Pepi I Meryre

Pepi I Meryre (also Pepy I) was the third king of the Sixth dynasty of Egypt, ruling for over 40 years during the second half of the 24th Century BC, toward the end of the Old Kingdom period. Pepi I was the son of his second predecessor Teti, ascending the throne only after the brief and enigmatic reign of the shadowy Userkare. Pepi's mother was queen Iput, who may have been a daughter of Unas, final ruler of the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt.

| Pepi I Meryre | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pepy, Phios, Phius, φιός | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lifesize copper statue of Pepi I, Cairo Museum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | Duration: likely around five decades, in the second half of the 24th century BC or early 23rd century BC[note 1] (6th Dynasty) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coregency | with his son Merenre at the end of his reign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Userkare | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Merenre Nemtyemsaf I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Ankhesenpepi I, Ankhesenpepi II, Nubwenet, Meritites IV, Inenek-Inti, Mehaa, Nedjeftet and at least one more unidentified queen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Merenre Nemtyemsaf I ♂, Pepi II ♂, Hornetjerkhet ♂, Tetiankh ♂, Neith ♀, Iput ♀ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Teti | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Iput | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Pyramid of Pepi I in South Saqqara | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Pyramid Pepi Men-nefer, numerous Ka-chapels | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pepi seems to have faced the decline of the pharaoh's power, which he tried to buttress by forming alliances with the provincial nomarch of Abydos, two daughters of whom became queens of Egypt. Pepi's first throne name was Neferdjahor which the king later altered to Meryre meaning "beloved of Rê".[14]

Pepi was succeeded by his son Merenre Nemtyemsaf I, who reigned only briefly. He was in turn succeeded by Pepi II, who may have been another son of Pepi I by Ankhesenpepi II, although he could instead be a grandson of Pepi I by Merenre I. Pepi II was the last great pharaoh of the Old Kingdom period.

Family

Parents

Pepi was the son of Teti and queen Iput,[15] The latter is directly attested by a relief on a decree uncovered in Koptos, which mentions Iput as Pepi's mother, as well as by inscriptions in her pyramid to the same effect.[16] In addition, she bore the title of "king's mother" and her tomb, originally a mastaba, was transformed into a pyramid during Pepi's reign. She seems to have died before Pepi's accession to the throne.[17] Iput may have been a daughter of Unas the last pharaoh of the Fifth Dynasty,[2] although this remains uncertain and debated.[18]

Consorts

At least eight consorts of Pepi I have been identified. Queens Meritites IV,[19] Nubwenet[20] and Inenek-Inti[21] have been proposed as they are buried in pyramids adjacent to that of Pepi.[22] The case of Meritites remains debated however as she could also be an Eighth Dynasty queen, buried here to indicate her filiation to Pepi I.[19] Three more queens were Mehaa, who is named in the tomb of her son Hornetjerkhet, Nedjeftet who is mentioned on relief fragments,[23] and a queen, buried in Pepi I's pyramid complex, whose name is lost.[24]

Pepi's best attested wives were Ankhesenpepi I and Ankhesenpepi II.[note 2][25] Both were daughters of the nomarch of Abydos Khui and his wife Nebet.[25][23]

A final unnamed queen, only referred to by her title "Weret-Yamtes",[26] is known from the inscriptions uncovered in the tomb of Weni, an official serving Pepi. This queen apparently conspired against Pepi but was prosecuted when the conspiracy was discovered.[27]

Children

Pepi fathered at least three sons and a daughter. Ankhesenpepi I in all likelihood bore him the future pharaoh Merenre Nemtyemsaf I. In an alternative hypothesis, Hans Goedicke has proposed that Merenre's mother was the queen Were-Yamtes, responsible for the harem conspiracy against Pepi I. In this hypothesis, Ankhesenpepi I was claimed to be Merenre's mother to safeguard Merenre's claim to the throne.[28] Ankhesenpepi II was the mother of Pepi II Neferkare,[16] who was likely born at the very end of his father's reign given that he was only 6 upon ascending the throne after Merenre's own reign.[28] Another son of Pepi with an as yet unidentified consort was Teti-ankh, meaning "Teti lives".[16] Teti-ankh is known only from an ink inscription bearing his name discovered in Pepi's pyramid.[29] Buried nearby is prince Hornetjerkhet, a son of Pepi with queen Mehaa.[16]

At least two daughters of Pepi I have been tentatively identified: Neith[30] and Iput II,[31] both future wives of Pepi II.[32] For the latter, this remains uncertain as Iput II's title of "Daughter of the king" may only be honorary.[32] Neith may have been the mother of Pepi II's successor Merenre Nemtyemsaf II.[30]

Chronology

Relative chronology

The relative chronology of Pepi I's reign is well established by historical records, contemporary artifacts and archeological evidences, which agree that he succeeded Userkare and was in turn succeeded by Merenre I Nemtyemsaf.[34] For example, the near-contemporary South Saqqara Stone, a royal annal inscribed during the reign of Pepi II, gives the succession "Teti → Userkare → Pepi I → Merenre I", making Pepi the third king of the Sixth Dynasty. Two more historical sources agree with this chronology: the Abydos king list, written under Seti I and which gives Pepi I's cartouche on the 36th entry between those of Userkare and Merenre,[33] and the Turin canon, a list of kings on papyrus dating to the reign of Ramses II which records Pepi I on the fourth column, third row.[35]

Historical sources against this order of succession include the Aegyptiaca (Αἰγυπτιακά), a history of Egypt written in the 3rd century BC during the reign of Ptolemy II (283 – 246 BC) by Manetho. No copies of the Aegyptiaca have survived and it is now known only through later writings by Sextus Julius Africanus and Eusebius. According to the Byzantine scholar George Syncellus, Africanus wrote that the Aegyptiaca mentioned the succession "Othoês → Phius → Methusuphis" at the start of the Sixth Dynasty. Othoês, Phius (in Greek, φιός), and Methusuphis are believed to be the Hellenized forms for Teti, Pepi I and Merenre, respectively.[36] Manetho's reconstruction of the early Sixth Dynasty is in agreement with the Karnak king list written under Thutmosis III. The list gives Pepi's birth name immediately after that of Teti on the second row, 7th entry of the row.[37] Contrary to other sources such as the Turin canon however, the purpose of the Karnak king list was not to be exhaustive but rather to list a selection of royal ancestors to be honored. Similarly the Saqqara Tablet, written under Ramses II,[38] omits Userkare, with Pepi's name given on the 25th entry after that of Teti.[33]

Length of Reign

Pepi I's length of reign remains somewhat uncertain, although the consensus is that he ruled over Egypt for around five decades.[39]

