Akhenaten

Akhenaten (pronounced /ˌækəˈnɑːtən/[8]), also spelled Echnaton,[9] Akhenaton,[3] Ikhnaton,[2] and Khuenaten[10][11] (Ancient Egyptian: ꜣḫ-n-jtn, meaning "Effective for the Aten"), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning circa 1353–1336[3] or 1351–1334 BC,[4] the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Before the fifth year of his reign, he was known as Amenhotep IV (Ancient Egyptian: jmn-ḥtp, meaning "Amun is satisfied," Hellenized as Amenophis IV).

| Akhenaten Amenhotep IV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amenophis IV, Naphurureya, Ikhnaton[1][2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Statue of Akhenaten in the early Amarna style | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1353–1336 BC[3] or 1351–1334 BC[4] (18th Dynasty of Egypt) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Amenhotep III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Smenkhkare | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Nefertiti Kiya An unidentified sister-wife (disputed) Tadukhipa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Smenkhkare? Meritaten Meketaten Ankhesenamun Neferneferuaten Tasherit Neferneferure Setepenre Tutankhamun (disputed) Ankhesenpaaten Tasherit? Meritaten Tasherit? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Amenhotep III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Tiye | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1336 or 1334 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Royal Tomb of Akhenaten, Amarna (original tomb) KV55 (disputed)[6][7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Akhetaten, Gempaaten | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Egyptian religion Atenism | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Akhenaten is noted for abandoning Egypt's traditional polytheistic religion and introducing Atenism, worship centered on the sun disc Aten. The views of Egyptologists differ whether Atenism should be considered as absolute monotheism, or whether it was monolatry, syncretism, or henotheism.[12][13] This culture shift away from traditional religion was not widely accepted. After his death, Akhenaten's monuments were dismantled and hidden, his statues were destroyed, and his name excluded from lists of rulers compiled by later pharaohs.[14] Traditional religious practice was gradually restored, notably under his close successor Tutankhamun, who changed his name from Tutankhaten early in his reign.[15] When some dozen years later rulers without clear rights of succession from the Eighteenth Dynasty founded a new dynasty, they discredited Akhenaten and his immediate successors, referring to Akhenaten himself as "the enemy" or "that criminal" in archival records.[16]

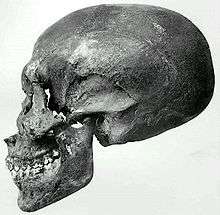

Akhenaten was all but lost to history until the late 19th century discovery of Amarna, or Akhetaten, the new capital city he built for the worship of Aten.[17] Furthermore, in 1907, a mummy that could be Akhenaten's was unearthed from the tomb KV55 in the Valley of the Kings by Edward R. Ayrton. Genetic testing has determined that the man buried in KV55 was Tutankhamun's father,[18] but its identification as Akhenaten has since been questioned.[6][7][19][20][21]

Akhenaten's rediscovery and Flinders Petrie's early excavations at Amarna sparked great public interest in the pharaoh and his queen Nefertiti. He has been described as "enigmatic," "mysterious," "revolutionary," "the greatest idealist of the world," and "the first individual in history," but also as a "heretic," "fanatic," "possibly insane," and "mad."[12][22][23][24][25] The interest comes from his connection with Tutankhamun, the unique style and high quality of the pictorial arts he patronized, and ongoing interest in the religion he attempted to establish.

Family

.jpg)

_(Mus%C3%A9e_du_Caire)_(2076972086).jpg)

The future Akhenaten was born Amenhotep, a younger son of pharaoh Amenhotep III and his principal wife Tiye. Crown prince Thutmose, Amenhotep III and Tiye's eldest son and Akhenaten's brother, was recognized as Amenhotep III's heir, but he died relatively young during his father's reign.[26] Following Thutmose's death, Akhenaten was the next in line for the throne.[27] Akhenaten also had four or five sisters, Sitamun, Henuttaneb, Iset or Isis, Nebetah, and possibly Beketaten.[28]

Akhenaten was married to Nefertiti, his Great Royal Wife; the exact timing of their marriage is unknown, but evidence from the king's building projects suggest that this happened either shortly before or after Akhenaten took Egypt's throne.[11] A secondary wife of Akhenaten named Kiya is known from inscriptions. Some have theorized that she gained her importance as the mother of Tutankhamen, Smenkhkare, or both. Some Egyptologists, such as William J. Murnane, proposed that Kiya is a colloqial name of the Mitanni princess Tadukhipa daughter of the Mitanni king Tushratta, widow of Amenhotep III and later wife of Akhenaten.[29][30] Akhenaten's other attested consorts are the daughter of Šatiya, ruler of Enišasi,[31] and a daughter of Burna-Buriash II, king of Babylonia.[31]

Seven or eight children are proposed based on inscriptions. Egyptologists are fairly certain about his six daughters, who are well attested in contemporary depictions.[32] Among his six daughters, Meritaten was born in regnal year one or five; Meketaten in year four or six; Ankhesenpaaten, later Queen of Tutankhamun, before year five or eight, Neferneferuaten Tasherit in year eight or nine; Neferneferure in year nine or ten; and Setepenre in year ten or eleven.[33][34][35][36] There is less certainty around his relationship with Smenkhkare, his successor, who could have been Akhenaten's son or daughter; he could have been Akhenaten's eldest son with an unknown wife, who later married Meritaten, his sister.[37] DNA analysis has revealed a mummy found in KV55 and the so-called "Younger Lady" mummy as children of Amunhotep III and Tiye as well as the parents of Tutankhaten, the later Tutankhamen.[38] The identification of the KV55 mummy with Akhenaten, however, remains highly controversial (see under Death, burial, and succession).

Some historians, such as Edward F. Wente and James Peter Allen, have proposed that Akhenaten took some of his daughters as wives or sexual consorts to father a male heir.[39][40] While this is debated, some historical parallels exist: Akhenaten's father Amenhotep III married his daughter Sitamun, while Ramesses II married two or more of his daughters, even though their marriages might simply have been ceremonial.[41][42] In Akhenaten's case, Meritaten, for example, recorded as Great Royal Wife to Smenkhkare, is also listed alongside pharaohs Akhenaten and Neferneferuaten as Great Royal Wife on a box from Tutankhamen's tomb. Letters written to Akhenaten from foreign rulers also make reference to Meritaten as "mistress of the house." Akhenaten might also have fathered a child with his daughter Meketaten. Meketaten's death, at perhaps the age of ten to twelve, is recorded in the Amarna royal tombs from around regnal years thirteen or fourteen. Early Egyptologists attributed her death possibly to childbirth, because of a depiction of an infant in her tomb. Because no husband is known for Meketaten, the assumption has been that Akhenaten was the father. Aidan Dodson believed this to be unlikely, as no Egyptian tomb has been found that mentions or alludes to the cause of death of the tomb owner, and Jacobus van Dijk proposed that the child is a portrayal of Meketaten's soul.[43] Finally, various monuments, originally for Kiya, were reinscribed for Akhenaten's daughters Meritaten and Ankhesenpaaten; the revised inscriptions list a Meritaten-tasherit ("junior") and an Ankhesenpaaten-tasherit. Some view this to indicate that Akhenaten fathered his own grandchildren. Others hold that, since these grandchildren are not attested to elsewhere, they are fictions invented to fill the space originally filled by Kiya's child.[44][39]

Early life

Egyptologists know very little about Akhenaten's life as prince. Egyptologist Donald B. Redford dated his birth before his father Amenhotep III's 25th regnal year, 1363–1361 BC, based on the birth of Akhenaten's first daughter, which likely happened fairly early in his own reign.[45][4] The only mention of his name, as "the King's Son Amenhotep," was found on a wine docket at his father Amenhotep III's palace at Malkata, where some historians suggest he was born. Others contend that he was born at Memphis, where growing up he was influenced by the worship of the sun god Ra practiced at nearby Heliopolis.[46]

Some historians have tried to determine who was Akhenaten's tutor during his youth, and have proposed scribes Heqareshu or Meryre II, the royal tutor Amenemotep, or the vizier Aperel.[47] The only person we know for certain served the prince was Parennefer, whose tomb mentions this fact.[48]

Egyptologist Cyril Aldred suggested that prince Amenhotep might have been a High Priest of Ptah in Memphis. It is known that Amenhotep's brother, crown prince Thutmose, served in this role before he died. If Amenhotep inherited his brother's roles in preparation for his accession to the throne, he might have become a high priest in Thutmose's stead. Aldred proposes that Akhenaten's unusual artistic inclinations might have been formed during his time serving Ptah, who was the patron god of craftsmen, and whose high priest were sometimes referred to as "The Greatest of the Directors of Craftsmanship."[49]

