Aten

Aten also Aton, Atonu, Itn (Ancient Egyptian: jtn, reconstructed [ˈjaːtin]) was the focus of Atenism, the religious system established in ancient Egypt by the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten. The Aten was the disc of the sun and originally an aspect of Ra, the sun god in traditional ancient Egyptian religion, but Akhenaten made it the sole focus of official worship during his reign.

| Aten | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Aten | ||||

| Name in hieroglyphs | ||||

| Major cult center | Amarna | |||

| Symbol | Sun disc and reaching rays of light | |||

| Parents | none (self-created or un-created) | |||

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

Beliefs |

|

Practices

|

|

Deities (list) |

|

Locations |

|

Symbols and objects

|

|

Related religions

|

|

|

In his poem "Great Hymn to the Aten", Akhenaten praises Aten as the creator, giver of life, and nurturing spirit of the world. Aten does not have a creation myth or family but is mentioned in the Book of the Dead. The worship of Aten was eradicated by Horemheb.

Etymology and origin

The word "Aten" appears in the Old Kingdom as a noun meaning "disc" which referred to anything flat and circular; the sun was called the "disc of the day" where Ra was thought to reside. [1] By analogy, the term "silver aten" was sometimes used to refer to the moon.[2] High relief and low relief illustrations of the Aten show it with a curved surface, therefore, the late scholar Hugh Nibley insisted that a more correct translation would be globe, orb or sphere, rather than disk.[3]

The first known reference to Aten the sun-disk as a deity is in The Story of Sinuhe from the 12th dynasty,[4] in which the deceased king is described as rising as a god to the heavens and uniting with the sun-disk, the divine body merging with its maker.[5]

Religion

_to_the_figure._Reign_of_Akhenaten._From_Amarna%2C_Egypt._The_Petrie_Museum_of_Egyptian_Archaeology%2C_London.jpg)

The solar Aten was extensively worshipped as a god in the reign of Amenhotep III when it was depicted as a falcon-headed man much like Ra. In the reign of Amenhotep III's successor, Amenhotep IV, the Aten became the central god of the Egyptian state religion, and Amenhotep IV changed his name to Akhenaten to reflect his close link with the new supreme deity.[4] The principles of Aten's religion were recorded on the rock tomb walls of Akhetaten. In the religion of Aten (Atenism), night is a time to fear.[6] Work is done best when the sun, Aten, is present. Aten cares for every creature, and created a Nile river in the sky (rain) for the Syrians.[7] Aten created all countries and people. The rays of the sun disk only holds out life to the royal family; everyone else receives life from Akhenaten and Nefertiti in exchange for loyalty to Aten.[8] Aten is depicted caring for the people through Akhenaten by Aten's hands extending towards the royalty, giving them ankhs representing life being given to humanity through both Aten and Akhenaten. In Akhenaten's Hymn to Aten, a love for humanity and the Earth is depicted in Aten's mannerisms:

"Aten bends low, near the earth, to watch over his creation; he takes his place in the sky for the same purpose; he wearies himself in the service of the creatures; he shines for them all; he gives them sun and sends them rain. The unborn child and the baby chick are cared for; and Akhenaten asks his divine father to 'lift up' the creatures for his sake so that they might aspire to the condition of perfection of his father, Aten".[9]

Akhenaten represented himself not as a god, but as a son of Aten, shifting the previous methods of pharaohs claiming to be the embodiment of Horus. This contributes to the belief that Atenism should be considered a monotheistic religion where "the living Aten beside whom there is no other; he was the sole god".[1]

There is only one known instance of the Aten talking, "said by the 'Living Aten': my rays illuminate..."[10]

Aten is an evolution of the idea of a sun god in Egyptian mythology, deriving a lot of his concepts of power and representation from the earlier god Ra but building on top of the power Ra represents. Aten carried absolute power in the universe, representing the life-giving force of light to the world as well as merging with the concept and goddess Maat to develop further responsibilities for Aten beyond the power of light itself.[9]

Iconography

Aten, by nature, was everywhere and intangible because he was the sunlight and energy in the world. Therefore, he did not have physical representations that other Egyptian gods had; he was represented by the sun disc and reaching rays of light.[9] The explanation as to why Aten could not be fully represented was that Aten was beyond creation. Thus the scenes of gods carved in stone previously depicted animals and human forms, now showed Aten as an orb above with life-giving rays stretching toward the royal figure. This power transcended human or animal form.[11]