During the Old Kingdom period, the Egyptians did not record time as we do today. Rather, they counted years since the beginning of the reign of the current king. Furthermore these years were referred to by the number of cattle counts which had taken place since the start of the reign.[40] The cattle count was an important event aimed at evaluating the amount of taxes to be levied on the population. This involved counting cattle, oxen and small livestock.[41] During the early Sixth Dynasty, this count might have been biennial,[note 3] that is occurring every two years.[40][45]

The South Saqqara Stone, a nearly contemporary royal annal dating to the reign of Pepi II, records the 25th cattle count under Pepi I, his highest known date. Accepting a biennial count, this indicates that Pepi reigned 49 years. That a 50th year of reign could have also been recorded on the royal annal cannot be discounted however, due to fragmentary state of the South Saqqara Stone.[46] Another historical source supporting such a long reign is Africanus' epitome of Manetho's Aegyptiaca, which credits Pepi I with a long reign of 53 years.[12][36] At the opposite the Turin King List gives only 20 years on the throne to Pepi I while his successor Merenre I is said to have reigned 44 years. This latter figure contradicts both contemporaneous and archaeological evidences, for example the royal annals mention no further cattle count under Merenre I beyond his fifth, which might corresponds to his tenth year of rule. The Egyptologist Kim Ryholt suggests that the two entries of the Turin king list might have been interchanged.[47]

Archaeological evidence in favor of a long reign for Pepi I include his numerous building projects and many surviving objects made in celebration his first Sed festival. For example, numerous ointment alabaster vessels celebrating Pepi's first Sed festival have been produced. They bear a standard inscriptions reading "The king of Upper and Lower Egypt Meryre, may he be given life for ever. The first occasion of the Sed festival".[48] Examples can now be found in museums throughout the world:[49][4]

Musée du Louvre

Musée du Louvre

.jpg)

The Sed festival was meant to rejuvenate the king and was first celebrated on the 30th year of a king's rule. The festival itself had a considerable importance for the king.[44] Representations of it were part of the typical decorations of temples associated to the ruler during the Old Kingdom, had the king actually celebrated it or not.[50] Further witnessing to the importance of this event, the state administration seems to have had a tendency to mention Pepi's first jubilee repeatedly in the years following its celebration and up until the end of his rule in connection with building activities. For example, Pepi's final 25th cattle count reported on the South Saqqara Stone is associated with his first Sed festival even though it likely had taken place some 19 years prior.[44]

Reign

Political situation

Acending the throne

Pepi's accession to the throne might have occurred in times of discord, as his father Teti is said by Manetho to have been assassinated by his own bodyguards.[36][7] The Egyptologist Naguib Kanawati has argued in support of Manetho's claim, noting for example that Teti's reign saw an important increase in the number of guards at the Egyptian court, with these becoming responsible for the everyday care of the king.[51] At the same time, the figures and names of several contemporary palace officials as represented in their tombs have been purposefully erased.[52] This seems to be an attempt at a damnatio memoriae[53] targeting three men in particular, the vizier Hezi[note 5], the overseer of weapons Mereri and chief physician Seankhuiptah who could therefore be behind the regicide.[55]

Pepi was by then perhaps too young a child to reign. In any case, he did not immediately succeed his father who was rather succeeded by king Userkare. Userkare's identity and relation with the royal family remains uncertain. It is possible that he served only as a regent with Pepi's mother Iput as Pepi reached adulthood,[56] or occupied the throne in the interregnum.[57] Such hypotheses are supported by the apparent lack of resistance against Pepi ultimately taking the throne.[56]

Against this view however, Kanawati has argued that Userkare's reign length—at no more than five years—is too short for a regency and that a regent would not have assumed a full royal titulary as Userkare did nor would he be included in king lists.[51] Rather, Userkare could have been an usurper and a descendant of a lateral branch of the Fifth Dynasty royal family who briefly seized power in a coup.[58] This hypothesis finds indirect evidence in Userkare's theophoric name which incorporates the name of the sun god Ra, a naming fashion common during the preceding Fifth Dynasty but which had fallen out of use since Unas' rule. Further archeological evidence lending credence to the idea that Userkare was illegitimate in the eyes of his successor Pepi I is the absence of mention of Userkare in the tombs and biographies of the many Egyptian officials who served under both Teti and Pepi I.[59][12] For example, the viziers Inumin and Khentika, who served both Teti and Pepi I, are completely silent about Userkare and none of their activities during Userkare's time on the throne are reported in their tomb.[60] Furthermore, the tomb of Mehi, a guard who lived under Teti, Userkare and Pepi, yielded an inscription showing that the name of Teti was first erased to be replaced by that of another king, whose name was itself erased and replaced again by that of Teti.[61] Kanawati argues that the intervening name was that of Userkare to whom Mehi may have transferred his allegiance.[62] Mehi's attempt to switch back to Teti was seemingly unsuccessful, as there is evidence that work on his tomb stopped abruptly and that he was never buried there.[63]

For the Egyptologist Miroslav Bárta, further troubles might have arisen directly between Pepi and relatives of his father Teti.[53] Bárta and Baud points to Pepi's decision to dismantle his paternal grandmother's queen Sesheshet funerary complex, reusing the block for his own mortuary temple.[64][53] At the same time as he apparently distanced himself from his father's line, Pepi transformed his mother's tomb into a pyramid and posthumously bestowed a new title to her, "Daughter of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt", thereby emphasizing his royal lineage as a descendant of Unas, last ruler of the Fifth Dynasty.[53]

In any case, Pepi chose the Horus name of Mery-tawy, meaning "He who is loved by the two lands" or "Beloved of the Two Lands", which Nicolas Grimal sees as a clear indication that he desired political appeasement in times of troubles.[65] Similarly, Pepi chose the throne name Nefersahor, meaning "Perfect is the protection of Horus", which he only later changed to Meryre for "Beloved of Ra", updating even the inscriptions inside his pyramid.[note 6][8] Bárta adds that Pepi's writing of his own name "Mery-tawy" is also highly unusual: he chose to inverse the order of the hieroglyphic signs composing it, placing the sign for "Beloved" before that for "Two Lands". For Bárta and Yannis Gourdon, this deliberate choice shows Pepi's deference to the powerful nobility of the country, on which he was dependent.[53] Although there seems not to be a direct relation between Userkare's brief reign and one or more later conspiracies against him, all of these events and evidences suggest some form of political instability at the time.[65]

