Bedil (term)

Bedil is a term from Nusantara area of Maritime Southeast Asia which refers to various type of firearms and gunpowder weapon, from small matchlock pistol to large siege guns. The term bedil comes from wedil (or wediyal) and wediluppu (or wediyuppu) in Tamil language.[1] In its original form, these words refer to gunpowder blast and saltpeter, respectively. But after being absorbed into bedil in Malay language, and in a number of other cultures in the archipelago, that Tamil vocabulary is used to refer to all types of weapons that use gunpowder. In Javanese and Balinese the term bedil and bedhil is known, in Sundanese the term is bedil, in Batak it is known as bodil, in Makasarese, badili, in Buginese, balili, in Dayak language, badil, in Tagalog, baril, in Bisayan, bádil, in Bikol languages, badil, and Malay people call it badel or bedil.[1][2][3]

History

The knowledge of gunpowder weapons were introduced to Javanese kingdom(s) when Kublai Khan's Chinese army under the leadership of Ike Mese sought to invade Java in 1293. History of Yuan mentioned that the Mongol used cannons (Chinese: Pao) against Daha forces.[4] Majapahit under Mahapatih (prime minister) Gajah Mada (in office 1329-1364) utilized gunpowder technology obtained from Yuan dynasty for use in naval fleet.[5]:57 One of the earliest reference to cannon and artillerymen in Java is from the year 1346.[6] Javanese breech-loading swivel gun, the cetbang, was originally known as bedil, a word that denotes any gunpowder-based weapon.[7]

Pole gun (bedil tombak) was recorded as being used by Java in 1413.[8][9]:245 However the knowledge of making "true" firearms came much later than the usage of swivel guns, after the middle of 15th century. It was brought by the Islamic nations of West Asia, most probably the Arabs. The precise year of introduction is unknown, but it may be safely concluded to be no earlier than 1460.[10]:23 This resulted in the development of Java arquebus, which was also called a bedil.[11] Portuguese influence to local weaponry, particularly after the capture of Malacca (1511), resulted in a new type of hybrid tradition matchlock firearm, the istinggar.[12]

Portuguese and Spanish invaders were unpleasantly surprised and even outgunned on occasion.[13] Duarte Barbosa recorded abundance of gunpowder-based weapons in Java ca. 1510. The Javanese were deemed as expert gun caster and good artillerymen. The weapon found there including one-pounder cannons, long muskets, spingarde (arquebus), schioppi (hand cannon), Greek fire, guns (cannons), and other fire-works.[14][15] When Malacca fell to the Portuguese in 1511 A.D., breech-loading swivel gun (cetbang) and muzzle-loading swivel gun (lela and rentaka) were found and captured by the Portuguese.[16]:50 In the battle, the Malays were using cannons, matchlock guns, and "firing tubes".[17] By early 16th century, the Javanese already locally-producing large guns, some of them still survived until the present day and dubbed as "sacred cannon" or "holy cannon". These cannons varied between 180-260-pounders, weighing anywhere between 3–8 tons, length of them between 3–6 m.[18]

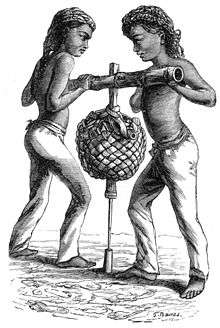

Saltpeter harvesting was recorded by Dutch and German travelers as being common in even the smallest villages and was collected from the decomposition process of large dung hills specifically piled for the purpose. The Dutch punishment for possession of non-permitted gunpowder appears to have been amputation.[19] Ownership and manufacture of gunpowder was later prohibited by the colonial Dutch occupiers.[20] According to colonel McKenzie quoted in Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles', The History of Java (1817), the purest sulfur was supplied from a crater from a mountain near the straits of Bali.[21]

For firearms using flintlock mechanism, the inhabitants of Nusantara archipelago is reliant on Western powers, as no local smith could produce such complex component.[22]:cxli[23][24]:42 and 50 These flintlock firearms are completely different weapon and were known by another name, senapan or senapang, from Dutch word snappaan.[25]:22 The gun-making areas of Nusantara could make these senapan, the barrel and the wooden part is made locally, but the mechanism is imported from the European colonist.[24]:42 and 50[26]:65[23]

List of weapon classified as bedil

Below are weapons historically may be referred to as bedil. Full description should be found in their respective pages. It is sorted alphabetically.

Bedil tombak

Locally-made pole gun-type hand cannon.

Cetbang

Early breech-loading swivel gun built by Javanese people.

