History of Sino-Korean relations

The history of Sino-Korean relations dates back to prehistoric times.

Han and Gojoseon

According to Samguk Yusa, Wanggeom Joseon (Dangun Joseon) was the first country that represented Korean cultural identity.[1] Although controversial, a legend tells that around 1100 BC a sage named Gija and his intellectuals fled from Shang Dynasty to avoid political turmoil and sought asylum in Gojoseon, and active cultural trades ensued after. In 194 BC, Wiman, a general from Yan State, sought refugee along with Yan immigrants in Gojoseon, and he was given a duty to guard borders in Liaodong. Wiman eventually became a leader of new immigrants and indigenous population, which led him to usurp the throne of King Jun.[2] The expanding military might of Wiman Joseon soon threatened Han China, and the diplomatic relationship between the two countries deteriorated quickly. The Gojoseon–Han War occurred in 109 BC, resulting in the defeat of Gojoseon and the establishment of the Four Commanderies of Han. Chinese control over its northeast frontier and northern Korea provoked unity among the local tribes and indigenous population, resulting in the establishment of Goguryeo of Korea, which took advantage of Chinese conflict with the Xiongnu to expand into the Liaodong Peninsula.[3] Goguryeo eventually reconquered the former territories of Gojoseon and kept expanding in all directions.

Cao Wei and Goguryeo

In 238, Sima Yi of Cao Wei led a successful campaign against his rival Gongsun Yuan, with the aid of Goguryeo. This led to the Chinese recapture of Liaodong as well as establishing great contacts with the Korean kingdoms. By 242, the alliance between Cao Wei and Goguryeo broke down when Dongcheon of Goguryeo initiated a raid into Wei territory. In response, the Goguryeo–Wei War erupted in 244, ending with the sacking of the Goguryeo capital and resettlement of many of its inhabitants. 15 years later Goguryeo defeated Wei at Yangmaenggok.[4]

The Xianbei-ruled Former Yan dynasty sacked the Goguryeo capital and made the king pay tribute. However, Goguryeo triumphed over the Xianbei decades later when Gwanggaeto the Great defeated Later Yan and conquered Liaodong and most of Manchuria.[3]

Sui, Tang, Goguryeo, Balhae

Sui Dynasty launched four unsuccessful campaigns to subdue Goguryeo. Emperor Yang of Sui wanted to set order in East Asia after unifying various states and kingdoms within China proper. Goguryeo opposed this and started to prepare for defense against Sui Dynasty.[5] A series of invasions from Sui took place in year 598, 612, 613, and 614. In the Battle of Salsu River, Goguryeo general Eulji Mundeok and his army inflicted tremendous damage on the army of Sui, where only 2,700 survived out of 300,000 men.[6] Sui, out of exhaustion, disintegrated soon after.[6]

Goguryeo also engaged in many wars with Tang Dynasty of China, but it eventually lost as Silla, another Korean kingdom, took side with Tang instead in Goguryeo - Tang War. Later, Tang China rather saw the kingdom of Balhae, a successor state to Goguryeo, as a tributary state, whereas Balhae strongly opposed such view. As the Emperor of China saw himself as the emperor of the entire civilized world, it was not possible for such an emperor to have equal diplomatic relations with any other regional powers, and as such all diplomatic relations in the region were construed by the Chinese as tributary regardless of the intention of those regions.

Liao, Jin and Goryeo

During this time North China was ruled by the Khitan-ruled Liao Dynasty followed by the Jurchen-ruled Jin Dynasty. Goryeo triumphed over the Liao Dynasty in early 11th century and stalemated the Jin Dynasty in early 12th century. Goryeo paid tribute to maintain friendly relations and trade.

Mongol invasions

During the 13th century, the Mongol Empire invaded China and defeated the Jin and Song dynasties, eventually establishing the Yuan dynasty in 1271 under Kublai Khan. During the period of 1231–1259, the Mongol led Yuan Dynasty invaded Korea, ultimately resulting in the capitulation of Goryeo and becoming a tributary state of the Yuan Dynasty for 86 years until achieving its independence in 1356. The Yuan Dynasty eventually fell in 1368 and King Gongmin of Goryeo expanded its northern territory.

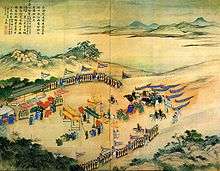

Ming and Joseon

Ming dynasty China shared a close trade and diplomatic relationship with Joseon Dynasty Korea. Both dynasties emerged from Mongol rule and shared Confucian ideals in society.

Ming China assisted Joseon Korea during Toyotomi Hideyoshi's invasion of Korea, in which the Wanli Emperor sent a total of 221,500 troops.

Qing and Joseon, and Korean Empire

Under Emperor Hong Taiji, the Manchuria-based Qing dynasty invaded Korea twice, in 1627 and 1636. Following the Second Manchu invasion of Korea, the Qing claimed victory and forced Injo of Joseon into submission, severing its relations with the collapsing Ming dynasty, which eventually fell in 1644. Qing China's national strength gradually declined after its defeat in the First and Second Opium Wars. As such, China was forced to sign a series of concessions and "unequal treaties" with the Western colonial powers. At the same time, the Meiji Restoration occurred in Japan and led to the rise of the Empire of Japan, which gradually expanded its military power. The Donghak Peasant Revolution of Korea in 1894 became a catalyst for the First Sino-Japanese War, which saw the defeat of the Qing military. As part of the terms in the post-war Treaty of Shimonoseki, China recognized the independence of Korea and ceased its tributary relations as well as Japan annexing the island of Taiwan (Formosa). The Korean Empire established modern diplomatic relationship with Qing, but Korea was eventually annexed, against their will, by Japan under the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910.

