 | |||

| 80,000 | 94.7% | 82% | 15.2% | 27,008 | |

| 619,000-1,294,000 | 10%[56]-20.9%[57] | 1,359 | |||

| 1,000[58] | 0.01% | 0.0002% | 0.01% | ||

| 43,090,000 | 79.8%[59] | 5% | 75% | 11,440 | |

| 6,010,000[60] | 60.5%[61] | 30% | 30% | ||

| 525,000 | 1.5%[62] | ||||

| 31,342,000 | 61.4% [63] | 1,601 | |||

| 1,966,000 | 29.0% | 1,051 | |||

| 7,000 | 0.06% | 0.06% | 9,795 | ||

| 29,943,000 | 88.6% | 41.9% | 46.7% | 1,352 | |

| 200 | 0.04% | 0.04% | |||

| 12,939,000 | 95.5%[64] | 20.2% | 72.3% | 1712 | |

| 12,500,000 | 87.0%[65] | 17% | 63% | 559 | |

| Africa | 526,016,926 [66] | 62.7%[66] | 21.0%[67] | 41.7%[66] | - |

Denominations

Catholicism

Catholic Church membership rose from 2 million in 1900 to 140 million in 2000.[68] In 2005, the Catholic Church in Africa, including Eastern Catholic Churches, embraced approximately 135 million of the 809 million people in Africa. In 2009, when Pope Benedict XVI visited Africa, it was estimated at 158 million.[69] Most belong to the Latin Church, but there are also millions of members of the Eastern Catholic Churches.

Orthodoxy

- Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church – 37 million[70][71][72][73][74]

- Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria – 10 million[75][76][77][78]

- Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church - 2 million[79]

- Greek Orthodox Church of Alexandria – 0.5 million[80]

Protestantism

Anglicanism

- Church of Nigeria – 20.1 million[81]

- Church of Uganda – 8.1 million[82]

- Anglican Church of Kenya – 5.0 million[83]

- Episcopal Church of South Sudan and Sudan – 4.5 million[84]

- Anglican Church of Southern Africa – 2.3 million[16]

- Anglican Church of Tanzania – 2.0 million[85]

- Anglican Church of Rwanda – 1.0 million[86]

- Church of the Province of Central Africa – 0.9 million[87]

- Anglican Church of Burundi – 0.8 million[88]

- Church of Christ in Congo–Anglican Community of Congo – 0.5 million[89]

- Church of the Province of West Africa – 0.3 million[90]

- Reformed Evangelical Anglican Church of South Africa – 0.09 million[91]

Baptists

- Nigerian Baptist Convention – 5.0 million[92]

- Baptist Union of Uganda – 2.5 million[92]

- Baptist Community of Congo – 2.1 million[92]

- Baptist Convention of Tanzania – 2.0 million[92]

- Baptist Community of the Congo River – 1.1 million[92]

- Baptist Convention of Kenya – 0.6 million[92]

- Baptist Convention of Malawi – 0.3 million[92]

- Ghana Baptist Convention – 0.3[92]

- Union of Baptist Churches in Rwanda – 0.3 million[92]

- Evangelical Baptist Church of the Central African Republic – 0.2 million[92]

Lutheranism

- Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus – 8.3 million[93]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in Tanzania – 6.5 million[94]

- Malagasy Lutheran Church – 3.0 million[95]

- The Lutheran Church of Christ in Nigeria – 2.2 million[96]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in Namibia – 0.7 million[97]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in Southern Africa – 0.6 million[98]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in the Republic of Namibia – 0.4 million[97]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church of Cameroon – 0.3 million[99]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in Zimbabwe – 0.3 million[100]

Methodism

- Methodist Church Nigeria – 2 million[101]

- Methodist Church of Southern Africa – 1.7 million[102]

- United Methodist Church of Ivory Coast – 1 million[103]

- Methodist Church Ghana – 0.8 million[104]

- Methodist Church in Kenya – 0.5 million[105]

Reformed (Calvinism)

- Presbyterian Church of East Africa – 4.0 million[106]

- Presbyterian Church of Nigeria – 3.8 million[107]

- Presbyterian Church of Africa – 3.4 million[108]

- Church of Christ in Congo–Presbyterian Community of Congo – 2.5 million[109]

- Presbyterian Church of Cameroon – 1.8 million[110]

- Church of Central Africa Presbyterian – 1.3 million[111]

- Presbyterian Church in Sudan – 1.0 million[112]

