Cetbang

The Cetbang (also known as bedil, warastra, or coak) was a type of cannon produced and used by the Majapahit Empire (1293–1527) and other kingdoms in the Indonesian archipelago. The cetbang is a breech-loading cannon, it is different from typical European and Middle Eastern cannons, which are usually muzzleloader. In the Sekar inscription it states that the main production foundries of cetbang were in Rajekwesi, Bojonegoro, whereas the black powder was produced in Swatantra Biluluk (Lamongan).[1][2] Several examples survive and are exhibited as tourist attractions or in museums.

Etymology

Cetbang was originally called a bedil.[3][4] It is also called a warastra.[5]:246 In Java, the term for cannon is called bedil,[6] but this term may refer to various type of firearms and gunpowder weapon, from small matchlock pistol to large siege guns. The term bedil comes from wedil (or wediyal) and wediluppu (or wediyuppu) in Tamil language.[7] In its original form, these words refer to gunpowder blast and saltpeter, respectively. But after being absorbed into bedil in Malay language, and in a number of other cultures in the archipelago, that Tamil vocabulary is used to refer to all types of weapons that use gunpowder. In Javanese and Balinese the term bedil and bedhil is known, in Sundanese the term is bedil, in Batak it is known as bodil, in Makasarese, badili, in Buginese, balili, in Dayak language, badil, in Tagalog, baril, in Bisayan, bádil, in Bikol languages, badil, and Malay people call it badel or bedil.[7][8][9] The term "meriam coak" is from the Betawi language, it means "hollow cannon", referring to the breech.[10] It is also simply referred to as coak.[11]

Description

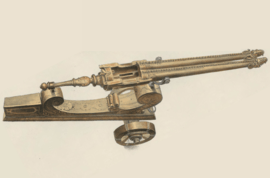

Early cetbang is made from bronze, and is a breech-loaded weapon. In the 16th century, iron is also used.[11][12] The size of cetbang used by the Majapahit navy varied from one to three meters in length. The three-meter-long cetbang was usually used by the larger ships in the Majapahit navy (see Djong). However, most of these guns had small bores (30 to 60 mm). They are light, mobile cannons, most of them can be carried and shot by one man.[13] These gun are mounted on swivel yoke (called cagak), the spike is fitted into holes or sockets in the bulwarks of a ship or the ramparts of a fort.[14] A tiller of wood is inserted to the back of the cannon with rattan, to enable it to be trained and aimed.[13]

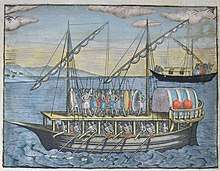

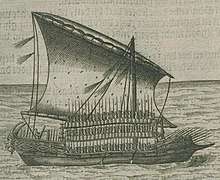

Cetbang can be mounted as fixed gun, swivel gun, or placed in a wheelled carriage. Small sized cetbang can be easily installed on small vessels called Penjajap (Portuguese: Pangajaua or Pangajava) and Lancaran. This gun is used as an anti-personnel weapon, not anti-ship. In this age, even to the 17th century, the Nusantaran soldiers fought on a platform called Balai (see picture of ship below) and perform boarding actions. Loaded with scattershots (grapeshot, case shot, or nails and stones) and fired at close range, the cetbang is very effective at this type of fighting.[5]:241[15]

History

Majapahit era (ca. 1300-1478)

Cannons were introduced to Majapahit when Kublai Khan's Chinese army under the leadership of Ike Mese sought to invade Java in 1293. History of Yuan mentioned that the Mongol used cannons (Chinese: Pao) against Daha forces.[16] The Majapahit Kingdom dominated the Nusantara archipelago primarily because it possessed the technology to cast and forge bronze on an early mass production basis. The Majapahit also pioneered the manufacturing and usage of gunpowder weapons on a large scale. The Majapahit Empire was one of the last major empires of the region and is considered to be one of the most powerful empires in the history of Indonesia and Southeast Asia. Thomas Stamford Raffles wrote in The History of Java that in 1247 çaka (1325 AD), cannons have been widely used in Java especially by the Majapahit. It is recorded that the small kingdoms in Java that that sought the protection of Majapahit had to hand over their cannons to the Majapahit.[17]:106[18] Majapahit under Mahapatih (prime minister) Gajah Mada (in office 1329-1364) utilized gunpowder technology obtained from Yuan dynasty for use in naval fleet.[19]:57 One of the earliest reference to cannon and artillerymen in Java is from the year 1346.[20]

