Osiris

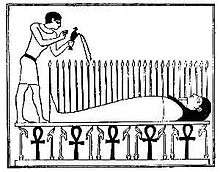

Osiris (/oʊˈsaɪrɪs/, from Egyptian wsjr, Coptic ⲟⲩⲥⲓⲣⲉ)[1][2] is the god of fertility, agriculture, the afterlife, the dead, resurrection, life, and vegetation in ancient Egyptian religion. He was classically depicted as a green-skinned deity with a pharaoh's beard, partially mummy-wrapped at the legs, wearing a distinctive atef crown, and holding a symbolic crook and flail.[3] He was one of the first to be associated with the mummy wrap. When his brother, Set, cut him up into pieces after killing him, Isis, his wife, found all the pieces and wrapped his body up. Osiris was at times considered the eldest son of the god Geb[4] and the sky goddess Nut, as well as being brother and husband of Isis, with Horus being considered his posthumously begotten son.[4] He was also associated with the epithet Khenti-Amentiu, meaning "Foremost of the Westerners", a reference to his kingship in the land of the dead.[5] Through syncretism with Iah, he is also a god of the Moon.[6]

| Osiris | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Osiris, lord of the dead and rebirth. His green skin symbolizes rebirth. | ||||

| Name in hieroglyphs | ||||

| Major cult center | Busiris, Abydos | |||

| Symbol | Crook and flail, Atef crown, ostrich feathers, fish, mummy gauze, djed | |||

| Personal information | ||||

| Parents | Geb and Nut | |||

| Siblings | Isis, Set, Nephthys, Heru Wer | |||

| Consort | Isis | |||

| Offspring | Horus, Anubis (in some accounts) | |||

Osiris can be considered the brother of Isis, Set, Nephthys, and Horus the Elder, and father of Horus the Younger.[7] The first evidence of the worship of Osiris was found in the middle of the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt (25th century BC), although it is likely that he was worshiped much earlier;[8] the Khenti-Amentiu epithet dates to at least the First Dynasty, and was also used as a pharaonic title. Most information available on the myths of Osiris is derived from allusions contained in the Pyramid Texts at the end of the Fifth Dynasty, later New Kingdom source documents such as the Shabaka Stone and the Contending of Horus and Seth, and much later, in narrative style from the writings of Greek authors including Plutarch[9] and Diodorus Siculus.[10]

Osiris was the judge of the dead and the underworld agency that granted all life, including sprouting vegetation and the fertile flooding of the Nile River. He was described as "He Who is Permanently Benign and Youthful"[11] and the "Lord of Silence".[12] The kings of Egypt were associated with Osiris in death – as Osiris rose from the dead so they would be in union with him, and inherit eternal life through a process of imitative magic.[13]

Through the hope of new life after death, Osiris began to be associated with the cycles observed in nature, in particular vegetation and the annual flooding of the Nile, through his links with the heliacal rising of Orion and Sirius at the start of the new year.[11] Osiris was widely worshipped until the decline of ancient Egyptian religion during the rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire.[14][15]

Etymology of the name

Osiris is a Latin transliteration of the Ancient Greek Ὄσιρις IPA: [ó.siː.ris], which in turn is the Greek adaptation of the original name in the Egyptian language. In Egyptian hieroglyphs the name appears as wsjr, which some Egyptologists instead choose to transliterate ꜣsjr or jsjrj. Since hieroglyphic writing lacks vowels, Egyptologists have vocalized the name in various ways, such as Asar, Ausar, Ausir, Wesir, Usir, or Usire.

