American logistics in the Normandy campaign

American logistics in the Normandy campaign played a key role in the success of Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of northwest Europe during World War II that commenced on D-Day, 6 June 1944. The Services of Supply (SOS) was formed in May 1942 under the command of Major General John C. H. Lee to provide logistical support. From February 1944 on, SOS was increasingly referred to as the Communications Zone (COMZ). Between May 1942 and May 1944, Operation Bolero, the buildup of American troops and supplies in the UK, proceeded fitfully, and by June 1944 1,526,965 US troops were in the UK, of whom 459,511 were part of the COMZ.

The First United States Army was supported over the Omaha and Utah Beaches, and through the Mulberry artificial port specially constructed for the purpose, but the American Mulberry was abandoned after it was damaged by a storm on 19 June. During the first seven weeks after D-Day, the advance was much slower than the Operation Overlord plan had anticipated, and the lodgment area much smaller. The nature of the fighting in the Normandy hedgerows created shortages of certain items, particularly artillery and mortar ammunition, and there was unexpectedly high rates of loss of bazookas, Browning automatic rifles (BARs), and M7 grenade launchers.

On 25 July, the First Army began Operation Cobra, the break-out from Normandy. The advance was much faster than expected and the rapid increase in the length of the line of communications threw up unanticipated logistical challenges. The logistical plan lacked the flexibility needed to cope with the rapidly changing operational situation, and the rehabilitation of railways and construction of pipelines could not keep up with the pace of the advance. Major shortages developed, particularly of petrol, oil and lubricants (POL). Motor transport was used as a stopgap, and the Advance Section (ADSEC) organized the Red Ball Express, which delivered supplies from the Normandy lodgment area, but at great cost in wear and tear, and accidental damage.

Senior commanders subordinated logistical imperatives to operational opportunities. Two decisions in particular had long-term and far-reaching effects. The decision to abandon plans to develop the ports of Brittany left the American forces with only the port of Cherbourg and the Normandy beaches for their maintenance. The subsequent decision to continue the pursuit beyond the Seine led to the attrition of equipment, failure to establish a proper supply depot system, neglect of the development of ports, inadequate stockpiles in forward areas, and a shortage of POL as increased German resistance stalled the American advance. The difficulties were exacerbated by the poor supply discipline of the American soldier. While the logistical system had facilitated a great victory, these factors would be keenly felt.

Background

During the 1920s and 1930s, the United States had developed and periodically updated War Plan Black for the possibility of a war with Germany. Planning began in earnest at the ABC-1 Conference in Washington, DC, in January to March 1941, where agreement was reached with the UK and Canada on a Europe first strategy in the event of the US being forced into a war with both Germany and Japan.[1] A US military mission to the UK called the Special Observer Group (SPOBS) was formed under the command of Major General James E. Chaney, a United States Army Air Corps officer who had been stationed in the UK since October 1940 to observe air operations. Chaney opened SPOBS headquarters at the US Embassy at 1 Grosvenor Square, London, on 19 May 1941, and moved it across the street to 20 Grosvenor Square two days later. Henceforth, Grosvenor Square would be the hub of American activity in the UK.[2]

In the wake of the American entry into World War II in December 1941, the War Department activated the United States Army Forces in the British Isles (USAFBI) under Chaney's command on 8 January 1942.[3][4] Under the ABC-1 and Rainbow 5 war plans, the United States would participate in the defense of the UK,[5] but the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, General George C. Marshall had a larger role in mind. In April 1942, Marshall and Harry L. Hopkins, the advisor to the president, visited the UK, and obtained the approval of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the British Chiefs of Staff Committee for Operation Bolero, the buildup of US forces in the UK with the aim of eventually mounting a cross-channel attack. With this prospect in mind, Chaney asked the War Department for personnel to form a Services of Supply (SOS) command.[6]

Chaney's proposed SOS organizational structure did not meet with the approval of the War Department. On 9 March 1942, Marshall had conducted a sweeping reorganization that had consolidated logistical functions in the US under the United States Army Services of Supply (USASOS), headed by Major General Brehon B. Somervell. Chaos had resulted during World War I because the organization of the SOS in France was different from that of the War Department, and an important lesson of that war was the need for the theater SOS organization to parallel that in the United States.[7] Marshall and Somervell wanted it led by someone familiar with the new organization, and selected Major General John C. H. Lee. Each branch head in Somervell's headquarters was asked to nominate its best two men, one of whom was selected by Somervell and Lee for Lee's SOS headquarters, while the other remained in Washington. Lee held the first meeting of his new staff on 16 May, before departing for the UK on 23 May, and Chaney formally activated SOS the following day.[8]

On 8 June 1942, the War Department upgraded USAFBI to the status of a theater of war, becoming the European Theater of Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA). Chaney was recalled to the US, and replaced by the chief of the Operations Division at the War Department, Major General Dwight D. Eisenhower.[7][9] Accommodation for the SOS headquarters was initially provided in an apartment building at No 1 Great Cumberland Place in London, but something larger was required. Brigadier General Claude N. Thiele, the SOS Chief of Administrative Services, found 500,000 square feet (46,000 m2) of office space in Cheltenham, a spa town 90 miles (140 km) northwest of London. Intended as an evacuation point for the British War Office in the event that London had to be evacuated, the staff stationed there were in the process of moving back to London. The site had adequate road, rail and signal communications, but the distance from London was a disadvantage. Lee opened SOS headquarters in Cheltenham on 25 July.[10]

Lee announced a regional organization of SOS on 20 July. It was divided into base commands corresponding to the British Army's territorial commands. The Northern Island Base Section, under Brigadier General Leroy P. Collins, with its headquarters at Belfast, included all of Northern Ireland; the Western Base Section, under Davison, had its headquarters at Chester, and corresponded to the British Army's Scottish and Western Commands; the Eastern Base Section, under Colonel Cecil R. Moore, with its headquarters at Watford, corresponded to the British Northern and Eastern Commands; and the Southern Base Section, under Colonel Charles O. Thrasher, with its headquarters at Wilton, Wiltshire, corresponded to the British Southern and South Eastern Commands.[11] A London Base Command was created under the command of Brigadier General Pleas B. Rogers on 21 March 1943.[12] Over time each of the base sections acquired its own character, with the Western Base Section principally concerned with the reception of troops and supplies, the Eastern with supporting the Air Force, and the Southern with hosting marshalling and training areas.[13] The doctrinal concept behind the base section concept was of "centralized control and decentralized operation", but reconciling the two proved difficult in practice.[14]

Planning and preparations

Bolero

Bolero was derailed by the decision taken in July 1942 to abandon Operation Sledgehammer, the proposed 1942 cross-channel attack, in favor of Operation Torch, an invasion of French Northwest Africa. This made Operation Roundup, the prospective cross-channel attack in 1943, unlikely,[16] but it died hard in the UK.[17] Doubtful that sufficient shipping was available to support both Bolero and Torch, Somervell ordered all construction work in the UK to cease, except on airfields,[17] but the British government went ahead anyway, using materials and labor supplied under Reverse Lend-Lease. After the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, American resources became available again. Eventually, the works completed included 6,489,335 square feet (602,879 m2) of covered storage, 37,915,645 square feet (3,522,479 m2) of open storage and hard standings, and facilities for storage of 169,320 long tons (172,040 t) of petrol, oil and lubricants (POL).[18]

Roundup was not carried out, but Bolero survived, strengthened by the decision at the Trident Conference to mount the cross-channel attack with a target date of 1 May 1944. The planners at Trident envisioned shipping 1.3 million US troops to the UK by that date. Effecting this depended on the ability of the ports in the UK handling up to 150 ships per month.[19] Progress was disappointing, but record shipments of men in the last quarter of the year boosted the strength of ETOUSA to 773,753 by the end of 1943, of whom 220,200 were in the SOS.[20]

To take advantage of the longer daylight hours of summer, a system of preshipment was instituted, whereby unit equipment was shipped to the UK in advance of the units. Rather than lose training time packing all its equipment, personnel could sail to the UK, and draw a new set of equipment there. The major obstacle to the idea was that not all commodities were available in surplus in the US. Indeed the Army Service Forces (ASF), as USASOS had been renamed on 12 March 1943,[21] had difficulty filling the available shipping. Of 1,012,000 measurement tons (1,146,000 cubic metres) of cargo space available in July, only 780,000 measurement tons (880,000 cubic metres) were used; of 1,122,000 measurement tons (1,271,000 cubic metres) available in August, only 730,000 measurement tons (830,000 cubic metres). Of the 2,304,000 measurement tons (2,610,000 cubic metres) shipped in May through August, 39 percent was preshipped cargo. This rose to 457,868 measurement tons (518,615 cubic metres) or 54 percent of the 850,000 measurement tons (960,000 cubic metres) shipped in November, but most of this was consumed re-equipping three of the four divisions transferred from NATOUSA.[22]

