Tooth whitening

Tooth whitening (termed tooth bleaching when utilising bleach), is either the restoration of a natural tooth shade or whitening beyond the natural shade.

Restoration of the underlying natural tooth shade is possible by simply removing surface stains caused by extrinsic factors, stainers such as tea, coffee, red wine and tobacco. The buildup of calculus and tartar can also influence the staining of teeth. This restoration of the natural tooth shade is achieved by having the teeth cleaned by a dental professional (commonly termed "scaling and polishing"), or at home by various oral hygiene methods. Calculus and tartar are difficult to remove without a professional clean.

To whiten the natural tooth shade, bleaching is suggested. It is a common procedure in cosmetic dentistry, and a number of different techniques are used by dental professionals. There is a plethora of products marketed for home use to do this also. Techniques include bleaching strips, bleaching pens, bleaching gels and laser tooth whitening. Bleaching methods generally use either hydrogen peroxide or carbamide peroxide which breaks down into hydrogen peroxide.

Natural tooth shade

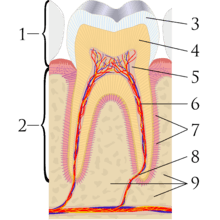

The perception of tooth color is the result of a complex interaction of factors such as: lighting conditions, translucency, opacity, light scattering, gloss, the human eye and brain.[1] Teeth are composed of a surface enamel layer, which is whiter and semitransparent, and an underlying dentin layer, which is darker and less transparent. These are calcified, hard tissues comparable to bone. The natural shade of teeth is best considered as such; an off-white, bone-color rather than pure white. Public opinion of what is normal tooth shade tends to be distorted. Portrayals of cosmetically enhanced teeth are common in the media. In one report, the most common tooth shade in the general population ranged from A1 to A3 on the VITA classical A1-D4 shade guide.[2]

Females generally have slightly whiter teeth than males, partly because females' teeth are smaller, and therefore there is less bulk of dentin, partially visible through the enamel layer. For the same reason, larger teeth such as the molars and the canine (cuspid) teeth tend to be darker. Baby teeth (deciduous teeth) are generally whiter than the adult teeth that follow, again due to differences in the ratio of enamel to dentin. As a person ages the adult teeth often become darker due to changes in the mineral structure of the tooth, as the enamel becomes less porous and phosphate-deficient. The enamel layer may also be gradually thinned or even perforated by the various forms of tooth wear.

Tooth staining and discoloration

Teeth may be darkened by a buildup of surface stains (extrinsic staining), which hides the natural tooth color; or the tooth itself may discolor (intrinsic staining).[3]

Extrinsic discolouration

Extrinsic stains can become internalised through enamel defects or cracks or as a result of dentine becoming exposed but most extrinsic stains appear to be deposited on or in the dental pellicle.[4] Causes of extrinsic staining include:

- Dental plaque: although usually virtually invisible on the tooth surface, plaque may become stained by chromogenic bacteria such as Actinomyces species.[5]

- Calculus: neglected plaque will eventually calcify, and lead to the formation of a hard deposit on the teeth, especially around the gumline. The color of calculus varies, and may be grey, yellow, black or brown[5]

- Tobacco: tar in smoke from tobacco products (and also smokeless tobacco products) tends to form a yellow-brown-black stain around the necks of the teeth above the gumline[5]

- Betel chewing.[6]

- Certain foods and drinks. food-goods and vegetables rich with carotenoids or xanthonoids. Ingesting colored liquids like sports drinks, cola, coffee, tea, and red wine can discolor teeth.[7]

- Certain topical medications. Chlorhexidine (antiseptic mouthwash) binds to tannins, meaning that prolonged use in persons who consume coffee, tea or red wine is associated with extrinsic staining (i.e. removable staining) of teeth.[8]

- Metallic compounds. Exposure to such metallic compounds may be in the form of medication or other environmental exposure. examples include iron (black stain), iodine (black), copper (green), nickel (green), cadmium (yellow-brown).[3]

Intrinsic discolouration

Changes in the thickness of the dental hard tissues would result in intrinsic discolouration. There are a few causal factors that may act locally or systematically, affecting only a single tooth or all teeth and cause discolouration as a result. Several diseases that are known to affect the developing dentition especially during enamel and dentine formation can lead to discolouration.[9] Causes of intrinsic staining include:

- Dental caries (tooth decay)[6]

- Dental trauma[6] which may cause staining either as a result of pulp necrosis or internal resorption. Alternatively the tooth may become darker without pulp necrosis

- Enamel hypoplasia

- Hyperemia

- Fluorosis[3]

- Dentinogenesis imperfecta[3]

- Amelogenesis imperfecta[3]

