Composite material

A composite material (also called a composition material or shortened to composite, which is the common name) is a material made from two or more constituent materials with significantly different physical or chemical properties that, when combined, produce a material with characteristics different from the individual components. The individual components remain separate and distinct within the finished structure, differentiating composites from mixtures and solid solutions.[1][2]

The new material may be preferred for many reasons. Common exam include materials which are stronger, lighter, or less expensive when compared to traditional materials.

More recently, researchers have also begun to actively include sensing, actuation, computation and communication into composites,[3] which are known as Robotic Materials.[4]

Typical engineered composite materials include:

- Reinforced concrete and masonry

- Composite wood such as plywood

- Reinforced plastics, such as fibre-reinforced polymer or fiberglass

- Ceramic matrix composites (composite ceramic and metal matrices)

- Metal matrix composites

- and other Advanced composite materials

Composite materials are generally used for buildings, bridges, and structures such as boat hulls, swimming pool panels, racing car bodies, shower stalls, bathtubs, storage tanks, imitation granite and cultured marble sinks and countertops.

The most advanced examples perform routinely on spacecraft and aircraft in demanding environments.[5]

History

The earliest synthetic composite materials were made from straw and mud combined to form bricks for building construction. Ancient brick-making was documented by Egyptian tomb paintings.

Wattle and daub is one of the oldest synthetic composite materials, at over 6000 years old.[6] Concrete is also a composite material, and is used more than any other synthetic material in the world. As of 2006, about 7.5 billion cubic metres of concrete are made each year—more than one cubic metre for every person on Earth.[7]

- Woody plants, both true wood from trees and such plants as palms and bamboo, yield natural composites that were used prehistorically by mankind and are still used widely in construction and scaffolding.

- Plywood 3400 BC[8] by the Ancient Mesopotamians; gluing wood at different angles gives better properties than natural wood.

- Cartonnage layers of linen or papyrus soaked in plaster dates to the First Intermediate Period of Egypt c. 2181–2055 BC[8] and was used for death masks.

- Cob mud bricks, or mud walls, (using mud (clay) with straw or gravel as a binder) have been used for thousands of years.

- Concrete was described by Vitruvius, writing around 25 BC in his Ten Books on Architecture, distinguished types of aggregate appropriate for the preparation of lime mortars. For structural mortars, he recommended pozzolana, which were volcanic sands from the sandlike beds of Pozzuoli brownish-yellow-gray in colour near Naples and reddish-brown at Rome. Vitruvius specifies a ratio of 1 part lime to 3 parts pozzolana for cements used in buildings and a 1:2 ratio of lime to pulvis Puteolanus for underwater work, essentially the same ratio mixed today for concrete used at sea.[9] Natural cement-stones, after burning, produced cements used in concretes from post-Roman times into the 20th century, with some properties superior to manufactured Portland cement.

- Papier-mâché, a composite of paper and glue, has been used for hundreds of years.

- The first artificial fibre reinforced plastic was a combination of fiber glass and bakelite, performed in 1935 by Al Simison and Arthur D Little in Owens Corning Company[10]

- One of the most common and familiar composite is fibreglass, in which small glass fibre are embedded within a polymeric material (normally an epoxy or polyester). The glass fibre is relatively strong and stiff (but also brittle), whereas the polymer is ductile (but also weak and flexible). Thus the resulting fibreglass is relatively stiff, strong, flexible, and ductile.

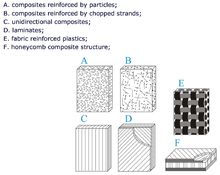

Examples

Composite materials

Concrete is the most common artificial composite material of all and typically consists of loose stones (aggregate) held with a matrix of cement. Concrete is an inexpensive material, and will not compress or shatter even under quite a large compressive force.[11] However, concrete cannot survive tensile loading[12](i.e., if stretched it will quickly break apart). Therefore, to give concrete the ability to resist being stretched, steel bars, which can resist high stretching forces, are often added to concrete to form reinforced concrete.

Fibre-reinforced polymers (FRP)s include carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) and glass-reinforced plastic (GRP). If classified by matrix then there are thermoplastic composites, short fibre thermoplastics, long fibre thermoplastics or long fibre-reinforced thermoplastics. There are numerous thermoset composites, including paper composite panels. Many advanced thermoset polymer matrix systems usually incorporate aramid fibre and carbon fibre in an epoxy resin matrix.

Shape memory polymer composites are high-performance composites, formulated using fibre or fabric reinforcement and shape memory polymer resin as the matrix. Since a shape memory polymer resin is used as the matrix, these composites have the ability to be easily manipulated into various configurations when they are heated above their activation temperatures and will exhibit high strength and stiffness at lower temperatures. They can also be reheated and reshaped repeatedly without losing their material properties. These composites are ideal for applications such as lightweight, rigid, deployable structures; rapid manufacturing; and dynamic reinforcement.

High strain composites are another type of high-performance composites that are designed to perform in a high deformation setting and are often used in deployable systems where structural flexing is advantageous. Although high strain composites exhibit many similarities to shape memory polymers, their performance is generally dependent on the fibre layout as opposed to the resin content of the matrix.

Composites can also use metal fibres reinforcing other metals, as in metal matrix composites (MMC) or ceramic matrix composites (CMC), which includes bone (hydroxyapatite reinforced with collagen fibres), cermet (ceramic and metal) and concrete. Ceramic matrix composites are built primarily for fracture toughness, not for strength. Another class of composite materials involve woven fabric composite consisting of longitudinal and transverse laced yarns. Woven fabric composites are flexible as they are in form of fabric.

Organic matrix/ceramic aggregate composites include asphalt concrete, polymer concrete, mastic asphalt, mastic roller hybrid, dental composite, syntactic foam and mother of pearl. Chobham armour is a special type of composite armour used in military applications.

Additionally, thermoplastic composite materials can be formulated with specific metal powders resulting in materials with a density range from 2 g/cm³ to 11 g/cm³ (same density as lead). The most common name for this type of material is "high gravity compound" (HGC), although "lead replacement" is also used. These materials can be used in place of traditional materials such as aluminium, stainless steel, brass, bronze, copper, lead, and even tungsten in weighting, balancing (for example, modifying the centre of gravity of a tennis racquet), vibration damping, and radiation shielding applications. High density composites are an economically viable option when certain materials are deemed hazardous and are banned (such as lead) or when secondary operations costs (such as machining, finishing, or coating) are a factor.

A sandwich-structured composite is a special class of composite material that is fabricated by attaching two thin but stiff skins to a lightweight but thick core. The core material is normally low strength material, but its higher thickness provides the sandwich composite with high bending stiffness with overall low density.

