Shield

A shield is a piece of personal armour held in the hand, which may or may not be strapped to the wrist or forearm. Shields are used to intercept specific attacks, whether from close-ranged weaponry or projectiles such as arrows, by means of active blocks, as well as to provide passive protection by closing one or more lines of engagement during combat.

.jpg)

Shields vary greatly in size and shape, ranging from large panels that protect the user's whole body to small models (such as the buckler) that were intended for hand-to-hand-combat use. Shields also vary a great deal in thickness; whereas some shields were made of relatively deep, absorbent, wooden planking to protect soldiers from the impact of spears and crossbow bolts, others were thinner and lighter and designed mainly for deflecting blade strikes. Finally, shields vary greatly in shape, ranging in roundness to angularity, proportional length and width, symmetry and edge pattern; different shapes provide more optimal protection for infantry or cavalry, enhance portability, provide secondary uses such as ship protection or as a weapon and so on.

In prehistory and during the era of the earliest civilisations, shields were made of wood, animal hide, woven reeds or wicker. In classical antiquity, the Barbarian Invasions and the Middle Ages, they were normally constructed of poplar tree, lime or another split-resistant timber, covered in some instances with a material such as leather or rawhide and often reinforced with a metal boss, rim or banding. They were carried by foot soldiers, knights and cavalry.

Depending on time and place, shields could be round, oval, square, rectangular, triangular, bilabial or scalloped. Sometimes they took on the form of kites or flatirons, or had rounded tops on a rectangular base with perhaps an eye-hole, to look through when used with combat. The shield was held by a central grip or by straps with some going over or around the user's arm and one or more being held by the hand.

Often shields were decorated with a painted pattern or an animal representation to show their army or clan. These designs developed into systematized heraldic devices during the High Middle Ages for purposes of battlefield identification. Even after the introduction of gunpowder and firearms to the battlefield, shields continued to be used by certain groups. In the 18th century, for example, Scottish Highland fighters liked to wield small shields known as targes, and as late as the 19th century, some non-industrialized peoples (such as Zulu warriors) employed them when waging war.

In the 20th and 21st century, shields have been used by military and police units that specialize in anti-terrorist actions, hostage rescue, riot control and siege-breaking.

Development of shields

Prehistory

The oldest form of shield was a protection device designed to block attacks by hand weapons, such as swords, axes and maces, or ranged weapons like sling-stones and arrows. Shields have varied greatly in construction over time and place. Sometimes shields were made of metal, but wood or animal hide construction was much more common; wicker and even turtle shells have been used. Many surviving examples of metal shields are generally felt to be ceremonial rather than practical, for example the Yetholm-type shields of the Bronze Age, or the Iron Age Battersea shield.

Ancient history

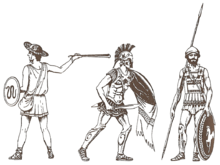

Size and weight varied greatly. Lightly armored warriors relying on speed and surprise would generally carry light shields (pelte) that were either small or thin. Heavy troops might be equipped with robust shields that could cover most of the body. Many had a strap called a guige that allowed them to be slung over the user's back when not in use or on horseback. During the 14th–13th century BC, the Sards or Shardana, working as mercenaries for the Egyptian pharaoh Ramses II, utilized either large or small round shields against the Hittites. The Mycenaean Greeks used two types of shields: the "figure-of-eight" shield and a rectangular "tower" shield. These shields were made primarily from a wicker frame and then reinforced with leather. Covering the body from head to foot, the figure-of-eight and tower shield offered most of the warrior's body a good deal of protection in hand-to-hand combat. The Ancient Greek hoplites used a round, bowl-shaped wooden shield that was reinforced with bronze and called an aspis. Another name for this type of shield is a hoplon. The hoplon shield inspired the name for hoplite soldiers. The hoplon was also the longest-lasting and most famous and influential of all of the ancient Greek shields. The Spartans used the aspis to create the Greek phalanx formation.[2] Their shields offered protection not only for themselves but for their comrades to their left.[3] Examples of Germanic wooden shields circa 350 BC – 500 AD survive from weapons sacrifices in Danish bogs.

The heavily armored Roman legionaries carried large shields (scuta) that could provide far more protection, but made swift movement a little more difficult. The scutum originally had an oval shape, but gradually the curved tops and sides were cut to produce the familiar rectangular shape most commonly seen in the early Imperial legions. Famously, the Romans used their shields to create a tortoise-like formation called a testudo in which entire groups of soldiers would be enclosed in an armoured box to provide protection against missiles. Many ancient shield designs featured incuts of one sort or another. This was done to accommodate the shaft of a spear, thus facilitating tactics requiring the soldiers to stand close together forming a wall of shields.

Post-classical history

Typical in the early European Middle Ages were round shields with light, non-splitting wood like linden, fir, alder or poplar, usually reinforced with leather cover on one or both sides and occasionally metal rims, encircling a metal shield boss. These light shields suited a fighting style where each incoming blow is intercepted with the boss in order to deflect it. The Normans introduced the kite shield around the 10th century, which was rounded at the top and tapered at the bottom. This gave some protection to the user's legs, without adding too much to the total weight of the shield. The kite shield predominantly features enarmes, leather straps used to grip the shield tight to the arm. Used by foot and mounted troops alike, it gradually came to replace the round shield as the common choice until the end of the 12th century, when more efficient limb armour allowed the shields to grow shorter, and be entirely replaced by the 14th century.

As body armour improved, knight's shields became smaller, leading to the familiar heater shield style. Both kite and heater style shields were made of several layers of laminated wood, with a gentle curve in cross section. The heater style inspired the shape of the symbolic heraldic shield that is still used today. Eventually, specialised shapes were developed such as the bouche, which had a lance rest cut into the upper corner of the lance side, to help guide it in combat or tournament. Free standing shields called pavises, which were propped up on stands, were used by medieval crossbowmen who needed protection while reloading.