- Tetracycline and minocycline. Tetracycline is a broad spectrum antibiotic,[10] and its derivative minocycline is common in the treatment of acne.[11] The drug is able to chelate calcium ions and is incorporated into teeth, cartilage and bone.[10] Ingestion during the years of tooth development causes yellow-green discoloration of dentine visible through the enamel which is fluorescent under ultraviolet light. Later, the tetracycline is oxidized and the staining becomes more brown and no longer fluoresces under UV light.[5][12]

- Porphyria[5]

- Hemolytic disease of the newborn[5]

- Root resorption[9]

- Alkaptonuria:[9] Metabolic disorder which promotes the accumulation of homogentisic acid in the body and may cause brown colour pigmentation in the teeth, gums and buccal mucosa.[13]

Causes of extrinsic and intrinsic staining include:

- Age: the tooth enamel becomes thinner over time, which allows the dentine to shine through.[14]

- Bruxism (clenching and grinding of the teeth) can lead to micro-cracking of the incisal edges of the teeth. Extrinsic stains may settle more readily into these cracks, and a thin layer of enamel can be left. This thin enamel layer is partially transparent, allowing the dark background of the mouth to shine through, affording a darker appearance of the incisal edge.

Methods

Whitening methods can usually be divided into two types. The first type includes methods that removes surface stains from teeth and includes toothpastes, air polishing and micro abrasion. The second type removes stains that have penetrated the enamel and therefore cannot be removed by the first type. The second type is referred to as "bleaching", typically using either hydrogen peroxide or carbamide peroxide which breaks down into hydrogen peroxide.

Bleaching solutions generally contain hydrogen peroxide or carbamide peroxide, which bleaches the enamel dentine junction to change its color.[15] The peroxide penetrates the porosities in the rod-like crystal structure of enamel and breaks down stain deposits in the dentin.

In-office

Before the treatment, the dentist may examine the patient: taking a health and dental history (including allergies and sensitivities), observe hard and soft tissues, placement and conditions of restorations, and sometimes x-rays to determine the nature and depth of possible irregularities.

The whitening shade guides are used to measure tooth color. These shades determine the effectiveness of the whitening procedure, which may vary from two to seven shades.[16] The effects of bleaching can last for several months, but may vary depending on the lifestyle of the patient. Consuming tooth staining foods or drinks that have a strong colour may compromise effectiveness of the treatment. These include; coffee, fizzy drinks, red-colored sauces etc.

In-office bleaching procedures generally use a light-cured protective layer that is carefully painted on the gums and papilla (the tips of the gums between the teeth) to reduce the risk of chemical burns to the soft tissues. The bleaching agent is either carbamide peroxide, which breaks down in the mouth to form hydrogen peroxide, or hydrogen peroxide itself. The bleaching gel typically contains between 10% and 44% carbamide peroxide, which is roughly equivalent to a 3% to 16% hydrogen peroxide concentration. The legal percentage of hydrogen peroxide allowed to be given is 0.1-6%. Bleaching agents are only allowed to be given via dental practitioners, dental therapists and dental hygienists.

Bleaching is least effective when the original tooth color is grayish and may require custom bleaching trays. Bleaching is most effective with yellow discolored teeth. If heavy staining or tetracycline damage is present on a patient's teeth, and whitening is ineffective (tetracycline staining may require prolonged bleaching, as it takes longer for the bleach to reach the dentine layer), there are other methods of masking the stain. Bonding, which also masks tooth stains, is when a thin coating of composite material is applied to the front of a person's teeth and then cured with a blue light. A veneer can also mask tooth discoloration.

The advantages of this technique are that the results happen at one sitting at the dentist, it does not take a longer time for results to show like it does when the home bleaching technique is used. This is good if fast, effective results are required.

However the disadvantages of this technique is that this is a one off treatment and if further whitening is needed the treatment will need to be carried out all over again. However, with at home bleaching, more bleaching gel can be purchased from the dentist and the same trays can be used, as long as they are intact and have no holes in them.

Light-accelerated bleaching

Power or light-accelerated bleaching, sometimes colloquially referred to as laser bleaching (a common misconception since lasers are an older technology that was used before current technologies were developed), uses light energy which is intended to accelerate the process of bleaching in a dental office. Different types of energy can be used in this procedure, with the most common being halogen, LED, or plasma arc. Use of light during bleaching increases the risk of tooth sensitivity and may not be any more effective than bleaching without light when high concentrations of hydrogen peroxide are used.[17] Recent research has shown that the use of a light activator does not improve bleaching, has no measurable effect and most likely to increase the temperature of the associated tissues, resulting in damage.[18][19]

The ideal source of energy should be high energy to excite the peroxide molecules without overheating the pulp of the tooth.[20] Lights are typically within the blue light spectrum as this has been found to contain the most effective wavelengths for initiating the hydrogen peroxide reaction. A power bleaching treatment typically involves isolation of soft tissue with a resin-based, light-curable barrier, application of a professional dental-grade hydrogen peroxide whitening gel (25-38% hydrogen peroxide), and exposure to the light source for 6–15 minutes. Recent technical advances have minimized heat and ultraviolet emissions, allowing for a shorter patient preparation procedure.