Wood is a naturally occurring composite comprising cellulose fibres in a lignin and hemicellulose matrix. Engineered wood includes a wide variety of different products such as wood fibre board, plywood, oriented strand board, wood plastic composite (recycled wood fibre in polyethylene matrix), Pykrete (sawdust in ice matrix), Plastic-impregnated or laminated paper or textiles, Arborite, Formica (plastic) and Micarta. Other engineered laminate composites, such as Mallite, use a central core of end grain balsa wood, bonded to surface skins of light alloy or GRP. These generate low-weight, high rigidity materials.

Particulate composites have particle as filler material dispersed in matrix, which may be nonmetal, such as glass, epoxy. Automobile tire is an example of particulate composite.

Advanced diamond-like carbon (DLC) coated polymer composites have been reported[13] where the coating increases the surface hydrophobicity, hardness and wear resistance.

Products

Fibre-reinforced composite materials have gained popularity (despite their generally high cost) in high-performance products that need to be lightweight, yet strong enough to take harsh loading conditions such as aerospace components (tails, wings, fuselages, propellers), boat and scull hulls, bicycle frames and racing car bodies. Other uses include fishing rods, storage tanks, swimming pool panels, and baseball bats. The Boeing 787 and Airbus A350 structures including the wings and fuselage are composed largely of composites. Composite materials are also becoming more common in the realm of orthopedic surgery, and it is the most common hockey stick material.

Carbon composite is a key material in today's launch vehicles and heat shields for the re-entry phase of spacecraft. It is widely used in solar panel substrates, antenna reflectors and yokes of spacecraft. It is also used in payload adapters, inter-stage structures and heat shields of launch vehicles. Furthermore, disk brake systems of airplanes and racing cars are using carbon/carbon material, and the composite material with carbon fibres and silicon carbide matrix has been introduced in luxury vehicles and sports cars.

In 2006, a fibre-reinforced composite pool panel was introduced for in-ground swimming pools, residential as well as commercial, as a non-corrosive alternative to galvanized steel.

In 2007, an all-composite military Humvee was introduced by TPI Composites Inc and Armor Holdings Inc, the first all-composite military vehicle. By using composites the vehicle is lighter, allowing higher payloads. In 2008, carbon fibre and DuPont Kevlar (five times stronger than steel) were combined with enhanced thermoset resins to make military transit cases by ECS Composites creating 30-percent lighter cases with high strength.

Pipes and fittings for various purpose like transportation of potable water, fire-fighting, irrigation, seawater, desalinated water, chemical and industrial waste, and sewage are now manufactured in glass reinforced plastics.

Composite materials used in tensile structures for facade application provides the advantage of being translucent. The woven base cloth combined with the appropriate coating allows better light transmission. This provides a very comfortable level of illumination compared to the full brightness of outside. [14]

The wings of wind turbines, in growing sizes in the order of 50 m length are fabricated in composites since several years.

Two-lower-leg-amputees run on carbon-composite spring-like artificial feet as quick as healthy sportsmen.

High pressure gas cylinders typically about 7–9 litre volume x 300 bar pressure for firemen are nowadays constructed from carbon composite. Type-4-cylinders include metal only as boss that carries the thread to screw in the valve.

On 5 September 2019, HMD Global unveiled the Nokia 6.2 and Nokia 7.2 which are claimed to be using polymer composite for the frames.

Overview

Composites are made up of individual materials referred to as constituent materials. There are two main categories of constituent materials: matrix (binder) and reinforcement. At least one portion of each type is required. The matrix material surrounds and supports the reinforcement materials by maintaining their relative positions. The reinforcements impart their special mechanical and physical properties to enhance the matrix properties. A synergism produces material properties unavailable from the individual constituent materials, while the wide variety of matrix and strengthening materials allows the designer of the product or structure to choose an optimum combination.

Engineered composite materials must be formed to shape. The matrix material can be introduced to the reinforcement before or after the reinforcement material is placed into the mould cavity or onto the mould surface. The matrix material experiences a melding event, after which the part shape is essentially set. Depending upon the nature of the matrix material, this melding event can occur in various ways such as chemical polymerization for a thermoset polymer matrix, or solidification from the melted state for a thermoplastic polymer matrix composite.

A variety of moulding methods can be used according to the end-item design requirements. The principal factors impacting the methodology are the natures of the chosen matrix and reinforcement materials. Another important factor is the gross quantity of material to be produced. Large quantities can be used to justify high capital expenditures for rapid and automated manufacturing technology. Small production quantities are accommodated with lower capital expenditures but higher labour and tooling costs at a correspondingly slower rate.

Many commercially produced composites use a polymer matrix material often called a resin solution. There are many different polymers available depending upon the starting raw ingredients. There are several broad categories, each with numerous variations. The most common are known as polyester, vinyl ester, epoxy, phenolic, polyimide, polyamide, polypropylene, PEEK, and others. The reinforcement materials are often fibres but also commonly ground minerals. The various methods described below have been developed to reduce the resin content of the final product, or the fibre content is increased. As a rule of thumb, lay up results in a product containing 60% resin and 40% fibre, whereas vacuum infusion gives a final product with 40% resin and 60% fibre content. The strength of the product is greatly dependent on this ratio.

Martin Hubbe and Lucian A Lucia consider wood to be a natural composite of cellulose fibres in a matrix of lignin.[15][16]

Constituents

Matrices

Organic

Polymers are common matrices (especially used for fibre reinforced plastics). Road surfaces are often made from asphalt concrete which uses bitumen as a matrix. Mud (wattle and daub) has seen extensive use. Typically, most common polymer-based composite materials, including fibreglass, carbon fibre, and Kevlar, include at least two parts, the substrate and the resin.

Polyester resin tends to have yellowish tint, and is suitable for most backyard projects. Its weaknesses are that it is UV sensitive and can tend to degrade over time, and thus generally is also coated to help preserve it. It is often used in the making of surfboards and for marine applications. Its hardener is a peroxide, often MEKP (methyl ethyl ketone peroxide). When the peroxide is mixed with the resin, it decomposes to generate free radicals, which initiate the curing reaction. Hardeners in these systems are commonly called catalysts, but since they do not re-appear unchanged at the end of the reaction, they do not fit the strictest chemical definition of a catalyst.

Vinyl ester resin tends to have a purplish to bluish to greenish tint. This resin has lower viscosity than polyester resin and is more transparent. This resin is often billed as being fuel resistant, but will melt in contact with gasoline. It tends to be more resistant over time to degradation than polyester resin and is more flexible. It uses the same hardeners as polyester resin (at a similar mix ratio) and the cost is approximately the same.

Epoxy resin is almost transparent when cured. In the aerospace industry, epoxy is used as a structural matrix material or as a structural glue.

