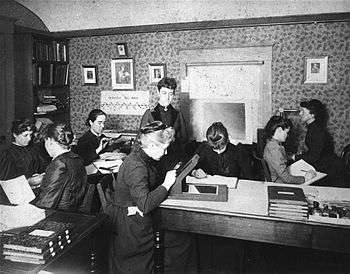

Harvard Computers

The Harvard Observatory, under the direction of Edward Charles Pickering (1877 to 1919) had a number of women working as skilled workers to process astronomical data. Harvard was the first such institution to hire women to do this type of work. Among these women were Williamina Fleming, Annie Jump Cannon, Henrietta Swan Leavitt, Florence Cushman and Antonia Maury. Although these women started primarily as calculators, they often rose to contribute to the astronomical field, and even publish in their own names. This staff came to be known as the Harvard Computers or, more derisively, as "Pickering's Harem".[1][2] This was an example of what has been identified as the "harem effect" in the history and sociology of science.

History

Although Pickering believed that gathering data at astronomical observatories was not the most appropriate work, it seems that several factors contributed to his decision to hire women instead of men.[3] Among them was the fact that men were paid much more than women, so he could employ more staff with the same budget. This was relevant in a time when the amount of astronomical data was surpassing the capacity of the Observatories to process it.[4] Although some of Pickering's female staff were astronomy graduates, their wages were similar to those of unskilled workers. They usually earned between 25 and 50 cents per hour, more than a factory worker but less than a clerical one.[5] Pickering also argued that women would be advantageous workers due to the amount of free time they often possessed, many had an inclination to astronomy and science, and the work could be done from any window.[3]

The women were often tasked with measuring the brightness, position, and color of stars.[6] The work was mainly clerical, including such tasks as classifying stars by comparing the photographs to known catalogs and reducing the photographs while accounting for things like atmospheric refraction in order to render the clearest possible image. Fleming herself described the work as “so nearly alike that there will be little to describe outside ordinary routine work of measurement, examination of photographs, and of work involved in the reduction of these observations”.[6] At times women offered to work at the observatory for free in order to gain experience in a field that was difficult to get into.[2]

Mary Anna Palmer Draper

Mrs. Draper was the widow of Dr. Henry Draper, an astronomer who died before completing his work on the chemical composition of stars.[3] She was very involved in her husband's work and wanted to finish his classification of stars after he passed away.[3] Mrs. Draper quickly realized the task facing her was far too daunting for one person. She had received correspondence from Mr. Pickering, a close friend of hers and her husband's. Pickering offered to help finish her husband's work, and encouraged her to publish his findings up to the time of his death.[3] After some deliberation and much consideration, Mrs. Draper decided in 1886 to donate money and a telescope of her husband's to the Harvard Observatory in order to photograph the spectra of stars. She had decided this would be the best way to continue her husband's work and erect his legacy in astronomy.[3] She was very insistent on funding the memorial project with her own inheritance, as it would carry on her husband's legacy. She was a dedicated follower of the observatory and a great friend of Pickering's. In 1900 she funded an expedition to see the total solar eclipse occurring that year.[3]

Williamina Fleming

Williamina Fleming had no prior relation to Harvard, as she was a Scottish immigrant[3] working as Pickerig's housemaid. Her first assignment was to improve an existing catalog of stellar spectra. Fleming went on to help develop a classification of stars based on their hydrogen content, as well as play a major role in discovering the strange nature of white dwarf stars.[6] Williamina continued her career in astronomy when she was appointed Harvard's Curator of Astronomical Photographs in 1899, also known as Curator of the Photographic Plates. She remained the only woman curator until the 1950s.[7] Her work also led to her becoming the first female American citizen to be elected to the Royal Astronomical Society in 1907.[8]

Antonia Maury

Antonia Maury was the niece of Henry Draper, and after some recommendation from Mrs. Draper, was hired as a computer.[3] She was a graduate from Vassar College, and was tasked with reclassifying some of the stars after the publication of the Henry Draper Catalog. Maury decided to go further and improved and redesigned the system of classification, but had other obligations and left the observatory in 1892 then again in 1894. Her work was finished with the help of Pickering and the computing staff and was published in 1897.[3] She returned again in 1908 as an associate researcher.[3]

Anna Winlock

Some of the first women who were hired to work as computers had familial connections to the Harvard Observatory’s male staff. For instance, Anna Winlock, one of the first of the Harvard Computers, was the daughter of Joseph Winlock, the third director of the observatory and Pickering’s immediate predecessor.[9] Anna Winlock joined the observatory in 1875 to assist in supporting her family after her father's unexpected passing. Within a year, three other women joined the staff: Selina Bond, Rhoda Sauders, and a third, who was likely a relative of an assistant astronomer.[10]

