Psamtik I

Wahibre Psamtik I (Ancient Egyptian: wꜣḥ-jb-rꜥ psmṯk, known by the Greeks as Psammeticus or Psammetichus (Latinization of Ancient Greek: Ψαμμήτιχος, romanized: Psammḗtikhos), who ruled 664–610 BC, was the first of three kings of that name of the Saite, or Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt.

| Psamtik I[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psammetichus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bust of Psamtik I, Metropolitan Museum of Art | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 664–610 BC (26th Dynasty) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Necho I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Necho II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Mehytenweskhet[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Necho II Nitocris I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Necho I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Queen Istemabet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 610 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Background

Historical references for what the Greeks referred to as the Dodecarchy, a loose confederation of twelve Egyptian territories, based on the traditional nomes, and the rise of Psamtik I in power, establishing the Saitic Dynasty, are recorded in Herodotus's Histories, Book II: 151–157. From cuneiform texts, it was discovered that twenty local princelings were appointed by Esarhaddon and confirmed by Ashurbanipal to govern Egypt.

Necho I, the father of Psamtik by his queen Istemabet, was the chief of these kinglets, but they seem to have been quite unable to lead the Egyptians under the hated Assyrians against the more sympathetic Nubians. The labyrinth built by Amenemhat III of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt is ascribed by Herodotus to the Dodecarchy, which must represent this combination of rulers.

Necho I died in 664 BC when the Kushite king Tantamani tried unsuccessfully to seize control of lower Egypt from the Assyrian Empire. After his father's death, within the first ten years of his reign, Psamtik both united all of Egypt and freed it from Assyrian control.

Military campaigns

Psamtik reunified Egypt in his ninth regnal year when he dispatched a powerful naval fleet in March 656 BC to Thebes and compelled the existing God's Wife of Amun at Thebes, Shepenupet II, daughter of the former Kushite Pharaoh Piye, to adopt his daughter Nitocris I as her heiress in the so-called Adoption Stela.

Psamtik's victory destroyed the last vestiges of the Nubian Twenty-fifth Dynasty's control over Upper Egypt under Tantamani since Thebes now accepted his authority. Nitocris would hold her office for 70 years from 656 BC until her death in 585 BC. Thereafter, Psamtik campaigned vigorously against those local princes who opposed his reunification of Egypt. One of his victories over certain Libyan marauders is mentioned in a Year 10 and Year 11 stela from the Dakhla Oasis.

Psamtik won Egypt's independence from the Assyrian Empire and restored Egypt's prosperity during his 54-year reign. The pharaoh proceeded to establish close relations with archaic Greece and also encouraged many Greek settlers to establish colonies in Egypt and serve in the Egyptian army. In particular, he settled some Greeks at Tahpanhes (Daphnae).[5]

Discovering the origin of language (Hypothesis)

The Greek historian Herodotus conveyed an anecdote about Psamtik in the second volume of his Histories (2.2). During his visit to Egypt, Herodotus heard that Psammetichus ("Psamṯik") sought to discover the origin of language by conducting an experiment with two children. Allegedly he gave two newborn babies to a shepherd, with the instructions that no one should speak to them, but that the shepherd should feed and care for them while listening to determine their first words. The hypothesis was that the first word would be uttered in the root language of all people. When one of the children cried "βεκός" (bekós) with outstretched arms, the shepherd reported this to Psammetichus, who concluded that the word was Phrygian because that was the sound of the Phrygian word for "bread". Thus, they concluded that the Phrygians were an older people than the Egyptians, and that Phrygian was the original language of men. There are no other extant sources to verify this story.[8]

Wives

Psamtik's chief wife was Mehytenweskhet, the daughter of Harsiese, the vizier of the North and High Priest of Atum at Heliopolis. Psamtik and Mehytenweskhet were the parents of Necho II, Merneith, and the Divine Adoratrice Nitocris I.

Psamtik's father-in-law—the aforementioned Harsiese—was married three times: to Sheta, with whom he had a daughter named Naneferheres, to Tanini and, finally, to an unknown woman, by whom he had both Djedkare, the vizier of the South and Mehytenweskhet.[9] Harsiese was the son of vizier Harkhebi, and was related to two other Harsieses, both viziers, who were a part of the family of the famous Mayor of Thebes Montuemhat.