Shape memory polymer (SMP) resins have varying visual characteristics depending on their formulation. These resins may be epoxy-based, which can be used for auto body and outdoor equipment repairs; cyanate-ester-based, which are used in space applications; and acrylate-based, which can be used in very cold temperature applications, such as for sensors that indicate whether perishable goods have warmed above a certain maximum temperature. These resins are unique in that their shape can be repeatedly changed by heating above their glass transition temperature (Tg). When heated, they become flexible and elastic, allowing for easy configuration. Once they are cooled, they will maintain their new shape. The resins will return to their original shapes when they are reheated above their Tg. The advantage of shape memory polymer resins is that they can be shaped and reshaped repeatedly without losing their material properties. These resins can be used in fabricating shape memory composites.

Traditional materials such as glues, muds have traditionally been used as matrices for papier-mâché and adobe.

Inorganic

Cement (concrete), metals, ceramics, and sometimes glasses are employed. Unusual matrices such as ice are sometime proposed as in pykecrete.

Reinforcements

Fiber

Reinforcement usually adds rigidity and greatly impedes crack propagation. Thin fibers can have very high strength, and provided they are mechanically well attached to the matrix they can greatly improve the composite's overall properties.

Fibre-reinforced composite materials can be divided into two main categories normally referred to as short fibre-reinforced materials and continuous fiber-reinforced materials. Continuous reinforced materials will often constitute a layered or laminated structure. The woven and continuous fiber styles are typically available in a variety of forms, being pre-impregnated with the given matrix (resin), dry, uni-directional tapes of various widths, plain weave, harness satins, braided, and stitched.

The short and long fibres are typically employed in compression moulding and sheet moulding operations. These come in the form of flakes, chips, and random mate (which can also be made from a continuous fibre laid in random fashion until the desired thickness of the ply / laminate is achieved).

Common fibres used for reinforcement include glass fibres, carbon fibres, cellulose (wood/paper fibre and straw) and high strength polymers for example aramid. Silicon carbide fibers are used for some high temperature applications.

Particle

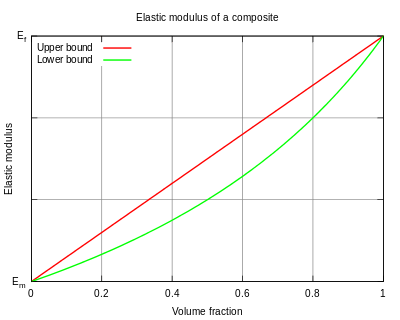

Particle reinforcement adds a similar effect to precipitation hardening in metals and ceramics. Large particles impede dislocation movement and crack propagation as well as contribute to the composite's Young's Modulus. In general, particle reinforcement effect on Young's Modulus lies between values predicted by

as a lower bound and

as an upper bound.

Therefore, it can be expressed as a linear combination of contribution from the matrix and some weighted contribution from the particles.

Where Kc is an experimentally derived constant between 0 and 1. This range of values for Kc reflects that particle reinforced composites are not characterized by the isostrain condition.

Similarly, the tensile strength can be modeled in an equation of similar construction where Ks is a similarly bounded constant not necessarily of the same value of Kc[17]

The true value of Kc and Ks vary based on factors including particle shape, particle distribution, and particle/matrix interface. Knowing these parameters, the mechanical properties can be modeled based on effects from grain boundary strengthening, dislocation strengthening, and Orowan strengthening.[18]

The most common particle reinforced composite is concrete, which is a mixture of gravel and sand usually strengthened by addition of small rocks or sand. Metals are often reinforced with ceramics to increase strength at the cost of ductility. Finally polymers and rubber are often reinforced with carbon black, commonly used in auto tires.[19]

Cores

Many composite layup designs also include a co-curing or post-curing of the prepreg with various other media, such as honeycomb or foam. This is commonly called a sandwich structure. This is a more common layup for the manufacture of radomes, doors, cowlings, or non-structural parts.

Open- and closed-cell-structured foams like polyvinylchloride, polyurethane, polyethylene or polystyrene foams, balsa wood, syntactic foams, and honeycombs are commonly used core materials. Open- and closed-cell metal foam can also be used as core materials. Recently, 3D graphene structures ( also called graphene foam) have also been employed as core structures. A recent review by Khurram and Xu et al., have provided the summary of the state-of-the-art techniques for fabrication of the 3D structure of graphene, and the examples of the use of these foam like structures as a core for their respective polymer composites.[20]

Semi-Crystalline Polymers

Although the two phases are chemically equivalent, semi-crystalline polymers can be described both quantitatively and qualitatively as composite materials. The crystalline portion has a higher elastic modulus and provides reinforcement for the less stiff, amorphous phase. Polymeric materials can range from 0% to 100%[21] crystallinity aka volume fraction depending on molecular structure and thermal history. Different processing techniques can be employed to vary the percent crystallinity in these materials and thus the mechanical properties of these materials as described in the physical properties section. This effect is seen in a variety of places from industrial plastics like polyethylene shopping bags to spiders which can produce silks with different mechanical properties.[22] In many cases these materials act like particle composites with randomly dispersed crystals known as spherulites. However they can also be engineered to be anisotropic and act more like fiber reinforced composites.[23] In the case of spider silk, the properties of the material can even be dependent on the size of the crystals, independent of the volume fraction.[24] Ironically, single component polymeric materials are some of the most easily tunable composite materials known.

Fabrication methods

Fabrication of composite materials is accomplished by a wide variety of techniques, including:

- Advanced fibre placement (Automated fibre placement)

- Tailored fibre placement

- fibreglass spray lay-up process

- Filament winding

- Lanxide process

- Tufting

- Z-pinning

Composite fabrication usually involves wetting, mixing or saturating the reinforcement with the matrix, and then causing the matrix to bind together (with heat or a chemical reaction) into a rigid structure. The operation is usually done in an open or closed forming mould, but the order and ways of introducing the ingredients varies considerably.

Mould overview

Within a mould, the reinforcing and matrix materials are combined, compacted, and cured (processed) to undergo a melding event. After the melding event, the part shape is essentially set, although it can deform under certain process conditions. For a thermoset polymer matrix material, the melding event is a curing reaction that is initiated by the application of additional heat or chemical reactivity such as an organic peroxide. For a thermoplastic polymeric matrix material, the melding event is a solidification from the melted state. For a metal matrix material such as titanium foil, the melding event is a fusing at high pressure and a temperature near the melting point.

For many moulding methods, it is convenient to refer to one mould piece as a "lower" mould and another mould piece as an "upper" mould. Lower and upper refer to the different faces of the moulded panel, not the mould's configuration in space. In this convention, there is always a lower mould, and sometimes an upper mould. Part construction begins by applying materials to the lower mould. Lower mould and upper mould are more generalized descriptors than more common and specific terms such as male side, female side, a-side, b-side, tool side, bowl, hat, mandrel, etc. Continuous manufacturing uses a different nomenclature.

The moulded product is often referred to as a panel. For certain geometries and material combinations, it can be referred to as a casting. For certain continuous processes, it can be referred to as a profile.