Reign

Coregency with Amenhotep III

There is much controversy around whether Amenhotep IV succeeded to the throne on the death of his father Amenhotep III or whether there was a coregency (lasting perhaps as long as 12 years). Eric Cline, Nicholas Reeves, Peter Dorman, and other scholars have argued strongly against the establishment of a long coregency between the two rulers and in favour of either no coregency or a brief one lasting at most two years.[50] Donald Redford, William Murnane, Alan Gardiner, and Lawrence Berman contest the view of any coregency whatsoever between Akhenaten and his father.[51]

Most recently, in 2014, archeologists found both pharaohs' names inscribed on the wall of the Luxor tomb of vizier Amenhotep-Huy. The Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities called this "conclusive evidence" that Akhenaten shared power with his father for at least 8 years, based on the dating of the tomb.[52] This conclusion has been called into question by other Egyptologists, according to whom the inscription only means that construction on Amenhotep-Huy's tomb commenced during Amenhotep III's reign and concluded under Akhenaten's, and Amenhotep-Huy thus simply wanted to pay his respects to both rulers.[53]

Early reign as Amenhotep IV

Akhenaten most likely took Egypt's throne in 1353[54] or 1351 BC.[4] It is unknown how old Akhenaten was when he did this; estimates range from 10 to 23.[55] He was most likely crowned in Thebes, or perhaps Memphis or Armant.[55]

The beginning of his reign followed established pharaonic traditions, as Amenhotep IV did not immediately start distancing himself from other gods and focusing solely on the Aten. According to Egyptologist Donald B. Redford, this implies that Akhenaten's eventual religious policies were not conceived well in advance and the pharaoh did not follow a pre-established plan or program. Redford points to three pieces of evidence to support this. First, surving inscriptions show Amenhotep IV worshipping several different gods, including Atum, Osiris, Anubis, Nekhbet, Hathor,[56] and the Eye of Ra, and texts from this era refer to "the gods" and "every god and every goddess." Second, even though he later moved his capital from Thebes to Akhetaten, his initial royal titulary honored Thebes (for example, his nomen was "Amenhotep, god-ruler of Thebes"), and recognizing its importance, he called Thebes "Southern Heliopolis, the first great (seat) of Re (or) the Disc." Third, his initial building program sought to build new places of worship to the Aten and did not destroy temples to the other gods.[57]

Indeed, the new pharaoh started a building program soon after his coronation. In Thebes, he decorated the southern entrance to the precincts of the temple of Amun-Re with scenes of him worshiping Re-Harakhti.

He also ordered the construction of temples or shrines to the Aten in several cities across the country, such as Bubastis, Tell el-Borg, Heliopolis, Memphis, Nekhen, Kawa, and Kerma.[58] However, the most significant temple decitated to the Aten was built at the Karnak Temple Complex in Thebes. This Temple of Amenhotep IV was called the Gempaaten ("The Aten is found in the estate of the Aten"). The Gempaaten consisted of a series of buildings, including a palace and a structure called the Hwt Benben (named after the Benben stone) which was dedicated to Queen Nefertiti. Other Aten temples constructed at Karnak during this time include the Rud-menu and the Teni-menu, which may have been constructed near the Ninth Pylon. During this time he did not repress the worship of Amun, and the High Priest of Amun was still active in the fourth year of his reign.[27] The king appears as Amenhotep IV in the tombs of some of the nobles in Thebes: Kheruef (TT192), Ramose (TT55) and the tomb of Parennefer (TT188).[59]

In the tomb of Ramose, Amenhotep IV appears on the west wall in the traditional style, seated on a throne with Ramose appearing before the king. On the other side of the doorway, Amenhotep IV and Nefertiti are shown in the window of appearance, with the Aten depicted as the sun disc. In the Theban tomb of Parennefer, Amenhotep IV and Nefertiti are seated on a throne with the sun disk depicted over the king and queen.[59]

In the first five or six years of his reign, perhaps in regnal year two or three, Amenhotep IV organized his first Sed festival. The exact reason for this is disputed. Sed festivals were celebrations of the pharaoh that usually took place for the first time around the thirtieth year of a pharaoh's reign and every three or so years thereafter. The celebrations were specifically aimed at the ritual rejuvenation of the aging pharaoh. There are only speculations as to why Amenhotep IV organized a Sed festival when he was likely still in his early twenties. Some historians see this as evidence of the coregency between Amenhotep III and Amenhotep IV, and that Amenhotep IV's Sed festival coincided with one of his father's celebrations. Others speculate that Amenhotep IV chose to hold his festival three years after his father's death, aiming to show his rule as a continuation of Amenhotep III's. Yet others believe that the festival was held in honor of the Aten on whose behalf the pharaoh ruled Egypt, or, as Amenhotep III was considered to have become one with the Aten following his death, the Sed festival honored both the pharaoh and the god at the same time. It is also possible that the purpose of the ceremony was to fill Amenhotep IV with strength before his great enterprise: the introduction of the Aten cult and the founding of the new capital at Amarna. Regardless of the true aim of the celebration, Egyptologists studying the surviving artistic impressions have concluded that during the festivities, the pharaoh only made offerings to the Aten rather than the many gods and goddesses, as customary.[49][60][61]

Among the discovered documents that refer to Akhenaten as Amenhotep IV the latest in his reign are two copies of a letter from Ipy, the high steward of Memphis, to the pharaoh. These letters, found in Gurob and informing the pharaoh that the royal estates in Memphis are "in good order" and the temple of Ptah is "prosperous and flourishing," are dated to regnal year five, day nineteen of the growing season's third month. About a month later, day thirteen of the growing season's fourth month, a boundary stone at Amarna already had the name Akhenaten carved on it, implying that Akhenaten changed his name during this timeframe.[62][63][64][65]

Name change

In regnal year five, Amenhotep IV decided to show his devotion to the Aten by changing his royal titulary. No longer would he be known as Amenhotep and be associated with the god Amun, but rather he would completely shift his focus to the Aten. Egyptologists debate the exact meaning of Akhenaten, his new personal name, as the term "akh" (Ancient Egyptian: ꜣḫ) could have different translations, such as "satisfied," "effective spirit," or "serviceable to," and thus Akhenaten's name could be translated to mean "Aten is satisfied," "Effective spirit of the Aten," or "Serviceable to the Aten," respectively.[66] Gertie Englund and Florence Friedman have arrived at the translation "effective for the Aten" by analyzing contemporary texts and inscriptions, in which Akhenaten often described himself as being "effective for" the sun disc. England and Friedman concluded that the frequency with which Akhenaten used this term likely means that his own name meant "Effective for the Aten."[66]

Some historians, such as Edel Elmar, Gerhard Fecht, and William F. Albright have proposed that Akhenaten's name is misspelled and mispronounced. These historians believe "Aten" should rather be "Jāti," thus rendering the pharaoh's name Akhenjāti (pronounced /ˌækəˈnjɑːtɪ/), as it could have been pronounced in Ancient Egypt.[67][68][69] Contemporaneously, the name would have been pronounced as Akhey-niyatnu.[69]

| Amenhotep IV | Akhenaten | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horus name | Kanakht-qai-Shuti "Strong Bull of the Double Plumes" |

Meryaten "Beloved of Aten" | |||||||||||||||||||

| Nebty name | Wer-nesut-em-Ipet-swt "Great of Kingship in Karnak" |

Wer-nesut-em-Akhetaten "Great of Kingship in Akhet-Aten" | |||||||||||||||||||

| Golden Horus name | Wetjes-khau-em-Iunu-Shemay "Crowned in Heliopolis of the South" (Thebes) |

Wetjes-ren-en-Aten "Exalter of the Name of Aten" | |||||||||||||||||||

| Prenomen | Neferkheperure-waenre "Beautiful are the Forms of Re, the Unique one of Re" | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Nomen | Amenhotep Netjer-Heqa-Waset "Amenhotep god-ruler of Thebes" |

Akhenaten "Effective for the Aten" | |||||||||||||||||||

Founding Amarna

Around the same time he changed his royal titulary, on the thirteenth day of the growing season's fourth month (around mid-April of the Gregorian calendar), Akhenaten decreed that a new capital city be built: Akhetaten (Ancient Egyptian: ꜣḫt-jtn, meaning "Horizon of the Aten"), better known today as Amarna. The event Egyptologists know the most about during Akhenaten's life are connected with founding Akhetaten, as numerous stele with surviving inscriptions have been found around the city to mark its boundary.[70] The pharaoh chose a site about halfway between Thebes, the capital at the time, and Memphis, on the east bank of Nile, where a wadi and a natural dip in the surrounding cliffs forms a silhouette similar to the "horizon" hieroglyph. Additionally, the site was previously uninhabited. On one of the stele, Akhenaten said that the site is appropriate for a city dedicated to the Aten because of this, for "not being the property of a god, nor being the property of a goddess, nor being the property of a ruler, nor being the property of a female ruler, nor being the property of any people able to lay claim to it."[71]