Several proposals have been made for the etymology and meaning of the original name; as Egyptologist Mark J. Smith notes, none are fully convincing.[16] Most take wsjr as the accepted transliteration, following Adolf Erman:

- John Gwyn Griffiths (1980), "bearing in mind Erman's emphasis on the fact that the name must begin with an [sic] w", proposes a derivation from wsr with an original meaning of "The Mighty One".[17]

- Kurt Sethe (1930) proposes a compound st-jrt, meaning "seat of the eye", in a hypothetical earlier form *wst-jrt; this is rejected by Griffiths on phonetic grounds.[17]

- David Lorton (1985) takes up this same compound but explains st-jrt as signifying "product, something made", Osiris representing the product of the ritual mummification process.[16]

- Wolfhart Westendorf (1987) proposes an etymology from wꜣst-jrt "she who bears the eye".[18][19]

- Mark J. Smith (2017) makes no definitive proposals but asserts that the second element must be a form of jrj ("to do, make") (rather than jrt ("eye")).[16]

However, recently alternative transliterations have been proposed:

- Yoshi Muchiki (1990) reexamines Erman's evidence that the throne hieroglyph in the word is to be read ws and finds it unconvincing, suggesting instead that the name should be read ꜣsjr on the basis of Aramaic, Phoenician, and Old South Arabian transcriptions, readings of the throne sign in other words, and comparison with ꜣst ("Isis").[20]

- James P. Allen (2000) reads the word as jsjrt [21] but revises the reading (2013) to jsjrj and derives it from js-jrj, meaning "engendering (male) principle".[22]

Appearance

Osiris is represented in his most developed form of iconography wearing the Atef crown, which is similar to the White crown of Upper Egypt, but with the addition of two curling ostrich feathers at each side. He also carries the crook and flail. The crook is thought to represent Osiris as a shepherd god. The symbolism of the flail is more uncertain with shepherds whip, fly-whisk, or association with the god Andjety of the ninth nome of Lower Egypt proposed.[11]

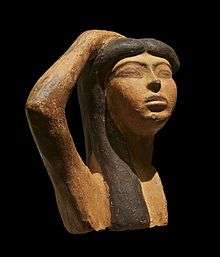

He was commonly depicted as a pharaoh with a complexion of either green (the color of rebirth) or black (alluding to the fertility of the Nile floodplain) in mummiform (wearing the trappings of mummification from chest downward).[23]

Early mythology

The Pyramid Texts describe early conceptions of an afterlife in terms of eternal travelling with the sun god amongst the stars. Amongst these mortuary texts, at the beginning of the Fourth Dynasty, is found: "An offering the king gives and Anubis". By the end of the Fifth Dynasty, the formula in all tombs becomes "An offering the king gives and Osiris".[24]

Father of Horus

Osiris is the mythological father of the god Horus, whose conception is described in the Osiris myth (a central myth in ancient Egyptian belief). The myth describes Osiris as having been killed by his brother, Set, who wanted Osiris' throne. His wife, Isis finds the body of Osiris and hides it in the reeds where it is found and dismembered by Set. Isis retrieves and joins the fragmented pieces of Osiris, then briefly revives Osiris by use of magic. This spell gives her time to become pregnant by Osiris. Isis later gives birth to Horus. As such, since Horus was born after Osiris' resurrection, Horus became thought of as a representation of new beginnings and the vanquisher of the usurper Set.

Ptah-Seker (who resulted from the identification of Creator god Ptah with Seker) thus gradually became identified with Osiris, the two becoming Ptah-Seker-Osiris. As the sun was thought to spend the night in the underworld, and was subsequently "reborn" every morning, Ptah-Seker-Osiris was identified as king of the underworld, god of the afterlife, life, death, and regeneration.

Ram god

| Banebdjed (b3-nb-ḏd) in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Osiris' soul, or rather his Ba, was occasionally worshipped in its own right, almost as if it were a distinct god, especially in the Delta city of Mendes. This aspect of Osiris was referred to as Banebdjedet, which is grammatically feminine (also spelt "Banebded" or "Banebdjed"), literally "the ba of the lord of the djed, which roughly means The soul of the lord of the pillar of continuity. The djed, a type of pillar, was usually understood as the backbone of Osiris.

The Nile supplying water, and Osiris (strongly connected to the vegetable regeneration) who died only to be resurrected, represented continuity and stability. As Banebdjed, Osiris was given epithets such as Lord of the Sky and Life of the (sun god) Ra. Ba does not mean "soul" in the western sense, and has to do with power, reputation, force of character, especially in the case of a god.