Vacuum bag moulding

Vacuum bag moulding uses a flexible film to enclose the part and seal it from outside air. Vacuum bag material is available in a tube shape or a sheet of material. A vacuum is then drawn on the vacuum bag and atmospheric pressure compresses the part during the cure. When a tube shaped bag is used, the entire part can be enclosed within the bag. When using sheet bagging materials, the edges of the vacuum bag are sealed against the edges of the mould surface to enclose the part against an air-tight mould. When bagged in this way, the lower mold is a rigid structure and the upper surface of the part is formed by the flexible membrane vacuum bag. The flexible membrane can be a reusable silicone material or an extruded polymer film. After sealing the part inside the vacuum bag, a vacuum is drawn on the part (and held) during cure. This process can be performed at either ambient or elevated temperature with ambient atmospheric pressure acting upon the vacuum bag. A vacuum pump is typically used to draw a vacuum. An economical method of drawing a vacuum is with a venturi vacuum and air compressor.

A vacuum bag is a bag made of strong rubber-coated fabric or a polymer film used to compress the part during cure or hardening. In some applications the bag encloses the entire material, or in other applications a mold is used to form one face of the laminate with the bag being a single layer to seal to the outer edge of the mold face. When using a tube shaped bag, the ends of the bag are sealed and the air is drawn out of the bag through a nipple using a vacuum pump. As a result, uniform pressure approaching one atmosphere is applied to the surfaces of the object inside the bag, holding parts together while the adhesive cures. The entire bag may be placed in a temperature-controlled oven, oil bath or water bath and gently heated to accelerate curing.

Vacuum bagging is widely used in the composites industry as well.[25] Carbon fibre fabric and fibreglass, along with resins and epoxies are common materials laminated together with a vacuum bag operation.

- Woodworking applications

In commercial woodworking facilities, vacuum bags are used to laminate curved and irregular shaped workpieces.

Typically, polyurethane or vinyl materials are used to make the bag. A tube shaped bag is open at both ends. The piece, or pieces to be glued are placed into the bag and the ends sealed. One method of sealing the open ends of the bag is by placing a clamp on each end of the bag. A plastic rod is laid across the end of the bag, the bag is then folded over the rod. A plastic sleeve with an opening in it, is then snapped over the rod. This procedure forms a seal at both ends of the bag, when the vacuum is ready to be drawn.

A "platen" is sometimes used inside the bag for the piece being glued to lie on. The platen has a series of small slots cut into it, to allow the air under it to be evacuated. The platen must have rounded edges and corners to prevent the vacuum from tearing the bag.

When a curved part is to be glued in a vacuum bag, it is important that the pieces being glued be placed over a solidly built form, or have an air bladder placed under the form. This air bladder has access to "free air" outside the bag. It is used to create an equal pressure under the form, preventing it from being crushed.[26]

Pressure bag moulding

This process is related to vacuum bag molding in exactly the same way as it sounds. A solid female mold is used along with a flexible male mold. The reinforcement is placed inside the female mold with just enough resin to allow the fabric to stick in place (wet lay up). A measured amount of resin is then liberally brushed indiscriminately into the mold and the mold is then clamped to a machine that contains the male flexible mold. The flexible male membrane is then inflated with heated compressed air or possibly steam. The female mold can also be heated. Excess resin is forced out along with trapped air. This process is extensively used in the production of composite helmets due to the lower cost of unskilled labor. Cycle times for a helmet bag moulding machine vary from 20 to 45 minutes, but the finished shells require no further curing if the molds are heated.

Autoclave moulding

A process using a two-sided mould set that forms both surfaces of the panel. On the lower side is a rigid mould and on the upper side is a flexible membrane made from silicone or an extruded polymer film such as nylon. Reinforcement materials can be placed manually or robotically. They include continuous fibre forms fashioned into textile constructions. Most often, they are pre-impregnated with the resin in the form of prepreg fabrics or unidirectional tapes. In some instances, a resin film is placed upon the lower mould and dry reinforcement is placed above. The upper mould is installed and vacuum is applied to the mould cavity. The assembly is placed into an autoclave. This process is generally performed at both elevated pressure and elevated temperature. The use of elevated pressure facilitates a high fibre volume fraction and low void content for maximum structural efficiency.

Resin transfer moulding (RTM)

RTM is a process using a rigid two-sided mould set that forms both surfaces of the panel. The mould is typically constructed from aluminum or steel, but composite molds are sometimes used. The two sides fit together to produce a mould cavity. The distinguishing feature of resin transfer moulding is that the reinforcement materials are placed into this cavity and the mould set is closed prior to the introduction of matrix material. Resin transfer moulding includes numerous varieties which differ in the mechanics of how the resin is introduced to the reinforcement in the mould cavity. These variations include everything from the RTM methods used in out of autoclave composite manufacturing for high-tech aerospace components to vacuum infusion (for resin infusion see also boat building) to vacuum assisted resin transfer moulding (VARTM). This process can be performed at either ambient or elevated temperature and is suitable for manufacturing high performance composite components in medium volumes (1,000s to 10,000s of parts).[27]

Light Resin Transfer Molding (LRTM)

Similar to the methods performed in Resin Transfer Molding, Light Resin Transfer Molding (Light RTM) involves a closed mold process. A vacuum holds mold A and mold B together to result in two finished sides with fixed thickness levels. Vacuum rings around the tools hold the molds together for this process after dry fiber reinforcements are loaded into mold A before joining with mold B. The air is vacuumed out of the molds with a lower vacuum level, separate from the tooling. After the air is removed the resin is injected into the part. The vacuum remains in effect into the resin is cured.[28]

Other fabrication methods

Other types of fabrication include press moulding, transfer moulding, pultrusion moulding, filament winding, casting, centrifugal casting, braiding (onto a former), continuous casting and slip forming. There are also forming capabilities including CNC filament winding, vacuum infusion, wet lay-up, compression moulding, and thermoplastic moulding, to name a few. The use of curing ovens and paint booths is also needed for some projects.

Finishing methods

The finishing of the composite parts is also critical in the final design. Many of these finishes will include rain-erosion coatings or polyurethane coatings.

Tooling

The mould and mould inserts are referred to as "tooling." The mould/tooling can be constructed from a variety of materials. Tooling materials include invar, steel, aluminium, reinforced silicone rubber, nickel, and carbon fibre. Selection of the tooling material is typically based on, but not limited to, the coefficient of thermal expansion, expected number of cycles, end item tolerance, desired or required surface condition, method of cure, glass transition temperature of the material being moulded, moulding method, matrix, cost and a variety of other considerations.

Physical properties

The physical properties of composite materials are generally not isotropic (independent of direction of applied force) in nature, but they are typically anisotropic (different depending on the direction of the applied force or load). For instance, the stiffness of a composite panel will often depend upon the orientation of the applied forces and/or moments. The strength of a composite is bounded by two loading conditions as shown in the plot to the right.