Historians do not know for certain why Akhenaten chose to build a new capital and leave the old capital of Thebes. The stele detailing the founding of Akhetaten is damaged where it explains Akhenaten's motives for the relocation. The parts that survive claim what happened to Akhenaten was "worse than those that I heard" previously in his reign and worse than those "heard by any kings who assumed the White Crown," and alludes to "offensive" speech to the Aten. Egyptologists believe that Akhenaten could be referring to conflict with the priesthood and followers of Amun, patron god of the capital Thebes. The great temples of Amun, such as Karnak, were all located in the capital of Thebes, and the priests achieved significant power earlier in the Eighteenth Dynasty, especially under Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, thanks to the pharaohs offering large amounts of Egypt's growing wealth to the cult of Amun; historians such as James Henry Breasted therefore posited that by moving to a new capital Akhenaten may have been trying to break with Amun's priests and their god.[72][73][74][75]

Akhetaten was a planned city with the Great Temple of the Aten, Small Aten Temple, royal residences, records office and government buildings in the city center. Some of these buildings, such as the Aten temples, were ordered to be built by Akhenaten on the stele announcing the city's founding.[74][76][77]

The city was built quickly, thanks to a new construction method that used substantially smaller stone blocks than under previous pharaohs. These blocks, called talatats, measured 1⁄2 by 1⁄2 by 1 ancient Egyptian cubits (c. 27 by 27 by 54 cm), and because of their small weight and standardized size, using them during constructions was more efficient than using heavy building blocks of varying sizes.[78][79] One year after decreeing a new capital city, in regnal year six, Akhenaten visited the city under construction to monitor progress. By regnal year eight, Akhetaten had reached a state where it could be occupied by the royal family. Not the entire Theban court, only his most loyal subjects followed Akhenaten and his family. While the city was being built, in years five through eight, construction work began to stop in Thebes: the Aten temples that had begun were not continued, and a village of workers working on the tombs of the Valley of the Kings was relocated to the workers' village of Akhetaten. However, construction work was continued in the rest of the country, as larger cult centers such as Heliopolis and Memphis also had temples built for Aton.[80][81]

International relations

The Amarna letters have provided important evidence about Akhenaten's reign and foreign policy. The letters are a cache of 382 diplomatic texts and literary and educational materials discovered between 1887 and 1979[82] and named after Amarna, the modern name for Akhenaten's capital Akhetaten. The diplomatic correspondence comprises of clay tablet messages between Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, and Tutankhamun, various subjects through Egyptian military outposts, rulers of vassal states, and the foreign rulers of Babylonia, Assyria, Syria, Canaan, Alashiya, Arzawa, Mitanni, and the Hittites.[83]

The Amarna letters portray the international situation in the Eastern Mediterranean that Akhenaten inherited from his predecessors. The kingdom's influence and military might increased greatly before starting to wane in the 200 years preceding Akhenaten's reign, following the expulsion of the Hyksos from Lower Egypt at the end of the Second Intermediate Period. Egypt's power reached new heights under Thutmose III, who ruled approximately 100 years before Akhenaten and led several successful military campaigns into Nubia and Syria. Egypt's expansion led to confrontation with the Mitanni, but this rivalry ended with the two nations becoming allies. Amenhotep III aimed to maintain the balance of power through marriages – such as his marriage to Tadukhipa, daughter of the Mitanni king Tushratta – and vassal states. Yet under Amenhotep III and Akhenaten, Egypt was unable or unwilling to oppose the rise of the Hittites around Syria. The pharaohs seemed to eschew military confrontation at a time when the balance of power between Egypt's neighbors and rivals was shifting, and the Hittites, a confrontational state, overtook the Mitanni in influence.[84][85][86][87]

Early in his reign, Akhenaten had conflicts with Tushratta, the king of Mitanni, who had courted favor with his father against the Hittites. Tushratta complains in numerous letters that Akhenaten had sent him gold-plated statues rather than statues made of solid gold; the statues formed part of the bride-price which Tushratta received for letting his daughter Tadukhepa marry Amenhotep III and then later marry Akhenaten. An Amarna letter preserves a complaint by Tushratta to Akhenaten about the situation:

"I...asked your father Mimmureya for statues of solid cast gold, [...] and your father said, 'Don't talk of giving statues just of solid cast gold. I will give you ones made also of lapis lazuli. I will give you too, along with the statues, much additional gold and [other] goods beyond measure.' Every one of my messengers that were staying in Egypt saw the gold for the statues with their own eyes. [...] But my brother [i.e., Akhenaten] has not sent the solid [gold] statues that your father was going to send. You have sent plated ones of wood. Nor have you sent me the goods that your father was going to send me, but you have reduced [them] greatly. Yet there is nothing I know of in which I have failed my brother. [...] May my brother send me much gold. [...] In my brother's country gold is as plentiful as dust. May my brother cause me no distress. May he send me much gold in order that my brother [with the gold and m]any [good]s may honor me."[88]

While Akhenaten was certainly not a close friend of Tushratta, he was evidently concerned at the expanding power of the Hittite Empire under its powerful ruler Suppiluliuma I. A successful Hittite attack on Mitanni and its ruler Tushratta would have disrupted the entire international balance of power in the Ancient Middle East at a time when Egypt had made peace with Mitanni; this would cause some of Egypt's vassals to switch their allegiances to the Hittites, as time would prove. A group of Egypt's allies who attempted to rebel against the Hittites were captured, and wrote letters begging Akhenaten for troops, but he did not respond to most of their pleas. Evidence suggests that the troubles on the northern frontier led to difficulties in Canaan, particularly in a struggle for power between Labaya of Shechem and Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem, which required the pharaoh to intervene in the area by dispatching Medjay troops northwards. Akhenaten pointedly refused to save his vassal Rib-Hadda of Byblos – whose kingdom was being besieged by the expanding state of Amurru under Abdi-Ashirta and later Aziru, son of Abdi-Ashirta – despite Rib-Hadda's numerous pleas for help from the pharaoh. Rib-Hadda wrote a total of 60 letters to Akhenaten pleading for aid from the pharaoh. Akhenaten wearied of Rib-Hadda's constant correspondences and once told Rib-Hadda: "You are the one that writes to me more than all the (other) mayors" or Egyptian vassals in EA 124.[89] What Rib-Hadda did not comprehend was that the Egyptian king would not organize and dispatch an entire army north just to preserve the political status quo of several minor city states on the fringes of Egypt's Asiatic Empire.[90] Rib-Hadda would pay the ultimate price; his exile from Byblos due to a coup led by his brother Ilirabih is mentioned in one letter. When Rib-Hadda appealed in vain for aid from Akhenaten and then turned to Aziru, his sworn enemy, to place him back on the throne of his city, Aziru promptly had him dispatched to the king of Sidon, where Rib-Hadda was almost certainly executed.[91]

Several Egyptologist in the late 19th and 20th centuries interpretated the Amarna letters to mean that Akhenaten neglected foreign policy and Egypt's foreign territories in favor of his internal reforms. For example, Henry Hall believed Akhenaten "succeeded by his obstinate doctrinaire love of peace in causing far more misery in his world than half a dozen elderly militarists could have done,"[92] while James Henry Breasted said Akhenaten "was not fit to cope with a situation demanding an aggressive man of affairs and a skilled military leader."[93] Others noted that the Amarna letters counter the conventional view that Akhenaten neglected Egypt's foreign territories in favour of his internal reforms. For example, Norman de Garis Davies praised Akhenaten's emphasis on diplomacy over war, while James Baikie said that the fact "that there is no evidence of revolt within the borders of Egypt itself during the whole reign is surely ample proof that there was no such abandonment of his royal duties on the part of Akhenaten as has been assumed."[94][95] Indeed, several letters from Egyptian vassals notified the pharaoh that they have followed his instructions, implying that the pharaoh sent such instructions:

To the king, my lord, my god, my Sun, the Sun from the sky: Message of Yapahu, the ruler of Gazru, your servant, the dirt at your feet. I indeed prostrate myself at the feet of the king, my lord, my god, my Sun, the Sun from the sky, 7 times and 7 times, on the stomach and on the back. I am indeed guarding the place of the king, my lord, the Sun of the sky, where I am, and all the things the king, my lord, has written me, I am indeed carrying out – everything! Who am I, a dog, and what is my house, and what is my [...], and what is anything I have, that the orders of the king, my lord, the Sun from the sky, should not obey constantly?[96]

The Amarna letters also show that vassal states were told repeteadly to expect the arrival of the Egyptian military on their lands, and provide evidence that these troops were dispatched and arrived at their destination. Dozens of letters detail that Akhenaten – andd Amenhotep III – sent Egyptian and Nubian troops, armies, archers, chariots, horses, and ships.[97]

Additionally, when Rib-Hadda was killed at the instigation of Aziru,[91] Akhenaten sent an angry letter to Aziru containing a barely veiled accusation of outright treachery on the latter's part.[98] Akhenaten wrote:

[Y]ou acted delinquently by taking [Rib-Hadda] whose brother had cast him away at the gate, from his city. He was residing in Sidon and, following your own judgment, you gave him to [some] mayors. Were you ignorant of the treacherousness of the men? If you really are the king's servant, why did you not denounce him before the king, your lord, saying, "This mayor has written to me saying, 'Take me to yourself and get me into my city'"? And if you did act loyally, still all the things you wrote were not true. In fact, the king has reflected on them as follows, "Everything you have said is not friendly."

