21st Century Maritime Silk Road

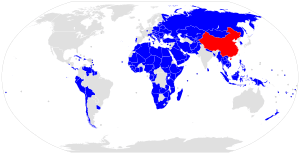

The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (Chinese: 21世纪海上丝绸之路), commonly just Maritime Silk Road (MSR), is the sea route part of the Belt and Road Initiative which is[1] a Chinese strategic initiative to increase investment and foster collaboration across the historic Silk Road.[2][3][4] The project builds on the maritime expedition routes of Admiral Zheng He.

The maritime silk road essentially runs from the Chinese coast to the south via Hanoi to Jakarta, Singapore and Kuala Lumpur through the Strait of Malacca via the Sri Lankan Colombo towards the southern tip of India via Malé, to the East African Mombasa, from there to Djibouti, then through the Red Sea via the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean, there via Haifa, Istanbul and Athens to the Upper Adriatic region to the northern Italian hub of Trieste with its international free port and its rail connections to Central Europe and the North Sea.

The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor is an extension to the proposed Silk Road. The Maritime Silk Road coincides with the theory of China's String of Pearls strategy.

History

The Maritime Silk Road initiative was first proposed by Chinese leader Xi Jinping during a speech to the Indonesian Parliament in October 2013.[5]

In November 2014, Chinese leader Xi Jinping announced plans to create a USD $40B development fund, which would help finance China's plans to develop the New Silk Road and the Maritime Silk Road. China has accelerated its drive to draw Africa into the MSR by speedy construction of a modern standard-gauge rail link between Nairobi and Mombasa.[6]

In March 2015, the National Development and Reform Commission of the People's Republic of China publicly released a document titled Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road,[7] which discusses the principles and framework which form the foundation of the initiative.

Routes and Key Ports

Although the routes encompassed in the MSR will be copious if the initiative comes to fruition, to date there has not been ample official information released concerning specific ports.

Between 2015 and 2017, China has leased ownership over the following ports:[8]

- Gwadar, Pakistan: 40 years

- Kyaukpyu, Myanmar: 50 years

- Kuantan, Malaysia: 60 years

- Obock, Djibouti: 10 years

- Malacca Gateway: 99 Years

- Hambantota, Sri Lanka: 99 years

- Muara, Brunei: 60 years

- Feydhoo Finolhu, Maldives: 50 years

In the 2018 Xinhua-Baltic International Shipping Centre Development Index Report,[9] the China Economic Information Service cites the following as major routes for the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road:

China - Southeast Asia Route

China-Vietnam, Myanmar

Qinzhou - Yangpu - Zhanjiang - Gaolan Port - Yantian - Nansha - Ho Chi Minh City (Vietnam) - Singapore - Yangon (Myanmar) - Palawan (Philippines) - Singapore - Qinzhou.

Singapore, Malaysia

Newport - Dalian - Qingdao - Shanghai - Xiamen - Hong Kong - Singapore - Klang Port (Malaysia) - Penang (Malaysia) - Singapore - Hong Kong - Xingang.

Indonesia

Shanghai - Newport - Dalian - Qingdao - Ningbo - Nansha - Jakarta (Indonesia) - Klang Port (Malaysia) - Singapore - Laem Chabang Port (Thailand) - Hong Kong - Shanghai.

China-Thailand, Cambodia

Ningbo - Shanghai - Shekou - Sihanoukville (Cambodia) - Bangkok - Leam Chabang (Thailand) - Ningbo.

China - South Asia Route

China-Pakistan

Qingdao - Shanghai - Ningbo - Singapore - Klang Port (Malaysia) - Karachi (Pakistan) - Mundra (India) - Colombo (Sri Lanka) - Singapore - Qingdao.

India, Sri Lanka

Shanghai - Ningbo - Shekou - Singapore - Port Klang (Malaysia) - Nawa Shiva (India) - Pipavav (India) - Colombo (Sri Lanka) - Port Klang - Singapore - Ho Chi Minh City (Vietnam) - Hong Kong - Shanghai.

Middle East, East Africa Route

China-Iraq, UAE

Shanghai - Ningbo - Kaohsiung - Xiamen - Shekou - Port Klang (Malaysia) - Alishan Port (UAE) - Umm Qasr (Iraq) - Port Klang - Kaohsiung - Shanghai.

China-Red Sea

Shanghai - Ningbo - Xiamen - Chiwan - Singapore - Djibouti (East Africa) - Jeddah (Saudi Arabia) - Sudan (Sudan) - Djibouti - Port Klang - Shanghai.