Isostrain rule of mixtures

If both the fibres and matrix are aligned parallel to the loading direction, the deformation of both phases will be the same (assuming there is no delamination at the fibre-matrix interface). This isostrain condition provides the upper bound for composite strength, and is determined by the rule of mixtures:

where EC is the effective composite Young's modulus, and Vi and Ei are the volume fraction and Young's moduli, respectively, of the composite phases.

For example, a composite material made up of α and β phases as shown in the figure to the right under isostrain, the Young's modulus would be as follows:

where Vα and Vβ are the respective volume fractions of each phase. This can be derived by considering that in the isostrain case,

Assuming that the composite has a uniform cross section, the stress on the composite is a weighted average between the two phases,

The stresses in the individual phases are given by Hooke's Law,

Combining these equations gives that the overall stress in the composite is

Now we can show

Isostress rule of mixtures

The lower bound is dictated by the isostress condition, in which the fibres and matrix are oriented perpendicularly to the loading direction:

and now the strains become a weighted average

Rewriting Hooke's Law for the individual phases

This leads to

From the definition of Hooke's Law

and in general

Following the example above, if one had a composite material made up of α and β phases under isostress conditions as shown in the figure to the right, the composition Young's modulus would be:

The isostrain condition implies that under an applied load, both phases experience the same strain but will feel different stress. Comparatively, under isostress conditions both phases will feel the same stress but the strains will differ between each phase.

A generalized equation for any loading condition between isostrain and isostress can be written as[30]:

where X is a material property such as modulus or stress, c, m, and r stand for the properties of the composite, matrix, and reinforcement materials respectively, and n is a value between 1 and -1.

The above equation can be further generalized beyond a two phase composite to an m-component system:

Though composite stiffness is maximized when fibres are aligned with the loading direction, so is the possibility of fibre tensile fracture, assuming the tensile strength exceeds that of the matrix. When a fibre has some angle of misorientation θ, several fracture modes are possible. For small values of θ the stress required to initiate fracture is increased by a factor of (cos θ)−2 due to the increased cross-sectional area (A cos θ) of the fibre and reduced force (F/cos θ) experienced by the fibre, leading to a composite tensile strength of σparallel /cos2 θ where σparallel is the tensile strength of the composite with fibres aligned parallel with the applied force.

Intermediate angles of misorientation θ lead to matrix shear failure. Again the cross sectional area is modified but since shear stress is now the driving force for failure the area of the matrix parallel to the fibres is of interest, increasing by a factor of 1/sin θ. Similarly, the force parallel to this area again decreases (F/cos θ) leading to a total tensile strength of τmy /sinθ cosθ where τmy is the matrix shear strength.

Finally, for large values of θ (near π/2) transverse matrix failure is the most likely to occur, since the fibres no longer carry the majority of the load. Still, the tensile strength will be greater than for the purely perpendicular orientation, since the force perpendicular to the fibres will decrease by a factor of 1/sin θ and the area decreases by a factor of 1/sin θ producing a composite tensile strength of σperp /sin2θ where σperp is the tensile strength of the composite with fibres align perpendicular to the applied force.[31]

The majority of commercial composites are formed with random dispersion and orientation of the strengthening fibres, in which case the composite Young's modulus will fall between the isostrain and isostress bounds. However, in applications where the strength-to-weight ratio is engineered to be as high as possible (such as in the aerospace industry), fibre alignment may be tightly controlled.

Panel stiffness is also dependent on the design of the panel. For instance, the fibre reinforcement and matrix used, the method of panel build, thermoset versus thermoplastic, and type of weave.

In contrast to composites, isotropic materials (for example, aluminium or steel), in standard wrought forms, typically have the same stiffness regardless of the directional orientation of the applied forces and/or moments. The relationship between forces/moments and strains/curvatures for an isotropic material can be described with the following material properties: Young's Modulus, the shear Modulus and the Poisson's ratio, in relatively simple mathematical relationships. For the anisotropic material, it requires the mathematics of a second order tensor and up to 21 material property constants. For the special case of orthogonal isotropy, there are three different material property constants for each of Young's Modulus, Shear Modulus and Poisson's ratio—a total of 9 constants to describe the relationship between forces/moments and strains/curvatures.

Techniques that take advantage of the anisotropic properties of the materials include mortise and tenon joints (in natural composites such as wood) and Pi Joints in synthetic composites.

Mechanical Properties of Composites

Particle Reinforcement

In general, particle reinforcement is strengthening the composites less than fiber reinforcement. It is used to enhance the stiffness of the composites while increasing the strength and the toughness. Because of their mechanical properties, they are used in applications in which wear resistance is required. For example, hardness of cement can be increased by reinforcing gravel particles, drastically. Particle reinforcement a highly advantageous method of tuning mechanical properties of materials since it is very easy implement while being low cost [32][33][34].

The elastic modulus of particle-reinforced composites can be expressed as,

where E is the elastic modulus, V is the volume fraction. The subscripts c, p and m are indicating composite, particle and matrix, respectively. is a constant can be found empirically.

Similarly, tensile strength of particle-reinforced composites can be expressed as,

where T.S. is the tensile strength, and is a constant (not equal to ) that can be found empirically.

Continuous Fiber Reinforcement

In general, continuous fiber reinforcement is implemented by incorporating a fiber as the strong phase into a weak phase, matrix. The reason for the popularity of fiber usage is materials with extraordinary strength can be obtained in their fiber form. Non-metallic fibers are usually showing a very high strength to density ratio compared to metal fibers because of the covalent nature of their bonds [35]. The most famous example of this is carbon fibers that have many applications extending from sports gear to protective equipment to space industries[36][37].

The stress on the composite can be expressed in terms of the volume fraction of the fiber and the matrix.

where is the stress, V is the volume fraction. The subscripts c, f and m are indicating composite, fiber and matrix, respectively.

Although the stress-strain behavior of fiber composites can only be determined by testing, there is an expected trend, three stages of the stress-strain curve. The first stage is the region of the stress-strain curve where both fiber and the matrix are elastically deformed. This linearly elastic region can be expressed in the following form[36].

where is the stress, is the strain, E is the elastic modulus, and V is the volume fraction. The subscripts c, f, and m are indicating composite, fiber, and matrix, respectively.

After passing the elastic region for both fiber and the matrix, the second region of the stress-strain curve can be observed. In the second region, the fiber is still elastically deformed while the matrix is plastically deformed since the matrix is the weak phase. The instantaneous modulus can be determined using the slope of the stress-strain curve in the second region. The relationship between stress and strain can be expressed as,

where is the stress, is the strain, E is the elastic modulus, and V is the volume fraction. The subscripts c, f, and m are indicating composite, fiber, and matrix, respectively. To find the modulus in the second region derivative of this equation can be used since the slope of the curve is equal to the modulus.