Policies and power play

In a long trend that started earlier in the Fifth Dynasty, the Old Kingdom Egyptian state was the subject of increasing decentralization and regionalization.[67] Provincial families played an increasingly important role, marrying in the royal family, accessing the highest offices of the state administration and keeping a strong influence at the court while also consolidating their hold over regional power bases by creating true local dynasties.[68] These processes, well under way during Pepi I's reign, progressively weakened the king's primacy and ascendancy over his own administration and would ultimately result in the princedoms of the First Intermediate Period.[69] Pepi seems to have developed several policies to counteract this, notably with the constructions of royal Ka chapels throughout Egypt,[69][70] to strengthen the royal presence in the provinces.[71] These expensive policies suggest that Egypt was prosperous during Pepi's reign.[35] The concurrent rise of small provincial centers in areas historically associated with the crown may prove that pharaohs of the Sixth Dynasty tried to diminish the power of predominant regional dynasties by recruiting senior officials outside of them.[72] Some of these new officials have no known background, indicated that they were not of noble extraction. The circulation of high officials in key positions of power occurred at an "astonishing" pace under Teti and Pepi I according to the Egyptologist Juan Carlos Moreno García,[68] in what might have been a deliberate attempt at curtailing the concentration of power in the hands of few officials.[73]

Teti and Pepi I changed the organization of the territorial administration as well: many provincial governors were nominated, especially in Upper Egypt,[73] while Lower Egypt was possibly under direct royal administration.[74] Agricultural estates affiliated to the crown in the provinces during the preceding dynasty were replaced by novel administrative entities, the ḥwt, which were agricultural centers controlling tracts of land, livestock and workers. Together with temples and royal domains, the numerous ḥwt represented a network of warehouses accessible to royal envoys and from which taxes and labor could easily be collected.[75] This territorial mode of organization disappeared nearly 300 years after Pepi I's reign, at the dawn of the Middle Kingdom period.[75]

In parallel with these developments, Pepi decreed tax-exemptions to various institutions. He gave such an exemption to the Ka-chapel of his mother located in Koptos.[note 7][76] Another decree has survived on a stela discovered near the Bent Pyramid in Dashur, whereby in his 21st year of reign, Pepi grants exemptions to the people serving in the two pyramids of Sneferu:[77]

My majesty has commanded that these two pyramid towns be exempt for him throughout the course of eternity from doing any work of the palace, from doing any forced labor for any part of the royal residence throughout the course of eternity, or from doing any forced labor at the word of anybody in the course of eternity.[78]

The Egyptologist David Warburton sees such perpetual tax exemptions as a capitulation on behalf of a benevolent king confronted with rampant corruption. Be they the result of religious or political motives, exemptions created a precedent which not only encouraged other institutions to request a similar treatment but they durably weakened the power of the state as they accumulated over time.[79]

Conspiracies

At some point in his reign, either early[35] or late, around his 44th year on the throne,[28] Pepi faced a conspiracy hatched by one of his harem consort, only known from her queenly tile "Weret-Yamtes". Although the precise nature of her crime is not reported by Weni who served as a judge during the subsequent trial, this at least shows that the person of the king was not untouchable anymore.[80] According to Hans Goedicke, who read Weret-Yamtes as proper name, she could have been the mother of Merenre.[28] Nicolas Grimal[note 8] and Baud see this as highly unlikely and outright extravagant respectively,[81] as this queen's son would have been punished together her.[27] Perhaps in response to these events, late in his reign Pepi married two daughters of Khui, nomarch of Abydos.[82] This may also have served to counteract the weakening of the king's authority over Middle and Upper Egypt by securing the allegiance of a powerful family.[83]

The political importance of this marriage is suggested by the fact that, for the first and last time until the 26th Dynasty some 1800 years later, Khui's wife Nebet, a woman, bore the title of vizier of Upper Egypt, a charge which may be purely honorific[84] or which she may have really assumed.[52] Later, Khui's and Nebet's son Djau was made vizier as well. Pepi's marriages might be at the origin[85] of a trend, which continued during the later Sixth and Eighth Dynasties, in which the temple of Min in Koptos was the focus of much royal patronage.[28] This is manifested by the Coptos Decrees, which record successive pharaohs granting tax exemptions to the temple as well as official honors bestowed by the kings to the local ruling family while the Old Kingdom society was collapsing.[86]

This part of Pepi's rule may not have been any less troubled than his early reign, as Kanawati conjectures that Pepi faced yet another conspiracy against him, in which his vizier Rawer could have been involved. To support his theory, Kanawati observes that Rawer's image in his tomb has been desecrated, with his name, hands and feet chiselled off, while this same tomb is dated to the second half of Pepi's reign on stylistic grounds.[87] Kanawati further posits that the conspiracy may have aimed at having someone else designated heir to the throne at the expense of Merenre. Consequently to the failure of this conspiracy, Pepi I would have taken the drastic step of crowning Merenre during his own reign,[39] thereby creating the earliest documented coregency of the history of Egypt.[87] That such a coregency did indeed take place is indirectly supported by a gold pendant bearing the names of both Pepi I and Merenre I as kings,[88] an inscription mentioning king Merenre in Hatnub which suggests that he counted his years of reign starting at some point during his father's reign and the copper statues of Hierakonpolis, discussed below.[83]

Trade, mining and military activities

Trade and mining

Much of the trade with settlements along the Levantine coast which had existed during the earlier Fifth Dynasty not only continued but seem to have peaked[89] under Pepi I and Pepi II. The chief trade partner there might have been Byblos, where dozens of inscriptions showing Pepi's cartouches have been found,[90] as well as a large alabaster vessel bearing Pepi's titulary and commemorating his jubilee from the Temple of Baalat Gebal.[91] Through Byblos, Egypt had indirect contacts[92] took place with the city of Ebla in modern-day Syria.[93] The latter is established by alabaster vessels[94] bearing Pepi's name found near Ebla's royal palace G,[note 9][96] destroyed in the 23rd century BC.[97] Trading parties departed Egypt for the Levant from a Nile Dela port called Ra-Hat, "the first mouth [of the Nile]". This trade benefited the nearby city of Mendes, from which one of Pepi's vizier likely originated.[98] At the same time, an extensive network of caravan routes traversed Egypt's Western Desert, for example from Abydos to the Kharga Oasis and from there to the Dakhla and Selima Oases.[93]

Expeditions and mining activities that were already taking place in the Fifth and early Sixth Dynasty continued unabated. These include at least one expedition to the mines of turquoise and copper in Wadi Maghareh, Sinai, [93] circa Pepi's 36th year on the throne,[57] an expedition to Hatnub, where alabaster was extracted[93] at least once on Pepi's 49th year of reign,[57] as well as visits to the Gebel el-Silsila[99] and Sehel Island.[100] Greywacke and siltstone for building projects originated from quarries of the Wadi Hammamat,[93] where Pepi I is mentioned in circa eighty graffiti.[101]