Europe Route

The MSR route to Europe will begin in China, pass through the Malacca Strait, follow Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea, and visit ports in Greece, Italy, France, and Spain before returning to China. Of particular interest to China is the port of Piraeus in Athens, Greece, which Chinese Premier Li Keqiang stated "...can become China's gateway to Europe. It is the pearl of the Mediterranean."[10]

Qingdao — Shanghai — Ningbo — Kaohsiung — Hong Kong —Yantian — Singapore — Piraeus ( Greece) — Trieste — La Spezia (Italy) —Genoa (Italy)—Fos-sur-Mer (France) —Valencia (Spain)— Piraeus (Greece)—Jeddah (Saudi Arabia)— Colombo (Sri Lanka)— Singapore — Hong Kong

Challenges

There exists a number of unresolved territorial disputes in the South China Sea between China and ASEAN countries such as Brunei, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam.[8] Potential routes proposed for the MSR could contribute to increasing tensions over certain areas. However, some academics propose that the MSR initiative will provide a means for China to resolve these sovereignty-related conflicts by providing an opportunity for mutual gain.[11]

It has been suggested that the future of the MSR will be largely dictated by the economic conditions of the participating countries.[12] The possibility exists that China may have to make financial contributions to other MSR countries who are experiencing poor economic conditions. China will need to ensure that any loans allocated to these countries are spent appropriately.[13]

Coordination on the national and subnational levels may be challenging for China. It has been stated that China's subnational actors - such as multinational corporations, provinces, cities, and towns - have a tendency to strongly prioritize their own interests above those of the nation and participate in government initiatives primarily to satisfy their own objectives. This could lead to inappropriate spending on projects outside the scope of China's national interests.[14]

Gaining political approval from countries with different political systems could prove problematic for China. Countries may be weary about joining the MSR initiative due to geopolitical and security factors.[15]

Concerns have been put forth regarding whether China will be able to receive India's cooperation and participating in bringing the initiative to fruition.[16][17][12] India represents a strong economic force and may likely prefer to develop the Indian Ocean region's infrastructure itself rather than allow China to have any control over the region.[16] While Chinese investment in India's underdeveloped maritime infrastructure could benefit India's economy greatly, India remains wary to accept such investment as the possibility exists that China is primarily attempting to expand its own territorial and economic interests.[18] India has also expressed circumspection in participating in a similar initiative, the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar economic corridor.[12]

References

- Kuo, Lily; Kommenda, Niko. "What is China's Belt and Road Initiative?". the Guardian. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- "Sri Lanka Supports China's Initiative of a 21st Century Maritime Silk Route". 2015-05-11. Archived from the original on 2015-05-11. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- Diplomat, Shannon Tiezzi, The. "China Pushes 'Maritime Silk Road' in South, Southeast Asia". The Diplomat. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- "Reflections on Maritime Partnership: Building the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road_China Institute of International Studies". www.ciis.org.cn. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- "Full text of President Xi's speech at opening of Belt and Road forum". www.fmprc.gov.cn. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- Page, Jeremy (2014-11-08). "China to Contribute $40 Billion to Silk Road Fund". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- "Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road". National Development and Reform Commission (NRDC) People's Republic of China. 28 March 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- "THE 21ST CENTURY MARITIME SILK ROAD: Security implications and ways forward for the European Union" (PDF). sipri.org. 30 March 2019.

- "Xinhua-Baltic 2018 International Shipping Centre Development Index Report" (PDF). safety4sea.com. 29 March 2019.

- Chazizam, M. (2018). The Chinese Maritime Silk Road Initiative: The Role of the Mediterranean. Mediterranean Quarterly, 29(2), 54-69.

- Hui-yi, Katherine Tseng (2016-06-16). "Re-contemplating the South China Sea Issue: Sailing with the Wind of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road". The Chinese Journal of Global Governance. 2 (1): 63–95. doi:10.1163/23525207-12340016. ISSN 2352-5207.

- Blanchard, J.-M. F. (2017). Probing China’s Twenty-First-Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative (MSRI): An Examination of MSRI Narratives. Geopolitics, 22(2), 246–268. doi:10.1080/14650045.2016.1267147

- Ibid.

- Ibid

- Ibid.

- Knowledge, CKGSB. "Mapping China's New Silk Road Initiative". Forbes. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- J. Yang, ‘Making the Maritime Silk Road a New Promoter of Cooperative Interaction between China and South Asia’, Keynote Speech given at the “Political Economy of China’s Maritime Silk Road and South Asia” conference, 21 Nov. 2015, Shanghai, China.

- Palit, Amitendu (2017-04-03). "India's Economic and Strategic Perceptions of China's Maritime Silk Road Initiative". Geopolitics. 22 (2): 292–309. doi:10.1080/14650045.2016.1274305. ISSN 1465-0045.

.svg.png)