Now the king has heard as follows, "You are at peace with the ruler of Qidsa (Kadesh). The two of you take food and strong drink together." And it is true. Why do you act so? Why are you at peace with a ruler whom the king is fighting? And even if you did act loyally, you considered your own judgment, and his judgment did not count. You have paid no attention to the things that you did earlier. What happened to you among them that you are not on the side of the king, your lord? [...] [I]f you plot evil, treacherous things, then you, together with your entire family, shall die by the axe of the king. So perform your service for the king, your lord, and you will live. You yourself know that the king does not fail when he rages against all of Canaan. And when you wrote saying, 'May the king, my Lord, give me leave this year, and then I will go next year to the king, my Lord. If this is impossible, I will send my son in my place' – the king, your lord, let you off this year in accordance with what you said. Come yourself, or send your son [now], and you will see the king at whose sight all lands live.[99]

This letter shows that Akhenaten paid close attention to the affairs of his vassals in Canaan and Syria. Akhenaten commanded Aziru to come to Egypt and proceeded to detain him there for at least one year. In the end, Akhenaten was forced to release Aziru back to his homeland when the Hittites advanced southwards into Amki, thereby threatening Egypt's series of Asiatic vassal states, including Amurru.[100] Sometime after his return to Amurru, Aziru defected to the Hittite side with his kingdom.[101] While it is known from an Amarna letter by Rib-Hadda that the Hittites "seized all the countries that were vassals of the king of Mitanni."[102] Akhenaten managed to preserve Egypt's control over the core of her Near Eastern Empire (which consisted of present-day Israel as well as the Phoenician coast) while avoiding conflict with the increasingly powerful Hittite Empire of Suppiluliuma I. Only the Egyptian border province of Amurru in Syria around the Orontes river was permanently lost to the Hittites when its ruler Aziru defected to the Hittites.

Only one military campaign is known for certain under Akhenaten's reign. In his second or twelfth year,[103] Akhenaten ordered his Viceroy of Kush Tuthmose to lead a military expedition to quell a rebellion and raids on settlements on the Nile by Nubian nomadic tribes. The victory was commemorated on two stelae, one discovered at Amada and another at Buhen. Egyptologists differ on the size of the campaign: Wolfgang Helck considered it a small-scale police operation, while Alan Schulman considered it a "war of major proportions."[104][105][106]

Other Egyptologists suggested that Akhenaten could have waged war in Syria or the Levant, possibly against the Hittites. Cyril Aldred, based on Amarna letters describing Egyptian troop movements, proposed that Akhenaten launched an unsuccessful war around the city of Gezer, while Marc Gabolde argued for an unsuccessful campaign around Kadesh. Either of these could be the campaign referred to on Tutankhamun's Restoriation Stela: "if an army was sent to Djahy [southern Canaan and Syria] to broaden the boundaries of Egypt, no success of their cause came to pass."[107][108][109] John Coleman Darnell and Colleen Manassa also argued that Akhenaten fought with the Hittites for control of Kadesh, but was unsuccessful; the city was not recaptured until 60–70 years later, under Seti I.[110]

Later years

Egyptologists know little about the last five years of Akhenaten's reign, beginning in c. 1341[3] or 1339 BC.[4][111] These years are poorly attested and only a few pieces of contemporary evidence survive; the lack of clarity makes reconstructing the latter part of the pharaoh's reign "a daunting task" and a controversial and contested topic of discussion among Egyptologists.[112] Among the latest pieces of evidence is an inscription discovered in 2012. That year, it was announced that a Year 16 III Akhet day 15 inscription dated explicitly to Akhenaten's reign which mentions, in the same breath, the presence of a living Queen Nefertiti, was found in a limestone quarry at Deir el-Bersha just north of Amarna.[113][114] The text refers to a building project in Amarna, and establishes that Akhenaten and Nefertiti were still a royal couple just a year before Akhenaten's death.

Before the 2012 discovery of the Deir el-Bersha inscriptions, the last known fixed-date event in Akhenaten's reign was a royal reception in regnal year twelve, in which the pharaoh and the royal family received tributes and offerings from allied countries and vassal states at Akhetaten. Insriptions shows tributes from Nubia, the Land of Punt, Syria, the Kingdom of Hattusa, the islands in the Mediterranean Sea, and Libya. Egyptologists such as Aidan Dodson consider this year twelve celebration to be the zenith of Akhenaten's reign.[115]

Historians are uncertain about the reasons for the year twelve reception. Possibilities include the celebration of the marriage of future pharaoh Ay to Tey, celebration of Akhenaten's twelve years on the throne, the summons of king Aziru of Amurru to Egypt, a military victory at Sumur in the Levant, a successful military campaign in Nubia,[116] Nefertiti's ascendancy to the throne as co-regent, or the completion of the new capital city Akhetaten.[117] However, thanks to reliefs in the tomb of courtier Meryre II, historians know that the royal family, Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and their six daughters, were present at the royal reception in full.[115]

Following year twelve, Donald B. Redford proposed that Egypt was struck by an epidemic, most likely a plague.[118] Contemporary evidence suggests that a plague ravaged through the Middle East around this time,[119] and Egyptologists suggested that ambassadors and delegations arriving to the pharaoh's year twelve reception might have brought the disease to Egypt.[120] Alternatively, letters from the Hattians suggested that the epidemic originated in Egypt and was carried throughout the Middle East by Egyptian prisoners of war.[121] Regardless of its origin, the epidemic might account for several deaths in the royal family that occurred in the last five years of Akhenaten's reigh, including those of his daughters Meketaten, Neferneferure, and Setepenre.[122][123][124]

Whether Smenkhkare became co-regent perhaps two or three years earlier or enjoyed a brief independent reign is unclear.[125] If Smenkhkare outlived Akhenaten, and became sole pharaoh, he likely ruled Egypt for less than a year. The next successor was Neferneferuaten, a female pharaoh who reigned in Egypt for two years and one month.[126] She was, in turn, probably succeeded by Tutankhaten (later, Tutankhamun), with the country being administered by the chief vizier, and future pharaoh, Ay. Tutankhamun was believed to be a younger brother of Smenkhkare and a son of Akhenaten, and possibly Kiya although one scholar has suggested that Tutankhamun may have been a son of Smenkhkare instead. DNA tests in 2010 indicated Tutankhamun was indeed the son of Akhenaten.[127] It has been suggested that after the death of Akhenaten, Nefertiti reigned with the name of Neferneferuaten[128] but other scholars believe this female ruler was rather Meritaten. The so-called Coregency Stela, found in a tomb in Amarna possibly shows his queen Nefertiti as his coregent, ruling alongside him, but this is not certain as the names have been removed and recarved to show Ankhesenpaaten and Neferneferuaten.[129]

Death, burial, and succession

.jpg)

Akhenaten was initially buried in the Royal Tomb of Amarna, located in the Royal Wadi east of Akhetaten. The order to construct the tomb and to bury the pharaoh there was commemorated on the Boundary Stelae deliniating the his capital city's borders: "Let a tomb be made for me in the eastern mountain [of Akhetaten]. Let my burial be made in it, in the millions of jubilees which the Aten, my father, decreed for me."[130] His sarcophagus was destroyed and remained in the Amarna necropolis; reconstructed, it is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo as of 2019.[131] After Tutankhamun abandoned Amarna and returned to Thebes, Akhenaten's mummy was removed from the Amarna tombs and moved to tomb KV55 in Valley of the Kings near Thebes.[132][133] This tomb was later desecreated, likely during the Ramesside period.[134][135]

Egyptologists believe that Akhenaten was most likely succeeded by Smenkhkare, who might have been Akhenaten's coregent for up to the last five years of Akhenaten's reign.[136][137] Smenkhkare's relationship with Akhenaten is uncertain; he could have been the son of Akhatentan or his brother, as the son of Amenhotep III with Tiye or Sitamun.[138] Archeological evidence makes it clear, however, that Smenkhkare was married to Meritaten, Akhenaten's eldest daughter.[139]

Recent genetic tests have confirmed that the body found buried in tomb KV55 was the father of Tutankhamun.[140] While the author of this paper conclude that he was therefore "most probably" Akhenaten, a number of experts disagree with this assessment, citing the young age at death as evidence.[21][141][142][143][144] The identity of the KV55 mummy continues to be controversial.