The use of cannons was widespread in the Majapahit navy, amongst pirates, and in neighboring kingdoms in Nusantara.[21] A famous Majapahit admiral, Mpu Nala, was renowned for his use of cannons. Records of Mpu Nala are known from the Sekar inscription, the Mana I Manuk (Bendosari) inscription, the Batur inscription, and the Tribhuwana inscription which referred to him as Rakryan Tumenggung (war commander).[22] The neighboring kingdom of Sunda was recorded using bedil during battle of Bubat of 1357. Kidung Sunda canto 2 verse 87-95 mentioned that the Sundanese had juru-modya ning bedil besar ing bahitra (aimer/operator of the big cannon) on the ships in the river near Bubat square. Majapahit troops situated close to the river were unlucky: The corpses could hardly be called corpses, they were maimed, torn apart in the most gruesome way, the arms and the heads were thrown away. The cannon balls were said to discharge like rain, which forced the Majapahit troops to retreat in the first part of the battle.[23]

Ma Huan (Zheng He's translator) visited Java in 1413 and took notes about the local customs. His book, Yingya Shenlan, mentioned that cannons are fired in Javanese marriage ceremonies when the husband was escorting his new wife to the marital home to the sound of gongs, drums, and firecrackers.[5]:245

Majapahit decline and the rise of Islam (1478-1600)

Following the decline of the Majapahit, particularly after the paregreg civil war (1404-1406),[24]:174-175 the consequent decline in demand for gunpowder weapons caused many weapon makers and bronze-smiths to move to Brunei, Sumatra, the Malay peninsula, or the Philippines. This spread the production and usage of the cetbang, especially for protecting trade ships in the Makassar Strait from pirates. It led to near universal use of the swivel-gun and cannons in the Nusantara archipelago.[21] When the Portuguese first came to Malacca, they found a large colony of Javanese merchants under their own headmen; the Javanese were manufacturing their own cannon, which then, and for long after, were as necessary to merchant ships as sails.[25]

When Iberian explorer came to Southeast Asia, the local population was unimpressed with the might and power of the heavily armed trading vessels of Portugal and Spain. De Barros mentions that with the fall of Malacca (1511), Albuquerque captured 3,000 out of 8,000 artillery. Among those, 2,000 were made from brass and the rest from iron. All the artillery is of such excellent workmanship that it could not be excelled, even in Portugal. – Commentarios do grande Afonso de Albuquerque, Lisbon 1576.[26][27] The cannons found were of various types: esmeril (1/4 to 1/2-pounder swivel gun,[28] probably refers to cetbang or lantaka), falconet (cast bronze swivel gun larger than the esmeril, 1 to 2-pounder,[28] probably refers to lela), medium saker (long cannon or culverin between a six and a ten pounder, probably refers to meriam),[29] and bombard (short, fat, and heavy cannon).[30]:46 The Malays also has 1 beautiful large cannon sent by the king of Calicut.[30]:47[31]:22 The large number of artillery in Malacca come from various sources in the Nusantara archipelago: Pahang, Java, Brunei, Minangkabau, and Aceh.[32][33][34]

Cetbang cannons were further improved and used in the Demak Sultanate period during the Demak invasion of Portuguese Malacca (1513). During this period, the iron, for manufacturing Javanese cannons was imported from Khorasan in northern Persia. The material was known by Javanese as wesi kurasani (Khorasan iron).[12] When the Portuguese came to the archipelago, they referred to it as Berço, which was also used to refer to any breech-loading swivel gun, while the Spaniards call it Verso.[15]

Colonial era (1600-1945)

When the Dutch captured Makassar's fort of Somba Opu (1669), they seized 33 large and small bronze cannon, 11 cast-iron cannon, 145 base (breech-loading swivel gun) and 83 breech-loading gun chamber, 60 muskets, 23 arquebuses, 127 musket barrels, and 8483 bullets.[35]:384

Bronze breech-loading swivel guns, called ba'dili,[36][37] is brought by Makassan sailor in trepanging voyage to Australia. Matthew Flinders recorded the use of small cannon on board Makassan perahu off the Northern Territory in 1803.[38] Vosmaer (1839) writes that Makassan fishermen sometimes took their small cannon ashore to fortify the stockades they built near their processing camps to defend themselves against hostile Aborigines.[39] Dyer (ca. 1930) noted the use of cannon by Makassans, in particular the bronze breechloader with 2 inch (50.8 mm) bore.[40]

The Americans fought Moros equipped with breech-loading swivel guns in the Philippines in 1904.[13] These guns are usually referred to as lantaka or breech-loading lantaka.[41]

Surviving examples

There are surviving examples of the cetbang at:

- The Bali Museum, Denpasar, Bali. This Balinese cannon is located in the yard of Bali Museum.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. This cannon is thought to have been produced in the 14th century, made from bronze with dimensions of 37.7 inches (96 cm) x 16 inches (41 cm).[42]

- Luis de Camoes museum in Macau has a piece of highly ornamented cetbang. Year manufactured is unknown.