- Presbyterian Church in Cameroon – 0.7 million[113]

- Evangelical Presbyterian Church, Ghana – 0.6 million[114]

- Uniting Presbyterian Church in Southern Africa – 0.5 million[115]

- Presbyterian Church in Rwanda – 0.3 million[116]

- Church of Jesus Christ in Madagascar – 3.5 million[117]

- United Church in Zambia – 3.0 million[118]

- Evangelical Church of Cameroon – 2.5 million[119]

- Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa (NGK) – 1.1 million

- Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa – 0.5 million[120]

- Lesotho Evangelical Church – 0.3 million[121]

- Christian Reformed Church of Nigeria – 0.3 million[122]

- Reformed Church in Zambia – 0.3 million[123]

- Evangelical Reformed Church in Angola – 0.2 million[124]

- Church of Christ in the Sudan Among the Tiv – 0.2 million[125]

- Evangelical Church of Congo – 0.2 million[126]

- Evangelical Congregational Church in Angola – 0.9 million[127]

- United Congregational Church of Southern Africa – 0.5 million[128]

Pentecostalism

- Apostolic Faith Mission of South Africa – 1.2 million

- Association of Pentecostal Churches of Rwanda – 1 million

African initiated churches

60 million people are members of African initiated churches.[129]

- Zion Christian Church – 15 million

- Eternal Sacred Order of Cherubim and Seraphim – 10 million

- Kimbanguist Church – 5.5 million

- Redeemed Christian Church of God – 5 million[130]

- Church of the Lord (Aladura) – 3.6 million[131]

- Council of African Instituted Churches – 3 million[132]

- Church of Christ Light of the Holy Spirit – 1.4 million[133]

- African Church of the Holy Spirit – 0.7 million[134]

- African Israel Church Nineveh – 0.5 million[135]

- New Apostolic Church, The New Apostolic Church has around 10 million members.[136]

See also

- African theology

- Afrikaner Calvinism

- Christian mysticism in ancient Africa

- Roman Catholicism in Africa

- Traditional African religion

References

- http://www.africanchristian.org African Christianity

- Olga Cecilia Méndez González (April 2013). Thirteenth Century England XIV: Proceedings of the Aberystwyth and Lampeter Conference, 2011. Orbis Books. ISBN 9781843838098., page 103-104

- E.J. Brill's First Encyclopedia of Islam 1913-1936, Volume 5. BRILL. 1993. ISBN 9004097910.

- Rosalind Shaw, Charles Stewart, Syncretism/Anti-Syncretism: The Politics of Religious Synthesis (1994)

- Johnson, Todd M.; Zurlo, Gina A.; Hickman, Albert W.; Crossing, Peter F. (November 2017). "Christianity 2018: More African Christians and Counting Martyrs". International Bulletin of Mission Research. 42 (1): 20–28. doi:10.1177/2396939317739833. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Mauro, J.-P. (24 July 2018). "Africa overtakes Latin America for the highest Christian population". Aleteia — Catholic Spirituality, Lifestyle, World News, and Culture. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Eusebius of Caesarea, the author of Ecclesiastical History in the 4th century, states that St. Mark came to Egypt in the first or third year of the reign of Emperor Claudius, i.e. 41 or 43 A.D. "Two Thousand years of Coptic Christianity", Otto F.A. Meinardus, p.28.

- Jakobielski, S. Christian Nubia at the Height of its Civilization (Chapter 8). UNESCO. University of California Press. San Francisco, 1992. ISBN 9780520066984

- Oden, Thomas C. How Africa shaped the Christian Mind, IVP 2007.

- Der Nahe und Mittlere Osten By Heinz Halm, page 99

- Ancient African Christianity: An Introduction to a Unique Context and Tradition By David E. Wilhite, page 332-334

- Ancient African Christianity: An Introduction to a Unique Context and Tradition By David E. Wilhite, page 336-338

- The Disappearance of Christianity from North Africa in the Wake of the Rise of Islam C. J. Speel, II Church History, Vol. 29, No. 4 (December, 1960), pp. 379-397

- "Office of the President - Bethel University". Archived from the original on 2007-02-02.

- Prevost, Virginie (1 December 2007). "Les dernières communautés chrétiennes autochtones d'Afrique du Nord". Revue de l'histoire des religions (4): 461–483. doi:10.4000/rhr.5401 – via rhr.revues.org.