The main points of entry for US cargo were the Clyde and Mersey River ports, and those of the Bristol Channel; ports on the south and east coasts of the UK were subject to attack by German aircraft and submarines, and were avoided until late 1943, when shipments began to exceed the capacity of the other ports. The Clyde ports of Glasgow, Greenock and Gourock were remote from the main supply depots, but were used as the main debarkation points for US troops, accounting for 873,163 (52 percent) of the 1,671,010 US personnel arrivals, but only 1,138,000 measurement tons (1,289,000 cubic metres) (8 percent) of cargo.[23] The majority of troops travelled across the Atlantic on ocean liners like the RMS Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mary. Marking three round-trip voyages per month carrying up to 15,000 passengers each time, these two liners alone carried 24 percent of troops arrivals. They were supplemented by other liners, including the RMS Aquitania and Mauretania, and the SS Île de France, Nieuw Amsterdam and Bergensfjord, which accounted for another 36 percent.[24] The troops debarked into ship's tenders, and boarded quayside trains to their destinations.[23]

The Bristol Channel ports of Swansea, Cardiff, Newport and Avonmouth, and the Mersey ports of Liverpool, Garston, Manchester and Birkenhead handled 9,750,000 measurement tons (11,040,000 cubic metres) (70 percent) of the cargo brought to the UK, including most of the heavy items like tanks, artillery pieces and ammunition. This was not accomplished without difficulty; most of the cargo handling equipment was old and outdated, and it was not possible to follow the standard US practice of moving goods from the quayside on pallets with forklifts. Trade unions in the United Kingdom opposed the use of military labor except when civilian labor was unavailable, but this ban was lifted when the volume of cargo became too great, and by May 1944 fifteen US port battalions were working the UK ports [23]

SOS found the textbook concept of shipping cargo from the port to distribution centers, sorting it there, and despatching it to branch depots too extravagant in its use of scarce depot space and the overburdened British railway system. Moreover shipping manifests were often found to be incomplete, inaccurate or illegible, and despite being sent by air mail somehow still frequently failed to arrive in advance of the cargo. SOS ultimately persuaded a reluctant ASF to accept a system whereby every item shipped was individually labelled with a requisition number that provided a complete UK destination address.[25]

The railways were used to move cargo wherever possible, as the narrow rural roads and village streets of rural England were not conducive to use by large trucks, but as cargo volumes increased, road transport had to be resorted to, and in the eight months from October 1943 to May 1944, trucks carried 1,000,000 long tons (1,000,000 t), or about a third of the cargo from the ports. The railways had challenges of their own, with limited head room and tunnel clearances that impeded the carriage of bulky items like tanks. Locomotives were in short supply and in 1942 the British railways arranged for 400 2-8-0 locomotives to be shipped from the US under Lend-Lease. The order was later increased to 900, and in 1943 they arrived at a rate of fifty per month.[26]

The US buildup in the UK was largely accomplished in first five months of 1944. In this period, an additional 752,663 troops arrived, bringing the total theater strength to 1,526,965. Of these, 459,511 were in the SOS.[27] Some 6,106,500 measurement tons (6,916,700 cubic metres) of cargo arrived in the same period. Clearing it involved running 100 special freight trains with up to 20,000 loaded cars each week. The limit on ship arrivals was raised from 109 to 120 in March, then to 140. Shipments in excess of the previously agreed limits were possible only because of the postponement of the invasion date from May to June.[28] This postponement, primarily to gain an extra month's production of landing craft for the enlarged landing plan,[29] cost a month in which the weather over the English Channel was the best it had been in forty years. May was also the month when the Germans sowed Cherbourg Harbor with oyster mines.[30]

The pressure on the UK transportation system became acute in May as Overlord commenced and the troops began moving to their staging areas. By 18 May SOS was forced to inform the New York Port of Embarkation that no more than 120 ships could be accepted. By this time the New York Port of Embarkation had a backlog of 540,000 measurement tons (610,000 cubic metres) of cargo and a deficit of 61 ships that were required to move it. This meant that the Third Army would have only 60 percent of its wheeled vehicles by the end of June.[28]

Organization

A separate North African Theater of Operations (NATOUSA) was created under Eisenhower on 6 February 1943, and Lieutenant General Frank M. Andrews succeeded him at ETOUSA. Andrews had SOS headquarters moved back to London, but his tenure in command was brief, as he was killed in an air crash on 3 May 1943. He was replaced by Lieutenant General Jacob L. Devers.[31] The British had already activated the 21st Army Group in July 1943, and Devers prevailed on the War Department to authorize American counterparts.[16] The First United States Army Group was activated on 16 October 1943,[32] with its headquarters at Bryanston Square in London. Devers had Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley reassigned to ETOUSA to command it. Bradley commanded both the First Army Group and the First United States Army (FUSA), which opened its headquarters in Bristol on 20 October,[33] and assumed control of all US ground forces in the UK three days later.[34]

An outcome of the 1943 Casablanca Conference was that in April 1943 the British Chiefs of Staff designated British Lieutenant General Frederick E. Morgan as the Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander, with the immediate mission of planning the cross-channel operation, codenamed Operation Overlord. The staff he gathered around him became known by his own abbreviation, COSSAC.[35] Eisenhower returned to the UK on 16 January 1944, and became the Supreme Allied Commander. COSSAC was absorbed into his new headquarters, known as the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). Eisenhower also took over ETOUSA, but tended to rely on his SHAEF staff.[36] With the formation of SHAEF and FUSAG, ETOUSA lost most of its roles, and was consolidated with SOS.[37]

From February 1944 on, SOS was increasingly referred to as the Communications Zone (COMZ),[38] although this did not become official until 7 June.[39] On 9 February SHAEF ordered FUSAG and COMZ to supply American liaison elements to 21st Army Group, which would control the First Army in the opening stages of Operation Overlord. ETOUSA had already activated its element two days before as the Forward Echelon, Communications Zone (FECOMZ). Brigadier General Harry B. Vaughan, the Western Base Section commander, was appointed to command it, with Colonel Frank M. Albrecht as his chief of staff.[40][41]

Another organization activated on 7 February was the Advance Section (ADSEC), under the command of Colonel Ewart G. Plank. Experience in Italy had demonstrated the value of a logistical agency that worked closely with the army it was supporting. ADSEC would take over the operation of base areas, supply dumps and communications from FUSA as it moved forward. In the initial stages of Overlord, ADSEC would be attached to FUSA.[42] COMZ also began organizing base sections for service in France. In March the five districts of the Eastern Base Section were consolidated into one, which became the VIII District of the Western Base Section in April. On 1 May, Base Section No. 1 was activated under the command of Colonel Roy W. Growler. The new section was held in readiness for service in Brittany. On 1 June Base Section No. 2, under the command of Brigadier General Leroy P. Collins, was activated.[43]

Planning

The logistical planners saw the campaign unfolding in three stages. In the first, an automatic supply system would be used, with materiel despatched on a predetermined schedule. In the second stage, which would occur after a lodgment was secured and supply depots began functioning, the system would become semi-automatic, with items like ammunition shipped on the basis of status reports. In the third stage, which would occur when the major ports were opened and the supply system was functioning smoothly, all items would be sent on requisition. In the event, the war ended before the third stage was achieved.[44]

Since the first three months of supply shipments were determined in advance, and the first two weeks already loaded on ships, three expedients were prepared to cover unanticipated shortfalls. The first was codenamed the "Red Ball Express". Starting on D plus 3, 100 measurement tons (110 cubic metres) per day were set aside for emergency requests. Such shipments would be expedited. The second, codenamed "Greenlight", provided for 600 measurement tons (680 cubic metres) of ammunition and engineer equipment to be substituted for scheduled shipments of engineer supplies. This would become available from D plus 14 onwards, and Greenlight supplies would take up to six days for delivery. Finally, supplies were packed with parachutes for aerial delivery to isolated units, and plans were made for the delivery of 6,000 pounds (2,700 kilograms) of supplies per day by air once airfields had been secured, with 48 hours warning.[45]