Since the ba was associated with power, and also happened to be a word for ram in Egyptian, Banebdjed was depicted as a ram, or as Ram-headed. A living, sacred ram was kept at Mendes and worshipped as the incarnation of the god, and upon death, the rams were mummified and buried in a ram-specific necropolis. Banebdjed was consequently said to be Horus' father, as Banebdjed was an aspect of Osiris.

Regarding the association of Osiris with the ram, the god's traditional crook and flail are the instruments of the shepherd, which has suggested to some scholars also an origin for Osiris in herding tribes of the upper Nile.

Mythology

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

Beliefs |

|

Practices

|

|

Deities (list) |

|

Locations |

|

Symbols and objects

|

|

Related religions

|

|

|

Plutarch recounts one version of the Osiris myth in which Set (Osiris' brother), along with the Queen of Ethiopia, conspired with 72 accomplices to plot the assassination of Osiris.[25] Set fooled Osiris into getting into a box, which Set then shut, sealed with lead, and threw into the Nile. Osiris' wife, Isis, searched for his remains until she finally found him embedded in a tamarisk tree trunk, which was holding up the roof of a palace in Byblos on the Phoenician coast. She managed to remove the coffin and retrieve her husband's body.

In one version of the myth, Isis used a spell to briefly revive Osiris so he could impregnate her. After embalming and burying Osiris, Isis conceived and gave birth to their son, Horus. Thereafter Osiris lived on as the god of the underworld. Because of his death and resurrection, Osiris was associated with the flooding and retreating of the Nile and thus with the yearly growth and death of crops along the Nile valley.

Diodorus Siculus gives another version of the myth in which Osiris was described as an ancient king who taught the Egyptians the arts of civilization, including agriculture, then travelled the world with his sister Isis, the satyrs, and the nine muses, before finally returning to Egypt. Osiris was then murdered by his evil brother Typhon, who was identified with Set. Typhon divided the body into twenty-six pieces, which he distributed amongst his fellow conspirators in order to implicate them in the murder. Isis and Hercules (Horus) avenged the death of Osiris and slew Typhon. Isis recovered all the parts of Osiris' body, except the phallus, and secretly buried them. She made replicas of them and distributed them to several locations, which then became centres of Osiris worship.[26][27]

Worship

Annual ceremonies were performed in honor of Osiris in various places across Egypt.[28] These ceremonies were fertility rites which symbolised the resurrection of Osiris.[29] Recent scholars emphasize "the androgynous character of [Osiris'] fertility" clear from surviving material. For instance, Osiris' fertility has to come both from being castrated/cut-into-pieces and the reassembly by female Isis, whose embrace of her reassembled Osiris produces the perfect king, Horus.[30] Further, as attested by tomb-inscriptions, both women and men could syncretize (identify) with Osiris at their death, another set of evidence that underline Osiris' androgynous nature.[31]

Death or transition and institution as god of the afterlife

Plutarch and others have noted that the sacrifices to Osiris were "gloomy, solemn, and mournful..." (Isis and Osiris, 69) and that the great mystery festival, celebrated in two phases, began at Abydos commemorating the death of the god, on the same day that grain was planted in the ground (Isis and Osiris, 13). The annual festival involved the construction of "Osiris Beds" formed in shape of Osiris, filled with soil and sown with seed.[34]

The germinating seed symbolized Osiris rising from the dead. An almost pristine example was found in the tomb of Tutankhamun by Howard Carter.[35] Associated with the grain god Nepri (Neper).

The first phase of the festival was a public drama depicting the murder and dismemberment of Osiris, the search of his body by Isis, his triumphal return as the resurrected god, and the battle in which Horus defeated Set.

According to Julius Firmicus Maternus of the fourth century, this play was re-enacted each year by worshippers who "beat their breasts and gashed their shoulders.... When they pretend that the mutilated remains of the god have been found and rejoined...they turn from mourning to rejoicing." (De Errore Profanorum).