In-office, the teeth are polished using pumice, the bleaching agent is added. The teeth are washed with a lot of water then polished again.

It is recommended to avoid smoking, drinking red wine, eating or drinking any deeply coloured foods after this as the teeth may stain considerably straight after treatment.

Nanoparticle Catalysts for Reduced Hydrogen Peroxide Concentration

A recent addition to the field is new light-accelerated bleaching agents containing lower concentrations of hydrogen peroxide with a titanium oxide nanoparticle based catalyst. Reduced concentrations of hydrogen peroxide cause lower incidences of tooth hypersensitivity.[21] The nanoparticles act as photocatalysts, and their size prevents them from diffusing deeply into the tooth. When exposed to light, the catalysts produce a rapid, localized breakdown of hydrogen peroxide into highly reactive radicals. Due to the extremely short lifetimes of the free radicals, they are able to produce bleaching effects similar to much higher concentration bleaching agents within the outer layers of the teeth where the nanoparticle catalysts are located. This provides effective tooth whitening while reducing the required concentration of hydrogen peroxide and other reactive byproducts at the tooth pulp.

Internal bleaching on non-vital teeth.

Internal staining of dentine can discolor the teeth from inside out. Internal bleaching can remedy this on root canal treated teeth. Internal bleaching procedures are performed on devitalized teeth that have undergone endodontic treatment (root canal treatment) but are discolored due to internal staining of the tooth structure by blood and other fluids that leaked in. Unlike external bleaching, which brightens teeth from the outside in, internal bleaching brightens teeth from the inside out. Bleaching the tooth internally involves drilling a hole to the pulp chamber no more than 2mm below the gingival margin, cleaning any infected or discoloured dentine, sealing, and filling the root canal with gutta-percha points, cleaning the inside of the canal using etchant and placing a peroxide gel or sodium perborate tetrahydrate into the pulp chamber so they can work directly inside the tooth on the dentine layer. In this variation of whitening the whitening agent is sealed within the tooth over a period of some days and replaced as needed, the so-called "walking bleach" technique.. A seal should be placed over the root filling material to minimise microleakage. There is a small risk of external resorption.

An alternative to the walking bleach procedure is the inside-out bleach where the bleaching cavity is left open and the patient issued with a custom-formed tray to place and retain the agent, typically a carbamide peroxide gel inside the cavity. The patient changes the gel over 24 hours and uses a tray to retain it, they return to the dentist where this is sealed. On review once sufficient shade change has occurred the access cavity can be sealed, typically with a dental composite.

At home

At-home whitening methods include gels, chewing gums, rinses, toothpastes, paint-on films, and whitening strips.[22][23] Most over-the-counter methods utilize either carbamide peroxide or hydrogen peroxide.[23] Although there is some evidence that such products will whiten the teeth compared to placebo, the majority of the published scientific studies were short term and are subject to a high risk of bias as the research was sponsored or conducted by the manufacturers.[23] There is no long term evidence of the effectiveness or potential risks of such products.[23] Any demonstrable difference in the short term efficiency of such products seems to be related to concentration of the active ingredient.[23]

Night-guard vital bleaching

Night guard vital bleaching is another increasingly popular method of dentist prescribed at home teeth whitening. These methods have gained popularity due to the fact that significant results can be achieved overnight without the removal of any tooth tissue making it a conservative method of lightening tooth shade.The process of night guard vital bleaching involves alginate impressions of the patients’ teeth in the first visit, this is then casted into stone and a custom-made vacuum form tray is made. The patient is provided with bleaching solution, which is placed into the tray for use overnight. The number of nights the tray is used would be dependent on the extent of staining and the shade desired by the patient. Due to the recent spike in the use of home teeth whitening products there is a lack of research regarding long term implications such as side effects and duration of results. Research has found that ‘nightguard vital bleaching is a safe, effective, and predictable method to lighten teeth. The whitening effect lasted up to 47 months in 82% of the patients, with no adverse side effects reported at the end of the study’.[24]