In most cases we can assume since the second term is much less than the first one[36].

In reality, the derivative of stress with respect to strain is not always returning the modulus because of the binding interaction between the fiber and matrix. The strength of the interaction between these two phases can result in changes in the mechanical properties of the composite. The compatibility of the fiber and matrix is a measure of internal stress[36].

The covalently bonded high strength fibers (e.g. carbon fibers) experience mostly elastic deformation before the fracture since the plastic deformation can happen due to dislocation motion. Whereas, metallic fibers have more space to plastically deform, so their composites exhibit a third stage where both fiber and the matrix are plastically deforming. Metallic fibers have many applications to work at cryogenic temperatures that is one of the advantages of composites with metal fibers over nonmetallic. The stress in this region of the stress-strain curve can be expressed as,

where is the stress, is the strain, E is the elastic modulus, and V is the volume fraction. The subscripts c, f, and m are indicating composite, fiber, and matrix, respectively. and are for fiber and matrix flow stresses respectively. Just after the third region the composite exhibit necking. The necking strain of composite is happened to be between the necking strain of the fiber and the matrix just like other mechanical properties of the composites. The necking strain of the weak phase is delayed by the strong phase. The amount of the delay depends upon the volume fraction of the strong phase[36].

Thus, the tensile strength of the composite can be expressed in terms of the volume fraction[36].

where T.S. is the tensile strength, is the stress, is the strain, E is the elastic modulus, and V is the volume fraction. The subscripts c, f, and m are indicating composite, fiber, and matrix, respectively. The composite tensile strength can be expressed as

for is less than or equal to (arbitrary critical value of volume fraction)

for is greater than or equal to

The critical value of volume fraction can be expressed as,

Evidently, the composite tensile strength can be higher than the matrix if is greater than .

Thus, the minimum volume fraction of the fiber can be expressed as,

Although this minimum value is very low in practice, it is very important to know since the reason for the incorporation of continuous fibers is to improve the mechanical properties of the materials/composites, and this value of volume fraction is the threshold of this improvement[36].

The Effect of Fiber Orientation

The change is in the fiber orientation can affect the mechanical properties of the fiber-reinforced composites especially the tensile strength.

The composite tensile strength can be predicted to depending on the (0° to 10° angles), the angle between the applied for, and the orientation of the fibers[36].

where T.S. is the tensile strength, is the parallel stress.

Because of the misorientation, the matrix of the composite experiences a shear force. The tensile strength of composites (10° - 60° angles) due to shear failure of the matrix can be expressed as,

where T.S. is the tensile strength, is the shear stress[36].

If the angle is even greater than (60° - 90° angles), another mode of failure, transverse mode, becomes effective. The composite transverse fracture strength can be expressed as,

where T.S. is the tensile strength, is the perpendicular stress[36].

Thus, the angle at which the transition to fracture mode can be expressed as,

where is the critical angle, is the parallel stress, and is the shear stress[36].

This critical angle is important for the design of the composite materials for certain applications.

Types of Fibers and Their Mechanical Properties

The most common types of fibers used in industry are glass fibers, carbon fibers, and kevlar due to their ease of production and availability. Their mechanical properties are very important to know, therefore the table of their mechanical properties is given below to compare them with S97 steel [38][39][40][41]. The angle of fiber orientation is very important because of the anisotropy of fiber composites (please see the section "Physical Properties" for a more detailed explanation). The mechanical properties of the composites can be tested using standard mechanical testing methods by positioning the samples at various angles (the standard angles are 0°, 45°, and 90°) with respect to the orientation of fibers within the composites. In general, 0° axial alignment makes composites resistant to longitudinal bending and axial tension/compression, 90° hoop alignment is used to obtain resistance to internal/external pressure, and ± 45° is the ideal choice to obtain resistance against pure torsion[42].

Mechanical Properties of Fiber Composite Materials

| Symbol | Units | Standard

Carbon Fiber Fabric |

High Modulus

Carbon Fiber Fabric |

E-Glass

Fibre Glass Fabric |

Kevlar

Fabric |

Standard

Unidirectional Carbon Fiber Fabric |

High Modulus

Unidirectional Carbon Fiber Fabric |

E-Glass

Unidirectional Fiber Glass Fabric |

Kevlar

Unidirectional Fabric |

Steel

S97 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young’s Modulus 0° | E1 | GPa | 70 | 85 | 25 | 30 | 135 | 175 | 40 | 75 | 207 |

| Young’s Modulus 90° | E2 | GPa | 70 | 85 | 25 | 30 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 207 |

| In-plane Shear Modulus | G12 | GPa | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 80 |

| Major Poisson’s Ratio | v12 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.34 | - | |

| Ult. Tensile Strength 0° | Xt | MPa | 600 | 350 | 440 | 480 | 1500 | 1000 | 1000 | 1300 | 990 |

| Ult. Comp. Strength 0° | Xc | MPa | 570 | 150 | 425 | 190 | 1200 | 850 | 600 | 280 | - |

| Ult. Tensile Strength 90° | Yt | MPa | 600 | 350 | 440 | 480 | 50 | 40 | 30 | 30 | - |

| Ult. Comp. Strength 90° | Yc | MPa | 570 | 150 | 425 | 190 | 250 | 200 | 110 | 140 | - |

| Ult. In-plane Shear Stren. | S | MPa | 90 | 35 | 40 | 50 | 70 | 60 | 40 | 60 | - |

| Ult. Tensile Strain 0° | ext | % | 0.85 | 0.40 | 1.75 | 1.60 | 1.05 | 0.55 | 2.50 | 1.70 | - |

| Ult. Comp. Strain 0° | exc | % | 0.80 | 0.15 | 1.70 | 0.60 | 0.85 | 0.45 | 1.50 | 0.35 | - |

| Ult. Tensile Strain 90° | eyt | % | 0.85 | 0.40 | 1.75 | 1.60 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.35 | 0.50 | - |

| Ult. Comp. Strain 90° | eyc | % | 0.80 | 0.15 | 1.70 | 0.60 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 1.35 | 2.30 | - |

| Ult. In-plane shear strain | es | % | 1.80 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.40 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 3.00 | - |

| Density | g/cc | 1.60 | 1.60 | 1.90 | 1.40 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 1.90 | 1.40 | - |

| Symbol | Units | Standard

Carbon Fiber |

High Modulus

Carbon Fiber |

E-Glass

Fiber Glass |

Standard

Carbon Fibers Fabric |

E-Glass

Fiber Glass Fabric |

Steel | Al | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Modulus | E1 | GPa | 17 | 17 | 12.3 | 19.1 | 12.2 | 207 | 72 |

| Transverse Modulus | E2 | GPa | 17 | 17 | 12.3 | 19.1 | 12.2 | 207 | 72 |

| In Plane Shear Modulus | G12 | GPa | 33 | 47 | 11 | 30 | 8 | 80 | 25 |

| Poisson’s Ratio | v12 | .77 | .83 | .53 | .74 | .53 | |||

| Tensile Strength | Xt | MPa | 110 | 110 | 90 | 120 | 120 | 990 | 460 |

| Compressive Strength | Xc | MPa | 110 | 110 | 90 | 120 | 120 | 990 | 460 |

| In Plane Shear Strength | S | MPa | 260 | 210 | 100 | 310 | 150 | ||

| Thermal Expansion Co-ef | Alpha1 | Strain/K | 2.15 E-6 | 0.9 E-6 | 12 E-6 | 4.9 E-6 | 10 E-6 | 11 E-6 | 23 E-6 |

| Moisture Co-ef | Beta1 | Strain/K | 3.22 E-4 | 2.49 E-4 | 6.9 E-4 |

Mechanical Properties of Aerospace Grade & Commercial Grade Carbon Fiber Composites, Fiberglass Composite, and Aluminum Alloy and Steel