The passion of Osiris was reflected in his name 'Wenennefer" ("the one who continues to be perfect"), which also alludes to his post mortem power.[23]

Ikhernofret Stela

Much of the extant information about the rites of Osiris can be found on the Ikhernofret Stela at Abydos erected in the Twelfth Dynasty by Ikhernofret, possibly a priest of Osiris or other official (the titles of Ikhernofret are described in his stela from Abydos) during the reign of Senwosret III (Pharaoh Sesostris, about 1875 BC). The ritual reenactment of Osiris's funeral rites were held in the last month of the inundation (the annual Nile flood), coinciding with Spring, and held at Abydos which was the traditional place where the body of Osiris drifted ashore after having been drowned in the Nile.[36]

The part of the myth recounting the chopping up of the body into 14 pieces by Set is not recounted in this particular stela. Although it is attested to be a part of the rituals by a version of the Papyrus Jumilhac, in which it took Isis 12 days to reassemble the pieces, coinciding with the festival of ploughing.[37] Some elements of the ceremony were held in the temple, while others involved public participation in a form of theatre. The Stela of Ikhernofret recounts the programme of events of the public elements over the five days of the Festival:

- The First Day, The Procession of Wepwawet: A mock battle was enacted during which the enemies of Osiris are defeated. A procession was led by the god Wepwawet ("opener of the way").

- The Second Day, The Great Procession of Osiris: The body of Osiris was taken from his temple to his tomb. The boat he was transported in, the "Neshmet" bark, had to be defended against his enemies.

- The Third Day: Osiris is Mourned and the Enemies of the Land are Destroyed.

- The Fourth Day, Night Vigil: Prayers and recitations are made and funeral rites performed.

- The Fifth Day, Osiris is Reborn: Osiris is reborn at dawn and crowned with the crown of Ma'at. A statue of Osiris is brought to the temple.[36]

Wheat and clay rituals

Contrasting with the public "theatrical" ceremonies sourced from the I-Kher-Nefert stele (from the Middle Kingdom), more esoteric ceremonies were performed inside the temples by priests witnessed only by chosen initiates. Plutarch mentions that (for much later period) two days after the beginning of the festival "the priests bring forth a sacred chest containing a small golden coffer, into which they pour some potable water...and a great shout arises from the company for joy that Osiris is found (or resurrected). Then they knead some fertile soil with the water...and fashion therefrom a crescent-shaped figure, which they cloth and adorn, this indicating that they regard these gods as the substance of Earth and Water." (Isis and Osiris, 39). Yet his accounts were still obscure, for he also wrote, "I pass over the cutting of the wood" – opting not to describe it, since he considered it as a most sacred ritual (Ibid. 21).

In the Osirian temple at Denderah, an inscription (translated by Budge, Chapter XV, Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection) describes in detail the making of wheat paste models of each dismembered piece of Osiris to be sent out to the town where each piece is discovered by Isis. At the temple of Mendes, figures of Osiris were made from wheat and paste placed in a trough on the day of the murder, then water was added for several days, until finally the mixture was kneaded into a mold of Osiris and taken to the temple to be buried (the sacred grain for these cakes were grown only in the temple fields). Molds were made from the wood of a red tree in the forms of the sixteen dismembered parts of Osiris, the cakes of "divine" bread were made from each mold, placed in a silver chest and set near the head of the god with the inward parts of Osiris as described in the Book of the Dead (XVII).

Judgement

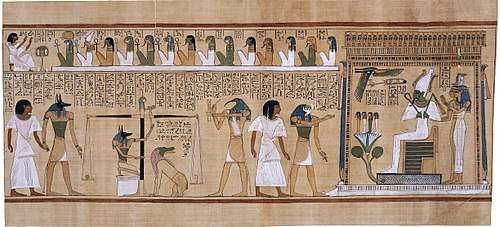

The idea of divine justice being exercised after death for wrongdoing during life is first encountered during the Old Kingdom in a Sixth Dynasty tomb containing fragments of what would be described later as the Negative Confessions performed in front of the 42 Assessors of Ma'at.[38]