Logistical support of the armies on the continent depended on the capture and repair of ports. Plans were drawn up for the rehabilitation of eighteen ports in Normandy and Brittany. The task was assigned to port construction and repair (PC & R) groups. Each had a headquarters and headquarters company with specialists trained in port reconstruction, and a pool of heavy construction equipment with operators, which were supplemented by engineer troops and civilians, dump truck companies, port repair ships and dredges. Seven ports were expected to be captured and opened in the first four weeks: Isigny-sur-Mer, Cherbourg, Grandcamp, Saint-Vaast-sur-Seulles, Barfleur, Granville and Saint-Malo. Except for Cherbourg, all were small and tidal, and unable to berth vessels drawing more than 14 to 15 feet (4.3 to 4.6 m) at high water, which ruled out larger vessels. Much therefore depended on the early opening of Cherbourg, which was expected to occur by D plus 11, and was expected to handle 6,000 measurement tons (6,800 cubic metres) per day by D plus 30, and 8,000 measurement tons (9,100 cubic metres) per day by D plus 90, more than the other six ports combined.[46]

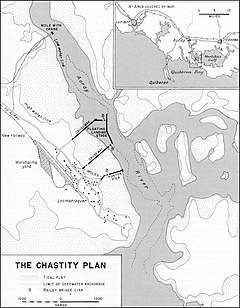

In the longer term, the US forces would rely on the ports of Brittany, principally Brest, Lorient and Quiberon Bay. Along with Saint-Malo, they were expected to have a capacity of 17,500 measurement tons (19,800 cubic metres) per day. Of this, 10,000 measurement tons (11,000 cubic metres) per day were expected to come through Quiberon Bay, as it was anticipated that the ports would suffer considerable damage in the fighting, or through German demolitions. Studies indicated that Quiberon Bay had an anchorage sufficient for 200 ships, 3,000 yards (2,700 m) of beaches with the required slope for landing craft, and four minor ports close by where deep water piers could be constructed. A detailed plan known as Operation Chastity was drawn up to develop the area.[47]

The Overlord plan called for the early capture of Cherbourg, and a rapid American advance to secure the Brittany ports and Quiberon Bay. Crucially, the logistical plan called for a one-month pause at the Seine River, which was expected to be reached by D plus 90, before advancing further.[48] The expectation of an advance at a proscribed rate, while necessary for planning purposes, built inflexibility into a logistics plan that already had little margin for error. Staff studies confirmed that Overlord could be supported if everything went according to plan. No one expected that it would.[49][50]

Assault

The Southern Base Section consisted of four districts, numbered XVI, XVII, XVIII and XIX. The XVIII District, under the command of Colonel Paschal N. Strong, was responsible for mounting Force O, the assault force for Omaha Beach, while the XIX district, under the command of Colonel Theodore Wyman Jr., handled Force U, the assault force for Utah Beach. The South Base Section coast was divided into nine areas, lettered A to D in the XVIII District and K to O in the XIX District. Together they contained 95 marshalling camps with a capacity for 187,000 troops and 28,000 vehicles. The other two districts, the XVI and XVII, were responsible for mounting glider-borne elements of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions.[51]

In the opening phase of Overlord, supplies would arrive over the beaches. Operation of the beachheads was assigned to the engineer special brigades. Their name was misleading, for in addition to three engineer battalions, each contained amphibious truck and port companies, and quartermaster, ordnance, medical, military police, signals and chemical warfare units. Along with bomb disposal squads, naval beach parties, maintenance and repair parties and other troops attached for the mission, each had a strength of 15,000 to 20,000 men.[52]

Utah Beach would be operated by the 1st Engineer Special Brigade, under the command of Brigadier General James E. Wharton; Omaha by the Provisional Special Brigade Group, consisting of the 5th and 6th Engineer Special Brigades and the 11th Port, commanded by Brigadier General William M. Hoge.[53] The 11th Port had a strength of over 7,600 men; it included four port battalions, five amphibious truck companies, three quartermaster service companies, and three quartermaster truck companies.[54]

The engineers landing on Omaha Beach on D-Day, 6 June, found the beach swept by artillery and automatic weapons fire that the infantry was unable to suppress, and the beach littered with disabled vehicles and landing craft. Only five of the sixteen engineer teams arrived at their assigned locations, and they had only six of their sixteen tank dozers, five of which were soon knocked out. They were only able to clear five narrow lanes through the obstacles instead of the planned sixteen 50-yard (46 m) gaps.[55] As the infantry advanced, the engineers filled in anti-tank ditches, cleared minefields, demolished obstacles, opened three exits, and established the first supply dumps.[56]

The first waves came ashore on Utah Beach about 2,000 yards (1,800 m) south of the intended landing beaches. The beach fortifications were much weaker than the intended beaches, but the distance between the low and high watermarks was much greater. Because the beach obstacles were fewer than expected, the engineers were able to clear the entire beach of obstacles rather than just 50-yard (46 m) gaps. However, beach dumps could not be established as planned because the areas had not been captured.[57]

Individual riflemen arriving on the beaches were overburdened, carrying at least 68 pounds (31 kg) of equipment. This overburdening had been noted during landing exercises, but instead of reducing the load, another 15 pounds (6.8 kg) had been added. The inability of the troops to move quickly had lethal consequences, especially on the deadly Omaha beach.[58] Unneeded equipment was often discarded. The demonstration of the Army's prodigality inculcated a culture of wastefulness that had undesirable longer term consequences.[59]

Build-up

Shipping

Build up priority lists had been drawn up months in advance that specified in what order units were to embark for Normandy during the first ninety days. To regulate the movement of ships and landing craft with maximum economy, a special organization was established called Build Up Control (BUCO). This operated under the tactical commanders, FUSA in the US case, on the British committee system, with representatives of the Allied Naval Commander, Ministry of War Transport and War Shipping Administration. BUCO was chaired by British Brigadier G. C. Blacker, with Lieutenant Colonel Eli Stevens as the head of the US Zone Staff. [60] It had three subordinate agencies: Movement Control (MOVCO), which issued orders for unit movements; Turnaround Control (TURCO), which liaised with the Navy and engineer special brigades; and Embarkation Control (EMBARCO), which handled the location of units and the availability of space in the marshaling areas.[61]

The detailed shipping plan soon fell apart. Very little cargo was landed on the first day, putting Overlord behind schedule from the start. By midnight on 8 June, only 6,614 measurement tons (7,492 m3) of the planned 24,850 long tons (25,250 t) had been discharged, just 26.6 percent of the planned total. This rose to 28,100 long tons (28,600 t) of the planned 60,250 long tons (61,220 t), or 46 percent of the planned total by midnight on 10 June.[62] Emergency beach dumps were established by the engineer special brigades on 7 and 8 June, and the planned inland dumps were opened over the next few days. The dumps were under sniper fire, and on 10 June artillery ammunition was taken from its boxes and carried by hand to the batteries. A consolidated ammunition dump was established at Formigny on 12 June, and FUSA immediate took change of it. The following day it assumed control of all dumps from the engineer special brigades.[63]

The standard cargo vessel, the Liberty ship, carried up to 11,000 long tons (11,000 t) of cargo.[64] It had five hatches; two had 50-long-ton (51 t) booms, and three with smaller 6-to-9-long-ton (6.1 to 9.1 t) booms. In their haste to unload the ships, the crews overloaded the booms, occasionally resulting in breakages. Cargo was not containerized, but transported in bulk in bags, boxes, crates and barrels. Cargo nets were spread out on the deck, and cargo piled on them. They were then lifted over the side on the ship's boom, and deposited in a waiting craft.[62]

One of the most useful unloading craft was the Rhino ferry, a powered barge constructed from pontons.[62] The other mainstay of the unloading effort was the 2.5-measurement-ton (2.8 m3) amphibious truck known as the DUKW (and pronounced "duck"). DUKWs were supposed to land on D-Day, but most were held offshore and arrived the following day.[65] The Omaha and Utah beaches remained under sporadic artillery and sniper fire for several days, and as a result the naval officer in charge would not permit ships to anchor close to shore on the first two days.[62] Some were as much as 12 to 15 miles (19 to 24 km) offshore. This increased turnaround time for the unloading craft, especially the DUKWs, which were slow in the water. In some cases, DUKWs ran out of fuel. When this happened, their pumps failed, and they sank.[65]