- Talaga Manggung museum, Majalengka, West Java. Numerous cetbang is in good condition due to routine cleaning ritual.[43]

- Some cetbang can be found in National Museum of Anthropology at Manila, including one medium-sized cannon on fixed mount.

- Fatahillah Museum has a meriam coak labelled as "Cirebon cannon", in a fixed, highly ornamented mount. The whole mount is 234 cm in length, 76 cm in width, and 79 cm in height.[44]

- Several examples and parts of cetbang can be found in Rijksmuseum, Netherlands, labelled as lilla (lela cannon).

- A cetbang is found in Beruas river, Perak, in 1986. Now it is exhibited in Beruas museum.[45]

Cetbang are also found at:

- Dundee beach, Northern Territory, Australia. Researchers have concluded that this bronze swivel cannon is from the 16th century, before James Cook's voyage to Australia. The model is closer to the Ternate, Makassar, or Balinese cannons.[11]

- Bissorang village, Selayar islands, Sulawesi Selatan province. This cannon is thought to have originated from the Majapahit era. Local people call this cetbang Ba'dili or Papporo Bissorang.[36][37]

- A Mataram-era (1587–1755) cetbang can be found at Lubuk Mas village, South Sumatera, Indonesia.[46]

- A 4-wheeled cetbang can be found at Istana Panembahan Matan in Mulia Kerta, West Kalimantan.[47]

- Two cannons can be found in Elpa Putih villlage, Amahai sub-district, Central Maluku Regency. It is thought to have originated from 16-17th century Javanese Islamic kingdoms.[48]

Gallery

A cetbang found on Selayar island

A cetbang found on Selayar island Cetbang in Bali Museum. Length: 1833 mm. Bore: 43 mm. Length of tiller: 315 mm. Widest part: 190 mm (at the base ring).

Cetbang in Bali Museum. Length: 1833 mm. Bore: 43 mm. Length of tiller: 315 mm. Widest part: 190 mm (at the base ring). San Diego gallery, Philippines National Museum of Anthropology. The leftmost cannon is a medium sized cetbang in fixed mount

San Diego gallery, Philippines National Museum of Anthropology. The leftmost cannon is a medium sized cetbang in fixed mount A bronze sacred gun in Java, with breech-block, ca. 1866. Malay women come and settle accounts with the tutelary deity of this gun, and pray for children.

A bronze sacred gun in Java, with breech-block, ca. 1866. Malay women come and settle accounts with the tutelary deity of this gun, and pray for children. Breech-loading "lilla", Rijksmuseum, ca. 1750 - 1850. Length 180.5 cm, width 21.5 cm, calibre: 4.5 cm, weight: 120.8 kg.

Breech-loading "lilla", Rijksmuseum, ca. 1750 - 1850. Length 180.5 cm, width 21.5 cm, calibre: 4.5 cm, weight: 120.8 kg. Meriam coak dubbed "Cirebon cannon" of Jakarta History Museum (Fatahillah Museum).

Meriam coak dubbed "Cirebon cannon" of Jakarta History Museum (Fatahillah Museum).

See also

- Bedil tombak

- Lantaka

- Breech-loading swivel gun

- Java arquebus, a type of firearm also called a bedil

- Timeline of the gunpowder age

- History of gunpowder

- History of cannon

References

- Dr. J.L.A. Brandes, T.B.G., LII (1910)

- Hino (21 May 2016). "Senjata Ini Jadi Bukti Kekuatan Kerajaan Majapahit Memang Disegani Dunia". Suratkabar.id. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- "Mengejar Jejak Majapahit di Tanadoang Selayar - Semua Halaman - National Geographic". nationalgeographic.grid.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- arthomoro. "MENGENAL CETBANG / MERIAM KERAJAAN MAJAPAHIT DARI JENIS , TIPE DAN FUNGSINYA ~ KOMPILASITUTORIAL.COM". Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1976). "L'Artillerie legere nousantarienne: A propos de six canons conserves dans des collections portugaises". Arts Asiatiques. 32: 233–268.

- Gardner, G. B. (1936). Keris and Other Malay Weapons. Singapore: Progressive Publishing Company.

- Kern, H. (January 1902). "Oorsprong van het Maleisch Woord Bedil". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 54: 311–312. doi:10.1163/22134379-90002058.

- Syahri, Aswandi (6 August 2018). "Kitab Ilmu Bedil Melayu". Jantung Melayu. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- Rahmawati, Siska (2016). "Peristilahan Persenjataan Tradisional Masyarakat Melayu di Kabupaten Sambas". Jurnal Pendidikan Dan Pembelajaran Khatulistiwa. 5.

- Singhawinata, Asep (27 March 2017). "Meriam Peninggalan Hindia Belanda". Museum Talagamanggung Online. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- Clark, Paul (2013). Dundee Beach Swivel Gun: Provenance Report. Northern Territory Government Department of Arts and Museums.

