Budapest–Belgrade railway

The Budapest–Belgrade railway connects the capital cities of Hungary and Serbia – the Budapest Keleti railway station with the new Belgrade Centre railway station.

As a $2.89 billion, 350 km (220 mi) high-speed rail line project, the Budapest–Belgrade railway is also a part, and first stage, of the planned Budapest–Belgrade–Skopje–Athens railway international connection in Central and Southeast Europe, a Chinese-CEE "hallmark" project of Beijing's Belt and Road initiative, connecting the China-run Piraeus port in Greece with the "heart" of Europe.[1]

Route, geography and landscapes

The railway line between Budapest and Belgrade passes mainly the Bács-Kiskun County and the Serbian Province of Vojvodina. The landscape is characterised by countless fields, dead straight highways and endless widths.[2]

Track condition, modernization

The outdated railway between Belgrade and Budapest will be modernised. The travel time should be decreased from eight hours to three and a half hours, and the maximum speed of the track is designed to be 200 km/h (120 mph). Train speed will be however limited to 160 km/h, due to signalling, so the line will not be high-speed at all., [3][4][5][6][7] According to the plans, the track should be modernised by early 2023.[8]

Modernization of the Hungarian section

The Hungarian section (152 km (94 mi)) of the project was announced in 2015 to cost HUF 472 billion and expected to be completed as of 2017–2018.[9][10] Currently it is expected to cost HUF 949 billion ($3.6 billion) with interest.

In Hungary, the project is carried out by Kínai-Magyar Vasúti Nonprofit Zrt (Chinese-Hungarian Railway Nonprofit Ltd.), a Hungarian-Chinese joint venture of MÁV Zrt. with China Railway International Corporation (CRIC) and China Railway International Group (CRIG).[6][11][12] According to one estimate, the works on this section could begin in 2021, as one year is needed for the public procurement procedures, and two years for the planning and negotiation phase.[13] The investment is widely criticised as it will never recover its costs, it is estimated that the investment could only show a return in 2400 years.[14]

Modernization of the Serbian section

In Serbia (some 200 km (120 mi)), one of the segments, the 34.5 km (21.4 mi)-long section Belgrade-Stara Pazova is currently being reconstructed by China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) together with China Railways International (CRI), with the investment of $350.1 million, funded with a loan from the Export-Import Bank of China.[15][16] The section Stara Pazova-Novi Sad is being reconstructed by the Russian RZD International, financed with Russian credit.[16] The reconstruction of the section Novi Sad-Subotica is set to begin in 2019, with estimated cost of €943 million, built by CCCC[[17]] and a duration of 33 months, during which this section will be closed.[18]

Criticism

In Hungary, the project is criticized for its unclear economic viability, debt to China, the fact that this is the most expensive infrastructure investment in the country's recent history, the proposed trajectory, and possible corruption.

While the Hungarian government classified its analysis for the economic viability of the project for 10 years,[19] estimates in the non-government-owned media estimate the return around 130[20] to 2400[21] years based on the current and expected traffic on the line.[22][23]

The track avoids all major Hungarian cities after Budapest, while an alternative route via Kecskemét and Szeged would benefit a ten-times bigger population.[24]

Only two consortia bid for the work. The winning consortium was announced June 2019. As with most public works since 2015[25][26] the government linked Hungarian entrepreneur, Lőrinc Mészáros[27] won, with his company “RM International Zrt”, alongside with two Chinese companies: China Tiejiuju Engineering & Construction LLC., and Railway Electrification Engineering Group LLC.[28]

The port of Piraeus is still 4 to 8 days away by train from Belgrade, the 4 hours of saved travel time on the leg to Budapest are negligible. COSCO can already transport everything, so this new railway can't really help them.[29]

History

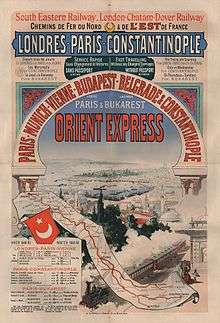

The railway line between Budapest and Belgrade was used also by the Orient Express until 1914. The Orient Express was launched on 5 June 1883. It connected Paris and Constantinople.