The unloading craft were frequently overloaded, increasing wear and tear, and occasionally causing them to capsize. Ideally, a DUKW reaching the shore would be met by a mobile crane that could transfer the load to a waiting truck that could take it to the dump, but there were shortages of both trucks and cranes in the early weeks, and DUKWs had to take cargo to the dumps themselves. Insufficient personnel at the dumps for unloading further slowed turnaround, as did the practice of crews whose priority was getting the ship unloaded, of unloading more than one category of supply at once, resulting in a trip to more than one dump. This was resolved only when ships started being loaded with one category of supply only. Cargo was deposited on the beach at low tide, and if not swiftly cleared was likely to be swamped by the rising tide.[62]

The movement of troops into the marshaling areas had been pre-scheduled, and was already under way when D-Day was postponed for 24 hours. Troops continued to pour into the marshaling areas even though embarkation had halted, and they became overcrowded. This was exacerbated by the slow turnaround of shipping. The stowage and loading plans could not be adhered to when the designated ships failed to arrive as scheduled, and troops and cargo in the marshaling areas could not be sorted into ship loads. The situation became so bad that the flow of troops to the ports became insufficient to load the available ships, and on 12 June Stevens diverted idle shipping to the British so it was not wasted. Thereafter, troops and cargo moved to the ports and were loaded on the next available ship or landing craft. Loading plans were worked out on the spot. Had the Germans sank a ship it would have been highly embarrassing to the War Department, as no proper embarkation records were kept for a time. Some units became lost in the confusion. Major General Leonard T. Gerow, the commander of V Corps, personally returned the UK to locate a missing unit that the Southern Base Section had claimed had been shipped, but which was found still in its assembly area.[66]

A major problem was ships arriving without manifests, which were supposed to have been shipped in advance by air or naval courier, but aircraft could not get through and the courier launches were often delayed. Navy and Transportation Corps officers went from one ship to the next searching for items that were desperately required. FUSA would then declare what it wanted discharged.[67] Selective unloading left half-empty ships with supplies not immediately required standing offshore, further exacerbating the problem of ship turnaround. Desperate measures were taken. The most controversial was ordering the "drying out" LSTs.[62] This involved beaching the LST on a falling tide, discharging at low tide, and then re-floating the LST on the rising tide.[68] The procedure had been performed successfully in the Mediterranean and the Pacific, but with the high tidal range and uneven beaches of Normandy, naval officials feared that the LSTs might break their backs. Drying out commenced tentatively on 8 June and soon became a standard practice.[62]

On 10 June, the First Army ordered the selective discharging of LSTs and LCTs to cease; this was extended to all vessels the following day. Discharge at night under lights began on 12 June despite the risk of German air attack. The backlog of ships was eventually cleared by 15 June. Nonetheless, the manifest problem persisted. When a critical shortage of M1 mortar ammunition developed in July, all available ammunition was shipped from the UK, but the First Army did not know where the ammunition was or when it arrived. Ordnance personnel were forced to conduct searches of ships looking for it. Thus, a critical shortage continued even though 145,000 long tons (147,000 t) of ammunition lay offshore.[62]

Mulberry harbor

The decision to land in Normandy meant that ports would not be captured quickly; the Brittany ports were not expected to be in operation until D plus 60. Until then, the Allied armies would have to rely on the beaches, but the weather forecast was not promising. Meteorological records showed that 25 days of good weather could be expected in June, but there were normally only two quiet spells of good weather for four days running between May and September. The tidal range in Normandy was about 12 feet (3.7 m); low tide uncovered about one-quarter of a mile (0.40 km) of beach, and water deep enough for coasters, which drew 12 to 18 feet (3.7 to 5.5 m) of water, was another one-half a mile (0.80 km) further out.[69]

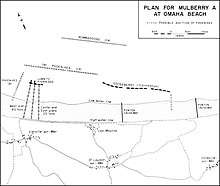

The solution the COSSAC planners adopted was innovative and audacious: to build a prefabricated harbor. While ports like Dover and Cherbourg were artificial in the sense that their sheltered harbors had been created through the construction of breakwaters, there was a significant difference between building Dover in seven years in peacetime, and prefabricating an artificial port in a matter of months, and erecting it in two weeks in wartime.[69] Originally, there was to be one artificial port, at Arromanches in the British sector, but by October 1943 COSSAC added a second one at Saint-Laurent in the American sector. At this time the project acquired a codename: Mulberry, with the American port becoming Mulberry A and the British one Mulberry B. British Rear Admiral Sir William Tennant was in charge of the operation, with the American Captain A. Dayton Clark in charge of Mulberry A.[70][71]

The Mulberry harbor had three breakwaters. The outermost was made up of bombardons, 200-foot (61 m) long cruciform floating steel structures. These were laid out in a straight line. Then came the phoenixes, 60-by-60-by-200-foot (18 by 18 by 61 m) concrete caissons that weighed between 2,000 and 6,000 long tons (2,030 and 6,100 t). These were sunk in about 5 1⁄2 fathoms (10.1 m) of water to form an inner breakwater. Finally, there was the gooseberry, an inner breakwater formed by sinking obsolete vessels known as corncobs in about 2 1⁄2 fathoms (4.6 m) of water. Plans called for Mulberry A to have three piers, two of 25 long tons (25 t) capacity, and one of 40 long tons (41 t).[71] Towing the mulberries' components was estimated to require 164 tugs, but only 125 were available, and 24 of these were temporarily diverted to tow barges. The target date for completion of the mulberries was therefore pushed back from D plus 14 to D plus 21.[72]

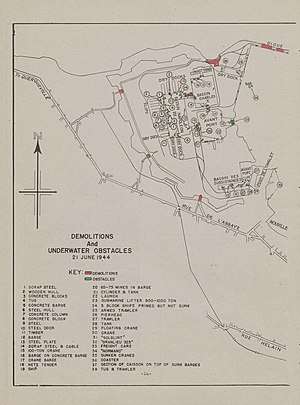

Clark arrived off Omaha beach with his staff on 7 June, and the first three corncobs were scuttled under fire that day. The gooseberry was completed by 10 June, and by 17 June all 24 of the bombardons, 32 of the 51 phoenixes were in place, and the central LST pier was in use. On its first day of operation, a vehicle unloaded over the pier every 1.16 minutes. Seabees (Naval construction personnel) completed the first of the 2,450-foot (750 m) ponton causeways on 10 June, and the second five days later. The planned harbor installation at Utah Beach was much smaller, consisting of just two ponton causeways and a gooseberry with ten corncobs. The corncobs began arriving on 8 June, and came under fire from German artillery. Two were hit, and sank, but in approximately the intended position, albeit spaced too far apart. A third also sank slightly out of position when the tug towing it cut it loose to avoid the shelling. The remainder were scuttled in the correct locations, and the gooseberry was completed on 13 June. The first ponton causeway was opened that day, followed by the second three days later.[73]

By 18 June, 116,065 long tons (117,927 t) of supplies had been landed, 72.9 percent of the planned 159,530 long tons (162,090 t), although only 40,541 (66 percent) of the planned 61,367 vehicles had arrived. The First Army estimated that it had accumulated 9 days' reserves of rations, and five days' of POL. On the other hand, 314,504 (88 percent) of the planned 358,139 American troops had reached the beaches, representing eleven of the intended twelve divisions. In addition, 14,500 casualties had been evacuated by sea and 1,300 by air, and 10,000 prisoners had been shipped back to the UK.[74]

But on 19 June, the Normandy beaches were hit by a storm that lasted for four days. Although the worst June storm in forty years, it was not a severe one; wind gusts reached 25 to 32 knots (46 to 59 km/h), and therefore never reached gale force. Waves reached 8 1⁄2 feet (2.6 m).[75][76] Nonetheless, the damage was considerable. Nearly a hundred landing craft were lost, and only one of the twenty Rhino ferries remained operational. Damaged craft were strewn over the beach, partially blocking every exit. The storm interrupted unloading for four days, resulting in the discharge of only 12,253 long tons (12,450 t) of stores instead of the planned 64,100 long tons (65,100 t), and 23,460 troops instead of the 77,081 scheduled.[77]

The American Western Naval Task Force commander, Rear Admiral Alan G. Kirk, surveyed the damage. The bombardons had failed completely, while the piers and phoenixes had been unable to withstand the pounding of the waves, and had been heavily damaged. Kirk decided that Mulberry A was a total loss, and should not be rebuilt, although the gooseberry should be reinforced with a dozen additional blockships. Many American officials had been skeptical about the value of the artificial port concept from the very beginning, but had held their tongues, knowing that it had high-level official support. The British Mulberry B had not been as badly damaged, as the Calvados Rocks had given it some additional protection, and the British still were still determined to complete their artificial port to a standard that could withstand the autumn gales. The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Winston Churchill, assured Eisenhower that the project still had his full support. Mulberry B was repaired and reinforced, in some cases using components salvaged from Mulberry A. Expected to handle 6,000 long tons (6,100 t) per day, Mulberry B actually averaged 6,765 long tons (6,874 t) per day over three months, accounting for 48 percent of the tonnage unloaded in the British sector.[78][79]