Whitening toothpastes

Whitening toothpastes are different to regular toothpastes in a way that they contain a higher content of abrasives and detergents to fight off tougher stains. Most contain low concentrations of carbamide/hydrogen peroxide rather than bleach – this lightens the colour of teeth. These whitening toothpastes make teeth one to two shades lighter.[25] Toothpastes (dentifrices) which are advertised as "whitening" rarely contain carbamide peroxide, hydrogen peroxide or any other bleaching agent.[26] Rather, they are abrasive (usually containing alumina, dicalcium phosphate dehydrate, calcium carbonate or silica), intended to remove surface stains from the tooth surface.[26] Sometimes they contain enzymes purported to break down the biofilm on teeth.[26] Unlike bleaches, whitening toothpaste does not alter the intrinsic color of teeth. Excessive or long term use of abrasive toothpastes will cause dental abrasion, thinning the enamel layer[26] and slowly darkening the appearance of the tooth as the dentine layer becomes more noticeable. An alternative method of whitening at home, which competes with the use of a whitening paste, is the use of a patent whitening mouthwash. The mouthwash shows marginally better efforts at whitening compared to the use of paste.[27]

Over-the-counter (OTC) Whitening Strips and Gels

Whitening strips work by the placement of a layer of peroxide gel on the labial surfaces of teeth through the use of plastic strips that are shaped to fit there. Many different types of whitening strips are available on the market, after being introduced in the late 1980s.[28] Each variety of whitening strips has its own set of instructions to suit the product, for example, different strips can be used at different frequencies to reach the same whitening end point.

Whitening gels are also peroxide based, like the strips, and applied straight onto the tooth surfaces via the use of a small brush. Following manufacturer’s instructions they can lighten teeth by 1-2 shades.[28]

Whitening Rinses

Another method used by people at home to whiten teeth is the use of whitening rinses - these contain oxygen sources, like hydrogen peroxide. To see a 1 -2 improvement in tooth shade could take up to 3 months.[28]

Natural (alternative) methods

One purported method of naturally whitening the teeth is through the use of malic acid.[29][30] The juice of apples, especially green apples, contains malic acid. On the other hand, excessive consumption of acidic beverages will slowly dissolve the enamel layer, making the underlying yellower dentine show through more noticeably, leading to darkening of the tooth's appearance. One study indicates that malic acid is a weak tooth whitening agent.[31]

Indications

- Generalized staining of teeth

- Extrinsic staining caused by smoking or diet

- Fluorosis

- White and brown spots

- Tetracycline staining, although discolouration may not be fully corrected

Contra-indications

Some groups are advised to carry out tooth whitening with caution as they may be at higher risk of adverse effects.

- Patients with unrealistic expectations

- Allergic to peroxide

- Pre-existing sensitive teeth

- Cracks / exposed dentine

- Enamel development defects

- Acid erosion

- Receding gums (gingival recession) and yellow roots, as roots do not bleach as readily as crowns

- Sensitive gums

- Defective dental restorations

- Tooth decay. White-spot decalcification may be highlighted and become more noticeable directly following a whitening process, but with further applications the other parts of the teeth usually become more white and the spots less noticeable.

- Active periapical pathology

- Untreated periodontal disease

- Pregnant or lactating women

- Children under the age of 16. This is because the pulp chamber, or nerve of the tooth, is enlarged until this age. Tooth whitening under this condition could irritate the pulp or cause it to become sensitive. Younger people are also more susceptible to abusing bleaching.[26]

- Persons with visible white fillings or crowns. Tooth whitening does not usually change the color of fillings and other restorative materials. It does not affect porcelain, other ceramics, or dental gold. However, it can slightly affect restorations made with composite materials, cements and dental amalgams. Tooth whitening will not restore color of fillings, porcelain, and other ceramics when they become stained by foods, drinks, and smoking, as these products are only effective on natural tooth structure. As such, a shade mismatch may be created as the natural tooth surfaces increase in whiteness and the restorations stay the same shade. Whitener does not work where bonding has been used and neither is it effective on tooth-color filling. Other options to deal with such cases are the porcelain veneers or dental bonding.[32]

Risks

The most common side effects associated with tooth bleaching are increased sensitivity of the teeth and irritation of the gums, which tend to resolve once the bleaching is stopped.[23]

Hypersensitivity

The low pH of bleach opens up dentinal tubules and may result in dentine hypersensitivity, bringing about hypersensitive teeth.[33] It manifests as increased sensitivity to stimuli such as hot, cold or sweet. 67 – 78% of the patients experience teeth sensitivity after in office bleaching with hydrogen peroxide in combination with heat.[34][35] Sensitivity of teeth can persist up to 4 days after teeth bleaching cessation.[36][37] However, it varies from person to person. A longer duration of hypersensitivity has been reported 39 days post-bleaching.[37]

