Hyksos

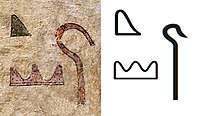

(𓋾𓈎𓈉 ḥḳꜣ-ḫꜣswt, Heqa-kasut for "Hyksos").

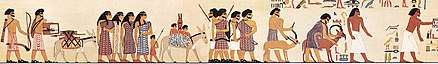

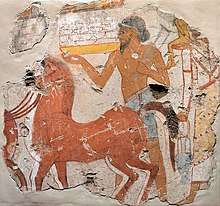

Tomb of Khnumhotep II (circa 1900 BC).[1][2]

This is the earliest known use of the term.[3]

| Periods and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All years are BC | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Early

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Ptolemaic (Hellenistic)

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

See also: List of Pharaohs by Period and Dynasty Periodization of Ancient Egypt | ||||||||||||||||||

The Hyksos (/ˈhɪksɒs/; Egyptian ḥqꜣ(w)-ḫꜣswt, Egyptological pronunciation: hekau khasut,[4] "ruler(s) of foreign lands"; Ancient Greek: Ὑκσώς, Ὑξώς) were foreigners of probable Levantine origin,[5][1] who established the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt (1650–1550 BC) based at the city of Avaris in the Nile delta, from where they ruled the northern part of the country. While the Hellenistic Egyptian historian Manetho portrayed the Hyksos as invaders and oppressors, modern Egyptology no longer believes that the Hyksos conquered Egypt in an invasion.[6] Instead, Hyksos rule had been preceded by groups of Canaanite peoples settled in the eastern delta who likely seceded from central Egyptian control near the end of the Thirteenth Dynasty.[7]

The Hyksos period marks the first in which Egypt was ruled by foreign rulers.[8] Many details of their rule, such as the true extent of their kingdom and even the names and order of their kings, remain uncertain. The Hyksos practiced many Levantine or Canaanite customs, and they also practiced many Egyptian customs.[9] They have been credited with introducing several technological innovations to Egypt, such as the horse and chariot, as well as the sickle sword and the composite bow, however this theory remains disputed.[10]

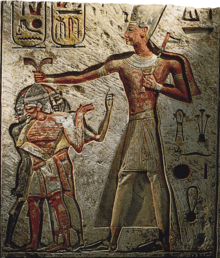

The Hyksos did not control all of Egypt, instead, they coexisted with the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Dynasties, which was based in Thebes.[11] They were eventually conquered by Ahmose I, who founded the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Ahmose's conquest was preceded by warfare between the Hyksos and Ahmose's predecessors Seqenenra Taa and Kamose of the Seventeenth Dynasty. The sources which describe the war are poor and written from the Theban perspective.[12] In the following centuries, the Egyptians would portray the Hyksos as blood-thirsty and oppressive foreign rulers.

Name

Etymology

| Hyksos in hieroglyphs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ḥḳꜣ-ḫꜣsw / ḥḳꜣw-ḫꜣswt,[13][14] "hekau khasut"[4][15] Ruler(s) of the foreign countries[13] | |||||||

| Greek | Hyksos (Ὑκσώς), Hykussos (Ὑκουσσώς)[16] | ||||||

| |||||||

The term "Hyksos" is derived, via the Greek Ὑκσώς (Hyksôs), from the Egyptian expression 𓋾𓈎𓈉 (ḥḳꜣ-ḫꜣswt or ḥḳꜣw-ḫꜣswt), meaning "rulers [of] foreign lands".[13][14] The Greek form is likely a textual corruption of an earlier Ὑκουσσώς (Hykoussôς).[16]

The first century CE Jewish historian Josephus gives the name as meaning "shepherd kings" or "captive kings" in his Against Apion, where he describes the Hyksos as they appeared in the Hellenistic Egyptian historian Manetho.[18] Josephus's rendition may arise from a later Egyptian pronunciation of ḥḳꜣ-ḫꜣswt as ḥḳꜣ-šꜣsw, which was then understood to mean "lord of shepherds."[19] It is unclear if this translation was found in Manetho; an Armenian translation of an epitome of Manetho given by the late antique historian Eusebius gives the correct translation of "foreign kings".[20]

Use

Properly speaking, the term Hyksos refers to foreign rulers, especially of the Fifteenth Dynasty, rather than a people, but it was already being used as an ethnic term by Josephus.[21] The Egyptian term "Hyksos " (ḥḳꜣ-ḫꜣswt) was also used to refer to various Nubian and and especially Asiatic rulers both before and after the fifteenth dynasty.[22][23][4] Its earliest recorded use is found circa 1900 BC in the tomb of Khnumhotep II of the Twelfth Dynasty to label a Bedouin or Canaanite ruler named "Abisha the Hyksos" (using the standard 𓋾𓈎𓈉, ḥḳꜣ-ḫꜣswt, "Heqa-kasut" for "Hyksos").[3][24]