This left the American forces dependent on some small ports and unloading over the beaches. By 30 June, 70,910 of the planned 109,921 vehicles (64.5 percent) had been landed, and 452,460 (78 percent) of the planned 578,971 troops. The deficit in personnel consisted entirely of service and support troops; all eleven divisions planned for had arrived, along with the two airborne divisions which were to have been withdrawn to the UK but had been retained in France.[80]

Air supply

Air supply was handled by the Allied Expeditionary Air Force (AEAF). The Combined Air Transport Operations Room (CATOR) was established as a special staff section of AEAF Headquarters in Stanmore, and it took bids for air transport. The first major use of air supply was in support of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions on 7 June, when 208 aircraft were despatched. Of these, 64 had to return to the UK without dropping their loads owing to bad weather. Of the 250 short tons (230 t) of supplies despatched 155 short tons (141 t) were dropped, of which 90 percent was recovered. In the following week, supplies were airdopped to the 101st Airborne Division on request. A misreading of ground panels by reconnaisance aircraft led to the delivery of 118 planeloads of cargo that were not required. Some supplies such as 105 mm howitzers were delivered by glider. Emergency airdrops were made to a field hospital on 8 June, and to an anti-aircraft unit isolated by the 19 June storm. [81] Only one administrative airfield was available by the end of July, at Colleville-sur-Mer near Omaha Beach.[82] Nonetheless, Cross-Channel air flights commenced on 10 June.[83] Air supply was heavily used during the week after the storm, with 1,400 long tons (1,400 t) of supplies, mostly ammunition, landed. By the end of July, 7,000 long tons (7,100 t) had been delivered by air.[81] In addition, 25,959 casualties were evacuated by air in June and July, compared to 39,118 by sea.[83]

Ordnance

The nature of the fighting in the Normandy hedgerows created shortages of certain items. A heavy reliance on M1 mortars not only led to a shortage of ammunition, but a shortage of the mortars themselves as the Germans targeted them. On 3 July, the First Army ordered tank, armored field artillery, and tank destroyer battalions to turn in their mortars for reallocation to infantry units.[84] A shortage of bazookas was similarly addressed by taking them from service units and redistributing them to the infantry. The Germans also made a special effort to eliminate the man with the Browning automatic rifle (BAR), as the BAR represented most of an infantry squad's firepower. Another item with a higher than expected loss rate was the M7 grenade launcher. When this device was attached to the M1 Garand rifle, it disabled the rifle's semi-automatic function, so the rifle could not be fired normally when it was in place. Accordingly, they were quickly discarded after use in combat, resulting in a high loss rate. By mid-July, the First Army reported a shortage of 2,300 M7 grenade launchers.[85]

Although ammunition expenditure did not exceed expected usage, it did not arrive at the planned rate either, resulting in shortages. The First Army gave high priority to the unloading of ammunition. The hedgerow fighting soon generated shortages of small arms ammunition and hand grenades. These were alleviated in the short term by emergency shipments by air, and in the medium term by allotting ammunition the highest priority for shipment instead of POL. On 15 June the First Army imposed restrictions on the number of rounds per gun per day that could be fired. In part this was because deliveries consistently fell short of targets, but the main problem that the First Army sought to address was excessive and unreported stocks held by artillery units, which reduced the reserves held at Army level. The 19 June storm prompted emergency action. the First Army limited expenditure to a third of a unit of fire per day, arranged for 500 long tons (510 t) per day to be delivered by air for three days, ordered coasters carrying ammunition to be beached, and called forward five Liberty ships in UK waters that had been prestowed with ammunition. [86]

A unit of fire was a somewhat arbitrary measurement for accounting purposes, and was different for each type of ammunition.[87] It was 133 rounds for the 105 mm howitzer, 75 rounds for the 155 mm howitzer, 50 rounds for the 155 mm gun, and 50 rounds for the 8 inch howitzer.[88] The divisions responded to the restrictions on the use of field artillery by employing tank destroyers and anti-aircraft guns as field artillery, as their ammunition was not rationed. On 2 July, the First Army imposed a new set of restrictions: expenditure was not to exceed one unit of fire of the first day of an attack, half a unit of fire on the second and subsequent days of an attack, and a third of a unit of fire on other days. Consumption in excess of the limits had to be reported to the First Army, with an appropriate justification. In practice, ammunition usage continued to be heavy, exacerbated by wasteful practices like unobserved firing and firing for morale effect by inexperienced units. By 16 July, the First Army stocks of 105 mm ammunition were down to 3.5 units of fire, and 81 mm mortar ammunition was at a critically low 0.3 units of fire. Ammunition was being unloaded at a rate of 500 long tons (510 t) per day, which was insufficient, resulting in the First Army stocks being depleted at a rate of 0.2 units of fire per day. the First Army once again imposed strict rationing on 16 July, but expenditure was well below the limits owing to most of the tubes going silent as they moved into new gun positions for the upcoming Operation Cobra attack on 25 July.[86]

The limitations of the M4 Sherman tank's 75 mm gun had already been recognized to some extent, and the theater had received 150 Shermans armed with the high-velocity 76 mm gun. A few weeks of combat in Normandy laid plain that the Sherman, even when equipped with the 76 mm gun, was outclassed by the German Tiger I, Tiger II and Panther tanks. The chief of the ETOUSA Armored Fighting Vehicles and Weapons Section, Brigadier General Joseph A. Holly, met with commanders in the field on 25 June, and then went to the United States in July to urge the expedited delivery of Shermans armed with the 105 mm howitzer, and of the new M36 tank destroyer, which was armed with a 90 mm gun.[85][89] In the meantime, 57 recently-received Shermans armed with the 105 mm howitzer were shipped to Normandy from the UK.[85] Consideration was given to obtaining the British Sherman Firefly, which mounted the powerful 17-pounder anti-tank gun, but the British were overwhelmed with orders for them from the British Army.[89][90] It was useless arguing that American equipment was adequate; American propaganda declared that the American fighting man was the best equipped in the world, and when confronted with evidence to the contrary, everyone from Eisenhower down felt short changed.[59][90]

Subsistence

American soldiers were also skeptical of the claim that they were the best-fed soldiers of all time. The US Army's standard garrison ration was called the A-ration. The B-ration was A-ration without its perishable components. The C-ration consisted of six 12-US-fluid-ounce (350 ml) cans, three of which contained meat combinations (meat and vegetable hash, meat and beans, or meat and vegetable stew), and the other three biscuits, hard candy, cigarettes, and a beverage in the form of instant coffee, lemon powder or cocoa.[91]

The better-packaged K-ration was designed to be an emergency ration. It contained three meals: a breakfast unit with canned ham and eggs and a dried fruit bar; a supper unit with luncheon meat; and a dinner unit with biscuits and cheese. It also contained Halazone water purification tablets, a four-pack of cigarettes, chewing gum, instant coffee, and sugar. The D-ration was a chocolate bar. The compactness of the K-ration made it the preferred choice of the foot soldiers, but troops with access to transport and heating preferred the C-ration. Finally, there was the 10-in-1, an American version of the British 12-in-1, which was intended to feed ten men. It could be used by field kitchens, and offered the variety of five different menus. The lemon powder in the C and K rations was those rations' primary sources of vitamin C, but was particularly unpopular with the troops, who frequently discarded it, or used it for tasks like scrubbing floors.[91][92]

The troops landing on D-Day each carried one D-ration and one K-ration; another three rations per man in the form of C- and K-rations were carried with their units. For the first few days all rations landed were C- or K-rations. During the four weeks of Overlord, 60,000,000 rations were delivered to Normandy in vessels pre-stowed in three to eight 500-long-ton (510 t) blocks at the New York Port of Embarkation. This facilitated the shift to 10-in-1 packs over the less popular C- and K-rations; 77 percent of rations in the first four weeks were in the form of 10-in-1s. By 1 July, a static bakery was in operation at Cherbourg, and there were seven mobile bakeries in operation, permitting the issue of freshly-baked white bread to commence. By mid-July, 70 percent of the troops were eating B-rations.[91]