Military campaigns

Militarily, Pepi I's reign was marked by aggressive expansion into Nubia.[102][103] This is reported on the walls of the tombs of the contemporary nomarchs of Elephantine,[102] by alabaster vessels bearing Pepi's cartouche found in Kerma[104] and by inscriptions in Tumas.[57] To the north-east of Egypt, Pepi launched at least five military expeditions against the "sand dwellers"[note 10] of Sinai and southern Palestine.[83][106] These campaigns are recounted on the walls of the tomb of Weni, then officially a palace superintendent but given the task of a general.[107] Weni tells how he ordered nomarchs in Upper Egypt and the Nile Delta region to "call up the levies of their own subordinates, and these in turn summoned their subordinates down through every level of the local administration".[108] Meanwhile, Nubian mercenaries were also recruited,[note 11][83] so that in total tens of thousands of men were at Weni's disposal.[107] This is the only text relating the raising of an Egyptian army during the Old Kingdom period,[108] and it also indirectly reveals the absence of a permanent, standing army at the time.[110] The goal of this army was either to repulse and push-back rebelling Bedouins[111] and Semitic people[note 12] or to seize their properties and conquer their land in southern Palestine or, less likely,[113] in the Eastern Nile Delta.[114] In any case the Egyptians did invade their opponents up to what was probably Mount Carmel[113] or Ras Kouroun,[115] landing troops directly on the coast thanks to Egyptian transport boats.[83][116] Weni reports the destruction of walled towns, cutting down fig-trees and grape vines and setting fire to local shrines.[117]

Building activities

Pepi I built extensively throughout Egypt,[118] so much so that the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie considered in 1900 that "this king has left more monuments, large and small, than any other ruler before the Twelfth Dynasty".[35] A similar conclusion is reached by the Egyptologist Jean Leclant who sees Pepi's rule as marking the apogee of the Old Kingdom period owing to the flurry of building activities, administrative reforms, trade and military campaigns at the time.[12] Pepi's building efforts were mostly devoted to local cults[116] and royal Ka chapels,[119] seemingly with the objective of affirming the king's stature and presence in the provinces.[120]

Ka chapels

Ka-chapels comprised one or more chambers for the bringing of offerings dedicated to the cult of the Ka of a deceased or, in this case, of the king.[121] Such chapels dedicated to Pepi I were uncovered or are known from comtemporary sources to have stood in Hierakonpolis,[122][123] in Abydos, [124][125] in Bubastis[126] and in the central Nile Delta region,[127] in Memphis, Zawyet el-Meytin, Assiut, Qus[119] and beyond the Nile Valley in Balat, a settlement of the Dakhla Oasis.[128] A further chapel might have existed in Elkab where rock inscriptions refer to his funerary cult.[129] All of these were likely peripheral to or inside larger temples hosting extensive cult activities,[130][131] for example that at Abydos was likely next to the temple of Khenti-Amentiu.[132]

Beneath the floor of Hierakonpolis Ka-chapel of Pepi, in an underground store, James Quibell uncovered a statue of king Khasekhemwy of the Second Dynasty, a terracota lion cub made during the Thinite era,[133] a golden mask representing Horus and two copper statues.[134] These statues, originally fashioned by hammering plates of copper over a wooden base[134][135] had been disassembled and placed inside one another then sealed with a thin layer of engraved copper bearing the titles and names of Pepi I "on the first day of the Heb Sed" feast.[133] The two statues were symbolically "trampling underfoot the Nine bows"—the enemies of Egypt—a stylized representation of Egypt's conquered foreign subjects.[14] While the identity of the larger adult figure as Pepi I is revealed by the inscription, the identity of the smaller statue showing a younger person remains unresolved.[133] The most common hypothesis among Egyptologists is that the young man shown is Merenre:[123] "who was publicly associated as his father's successor on the occasion of the Jubilee [the Heb Sed feast]. The placement of his copper effigy inside that of his father would therefore reflect the continuity of the royal succession and the passage of the royal sceptre from father to son before the death of the pharaoh could cause a dynastic split."[136] Alternatively, Bongioanni and Croce have also proposed that the smaller statue may represent "a more youthful Pepy I, reinvigorated by the celebration of the Jubilee ceremonies."[137]

Temples

The close association between Ka-chapels and temples might have spurred building activities for the latter as well. For example, the Bubastis ensemble of Pepi I comprised a 95 m × 60 m (312 ft × 197 ft) enclosure wall and, near its north corner, the small Ka-chapel made of rectangular building housing 8 pillars.[138] This ensemble was peripheral to the main Old Kingdom temple dedicated to the goddess Bastet.[123] In Dendera, where a fragmentary statue of a seated Pepi I has been uncovered,[139] Pepi restored the temple complex to the goddess Hathor.[140] In Abydos,[141] he built a small rock cut chapel dedicated to the local god Khenti-Amentiu,[142] where he is referred to as "Pepi, Son of Hathor of Dendera".[143] Pepi also referred to himself as the son of Atum of Heliopolis, a direct evidence of the consolidation of the Heliopolitan cults at the time.[144]

At the southern border of Egypt, in Elephantine, several faience plaques bearing Pepi's cartouche[145] have been uncovered in the temple of Satet. These may witness royal interest in the local cult.[85] An alabaster statue of an ape with its offspring bearing Pepi I's cartouche[146] was also uncovered in the same location, but it was rather probably a gift of the king to a high official who then dedicated it to Satet.[71] In this temple that Pepi built a red granite naos[71] meant either to house the goddess’s statue[147] or a statue of Pepi I himself, making the naos into yet another Ka-chapel.[148] The naos, which stands 1.32 m (4.3 ft) high is inscribed with Pepi I's cartouche and the epithet "beloved of Satet".[71] Pepi seems to have undertaken wider works in the temple, possibly reorganizing its layout by adding walls and an altar.[149] In this context, the faience tablets bearing his cartouche may be foundation offerings made at the start of the works,[150] although this has been contested.[151] For the Egyptologist David Warburton, the reigns of Pepi I and II mark the first period during which small stone temples dedicated to local gods were built in Egypt.[144]

Other projects

Further building activities may be inferred from the inscriptions in the tomb of Nekhebu, a high official belonging to the family of Senedjemib Inti, a vizier during the late Fifth Dynasty. Nekhebu reports overseeing the excavations of canals in Lower Egypt and at Cusae in Middle Egypt.[127][152]