Republic of China and Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea

The anti-Japanese March 1st Movement protests erupted in Korea in 1919. Shortly after, the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea was established as a government in exile, based in Shanghai, with Syngman Rhee serving as its first president with its subsequent recognition by the Republic of China. They coordinated the armed resistance against the Japanese imperial army during the 1920s and 1930s, including the Battle of Qingshanli in October 1920 and Yoon Bong-Gil's assassination of Japanese officers in Shanghai in April 1932. The Provisional Government received modest recognition by the Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang regime in China.

Following the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the fall of Shanghai, the Korean Provisional Government relocated to Chongqing, where it formed the Korean Liberation Army (KLA) in 1941. The hundreds-strong KLA engaged in guerrilla warfare actions against the Japanese throughout the Asian theater of war until Japanese surrender in 1945.

The Republic of China was one of the participants of the Cairo Conference, which resulted in the Cairo Declaration. One of the main purposes of the Cairo Declaration was to create an independent Korea, free from Japanese Colonial Rule and restoration of Formosa and Manchuria to China.

Cultural relations

The Chinese character system, known as Hanja in Korean, was introduced into Korea through the spread of Buddhism during the Tang Dynasty. Hanja was used as the sole means of writing Korean until Sejong the Great promoted the invention of Hangul during the 15th century.

Confucianism also became a fundamental part of Korean society, rising into prominence under Goryeo and prospered under the Joseon Dynasty. Examples included civil service examinations, known as gwageo, and educational institutions (gukjagam and sungkyunkwan), promoting the studies of Chinese classical texts.

Since the nine years of Emperor Guangzong (958)of Song, he has followed the imperial examination system of the Tang Dynasty in China and established his own imperial examination system. Shuangji was a Chinese scholar. Emperor Guangzong appreciate his talent and admired the regular verse and rhythm in Tang verse, thus he started to adopt the examination system and fully adopt Confucian examination content and the Chinese writing system.So later he also be dispatched by Emperor Guangzong as an official ambassador to Korea, and delivered these system and culture to Korea.

The Koryŏ dynasty, which lasted nearly 500 years, in fact, so its civilization exam system was actually a combination among the different type of imperial examination system the Tang, Five Dynasties, Song, and Yuan dynasties.

The imperial examination system implemented by China was introduced into Korea, which was not only inseparable from the close exchanges and deepening commercial relations between the two countries, but also had an important relationship with the ruling class of Korea at that time. The reason why the imperial examination system became popular in Korea was because of the strong support and advocacy of the Korean government at the time. The imperial examination system is in line with the idea of the ruling class to manage the country, incorporates the idea of self-development in Korea, encourages more Korean scholars and intellectuals to safeguard the interests of the Korean ruling government, and has caused the pursuit of equality in Korean culture and academic excellence of booming thought.

The thought process made people, even generals, like to write something to express their ideas. That is why in that period, at beginning, the sijo is only to be written by yangban, who went through a long and difficult process of education, but in the later period, there were many anonymous sijos to come out. Instead of using Chinese words, they used their own language and made it with more mordane but with a deep heart-touched sijo. The adoption of the civil service examination system is first helpful for the emperor to regulate the country and pick up the talented people, but then it transits into the path that made people’s minds free. No more could they only obey rules, but try to battle the constriction of a hard language, be creative, active, and likely to express themselves.

Notes

- "단군조선" [Dangun Joseon]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "위만조선" [Wiman Joseon]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Simons 1999, pp. 75–78

- Injae, Lee; Miller, Owen; Jinhoon, Park; Hyun-Hae, Yi (2014-12-15). Korean History in Maps. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107098466.

- "고구려·수 전쟁" [Goguryeo - Sui War]. National Institute of Korean History (in Korean). Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Lee, Ki-Baik (1984). A new history of Korea. Harvard University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780674615762.

References

- Simons, G. L. (1999), Korea: The Search for Sovereignty, Palgrave MacMillan

- Alston, Dane. 2008. “Emperor and Emissary: The Hongwu Emperor, Kwŏn Kŭn, and the Poetry of Late Fourteenth Century Diplomacy”. Korean Studies 32. University of Hawai'i Press: 104–47. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23718933.

- Kye, Seung B.. 2010. “Huddling Under the Imperial Umbrella: A Korean Approach to Ming China in the Early 1500s”. The Journal of Korean Studies 15 (1). University of Washington Center for Korea Studies: 41–66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41490257.

- Robinson, David M.. 2004. “Disturbing Images: Rebellion, Usurpation, and Rulership in Early Sixteenth-century East Asia—korean Writings on Emperor Wuzong”. The Journal of Korean Studies 9 (1). University of Washington Center for Korea Studies: 97–127. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41485331.

- Robinson, Kenneth R.. 1992. “From Raiders to Traders: Border Security and Border Control in Early Chosŏn, 1392—1450”. Korean Studies 16. University of Hawai'i Press: 94–115. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23720024.

- Rogers, Michael C.. 1959. “Factionalism and Koryŏ Policy Under the Northern Sung”. Journal of the American Oriental Society 79 (1). American Oriental Society: 16–25. doi:10.2307/596304. https://www.jstor.org/stable/596304

- Rogers, Michael C.. 1961. “Some Kings of Koryo as Registered in Chinese Works”. Journal of the American Oriental Society 81 (4). American Oriental Society: 415–22. doi:10.2307/595688. https://www.jstor.org/stable/595688

.svg.png)