Worship

The cult centre of Aten was at the new city Akhetaten;[12] some other cult cities include Thebes and Heliopolis. The principles of Aten's cult were recorded on the rock walls of tombs of Amarna. Significantly different from other ancient Egyptian temples, temples of Aten were open-roofed to allow the rays of the sun. Doorways had broken lintels and raised thresholds. No statues of Aten were allowed; those were seen as idolatry.[13] However, these were typically replaced by functionally equivalent representations of Akhenaten and his family venerating the Aten and receiving the ankh (breath of life) from him. Priests had less to do since offerings (fruits, flowers, cakes) were limited, and oracles were not needed.[14]

In the worship of Aten, the daily service of purification, anointment, and clothing of the divine image was not performed. Incense was burnt several times a day. Hymns sung to Aten were accompanied by harp music. Aten's ceremonies in Akhetaten involved giving offerings to Aten with a swipe of the royal scepter. Instead of barque processions, the royal family rode on a chariot on festival days.Elite women were known to worship the Aten in sun-shade temples in Akhetaten.[15]

Architecture

Two temples were central to the city of Akhetaten, the larger of the two had an "open, unroofed structure covering an area of about 800 by 300 metres (2,600 ft × 1,000 ft) at the northern end of the city".[16] Temples to the Aten were open-air structures with little to no roofing to maximize the amount of sunlight on the interior making them unique compared to other Egyptian temples of the time. Balustrades depicting Akhenaten, the queen and the princess embracing the rays of Aten flanked stairwells, ramps, and altars. These fragments were initially identified as stele but were later reclassified as balustrades based on the presence of scenes on both sides.[17]

Royal Titulary

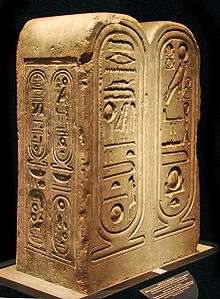

During the Amarna Period, the Aten was given a royal titulary enclosed in a double cartouche, carrying royal implications. Some have interpreted this to mean that Akhenaten was the embodiment of Aten, and the worship of Aten is directly worship of Akhenaten; but others have taken this as an indicator of Aten as the supreme ruler even over the current reigning royalty.[18][19]

There were two forms of the title; the first had the names of other gods, and the second later one was more 'singular' and referred only to the Aten himself. The early form was Re-Horakhti who rejoices in the Horizon, in his name Shu, which is the Aten. The later form was Re, ruler of the two horizons, who rejoices in the Horizon, in his name of light, which is the Aten.

Ra-Horus, more usually referred to as Ra-Horakhty (Ra, who is Horus of the two horizons), is a synthesis of two other gods, both of which are attested from very early on. During the Amarna period, this synthesis was seen as the invisible source of energy of the sun god, of which the visible manifestation was the Aten, the solar disk. Thus Ra-Horus-Aten was a development of old ideas which came gradually. The real change, as some see it, was the apparent abandonment of all other gods, especially Amun-Ra, prohibition of idolatry, and the debatable introduction of quasi-monotheism by Akhenaten.[20] The syncretism is readily apparent in the Great Hymn to the Aten in which Re-Herakhty, Shu and Aten are merged into the creator god.[21] Others see Akhenaten as a practitioner of an Aten monolatry,[22] as he did not actively deny the existence of other gods; he simply refrained from worshipping any but the Aten. Other scholars call the religion henotheistic.[23]

After Akhenaten

Akhenaten was considered the "high priest" or even a prophet of Aten, being the main propagator of the religion in Egypt during his reign. After the death of Akhenaten, his son, Tutankhamun, reinstated the cult of Amun and the ban on religions in competition with Atenism was lifted.[24] The point of this transition can be seen in the name change of Tutankhaten into Tutankhamun indicating the loss of favor in the worship of Aten.[9] The cult of Aten was still in Egypt for another ten years or so as it faded and there was no purge of the cult after Akhenaten's death. When Tutankhamun came into power, his religious reign was one of tolerance, the only difference was that Aten was no longer the only god.[1] Tutankhamun rebuilt the temples that were destroyed during Akhenaten's reign and he reinstated the old pantheon of gods. This return to the gods that were before Aten was "a move based publicly on the doctrine that Egypt's woes stemmed directly from its ignoring the gods, and in turn the gods' abandonment of Egypt".[1]

Names derived from Aten

- Akhenaten: "Effective spirit of the Aten".

- Akhetaten: "Horizon of the Aten", Akhenaten's capital. The archaeological site is known as Amarna.

- Ankhesenpaaten: "Her life is of the Aten".

- Beketaten: "Handmaid of the Aten".

- Meritaten: "She who is beloved of the Aten".

- Meketaten: "Behold the Aten" or "Protected by Aten".

- Neferneferuaten: "Beautiful are the beauties of Aten".