Istinggar

A type of matchlock firearm, result of Portuguese influence to local weaponry, particularly after the capture of Malacca (1511).[12]

Java arquebus

Java arquebus is a primitive long matchlock firearm from Java, used before the arrival of Iberian explorers.

Lela

Lela is a type of cannon, similar but larger in dimension to rentaka.

Meriam

Formerly used for a kind of cannon, now it is de facto Malaysian and Indonesian term for cannon.[28][29]

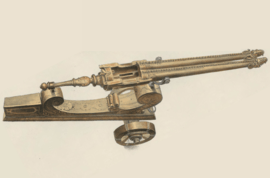

Miniature meriam kecil

Also known as currency cannon, this firearm is produced mainly for trading and novelty item.

Pemuras

Native name for blunderbuss.

References

- Kern, H. (January 1902). "Oorsprong van het Maleisch Woord Bedil". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 54: 311–312. doi:10.1163/22134379-90002058.

- Syahri, Aswandi (6 August 2018). "Kitab Ilmu Bedil Melayu". Jantung Melayu. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- Rahmawati, Siska (2016). "Peristilahan Persenjataan Tradisional Masyarakat Melayu di Kabupaten Sambas". Jurnal Pendidikan Dan Pembelajaran Khatulistiwa. 5.

- Song Lian. History of Yuan.

- Pramono, Djoko (2005). Budaya Bahari. Gramedia Pustaka Utama. ISBN 9789792213768.

- Beauvoir, Ludovic (1875). Voyage autour du monde: Australie, Java, Siam, Canton, Pekin, Yeddo, San Francisco. E. Plon.

- "Mengejar Jejak Majapahit di Tanadoang Selayar - Semua Halaman - National Geographic". nationalgeographic.grid.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- Mayers (1876). "Chinese explorations of the Indian Ocean during the fifteenth century". The China Review. IV: p. 178.

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1976). "L'Artillerie legere nousantarienne: A propos de six canons conserves dans des collections portugaises". Arts Asiatiques. 32: 233–268.

- Crawfurd, John (1856). A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries. Bradbury and Evans.

- Kern, H. (January 1902). "Oorsprong van het Maleisch Woord Bedil". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 54: 311–312. doi:10.1163/22134379-90002058.

- Andaya, L. Y. 1999. Interaction with the outside world and adaptation in Southeast Asian society 1500–1800. In The Cambridge history of southeast Asia. ed. Nicholas Tarling. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 345–401.

- Atsushi, Ota (2006). Changes of regime and social dynamics in West Java : society, state, and the outer world of Banten, 1750–1830. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15091-1.

- Barbosa, Duarte (1866). A Description of the Coasts of East Africa and Malabar in the Beginning of the Sixteenth Century. The Hakluyt Society.

- Partington, J. R. (1999). A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5954-0.

- Charney, Michael (2004). Southeast Asian Warfare, 1300-1900. BRILL. ISBN 9789047406921.

- Gibson-Hill, C. A. (July 1953). "Notes on the old Cannon found in Malaya, and known to be of Dutch origin". Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 26: 145–174 – via JSTOR.

- Modern Asian Studies. Vol. 22, No. 3, Special Issue: Asian Studies in Honour of Professor Charles Boxer (1988), pp. 607–628 (22 pages).

- Raffles, Thomas Stamford (1978). The History of Java ([Repr.]. ed.). Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-580347-1.

- Dipanegara, P.B.R. Carey, Babad Dipanagara: an account of the outbreak of the Java war, 1825–30 : the Surakarta court version of the Babad Dipanagara with translations into English and Indonesian volume 9: Council of the M.B.R.A.S. by Art Printing Works: 1981.

- Thomas Stamford Raffles, The History of Java, Oxford University Press, 1965 (originally published in 1817), ISBN 0-19-580347-7

- Raffles, Sir Thomas Stamford (1830). The History of Java, Volume 2. Java: J. Murray.

- Egerton, W. (1880). An Illustrated Handbook of Indian Arms. W.H. Allen.

- Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66370-0.

- Crawfurd, John (1856). A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries. Bradbury and Evans.

- Dasuki, Wan Mohd (2014). "Malay Manuscripts on Firearms as an Ethnohistorical Source of Malay Firearms Technology". Jurnal Kemanusiaan. 21: 53–71.

- Teoh, Alex Eng Kean (2005). The Might of the Miniature Cannon A treasure of Borneo and the Malay Archipelago. Asean Heritage.

- Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (2014). Kamus Dewan Edisi Keempat. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.

- Departemen Pendidikan Nasional (2008). Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia Pusat Bahasa Edisi Keempat. Jakarta: PT Gramedia Pustaka Utama.