Legacy

With Akhenaten's death, the Aten cult he had founded fell out of favor: at first gradually, and then with decisive finality. Tutankhaten changed his name to Tutankhamun in Year 2 of his reign (c. 1332 BC) and abandoned the city of Akhetaten.[145] Their successors then attempted to erase Akhenaten and his family from the historical record. During the reign of Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty and the first pharaoh after Akhenaten who was not related to Akhenaten's family, Egyptians started to destroy temples to the Aten and reuse the building blocks in new construction projects, including in temples for the newly restored god Amun. Horemheb's successor continued in this effort. Seti I restored monuments to Amun and had the god's name re-carved on inscriptions where it was removed by Akhenaten. Seti I also ordered that Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, Neferneferuaten, Tutankhamun, and Ay be excised from official lists of pharaohs to make it appear that Amenhotep III was immediately succeeded by Horemheb. Under the Ramessides, who succeeded Seti I, Akhetaten was gradually destroyed and the building material reused across the country, such as in constructions at Hermopolis. The negative attitudes toward Akhenaten were illustrated by, for example, inscriptions in the tomb of scribe Mose (or Mes), where Akhenaten's reign is referred to as "the time of the enemy of Akhet-Aten."[146][147][148]

Some Egyptologists, such as Jacobus van Dijk and Jan Assmann, believe that Akhenaten's reign and the Amarna period started a gradual decline in the Egyptian government's power and the pharaoh's standing in Egyptian's society and religious life.[149][150] Akhenaten's religious reforms subverted the relationship ordinary Egyptians had with their gods and their pharaoh, as well as the role the pharaoh played in the relationship between the people and the gods. Before the Amarna period, the pharaoh was the representative of the gods on Earth, the son of the god Ra, and the living incarnation of the god Horus, and maintained the divine order through rituals and offerings and by sustaining the temples of the gods.[151] Additionally, even though the pharaoh oversaw all religious activity, Egyptians could access their gods through regular public holidays, festivals, and processions. This led to a seemingly close connection between people and the gods, especially the patron deity of their respective towns and cities.[152] Akhenaten, however, banned the worship of gods beside the Aten, including through festivals. He also declared himself to be the only one who could worship the Aten, and required that all religious devotion previously exhibited toward the gods be directed toward himself. After the Amarna period, during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties – c. 270 years following Akhenaten's death – the relationship between the people, the pharaoh, and the gods did not simply revert to pre-Amarna practices and beliefs. The worship of all gods returned, but the relationship between the gods and the worshipers became more direct and personal,[153] circumventing the pharaoh. Rather than acting through the pharaoh, Egyptians started to believe that the gods intervened directly in their lives, protecting the pious and punishing criminals.[154] The gods replaced the pharaoh as their own representatives on Earth. The god Amun once again became king among all gods.[155] According to van Dijk, "the king was no longer a god, but god himself had become king. Once Amun had been recognized as the true king, the political power of the earthly rulers could be reduced to a minimum."[156] Consequently, the influence and power of the Amun priesthood continued to grow until the Twenty-first Dynasty, c. 1077 BC, by which time the High Priests of Amun effectively became rulers over parts of Egypt.[157][150][158]

Atenism

_to_the_figure._Reign_of_Akhenaten._From_Amarna%2C_Egypt._The_Petrie_Museum_of_Egyptian_Archaeology%2C_London.jpg)

Solar worship had been growing in popularity even before Akhenaten, especially during the Eighteenth Dynasty and the reign of Amenhotep III, Akhenaten's father. During the New Kingdom, the pharaoh started to be associated with the sun disc; for example, one inscriptions called the pharaoh Hatshepsut the "female Re shining like the Disc," while Amenhotep III was described as "he who rises over every foreign land, Nebmare, the dazzling disc."[159] During the Eighteenth Dynasty, a religious hymn to the sun also appeared and became popular among Egyptians.[160] However, Egyptologists have questioned whether there is a causal relationship between the cult of the sun disc before Akhenaten and Akhenaten's religious policies.[160]

Implementation and development

The implementation of Atenism can be traced through gradual changes in the Aten's iconography, and Egyptologist Donald B. Redford divided its development into three stages, earliest, intermediate, and final, in his studies of Akhenaten and Atenism. The earliest stage was associated with a growing number of depictions of the sun disc, though the disc is still seen resting on the head of the god Ra-Horakhty. The intermediate stage was marked by the elevation of the Aten above other gods and the appearance of cartouches around his name in inscriptions—cartouches traditionally indicating that the enclosed text is a royal name. The final stage had the Aten represented as a sun disc with sunrays terminating in human hands and the introduction of a new epithet for the god: "the great living Disc which is in jubilee, lord of heaven and earth."[161]

In the early years of his reign, Amenhotep IV lived at Thebes with Nefertiti and his six daughters. Initially, he permitted worship of Egypt's traditional deities to continue but near the Temple of Karnak (Amun-Ra's great cult center), he erected several massive buildings including temples to the Aten. Aten was usually depicted as a sun disk with rays extending with long arms and tiny human hands at each end.[162] These buildings at Thebes were later dismantled by his successors and used as infill for new constructions in the Temple of Karnak; when they were later dismantled by archaeologists, some 36,000 decorated blocks from the original Aton building here were revealed which preserve many elements of the original relief scenes and inscriptions.[163]

One of the most important turning points in the early reign of Amenhotep IV is a speech given by the pharaoh at the beginning of his second regnal year. A copy of the speech survives on one of the pylons at the Karnak Temple Complex near Thebes. Speaking to the royal court, scribes or the people, Amenhotep IV said that the gods were ineffective and had ceased their movements, and that their temples had collapsed. The pharaoh contrasted this with the only remaining god, the sun disc Aten, who continued to move and exist forever. Some Egyptologists, such as Donald B. Redford, compared this speech to a proclamation or manifesto, which foreshadowed and explained the pharaoh's later religious reforms centered around the Aten.[164][165][166] In his speech, Akhenaten said:

The temples of the gods fallen to ruin, their bodies do not endure. Since the time of the ancestors, it is the wise man that knows these things. Behold, I, the king, am speaking so that I might inform you concerning the appearances of the gods. I know their temples, and I am versed in the writings, specficially, the inventory of their primeval bodies. And I have watched as they [the gods] have ceased their appearances, one after the other. All of them have stopped, except the god who gave birth to himself. And no one knows the mystery of how he performs his tasks. This god goes where he pleases and no one else knows his going. I approach him, the things which he has made. How exalted they are.[167]

In Year five of his reign, Amenhotep IV took decisive steps to establish the Aten as the sole god of Egypt: the pharaoh "disbanded the priesthoods of all the other gods...and diverted the income from these [other] cults to support the Aten". To emphasize his complete allegiance to the Aten, the king officially changed his name from Amenhotep IV to Akhenaten or 'Living Spirit of Aten.'[163] Akhenaten's fifth year also marked the beginning of construction on his new capital, Akhetaten or 'Horizon of Aten', at the site known today as Amarna. Very soon afterwards, he centralized Egyptian religious practices in Akhetaten, though construction of the city seems to have continued for several more years. In honor of Aten, Akhenaten also oversaw the construction of some of the most massive temple complexes in ancient Egypt. In these new temples, Aten was worshipped in the open sunlight rather than in dark temple enclosures as had been the previous custom. Akhenaten is also believed to have composed the Great Hymn to the Aten.