Recurrent treatments or use of desensitising toothpastes may alleviate discomfort, though there may be occurrences where the severity of pain discontinues further treatment. Potassium nitrate and sodium fluoride are used to reduce tooth sensitivity following bleaching.[38]

Irritation of mucous membranes

Hydrogen peroxide is an irritant and cytotoxic. At concentrations of 10% or higher, hydrogen peroxide is potentially corrosive to mucous membranes or skin and can cause a burning sensation and tissue damage.[39] Chemical burns from gel bleaching (if a high-concentration oxidising agent contacts unprotected tissues, which may bleach or discolor mucous membranes). Tissue irritation most commonly results from an ill-fitting mouthpiece tray rather than the tooth-bleaching agent.

Uneven results

After teeth bleaching, it is normal to have uneven results. With time, the color will appear more even. To avoid this from happening it is important to avoid making some common post-bleaching mistakes, such as consuming foods and beverages that stain the surface of your teeth.

Return to original pre-treatment shade

Nearly half the initial change in color provided by an intensive in-office treatment (i.e., 1 hour treatment in a dentist's chair) may be lost in seven days.[40] Rebound is experienced when a large proportion of the tooth whitening has come from tooth dehydration (also a significant factor in causing sensitivity).[41] As the tooth rehydrates, tooth color "rebounds", back toward where it started.[42]

Over-bleaching

Overbleaching, known in the profession as "bleached effect", particularly with the intensive treatments (products that provide a large change in tooth colour over a very short treatment period, e.g., an hour). Too much bleaching will cause the teeth to appear very translucent.[43]

Damage to enamel

Home tooth bleaching treatments can have significant negative effects on tooth enamel.[44] Study has been done and there is evidence that high concentration of carbamide peroxide can damage the enamel surface. Although the effect on enamel is less detrimental than seen after phosphoric acid etch,[45] the increased roughness of the surface may make teeth more susceptible to extrinsic discolouration after bleaching.

Weakened dentin

Intracoronal bleaching with 30% hydrogen peroxide decreases the micro-hardness of dentin.[46] Thus, weakening the mechanical properties.

Effects on existing restorations

Dental Amalgam – Exposure to carbamide peroxide solutions increase mercury release for one to two days.[47][48]

Resin Composite – bond strength between enamel and resin based fillings weakened.[49]

Glass Ionomer and other cements – Study suggesting that solubility of these materials may increase.[50]

Bleachorexia

When bleaching is abused and an individual develops an unhealthy obsession with whitening, the term bleachorexia or whitening junky has been used.[26] The condition is characterized by repeated bleaching even though the teeth are already white and will not get any whiter.[43] This condition is somewhat similar to body dismorphic disorder. The individual perceives their teeth never to be white enough, despite repeated bleaching. A person with bleachorexia will typically continually request more bleaching services or products from the dental professional.[43] It has been recommended that a target shade be agreed before starting bleaching treatment to help with this problem.[43]

Other risks

Hydrogen peroxide might act as a tumour promoter.[51] Intracoronal internal bleaching may also cause cervical root resorption,[51] it is more commonly observed in teeth that are treated with thermo-catalytic bleaching method. Due to extensive removal of intracoronal dentin, tooth crown fracture can happen after intracoronal bleaching.[51]

The International Agency of Research on Cancer (IARC) has concluded that there is insufficient evidence for the carcinogeni-city of hydrogen peroxide. The chemical is now under Group 3: Unclassifiable as to carcinogenicity to humans.[52] The genotoxic potential of hydrogen peroxide has been evaluated recently. Oral health products that contain or release hydrogen peroxide up to 3.6% H2O2 is not likely to increase cancer risk in individuals.[53]

Maintenance

Although treatment results can be rapid, stains can reappear within the first few months and years of treatment. In order to maintain the whitened appearance, there are ways to protect the teeth and prolong the treatment.[54]

- Brush or rinse mouth immediately after eating and drinking[55]

- Chewing gum

- Floss to remove plaque

- Use whitening tooth paste once or twice a week to avoid surface stains

- Drink harsh beverages through a straw[56]

- Do touch up treatments

History

There has been interest in white teeth since ancient times.[43] Ancient Romans used urine and goat milk in an attempt to make and keep their teeth whiter. Guy de Chauliac suggested the following to whiten the teeth: "Clean the teeth gently with a mixture of honey and burnt salt to which some vinegar has been added."[43] In 1877 oxalic acid was proposed for whitening, followed by calcium hypochlorite.[43] Peroxide was first used for tooth whitening in 1884.[43]