See also

- Budapest–Belgrade–Skopje–Athens railway

- Trans-European Transport Networks (TEN-T)

References

- Another Silk Road fiasco? China's Belgrade to Budapest high-speed rail line is probed by Brussels, by Wade Shepard, Forbes February 25, 2017

- "Vojvodina: Eigensinnige Provinz an der Donau". Die Presse (in German). Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- Magyar Építők https://magyarepitok.hu/aktualis/2019/06/igy-epul-meg-a-budapest-belgrad-gyorsvasut-az-orszaghatarig. Retrieved 20 December 2019. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - The Diplomat https://thediplomat.com/2018/01/who-benefits-from-the-chinese-built-hungary-serbia-railway/. Retrieved 1 November 2019. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Budapest – Belgrade reconstruction contract to be awarded in May https://www.railjournal.com/regions/europe/budapest-belgrade-reconstruction-contract-to-be-awarded-in-may/. Retrieved 1 November 2019. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Hungary kicks off USD 3.6 billion Belgrade-Budapest rail line investment". The Budapest Beacon. 2017-11-27. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- "China and Serbia agree deal to build $1.1bn Belgrade-Budapest high speed rail link". www.constructionglobal.com. Retrieved 2019-06-18.

- "Serbia starts upgrade of first section of Belgrade-Budapest railway line | | Central European Financial Observer". financialobserver.eu. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- "Intergovernmental agreement on the modernisation of the Belgrade-Budapest railway line has been initialled in Beijing". Government. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- "Még az idén megkezdődhet a Budapest-Belgrád vasútvonal modernizálása". Kormányzat. Retrieved 2019-06-10.

- Chinese-Hungarian Railway Nonprofit Ltd.: Chinese-Hungarian Railway Non-Profit Private Limited Company, in Hungarian: Kínai-Magyar Vasúti Nonprofit Zrt.: Kínai-Magyar Vasúti Nonprofit Zártkörűen Működő Részvénytársaság, November 10, 2016, on the MÁV website mavcsoport.hu)

- "Hungary expects bids for Belgrade-Budapest railway works in March". seenews.com. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- Diplomat, Zoltán Vörös, The. "Who Benefits From the Chinese-Built Hungary-Serbia Railway?". The Diplomat. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- Index.hu https://index.hu/gazdasag/2017/12/01/budapest_belgrad_megterules_vam_kereskedelem_pireusz_kina_131_ev/. Retrieved 2019-12-20. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Serbia starts Belgrade-Stara Pazova railway overhaul - govt". seenews.com. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- "Russia's RZD to start overhaul of part of Belgrade-Budapest railway in July". seenews.com. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- http://www.ccccltd.cn/news/gsyw/201807/t20180711_93434.html

- Hajnalka, Miklós. "Brze pruge i savremene železničke stanice". Magyar Szó Online. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- ATV. "Budapest-Belgrád vasútvonal: Miért titkolózik a kormány?". ATV.hu. Retrieved 2019-06-10.

- Tamás, Mészáros (2017-12-01). "130 év alatt térülhet meg a méregdrága kínai vasút". index.hu (in Hungarian). Retrieved 2019-06-10.

- "2400 év alatt térülhet meg Orbán vasútja". Figyelő online. Retrieved 2019-06-10.

- "IHO - Vasút - Százhatvanra alkalmas, évezredek alatt térül meg – mi az?". iho.hu. Retrieved 2019-06-10.

- "Budapest–Kunszentmiklós-Tass–Kelebia-vasútvonal", Wikipédia (in Hungarian), 2019-06-02, retrieved 2019-06-10

- "A Budapest-Belgrád vasútvonal felújítása", Wikipédia (in Hungarian), 2019-06-10, retrieved 2019-06-10

- "Subscribe to read". Financial Times. Retrieved 2019-06-10.

- "Viktor Orban's oligarchs: a new elite emerges in Hungary". archive.fo. 2017-12-21. Archived from the original on 2017-12-21. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- "Lőrinc Mészáros". The Orange Files. 2016-06-01. Retrieved 2019-06-10.

- "Mészáros firm among winners of massive rail contract". Budapest Business Journal. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- Bálint, Szalai (8 December 2017). "A kínaiaknak pont tökmindegy a Budapest–Belgrád-vasút". index.hu (in Hungarian). Retrieved 1 November 2019.