Pyramid complex

Pepi I had a pyramid built for himself in South Saqqara,[153] which he named Men-nefer-Pepi variously translated as "Pepi's splendor is enduring",[154] "The perfection of Pepi is established"[155] "The beauty of Pepi endures",[2] and "The perfection of Pepi endures".[156] The diminutive name Mennefer for the pyramid complex gave rise to a novel designation for the nearby capital of Egypt originally called Ineb-hedj, designation which ultimately gave Memphis in Greek.[2][156][14]

Pepi's main pyramid was constructed in the same fashion as others since Djedkare Isesi:[157] a core built six steps high from small roughly dressed blocks of limestone bound together using clay mortar encased with fine limestone blocks.[158] The pyramid, now destroyed, had a base length of 78.75 m (258 ft; 150 cu) converging to the apex at ~ 53° and once stood 52.5 m (172 ft; 100 cu) tall.[155] Its remains now form a mound a meagre 12 m (39 ft; 23 cu),[154][153] containing a pit in its centre dug by stone thieves.[159]

The substructure of the pyramid was accessed from the north chapel which has since disappeared. From the entrance, a descending corridor gives way to a vestibule leading into the horizontal passage. Halfway along the passage three granite portcullises guard the chambers. As in preceding pyramids, the substructure contains three chambers: an antechamber on the pyramids vertical axis, a serdab with three recesses to its east, and a burial chamber containing the king's sarcophagus to the west.[160] Extraordinarily, the pink granite canopic chest that is sunk into the floor at the foot of the sarcophagus has remained undisturbed.[155][161] Discovered alongside it was a bundle of viscera presumed to belong to the pharaoh.[161] The provenance of a mummy fragment and fine linen wrappings discovered in the burial chamber are unknown, but are hypothesized to belong to Pepi I.[162]

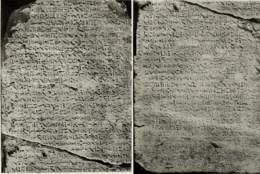

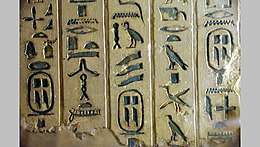

The walls of Pepi I's antechamber, burial chamber, and much of the corridor[note 13] are covered in vertical columns of inscribed hieroglyphic text,[166][162][155] painted green with ground malachite and gum arabic, a color symbolizing renewal.[167] His sarcophagus is also inscribed on its east side with the king's titles and names, as part of a larger set of spells that includes texts at the bottom of the north and south walls opposite the sarcophagus, and in a line running across the top of the north, west, and south walls of the chamber.[168] The writing comprises 2,263 columns and lines of text, making them the most extensive corpus of Pyramid Texts from the Old Kingdom.[169] The tradition of inscribing texts inside the pyramid was begun by Unas at the end of the Fifth Dynasty,[170][171][2] but originally discovered in Pepi I's pyramid in 1880.[172][155] Their function, in congruence with all funerary literature, was to enable the reunion of the ruler's ba and ka leading to the transformation into an akh,[173][174] and to secure eternal life among the gods in the sky.[175][176][177]

Legacy

Pepi I was the object of a funerary cult after his death with ritual activities taking place in his funerary complex. Archaeological evidence show that these activities continued throughout the end of the third millenium BC until the early Middle Kingdom period, covering the First Intermediate Period, a period during which the Egyptian state likely collapsed.[178]

The consequences of the long lasting cults of Old Kingdom pharaohs during the New Kingdom period is apparent in the Karnak king list dating to Thutmosis III's reign. Several pharaohs of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasty including Nyuserre Ini, Djedkare Isesi, Teti and Pepi I are mentioned on the list by their birth name, rather than throne name. For the Egyptologist Antonio Morales, this is because of popular cults for these kings which existed well into the New Kingdom and which referred to these kings using their birth name.[179]

Notes

- Dates proposed for Pepi I's reign: 2390–2361 BC,[1] 2354–2310 BC,[2][3] 2338–2298 BC,[4] 2335–2285 BC,[5] 2332–2283 BC,[6] 2321–2287 BC,[7][8] 2289–2255 BC,[9] 2285–2235 BC,[5] 2276–2228 BC.[10]

- They were also named Ankhesenmeryre I and II.[25]

- There has been some doubt regarding whether the cattle count dating system was strictly biennial or slightly more irregular early in the Sixth Dynasty. That the latter situation appeared to be the case was suggested by the "Year after the 18th Count, 3rd Month of Shemu day 27" inscription from Wadi Hammamat No. 74-75 which mentions the "first occurrence of the Heb Sed" in that year for Pepi. Normally, the Sed festival is first celebrated in a king's 30th year of reign while the 18th cattle count would have taken place in his 36th year, had it been strictly biennial.[42] The Egyptologist Michel Baud has points to

a similar inscription dated to "Year after the 18th Count, 4th Month of Shemu day 5" in Sinai graffito No. 106.[43] This could imply that the cattle count during the Sixth Dynasty was not regularly biennial or that it was continuously referenced in the years following it. Michel Baud stresses that the year of the 18th count is preserved in the South Saqqara Stone and writes that:

- "Between the mention of count 18 [here] and the next memorial formula which belongs to count 19, end of register D, the available space for count 18+ is the expected half of the average size of a theoretical [year count] compartment. It is hard to believe that such a narrow space corresponds to the jubilee celebration, which obviously had a considerable importance for this (and every) king."[44]

- catalog number 39.121

- Because of a typo in Hubschmann 2011 [54] vizier Hezi became also known as “Heri” in various texts.

- At this point, the Ancient Egyptian royal titulary assumed its definitive standard form.[53]

- The decree recording this, called decree Coptos Decree (a) in modern Egyptology, is now in the Egyptian Museum Cairo, catalog number 41890.[76]

- Like Hans Goedicke, Nicolas Grimal also read Weret Yamtes as a proper name rather than a title[27] but this is strongly opposed by others including Michel Baud.[81]

- For example, an alabaster lid of a precious vessel is inscribed with "Beloved of the two lands, king of Upper and Lower Egypt, the son of Hathor, lady of Dendera, Pepi". As Hathor was the chief deity of Byblos, it is likely that this vessel was destined to this city and was only later exchanged or given to Ebla.[95]

- Transliteration from Ancient Egyptian ḥryw-š.[105]

- The Dashur decree of Pepi I shows that such mercenaries were already integrated into Egyptian society, for example in pyramid towns, where they served as soldiers.[109]

- Transliteration from Ancient Egyptian 3'mu often translated "Semite".[112]

- The corridor texts in Pepi I's pyramid are the most extensive, covering the whole horizontal passage, the vestibule, and even a section of the descending corridor.[163][164] Unas' pyramid constrained the texts to the south section of the corridor,[165] as did Teti's.[163] The texts in Merenre I's and Pepi II's pyramids covered the entire corridor and the vestibule.[163]

References

- Wright & Pardee 1988, p. 144.