- Phillips, Fr Andrew. "The Last Christians Of North-West Africa: Some Lessons For Orthodox Today". www.orthodoxengland.org.uk.

- Eleanor A. Congdon (2016-12-05). Latin Expansion in the Medieval Western Mediterranean. Routledge. ISBN 9781351923057.

- Hrbek, Ivan (1992). Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century. Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa. J. Currey. p. 34. ISBN 0852550936.

- Lamin Sanneh (2012). West African Christianity: The Religious Impact. Orbis Books. ISBN 9789966150691.

- Ibben Fonnesberg-Schmidt (2013-09-10). Reconquest and Crusade in Medieval Spain. BRILL. ISBN 0812203062.

- Ibben Fonnesberg-Schmidt (2013-09-10). martin morocco&f=false Reconquest and Crusade in Medieval Spain Check

|url=value (help). BRILL. ISBN 0812203062., page 117-20 - Lamin Sanneh (2015-03-24). West African Christianity: The Religious Impact. Orbis Books. ISBN 9781608331499.

- Kevin Shillington (January 1995). West African Christianity: The Religious Impact. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 9781137524812.

- Cook, Bernard A. (2001). Europe since 1945: an encyclopedia. New York: Garland. pp. 398. ISBN 0-8153-4057-5.

- "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census | Duane A Miller Botero - Academia.edu". academia.edu. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2008, U.S Department of State

- Converted Christians in Morocco Need Prayers Archived 2013-02-21 at Archive.today

- International Religious Freedom Report 2010: Tunisia. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (November 17, 2010). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Mkenda, Festo. “Jesuits, Protestants, and Africa before the Twentieth Century.” Encounters between Jesuits and Protestants in Africa, edited by Festo Mkenda and Robert Aleksander Maryks, vol. 13, Brill, LEIDEN; BOSTON, 2018, pp. 11–30. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctvbqs62t.4.

- Mazrui, Ali A. “Religion and Political Culture in Africa.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, vol. 53, no. 4, 1985, pp. 817–839. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1464277.

- Engelke, Matthew. “The Book, the Church and the 'Incomprehensible Paradox': Christianity in African History.” Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 29, no. 1, 2003, pp. 297–306. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3557421.

- Kollman, Paul. “Classifying African Christianities: Past, Present, and Future: Part One.” Journal of Religion in Africa, vol. 40, no. 1, 2010, pp. 3–32., www.jstor.org/stable/20696840.

- Jenkins, Philip (29 May 2020). "What happened in Africa after the pandemic of 1918". The Christian Century. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Mkenda, Festo. “Jesuits, Protestants, and Africa before the Twentieth Century.” Encounters between Jesuits and Protestants in Africa, edited by Festo Mkenda and Robert Aleksander Maryks, vol. 13, Brill, LEIDEN; BOSTON, 2018, pp. 11–30. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctvbqs62t.4.

- Mazrui, Ali A. “Religion and Political Culture in Africa.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, vol. 53, no. 4, 1985, pp. 817–839. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1464277.

- "Gospel Riches, Africa's rapid embrace of prosperity Pentecostalism provokes concern and hope", Christianity Today, July 2007

- See "Ecclesiastical Cartography and the Invisible Continent: The Dictionary of African Christian Biography" at http://www.dacb.org/xnmaps.html Archived 2010-01-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Historian Ahead of His Time", Christianity Today, February 2007

- World Council of Churches Report, August 2004

- Johnstone, Patrick; Miller, Duane (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR. 11: 14. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- Viegas, Fátima (2008) Panorama das Religiões em Angola Independente (1975–2008), Ministério da Cultura/Instituto Nacional para os Assuntos Religiosos, Luanda

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- http://www.globalreligiousfutures.org/countries/eritrea

- "Africa :: GABON". CIA The World Factbook.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- "International Religious Freedom Report 2010: Liberia". United States Department of State. November 17, 2010. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- Dominique Lewis (May 2013). "Nigeria Round 5 codebook (2012)" (PDF). Afrobarometer. Afrobarometer. p. 62. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- "The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- "Almost expunged: Somalia's Embattled Christians". 2009-10-22. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- StatsSA National Census results 2012 http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/SAStatistics/SAStatistics2012.pdf

- "Table: Religious Composition by Country, in Numbers". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 18 December 2012. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "Table: Religious Composition by Country, in Percentages". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 18 December 2012. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- "The World Factbook". cia.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- "CIA Site Redirect — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- Zambia - 2010 Census of Population and Housing Archived 2016-01-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Religious composition by country, Pew Research, Washington DC (2012)

- The Global Catholic Population, Pew Research CenterReligion & Public Life

- The Catholic Explosion Archived 2011-11-14 at the Wayback Machine, Zenit News Agency, 11 November 2011

- Rachel Donadio, "On Africa Trip, Pope Will Find Place Where Church Is Surging Amid Travail," New York Times, 16 March 2009.