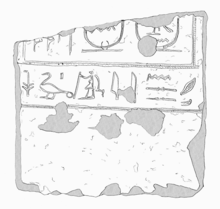

Based on the use of the name in a Hyksos inscription of Sakir-Har from Avaris, the name was used by the Hyksos as a title for themselves.[25] However, Kim Ryholt, argues that "Hyksos" was not an official title of the rulers of the Fifteenth dynasty, and is never encountered together with royal titulary, only appearing as the title in the case of Sakir-Har. According to Ryholt, "Hyksos" was rather a generic term which is encountered separately from royal titulary, and in regnal lists after the end of the Fifteenth Dynasty itself.[26] However, Vera Müller writes: "Considering that S-k-r-h-r is also mentioned with three names of the traditional Egyptian titulary (Horus name, Golden Falcon name and Two Ladies name) on the same monument, this argument is somehow strange."[27] David Candelora also argues that the Hyksos gave the title to themselves.[28]

Scarabs also attest the use of this title for pharaohs usually assigned to the Fourteenth or Sixteenth Dynasty of Egypt, who are sometimes called "'lesser' Hyksos."[27] All other texts in the Ancient Egyptian language except the Turin King List do not call the Hyksos by this name, instead referring to them as Asiatics (ꜥꜣmw).[29]

Origins

Ancient historians

In his epitome of Manetho, Josephus connected the Hyksos with the Jews,[31] but he also called them Arabs. In their own epitomes of Manetho, the Late antique historians Sextus Julius Africanus and Eusebius say that the Hyksos came from Phoenicia.[18] Until the excavation and discovery of Tell El-Dab'a (the site of the Hyksos capital Avaris) in 1966, historians relied on these accounts for the Hyksos period.[32][5]

Modern historians

Material finds at Tell El-Dab'a indicate that the Hyksos originated in either the northern or southern Levant.[5] The Hyksos' personal names indicate that they spoke a Western Semitic language and "may be called for convenience sake Canaanites."[33] Kamose, the last king of the Theban 17th Dynasty, refers to Apepi as a "Chieftain of Retjenu" in a stela that implies a Levantine background for this Hyksos king.[34] According to Anna-Latifa Mourad, the Egyptian application of the term ꜥꜣmw to the Hyksos could indicate a range of backgrounds, including newly arrived Levantines or people of mixd Levantine-Egyptian origin.[35]

Due to the work of Manfred Bietak, which found on similarities in architecture, ceramics, and burial practices, currently a northern Levantine origin of the Hyksos is favored.[36] Based particularly on temple architecture, Bietak argues for strong parallels between the religious practices of the Hyksos at Avaris with those of the area around Byblos, Ugarit, Alalakh, and Tell Brak, defining the "spiritual home" of the Hyksos as "in northernmost Syria and northern Mesopotamia".[37] The connection of the Hyksos to Retjenu also suggests a northern Levantine origin: "Theoretically, it is feasible to deduce that the early Hyksos, as the later Apophis, were of elite ancestry from Rṯnw, a toponym [...] cautiously linked with the Northern Levant and the northern region of the Southern Levant."[35]

Earlier arguments that the Hyksos names might be Hurrian have been rejected,[38] while early-twentieth-century proposals that the Hyksos were Indo-Europeans "fitted European dreams of Indo-European supremacy, now discredited."[39]

History

Background and arrival in Egypt

The only ancient account of the whole Hyksos period is by the Hellenistic Egyptian historian Manetho, who, whoever, exists only as quoted by others.[44] As recorded by Josephus, Manetho describes the beginning of Hyksos rule thusly:

A people of ignoble origin from the east, whose coming was unforeseen, had the audacity to invade the country, which they mastered by main force without difficulty or even battle. Having overpowered the chiefs, they then savagely burnt the cities, razed the temples of the gods to the ground, and treated the whole native population with the utmost cruelty, massacring some, and carrying off the wives and children of others into slavery. (Contra Apion I.75-77)[45]

Manetho's invasion narrative is "nowadays rejected by most scholars."[6] Instead, it appears that the establishment of Hyksos rule was mostly peaceful and did not involve an invasion of an entirely foreign population.[46] Archaeology shows a continuous Asiatic presence at Avaris for over 150 years before the beginning of Hyksos rule,[47] with gradual Canaanite settlement beginning there c. 1800 BC during the Twelfth Dynasty.[14] Manfred Bietak argues that Hyksos "should be understood within a repetitive pattern of the attraction of Egypt for western Asiatic population groups that came in search of a living in the country, especially the Delta, since prehistoric times."[48]

The final powerful pharaoh of the Egyptian Thirteenth dynasty was Sobekhotep IV, who died around 1725 BC, after which Egypt appears to have splintered into various kingdoms, including one based at Avaris ruled by the Fourteenth dynasty.[7] Based on their names, this dynasty was already primarily of West Asian origin.[49] After an event in which their palace was burned,[49] the fourteenth dynasty would be replaced by the Hyksos Fifteenth Dynasty and would establish "loose control over northern Egypt by intimidation or force,"[50] thus greatly expanding the area under Avaris's control.[51] Kim Ryholt argues that the Fifteenth Dynasty invaded and displaced the Fourteenth, however Alexander Ilin-Tomich argues that this is "not sufficiently substantiated."[38]