In time, some armoured foot knights gave up shields entirely in favour of mobility and two-handed weapons. Other knights and common soldiers adopted the buckler, giving rise to the term "swashbuckler".[4] The buckler is a small round shield, typically between 8 and 16 inches (20–40 cm) in diameter. The buckler was one of very few types of shield that were usually made of metal. Small and light, the buckler was easily carried by being hung from a belt; it gave little protection from missiles and was reserved for hand-to-hand combat where it served both for protection and offence. The buckler's use began in the Middle Ages and continued well into the 16th century.

In Italy, the targa, parma and rotella were used by common people, fencers and even knights. The development of plate armour made shields less and less common as it eliminated the need for a shield. Lightly armoured troops continued to use shields after men-at-arms and knights ceased to use them. Shields continued in use even after gunpowder powered weapons made them essentially obsolete on the battlefield. In the 18th century, the Scottish clans used a small, round targe that was partially effective against the firearms of the time, although it was arguably more often used against British infantry bayonets and cavalry swords in close-in fighting.

During the 19th century, non-industrial cultures with little access to guns were still using war shields. Zulu warriors carried large lightweight shields called Ishlangu made from a single ox hide supported by a wooden spine.[5] This was used in combination with a short spear (assegai) and/or club. Other african shields include Glagwa from Cameroon or Nguba from Congo.

Modern history

Law enforcement shields

%2C_Special_Boat_Team_22_conducts_training_16_AUG_09.jpg)

Shields for protection from armed attack are still used by many police forces around the world. These modern shields are usually intended for two broadly distinct purposes. The first type, riot shields, are used for riot control and can be made from metal or polymers such as polycarbonate Lexan or Makrolon or boPET Mylar. These typically offer protection from relatively large and low velocity projectiles, such as rocks and bottles, as well as blows from fists or clubs. Synthetic riot shields are normally transparent, allowing full use of the shield without obstructing vision. Similarly, metal riot shields often have a small window at eye level for this purpose. These riot shields are most commonly used to block and push back crowds when the users stand in a "wall" to block protesters, and to protect against shrapnel, projectiles, molotov cocktails, and during hand-to-hand combat.

The second type of modern police shield is the bullet-resistant tactical shield. These shields are typically manufactured from advanced synthetics such as Kevlar and are designed to be bulletproof, or at least bullet resistant. Two types of shields are available:

- Light weight level IIIA shields that stop hand guns and submachine guns.

- Heavy Level III and IV shields that stop rifle rounds.

Tactical shields often have a firing port so that the officer holding the shield can fire a weapon while being protected by the shield, and they often have a bulletproof glass viewing port. They are typically employed by specialist police, such as SWAT teams in high risk entry and siege scenarios, such as hostage rescue and breaching gang compounds, as well as in antiterrorism operations. Tactical shields often have a large signs stating "POLICE" (or the name of a force, such as "US MARSHALS") to indicate that the user is a law enforcement officer.

Gallery

- Image from Hatshepsut's expedition to Punt showing Egyptians soldiers with shields (wood/animal skin). 15th century BC. Temple of Hathor Deir el-Bahari

A hoplite by painter Alkimachos, on an Attic red-figure vase, c. 460 BC. Shield has a curtain which serves as a protection from arrows.

A hoplite by painter Alkimachos, on an Attic red-figure vase, c. 460 BC. Shield has a curtain which serves as a protection from arrows. Sword and buckler(small shield) combat, plate from the Tacuinum Sanitatis illustrated in Lombardy, ca. 1390.

Sword and buckler(small shield) combat, plate from the Tacuinum Sanitatis illustrated in Lombardy, ca. 1390..jpg)

.jpg)

- Australian Aboriginal shield, Royal Albert Memorial Museum.

Nias ceremonial shield.

Nias ceremonial shield. Hippopotamus Hide Shield from Sudan. Currently housed at Westminster College in New Wilmington, Pennsylvania.

Hippopotamus Hide Shield from Sudan. Currently housed at Westminster College in New Wilmington, Pennsylvania.- Aboriginal bark shield collected in Botany Bay, New South Wales, during Captain Cook's first voyage in 1770, (British Museum).

See also

References

- Wood, J. G. (1870). The uncivilized races of men in all countries of the world. Рипол Классик. p. 115. ISBN 9785878634595.

- "Spartan Weapons". Ancientmilitary.com. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- "Spartan Military". Ancientmilitary.com. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- "The Sussex Rapier School". Hadesign.co.uk. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- "Zulu Shield (Longo)". Rrtraders.com. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

Bibliography

- Drummond, James (1890). "Notes on Ancient Shields and Highland Targets". Archaeologia Scotica. 5.

- Schulze, André(Hrsg.): Mittelalterliche Kampfesweisen. Band 2: Kriegshammer, Schild und Kolben. – Mainz am Rhein. : Zabern, 2007. – ISBN 3-8053-3736-1

- Snodgrass, A.M. "Arms and Armour of the Greeks." Cornell University Press, 1967

- "The Hoplite." The Classical Review, 61. 2011.

- Hellwag, Ursula. "Shield(s)." Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, Siegbert Uhllig (ed.), vol. 4, 650-651. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shields. |

| Look up shield in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Myarmoury.com, The Shield: An Abridged History of its Use and Development.

- Baronage.co.uk, The Shape of the Shield in heraldry.

- Era.anthropology.ac.uk, Shields: History and Terminology, Anthropological Analysis.

- Hadesign.co.uk, The Buckler, The Sussex Rapier School.

- Classical Greek Shield Patterns.