- "Orthodox Christianity in the 21st Century". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 8 November 2017.

Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church has an estimated 36 million adherents, nearly 14% of the world’s total Orthodox population.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Population Census Commission (4 June 2012). "Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census Results" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church | church, Ethiopia". Encyclopedia Britannica.

In the early 21st century the church claimed more than 30 million adherents in Ethiopia.

- "Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church — World Council of Churches". www.oikoumene.org.

- "Ethiopia: An outlier in the Orthodox Christian world". Pew Research Center.

- "Orthodox Christianity in the 21st Century". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 8 November 2017.

Egypt has the Middle East’s largest Orthodox population (an estimated 4 million Egyptians, or 5% of the population), mainly members of the Coptic Orthodox Church.

- "BBC - Religions - Christianity: Coptic Orthodox Church". www.bbc.co.uk.

The Coptic Orthodox Church is the main Christian Church in Egypt, where it has between 6 and 11 million members.

- CNN, Matt Rehbein. "Who are Egypt's Coptic Christians?". CNN.

- "Coptic Orthodox Church — World Council of Churches". www.oikoumene.org.

- "Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church — World Council of Churches". www.oikoumene.org.

- "Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria and All Africa — World Council of Churches". www.oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 6 October 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- "Church of Nigeria". Anglican-nig.org. 18 April 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Church of Uganda". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Anglican Church of Kenya". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Archived 20 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Anglican Church of Tanzania". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Province of the Episcopal Church in Rwanda". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Church of the Province of Central Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Anglican Church of Burundi". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Church of Christ in Congo – Anglican Community of Congo". Oikoumene.org. 20 December 2003. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Church of the Province of West Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "South African Christian". Sachristian.co.za. Archived from the original on 20 June 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "Baptist World Alliance - Statistics". www.bwanet.org. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus". News and Events. EECMY. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Tanzania | The Lutheran World Federation". www.lutheranworld.org. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "Madagascar | The Lutheran World Federation". www.lutheranworld.org. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "Nigeria | The Lutheran World Federation". www.lutheranworld.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "Namibia | The Lutheran World Federation". www.lutheranworld.org. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "South Africa | The Lutheran World Federation". www.lutheranworld.org. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "Cameroon | The Lutheran World Federation". www.lutheranworld.org. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "Zimbabwe | The Lutheran World Federation". www.lutheranworld.org. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "Methodist Church Nigeria". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Methodist Church of Southern Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "United Methodist Church of Ivory Coast". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Methodist Church Ghana". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Methodist Church in Kenya". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Presbyterian Church of East Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Presbyterian Church of Nigeria". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "Presbyterian Church of Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Church of Christ in Congo – Presbyterian Community of Congo". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Presbyterian Church of Cameroon". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Patrick Johnstone and Jason Mandryk, Operation World: 21st Century Edition (Paternoster, 2001), p. 419 Archived 31 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- Archived 21 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Presbyterian Church in Cameroon". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Presbyterian Church of Ghana". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Uniting Presbyterian Church in Southern Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Presbyterian Church in Rwanda". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Church of Jesus Christ in Madagascar (FJKM)". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "United Church of Zambia". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Administrator. "Qui sommes-nous?". Eeccameroun.org. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Lesotho Evangelical Church". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Reformed Church of Christ in Nigeria". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 September 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Reformed Church in Zambia". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Evangelical Reformed Church of Angola". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "The Church of Christ in the Sudan among the Tiv (NKST)". Recweb.org. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Evangelical Church of Congo". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Evangelical Congregational Church in Angola". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "United Congregational Church of Southern Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Gordon Melton. "African Initiated Churches". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "Redemption Camp | Armin Rosen". First Things. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- "Church of the Lord (Aladura) Worldwide". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Council of African Instituted Churches". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Church of Christ Light of the Holy Spirit". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "African Church of the Holy Spirit". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 9 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "African Israel Nineveh Church". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "New Apostolic Church International". Nak.org. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christianity in Africa. |