- Verner 2001b, p. 590.

- Altenmüller 2001, p. 602.

- Brooklyn Museum 2020.

- von Beckerath 1997, p. 188.

- Clayton 1994, p. 64.

- Rice 1999, p. 150.

- Málek 2000a, p. 104.

- MET Cylinder 2020.

- Hornung 2012, p. 491.

- Leprohon 2013, p. 42.

- Allen et al. 1999, p. 10.

- Leprohon 2013, p. 236.

- Grimal 1992, p. 84.

- Dodson & Hilton 2004, pp. 64 – 65 & 76.

- Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 76.

- Baud 1999b, p. 410.

- Baud 1999b, p. 411.

- Baud 1999b, p. 471.

- Baud 1999b, p. 483.

- Baud 1999b, p. 415.

- Leclant 1999, p. 866.

- Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 73.

- Baud 1999b, pp. 625–626.

- Baud 1999b, pp. 426–429.

- Strudwick 2005, p. 353.

- Grimal 1992, pp. 82–83.

- Goedicke 1955, p. 183.

- Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 78.

- Baud 1999b, pp. 506–507.

- Baud 1999b, p. 412.

- Baud 1999b, p. 413.

- von Beckerath 1997, p. 27.

- von Beckerath 1999, pp. 62–63, king number 3.

- Baker 2008, p. 293.

- Waddell 1971, p. 53.

- Morales 2006, p. 320, footnote 30.

- Daressy 1912, p. 205.

- Bárta 2017, p. 11.

- Gardiner 1945, pp. 11–28.

- Katary 2001, p. 352.

- Spalinger 1994, p. 303.

- Baud 2006, p. 148.

- Baud 2006, p. 150.

- Verner 2001a, p. 364.

- Baud & Dobrev 1995, pp. 46–49.

- Ryholt 1997, pp. 13–14.

- Strudwick 2005, pp. 130–131.

- Allen et al. 1999, pp. 446–449.

- Verner 2001a, p. 404.

- Kanawati 2003, p. 184.

- Kanawati 2003, p. 173.

- Bárta 2017, p. 10.

- Hubschmann 2011.

- Hubschmann 2011, p. 2.

- Grimal 1992, p. 81.

- Smith 1971, p. 191.

- Baker 2008, p. 487.

- Kanawati 2003, p. 95.

- Kanawati 2003, p. 89.

- Kanawati 2003, pp. 94–95.

- Kanawati 2003, p. 163.

- Kanawati 2003, p. 164.

- Baud 1999b, pp. 558 & 562–563.

- Grimal 1992, p. 82.

- MET Cylinder 2020, catalog number 17.5.

- Tyldesley 2019, p. 57.

- Moreno García 2013, p. 122.

- Bussmann 2007, p. 16.

- Fischer 1958, pp. 330–333.

- Bussmann 2007, p. 17.

- Moreno García 2013, p. 123.

- Moreno García 2013, p. 124.

- Moreno García 2013, pp. 125 & 132.

- Moreno García 2013, p. 129.

- Hayes 1946, p. 4.

- Edwards 1999, p. 253.

- Redford 1992, p. 61.

- Warburton 2012, p. 79.

- Málek 2000a, p. 105.

- Baud 1999b, p. 626.

- Málek 2000a, pp. 104–105.

- Smith 1971, p. 192.

- Baud 1999b, p. 630.

- Yurco 1999, p. 240.

- Hayes 1946, pp. 3–23.

- Kanawati 2003, p. 177.

- Allen et al. 1999, p. 11.

- Wright & Pardee 1988, p. 294.

- Baker 2008, p. 294.

- Wright & Pardee 1988, p. 149.

- Matthiae 1978, pp. 230–231.

- Málek 2000a, p. 106.

- Redford 1992, p. 41.

- Matthiae 1978, pp. 230–232.

- Matthiae 1978, pp. 230–231, fig. 20.

- Astour 2002, p. 60.

- Moreno García 2013, p. 133.

- Smith 1999, p. 394.

- Petrie 1897, p. 89.

- Meyer 1999, p. 1063.

- Hayes 1978, p. 122.

- Encyclopædia Britannica 2020, Pepi I, king of Egypt.

- Smith 1971, p. 194.

- Goedicke 1963, p. 188.

- Hayes 1978, p. 125.

- Redford 1992, p. 54.

- Schulman 1999, p. 166.

- Spalinger 2013, p. 448.

- Kanawati 2003, p. 1.

- Redford 1992, p. 55.

- Goedicke 1963, p. 189.

- Wright & Pardee 1988, p. 154.

- Goedicke 1963, pp. 189–197.

- Helck 1971, p. 18.

- Hayes 1978, p. 126.

- Goedicke 1963, p. 190.

- Breasted & Brunton 1924, p. 27.

- Bussmann 2007, pp. 16–17.

- Bussmann 2007, p. 20.

- Bolshakov 2001, p. 217.

- O'Connor 1992, pp. 91–92, fig. 5A.

- Brovarski 1994, p. 18.

- Brovarski 1994, p. 17.

- Kraemer 2017, p. 20.

- Lange 2016, p. 121.

- Moreno García 2013, p. 134.

- Pantalacci 2013, p. 201.

- Hendrickx 1999, p. 344.

- O'Connor 1992, pp. 84, 87, 96.

- Moreno García 2013, p. 127.

- Brovarski 1994, p. 19.

- Bongioanni & Croce 2001, p. 84.

- Muhly 1999, p. 630.

- Peck 1999, p. 875.

- Bongioanni & Croce 2001, pp. 84–85.

- Bongioanni & Croce 2001, p. 85.

- Warburton 2012, p. 127.

- Daumas 1952, pp. 163–172.

- Cauville 1999, p. 298.

- O'Connor 1999, p. 110.

- Kraemer 2017, p. 13.

- Kraemer 2017, p. 1.

- Warburton 2012, p. 69.

- Dreyer 1986, no. 428–447.

- Dreyer 1986, no. 455.

- Kaiser 1999, p. 337.

- Franke 1994, p. 121.

- Bussmann 2007, pp. 17–18.

- Dreyer 1986, p. 94.

- Bussmann 2007, p. 18.

- Strudwick 2005, pp. 265–266.

- Lehner 2008, p. 157.

- Verner 2001d, p. 351.

- Lehner 2008, p. 158.

- Altenmüller 2001, p. 603.

- Verner 2001d, p. 352.

- Verner 2001d, pp. 325 & 352–353.

- Lehner 2008, pp. 157–158.

- Verner 2001d, pp. 353–354.