Initially, Akhenaten presented Aten as a variant of the familiar supreme deity Amun-Re (itself the result of an earlier rise to prominence of the cult of Amun, resulting in Amun's becoming merged with the sun god Ra), in an attempt to put his ideas in a familiar Egyptian religious context. However, by Year nice of his reign, Akhenaten declared that Aten was not merely the supreme god, but the only worshipable god, and that he, Akhenaten, was the only intermediary between Aten and his people. He ordered the defacing of Amun's temples throughout Egypt and, in a number of instances, inscriptions of the plural 'gods' were also removed.[168][169] This emphasized the changes encouraged by the new regime, which included a ban on images, with the exception of a rayed solar disc, in which the rays (commonly depicted ending in hands) appear to represent the unseen spirit of Aten, who by then was evidently considered not merely a sun god, but rather a universal deity. Representations of the Aten were always accompanied with a sort of hieroglyphic footnote, stating that the representation of the sun as all-encompassing creator was to be taken as just that: a representation of something that, by its very nature as something transcending creation, cannot be fully or adequately represented by any one part of that creation.[170]

Aten's name was also written differently starting around regnal year nine – or as early as year eight or as late as year fourteen, according to some historians.[171] From "Living Re-Horakhty, who rejoices in the horizon in his name Shu-Re who is in Aten," the god's name became "Living Re, ruler of the horizon, who rejoices in his name of Re the father who has returned as Aten," removing the Aten's connection to Shu and Re-Horakhty, two other gods.[172]

Atenism and other gods

Some debate has focused on the extent to which Akhenaten forced his religious reforms on his people.[173] Certainly, as time drew on, he revised the names of the Aten, and other religious language, to increasingly exclude references to other gods; at some point, also, he embarked on the wide-scale erasure of traditional gods' names, especially those of Amun.[174] Some of his court changed their names to remove them from the patronage of other gods and place them under that of Aten (or Ra, with whom Akhenaten equated the Aten). Yet, even at Amarna itself, some courtiers kept such names as Ahmose ("child of the moon god", the owner of tomb 3), and the sculptor's workshop where the famous Nefertiti Bust and other works of royal portraiture were found is associated with an artist known to have been called Thutmose ("child of Thoth"). An overwhelmingly large number of faience amulets at Amarna also show that talismans of the household-and-childbirth gods Bes and Taweret, the eye of Horus, and amulets of other traditional deities, were openly worn by its citizens. Indeed, a cache of royal jewelry found buried near the Amarna royal tombs (now in the National Museum of Scotland) includes a finger ring referring to Mut, the wife of Amun. Such evidence suggests that though Akhenaten shifted funding away from traditional temples, his policies were fairly tolerant until some point, perhaps a particular event as yet unknown, toward the end of the reign.[175]

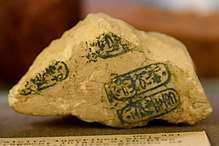

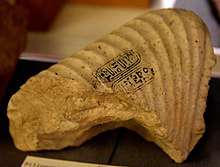

Archaeological discoveries at Akhetaten show that many ordinary residents of this city chose to gouge or chisel out all references to the god Amun on even minor personal items that they owned, such as commemorative scarabs or make-up pots, perhaps for fear of being accused of having Amunist sympathies. References to Amenhotep III, Akhenaten's father, were partly erased since they contained the traditional Amun form of his name: Nebmaatre Amunhotep.[176]

Following Akhenaten's death

As the Egytologist Nicholas Reeves wrote:

Such displays of frightening self-censorship and toadying loyalty are ominous indicators of the paranoia which was beginning to grip the country. Not only were the streets [of Akhetaten] filled with the pharaoh's soldiers; it seems the population now had to contend with the danger of malicious informers.[176]

In the end, Akhenaten's revolution collapsed from within after his death since the massive costs of founding a new capital city at El-Amarna and the closing of the Amun temples choked off the growth of the Egyptian economy. A notable result of Akhenaten's centralisation tendencies was the appearance of large-scale corruption among the king's state officials who held unprecedented control over all the wealth and produce of Egypt. This was a tendency that the last Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Horemheb was compelled to deal with by threatening to cut off the nose of any officials who were found to be involved in state corruption or abuses in a major stela erected near the 10th pylon of Karnak.[177] Nicolas Grimal stated that Akhenaten's closure or limitations on the activities of non-Aten temples and his confiscation of priestly goods for the benefit of the state directly led:

to an increase in centralization of both the administration and its executive arm, the army. The neglect of local government increased the problems of maintaining an effective administration and introduced a whole new [state] system characterized by corruption and arbitrariness... The construction of the new capital [at Akhetaten] and new temples was to the detriment of the economy in general and the temple-based economy in particular: the system of divine estates was, from a centralizing viewpoint, harmful, but its abandonment in the Amarna period led to the ruination of a whole [economic] system of production and distribution without providing any new structure to replace it.[178]

Artistic depictions

Styles of art that flourished during the reigns of Akhenaten and his immediate successors are markedly different from the traditional art of ancient Egypt. In many cases, representations are more realistic or naturalistic,[179] especially in depictions of animals and plants, and convey more action and movement for both non-royal and royal individuals than the traditionally static representations.[180][181][182]

The portrayals of Akhenaten himself greatly differ from the depictions of other pharaohs. Traditionally, the portrayal of pharaohs – and the Egyptian ruling class – was idealized, and they were shown in "stereotypically 'beautiful' fashion" as youthful and athletic.[183] However, Akhenaten's portrayals are unconventional and "unflattering" with a sagging stomach; broad hips; thin legs; thick thighs; large, "almost feminine breasts;" a thin, "exaggeratedly long face;" and thick lips.[184]

Based on Akhenaten's and his family's unusual artistic representations, including potential depictions of gynecomastia and androgyny, some have argued that the pharaoh and his family have either suffered from aromatase excess syndrome and sagittal craniosynostosis syndrome, or Antley–Bixler syndrome.[185] In 2010, results published from genetic studies on Akhenaten's purported mummy did not find signs of gynecomastia or Antley-Bixler syndrome,[18] although these results have since been questioned.[186]

Arguing instead for a symbolic interpretation, Dominic Montserrat in Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt states that "there is now a broad consensus among Egyptologists that the exaggerated forms of Akhenaten's physical portrayal... are not to be read literally".[187][176] Because the god Aten was referred to as "the mother and father of all humankind," Montserrat and others suggest that Akhenaten was made to look androgynous in artwork as a symbol of the androgyny of the god. This required "a symbolic gathering of all the attributes of the creator god into the physical body of the king himself", which will "display on earth the Aten's multiple life-giving functions".[187] Akhenaten claimed the title "The Unique One of Re", and he may have directed his artists to contrast him with the common people through a radical departure from the idealized traditional pharaoh image.[187]

Depictions of other members of the court, especially members of the royal family, are also extremely stylized and exaggerated.[180] Significantly, and for the only time in the history of Egyptian royal art, Akhenaten's family are shown taking part in decidedly naturalistic activities, showing affection for each other, and being caught in mid-action;[188][189] in traditional art, a pharaoh's divine nature was expressed by repose, even immobility.[190]

Nefertiti also appears, both beside the king and alone, or with her daughters, in actions usually reserved for a pharaoh, such as "smiting the enemy," a traditional depiction of male pharaohs.[191] This suggests that she enjoyed unusual status for a queen. Early artistic representations of her tend to be indistinguishable from her husband's except by her regalia, but soon after the move to the new capital, Nefertiti begins to be depicted with features specific to her. Questions remain whether the beauty of Nefertiti is portraiture or idealism.[192]

Speculative theories

Akhenaten's status as a religious revolutionary has led to much speculation, ranging from scholarly hypotheses to non-academic fringe theories. Although some believe the religion he introduced was mostly monotheistic, many others see Akhenaten as a practitioner of an Aten monolatry,[193] as he did not actively deny the existence of other gods; he simply refrained from worshiping any but the Aten while expecting the people to worship not Aten but him.

Akhenaten and monotheism in Abrahamic religions

The idea that Akhenaten was the pioneer of a monotheistic religion that later became Judaism has been considered by various scholars.[194][195][196][197][198] One of the first to mention this was Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, in his book Moses and Monotheism.[194] Basing his arguments on his belief that the Exodus story was historical, Freud argued that Moses had been an Atenist priest who was forced to leave Egypt with his followers after Akhenaten's death. Freud argued that Akhenaten was striving to promote monotheism, something which the biblical Moses was able to achieve.[194] Following the publication of his book, the concept entered popular consciousness and serious research.[199][200]

Freud commented on the connection between Adonai, the Egyptian Aten and the Syrian divine name of Adonis as the primeval unity of languages between the factions;[194] in this he was following the argument of Egyptologist Arthur Weigall. Jan Assmann's opinion is that 'Aten' and 'Adonai' are not linguistically related.[201]

It is widely accepted that there are strong stylistic similarities between Akhenaten's Great Hymn to the Aten and the Biblical Psalm 104, though this form of writing was widespread in ancient Near Eastern hymnology both before and after the period.