Society and culture

Teeth whitening has become the most marketed and requested procedure in cosmetic dentistry. More than 100 million Americans whiten their teeth one way or another; spending an estimated $15 billion in 2010.[57] The US Food and Drug Administration only approves gels that are under 6% hydrogen peroxide or 16% or less of carbamide peroxide. The Scientific Committee for Consumer Protection of the EU consider gels containing higher concentrations than these to be unsafe.[58]

According to a European Council regulation, only a qualified dental professional can legally provide tooth whitening products using 0.1 - 6% hydrogen peroxide, and that the patient must be at least 18 years old.[59] Over recent years, there have been rising concerns over unlicensed staff providing poor quality tooth whitening treatment. Significant evidence has been gathered that tooth whitening procedures have been offered by beauty salons and health clinics under unskilled staff without dental qualifications.[60] A group of recognised dental boards and organisations called The Tooth Whitening Information Group (TWIG) was established to promote safe and productive tooth whitening information and guidance for the benefit of the public. Reports can be made by the public to TWIG through their website regarding any individual providing illegal tooth whitening services, or if they personally undergone treatment done by an incompetent staff who is not a dental professional.

In Brazil, all bleaching products are classed as cosmetics (Degree II) in legislature.[26] There are concerns that this will result in increasing misuse of bleaching products and consequently there have been calls for reclassification.[26]

See also

References

- ↑ Joiner, A (2004). "Tooth colour: a review of the literature". Journal of Dentistry. 32 (Suppl 1): 3–12. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2003.10.013. PMID 14738829.

- ↑ Herekar M; Mangalvedhekar M; Fernandes A (Dec 2010). "The Most Prevalent Tooth Shade in a Particular Population: A survey". Journal of the Indian Dental Association. 4 (12).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chi AC, Damm DD, Neville BW, Allen CA, Bouquot J (11 June 2008). Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 70–74. ISBN 978-1-4377-2197-3.

- ↑ Sharif, N; MacDonald, E; Hughes, J; Newcombe, R G; Addy, M (2000-06-10). "bleaching: The chemical stain removal properties of 'whitening' toothpaste products: studies in vitro". British Dental Journal. 188 (11): 620–624. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4800557. ISSN 1476-5373.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rajendran A; Sundaram S (10 February 2014). Shafer's Textbook of Oral Pathology (7th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences APAC. pp. 386, 387. ISBN 978-81-312-3800-4.

- 1 2 3 Crispian Scully (21 July 2014). Scully's Medical Problems in Dentistry. Elsevier Health Sciences UK. ISBN 978-0-7020-5963-6.

- ↑ "Facts About Tooth Staining and Discoloration". www.bhandaldentistry.co.uk. 2018-10-02. Retrieved 2017-09-28.

- ↑ Scully C (2013). Oral and maxillofacial medicine : the basis of diagnosis and treatment (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 39, 41. ISBN 9780702049484.

- 1 2 3 Watts, A; Addy, M (2001-03-24). "Tooth discolouration and staining: Tooth discolouration and staining: a review of the literature". British Dental Journal. 190 (6): 309–316. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4800959. ISSN 1476-5373.

- 1 2 Sánchez, AR; Rogers RS, 3rd; Sheridan, PJ (October 2004). "Tetracycline and other tetracycline-derivative staining of the teeth and oral cavity". International Journal of Dermatology. 43 (10): 709–15. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02108.x. PMID 15485524.

- ↑ Good, ML; Hussey, DL (August 2003). "Minocycline: stain devil?". The British Journal of Dermatology. 149 (2): 237–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05497.x. PMID 12932226.

- ↑ Ibsen OAC; Phelan JA (14 April 2014). Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-323-29130-9.

- ↑ Pratibha, K.; Seenappa, T.; Ranganath, K. (2007). "ALKAPTONURIC OCHRONOSIS : REPORT OF A CASE AND BRIEF REVIEW" (PDF). Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry. 22 (2): 158–161.

- ↑ "Tooth Discoloration". www.colgateprofessional.com. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

- ↑ "Hydrogen peroxide, in its free form or when released, in oral hygiene products and tooth whitening products" (PDF). European Union. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ↑ Delgado, E; Hernández-Cott, PL; Stewart, B; Collins, M; De Vizio, W (2007). "Tooth-whitening efficacy of custom tray-delivered 9% hydrogen peroxide and 20% carbamide peroxide during daytime use: A 14-day clinical trial". Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal. 26 (4): 367–72. PMID 18246965.

- ↑ He, LB; Shao, MY; Tan, K; Xu, X; Li, JY (August 2012). "The effects of light on bleaching and tooth sensitivity during in-office vital bleaching: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Dentistry. 40 (8): 644–53. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2012.04.010. PMID 22525016.