- Paatenemheb: "The Aten on jubilee".

- Tutankhaten: "Living image of the Aten". Original name of Tutankhamun.

- Silver Aten: The moon.

Gallery

Limestone fragment column showing reeds and an early Aten cartouche. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Limestone fragment column showing reeds and an early Aten cartouche. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London Headless bust of Akhenaten or Nefertiti. Part of a composite red quartzite statue. Intentional damage. Four pairs of early Aten cartouches. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

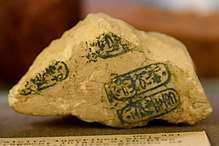

Headless bust of Akhenaten or Nefertiti. Part of a composite red quartzite statue. Intentional damage. Four pairs of early Aten cartouches. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London Inscribed limestone fragment showing early Aten cartouches, "the Living Ra Horakhty". Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

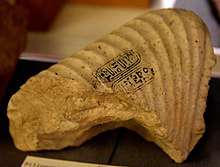

Inscribed limestone fragment showing early Aten cartouches, "the Living Ra Horakhty". Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London Fragment of a stela, showing parts of three late cartouches of Aten. There is a rare intermediate form of the god's name. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Fragment of a stela, showing parts of three late cartouches of Aten. There is a rare intermediate form of the god's name. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London Siliceous limestone fragment of a statue. There are late Aten cartouches on the draped right shoulder. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Siliceous limestone fragment of a statue. There are late Aten cartouches on the draped right shoulder. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

See also

- Amun

- Atenism

- The Egyptian

- Great Hymn to the Aten

- Inti

- Pharaoh of the Exodus

- List of solar deities

- The spatial symbolism of the Voortrekker Monument

References

- Redford, Donald (1984). Akhenaten: The Heretic King. Princeton University Press. pp. 170–172. ISBN 978-0-691-03567-3.

- Fleming, Fergus, and Alan Lothian (1997). The Way to Eternity: Egyptian Myth. Duncan Baird Publishers. p. 52

- Khamneipur, Abolghassem (2015). Zarathustra : myth, message, history (1st ed.). Victoria, BC, Canada. p. 81. ISBN 9781460268810. OCLC 945369209.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. pp. 236–240

- M. Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, Vol. 1, 1980, p. 223

- Akhenaten and the Religion of Light. Cornell University Press. 2001. p. 8. ISBN 978-0801487255. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- Perry, Glenn (2004). The History of Egypt. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1. ISBN 9780313322648. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

aten nile river in sky syria.

- Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Handbook of Egyptian Mythology. ABC-CLIO. p. 110. ISBN 9781576072424. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- Freed, Rita E.; D'Auria, Sue; Markowitz, Yvonne J. (1999). Pharaohs of the sun : Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts in association with Bulfinch Press/Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 978-0878464708. OCLC 42450325.

- Goldwasser, Orly (2010). "The Aten is the "Energy of Light": New Evidence from the Script". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 46: 163. JSTOR 41431576.

- Groenewegen-Frankfort, Henriette Antonia (1951). Arrest and Movement: An Essay on Space and Time in the Representational Art of the Ancient Near East. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0674046566.

- "Aton". Britannica. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- "Aten, god of Egypt". Siteseen Ltd. June 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- "History embalmed: Aten". 2014 Siteseen Ltd. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- Pasquali, Stéphane (2011). "A sun-shade temple of Princess Ankhesenpaaten in Memphis?". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 97: 219. JSTOR 23269901.

- Redford, Donald B., ed. (2002). The ancient gods speak : a guide to Egyptian religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195154016. OCLC 49698760.

- Shaw, Ian (1994). "Balustrades, Stairs and Altars in the Cult of the Aten at el-Amarna". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 80: 109–127. doi:10.2307/3821854. JSTOR 3821854.

- Bennett, John (1965). "Notes on the 'Aten'". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 51: 207–209. doi:10.2307/3855637. JSTOR 3855637.

- Gunn, Battiscombe (1923). "Notes on the Aten and His Names". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 9 (3/4): 168–176. doi:10.2307/3854036. JSTOR 3854036.

- Jan Assmann, Religion and Cultural Memory: Ten Studies, Stanford University Press 2005, p. 59

- M. Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, Vol. 2, 1980, p. 96

- Dominic Montserrat, Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt, Routledge 2000, ISBN 0-415-18549-1, pp. 36ff.

- Brewer, Douglas J.; Emily Teeter (22 February 2007). Egypt and the Egyptians (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-521-85150-3.

- Hornung, Erik (2001). Akhenaten and the religion of light. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801487255. OCLC 48417401.

External links

_(Mus%C3%A9e_du_Caire)_(2076972086).jpg)