- Hellum 2007, p. 107.

- Verner 2001d, p. 354.

- Allen 2005, p. 12.

- Hays 2012, p. 111.

- Lehner 2008, p. 154.

- Hayes 1978, p. 82.

- Leclant 1999, p. 867.

- Allen 2005, p. 97 & 100.

- Allen 2005, p. 97.

- Málek 2000a, p. 102.

- Allen 2001, p. 95.

- Verner 2001d, pp. 39–40.

- Allen 2005, pp. 7–8.

- Lehner 2008, p. 24.

- Verner 1994, p. 57.

- Grimal 1992, p. 126.

- Hays 2012, p. 10.

- Moreno García 2015, p. 5–6.

- Morales 2006, p. 320.

Bibliography

- Allen, James; Allen, Susan; Anderson, Julie; Arnold, Arnold; Arnold, Dorothea; Cherpion, Nadine; David, Élisabeth; Grimal, Nicolas; Grzymski, Krzysztof; Hawass, Zahi; Hill, Marsha; Jánosi, Peter; Labée-Toutée, Sophie; Labrousse, Audran; Lauer, Jean-Phillippe; Leclant, Jean; Der Manuelian, Peter; Millet, N. B.; Oppenheim, Adela; Craig Patch, Diana; Pischikova, Elena; Rigault, Patricia; Roehrig, Catharine H.; Wildung, Dietrich; Ziegler, Christiane (1999). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. OCLC 41431623.

- Allen, James (2001). "Pyramid Texts". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 95–98. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Allen, James (2005). Der Manuelian, Peter (ed.). The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Writings from the Ancient World, Number 23. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-182-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (2001). "Old Kingdom: Fifth Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 597–601. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Astour, Michael C. (2002). "A Reconstruction of the History of Ebla (Part 2)". In Gordon, Cyrus H.; Rendsburg, Gary A. (eds.). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language. 4. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-1-57506-060-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baker, Darrell (2008). The Encyclopedia of the Pharaohs: Volume I - Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty 3300 – 1069 BC. London: Stacey International. ISBN 978-1-905299-37-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bárta, Miroslav (2017). "Radjedef to the Eighth Dynasty". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.

- Baud, Michel; Dobrev, Vassil (1995). "De nouvelles annales de l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Une "Pierre de Palerme" pour la VIe dynastie". Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in French). 95: 23–92. ISSN 0255-0962.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baud, Michel (1999a). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 1 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/1 (in French). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baud, Michel (1999b). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 2 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/2 (in French). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baud, Michel (2006). "The Relative Chronology of Dynasties 6 and 8". In Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Brill.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bolshakov, Andrey (2001). "Ka-Chapel". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 217–219. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bongioanni, Alessandro; Croce, Maria, eds. (2001). The Treasures of Ancient Egypt: From the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Universe Publishing, a division of Ruzzoli Publications Inc.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Breasted, James Henry; Brunton, Winifred (1924). Kings and queens of ancient Egypt. London: Hodder & Stoughton. OCLC 251195519.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brooklyn Museum (2020). "Vase of Pepi I". Brooklyn Museum.

- Brovarski, Edward (1994). "Abydos in the Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period, Part II". In Silverman, David P. (ed.). For His Ka: Essays Offered in Memory of Klaus Baer. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization. 55. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. pp. 15–45. ISBN 0-918986-93-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bussmann, Richard (2007). "Pepi I and the Temple of Satet at Elephantine". In Mairs, Rachel; Stevenson, Alice (eds.). Current Research in Egyptology 2005. Proceedings of the Sixth Annual Symposium, University of Cambridge, 6-8 January 2005 (PDF). Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 16–21. JSTOR j.ctt1cd0npx.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cauville, Sylvie (1999). "Dendera". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Blake Shubert, Steven (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. pp. 298–301. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daressy, Georges (1912). "La Pierre de Palerme et la chronologie de l'Ancien Empire". Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in French). 12: 161–214. ISSN 0255-0962. Retrieved 2018-08-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daumas, François (1952). "Le trône d'une statuette de Pépi Ier trouvé à Dendara [avec 3 planches]". Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in French). 52: 163–172.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05128-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dreyer, Günter (1986). Elephantine, 8: Der Tempel der Satet. Die Funde der Frühzeit und des Alten Reiches. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen (in German). 39. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. ISBN 3-80-530501-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edwards, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen (1999). "Dahshur, the Northern Stone Pyramid". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Blake Shubert, Steven (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. pp. 252–254. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fischer, H.G. (1958). "Review of L.Habachi Tell Basta". American Journal of Archaeology. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archeologie Orientale du Caire. 62: 330–333. doi:10.2307/501964. JSTOR 501964.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Franke, Detlef (1994). Das Heiligtum des Heqaib auf Elephantine. Geschichte eines Provinzheiligtums im Mittleren Reich. Studien zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altägyptens (in German). 9. Heidelberg: Heidelberger Orientverlag. ISBN 3-92-755217-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gardiner, Alan (1945). "Regnal Years and Civil Calendar in Pharaonic Egypt". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 31: 11–28. doi:10.1177/030751334503100103. JSTOR 3855380.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goedicke, Hans (1955). "The Abydene Marriage of Pepi I". Journal of the American Oriental Society. Ann Arbor: American Oriental Society. 75 (3): 180–183. doi:10.2307/595170. JSTOR 595170.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goedicke, Hans (1963). "The alleged military campaign in southern Palestine in the reign of Pepi I (VIth Dynasty)". Rivista degli studi orientali. Rome: Sapienza, Universita di Roma. 38 (3): 187–197. JSTOR 41879487.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Oxford: Blackwell publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hays, Harold M. (2012). The Organization of the Pyramid Texts: Typology and Disposition (Volume 1). Probleme der Ägyptologie. 31. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-22749-1. ISSN 0169-9601.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hayes, William C. (1946). "Royal decrees from the temple of Min at Coptus". Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 32: 3–23. doi:10.1177/030751334603200102. JSTOR 3855410.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hayes, William (1978). The Scepter of Egypt: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. OCLC 7427345.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Helck, Wolfgang (1971). Die Beziehungen Ägyptens zu Vorderasien im 3. und 2. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Ägyptologische Abhandlungen (in German). 5 (2nd ed.). Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 3-44-701298-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hellum, Jennifer (2007). The Pyramids. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313325809.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hendrickx, Stan (1999). "Elkab". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Blake Shubert, Steven (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. pp. 342–346. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David, eds. (2012). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5. ISSN 0169-9423.