POL

Initially fuel arrived packaged in 5-US-gallon (20 l) jerricans. This was a German invention copied by the British; in the US Army it supplanted the 10-US-gallon (38 l) container used in the 1930s. The jerrican had convenient carrying handles, stacked easily and did not shift or roll in storage, and floated in water when filled with MT80. The British version was an exact copy of the German model; the American version, called an Ameri-can by the British, was slightly smaller, with a screw cap onto which a nozzle could be fitted to deal with American vehicles with flush or countersunk fuel tank openings. If a nozzle was not available, the original can with its short spout was much preferred. A US jerrican weighed 10 pounds (4.5 kg) empty, and 40 pounds (18 kg) when filled with MT80, so 56 filled cans weighed one long ton (1.0 t).[93] For Overlord, 11,500,000 jerricans were provided. Of these, 10,500,000 were manufactured in the UK and supplied to the US Army under Reverse Lend-Lease.[94] Jeeps arrived at the beachhead with full tanks and two jerricans of fuel; weapons carriers and small trucks carried five; 2½-ton trucks carried ten; and DUKWs carried twenty.[95]

The standard operating procedure (SOP) with respect to fuel containers was that empties should be returned and swapped for full ones, but the engineer special brigades had no refilling facilities, and did not wish to have the beach supply dumps cluttered with empties, so the First Army issued an order that empties not be returned. Instead, they went to divisional or corps collection points. The relaxation of the full-for-empty SOP was to have undesirable effects later on in the campaign. Bulk POL started to arrive at Isigny on 22 June, and at Port-en-Bessin and Sainte-Honorine-des-Pertes the following day.[96] It had been expected that only the east mole at the Port-en-Bessin terminal could be used, and only by small tankers with a capacity of up to 150 long tons (150 t), but it was found that both the east and west moles could be used, and for tankers up to 1,500 long tons (1,500 t). This allowed one mole to be allocated to the British and one to the Americans.[97]

The POL supply situation was satisfactory throughout June and July, mainly because the rate of advance was much slower than anticipated, resulting in shorter supply lines and lower fuel consumption. The First Army's daily MT80 consumption in July was around 9,500 US barrels (1,130,000 l). Steady progress was made on construction of the Minor System pipeline, and the tank farm at Mont Cauvin received its first bulk MT80 on 25 June. The delay in the capture of Cherbourg led to the extension of the Minor System beyond what had originally been planned, and eventually 70 miles (110 km) of pipeline were laid instead of the planned 27 miles (43 km). The pipeline carried both MT80 and avgas to Saint-Lô, and later to Carentan. Intended to deliver 6,000 US barrels (720,000 l) per day, it was delivering twice that by the end of July. Storage was similarly greater than planned, 142,000 US barrels (16,900,000 l) instead of the planned 54,000 US barrels (6,400,000 l).[97] Decanting of bulk fuel into jerricans began on 26 June, and by July 600,000 US gallons (2,300,000 l; 500,000 imp gal) were being decanted each day.[98]

By the time Operation Cobra was launched on 25 July, no part of the planned Major System pipeline was in operation. As it was expected to have received 85,000 long tons (86,000 t) of POL by then, receipts lagged considerably. Nonetheless, stocks were roughly what had been intended, because consumption had been much lower. In June, the First Army consumed around 3,700,000 US gallons (14,000,000 l), an average of about 148,000 US gallons (560,000 l) per day, or 55 long tons (56 t) per division slice. This rose to 11,500,000 US gallons (44,000,000 l), an average of about 372,000 US gallons (1,410,000 l) per day, or 75 long tons (76 t) per division slice in July, but still remained far below the expected figure of 121 long tons (123 t) per division slice.[99]

Breakout and pursuit

By the time Operation Cobra was launched on 25 July, Overlord was running nearly forty days behind schedule. The Allies considered an alternative to the Overlord plan called Lucky Strike. This involved defeating the German forces west of the Seine, forcing a crossing of the river, and seizing the Seine ports of Le Havre and Rouen as an alternative to those in Brittany, neither of which had yet been captured. The SHAEF and COMZ staffs considered Lucky Strike a terrible idea, as the Seine ports did not have the capacity to compensate for those in Brittany.[100]

Operation Cobra effected a remarkable turnaround in the operational situation, and by 3 August, Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr.'s Third Army was advancing into Brittany.[101] For some reason, Bradley fixated on Brest, which was only intended to be a port of reception for troops, and Saint-Malo, a minor port, whereas Patton focused on Lorient and Quiberon Bay. There were significant differences in the way Patton, a cavalryman, and Bradley and VIII Corps commander Troy H. Middleton, who were both infantrymen, conceived operational art. When the 4th Armored Division's commander, Major General John S. Wood incorrectly reported that Lorient was too strongly defended to rush, Middleton accepted this assessment.[102][103]

Bradley then ordered Patton to move east, leaving only minimal forces in Brittany.[101] This did not immediately change the plan;[101] Eisenhower informed Marshall that "the rapid occupation of Brittany is placed as a primary task, the difference being that in one case we believe that it would rather easily be done and in the other we would have to fight through the defensive line and commit more forces to the job"[104] But it was the first in a series of critical decisions that subordinated logistical considerations to short-term operational advantage.[101] In the event, Lorient was not captured, and as a result Quiberon Bay could not be developed because the approaches were not cleared. Saint-Malo was secured on 2 September,[105] and Brest on 19 September, but the port facilities were destroyed,[102][106] and SHAEF had abandoned plans to develop Quiberon Bay on 3 September.[107]

By 24 August, the left bank of the Seine had been cleared, and Operation Overlord was completed. In just 30 days, the Allied forces had conducted an advance that had been expected to take 70. Reaching the D plus 90 line on D plus 79 was not a grave concern, as the Overlord plan had sufficient flexibility to allow for a discrepancy of eleven days.[108] The plan called for a pause on the Seine of at least 30 days, but in mid-August the decision was taken to continue the pursuit beyond the Seine. This had even more far-reaching effects than Bradley's 3 August decision.[109] Between 25 August and 12 September, the Allied armies advanced from the D plus 90 phase line to the D plus 350 one, moving through 260 phase lines in just 19 days. Although the planners had estimated that no more than 12 divisions could be maintained beyond the Seine, 16 were by mid-September, albeit on reduced scales.[110]

Base organization

ADSEC headquarters opened in Normandy on 16 June. FECOMZ, now under Albrecht's command, opened its headquarters at Château Servigny and Château Pont Rilly near Valognes on 15 July, but ADSEC remained subordinated to the First Army until 30 July. Indeed, the First Army controlled all US forces in France until 1 August, when the Twelfth United States Army Group and the Third Army became active.[111] The facilities at Valognes were greatly expanded, with tents to accommodate 11,000 personnel and 560,000 square feet (52,000 m2) of hutted office space,[112] and special signal facilities installed to enable it to communicate with the UK and US.[111] COMZ headquarters opened at Valognes on 7 August,[113] a month earlier than originally planned, and FECOMZ therefore never operated in its intended role.[114]

COMZ headquarters was not destined to remain at Valognes for long, for on 1 September it began moving to Paris. As Paris was the hub of road, rail, cable and inland waterway systems, it soon hosted a concentration of supply depots, hospitals, airfields, railway stations and marshaling yards, and inland waterway offloading points, and as such was the logical and perhaps the only suitable location for COMZ headquarters. The move took two weeks to accomplish,[112] with some of the 29,000 staff moving directly from the UK, and consumed motor and air transport at a time when transportation assets were scarce.[115] COMZ headquarters occupied 167 Paris hotels. Eisenhower was not impressed; the move had been conducted without his knowledge, and contrary to his orders that no Allied headquarters be located in Paris without his specific approval.[116]

On 11 July, ADSEC organized the port of Cherbourg as Area No. 1 under the command of Colonel Cleland C. Sibley, the commander if the 4th Major Port. Ten days later it was redesignated that Cherbourg Command, with Wyyman in charge. Over the following week, his headquarters was reinforced with personnel from Base Section No. 3 in England. It was redesignated the Cherbourg Base Section on 7 August, and began taking over the beach area dumps from ADSEC. Finally, on 16 August, it became the Normandy Base Section. Meanwhile, Grower's Base Section No. 1 had arrived at Utah Beach on 3 August, and proceeded to Rennes, where it opened as the Brittany Base Section on 16 August. Base Collins's Section No. 1 moved to Le Mans, where it became the Loire Base Section on 5 September. After Paris was captured, COMZ sent for Rogers's Base Section No. 5, which had been specifically created for the role. It became the Seine Base Section on 24 August,[117] and occupied another 129 Paris hotels.[116]