Rule

The length of time the Hyksos ruled is unclear. The fragmentary Turin King List says that there were six Hyksos kings who collectively ruled 108 years,[52] however in 2018 Kim Ryholt proposed a new reading of as many as 149 years, while Thomas Schneider proposed a length between 160-180 years.[53]

The area under directed control of the Hyksos was probably limited to the eastern Nile delta.[11] The Hyksos claimed to be rulers of both Lower and Upper Egypt; however, their southern border was marked at Hermopolis and Cusae.[9] Some objects might suggest a Hyksos presence in Upper Egypt, however they may have been Theban war booty or attest simply to short term raids, trade, or diplomatic contact.[54] Although the royal seat was in Avaris, Memphis was probably also an important administrative center.[55] However, the nature of Hyksos control over the region of Thebes and Memphis remains unclear.[11] Most likely Hyksos rule covered the area from Middle Egypt to southern Palestine.[56] Older scholarship believed, due to the distribution of Hyksos goods with the names of Hyksos rulers in places such as Baghdad and Knossos, that Hyksos had ruled a vast empire, however it seems more likely to have been the result of diplomatic gift exchange and far-flung trade networks.[57][11]

The rule of the Hyksos overlaps with that of the native Egyptian pharaohs of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Dynasties, better known as the Second Intermediate Period. The Theban rulers of the Seventeenth Dynasty are known to have imitated the Hyksos both in their architecture and regnal names.[58] There is evidence of friendly relations between the Hyksos and Thebes, including possibly a marriage alliance, prior to the reign of the Theban pharaoh Seqenenra Taa.[59] Historically, scholars assumed that the other dynasties were "vassal" dynasties, an idea partially derived from the nineteenth-dynasty literary text The Quarrel of Apophis and Seqenenre,[60] in which it is said "the entire land paid tribute to him [Apepi], delivering their taxes in full as well as bringing all good produce of Egypt."[61] The belief in Hyksos vassalage was challenged by Ryholt as "a baseless assumption."[62] Roxana Flamini suggests instead that Hyksos exerted influence through (sometimes imposed) personal relationships and gift-giving.[63]

Wars with the Seventeenth Dynasty

The conflict between Thebes and the Hyksos is known exclusively from pro-Theban sources, and it is difficult to construct a chronology.[12] These sources propagandistically portray the conflict as a war of national liberation. This perspective was formerly taken by scholars as well but is no longer thought to be accurate.[64][65]

Hostilities between the Hyksos and the Theban Seventeenth Dynasty appear to have begun during the reign of Theban king Seqenenra Taa. Seqenenra Taa's mummy shows that he was killed by several blows of an axe to the head, apparently in battle with the Hyksos.[66] It is unclear why hostilities may have started, but the much later fragmentary New Kingdom tale The Quarrel of Apophis and Seqenenre blames the Hyksos ruler Apepi/Apophis for initiating the conflict by demanding that Seqenenra Taa remove a pool of hippopotamuses near Thebes.[59] However, this is a satire on the Egyptian story-telling genre of the "king's novel" rather than a historical text.[66]

Three years later, Seqenenra Taa's successor Kamose initiated a campaign against several cities loyal to the Hyksos, the account of which he had preserved on the Carnarvon Tablet.[67] The text includes a complaint by Kamose about the divided and occupied state of Egypt:

To what effect do I perceive it, my might, while a ruler is in Avaris and another in Kush, I sitting joined with an Asiatic and a Nubian, each man having his (own) portion of this Egypt, sharing the land with me. There is no passing him as far as Memphis, the water of Egypt. He has possession of Hermopolis, and no man can rest, being deprived by the levies of the Setiu. I shall engage in battle with him and I shall slit his body, for my intention is to save Egypt, striking the Asiatics.[68]

Following a common literary device, Kamose's advisors are portrayed as trying to dissuade the king, but the king attacks anyway.[67] He recounts his destruction of the city of Nefrusy as well as several other cities loyal to the Hyksos.[66] On a second stele, Kamose claims to have captured Avaris, but returned to Thebes after capturing a messenger between Apepi and the king of Kush.[66]

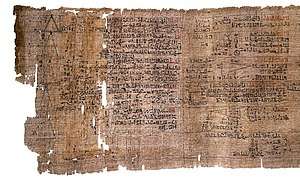

Ahmose I continued the war against the Hyksos, most likely conquering Memphis, Tjaru and Heliopolis early in his reign, the latter two of which are mentioned in an entry of the Rhind mathematical papyrus.[66] Knowledge of Ahmose I's campaigns against the Hyksos mostly comes from the tomb of Ahmose, son of Ebana, who gives a first person account claiming that Ahmose I sacked Avaris:[70]

Then there was fighting Egypt to the south of this town [Avaris], and I carried off a man as a living captive. I went down into the water—for he was captured on the city side—and crossed the water carrying him. [...] Then Avaris was despoiled, and I brought spoil from there.[71]