At death a person faced judgment by a tribunal of forty-two divine judges. If they led a life in conformance with the precepts of the goddess Ma'at, who represented truth and right living, the person was welcomed into the kingdom of Osiris. If found guilty, the person was thrown to the soul-eating demon Ammit and did not share in eternal life.[39] The person who is taken by the devourer is subject first to terrifying punishment and then annihilated. These depictions of punishment may have influenced medieval perceptions of the inferno in hell via early Christian and Coptic texts.[40] Purification for those who are considered justified may be found in the descriptions of "Flame Island", where they experience the triumph over evil and rebirth. For the damned, complete destruction into a state of non-being awaits, but there is no suggestion of eternal torture.[41][42]

During the reign of Seti I, Osiris was also invoked in royal decrees to pursue the living when wrongdoing was observed but kept secret and not reported.[43]

Greco-Roman era

Hellenization

The early Ptolemaic kings promoted a new god, Serapis, who combined traits of Osiris with those of various Greek gods and was portrayed in a Hellenistic form. Serapis was often treated as the consort of Isis and became the patron deity of the Ptolemies' capital, Alexandria.[44] Serapis's origins are not known. Some ancient authors claim the cult of Serapis was established at Alexandria by Alexander the Great himself, but most who discuss the subject of Serapis's origins give a story similar to that by Plutarch. Writing about 400 years after the fact, Plutarch claimed that Ptolemy I established the cult after dreaming of a colossal statue at Sinope in Anatolia. His councillors identified as a statue of the Greek god Pluto and said that the Egyptian name for Pluto was Serapis. This name may have been a Hellenization of "Osiris-Apis".[45] Osiris-Apis was a patron deity of the Memphite Necropolis and the father of the Apis bull who was worshipped there, and texts from Ptolemaic times treat "Serapis" as the Greek translation of "Osiris-Apis". But little of the early evidence for Serapis's cult comes from Memphis, and much of it comes from the Mediterranean world with no reference to an Egyptian origin for Serapis, so Mark Smith expresses doubt that Serapis originated as a Greek form of Osiris-Apis's name and leaves open the possibility that Serapis originated outside Egypt.[46]

In popular culture

See also

- Aaru

- Ancient Egyptian concept of the soul

Notes

- "Coptic Dictionary Online". corpling.uis.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- Allen, James P. (2010). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139486354.

- "Egyptian Mythology - Osiris Cult". www.touregypt.net (in Russian). Retrieved 2018-10-26.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-500-05120-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collier, Mark; Manley, Bill (1998). How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs, British Museum Press, p. 41, ISBN 0-7141-1910-5

- Quirke, S.; Spencer, A. J. (1992). The British Museum Book of Ancient Egypt. London: The British Museum Press.

- Kane Chronicles

- Griffiths, John Gwyn (1980). The Origins of Osiris and His Cult. Brill. p. 44

- "Isis and Osiris", Plutarch, translated by Frank Cole Babbitt, 1936, vol. 5 Loeb Classical Library. Penelope.uchicago.edu

- "The Historical Library of Diodorus Siculus", vol. 1, translated by G. Booth, 1814.

- The Oxford Guide: Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology, Edited by Donald B. Redford, pp. 302–307, Berkley, 2003, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

- "The Burden of Egypt", J. A. Wilson, p. 302, University of Chicago Press, 4th imp 1963

- "Man, Myth and Magic", Osiris, vol. 5, pp. 2087–2088, S.G.F. Brandon, BPC Publishing, 1971.

- "Catholic Encyclopedia: Theodosius I". Newadvent.org. 1912-07-01. Retrieved 2012-05-01.

- "History of the Later Roman Empire from the Death of Theodosius I. to the Death of Justinian", The Suppression of Paganism – ch22, p. 371, John Bagnell Bury, Courier Dover Publications, 1958, ISBN 0-486-20399-9

- Smith, Mark (2017). Following Osiris: Perspectives on the Osirian Afterlife from Four Millennia. pp. 124–125.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Griffiths, John Gwyn (1980/2018). The Origins of Osiris and His Cult. pp. 89–95. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - (Mathieu 2010, p. 79) : Mais qui est donc Osiris ? Ou la politique sous le linceul de la religion

- Westendorf, Wolfhart (1987). "Zur Etymologie des Namens Osiris: *wꜣs.t-jr.t "die das Auge trägt"". Form und Mass: Beiträge zur Literatur, Sprache und Kunst des Alten Ägypten: Festschrift für Gerhard Fecht zum 65. Geburtstag Am 6. Februar 1987 (in German): 456–461.