- ↑ Baroudi, Kusai; Hassan, Nadia Aly (2015). "The effect of light-activation sources on tooth bleaching". Nigerian Medical Journal. 55 (5): 363–8. doi:10.4103/0300-1652.140316. PMC 4178330. PMID 25298598.

The in-office bleaching treatment of vital teeth did not show improvement with the use of light activator sources for the purpose of accelerating the process of the bleaching gel and achieving better results.

- ↑ "UTCAT2638, Found CAT view, CRITICALLY APPRAISED TOPICs".

- ↑ Grace Sun, Lasers and Light Amplification in Dentistry. Dental Clinics of North America, Vol. 44 No. 4, October 2000.

- ↑ Bortolatto, J. F.; Pretel, H.; Floros, M. C.; Luizzi, A. C. C.; Dantas, A. a. R.; Fernandez, E.; Moncada, G.; Oliveira, O. B. de (2014-07-01). "Low Concentration H2O2/TiO_N in Office Bleaching A Randomized Clinical Trial". Journal of Dental Research. 93 (7 suppl): 66S–71S. doi:10.1177/0022034514537466. ISSN 0022-0345. PMC 4293723. PMID 24868014.

- ↑ "Statement on the Safety and Effectiveness of Tooth Whitening Products". American Dental Association. Retrieved 2010-07-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hasson, H; Ismail, AI; Neiva, G (18 October 2006). "Home-based chemically-induced whitening of teeth in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006202. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006202. PMID 17054282.

- ↑ Leonard, R. H.; Bentley, C.; Eagle, J. C.; Garland, G. E.; Knight, M. C.; Phillips, C. (2001). "Nightguard vital bleaching: a long-term study on efficacy, shade retention. side effects, and patients' perceptions". Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry: Official Publication of the American Academy of Esthetic Dentistry ... [et Al.] 13 (6): 357–369. ISSN 1496-4155. PMID 11778855.

- ↑ Carey, Clifton M. (June 2014). "Tooth Whitening: What We Now Know". The Journal of Evidence-based Dental Practice. 14 Suppl: 70–76. doi:10.1016/j.jebdp.2014.02.006. PMC 4058574. PMID 24929591.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Demarco, FF; Meireles, SS; Masotti, AS (2009). "Over-the-counter whitening agents: a concise review". Brazilian Oral Research. 23 Suppl 1: 64–70. doi:10.1590/s1806-83242009000500010. PMID 19838560.

- ↑ "UTCAT2368, Found CAT view, CRITICALLY APPRAISED TOPICs".

- 1 2 3 Carey, Clifton M. (June 2014). "Tooth Whitening: What We Now Know". The Journal of Evidence-based Dental Practice. 14 Suppl: 70–76. doi:10.1016/j.jebdp.2014.02.006. ISSN 1532-3382. PMC 4058574. PMID 24929591.

- ↑ "How to Whiten Your Teeth Naturally". Retrieved 2012-02-12.

- ↑ "Foods That Whiten Teeth Naturally". Retrieved 2012-02-12.

- ↑ Kwon, SR; Meharry, M.; Oyoyo, U.; Li, Y. (2015). "Efficacy of Do-It-Yourself Whitening as Compared to Conventional Tooth Whitening Modalities: An In Vitro Study". Operative Dentistry. 40 (1): E21–E27. doi:10.2341/13-333-LR. PMID 25279797.

- ↑ "Tooth Whitening Treatments". Retrieved 2010-07-05.

- ↑ Ricketts, David. Advanced Operative Dentistry, A Practical Approach. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier.

- ↑ Nathanson, D.; Parra, C. (July 1987). "Bleaching vital teeth: a review and clinical study". Compendium (Newtown, Pa.). 8 (7): 490–492, 494, 496–497. ISSN 0894-1009. PMID 3315205.

- ↑ Cohen, S. C. (May 1979). "Human pulpal response to bleaching procedures on vital teeth". Journal of Endodontics. 5 (5): 134–138. ISSN 0099-2399. PMID 296253.

- ↑ "Clinical Trial of Three 10% Carbamide Peroxide Bleaching Products". www.cda-adc.ca. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- 1 2 Leonard, R. H.; Haywood, V. B.; Phillips, C. (August 1997). "Risk factors for developing tooth sensitivity and gingival irritation associated with nightguard vital bleaching". Quintessence International (Berlin, Germany: 1985). 28 (8): 527–534. ISSN 0033-6572. PMID 9477880.

- ↑ Wang, Y; Gao, J; Jiang, T; Liang, S; Zhou, Y; Matis, BA (August 2015). "Evaluation of the efficacy of potassium nitrate and sodium fluoride as desensitising agents during tooth bleaching treatment-A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Dentistry. 43 (8): 913–23. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2015.03.015. PMID 25913140.