Thomas Schneider places the conquest in year 18 of Ahmose's reign.[72] However, excavations of Tell El-Dab'a (Avaris) show no widespread destruction of the city, which instead seems to have been abandoned by the Hyksos.[66] Manetho, as recorded in Josephus, states that the Hyksos were allowed to leave after concluding a treaty:[73]

Thoumosis [...] invested the walls [of Avaris] with an army of 480,000 men, and endeavoured to reduce [the Hyksos] to submission by siege. Despairing of achieving his object, he concluded a treaty, under which [the Hyksos] were all to evacuate Egypt and go whither they would unmolested. Upon these terms no fewer than two hundred and forty thousand, entire households with their possessions, left Egypt and traversed the desert to Syria. (Contra Apion I.88-89)[74]

Although Manetho indicates that the Hyksos population was expelled to the Levant, there is no archaeological evidence for this, and Manfred Bietak argues on the basis of archaeological finds throughout Egypt that it is likely that numerous Asiatics were resettled in other locations in Egypt as artisans and craftsmen.[75]

Rulers

The names, the order, length of rule, and even the total number of the Fifteenth Dynasty rulers are not known with full certainty. After the end of their rule, the Hyksos kings were not considered to have been legitimate rulers of Egypt and were therefore omitted from most king lists.[76] The fragmentary Turin King List included six Hyksos kings, however only the name of the last, Khamudi, is preserved.[77] Ryholt associates three other rulers known from inscriptions with the dynasty, Khyan, Sakir-Har, and Apepi.[78] The name of Khyan's son, Yanassi, is also preserved from Tell El-Dab'a.[51] The two best attested kings are Khyan and Apepi,[79]

Some kings are attested from either fragments of the Turin King List or from other sources who may have been Hyksos rulers. According to Ryholt, kings Semqen and Aperanat, known from the Turin King List, may have been early Hyksos rulers,[80] however Jürgen von Beckerath assigns these kings to the Sixteenth Dynasty of Egypt.[81] Another king known from scarabs, Sheshi,[82] is believed by "many [...] scholars" to be a Hyksos king,[83] however Ryholt assigns this king to the Fourteenth Dynasty of Egypt.[84]

Josephus's epitome of Manetho lists the rulers of the fifteenth dynasty as Salatis, Bnon, Apachnas, Apophis, Jannas, and Assis.[89] It is difficult to reconcile the Turin King List and other sources with names known from Manetho via Josephus.[82] The name Apepi/Apophis appears on both lists, however.[90] Bietak identifies Sakir-Har with Salitis,[91] while Assis may be Yanassi,[51] although it is also possible that he is Jannas.[92] Thomas Schneider instead proposes that Khyan is identical with Apachnas and Sakir-Har with Assis.[93] Schneider's proposed identifications, with reconstructed Semitic names for the pharaohs, are found in the table below:

| Name in Manetho | Name in other sources | Reconstructed Semitic name |

|---|---|---|

| Salitis | ? | Šarā-Dagan (Šȝrk[n]) |

| Bnon | ? | *Bin-ʿAnu |

| Apachnan | Khyan | (ʿApaq-)Hajran |

| Iannas | Yanassi | Jinaśśi’-Ad |

| Archles/Assis | Sakir-Har | Sikru-Haddu |

| Apophis | Apepi | Apapi |

| - | Khamudi | Halmu’di |

None of the proposed identifications besides of Apepi and Apophis is considered certain.[95]

It is seen as secure that Apepi and Khamudi are the last two kings of the dynasty,[97] and Apepi is attested as a contemporary of seventeenth-dynasty pharaohs Kamose and Ahmose I.[98] The only other kings for whom their order is certain are Khyan and his son Yanassi.[99] Ryholt, however, has proposed that Yanassi may not have ruled in his own right.[100] Ryholt proposes a dynastic order of for the final three pharaohs of the fifteenth dynasty as: Khyan (10 years), Apophis (40 years), and then Khamudi (less than ten years).[101] However, on the basis of the Rhind mathematical papyrus, Schneider argues that Khamudi must have reigned at least 11 years,[72] and David Aston finds Ryholt's suggestion that Khyan immediately preceded Apepi unlikely.[93] Schneider agrees that Sakir-Har may be the first of the dynasty, although he does not identify him with Salitis.[94]

In Sextus Julius Africanus's epitome of Manetho, the rulers of Sixteenth Dynasty are also identified as "shepherds" (i.e. Hyksos) rulers.[102] Following the work of Ryholt in 1997, most but not all scholars now identify the sixteenth dynasty as a native Egyptian dynasty based in Thebes, following Eusebius's epitome of Manetho; this dynasty would be contemporary to the Hyksos.[103]

Society and culture

Royal construction and patronage

The Hyksos do not appear to have produced any court art,[104] instead appropriating monuments from earlier dynasties by writing their names on them. Many of these are inscribed with the name of King Khyan.[105] A large palace at Avaris has been uncovered, built in the Levantine rather than the Egyptian style, most likely by Khyan.[106] King Apepi is known to have patronized Egyptian scribal culture, commissioning the copying of the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus.[107]