- Hubschmann, Caroline (2011). "Naguib Kanawati, Conspiracies in the Egyptian Palace: Unis to Pepy I" (PDF). Eras. Melbourne: Monash University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaiser, Werner (1999). "Elephantine". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Blake Shubert, Steven (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. pp. 335–342. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kanawati, Naguib (2003). Conspiracies in the Egyptian Palace: Unis to Pepy I. Oxford and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-61937-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Katary, Sally (2001). "Taxation". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 351–356. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kraemer, Bryan (2017). "A shrine of Pepi I in South Abydos". Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 103 (1): 13–34. doi:10.1177/0307513317722450.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lange, Eva (2016). "Die Ka-Anlage Pepis I. in Bubastis im Kontext königlicher Ka-Anlagen des Alten Reiches". Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde (in German). 133 (2): 121–140.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leclant, Jean (1999). "Saqqara, pyramids of the 5th and 6th Dynasties". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Blake Shubert, Steven (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. pp. 865–868. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary. Volume 33 of Writings from the ancient world. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-589-83736-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Málek, Jaromir (2000a). "The Old Kingdom (c.2686-2160 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. pp. 104. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Matthiae, Paolo (1978). "Recherches archéologiques à Ébla, 1977: le quartier administratif du palais royal G". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 122 (2): 204–236.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (2020). "Cylinder Seal with the Name of Pepi I ca. 2289–2255 B.C." Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Meyer, Carol (1999). "Wadi Hammamat". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Blake Shubert, Steven (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. pp. 1062–1065. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morales, Antonio J. (2006). "Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005, Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague (June 27–July 5, 2005). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 311–341. ISBN 978-80-7308-116-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moreno García, Juan Carlos (2013). "The Territorial Administration of the Kingdom in the 3rd Millennium". In Moreno García, Juan Carlos (ed.). Ancient Egyptian administration. Leiden, Boston: Brill. pp. 85–152. ISBN 978-90-04-24952-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moreno García, Juan Carlos (2015). "Climatic change or sociopolitical transformation? Reassessing late 3rd millennium BC in Egypt". 2200 BC: ein Klimasturz als Ursache für den Zerfall der Alten Welt? 7. Mitteldeutscher Archäologentag, vom 23. bis 26. Oktober 2014 in Halle (Saale); 2200 BC: a climatic breakdown as a cause for the collapse of the old world? 7th Archaeological Conference of Central Germany, October 23-26, 2014 in Halle (Saale). Tagungen des Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte Halle (Saale). 13. Halle (Saale): Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt, Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-8-44-905585-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Muhly, James (1999). "Metallurgy". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Blake Shubert, Steven (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. pp. 628–634. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Connor, David (1992). "The Status of Early Egyptian Temples: An Alternative Theory". In Friedman, Renée; Adams, Barbara (eds.). The Followers of Horus: Studies Dedicated to Michael Allen Hoffman (1944-1990). Oxbow Monograph; Egyptian Studies Association Publication. 20. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 83–98. OCLC 647981227.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Connor, David (1999). "Abydos, North, ka chapels and cenotaphs". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Blake Shubert, Steven (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. pp. 110–113. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pantalacci, Laure (2013). "Balat, A Frontier Town and its Archive". In Moreno García, Juan Carlos (ed.). Ancient Egyptian administration. Leiden, Boston: Brill. pp. 197–214. ISBN 978-90-04-24952-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peck, William H. (1999). "Sculpture, production techniques". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Blake Shubert, Steven (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. pp. 874–876. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Pepi I king of Egypt". Encyclopædia Britannica. 20 July 1998. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Petrie, Flinders (1897). A history of Egypt. Volume I: From the earliest times to the XVIth dynasty (Third ed.). London: Methuen & Co. OCLC 265478912.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Redford, Donald (1992). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-03606-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rice, Michael (1999). Who is who in Ancient Egypt. Routledge London & New York. ISBN 978-0-203-44328-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ryholt, Kim (1997). The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period c. 1800–1550 B.C. CNI publications. 20. Copenhagen: The Carsten Niebuhr Institute of Near Eastern Studies: Museum Tusculam Press. ISBN 87-7289-421-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schulman, Alan (1999). "Army". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Blake Shubert, Steven (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. pp. 165–167. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, William Stevenson (1971). "The Old Kingdom of Egypt and the Beginning of the First Intermediate Period". In Edwards, I. E. S.; Gadd, C. J.; Hammond, N. G. L. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 1, Part 2. Early History of the Middle East (3rd ed.). London, New york: Cambridge University Press. pp. 145–207. ISBN 9780521077910. OCLC 33234410.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Mark (1999). "Gebel el-Silsila". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Blake Shubert, Steven (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. pp. 394–397. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spalinger, Anthony (1994). "Dated Texts of the Old Kingdom". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag GmbH. 21: 275–319. JSTOR 25152700.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spalinger, Anthony (2013). "The Organisation of the Pharaonic Army (Old to New Kingdom)". In Moreno García, Juan Carlos (ed.). Ancient Egyptian administration. Leiden, Boston: Brill. pp. 393–478. ISBN 978-90-04-24952-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Strudwick, Nigel C. (2005). Texts from the Pyramid Age. Writings from the Ancient World (book 16). Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-680-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2019). The pharaohs. London: Quercus. ISBN 978-1-52-940451-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verner, Miroslav (1994). Forgotten Pharaohs, Lost Pyramids: Abusir (PDF). Prague: Academia Škodaexport. ISBN 978-80-200-0022-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-01.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verner, Miroslav (2001a). "Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology" (PDF). Archiv Orientální. 69 (3): 363–418.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verner, Miroslav (2001b). "Old Kingdom". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 585–591. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verner, Miroslav (2001d). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1703-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1997). Chronologie des pharaonischen Ägypten : die Zeitbestimmung der ägyptischen Geschichte von der Vorzeit bis 332 v. Chr. Münchner ägyptologische Studien (in German). 46. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-2310-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. Münchner ägyptologische Studien (in German). Mainz: Philip von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-2591-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waddell, William Gillan (1971). Manetho. Loeb classical library, 350. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press; W. Heinemann. OCLC 6246102.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Warburton, David (2012). Architecture, power, and religion : Hatshepsut, Amun & Karnak in context. Beiträge zur Archäologie. 7. Münster: Lit Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3-64-390235-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wright, Mary; Pardee, Dennis (1988). "Literary Sources for the History of Palestine and Syria: Contacts between Egypt and Syro-Palestine during the Old Kingdom". The Biblical Archaeologist. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The American Schools of Oriental Research. 51 (3): 143–161. doi:10.2307/3210065. JSTOR 3210065.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yurco, Frank J. (1999). "Cult temples prior to the New Kingdom". In Bard, Kathryn A.; Blake Shubert, Steven (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. New York: Routledge. pp. 239–242. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)