Statue discovery

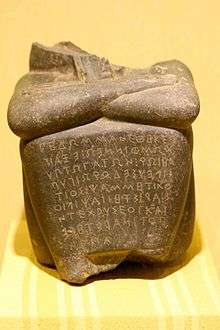

On 9 March 2017, Egyptian and German archaeologists discovered a colossal statue about 7.9 metres (26 ft) in height at the Heliopolis site in Cairo. Made of quartzite, the statue was found in a fragmentary state, with the bust, the lower part of the head and the crown submerged in groundwater.[10]

It has been confirmed to be of Psamtik I due to engravings found that mentioned one of the pharaoh's names on the base of the statue.[11][12][13][14][15]

A spokesperson at the time commented that "If it does belong to this king, then it is the largest statue of the Late Period that was ever discovered in Egypt."[16][17] The head and torso are expected to be moved to the Grand Egyptian Museum.[10]

The statue (colossus) was sculpted in the ancient classical style of 2000 BC, establishing a resurgence to the greatness and prosperity of the classical period of old. However, from the many gathered fragments (now 6,400 of them) of quartzite collected, it has also been established that the colossus was at some time deliberately destroyed. Certain discoloured & cracked rock fragments show evidence of having been heated to high temperatures then shattered (with cold water), a typical way of destroying ancient colossi.

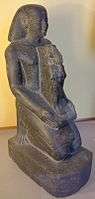

Psamtik I kneeling, Louvre Museum

Psamtik I kneeling, Louvre Museum Relief of Psamtik I making an offering to Ra-Horakhty (Tomb of Pabasa)

Relief of Psamtik I making an offering to Ra-Horakhty (Tomb of Pabasa)

References

- "Psamtek I Wahibre". Digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2 December 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Peter Clayton, Chronicle of the Pharaohs, Thames and Hudson, 1994. p.195

- Eichler, Ernst (1995). Namenforschung / Name Studies / Les noms propres. 1. Halbband. Walter de Gruyter. p. 847. ISBN 3110203421.

- "Psamtik I". Touregypt.net. Archived from the original on 22 November 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Smith, Tyler Jo; Plantzos, Dimitris (2018). A Companion to Greek Art. John Wiley & Sons. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-119-26681-5.

- Keesling, Catherine M. (2017). Early Greek Portraiture. Cambridge University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-107-16223-5.

- Smith, Tyler Jo; Plantzos, Dimitris (2018). A Companion to Greek Art. John Wiley & Sons. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-119-26681-5.

- Herodotus, "2.2.3", Histories, Internet Classics Archive, retrieved 18 March 2017.

- Nos ancêtres de l'Antiquité, 1991, Christian Settipani, pp. 153, 160 & 161

- "Massive Statue of Ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Found in City Slum". National Geographic. 10 March 2017. Archived from the original on 11 March 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- Youssef, Nour (17 March 2017). "So Many Pharaohs: A Possible Case of Mistaken Identity in Cairo". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- Thompson, Ben (18 March 2017). "Two pharaohs, one statue: A tale of mistaken identity?". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- "Egypt Pharaoh statue 'not Ramses II but different ruler'". BBC News. 16 March 2017. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- "Inscription reveals colossus unearthed in Cairo slum not of Ramses II, more likely Pharaoh Psamtek I". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 16 March 2017. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- Bel Trew (17 March 2017). "Statue found in Cairo may be biggest ever from the Late Period". The Times. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- "Egypt Pharaoh statue 'not Ramses II but different ruler". BBC News. 16 March 2017. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- Hendawi, Hamza. "Recently discovered Egyptian statue is not Ramses II". CTVNews. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

Bibliography

Further reading

- Dodson, Aidan (2012). Afterglow of Empire: Egypt from the Fall of the New Kingdom to the Saite Renaissance. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9774165314.

- Breasted, James Henry (1906). Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest. Ancient Records, Second Series. IV. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. LCCN 06005480.

- Morkot, Robert (2003). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Egyptian Warfare. Scarecrow Press. pp. 173–174. ISBN 0810848627.

- Spalinger, Anthony (1976). Psammetichus, King of Egypt: I. New York: Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. pp. 133–147. OCLC 83844336.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Psammetichus I. |

- "Psamtik I". Encyclopedia Britannica. 23 October 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- "Bust from Statue of a King". Met Museum. Retrieved 18 March 2017.