Base Section No. 4, under the command of Colonel Fenton S. Jacobs, opened at Fontainebleau on 3 September as the Oise Section, and a Channel Base Section was formed under Thrasher. Before either became operational, it was realized that each was better suited to the other's mission, so the two swapped names and roles on 15 September. At the same time the engineering section of the Brittany Base Section, which had been organized with the mission of rehabilitating ports, was transferred to the Channel Base Section. With the departure of the sections and most of the personnel from the UK, the sections there became districts, and were consolidated into the UK Base Section, under Vaughan's command.[117]

A key element of a functional logistics system was the establishment of a series of depots. ADSEC was only authorized to maintain stocks sufficient to supply the daily needs of the armies, with its depots replenished by automatic shipment or requisitions from COMZ. The restricted size of the Normandy lodgment area necessarily resulted in a crowding of the installations, and this problem was compounded by the First Army's reluctance to release dumps under its control until the end of July. The First Army then became the main sufferer from the consequent logistical problems that it caused.[118]

Once the breakout began in earnest, the distances soon became prohibitive for the armies' own transport resources. The Third Army's line of communication ran from the beaches to Laval, a 135 miles (217 km) distant, and then to Le Mans, another 175 miles (282 km) away. ADSEC opened a transfer point at Laval on 13 August, and then one at Le Mans a week later. ADSEC hoped to develop Le Mans as a major supply area, but soon it was too far from the front. The transfer point was moved to Ablis, 20 miles (32 km) east of Chartres, where another attempt was made to establish a major depot area. The transfer point remained at Ablis until 7 September, by which time the Third Army was operating beyond the Moselle, 200 miles (320 km) away, although ADSEC had opened a MT80 supply point at Fontainebleau.[119]

POL

The MT80 supply was adequate for the first month of Operation Cobra, although the Third Army had only meager reserves and depended on daily deliveries. On 3 August it had 515,000 US gallons (1,950,000 l) on hand, representing 1.3 days of supply. In contrast, the First Army held 10.5 days of supply. In view of this disparity, action was taken to reduce the First Army's excess stocks. During the week of 20–26 August, with both armies engaged in pursuit of the retreating Germans, consumption soared, with the First Army burning 501,000 US gallons (1,900,000 l) per day (282,000 US gallons (1,070,000 l) on 24 August alone), compared to the Third Army's 350,000 US gallons (1,300,000 l). Meanwhile, as the distances increased the difficulty involved in delivering POL steadily mounted. The Third Army began rationing MT80. On 28 August, the Third Army reported that receipts had fallen 97,510 US gallons (369,100 l) short of its 450,000 US gallons (1,700,000 l) requirements. Deliveries fell to 31,975 US gallons (121,040 l) on 30 August, and 25,390 US gallons (96,100 l) on 2 September. One additional source was captured fuel; 115,000 US gallons (440,000 l) was captured at Châlons-du-Maine on 29 and 30 August, and the Third Army made use of 500,000 US gallons (1,900,000 l) during the pursuit. It also commandeered the fuel that Red Ball trucks needed for their return journeys, leaving convoys stranded. Yet at no stage was fuel actually in short supply; on 19 August the depots in Normandy held 27,000,000 US gallons (100,000,000 l) of gasoline, equivalent to twelve days of supply. The problem was one of distribution.[120]

The preferred method of moving bulk POL was through pipelines. Although Cherbourg's cargo-handling facilities had been damaged or destroyed, its POL-handling facilities were largely intact. The 5,000,000-US-barrel (600,000,000 l) of storage tanks were cleaned and put to allow them to hold MT80 instead of fuel oil. It took four weeks for the Navy to clear away the underwater obstacles and put the Digue de Quequerville, which had been the largest POL offloading point in the continent before the war, back into operation. The first elements of the Major System were installed in the form of 6-inch (15 cm), 8-inch (20 cm) and 12-inch (30 cm) pipelines from the Digue de Quequerville to the storage tanks.[99] Cherbourg handled its first POL on 26 July, and the Major System pipeline commenced operation six weeks behind schedule. On 31 July it reached La Haye-du-Puits, where two 15,000-US-barrel (1,800,000 l) storage tanks were erected.[98][99] Originally, it was supposed to head south to Avranches and then to Rennes in support of operations in Brittany, but as a result of Bradley's 3 August decision, the pipeline was directed southeastward to Saint-Lô, which was reached on 11 August.[121][122] A decanting point was opened at La Haye-du-Puits on 1 August that was manned by three gasoline supply companies and a service company that decanted 250,000 US gallons (950,000 l) per day.[123] On 19 August, when ADSEC turned them over to the Normandy Base Section, there were ten POL dumps and five decanting points.[124]

A workforce of over 7,200 troops and 1,500 prisoners of war was engaged in the construction of the Major System pipeline. Units involved included the 358th, 359th and 368th Engineer General Service Regiments and a battalion of the 364th Engineer General Service Regiment, and nine petroleum distribution companies. Through lack of experience, the engineers were sometimes careless with the couplings or left gaps that permitted the entry or animals or into which troops threw C-ration cans. In the attempt to push the pipeline ahead as quickly as possible, the engineers did not always take the time to break through hedgerows or clear minefields, and lines were often laid along road shoulders, where they were subject to damage by motor vehicles. The line was also subject to acts of sabotage, and black marketeers sometimes punched holes in it in order to steal fuel. Breaks in the line on 29 August forced truck units to draw MT80 from Saint-Lô, 80 miles (130 km) further away. Up to this point the pipeline had overriding priority, but its construction required the railway system to deliver 500 to 1,500 long tons (510 to 1,520 t) of pipes, tanks, pumps and fittings each day. By the end of August, one Major System MT80 pipeline had reached Alençon, another was at Domfront, and an MT100 pipeline had nearly reached Domfront. By mid-September, the pipeline's priority was downgraded, and it had to rely on motor transport, limiting progress to 7 to 8 miles (11 to 13 km) per day. The pipeline reached Coubert on 6 October, and there it remained until January 1945.[125][126]

The COMZ salvage effort was concentrated under the 202nd Quartermaster Battalion, which had three collecting and three repair companies. Combat units collected their own salvage, which was picked up at the truckheads and hauled to the salvage depots in returning ration trucks. The repair companies were static, but had mobile equipment maintenance units that visited the forward areas. The collecting companies combed the rear areas looking for abandoned equipment.[127] By August, a shortage of jerricans had become a critical supply problem.[128] Over 2 million jerricans had been discarded in Normandy.[124] Major General Robert McG. Littlejohn, the Chief Quartermaster, noted that the salvage companies and gasoline supply companies were ignoring the thousands of jerricans that littered the roads in the Le Mans area until he specifically ordered them to collect them. An even greater problem was the huge stockpiles of empty jerricans that had been abandoned at dumps when the units manning them had displaced forward.[128]

Littlejohn appointed Colonel Lyman R. Talbot, the chief the COMZ Petroleum and Fuel Division, as his special POL liaison officer at ADSEC,[124] with special responsibility for collecting jerricans. Since it was easier to move bulk POL to the jerrican dumps than to move the empty jerricans to the bulk POL, Littlejohn and Talbot established temporary filling points at the disused dumps.[128] Editorials urging that discarded cans be handed in were run in Stars and Stripes, the United States Information Service ran appeals in the news media, and French civilians, including children, were employed in the search for discarded jerricans. By the end of December, over one million discarded or abandoned jerricans had been recovered.[129]

Efforts were made to procure more jerricans. The War Office agreed to supply 221,000 per month, about half what Littlejohn estimated was required. Orders were placed in the United States, but production there had ceased, and efforts to restart it were hampered by a shortage of manpower. Shipping was also a problem, as the tonnage allocated to quartermaster items had been reduced, and Littlejohn needed shipping space for winter clothing. Jerricans had to be sent as filler or deck cargo. The number of decanting sites was reduced to minimise the reserves of cans. Finally, due to the shortage of jerricans, each army was forced to accept part of its POL allocation in bulk, or in 55-US-gallon (210 l) drums. These weighed 412 pounds (187 kg) when filled with gasoline, and were disliked by the combat troops, who had little access to handling equipment at their forward dumps, and the regarded them as inconvenient and dangerous.[129]