Religion and culture

The Hyksos show a mix of Egyptian and Levantine cultural traits.[9] Temples in Avaris existed both in Egyptian and Levantine style, the later presumably for Levantine gods.[108] The Hyksos are known to have worshiped the Canaanite storm god Baal-zephon, who was associated with the Egyptian god Set.[109] Set appears to have been the patron god of Avaris as early as the Fourteenth dynasty.[110] Hyksos iconography of their kings on some scarabs shows a mixture of Egyptian pharaonic dress with a raised club, the iconography of Baal-zephon.[8] Despite later sources claiming the Hyksos were opposed to the worship of other gods, votive objects given by Hyksos rulers to gods such as Ra, Hathor, Sobek, and Wadjet have also survived.[111]

Burial practices

There are also no surviving Hyksos funeral monuments at Memphis in the Egyptian style, though these may have been destroyed.[112] Evidence for distinct Hyksos burial practices in the archaeological record include burying their dead within settlements rather than outside them like the Egyptians.[113] While some of the tombs include Egyptian-style chapels, they also include burials of young females, probably sacrifices, placed in front of the tomb chamber.[106] The Hyksos also practiced the burial of horses and other equids, likely a composite custom of the Egyptian association of the god Seth with the donkey and near-eastern notions of equids as representing status.[114]

Technology

The Hyksos use of horse burials suggest that the Hyksos introduced both the horse and the chariot to Egypt,[115] however no archaeological, pictorial, or textual evidence exists that the Hyksos possessed chariots, which are first mentioned as ridden by the Egyptians in warfare against them by Ahmose, son of Ebana at the close of Hyksos rule.[116] Josef Wegner further argues that horse-riding may have been present in Egypt as early as the late Middle Kingdom, prior to the adoption of chariot technology.[117] Traditionally, the Hyksos have also been credited with introducing a number of other military innovations, such as the sickle-sword and composite bow; however, "[t]o what extent the kingdom of Avaris should be credited for these innovations is debatable," with scholarly opinion currently divided.[10] It is also possible that the Hyksos introduced more advanced bronze working and weaving techniques, though this is inconclusive.[118] They may have worn full-body armor, and introduced new musical instruments to Egypt as well.[118]

Trade and economy

The early period of Hyksos period established their capital of Avaris "as the commercial capital of the Delta".[119] The trading relations of the Hyksos were mainly with Canaan and Cyprus.[120][9] Trade with Canaan is said to have been "intensive", especially with many imports of Canaanite wares, and may have reflected the Canaanite origins of the dynasty.[121] Trade was mostly with the cities of the northern Levant, but connections with the southern Levant also developed.[35] Additionally, trade was conducted with Faiyum, Memphis), oases in Egypt, Nubia, and Mesopotamia.[119] Trade relations with Cyprus were also very important, particularly at the end of the Hyksos period.[122][9] Aaron Burke has interpreted the equid burials in Avaris of evidence that the people buried with them were involved in the caravan trade.[123] Anna-Latifa Mourad argues that "Hyksos were particularly interested in opening new avenues of trade, securing strategic posts in the eastern Delta that could give access to land-based and sea-based trade routes."[119] These include the apparent Hyksos settlements of Tell el-Habwa I and Tell el-Maskhuta in the eastern Delta.[124]

According to the Kamose stelae, the Hyksos imported "chariots and horses, ships, timber, gold, lapis lazuli, silver, turquoise, bronze, axes without number, oil, incense, fat and honey".[9] The Hyksos also exported large quantities of material looted from southern Egypt, especially Egyptian sculptures, to the areas of Canaan and Syria.[121] These transfers of Egyptian artifacts to the Near East may especially be attributed to king Apepi.[121] The Hyksos also produced local, Levantine-influenced industries, such as Tell el-Yahudiyeh Ware.[119]

Biblical connections

According to researches on the historicity of the Old Testament, the descent of Abraham into Egypt as recorded in Genesis 12:10-20 should correspond to the early years of the 2nd milenium BCE, which is before the time the Hyksos ruled in Egypt, but would coincide with the Semitic parties known to have visited the Egyptians circa 1900 BCE, as documented in the painting of a West-Asiatic procession of the tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hasan.[125] It might be possible to associate Abraham to such known Semitic visitors to Egypt, as they would have been ethnically connected.[125][126] The period of Joseph and Israel in Egypt (Genesis 39:50), where they were in favour at the Egyptian court and Joseph held high administrative positions next to the ruler of the land, would correspond to the time the Hyksos ruled in Egypt, during the Fifteenth Dynasty.[125] The time of Moses and the expulsion to Palestine related in the The Exodus could also correspond to the explusion of the Hyksos from Egypt.[125][126]

Legacy

The Hyksos' rule continued to be condemned by New Kingdom pharaohs such as Hatshepsut, who, 80 years after their defeat, claimed to rebuild many shrines and temples they had neglected.[104] The nineteenth-dynasty story The Quarrel of Apophis and Seqenenre claimed that the Hyksos worshiped no god but Set, making the conflict into one between Ra, the patron of Thebes, and Set as patron of Avaris.[128] Furthermore, the battle with the Hyksos was interpreted in light of the mythical battle between the gods Horus and Set, transforming Set into an Asiatic deity while also allowing for the integration of Asiatics into Egyptian society.[129]