This table is demonstrating one of the most important features and advantage of fiber composites over metal, that is specific strength and specific stiffness. Although the steel and the aluminum alloy have comparable strength and stiffness with fiber composites, the specific strength and stiffness of composites are around 9 - 10 times higher than steel and the aluminum alloy[35].

| Carbon Fiber Composite (aerospace grade) | Carbon Fiber Composite (commercial grade) | Fiberglass Composite | Aluminum 6061 T-6 | Steel,

Mild | |

| Cost $/LB | $20 - $250+ | $5 - $20 | $1.50 - $3.00 | $3 | $0.30 |

| Strength (psi) | 90,000 - 200,000 | 50,000 - 90,000 | 20,000 - 35,000 | 35,000 | 60,000 |

| Stiffness (psi) | 10 x 106- 50 x 106 | 8 x 106 - 10 x 106 | 1 x 106 - 1.5 x 106 | 10 x 106 | 30 x 106 |

| Density (lb/in3) | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.055 | 0.10 | 0.30 |

| Specific Strength | 1.8 x 106 - 4 x 106 | 1 x 106 - 1.8 x | 363,640-636,360 | 350,000 | 200,000 |

| Specific Stiffness | 200 x 106 - 1,000 x 106 | 160 x 106-200 x 106 | 18 x 106-27 x 106 | 100 x 106 | 100 x 106 |

Failure

Shock, impact, or repeated cyclic stresses can cause the laminate to separate at the interface between two layers, a condition known as delamination. Individual fibres can separate from the matrix e.g. fibre pull-out.

Composites can fail on the microscopic or macroscopic scale. Compression failures can occur at both the macro scale or at each individual reinforcing fibre in compression buckling. Tension failures can be net section failures of the part or degradation of the composite at a microscopic scale where one or more of the layers in the composite fail in tension of the matrix or failure of the bond between the matrix and fibres.

Some composites are brittle and have little reserve strength beyond the initial onset of failure while others may have large deformations and have reserve energy absorbing capacity past the onset of damage. The variations in fibres and matrices that are available and the mixtures that can be made with blends leave a very broad range of properties that can be designed into a composite structure. The best known failure of a brittle ceramic matrix composite occurred when the carbon-carbon composite tile on the leading edge of the wing of the Space Shuttle Columbia fractured when impacted during take-off. It led to catastrophic break-up of the vehicle when it re-entered the Earth's atmosphere on 1 February 2003.

Compared to metals, composites have relatively poor bearing strength.

Testing

To aid in predicting and preventing failures, composites are tested before and after construction. Pre-construction testing may use finite element analysis (FEA) for ply-by-ply analysis of curved surfaces and predicting wrinkling, crimping and dimpling of composites.[45][46][47][48] Materials may be tested during manufacturing and after construction through several nondestructive methods including ultrasonics, thermography, shearography and X-ray radiography,[49] and laser bond inspection for NDT of relative bond strength integrity in a localized area.

See also

- Aluminium composite panel

- American Composites Manufacturers Association

- Chemical vapour infiltration

- Composite (disambiguation)

- Composite laminates

- Epoxy granite

- Hybrid material

- Nanocomposites

- Rule of mixtures

- Scaled Composites, American aerospace company founded by Burt Rutan

- Void (composites)

References

- Fazeli, Mahyar; Florez, Jennifer Paola; Simão, Renata Antoun (April 2019). "Improvement in adhesion of cellulose fibers to the thermoplastic starch matrix by plasma treatment modification". Composites Part B: Engineering. 163: 207–216. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.11.048.

- Elhajjar, Rani; La Saponara, Valeria; Muliana, Anastasia, eds. (2017). Smart Composites: Mechanics and Design (Composite Materials). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-138-07551-1.

- McEvoy, M. A.; Correll, N. (19 March 2015). "Materials that couple sensing, actuation, computation, and communication". Science. 347 (6228): 1261689. doi:10.1126/science.1261689. PMID 25792332.

- "Autonomous Materials Will Let Future Robots Change Color And Shift Shape". popsci.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Fazeli, Mahyar; Keley, Meysam; Biazar, Esmaeil (September 2018). "Preparation and characterization of starch-based composite films reinforced by cellulose nanofibers". International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 116: 272–280. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.04.186. PMID 29729338.

- Shaffer, Gary D. (Spring 1993). "An Archaeomagnetic Study of a Wattle and Daub Building Collapse". Journal of Field Archaeology. 20 (1): 59–75. JSTOR 530354.

- "Minerals commodity summary – cement – 2007". US United States Geological Survey. 1 June 2007. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- "History of Composite Materials". Mar-Bal Incorporated. 2013-08-19. Archived from the original on 2018-01-04. Retrieved 2018-01-03.

- Heather Lechtman and Linn Hobbs "Roman Concrete and the Roman Architectural Revolution", Ceramics and Civilization Volume 3: High Technology Ceramics: Past, Present, Future, edited by W.D. Kingery and published by the American Ceramics Society, 1986; and Vitruvius, Book II:v,1; Book V:xii2

- Owens corning milestones 2017

- "Slabs On Grade". Construction Knowldegs.net. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- "Behaviour of Concrete Under Tension". The Constructor. 2012-12-06. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- Zia, Abdul Wasy; Shah, Atta Ur Rehman; Lee, Seunghun; Song, Jung Il (2015). "Development of diamond-like-carbon coated abaca-reinforced polyester composites for hydrophobic and outdoor structural applications". Polymer Bulletin. 72 (11): 2797–2808. doi:10.1007/s00289-015-1436-y. ISSN 0170-0839.

- "The pros and cons of fabric structures | Span Design".

- Hubbe, Martin A.; Lucia, Lucian A. "The "love-hate" relationship present in lignocellulosic materials" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-03-27. Retrieved 2009-12-25.

- David Hon and Nobuo Shiraishi, eds. (2001) Wood and cellulose chemistry, 2nd ed. (New York: Marcel Dekker), p. 5 ff.