Annie Cannon

Pickering decided to hire Annie Jump Cannon, a graduate of Wellesley College, to classify the southern stars. While at Wellesley, she took astronomy courses from one of Pickering's star students, Sarah Frances Whiting.[3] Astronomy became a big part of her life, and helped her grieve her mother's passing.[3] She became the first female assistant to study variable stars at night.[3] She studied the "light curve" of variable stars which could help suggest the type and causation of variation.[3] Cannon considered merging the classification systems developed by Fleming and Maury rather than inventing a brand new one, and developed the Harvard Classification Scheme, which constitutes the basis of the system used today. She also categorized the variable stars into tables so they could be identified and compared more easily.[3] The importance of these systems is that the light of stars relates to the temperature of the stars. The basis of her system is that stars are separated by letters then sub-divided by numbers.

Annie Cannon was one of the more famous people out of all the computers of her group. She is known for being the first female scientist to be recognized for many awards and titles in her field of study. She was the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Oxford. She was also the first woman to receive the Henry Draper Medal from the National Academy of Sciences. She was the first female officer in the American Astronomical Society. Cannon went on to establish her very own Annie Jump Cannon Award. This award is given to women who show outstanding research and promise future research in postdoctoral work. Annie Cannon leaves a legacy for women to achieve dreams that she also fought for.

Henrietta Leavitt

Henrietta Swan Leavitt arrived at the observatory in 1893. She had experience through her college studies, traveling abroad, and teaching. In academia, Leavitt excelled in mathematics courses at Cambridge.[3] When she began working at the observatory she was tasked with measuring star brightness through photometry.[3] She returned to the observatory in 1903 after trips to Europe and experience as an art assistant at Beloit College.[3] She found hundreds of new variable stars after starting to analyze the Great Nebula in Orion. Her work proved successful and was expanded to study the variables of the entire sky with Annie Cannon and Evelyn Leland.[3] With her experience in photometry, Leavitt used her skills to compare stars in different exposures. While doing this, she discovered that some stars have the same brightness no matter the distance. This discovery led to her developing a direct way to calculate a star's distance from earth using the period of Cepheid variable stars and their intrinsic brightness.[11] This discovery, in turn, led to the modern understanding of the true size of the universe, and Cepheid variables are still an essential tool for the measurement of cosmological distance.

Sadly, Leavitt does not receive as much credit as she deserves. Pickering published her work with his name on it. The legacy she left allowed future scientists to further discoveries in space. Astronomer Edwin Hubble used Leavitt's information to calculate the distance of the nearest galaxy to the earth, the Andromeda Galaxy. This led to the realization that there are even more galaxies than previously thought.

References

- ↑ Larsen, Kristine M. (2007). Cosmology 101. Greenwood. ISBN 0313337314.

- 1 2 Sobel, Dava (2016). The Glass Universe. Viking. pp. xii. ISBN 9780698148697.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Sobel, Dava (2016). The Glass Universe. Viking. pp. xii. ISBN 9780698148697.

- ↑ Rossiter, Margaret W. (2006). Women Scientists in America. I. JHU Press. ISBN 0801857112.

- ↑ Johnson, George (2006). Miss Leavitt's Stars. W. W. Norton. ISBN 0393328562.

- 1 2 3 Geiling, Natasha. "The Women Who Mapped the Universe And Still Couldn’t Get Any Respect", Smithsonian.com, 18 September 2013. Retrieved on 12 October 2017.

- ↑ Hoffleit, E. Dorrit (2002-12-01). "Pioneering Women in the Spectral Classification of Stars". Physics in Perspective. 4 (4): 370–398. Bibcode:2002PhP.....4..370H. doi:10.1007/s000160200001. ISSN 1422-6944.

- ↑ Nelson, Sue (2008-09-03). "The Harvard computers". Nature. 455 (7209): 36–37. Bibcode:2008Natur.455...36N. doi:10.1038/455036a.

- ↑ Sobel, Dava (2016). The Glass Universe. Viking. p. 9. ISBN 9780698148697.

- ↑ Grier, David Alan (2008). When Computers Were Human. Princeston University Press. p. 82. ISBN 9781400849369.

- ↑ Leavitt, Henrietta S.; Pickering, Edward C. (1912). "Periods of 25 Variable Stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud". Harvard College Observatory Circular. 173: 1–3. Bibcode:1912HarCi.173....1L.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harvard Computers. |