Manetho's portrayal of the Hyksos, written nearly 1300 years after the end of Hyksos rule and found in Josephus, is even more negative than the New Kingdom sources.[104] This account portrayed the Hyksos "as violent conquerors and oppressors of Egypt" has been highly influential for perceptions of the Hyksos until modern times.[130] Marc van de Mieroop argues that Josephus's portrayal of the initial Hyksos invasion is no more trustworthy than his later claims that they were related to the Exodus, supposedly portrayed in Manetho as performed by a band of lepers.[131] The Hyksos supposed connections to the Exodus have continued to inspire interest in them.[39]

See also

- Israelites

- Mitanni

- Kassites

- Sea peoples

- Hittites

- Philistines

- Maryannu

- Sino-Babylonianism

Notes

- van de Mieroop 2011, p. 131.

- Bard 2015, p. 188.

- Willems 2010, p. 96.

- Bourriau 2000, p. 174.

- Mourad 2015, p. 10.

- Ilin-Tomich 2016, p. 5.

- Bourriau 2000, pp. 177-178.

- Morenz & Popko 2010, p. 104.

- Bourriau 2000, p. 182.

- Ilin-Tomich 2016, p. 12.

- Ilin-Tomich 2016, p. 7.

- Morenz & Popko 2010, pp. 108-109.

- Flammini 2015, p. 240.

- Ben-Tor 2007, p. 1.

- Spelling of the hieroglyphs in sources describing the archaeological record of the historical Hyksos: first set of characters is the singular, as appearing in Abisha the Hyksos in the tomb of Khnumhotep II, c.1900 BC. See Kamrin, Janice (2009). "The Aamu of Shu in the Tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hassan" (PDF). Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. Vol. 1:3.. The second set is in the plural, as appears in the inscriptions of known Hyksos rulers Sakir-Har and Aperanat, see Gertoux, Gerard. "Dating the war of the Hyksos": page 17. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: extra text (link), and also "The Sakir-Har doorjamb inscription (slide 12)" (PDF). - Schneider 2008, p. 305.

- Kamrin, Janice (2009). "The Aamu of Shu in the Tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hassan" (PDF). Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. Vol. 1:3.

- Mourad 2015, p. 9.

- Morenz & Popko 2010, pp. 103-104.

- Verbrugghe & Wickersham 1996, p. 99.

- Bietak 2010, p. 139.

- Candelora 2017, pp. 208=209.

- Ryholt 1997, pp. 123-124.

- Curry, Andrew (2018). "The Rulers of Foreign Lands - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org.

- Candelora 2017, p. 204.

- Ryholt 1997, p. 123-125.

- Müller 2018, p. 211.

- Candelora 2017, p. 216.

- Candelora 2017, pp. 206-208.

- "Tomb-painting British Museum". The British Museum.

- Assmann.

- Flammini 2015, p. 236.

- Bietak 2016, pp. 267-268.

- Ryholt 1997, p. 128.

- Mourad 2015, p. 216.

- Mourad 2015, p. 11.

- Bietak 2019, p. 61.

- Ilin-Tomich 2016, p. 6.

- Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 166.

- Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 131.

- Kamrin, Janice (2009). "The Aamu of Shu in the Tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hassan" (PDF). Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. Vol. 1:3.

- Curry, Andrew (2018). "The Rulers of Foreign Lands - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org.

- "Tomb-painting British Museum". The British Museum.

- Raspe 1998, p. 126-128.

- Josephus 1926, p. 196.

- Mourad 2015, p. 130.

- Bietak 2006, p. 285.

- Biatek 2006, p. 285.

- Bietak 2019, p. 47.

- Bietak 1999, p. 377.

- Bourriau 2000, p. 180.

- Ryholt 1997, p. 186.

- Aston 2018, pp. 31-32.

- Popko 2013, p. 3.

- Bourriau 2000, p. 183.

- Popko 2013, p. 2.

- Morenz & Popko 2010, p. 105.

- Morenz & Popko 2010, p. 108.

- Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 160.

- Flamini 2015, pp. 236-237.

- Simpson 2003, p. 70.

- Ryholt 1997, p. 323.

- Flamini 2015, pp. 239-243.

- Morenz & Popko 2010, p. 109.

- Popko 2013, pp. 1-2.

- Popko 2013, p. 4.

- Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 161.

- Simpson 2003, p. 346.

- O'Connor 2009, pp. 116-117.

- Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 177.

- Lichthelm 2019, p. 321.

- Schneider 2006, p. 195.

- Bourriau 2003, pp. 201-202.

- Josephus 1926, pp. 197-199.

- Bietak 2010, pp. 170-171.

- Ben-Tor 2007, p. 2.

- Ryholt 1997, p. 118.

- Ryholt 1997, pp. 119-120.