- H., Courtney, Thomas (2000). Mechanical behavior of materials (2nd ed.). Boston: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0070285941. OCLC 41932585.

- Wu, Guoqing; Zhang, Qingqing; Yang, Xue; Huang, Zheng; Sha, Wei (24 December 2013). "Effects of particle/matrix interface and strengthening mechanisms on the mechanical properties of metal matrix composites". Composite Interfaces. 21 (5): 415–429. doi:10.1080/15685543.2014.872914.

- "Chapter 17. Composites". www.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2018-05-19.

- Shehzad, Khurram; Xu, Yang; Gao, Chao; Duan, Xiangfeng (2016). "Three-dimensional macro-structures of two-dimensional nanomaterials". Chemical Society Reviews. 45 (20): 5541–5588. doi:10.1039/c6cs00218h. PMID 27459895.

- Agbolaghi, Samira, Saleheh Abbaspoor, and Farhang Abbasi. "A Comprehensive Review on Polymer Single Crystals—From Fundamental Concepts to Applications." Progress in Polymer Science 81 (2018): 22-79. Web.

- Termonia, Yves (December 1994). "Molecular Modeling of Spider Silk Elasticity". Macromolecules. 27 (25): 7378–7381. Bibcode:1994MaMol..27.7378T. doi:10.1021/ma00103a018.

- Quan, Hui; Li, Zhong-Ming; Yang, Ming-Bo; Huang, Rui (June 2005). "On transcrystallinity in semi-crystalline polymer composites". Composites Science and Technology. 65 (7–8): 999–1021. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2004.11.015.

- Keten, Sinan; Xu, Zhiping; Ihle, Britni; Buehler, Markus J. (14 March 2010). "Nanoconfinement controls stiffness, strength and mechanical toughness of β-sheet crystals in silk". Nature Materials. 9 (4): 359–367. Bibcode:2010NatMa...9..359K. doi:10.1038/nmat2704. PMID 20228820.

- "What is Vacuum Bagging?". Coventive Composites. 2018-09-20. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- "Vacuum Bags For Woodworking". Archived from the original on 2010-09-28.

- "What is Resin Transfer Moulding (RTM)?". Coventive Composites. 2018-04-25. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- "Composite Epoxy Resin Manufacturing - Copps Industries". Copps Industries. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- Kim, Hyoung Seop (September 2000). "On the rule of mixtures for the hardness of particle reinforced composites". Materials Science and Engineering: A. 289 (1–2): 30–33. doi:10.1016/S0921-5093(00)00909-6.

- Soboyejo, W. O. (2003). "9.3.1 Constant-Strain and Constant-Stress Rules of Mixtures". Mechanical properties of engineered materials. Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-8900-8. OCLC 300921090.

- Courtney, Thomas H. (2000). Mechanical Behavior of Materials (2nd ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc. pp. 263–265. ISBN 978-1-57766-425-3.

- Wu, Xiangguo; Yang, Jing; Mpalla, Issa B. (2013-12-25). "Preliminary design and structural responses of typical hybrid wind tower made of ultra high performance cementitious composites". Structural Engineering and Mechanics. 48 (6): 791–807. doi:10.12989/sem.2013.48.6.791. ISSN 1225-4568.

- Li, Mo; Li, Victor C. (2012-07-25). "Rheology, fiber dispersion, and robust properties of Engineered Cementitious Composites". Materials and Structures. 46 (3): 405–420. doi:10.1617/s11527-012-9909-z. hdl:2027.42/94214. ISSN 1359-5997.

- "Large-Scale Processing of Engineered Cementitious Composites". ACI Materials Journal. 105 (4). 2008. doi:10.14359/19897. ISSN 0889-325X.

- "Fiber-Reinforced Composite - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- Courtney, Thomas H. (2005-12-16). Mechanical Behavior of Materials: Second Edition. Waveland Press. ISBN 978-1-4786-0838-7.

- Park, Soo-Jin, auteur. Carbon Fibers. ISBN 978-94-017-9478-7. OCLC 914220273.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Carbon Fibre, Tubes, Profiles - Filament Winding and Composite Engineering". www.performance-composites.com. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- "Composite Manufacturing | Performance Composites". www.performancecomposites.com. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- "Composite Materials • Innovative Composite Engineering". Innovative Composite Engineering. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- "Reinforcement Fabrics - In Stock for Same Day Shipping | Fibre Glast". www.fibreglast.com. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- "Filament Winding, Carbon Fibre Angles in Composite Tubes". www.performance-composites.com. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- "Mechanical Properties of Carbon Fibre Composite Materials". www.performance-composites.com. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- "Carbon Fiber Composite Design Guide" (PDF). www.performancecomposites.com. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- Waterman, Pamela J. "The Life of Composite Materials". Desktop Engineering Magazine. April 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-12-02.

- Aghdam, M.M.; Morsali, S.R. (November 2013). "Damage initiation and collapse behavior of unidirectional metal matrix composites at elevated temperatures". Computational Materials Science. 79: 402–407. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2013.06.024.

- Kishore., Debnath (2017-09-18). Primary and Secondary Manufacturing of Polymer Matrix Composites. Singh, Inderdeep. [Place of publication not identified]. ISBN 9781498799300. OCLC 1004424029.

- What is Finite Element Analysis?

- Matzkanin, George A.; Yolken, H. Thomas. "Techniques for the Nondestructive Evaluation of Polymer Matrix Composites" (PDF). AMMTIAC Quarterly. 2 (4). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17.

Further reading

- Robert M. Jones (1999). Mechanics of Composite Materials (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781560327127.

- Polymers and Polymeric Composites: A Reference Series. Springer. 1999.

- Autar K. Kaw (2005). Mechanics of Composite Materials (2nd ed.). CRC. ISBN 978-0-8493-1343-1.

- Handbook of Polymer Composites for Engineers By Leonard Hollaway Published 1994 Woodhead Publishing

- Madbouly, Samy, Chaoqun Zhang, and Michael R. Kessler. Bio-Based Plant Oil Polymers and Composites. William Andrew, 2015.

- Matthews, F.L.; Rawlings, R.D. (1999). Composite Materials: Engineering and Science. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0621-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Composite materials. |

Smart materialSmart Materials and Structures

- Distance learning course in polymers and composites

- High Density Composites Replace Lead

- Strength of Composites

- Composite Sandwich Structure of Minardi F1 Car

- OptiDAT composite material database

- Tests originally developed to test metals have been adapted by the industry to test composites

- World leading centre for advanced composites

- Almudaihesh, Faisel; Holford, Karen; Pullin, Rhys; Eaton, Mark (2020-02-01). "The influence of water absorption on unidirectional and 2D woven CFRP composites and their mechanical performance". Composites Part B: Engineering. 182: 107626. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107626. ISSN 1359-8368.