Others have likened some aspects of Akhenaten's relationship with the Aten to the relationship, in Christian tradition, between Jesus Christ and God, particularly interpretations that emphasize a more monotheistic interpretation of Atenism than a henotheistic one. Donald B. Redford has noted that some have viewed Akhenaten as a harbinger of Jesus. "After all, Akhenaten did call himself the son of the sole god: 'Thine only son that came forth from thy body'."[202] James Henry Breasted likened him to Jesus,[203] Arthur Weigall saw him as a failed precursor of Christ and Thomas Mann saw him "as right on the way and yet not the right one for the way".[204]

Redford argued that while Akhenaten called himself the son of the Sun-Disc and acted as the chief mediator between god and creation, kings had claimed the same relationship and priestly role for thousands of years before Akhenaten's time. However Akhenaten's case may be different through the emphasis which he placed on the heavenly father and son relationship. Akhenaten described himself as being "thy son who came forth from thy limbs", "thy child", "the eternal son that came forth from the Sun-Disc", and "thine only son that came forth from thy body". The close relationship between father and son is such that only the king truly knows the heart of "his father", and in return his father listens to his son's prayers. He is his father's image on earth, and as Akhenaten is king on earth, his father is king in heaven. As high priest, prophet, king and divine he claimed the central position in the new religious system. Because only he knew his father's mind and will, Akhenaten alone could interpret that will for all mankind with true teaching coming only from him.[202]

Redford concluded:

Before much of the archaeological evidence from Thebes and from Tell el-Amarna became available, wishful thinking sometimes turned Akhenaten into a humane teacher of the true God, a mentor of Moses, a christlike figure, a philosopher before his time. But these imaginary creatures are now fading away as the historical reality gradually emerges. There is little or no evidence to support the notion that Akhenaten was a progenitor of the full-blown monotheism that we find in the Bible. The monotheism of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament had its own separate development – one that began more than half a millennium after the pharaoh's death.[205]

Possible illness

The unconventional portrayals of Akhenaten – different from the traditional athletic norm in the portrayal of pharaohs – have led Egyptologists in the 19th and 20th centuries to suppose that Akhenaten suffered some kind of genetic abnormality.[184] Various illnesses have been put forward, with Frölich's syndrome or Marfan syndrome being mentioned most commonly.[206]

Cyril Aldred,[207] following up earlier arguments of Grafton Elliot Smith[208] and James Strachey,[209] suggested that Akhenaten may have suffered from Frölich's syndrome on the basis of his long jaw and his feminine appearance. However, this is unlikely, because this disorder results in sterility and Akhenaten is known to have fathered numerous children. His children are repeatedly portrayed through years of archaeological and iconographic evidence.[210]

Burridge[211] suggested that Akhenaten may have suffered from Marfan syndrome, which, unlike Frölich's, does not result in mental impairment or sterility. Marfan sufferers tend towards tallness, with a long, thin face, elongated skull, overgrown ribs, a funnel or pigeon chest, a high curved or slightly cleft palate, and larger pelvis, with enlarged thighs and spindly calves, sympotns that appear in some depictions of Akhenaten.[212] Marfan syndrome is a dominant characteristic, which means sufferers have a 50% chance of passing it on to their children.[213] However, DNA tests on Tutankhamun in 2010 proved negative for Marfan syndrome.[38]

By the early 21st century, most Egyptologists argued that Akhenaten's portrayals are not the results of a genetic or medical condition, but rather should be interpreted through the lens of Atenism.[176][187] Akhenaten was made to look androgynous in artwork as a symbol of the androgyny of the Aten.[187]

In the arts

The life of Akhenaten has inspired many fictional representations.

On page, Thomas Mann made Akhenaten the "dreaming pharaoh" of Joseph's story in the fictional biblical tetraology Joseph and His Brothers from 1933–1943. Akhenaten appears in Mika Waltari's The Egyptian, first published in Finnish (Sinuhe egyptiläinen) in 1945, translated by Naomi Walford; David Stacton's On a Balcony from 1958; Gwendolyn MacEwen's King of Egypt, King of Dreams from 1971; Allen Drury's A God Against the Gods from 1976 and Return to Thebes from 1976; Naguib Mahfouz's Akhenaten, Dweller in Truth from 1985; Andree Chedid's Akhenaten and Nefertiti's Dream; and Moyra Caldecott's Akhenaten: Son of the Sun from 1989. Additionally, Pauline Gedge's 1984 novel The Twelfth Transforming is set in the reign of Akhenaten, details the construction of Akhetaten and includes accounts of his sexual relationships with Nefertiti, Tiye and successor Smenkhkare. Akhenaten inspired the poetry collection Akhenaten by Dorothy Porter. And in comic books, Akhenaten is the major antagonist in the 2008 comic book series (reprinted as a graphic novel) "Marvel: The End" by Jim Starlin and Al Milgrom. In this series, pharaoh gains unlimited power and, though his stated intentions are benevolent, is opposed by Thanos and essentially all of the other superheroes and supervillains in the Marvel comic book universe. Finally, Akhenaten provides much of the background in the comic book adventure story Blake et Mortimer: Le Mystère de la Grande Pyramide vol. 1+2 by Edgar P. Jacobs from 1950.

On stage, the 1937 play Akhnaton by Agatha Christie explores the lives of Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and Tutankhaten.[216] He was portrayed in the Greek play Pharaoh Akhenaton (Greek: Φαραώ Αχενατόν) by Angelos Prokopiou.[217] The pharaoh also inspired the 1983 opera Akhnaten by Philip Glass.

In film, Akhenaten is played by Michael Wilding in The Egyptian from 1954 and Amedeo Nazzari in Nefertiti, Queen of the Nile from 1961. In the 2007 animated film La Reine Soleil, Akhenaten, Tutankhaten, Akhesa (Ankhesenepaten, later Ankhesenamun), Nefertiti, and Horemheb are depicted in a complex struggle pitting the priests of Amun against Atenism. Akhenaten also appears in several documentaries, including The Lost Pharaoh: The Search for Akhenaten, a 1980 National Film Board of Canada documentary based on Donald Redford's excavation of one Akhenaten's temples,[215] and episodes of Ancient Aliens, which propose that Akhenaten may have been an extraterrestrial.[218]}

In video games, for example, Akhenaten is the enemy in the Assassin's Creed Origins "The Curse of the Pharaohs" DLC, and must be defeated to remove his curse on Thebes.[219] His afterlife takes the form of 'Aten', a location which draws heavily on the architecture of the city of Amarna. Additionally, a version of Akhenaten (incorporating elements of H.P. Lovecraft's Black Pharaoh) is the driving antagonist behind the Egypt chapters of The Secret World, where the player must stop a modern-day incarnation of the Atenist cult from unleashing the now-undead pharaoh and the influence of Aten (which is portrayed as a real and extremely powerful malevolent supernatural entity with the ability to strip followers of their free will) upon the world. He is explicitly stated to be the Pharaoh who opposed Moses in the Book of Exodus, diverging from the traditional Exodus narrative in that he retaliates against Moses's 10 Plagues with 10 plagues of his own before being sealed away by the combined forces of both Moses and Ptahmose, the High Priest of Amun. He is also shown to have been an anachronistic alliance with the Roman cult of Sol Invictus, who are strongly implied to be worshiping Aten under a different name.

In music, Akhenaten is the subject of several compositions, including the jazz album Akhenaten Suite by Roy Campbell, Jr.,[220] the symphony Akhenaten (Eidetic Images) by Gene Gutchë, the progressive metal song Cursing Akhenaten by After the Burial, and the technical death metal song Cast Down the Heretic by Nile.

Ancestry

| 16. Thutmose III | |||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Amenhotep II | |||||||||||||||||||

| 17. Merytre-Hatshepsut | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Thutmose IV | |||||||||||||||||||

| 9. Tiaa | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Amenhotep III | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Mutemwiya | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Akhenaten | |||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Yuya | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Tiye | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Tjuyu | |||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Pharaoh of the Exodus

- Osarseph

Notes and references

Notes

- Cohen & Westbrook 2002, p. 6.

- Rogers 1912, p. 252.

- Britannica.com 2012.

- von Beckerath 1997, p. 190.

- Leprohon 2013, pp. 104–105.

- Strouhal 2010, pp. 97–112.

- Duhig 2010, p. 114.

- Dictionary.com 2008.

- Montserrat 2003, p. 105, 111.

- Kitchen 2003, p. 486.

- Tyldesley 2005.

- Ridley 2019, p. 13-15.

- Hart 2000, p. 44.

- Manniche 2010, p. ix.

- Zaki 2008, p. 19.

- Trigger et al. 2001, p. 186-187.

- Hornung 1992, pp. 43-44.

- Hawass et al. 2010.

- Marchant 2011, pp. 404–06.

- Lorenzen & Willerslev 2010.

- Bickerstaffe 2010.

- Spence 2011.

- Sooke 2014.

- Hessler 2017.

- Silverman, Wegner & Wegner 2006, pp. 185–188.

- Dodson 1990, p. 88.

- Aldred 1991, pp. 259–268.

- Ridley 2019, p. 37-39.

- Tyldesley 2006, p. 124.

- Murnane 1995, p. 9, 90–93, 210–211.

- Grajetzki 2005.