Railways

The Overlord planners intended to use rail transport for most long-distance haulage. France had a good rail network, with nearly 36,500 miles (58,700 km) of single- and double-track lines. Like most European railway systems, the rolling stock was lightweight and loading and unloading facilities were limited, so rolling stock coming from the United States had to be specifically designed and built for the purpose of operating on the continent. Railway units were scheduled to arrive at Cherbourg, but the delay in capturing and then opening the port meant that the first units arrived over the beaches. The first rolling stock, two 150-horsepower (110 kW) diesel locomotives and some flatcars, arrived on LCTs that were unloaded over Utah Beach on 10 July. Later that month the seatrains USAT Seatrain Texas and USAT Seatrain Lakehurst began delivering rolling stock to Cherbourg. The port was still too badly damaged for them to be berthed, so they were unloaded in the stream, with rolling stock transferred to barges that were unloaded on the shore with the aid of mobile cranes. While the seatrains brought in the heavier equipment like locomotives and tank cars, most rolling stock arrived on LSTs fitted with rails. By 31 July, 1944, 48 diesel and steam locomotives and 184 railway cars had arrived from the United Kingdom, and another 100 steam locomotives, 1,641 freight cars, and 76 passenger cars had been captured. [130][131]

The commander of the 2nd Military Railway Service, Brigadier General Clarence L. Burpee, arrived in Normandy on 17 June, and by the end of July the 707th Railway Grand Division had the 720th, 728th and 729th Railway Operating Battalions and the 757th Shop Battalion operational.[132] French civilian railway workers were employed whenever possible. Railway operations commenced in early July. Major General Frank S. Ross, the ETO Chief of Transportation, rode the line from Cherbourg to Carentan in a jeep equipped with flanged wheels.[131] Immediately after Operation Cobra began, the 347th Engineer General Service Regiment was withdrawn from its work on the port of Cherbourg and set to work rehabilitating the railway lines, which had been badly damaged by the Allied Air Forces. It started by repairing the masonry bridge over the Vire River on the Saint-Lô line, constructing a timber trestle bridge to replace a missing span. At Coutances, it replaced a missing span of a viaduct bridge. Reconstruction of the marshalling yards at Saint-Lô was a major task, as they had been almost completely destroyed.[133]

On 12 August, the Third Army asked for the line to Le Mans to be opened, with 12,000 long tons (12,000 t) of ammunition and POL to be delivered over the next three days. The main line eastward from Vire to Argentan was still in German hands, and the one southward to Rennes and then eastward to Le Mans could not be restored quickly because major bridge reconstruction tasks were required at Pontaubault and Laval. Instead, a temporary route was found using a series of secondary line while the main line was being repaired. Even this required some major bridge reconstruction work, notably an 80-foot (24 m) single-track bridge at Saint-Hilaire-du-Harcouët. Elements of no less than eleven engineer general service regiments worked on the lines simultaneously. When Major General Cecil R. Moore, the ETO Chief Engineer flew over the Saint-Hilaire bridge site at 1800 on 15 August, he saw a sign on the ground in white cement that read: "Will finish at 2000." The first train loaded with POL left Folligny at 1900, crossed the bridge at around midnight, and, after many delays, rolled into Le Mans on 17 August. Thirty more trains followed at half-hour intervals. [134][135]

With only single-track lines in use, the lines between Avranches and Le Mans soon became congested, and a shortage of empty freight cars developed. The rail yards at Folligny and Le Mans were badly damaged, and considerable reconstruction work was required. Getting the main line east of Rennes in use required the repair of the bridge at Laval, which was completed by the end of the month. By mid-August, the main line to Argentan was in Allied hands, and reconstruction of that line was given a high priority, and it was in use by the end of the month. Beyond Chartres, the lines were badly damaged, as the Allied Air Forces had given particular attention to interdicting German lines of communications across the Seine. By the end of August, 18,000 men, including 5,000 prisoners of war, were working on railway reconstruction. An American train reached the rail yards at Batignolles in Paris on 30 August by using a circuitous route, but its use was initially restricted to hospital trains, engineer supplies, and civil affairs relief. Nearly all the Seine bridges had been destroyed, and from 4 September only two or three trains per day navigated the Paris bottleneck to points beyond. Dreux and Chartres remained the forward railheads of the First and Third Armies respectively.[136]

Beyond the Seine, the railway network was more extensive, and damage was much lighter, as in had not been the target of air attack nearly as much as the railways in the Normandy lodgement area, and the Germans had not had time to destroy them. The main problem was shortage of rolling stock. Transfer points were established in the Paris area where Red Ball supplies were transferred to railway cars, taking some of the burden off the hard-pressed motor transport resources. By mid-September, 3,400 miles (5,500 km) of track had been rehabilitated and over forty bridges had been rebuilt. Lines had been opened north of Paris to Namur and Liege in Belgium to support the First Army, and eastward to Verdun and Conflans-en-Jarnisy to support the Third Army. By mid-September, the railways were hauling 2,000,000 ton-miles per day, and rail tonnages north of the Seine averaged only 5,000 long tons (5,100 t) per day.[137]

Motor transport

With the railways and pipelines unable to keep up with the pace of the advance, the breakout and pursuit from Normandy placed a heavy burden on ADSEC's Motor Transport Brigade. Yet even before Operation Cobra began, COMZ estimated that there would be a shortage 127 truck companies by D plus 90.[138] This was a consequence of decisions made in the planning stages of Overlord. COMZ had estimated that 240 truck companies would be required, but only 160 were approved in November 1943.[139] The theater was only partly responsible for this. In peacetime, the vaunted American motor vehicle industry had only produced about 600 heavy-duty trucks (defined as 4-ton vehicles or greater) a month. In July 1943, the ASF ordered 67,000 to be produced in 1944. The Truman Committee considered this wasteful and unnecessarily reducing the number of civilian trucks that could be built. Despite the political pressure, the Army pressed on with the production program, but in January 1944, only 2,788 heavy-duty trucks came off the assembly lines.[140]

Ross wanted two-thirds of the ETO's requested 160 companies equipped with the 10-ton semi-trailer, which was especially suitable for long-distance haulage, with the rest equipped with 2½-ton 6x6 trucks for shorter inter-depot movements and clearance of railheads, but by the end of March 1944, ETO had only 66 10-ton semi-trailers instead of the 7,194 it had requested, and none of the 4,167 4- or 5-ton truck tractors. In April, the War Department attempted to meet the requirements by taking hundreds of trucks of miscellaneous types from the ASF, Army Ground Forces and Army Air Forces in the United States, and ASF diverted 1,750 4- and 5-ton truck tractors and 3,500 5-ton semi-trailers earmarked for the Ledo Road project in Burma to the ETO.[141]

The tardy delivery of vehicles affected the training of the personnel of motor transport units. As with many other service units, the ETO had been compelled to accept partially trained units in the hope of their being able to complete their training in the UK. The late arrival of vehicles meant that this training could not get under way until May 1944. In August 1943 the Transportation Corps requested that each truck company be allocated an additional 36 drivers, bringing them up to 96 per company, so there would be two per vehicle, allowing the trucks to be operated around the clock. ETOUSA disapproved this, which it regarded as unnecessary, but nonetheless the Transportation Corps had persisted, and in early 1944 Lee had approved the proposal.[142]

But by this time the War Department had established a troop ceiling for the ETO, and would not provide the additional personnel without corresponding cuts elsewhere, so the 5,600 men to provide an additional 40 drivers for 140 companies had to be obtained from other SOS units. Lee sternly warned that he would not countenance this being used as an excuse to rid units of undesirables. Whether this admonition worked is debatable, but insufficient numbers of personnel were provided, so in May 1944, fourteen African-American truck companies had their personnel transferred to other African-American units. The intention was to replace them with Caucasian personnel, but the numbers were not made available. Instead, two engineer general service regiments were temporarily converted to truck units. The cost of inadequate training of truck drivers would be paid in avoidable damage to vehicles through accidents and poor maintenance.[142]

On 10 August, two companies of 45-ton tank transporters were converted to cargo carriers. A few days later, the 55 truck companies equipped with 2½-ton 6x6 trucks were each given ten additional trucks, and three British truck companies were borrowed from the 21st Army Group. The situation became acute with the decision to continue the pursuit across the Seine. COMZ estimated that this would require 100,000 long tons (100,000 t) of supplies (excluding POL) to be delivered to the Chartres-Dreux area by 1 September. Of this, the railways could deliver only 18,000 long tons (18,000 t), leaving 82,000 long tons (83,000 t) to be hauled by the Motor Transport Brigade. It was immediately realized that this would require an extraordinary effort.[143]