- Anonymous (2020). "Cetbang, Teknologi Senjata Api Andalan Majapahit". 1001 Indonesia. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576077702.

- "Cannons of the Malay Archipelago". www.acant.org.au. Retrieved 2020-01-25.

- Reid, Anthony (2012). Anthony Reid and the Study of the Southeast Asian Past. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4311-96-0.

- Song Lian. History of Yuan.

- Raffles, Thomas Stamford (1830). The History of Java. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street.

- Yusof, Hasanuddin (September 2019). "Kedah Cannons Kept in Wat Phra Mahathat Woramahawihan, Nakhon Si Thammarat". Jurnal Arkeologi Malaysia. 32: 59–75.

- Pramono, Djoko (2005). Budaya Bahari. Gramedia Pustaka Utama. ISBN 9789792213768.

- Beauvoir, Ludovic (1875). Voyage autour du monde: Australie, Java, Siam, Canton, Pekin, Yeddo, San Francisco. E. Plon.

- Thomas Stamford Raffles, The History of Java, Oxford University Press, 1965, ISBN 0-19-580347-7, 1088 pages.

- "PRASASTI SEKAR". penyuluhbudayabojonegoro.blogspot.co.id. Archived from the original on 2017-08-06. Retrieved 2017-08-06.

- Berg, C. C., 1927, Kidung Sunda. Inleiding, tekst, vertaling en aanteekeningen, BKI LXXXIII : 1-161.

- Hidayat, Mansur (2013). Arya Wiraraja dan Lamajang Tigang Juru: Menafsir Ulang Sejarah Majapahit Timur. Denpasar: Pustaka Larasan.

- Furnivall, J.S (2010). Netherlands India: A Study of Plural Economy. Cambridge University Press. p. 9

- A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands & Adjacent Countries. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- Manucy, Albert C. (1949). Artillery Through the Ages: A Short Illustrated History of the Cannon, Emphasizing Types Used in America. U.S. Department of the Interior Washington. p. 34.

- Lettera di Giovanni Da Empoli, with introduction and notes by A. Bausani, Rome, 1970, page 138.

- Charney, Michael (2004). Southeast Asian Warfare, 1300-1900. BRILL. ISBN 9789047406921.

- Crawfurd, John (1856). A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries. Bradbury and Evans.

- A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- Ismail, Norain B.T. (2012). Peperangan dalam Historiografi Johor: Kajian Terhadap Tuhfat Al-Nafis. Kuala Lumpur: Akademi Pengajian Islam Universiti Malaya.

- Ayob, Yusman (1995). Senjata dan Alat Tradisional. Selangor: Penerbit Prisma Sdn Bhd.

- Tarling, Nicholas (1992). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia: Volume 1, From Early Times to C.1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521355056.

- "kabarkami.com Is For Sale". www.kabarkami.com. Archived from the original on 2017-08-06. Retrieved 2017-08-06.

- Amiruddin, Andi Muhammad Ali (2017). Surga kecil Bonea Timur. Makassar: Pusaka Almaida. p. 15. ISBN 9786026253385.

- Flinders, Matthew (1814). A Voyage to Terra Australis. London: G & W Nichol.

- Vosmaer, J. N. (1839). "Korte beschrijving van het Zuid- Oostelijk schiereiland van Celebes, in het bijzonder van de Vosmaers-Baai of van Kendari". Verhandelingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kusten en Wetenschapen. 17: 63–184.

- Dyer, A. J. (1930). Unarmed Combat: An Australian Missionary Adventure. Edgar Bragg & Sons Pty. Ltd., printers 4-6 Baker Street Sydney.

- "National Museum of the Philippines, Part III (Museum of the Filipino People)". Wandering Bakya. 2014-08-15. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- "Cannon | Indonesia (Java) | Majapahit period (1296–1520) | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 2017-08-06.

- "Museum Talaga Manggung-Dinas Pariwisata dan Kebudayaan Provinsi Jawa Barat". www.disparbud.jabarprov.go.id. Retrieved 2018-06-30.

- "Museum Sejarah Jakarta". Rumah Belajar. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- Amran, A. Zahid (2018-09-22). "Kerajaan Melayu dulu dah guna senjata api berkualiti tinggi setaraf senjata buatan Jerman | SOSCILI". Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- Rawas, Sukandar. "Meriam kuno Lubuk Mas". Youtube.

- Rodee, Ab (11 August 2017). "Meriam Melayu". Picbear. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Handoko, Wuri (July 2006). "Meriam Nusantara dari Negeri Elpa Putih, Tinjauan Awal atas Tipe, Fungsi, dan Daerah Asal". Kapata Arkeologi. 2: 68–87.