- Aston 2018, p. 18.

- Ryholt 1997, pp. 121-122.

- von Beckerath 1999, pp. 120-121.

- Bietak 1999, p. 378.

- Müller 2018, p. 210.

- Ryholt 1997, p. 409.

- Candelora, Danielle. "The Hyksos". www.arce.org. American Research Center in Egypt.

- Roy, Jane (2011). The Politics of Trade: Egypt and Lower Nubia in the 4th Millennium BC. BRILL. pp. 291–292. ISBN 978-90-04-19610-0.

- "A head from a statue of an official dating to the 12th or 13th Dynasty (1802–1640 B.C.) sports the mushroom-shaped hairstyle commonly worn by non-Egyptian immigrants from western Asia such as the Hyksos." in "The Rulers of Foreign Lands - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org.

- Potts, Daniel T. (2012). A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. John Wiley & Sons. p. 841. ISBN 978-1-4443-6077-6.

- Josephus 1926, pp. 192-195.

- Ilin-Tomich 2016, pp. 7-8.

- Bourriau 2000, p. 179.

- Ryholt 1997, pp. 120-121.

- Aston 2018, p. 17.

- Schneider 2006, p. 194.

- Ilin-Tomich 2016, p. 11.

- O'Connor 2009, pp. 115-116.

- Ilin-Tomich 2016, pp. 6-7.

- Aston 2018, p. 16.

- Aston 2018, pp. 15-16.

- Ryholt 1997, p. 256.

- Ryholt 1997, pp. 119, 188.

- Bourriau 2003, p. 179.

- Ilin-Tomich 2016, p. 3.

- Bietak 1999, p. 379.

- Müller 2018, p. 212.

- Bard 2015, p. 213.

- van de Mieroop 2011, pp. 151-153.

- O'Connor 2009, p. 109.

- Bietak 1999, pp. 377-378.

- Bourriau 2000, p. 177.

- Ryholt 1997, pp. 148-149.

- Bouriau 2000, p. 183.

- Bietak 2016, p. 268.

- Mourad 2015, p. 15.

- Hernandez 2014, p. 112.

- Herslund 2018, p. 151.

- Wegner 2015, p. 76.

- Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 149.

- Mourad 2015, p. 129.

- Ryholt 1997, pp. 138-139, 142.

- Ryholt 1997, pp. 138-139.

- Ryholt 1997, p. 141.

- Burke 2019, p. 80.

- Mourad 2015, pp. 129-130.

- Douglas, J. D.; Tenney, Merrill C. (2011). Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary. Zondervan Academic. p. 1116. ISBN 978-0-310-49235-1.

- Isbouts, Jean-Pierre (2007). The Biblical World: An Illustrated Atlas. National Geographic Books. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-4262-0138-7.

- Richardson, Dan (2013). Cairo and the Pyramids (Rough Guides Snapshot Egypt). Rough Guides UK. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4093-3544-3.

- Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 163.

- Assmann 2003, pp. 199-200.

- Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 164.

- Van de Mieroop 2011, pp. 164-165.