- Muchiki, Yoshi (1990). "On the transliteration of the name Osiris". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 76: 191–194. doi:10.1177/030751339007600127.

- Allen, James P. (2010-04-15). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139486354.

- Allen, James P. (2013). "The Name of Osiris (and Isis)". Lingua Aegyptia. 21: 9–14.

- "How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs", Mark Collier & Bill Manley, British Museum Press, p. 42, 1998, ISBN 0-7141-1910-5

- "Architecture of the Afterlife: Understanding Egypt's pyramid tombs", Ann Macy Roth, Archaeology Odyssey, Spring 1998

- Plutarch's Moralia, On Isis and Osiris, ch. 12. 1874. Retrieved 2012-05-01.

- "Osiris", Man, Myth & Magic, S.G.F Brandon, Vol5 P2088, BPC Publishing.

- "The Historical Library of Diodorus Siculus", translated by George Booth 1814. retrieved 3 June 2007. Google Books

- Racheli Shalomi-Hen, The Writing of Gods: the Evolution of Divine Classifiers in the Old Kingdom (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2006), 69-95.

- Early 20th-century scholar E.A. Wallis Budge (over) emphasizes Osiris' action: "Osiris is closely connected with the germination of wheat; the grain which is put into the ground is the dead Osiris, and the grain which has germinated is the Osiris who has once again renewed his life." E.A. Wallis Budge, Osiris and the Egyptian resurrection, Volume 2 (London: P. L. Warner; New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1911), 32.

- Ann M. Roth, “Father Earth, Mother Sky: Ancient Egyptian Beliefs about Conception and Fertility,” in Reading the Body: Representations and Remains in the Archaeological Record, ed. Alison E. Rautman (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), 187-201.

- Roth, 199.

- "Egyptian ideas of the future life.", E. A Wallis Budge, chapter 1, E. A Wallis Budge, org pub 1900

- "Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses", George Hart, p119, Routledge, 2005 ISBN 0-415-34495-6

- Teeter, Emily (2011). Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge University Press. pp. 58–66

- "Osiris Bed, Burton photograph p2024, The Griffith Institute".

- "The passion plays of osiris". ancientworlds.net. Archived from the original on 2007-06-26.

- J. Vandier, "Le Papyrus Jumilhac", pp. 136–137, Paris, 1961

- "Studies in Comparative Religion", General editor, E. C Messenger, Essay by A. Mallon S. J, vol 2/5, p. 23, Catholic Truth Society, 1934

- Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt, Rosalie David, pp. 158–159, Penguin, 2002, ISBN 0-14-026252-0

- "The Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology: The Oxford Guide", "Hell", pp. 161–162, Jacobus Van Dijk, Berkley Reference, 2003, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

- "The Divine Verdict", John Gwyn Griffiths, p. 233, Brill Publications, 1991, ISBN 90-04-09231-5

- "Letter: Hell in the ancient world. Letter by Professor J. Gwyn Griffiths". The Independent. December 31, 1993.

- "The Burden of Egypt", J.A Wilson, p. 243, University of Chicago Press, 4th imp 1963; The INSCRIPTIONS OF REDESIYEH from the reign of Seti I include "As for anyone who shall avert the face from the command of Osiris, Osiris shall pursue him, Isis shall pursue his wife, Horus shall pursue his children, among all the princes of the necropolis, and they shall execute their judgment with him." (Breasted Ancient Egyptian Records, Vol 3, p. 86)

- Wilkinson (2003), pp. 127–128.

- Françoise Dunand and Christiane Zivie-Coche (2004), Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE, pp. 214–215

- Smith (2017), pp. 390–394.

- Dijkstra, Jitse H. F. (2008). Philae and the End of Egyptian Religion, pp. 337–348

External links

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article "Osiris". |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Osiris. |

- Osiris—"Ancient Egypt on a Comparative Method"

- Osiris Egyptian God of the Underworld