- ↑ Li, Y (1996). "Biological properties of peroxide-containing tooth whiteners". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 34 (9): 887–904. doi:10.1016/s0278-6915(96)00044-0. PMID 8972882.

- ↑ Kugel, G; Ferreira, S; Sharma, S; Barker, ML; Gerlach, RW (2009). "Clinical trial assessing light enhancement of in-office tooth whitening". Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry. 21 (5): 336–47. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8240.2009.00287.x. PMID 19796303.

- ↑ Kugel, G; Ferreira, S (2005). "The art and science of tooth whitening". Journal of the Massachusetts Dental Society. 53 (4): 34–7. PMID 15828604.

- ↑ Betke, H; Kahler, E; Reitz, A; Hartmann, G; Lennon, A; Attin, T (2006). "Influence of bleaching agents and desensitizing varnishes on the water content of dentin". Operative Dentistry. 31 (5): 536–42. doi:10.2341/05-89. PMID 17024940.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Freedman GA (15 December 2011). "Chapter 14: Bleaching". Contemporary Esthetic Dentistry. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-323-08823-7.

- ↑ Azer, SS; Machado, C; Sanchez, E; Rashid, R (2009). "Effect of home bleaching systems on enamel nanohardness and elastic modulus". Journal of Dentistry. 37 (3): 185–90. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2008.11.005. PMID 19108942.

- ↑ Haywood, Van & Houck, V.M. & Heymann, H.O.. (1991). Nightguard vital bleaching: Effects of various solutions on enamel surface texture and color. Quintessence Int. 22. 775-782.

- ↑ Lewinstein, I.; Hirschfeld, Z.; Stabholz, A.; Rotstein, I. (February 1994). "Effect of hydrogen peroxide and sodium perborate on the microhardness of human enamel and dentin". Journal of Endodontics. 20 (2): 61–63. doi:10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81181-7. ISSN 0099-2399. PMID 8006565.

- ↑ Rotstein I, Mor C, Arwaz JR (1997). "Changes in surface levels of mercury, silver, tin, and copper of dental amalgam treated with carbamide peroxide and hydrogen peroxide in vitro". Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 83:506–509.

- ↑ Hummert TW, Osborne JW, Norling BK, Cardenas HL (1993). "Mercury in solution following exposure of various amalgams to carbamide peroxides". Am J Dent 6:305–309.

- ↑ American Dental Association (November 2010) [September 2009]. "Tooth Whitening/Bleaching:Treatment Considerations for Dentists and Their Patients". ADA Council on Scientific Affairs.

- ↑ Swift EJ Jr, Perdigão J (1998). "Effects of bleaching on teeth and restorations". Compend Contin Educ Dent 19:815–820.

- 1 2 3 Dahl, J.E.; Pallesen, U. (2016-12-01). "Tooth Bleaching—a Critical Review of the Biological Aspects". Critical Reviews in Oral Biology & Medicine. 14 (4): 292–304. doi:10.1177/154411130301400406.

- ↑ WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION INTERNATIONAL AGENCY FOR RESEARCH ON CANCER (17 - 24 February 1998, 1999). "IARC MONOGRAPHS ON THE EVALUATION OF CARCINOGENIC RISKS TO HUMANS: Re-evaluation of Some Organic Chemicals, Hydrazine and Hydrogen Peroxide" (PDF). IARC. 71: 1597. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ SCCNFP (1999). Scientific Committee on Cosmetic Products and Non-Food Products intended for Consumers. Hydrogen peroxide and hydrogen peroxide releasing substances in oral health products. SCCNFP/0058/98. Summary on http://europa.eu.int/comm/food/fs/sc/sccp/out83_en.html and http://europa.eu.int/comm/food/fs/sc/sccp/out89_en.html(read 2002.31.10)

- ↑ "Teeth Whitening - Cost, Types, Results & Risks". DocShop. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ↑ "Tips for Keeping Teeth White". WebMD. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ↑ "Maintaining Your White Smile Article | Whitening Basics | Colgate® Oral Care Information Whitening & Bonding". www.colgate.com. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ↑ Krupp, Charla. (2008). How Not To Look Old. New York: Springboard Press, p.95.

- ↑ Antoniadou M, Koniaris A, Margaritis V, Kakaboura A. Tooth whitening efficacy of self-directed whitening agents vs 10% carbamide peroxide:a randomized clinical study. J Dent Oral Craniofac Res 2015;1(2):31-35 (doi 10.15761/DOCR.1000107).

- ↑ "Tooth Whitening". 8 Dec 2014.

- ↑ "Public Attitudes to Tooth Whitening Regulations" (PDF).