References

- Aston, David A. (2018). "How Early (and How Late) Can Khyan Really Be: An Essay Based on ›Conventional Archaeological Methods‹". In Forstner-Müller, Irene; Moeller, Nadine (eds.). THE HYKSOS RULER KHYAN AND THE EARLY SECOND INTERMEDIATE PERIOD IN EGYPT: PROBLEMS AND PRIORITIES OF CURRENT RESEARCH. Proceedings of the Workshop of the Austrian Archaeological Institute and the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Vienna, July 4 – 5, 2014. Holzhausen. pp. 15–56. ISBN 978-3-902976-83-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Assmann, Jan (2003). The mind of Egypt: history and meaning in the time of the Pharaohs. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674012110.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bard, Kathryn A. (2015). An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt (2 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9780470673362.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. von Zabern. ISBN 3-8053-2591-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ben-Tor, Daphne (2007). Scarabs, Chronology, and Connections: Egypt and Palestine in the Second Intermediate Period (PDF). Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bietak, Manfred (2019). "The Spiritual Roots of the Hyksos Elite: An Analysis of Their Sacred Architecture, Part I". In Bietak, Manfred; Prell, Silvia (eds.). The Enigma of the Hyksos. Harrassowitz. pp. 47–67. ISBN 9783447113328.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bietak, Manfred (2016). "The Egyptian community in Avaris during the Hyksos period". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. 26: 263–274. JSTOR 44243953.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bietak, Manfred (2010). "FROM WHERE CAME THE HYKSOS AND WHERE DID THEY GO?". In Maréee, Marcel (ed.). THE SECOND INTERMEDIATE PERIOD (THIRTEENTH–SEVENTEENTH DYNASTIES): Current Research, Future Prospects. Peeters. pp. 139–181.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bietak, Manfred (2006). "The predecessors of the Hyksos". In Gitin, Seymour; Wright, Edward J.; Dessel, J. P. (eds.). Confronting the Past: Archaeological and Historical Essays on Ancient Israel in Honor of William G. Dever. Eisenbrauns.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bietak, Manfred (1999). "Hyksos". In Bard, Kathryn A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. pp. 377–379.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bourriau, Janine (2000). "The Second Intermediate Period (c. 1650-1550 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burke, Aaron A. (2019). "Amorites in the Eastern Nile Delta: The Identity of Asiatics at Avaris during the Early Middle Kingdom". In Bietak, Manfred; Prell, Silvia (eds.). The Enigma of the Hyksos. Harrassowitz. pp. 67–91. ISBN 9783447113328.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Candelora, Danielle (2017). "Defining the Hyksos: A Reevaluation of the Title ḥḳꜣ-ḫꜣswt and Its Implications for Hyksos Identity". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 53: 203–221. doi:10.5913/jarce.53.2017.a010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Flammini, Roxana (2015). "BUILDING THE HYKSOS' VASSALS: SOME THOUGHTS ON THE DEFINITION OF THE HYKSOS SUBORDINATION PRACTICES". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. 25: 233–245. JSTOR 43795213.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ilin-Tomich, Alexander (2016). "Second Intermediate Period". In Wendrich, Willeke; et al. (eds.). UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Josephus, Flavius (1926). Josephus in Eight Volumes, 1: The Life; Against Apion. Translated by Thackeray, H. St. J.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hernández, Roberto A. Díaz (2014). "The Role of the War Chariot in the Formation of the Egyptian Empire in the Early 18th Dynasty". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 43: 109–122. JSTOR 44160271.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Herslund, Ole (2018). "Chronicling Chariots: Texts, Writing and Language of New Kingdom Egypt". In Veldmeijer, André J; Ikram, Salima (eds.). Chariots in Ancient Egypt : The Tano Chariot, A Case Study. Sidestone Press. ISBN 9789088904684.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lichthelm, Miriam, ed. (2019). Ancient Egyptian Literature. University of California Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvqc6j1s. JSTOR j.ctvqc6j1s.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morenz, Ludwig D.; Popko, Lutz (2010). "The Second Intermediate Period and the New Kingdom". In Lloyd, Alan B. (ed.). A Companion to Ancient Egypt. 1. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 101–119.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mourad, Anna-Latifa (2015). Rise of the Hyksos: Egypt and the Levant from the Middle Kingdom to the early Second Intermediate Period. Oxford Archaeopress. doi:10.2307/j.ctvr43jbk. JSTOR j.ctvr43jbk.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Müller, Vera (2018). "Chronological Concepts for the Second Intermediate Period and Their Implications for the Evaluation of Its Material Culture". In Forstner-Müller, Irene; Moeller, Nadine (eds.). THE HYKSOS RULER KHYAN AND THE EARLY SECOND INTERMEDIATE PERIOD IN EGYPT: PROBLEMS AND PRIORITIES OF CURRENT RESEARCH. Proceedings of the Workshop of the Austrian Archaeological Institute and the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Vienna, July 4 – 5, 2014. Holzhausen. pp. 199–216. ISBN 978-3-902976-83-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Connor, David (2009). "Egypt, the Levant, and the Aegean: From the Hyksos Period to the Rise of the New Kingdom". In Aruz, Joan; Benzel, Kim; Evans, Jean M. (eds.). Beyond Babylon : art, trade, and diplomacy in the second millennium B.C. Yale University Press. pp. 108–122. ISBN 9780300141436.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Popko, Lutz (2013). "Late Second Intermediate Period". In Wendrich, Willeke; et al. (eds.). UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Raspe, Lucia (1998). "Manetho on the Exodus: A Reappraisal". Jewish Studies Quarterly. 5 (2): 124–155. JSTOR 40753208.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ryholt, Kim (1997). The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period c.1800-1550 B.C. Museum Tuscalanum Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schneider, Thomas (2006). "The Relative Chronology of the Middle Kingdom and the Hyksos Period". In Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David A. (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Brill. pp. 168–196. ISBN 9004113851.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schneider, Thomas (2008). "DAS ENDE DER KURZEN CHRONOLOGIE: EINE KRITISCHE BILANZ DER DEBATTE ZUR ABSOLUTEN DATIERUNG DES MITTLEREN REICHES UND DER ZWEITEN ZWISCHENZEIT". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. 18: 275–313. JSTOR 23788616.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simpson, William Kelly; et al., eds. (2003). The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, and Poetry. Yale University Press. JSTOR j.ctt5vm2m5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van de Mieroop, Marc (2011). A History of Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405160704.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verbrugghe, Gerald P.; Wickersham, John M. (1996). Berossos and Manetho, introduced and translated: native traditions in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472107224.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wegner, Josef (2015). "A ROYAL NECROPOLIS AT SOUTH ABYDOS: New Light on Egypt's Second Intermediate Period". Near Eastern Archaeology. 78 (2): 68–78. JSTOR 10.5615/neareastarch.78.2.0068.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Willems, Harco (2010). "The First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom". In Lloyd, Alan B. (ed.). A Companion to Ancient Egypt. 1. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 81–100.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hyksos. |

.jpg)

.jpg)