- Dodson 2012, p. 1.

- Ridley 2019, p. 78.

- Laboury 2010, p. 314-322.

- Dodson 2009, p. 41-42.

- University College London 2001.

- Dodson 2009, p. 84-87.

- Schemm 2010.

- Harris & Wente 1980, pp. 137-140.

- Allen 2009, pp. 15–18.

- Ridley 2019, p. 257.

- Robins 1993, pp. 21–27.

- Dodson 2009, pp. 54–55.

- Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 154.

- Redford 2013, p. 13.

- Ridley 2019, p. 40–41.

- Laboury 2010, p. 81.

- Murnane 1995, p. 78.

- Aldred 1991, p. 259.

- Reeves 2019, p. 77.

- Berman 2004, p. 23.

- Martín Valentín & Bedman 2014.

- Brand 2020, pp. 63-64.

- Ridley 2019, p. 45.

- Ridley 2019, p. 46.

- Ridley 2019, p. 48.

- Redford 2013, pp. 13–14.

- Redford 2013, p. 19.

- Nims 1973, pp. 186–187.

- Desroches-Noblecourt 1963, pp. 144–145.

- Gohary 1992, pp. 29–39, 167–169.

- Murnane 1995, pp. 50–51.

- Ridley 2019, pp. 83–85.

- Hoffmeier 2015, p. 166.

- Murnane & Van Siclen III 2011, p. 150.

- Ridley 2019, p. 85–87.

- Albright 1946.

- Elmar 1948.

- Fecht 1960.

- Ridley 2019, p. 85.

- Dodson 2014, p. 180–185.

- Breasted 2001, p. 390.

- Dodson 2014, p. 186–188.

- Ridley 2019, p. 85–90.

- Redford 2013, pp. 9–10.

- Aldred 1991, p. 269-270.

- Breasted 2001, p. 390-400.

- Arnold 2003, p. 238.

- Shaw 2003, p. 274.

- Aldred 1991, pp. 269-273.

- Shaw 2003, pp. 293-297.

- Moran 1992, pp. xiii, xv.

- Moran 1992, p. xvi.

- Aldred 1991, chpt. 11.

- Moran 1992, pp. 87–89.

- Drioton & Vandier 1952, pp. 411–414.

- Ridley 2019, pp. 297, 314.

- Moran 1992, p. 87-89.

- Moran 1992, p. 203.

- Ross 1999, pp. 30–35.

- Bryce 1998, p. 186.

- Hall 1921, pp. 42–43.

- Breasted 1909, p. 355.

- Davies 1903–1908, part II. p. 42.

- Baikie 1926, p. 269.

- Moran 1992, pp. 368-369.

- Ridley 2019, pp. 316–317.

- Moran 1992, p. 248-250.

- Moran 1992, p. 248-249.

- Bryce 1998, p. 188.

- Bryce 1998, p. 189.

- Moran 1992, p. 145.

- Murnane 1995, pp. 55–56.

- Darnell & Manassa 2007, pp. 118–119.

- Ridley 2019, pp. 323–324.

- Schulman 1982.

- Murnane 1995, p. 99.

- Aldred 1968, p. 241.

- Gabolde 1998, pp. 195–205.

- Darnell & Manassa 2007, pp. 172–178.

- Ridley 2019, pp. 346–364.

- Ridley 2019, p. 346.

- Van der Perre 2012, p. 195–197.

- Van der Perre 2014, pp. 67–108.

- Dodson 2009, pp. 39–41.

- Darnell & Manassa 2007, p. 127.

- Ridley 2019, p. 141.

- Redford 1984, pp. 185–192.

- Braverman, Redford & Mackowiak 2009, p. 557.

- Dodson 2009, p. 49.

- Laroche 1971, p. 378.

- Gabolde 2011.

- Ridley 2019, p. 354.

- Ridley 2019, p. 376.

- Allen 2009, pp. 1–4.

- Hornung, Krauss & Warburton 2006, pp. 207, 493.

- Hawass et al. 2010, p. 641.

- Ridley 2019, p. 251.

- Allen 1988, pp. 117–126.

- Kemp 2015, p. 11.

- Ridley 2019, pp. 365–371.

- Dodson 2014, p. 244.

- Aldred 1968, pp. 140–162.

- Ridley 2019, pp. 411–412.

- Dodson 2009, p. 144–145.

- Dodson 2014, p. 144.

- Tyldesley 1998, pp. 160–175.

- Ridley 2019, pp. 337, 345.

- Ridley 2019, p. 252.

- Hawass et al. 2010, p. 644.

- Strouhal 2010.

- Marchant 2011.

- Duhig 2010.

- Rose 2010.

- Dodson 2014, pp. 245–249.

- Hoffmeier 2015, pp. 241-243.

- Ridley 2019, p. 415.

- Mark 2014.

- van Dijk 2003, p. 303.

- Assmann 2005, p. 44.

- Wilkinson 2003, p. 55.

- Reeves 2019, pp. 139, 181.

- Breasted 1972, pp. 344–370.

- Ockinga 2001, pp. 44–46.

- Wilkinson 2003, p. 94.

- van Dijk 2003, p. 307.

- van Dijk 2003, pp. 303–307.

- Kitchen 1986, p. 531.

- Sethe 1906–1909, pp. 19, 332, 1569.

- Redford 2013, p. 11.

- Redford 1976, pp. 53–56.

- Asante & Mazama 2009.

- David 1998, p. 125.

- Aldred 1991, pp. 261–262.

- Hoffmeier 2015, pp. 160–161.

- Redford 2013, p. 14.

- Perry 2019, 03:59.

- Ridley 2019, p. 188.

- Hart 2000, p. 42-46.

- Ridley 2019, pp. 211-213.

- Ridley 2019, pp. 28, 173–174.

- Dodson 2009, p. 38.

- Hornung 1992, p. 47.

- Allen 2005, pp. 217–221.

- Ridley 2019, p. 187–194.

- Reeves 2019, pp. 154–155.

- Breasted 2001, §§ 50–67.

- Grimal 1992, p. 232.

- Wolf 1951, p. 15.

- Baptista, Santamarina & Conant 2017.

- Breasted 1909, p. 225.

- Arnold 1996, p. viii.

- Sooke 2016.

- Takács & Cline 2015, pp. 5–6.

- Braverman, Redford & Mackowiak 2009.

- Braverman & Mackowiak 2010.

- Montserrat 2003.

- Aldred 1985, p. 174.

- Arnold 1996, p. 114.

- Van Dyke 1887, pp. 38–39.

- Arnold 1996, p. 85.

- Arnold 1996, pp. 85–86.

- Montserrat 2003, p. 36.

- Freud 1939.

- Stent 2002, pp. 34–38.

- Assmann 1997.

- Shupak 1995.

- Albright 1973.

- Chaney 2006, pp. 62-69.

- Chaney 2014.

- Assmann 1997, pp. 23–24.

- Redford 1987.

- Levenson 1994, p. 60.

- Hornung 2001, p. 14.

- Redford, Shanks & Meinhardt 1997.

- Ridley 2019, p. 87.

- Aldred 1991.

- Smith 1923, pp. 83–88.

- Strachey 1939.

- Hawass 2010.

- Burridge 1995.

- Lorenz 2010.

- National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences 2017.

- Khan Academy 2013.

- Kendall 1980.

- Christie 1973.

- Prokopiou 1993.

- History.com 2018.

- Assassin's Creed Origins 2018.

- Roy Campbell 2012.

Bibliography

- "Akhenaten". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on October 14, 2008. Retrieved October 2, 2008.

- Dorman, Peter F. "Akhenaton (King of Egypt)". Britannica.com. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- Albright, William Foxwell (1946). "Cuneiform Material for Egyptian Prosopography, 1500-1200 B.C.". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. The University of Chicago Press. 5 (1): 7–25. doi:10.1086/370767. ISSN 0022-2968. JSTOR 542452.

- Albright, William F. (1973). "From the Patriarchs to Moses II. Moses out of Egypt". The Biblical Archaeologist. 36 (2): 48–76. doi:10.2307/3211050. JSTOR 3211050.

- Aldred, Cyril (1968). Akhenaten, Pharaoh of Egypt: A New Study. New Aspects of Antiquity (1st ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500390047.

- Aldred, Cyril (1985) [1980]. Egyptian art in the Days of the Pharaohs 3100–32 BC. World of Art. London; New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20180-3. LCCN 84-51309.

- Aldred, Cyril (1991) [1988]. Akhenaten, King of Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0500276218.

- Allen, James Peter (1988). "Two Altered Inscriptions of the Late Amarna Period". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. San Antonio, Texas: American Research Center in Egypt. 25: 117–126. doi:10.2307/40000874. ISSN 0065-9991. JSTOR 40000874.